Introduction

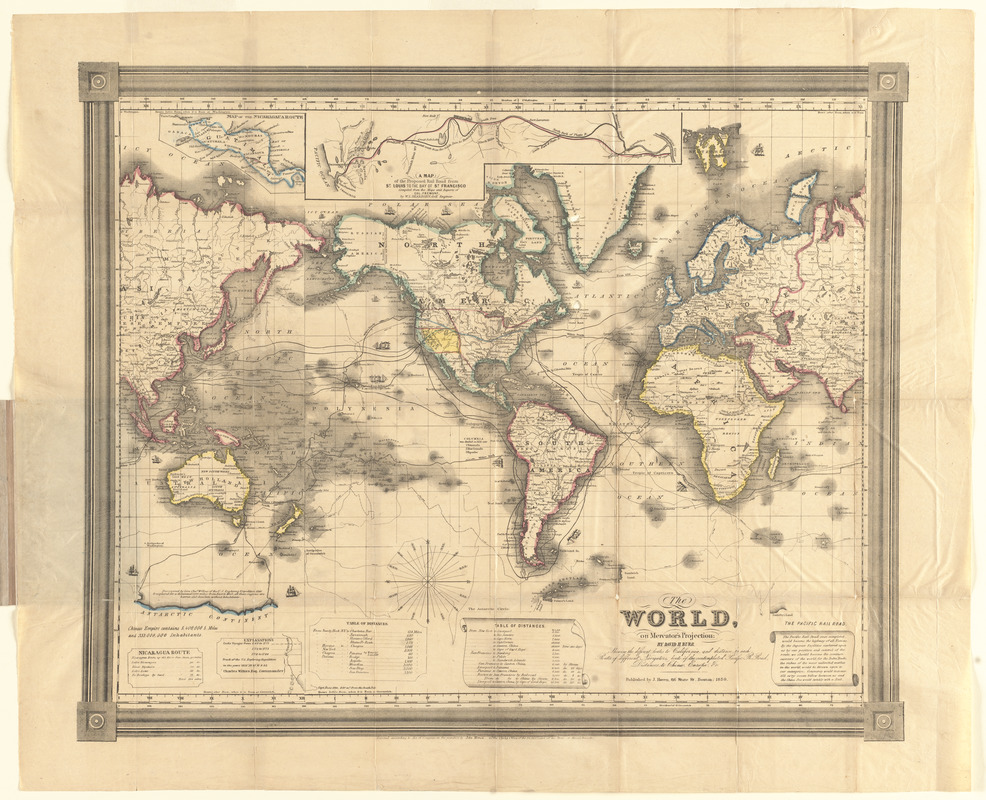

During the 19th century, the United States expanded dramatically westward. Immigrant settlers rapidly spread across the continent and transformed it, often through violent or deceptive means, from ancestral Native lands and borderlands teeming with diverse communities to landscapes that fueled the rise of industrialized cities. Historical maps, images and related objects tell the story of the sweeping changes made to the physical, cultural, and political landscape. Moving beyond the mythologized American frontier, this map exhibition explores the complexity of factors that shaped our country over the century.

The maps in this exhibition were created predominantly by Euro-American cartographers, and published by government agencies or commercial profit-seeking companies. They promote Euro-American culture and perpetuate certain interpretations of history. Considering the inherent power dynamics helps us understand that this was at the expense of other points of view – especially of indigenous peoples, those that were enslaved, and immigrant laborers, among many others. It is important to bear in mind how these documents reveal or conceal the ways people and communities were dispossessed, exploited, and annihilated. Unseen here but equally vital are stories of heroic resilience, resistance, and cultural preservation.

The Leventhal Map & Education Center stands on land that was once a water-based ecosystem that provided for the Massachusett people who lived in the Greater Boston area. We acknowledge these indigenous people, the devastating effects of settler colonialism on their communities, and their contemporary presence.

VIEWPOINT: The perspective of Native populations in the 19th century cannot be properly told in maps, because Native concepts about land are not two-dimensional, and qualifying ownership with a paper document was an imported European concept. During the rapid expansion of the United States, the idea of Native homeland, a multi-layered place giving life, sustenance, language, spiritual communion, and kinship, would change to a theory that land is preordained to be “improved” or “developed” for the purpose of commodification. This was a near universal change from Native land management systems that had sustained populations for millennia.

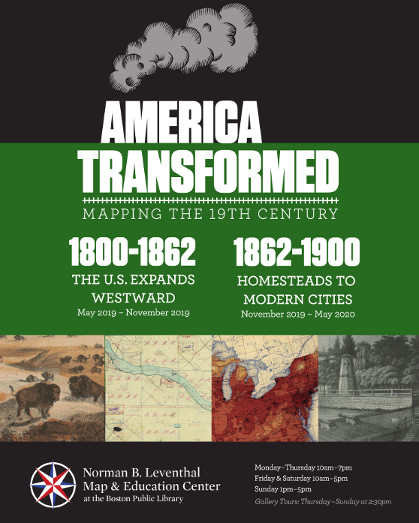

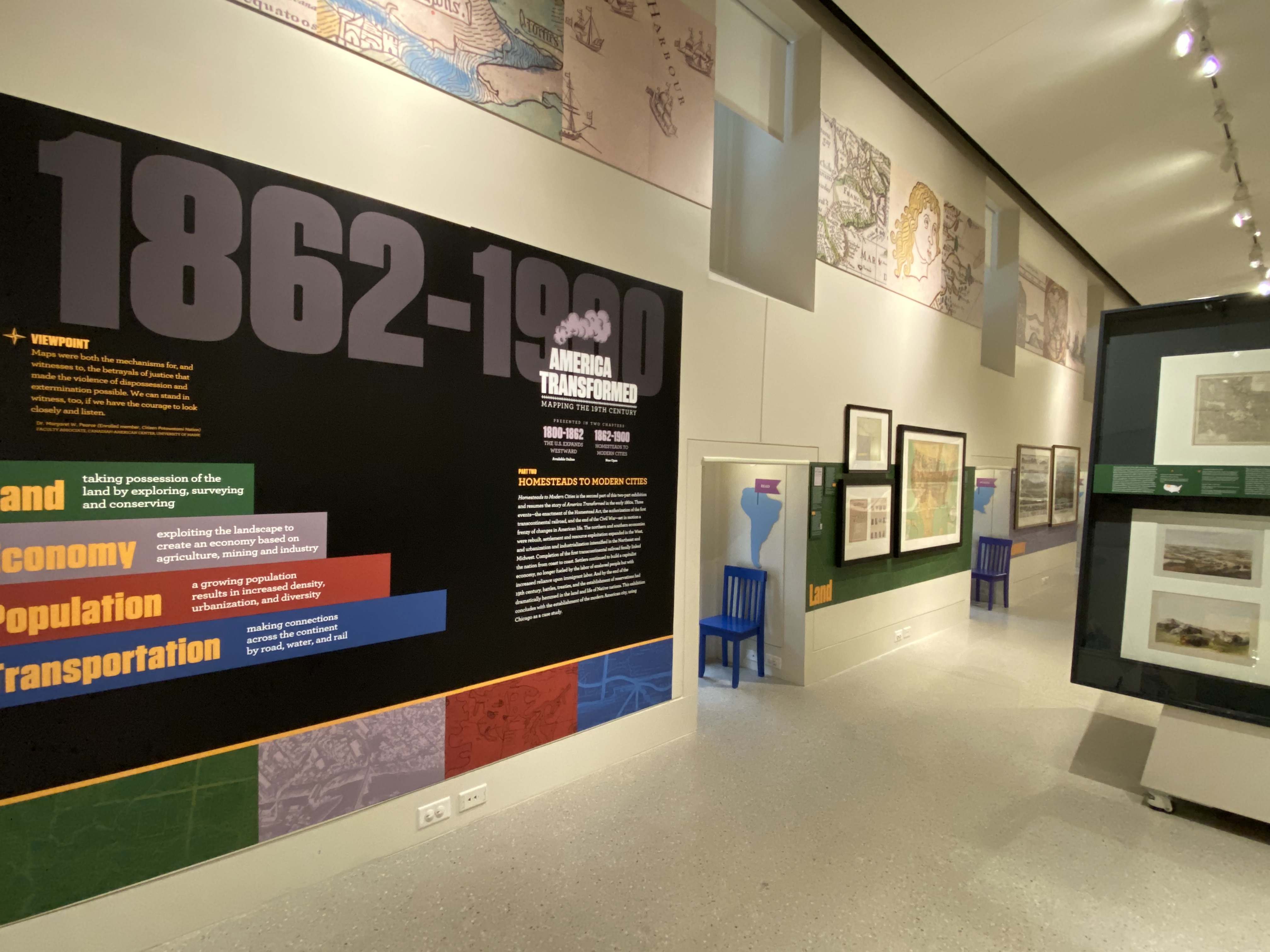

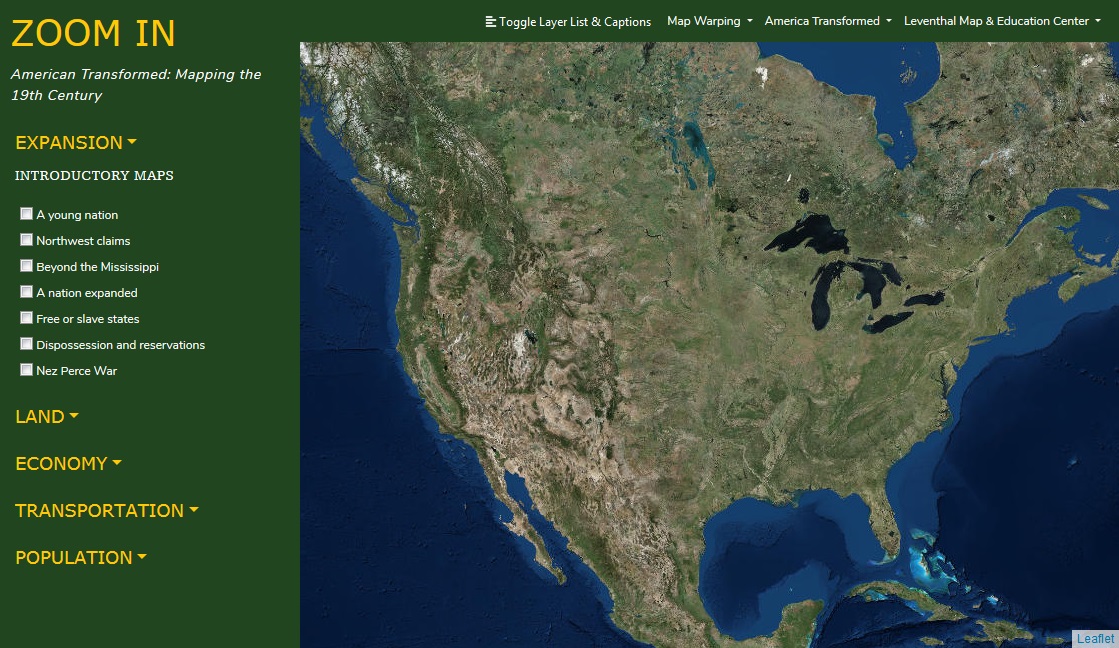

America Transformed: Mapping the 19th Century, is presented in two chapters:

Part One: The United States Expands Westward, 1800-1862

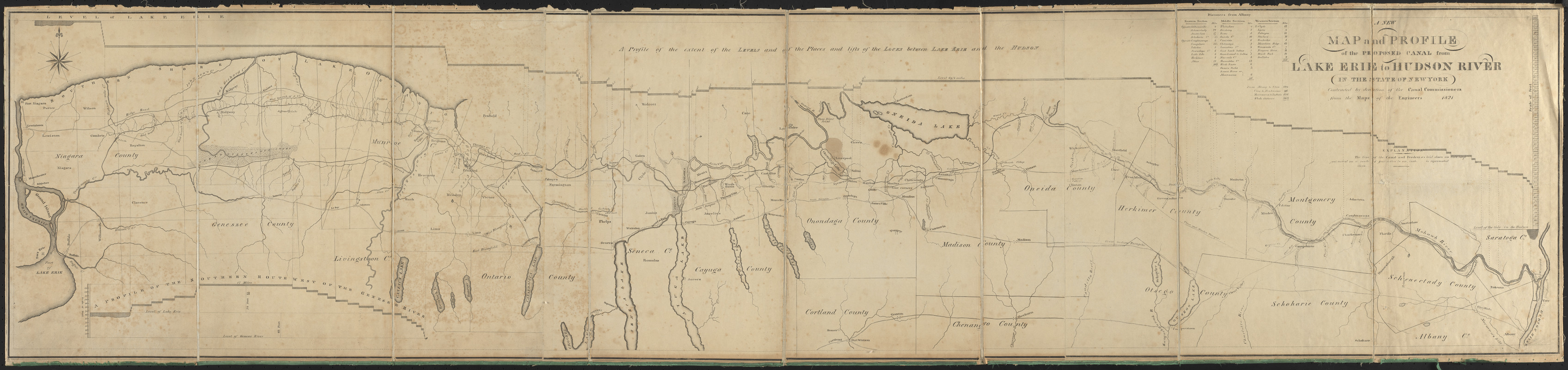

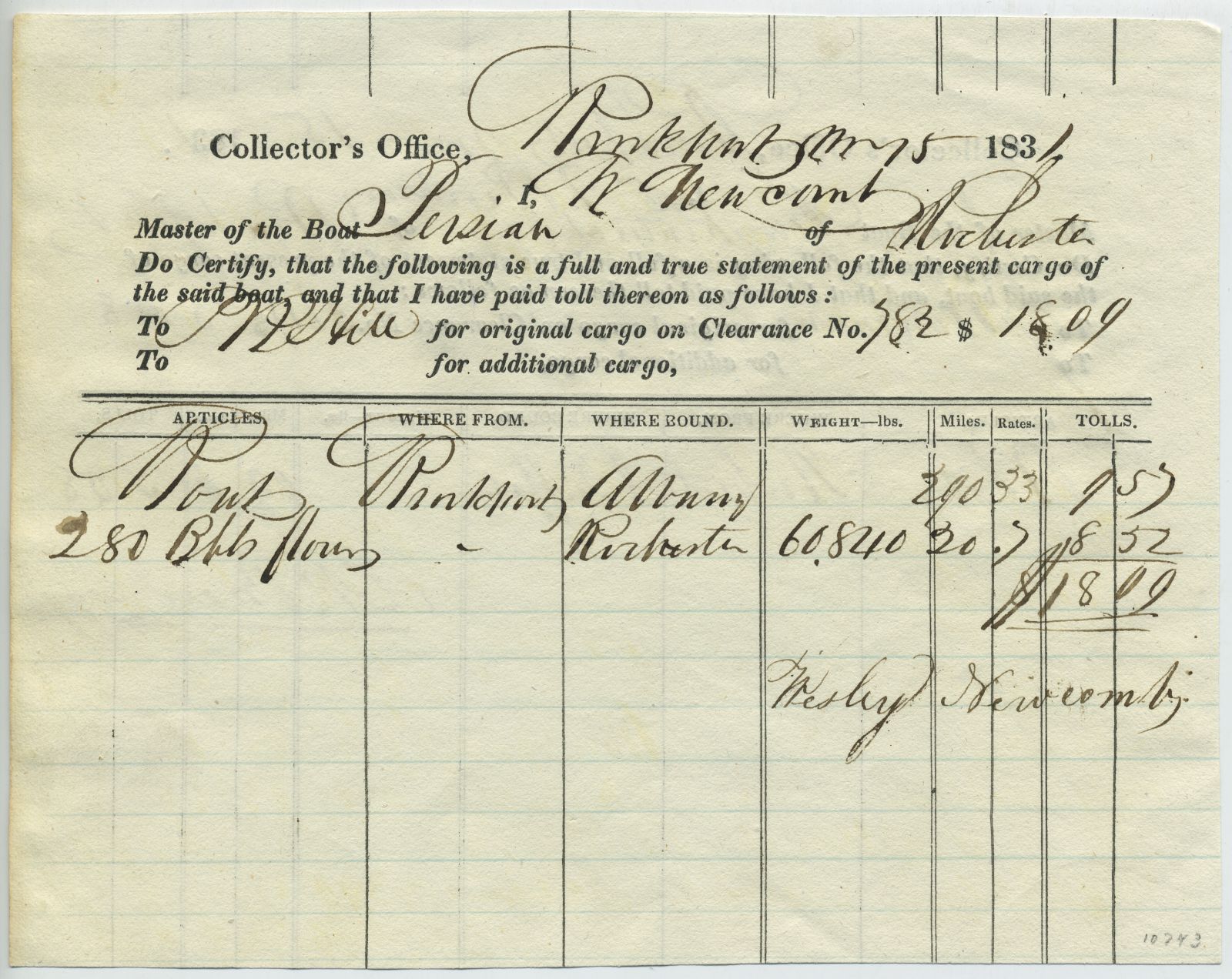

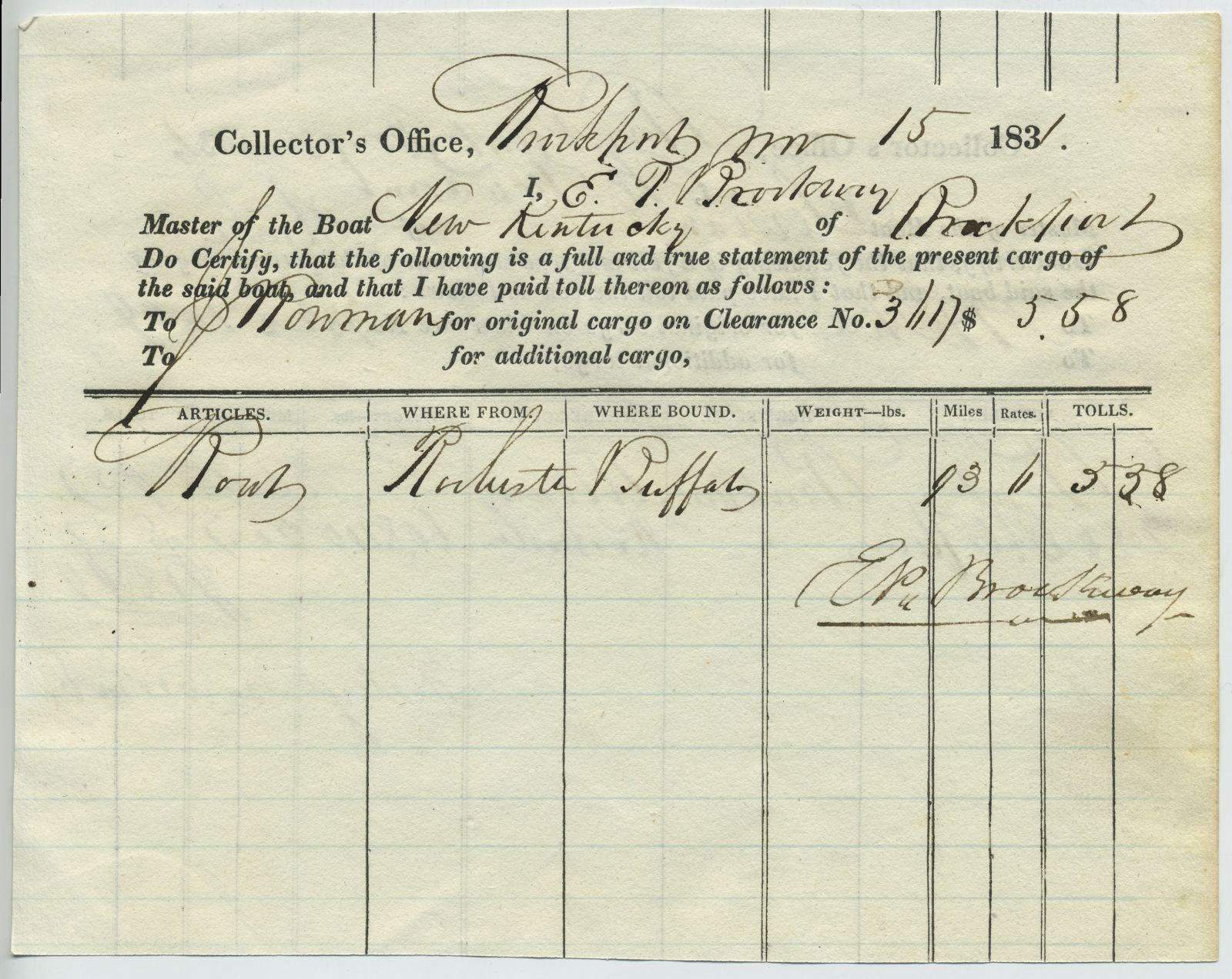

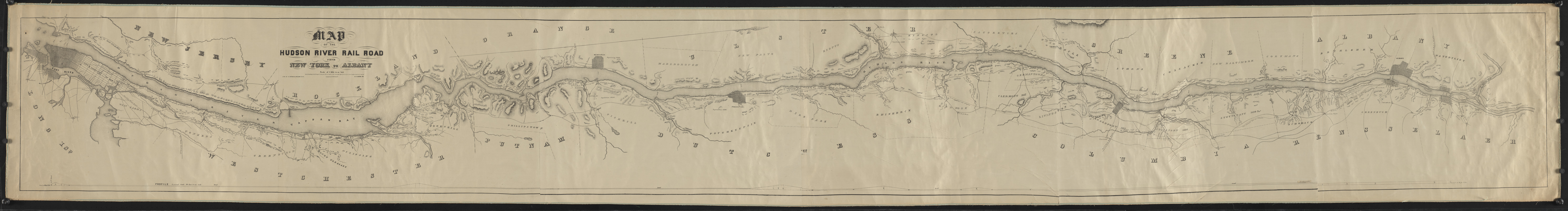

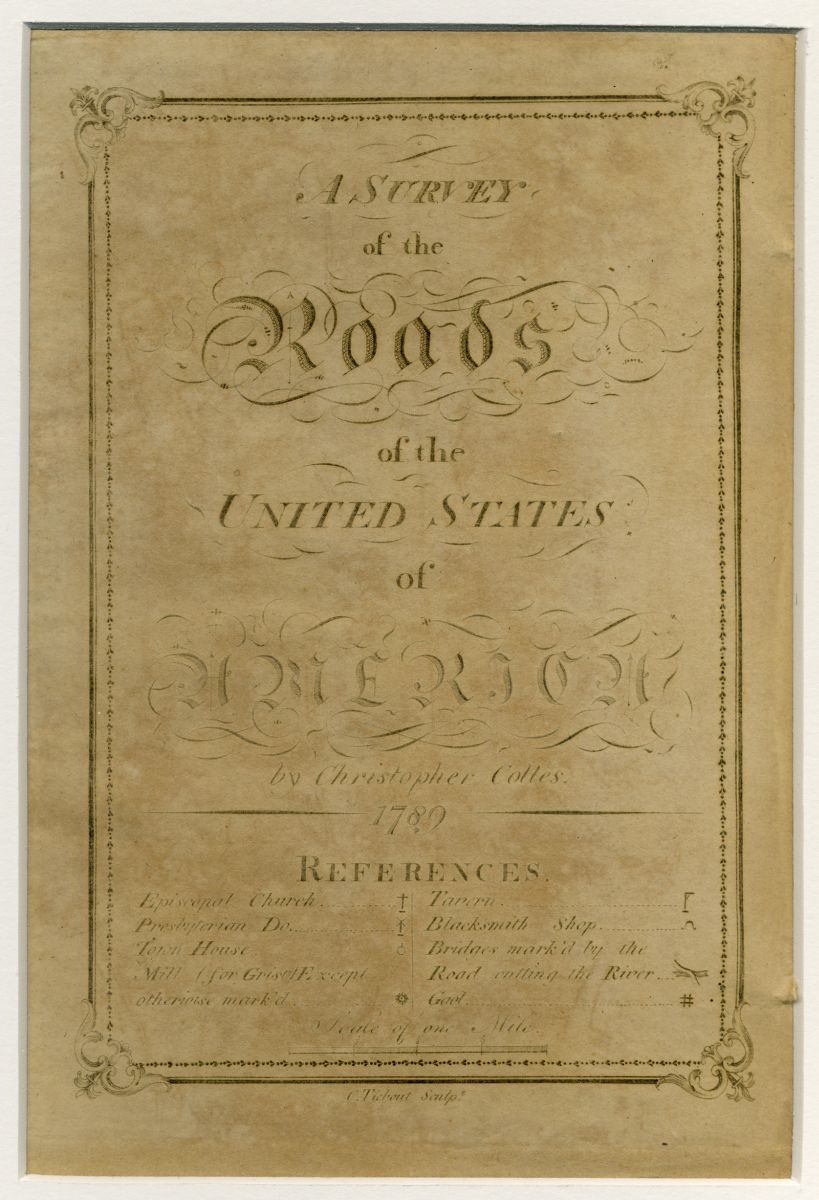

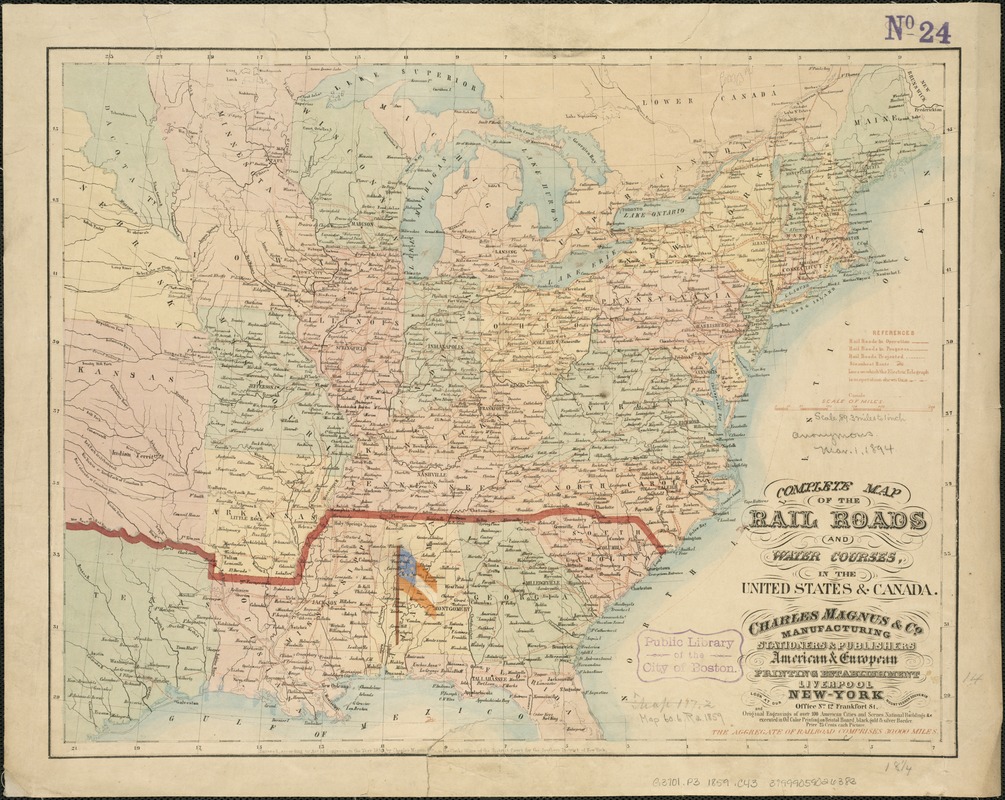

This exhibition begins at the end of the 18th century, when Euro-American settlers were exploring, surveying and rapidly taking over lands west of the Appalachians that were inhabited by Native peoples, as well as the French and Spanish. The newcomers developed canals, roads, and railroads, in many places appropriating Native trails, and created an integrated transportation network. Exploiting land and mineral resources, they initiated a capitalist economy based on agriculture, mining, and industry. This part of the story concludes with three significant events in the early 1860s that had major impact on the transformation of the nation’s physical and cultural landscape: the Civil War, the passing of the Homestead Act, and the authorization of the first transcontinental railroad.

VIEWPOINT: Maps were both the mechanisms for, and witnesses to, the betrayals of justice that made the violence of dispossession and extermination possible. We can stand in witness, too, if we have the courage to look closely and listen.

Part Two: Homesteads to Modern Cities, 1862-1900, November 2019-May 2020

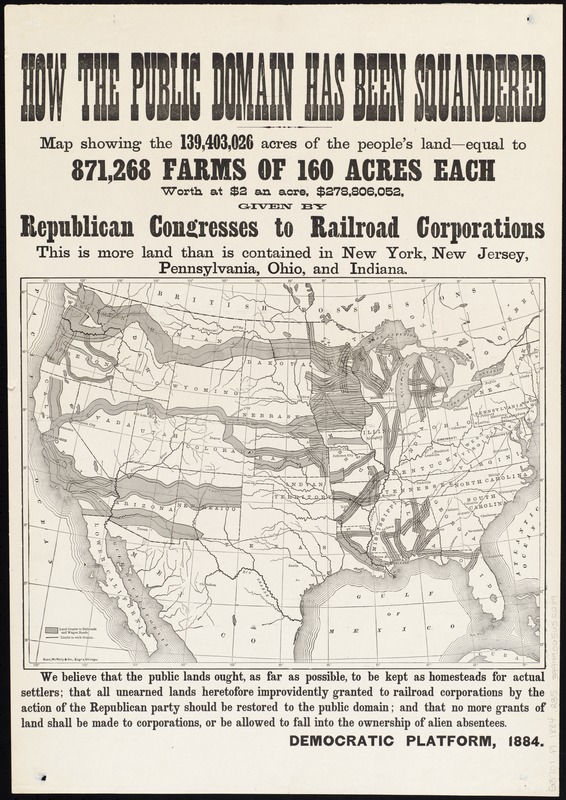

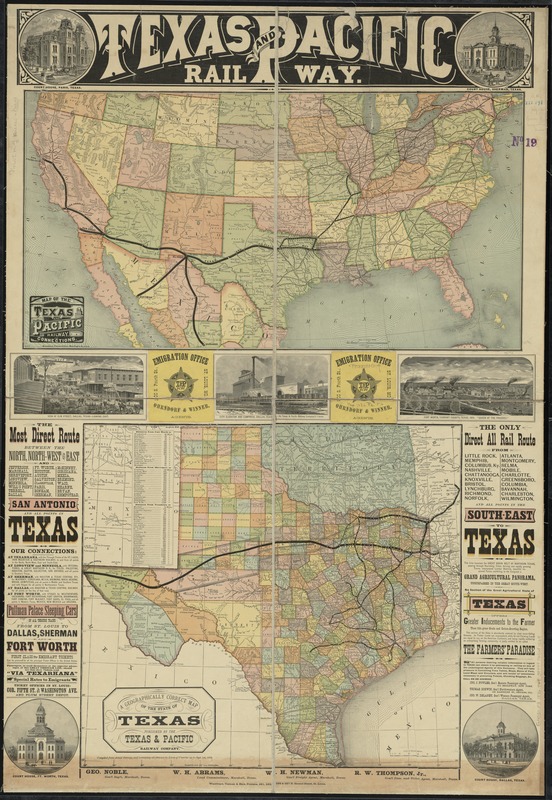

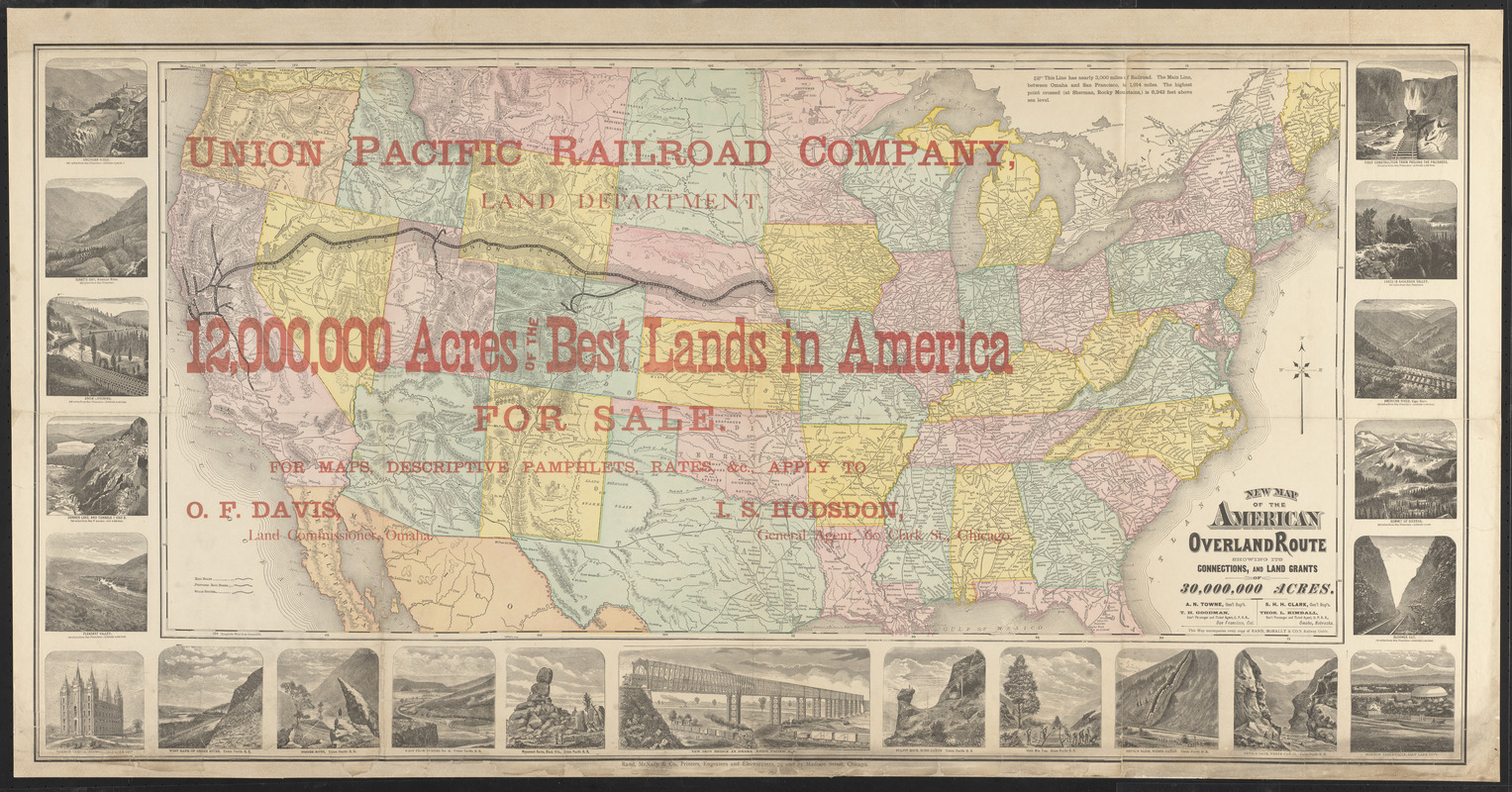

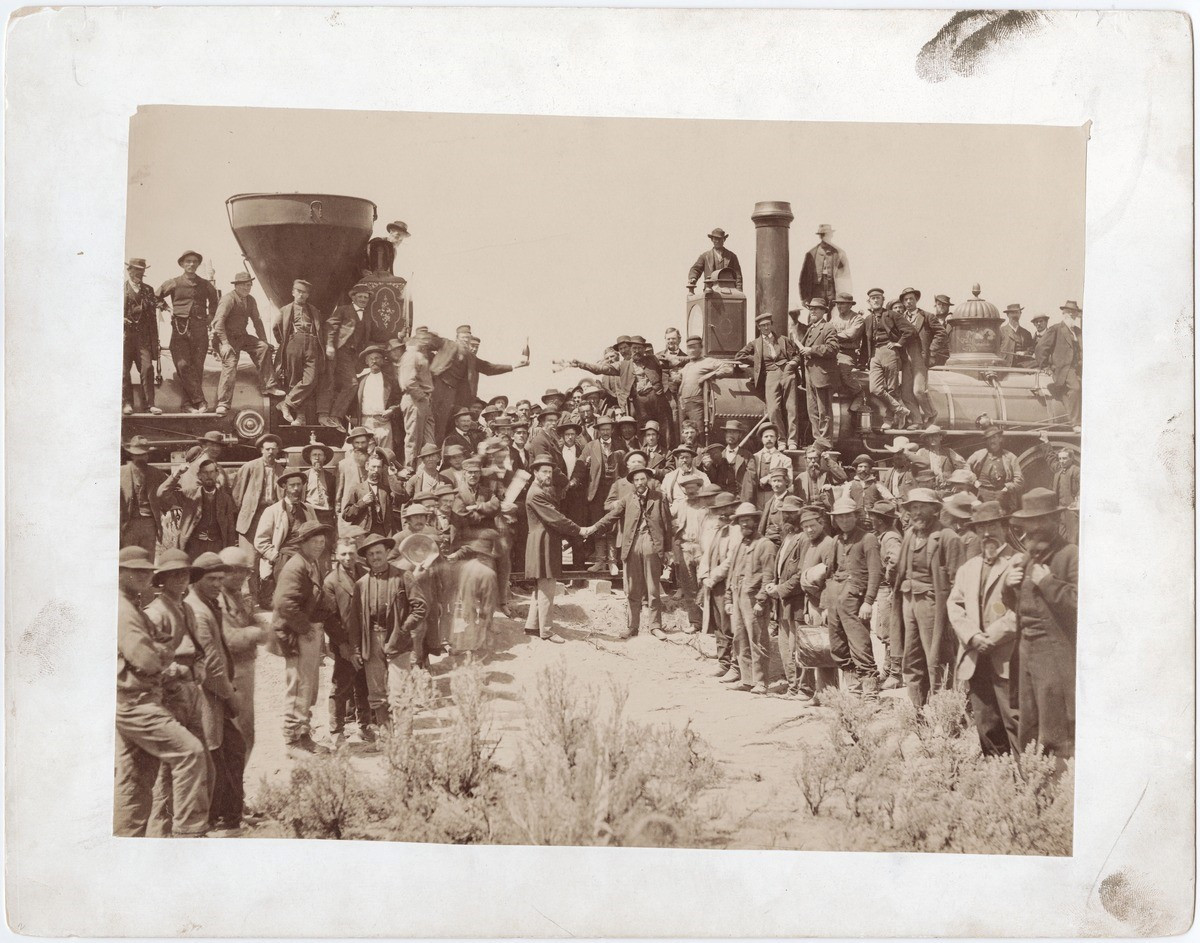

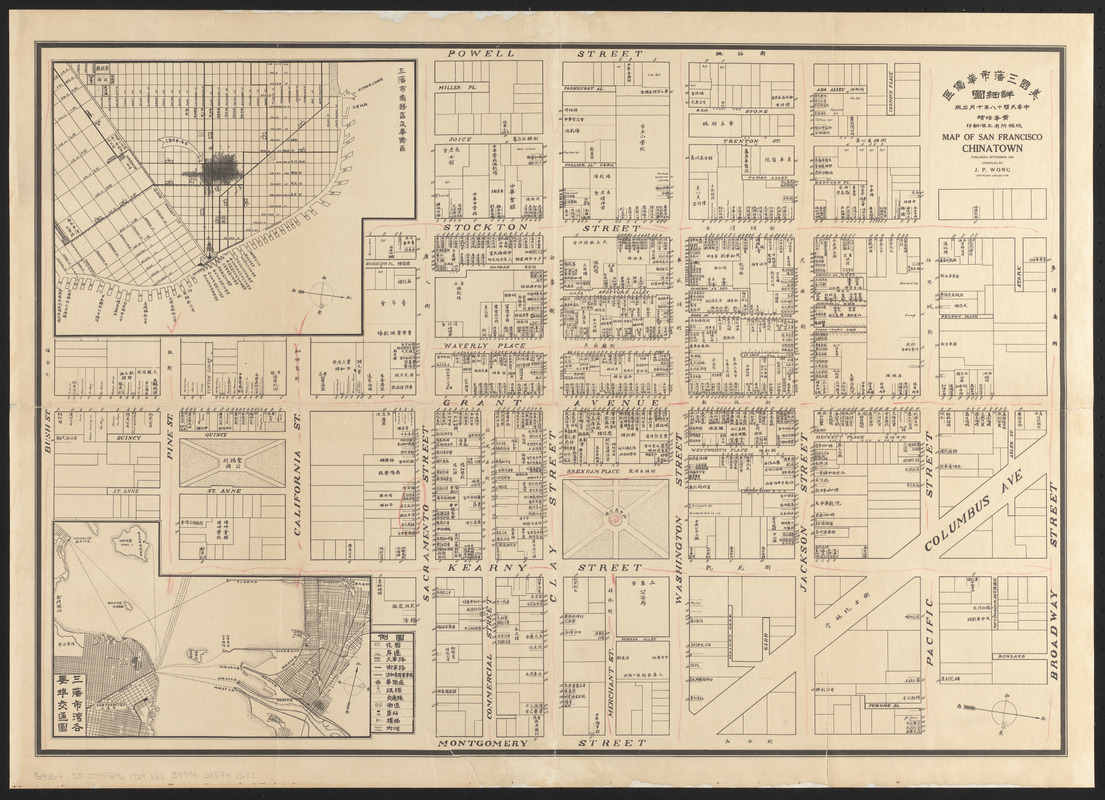

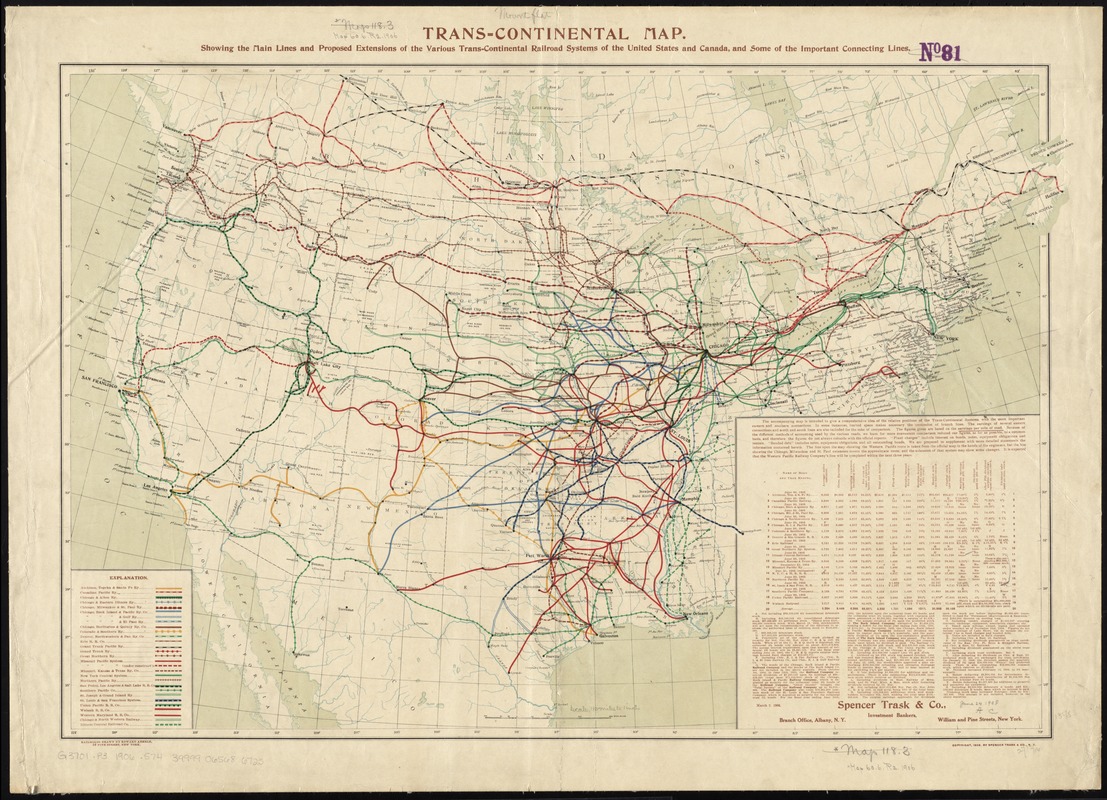

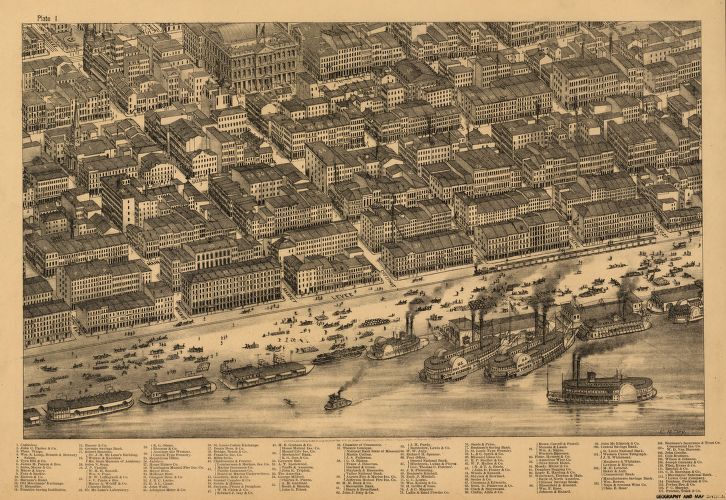

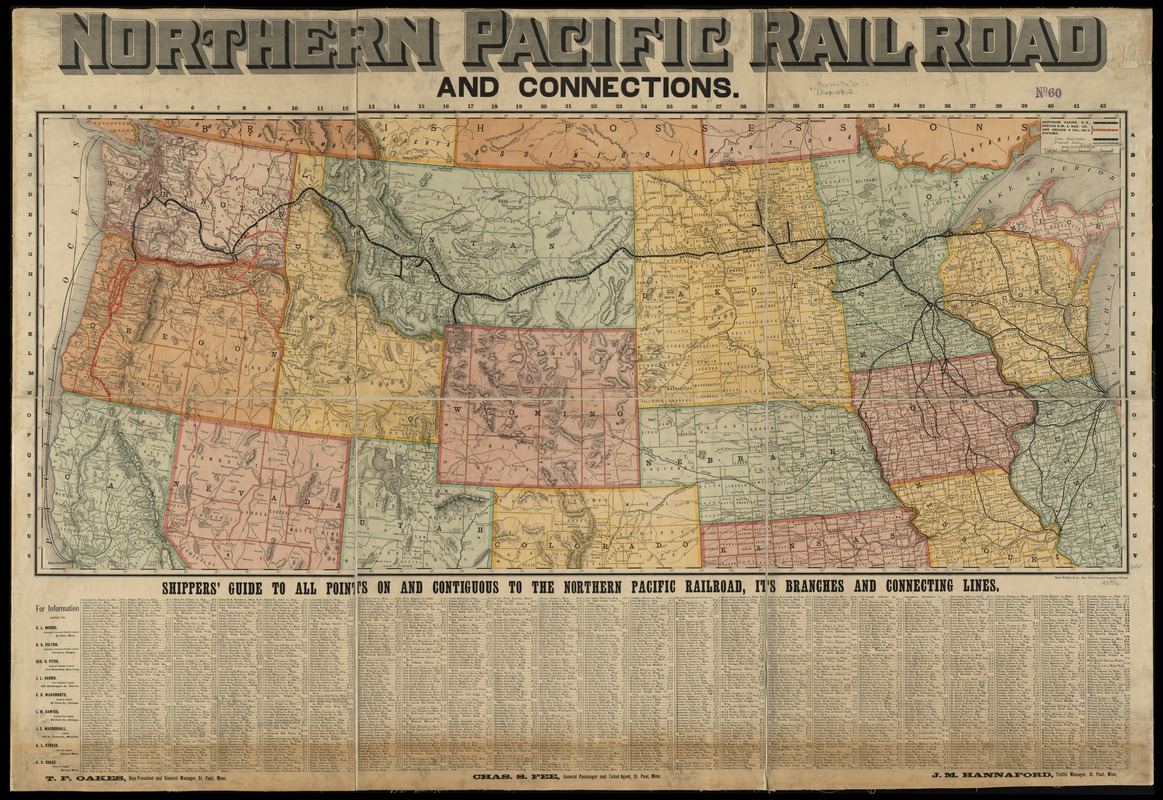

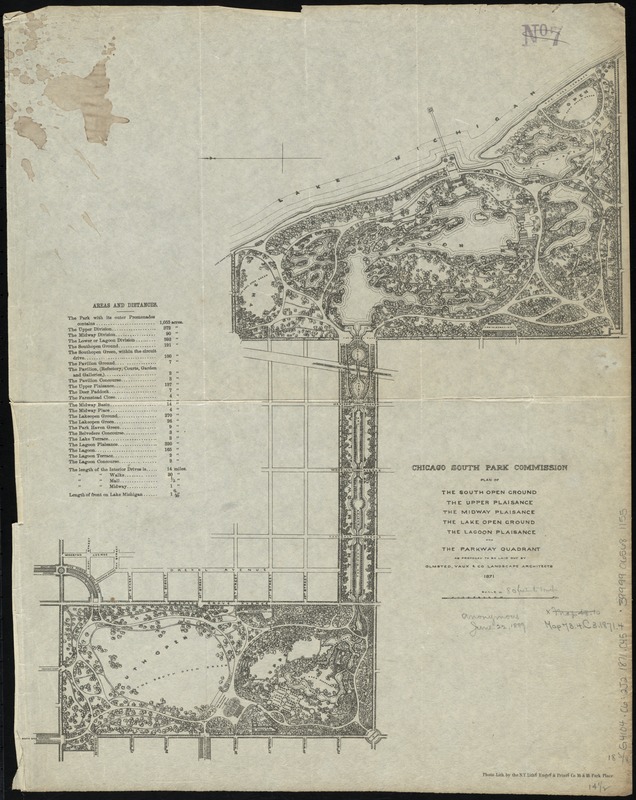

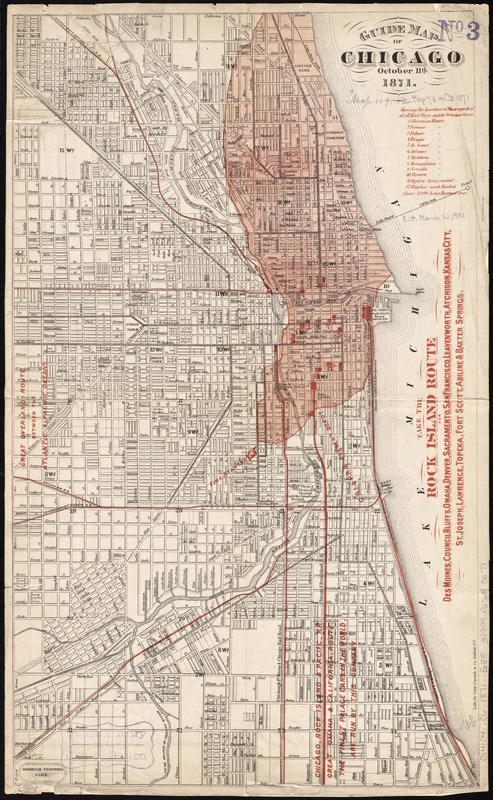

Homesteads to Modern Cities is the second part of this two-part exhibition and resumes the story of America Transformed in the early 1860s. Three events—the enactment of the Homestead Act, the authorization of the first transcontinental railroad, and the end of the Civil War—set in motion a frenzy of changes in American life. The northern and southern economies were rebuilt, settlement and resource exploitation expanded in the West, and urbanization and industrialization intensified in the Northeast and Midwest. Completion of the first transcontinental railroad finally linked the nation from coast to coast. Settlers continued to build a capitalist economy, no longer fueled by the labor of enslaved people but with increased reliance upon immigrant labor. And by the end of the nineteenth century, battles, treaties, and the establishment of reservations had dramatically hemmed in the land and life of Native nations. This exhibition concludes with the establishment of the modern American city, using Chicago as a case study.

The full-color, 212-page catalog of the two-part America Transformed exhibition is available for purchase in both hardcover and softcover editions. This richly illustrated book features reprints, details, and captions of the maps shown in the exhibition, along with seven essays exploring the various dimensions of America’s momentous nineteenth century. Purchase a catalog here.

Overview

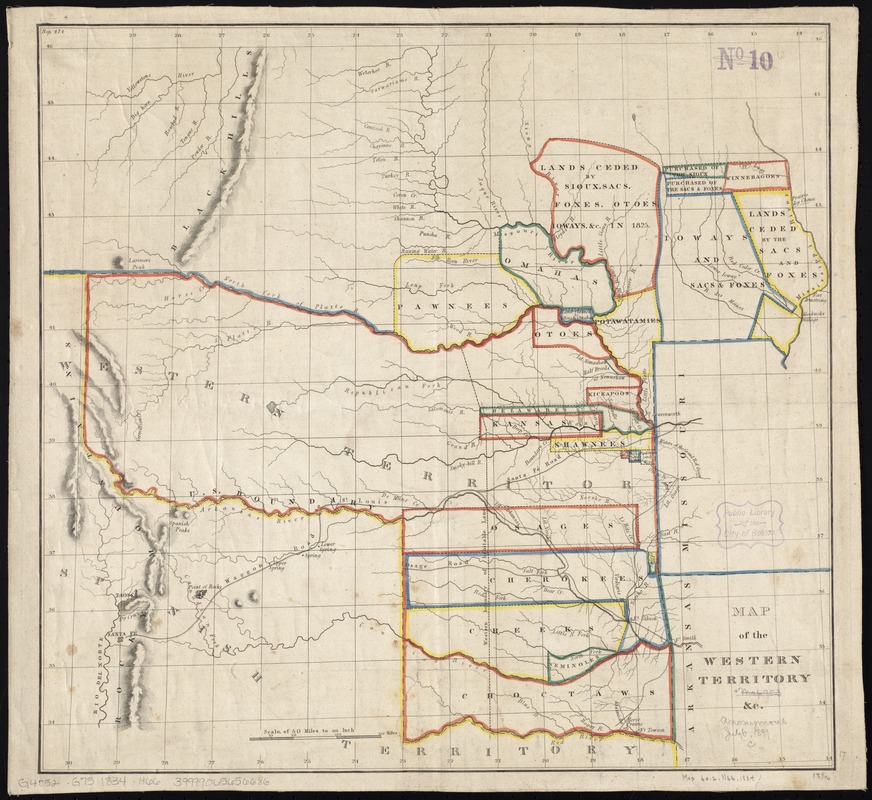

The maps in this introduction provide a chronological overview of how the boundaries of the United States changed during the 19th century. Originally comprised of 13 eastern states, the United States expanded to include 48 states and territories spanning the breadth of the continent. The familiar, tidy story of progress and inevitability of westward expansion is promoted in many historical American maps, including the growing demarcation of national, state, and county boundaries that etched U.S. colonial power and ideology into the landscape. Some of the maps presented here speak to encounters with Native people and offer insight into the complex and varied ways that Native and Euro-American people interacted, coexisted, and fought. Maps created by or copied from Native authors conceptualize mobility and relationships between people and places rather than precise measurements and boundaries. A bitter and uncomfortable undercurrent is the reality of the oppression and dispossession of millions of Native people.

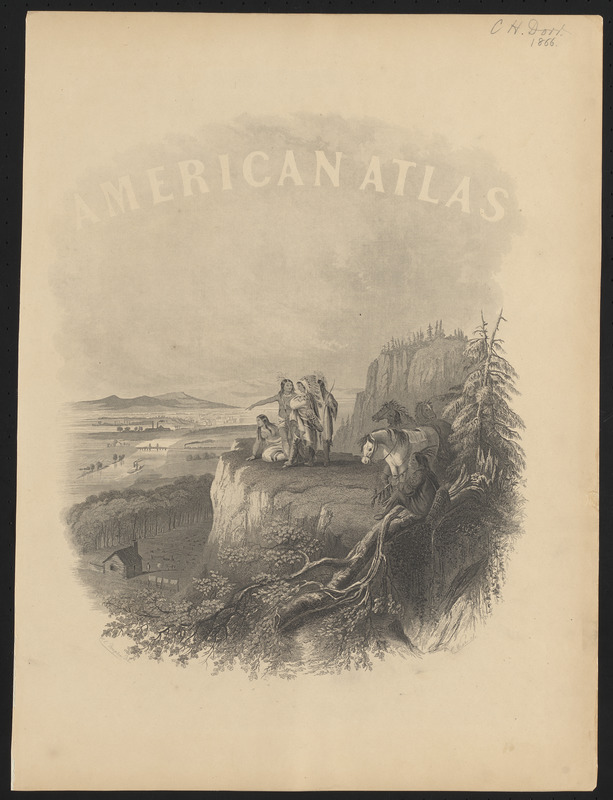

Alvin Jewett Johnson (1827-1884)

“American Atlas,” from "Johnson’s New Illustrated (Steel Plate) Family Atlas"

New York, 1866. Printed frontispiece, 18.5 x 14 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center. Reproduction 2019.

Published in 1866, this family atlas frontispiece promoted a popular, mythic vision of the American West. Four Native people point to features of white advancement: a homestead stands in an area cleared of trees, a steamship huffs toward a railroad bridge, and smoke rises from a distant factory. Bucolic depictions like these implied indigenous people docilely accepted their displacement. They also portrayed Native people as dwelling in an untouched, natural environment, despite the reality that they, too, impacted the land. The image promoted the idea that white settlers tamed the wilderness and advanced their civilization where it was “missing.”

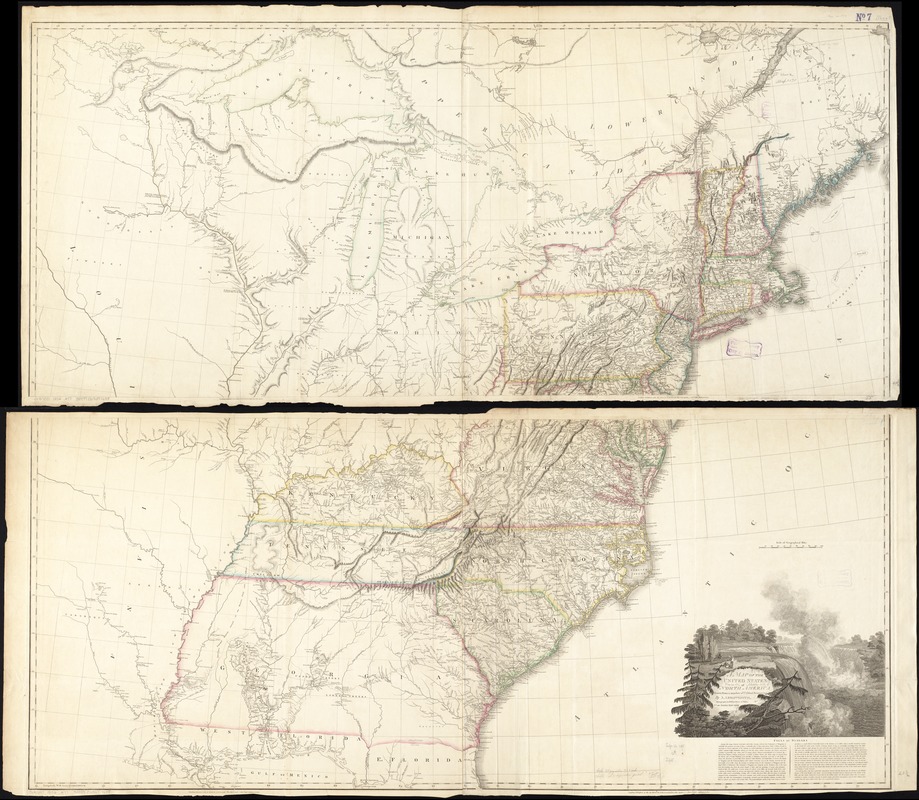

Aaron Arrowsmith (1750-1823)

"A Map of the United States of North America"

London, 1802. Printed map, 48 x 55.5 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center. Reproduction 2019.

This large wall map details the United States at the onset of the 19th century. The young nation’s western boundary is the Mississippi River, based on the 1783 Paris Peace Treaty. In addition to the original 13 states, three new ones appear: Vermont, Kentucky, and Tennessee. As Euro-American settlers moved across the Appalachian Mountains, they encountered Native and French communities, including the Tsalagi (Cherokee), Chikasha (Chickasaw), Chahta (Choctaw), and Mvskoke (Creek) who inhabited expansive ancestral lands in the southern portion of this trans-Appalachian region. An image of Niagara Falls, which became part of the nation’s popular iconography, adorns the cartouche.

Nicholas King (1771-1812), after Meriwether Lewis and William Clark

"Map of Part of the Continent of North America . . . from the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean . . ."

Washington, D.C., 1806? Manuscript map, 26.5 x 38 inches. Courtesy of the Boston Athenaeum. Reproduction 2019.

Following the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France in 1803, President Thomas Jefferson commissioned the Corps of Discovery to explore and map the new territory, develop trade and diplomatic relations with tribal nations, and establish a claim to the Pacific Northwest. Commanded by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, the Corps kept a daily record of geographic observations and prepared numerous manuscript maps incorporating information provided by Native people. Particularly noteworthy are the names of tribal communities, annotated in red ink. This was the federal government’s first attempt to accurately map the presence of Native peoples (and number of warriors) west of the Mississippi River. These lands were claimed by the United States but firmly controlled by Native peoples.

James Hamilton Young

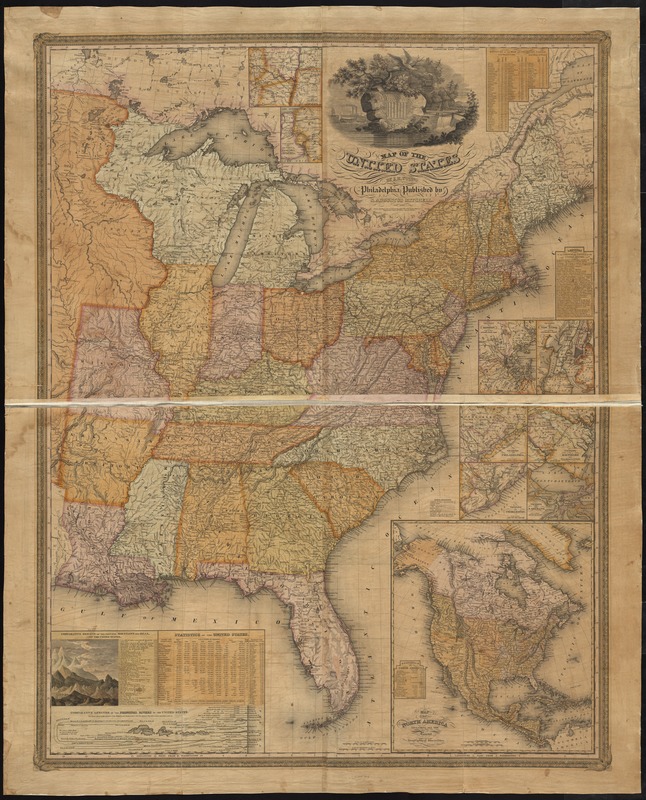

"Map of the United States"

Philadelphia, 1831. Printed map, 42.5 x 33.5 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center. Reproduction 2019.

By 1831, the land east of the Mississippi had been divided into 24 states and the Michigan territory. In addition, American settlement and Native dispossession started to expand west of the Mississippi with the addition of Louisiana, Arkansas, and Missouri. The mapmakers also labeled the lands occupied by the Tsalagi (Cherokee), Mvskoke (Creek), Chikasha (Chickasaw), and Chahta (Choctaw) in large capital letters, although just a year earlier, the federal government had enacted the Indian Removal Act, which forced many tribes from their ancestral homelands. The law paved the way for the Trail of Tears, the name given to a series of forced relocations of these Native nations.

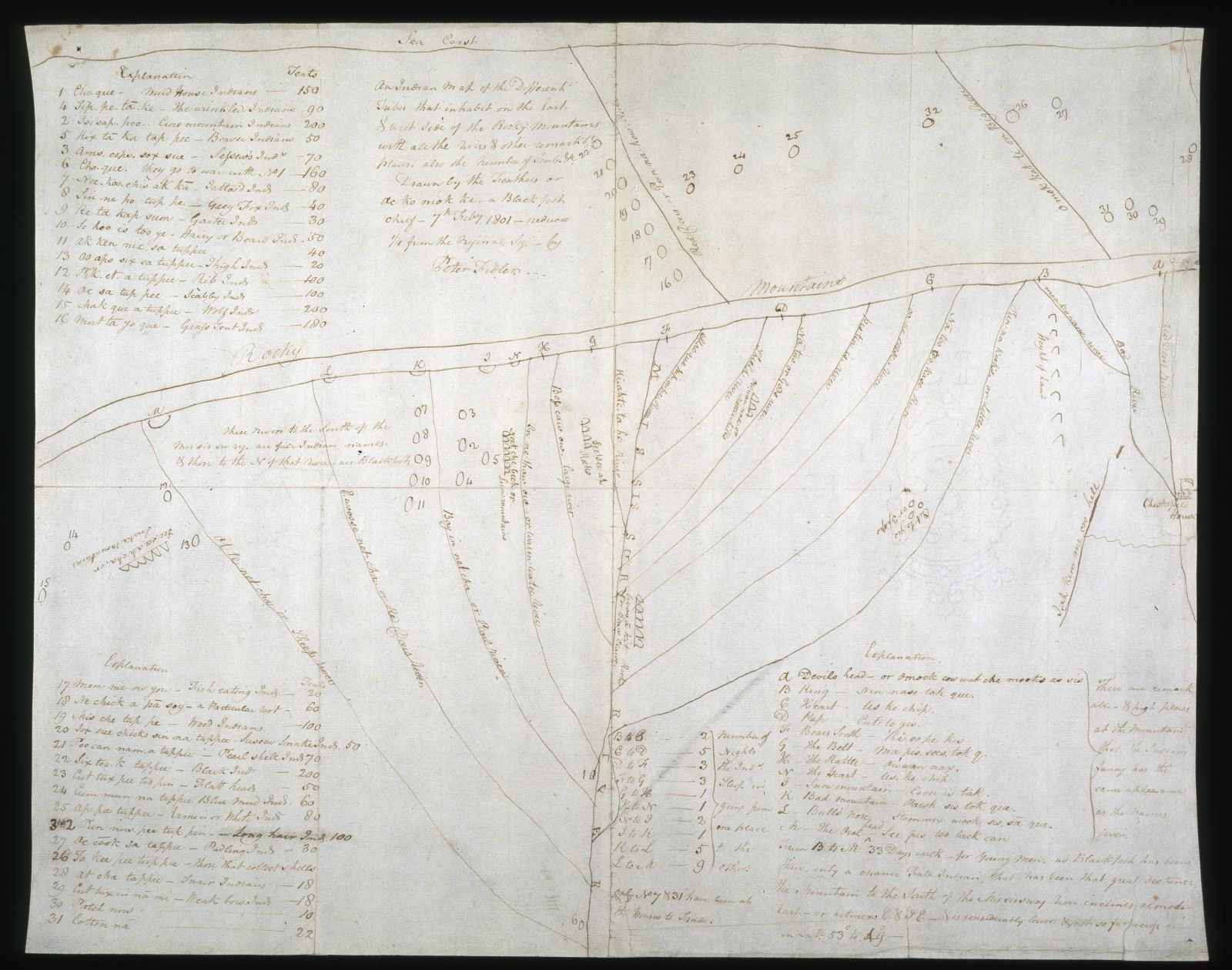

Peter Fidler (1769-1822) after Ac ko mok ki

"An Indian Map of the Different Tribes, that Inhabit the East and West Side of the Rocky Mountains . . ."

1801. Manuscript map, 15 x 19 inches. Courtesy of Hudson's Bay Company Archives, Provincial Archives of Manitoba, G.1/25. Reproduction 2019.

Peter Fidler, cartographer and fur trader, recorded this map in 1801 based on one provided by Ac ko mok ki, a Blackfoot chief. West is at the top, and a double line represents the Rocky Mountains. Below, the headwaters of the Missouri and Saskatchewan River systems flow eastward down the map. Over 30 tribal nations in the upper Great Plains region are noted. When the map was forwarded to London, the physical geography was integrated into a printed map but the data pertaining to the tribal nations was omitted to suggest that this region was uninhabited.

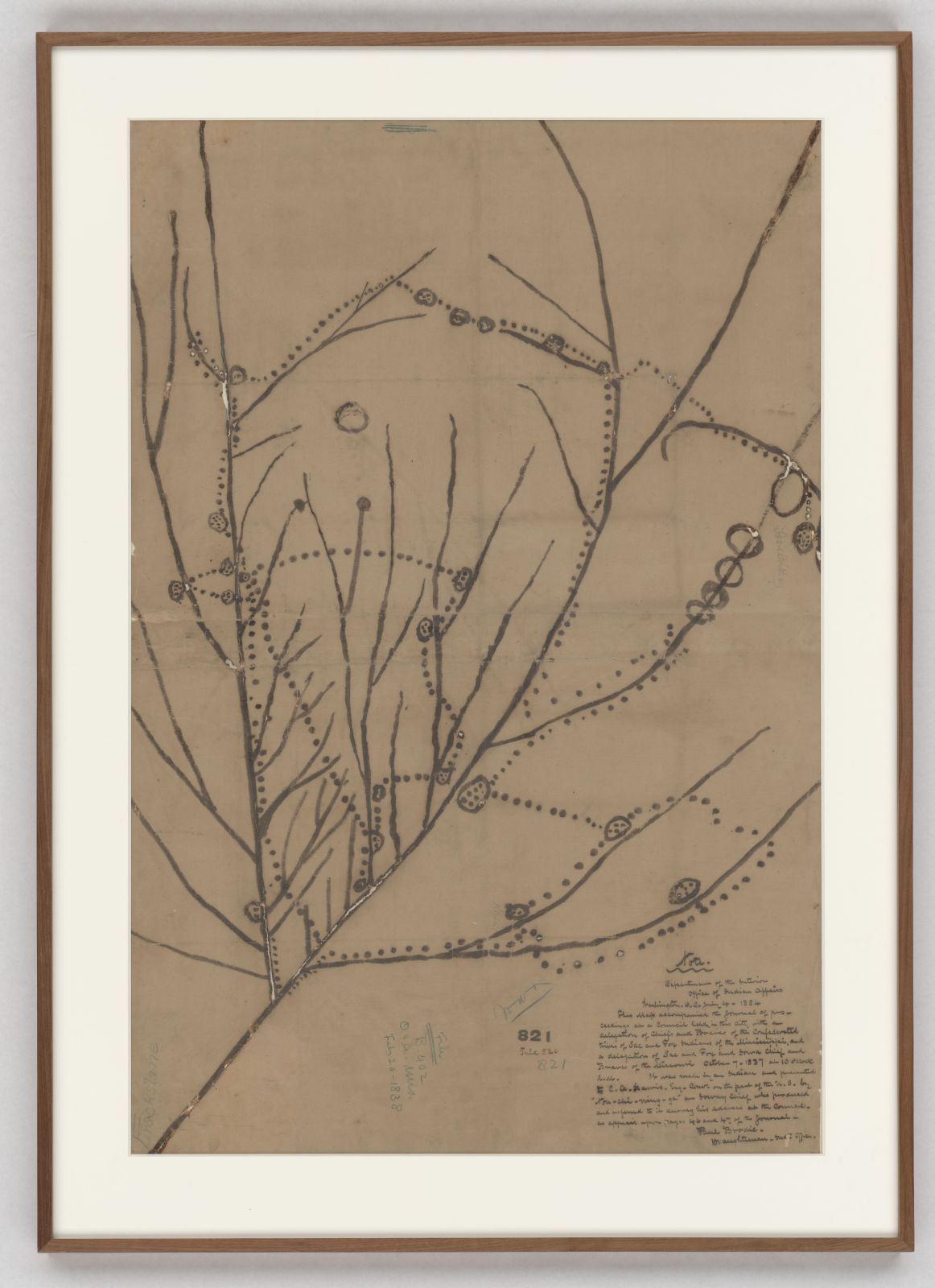

"Non-Chi-Ning-Ga’s Map of the Migration of his Indian Ancestors"

1837. Manuscript map, 41 x 27.5 inches. Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 75, map 821. Reproduction 2019.

An Ioway chief named Non-Chi-Ning-Ga (“No Heart of Fear”) prepared this schematic diagram of the Upper Mississippi and Missouri River drainages for an 1837 treaty council in Washington, DC. In an effort to prove the lands were theirs, rather than Sac and Fox, the map records Ioway place names and ancestral village sites. The tribe’s migration routes for two centuries are marked in dotted lines, from Green Bay on Lake Michigan (on the right) through Wisconsin to the Mississippi River (central diagonal line) to the Missouri (vertical line on left). Although the Sac and Fox did not dispute the history expressed in this map, the U.S. government forced the Ioway to relocate to reservations.

Joseph Hutchins Colton (1800-1893)

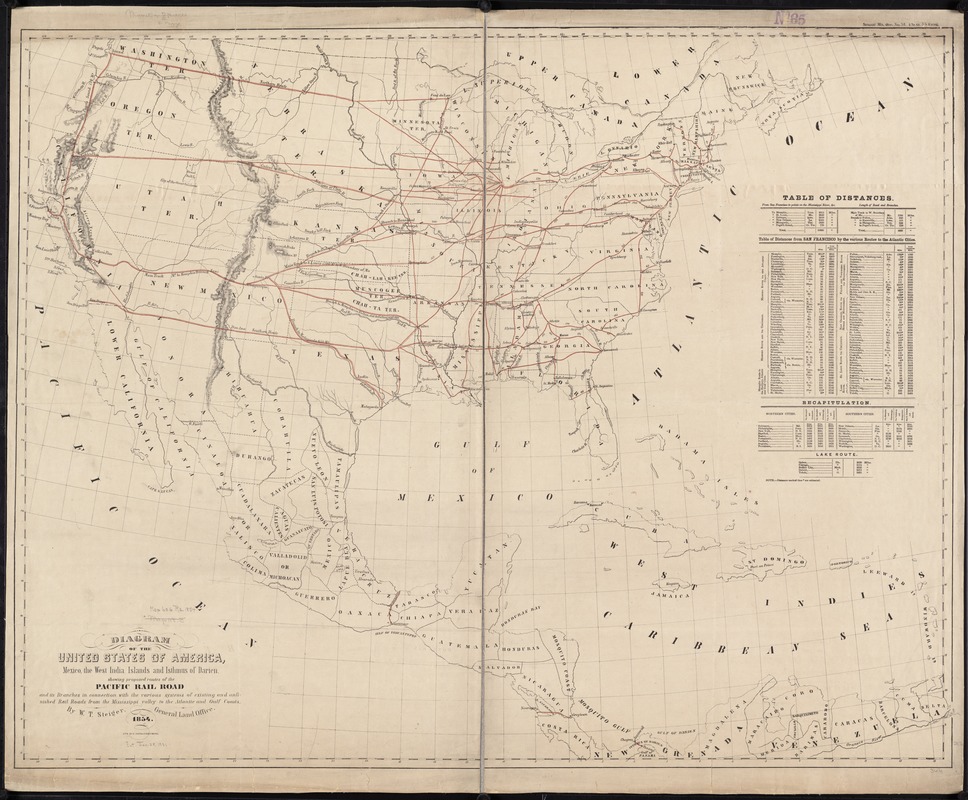

"Colton's Map of the United States of America … from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean"

New York, 1854. Printed map, 47 x 55 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center. Reproduction 2019.

During the 1840s and early 1850s, the political geography of the West changed dramatically. The nation annexed Texas, established the 49th parallel as its northwestern boundary, claimed the Oregon Territory, and won land from Mexico following the Mexican-American War. By the time this map was published in 1854, the United States included 31 states and seven territories. Commercially published maps like this one celebrated the nation’s expansion with small vignettes dispersed throughout these newly acquired territories depicting Native people, wildlife, and a wagon train. It also suggests a unified nation, but a statistical table enumerating free and enslaved population alludes to conflicts over whether to extend slavery into the western territories and foreshadows the impending Civil War.

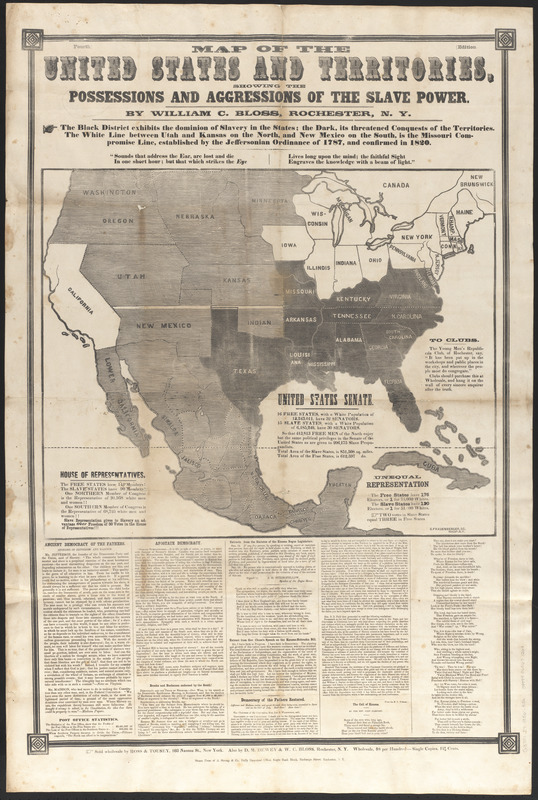

William C. Bloss (1795-1863)

"Map of the United States and Territories Showing the Possessions and Aggressions of the Slave Power"

New York and Rochester, NY, 1856? Printed broadside, 41.5 x 27.5 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center. Reproduction 2019.

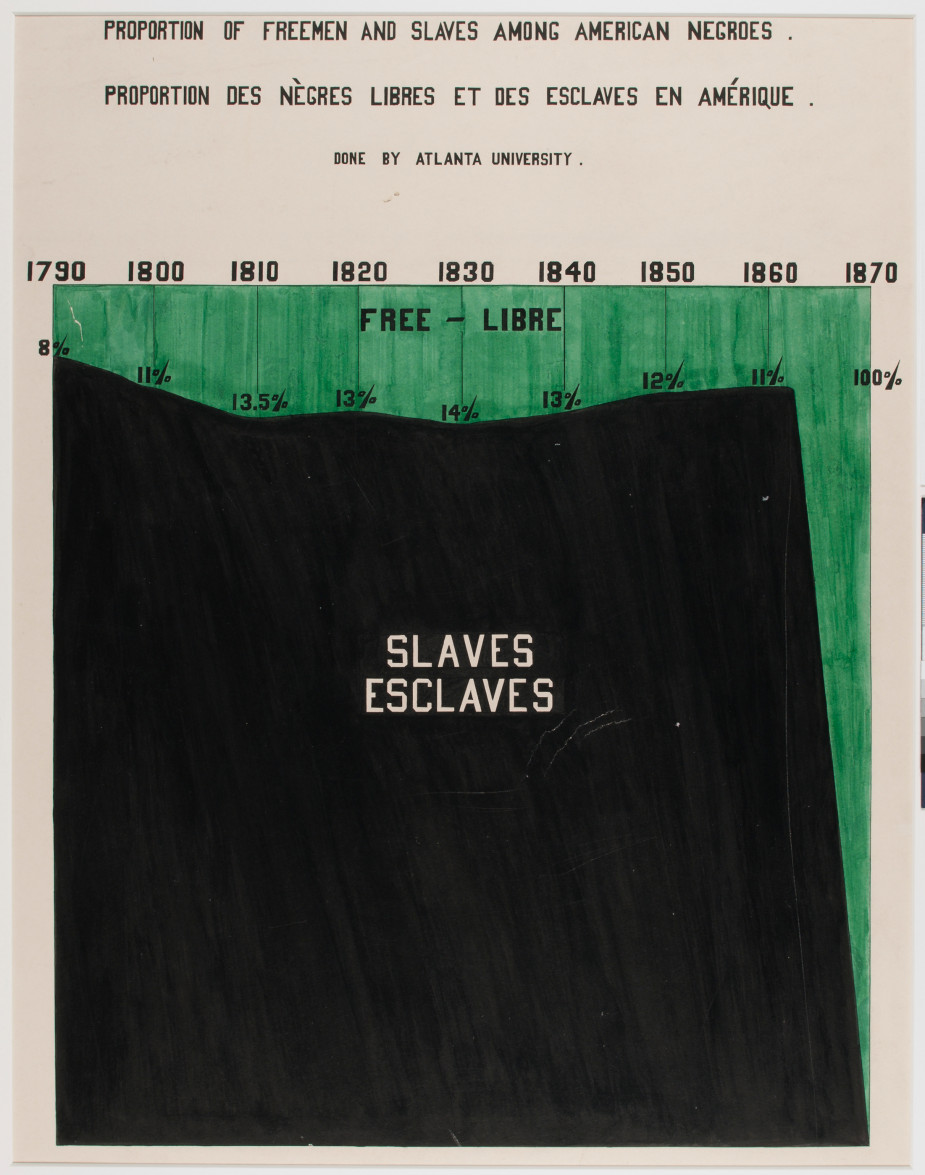

While Colton’s map suggests a unified nation extending from the Atlantic to the Pacific, this broadside published about the same time boldly addresses the slavery issue. It identifies free states in white, slave states in black, and contested territories in gray. Issued during the 1856 presidential election, this stark graphic implicitly supports the candidacy of Republican John C. Frémont, who opposed slavery’s expansion. It also forcefully challenges the so-called Three-Fifths Compromise which counted three out of five slaves toward calculating southern political representation, while denying those enslaved peoples any voting privileges or freedom.

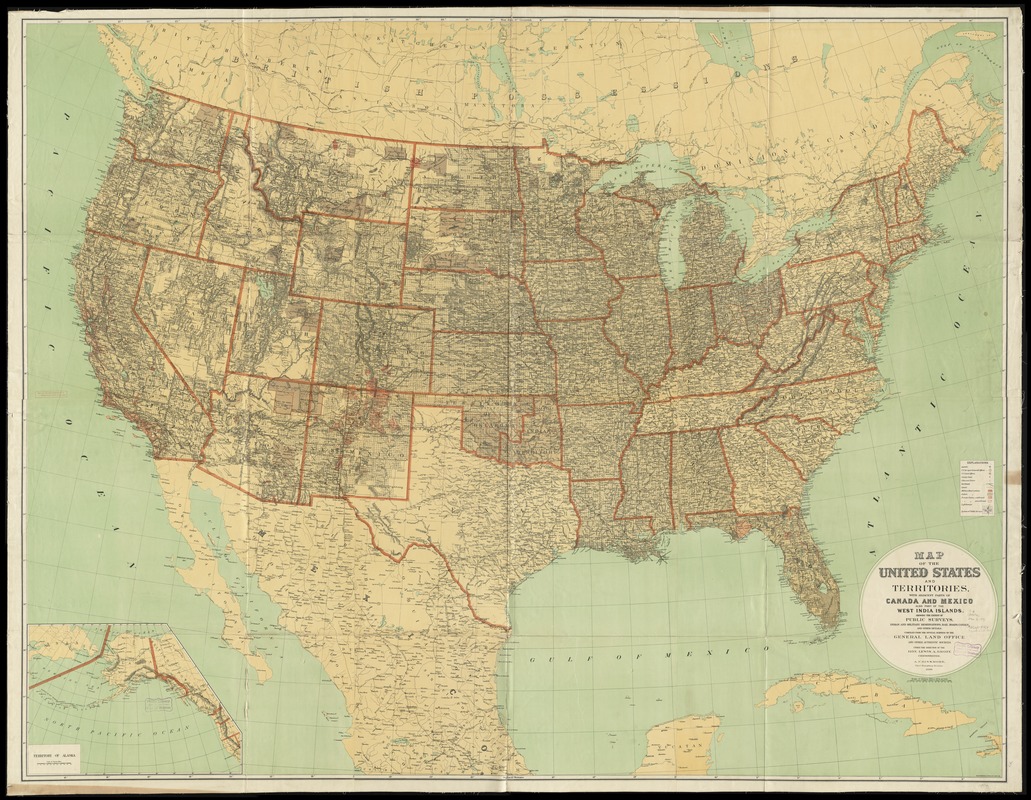

U.S. General Land Office

"Map of the United States and Territories, Showing the Extent of Public Surveys. . ."

Washington, DC, 1871. Printed map, 27.5 x 55 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center. Reproduction 2019.

Published shortly after the American Civil War, this map depicts a reunited nation, but it also provides an inventory of land and mineral resources. While the General Land Office, the federal agency responsible for surveying and selling public lands, produced this map as a yearly update of its activities, it also promoted further expansion of western settlement. The square grid pattern appearing in most states west of the Appalachian Mountains indicates the extent of public land or township surveys. Color coding identifies the location of mineral resources. Reflecting the efforts to unify the nation after the Civil War, this map marks the route of the first transcontinental railroad.

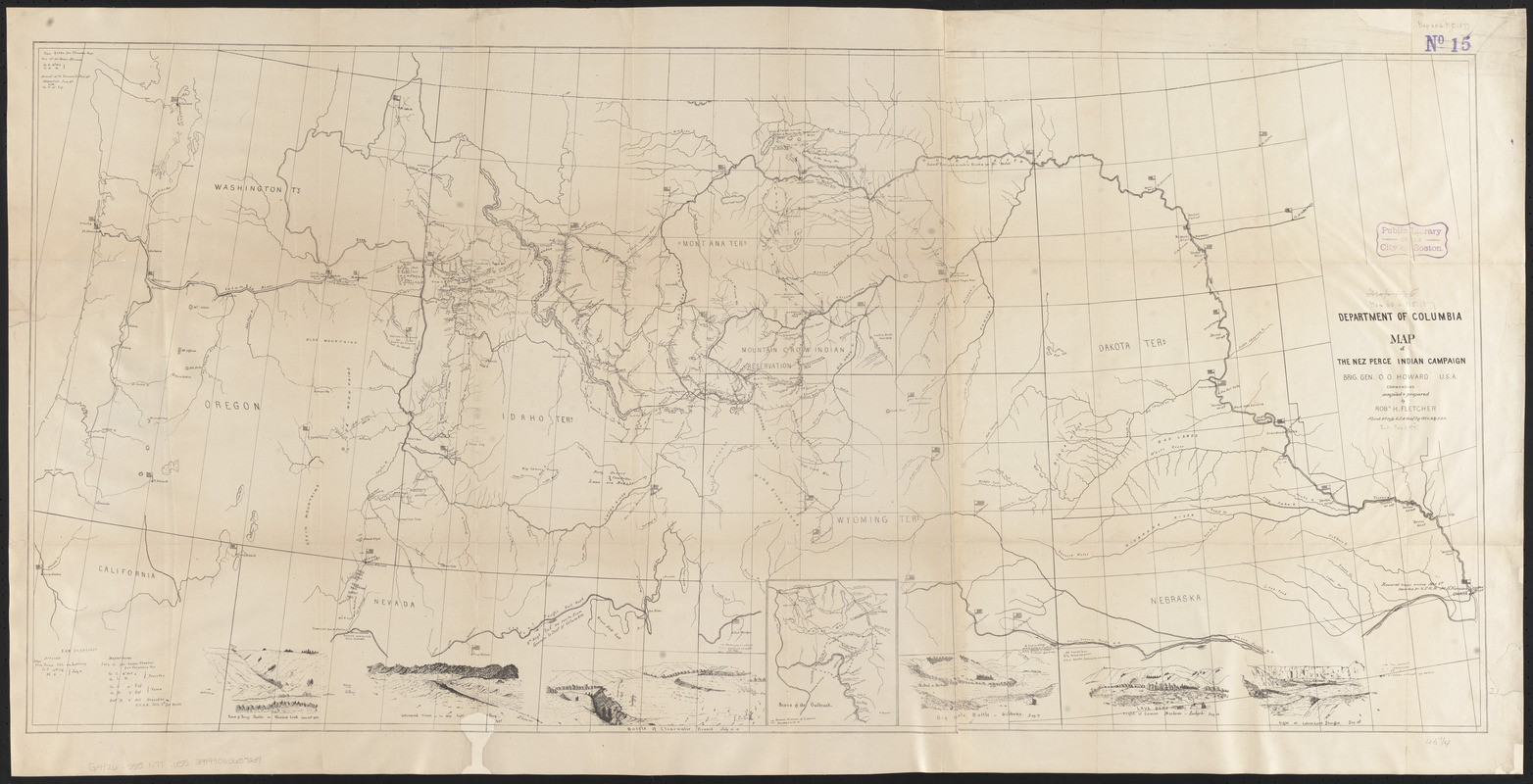

Robert H. Fletcher

"Map of the Nez Perce Indian Campaign, Brig. Gen. O. O. Howard, Commanding"

Washington, DC, 1877. Printed map, 24 x 47.25 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center. Reproduction 2019.

This military map records the Nez Perce War in 1877, one of the final campaigns of the U.S. Army against the tribal nations of the Pacific Northwest. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard, a Union Civil War leader, Commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau, and a founder of Howard University, led U.S. troops. They pursued several bands of Nimiipuu (Nez Perce) who refused to surrender their ancestral lands and move to a smaller reservation in Idaho. Threatened with forced removal, they embarked on a northward trek to find sanctuary in Canada. After a fighting retreat of 1,170 miles and 18 skirmishes and battles, they surrendered just south of the Canadian border.

National Publishing Company

"The United States of America: Including All Its Newly Acquired Territory"

Boston, 1902. Printed map, 38 x 55 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center. Reproduction 2019.

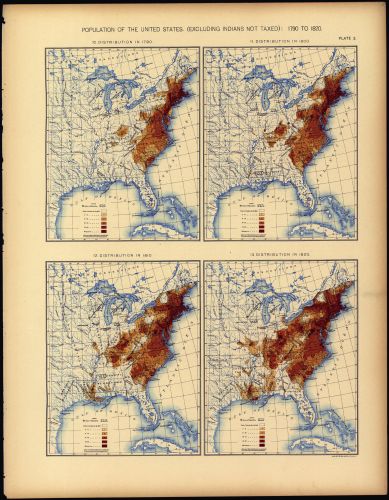

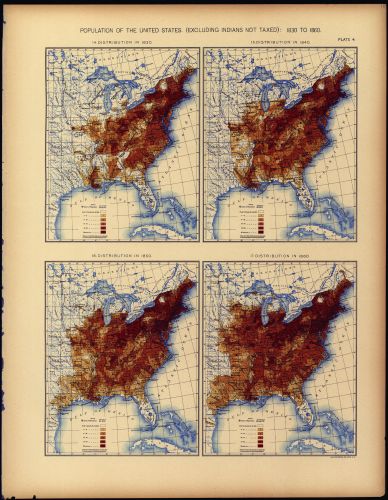

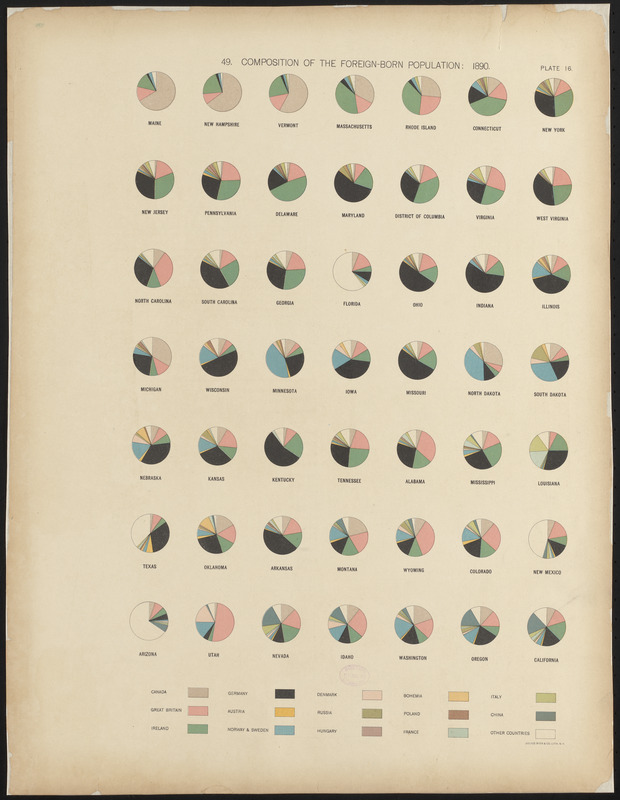

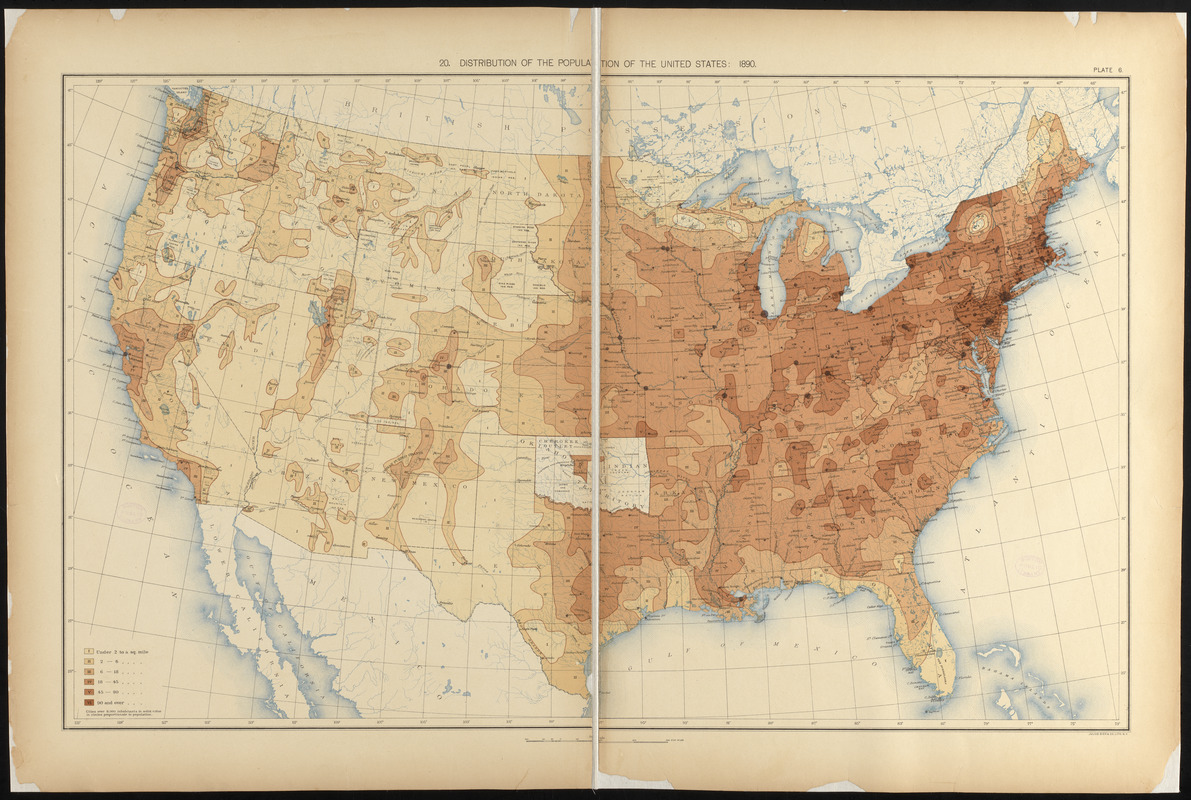

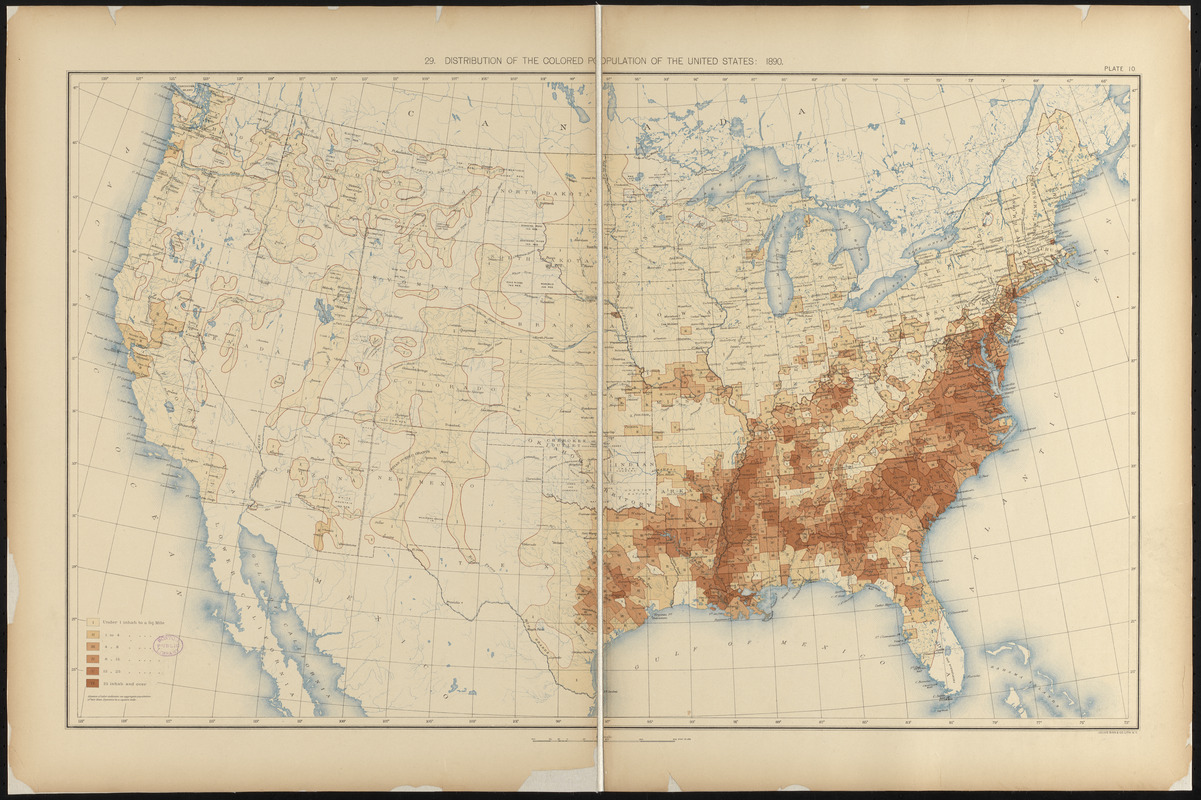

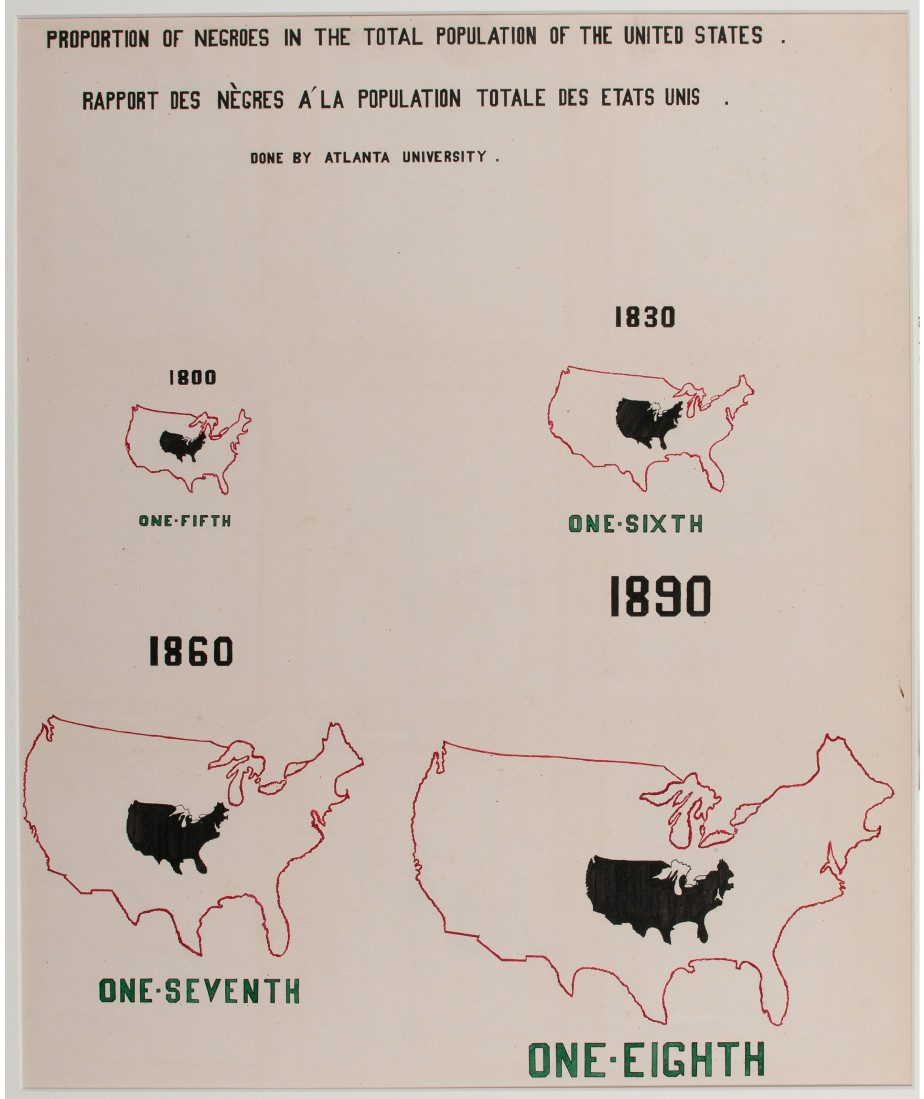

While this information-packed map summarizes the nation’s political geography and population growth after a century of territorial expansion and native removals, it also documents a new arena for empire building beyond the continent. Brightly colored boundaries outline 48 states and organized territories, as well as counties within each. Settlement in the eastern half of the country was denser than the West, which was characterized by much larger states and counties. Graphs and tables demonstrate the growth of population from 3.9 million in 1790 to over 76 million in 1900. Marginal insets depict Alaska and Hawaii (taken by a coordinated overthrow of the Hawaiian Queen just a few year prior), as well as “newly acquired territories” in the Caribbean and across the Pacific.

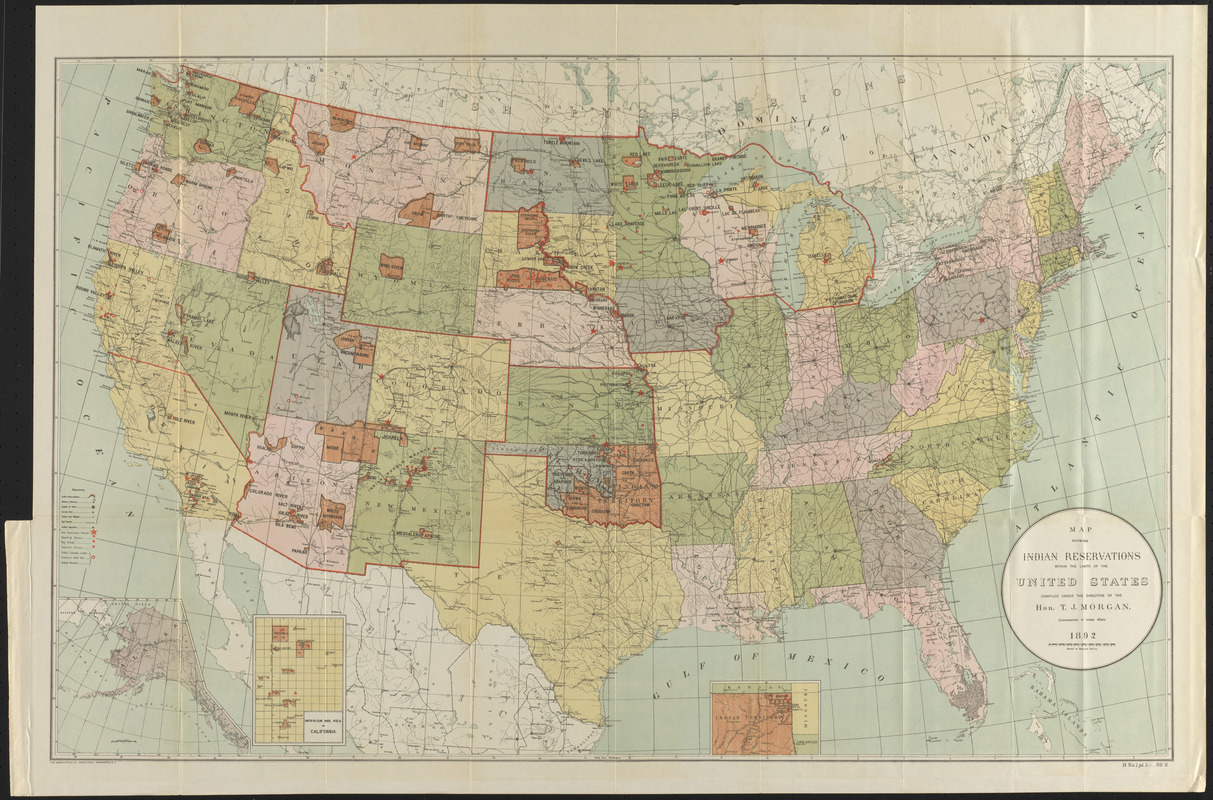

Commissioner of Indian Affairs

"Map Showing Indian Reservations within the Limits of the United States"

Washington, DC, 1892. Printed map, 38 x 55 inches. Courtesy of Lawrence Caldwell. Reproduction 2019.

By the 1890s, many Native tribes were displaced and forced to live on reservations, comprising a fraction of their homeland, on territory designated as the most undesirable for settlers or in totally different environments than originally inhabited. This map depicts the locations, sizes, and boundaries of reservations, which were usually established by treaties ratified by the U.S. Senate. In many cases Congress did not ratify treaties signed in good faith by Native peoples, and the agreed upon reservation boundaries were renegotiated to the benefit of the government and the states. In 1887, the Dawes Act (General Allotment Act) further reduced the size of reservations by permitting the federal government to assign land to individual Native families, rather than tribes. The law fragmented reservations and opened more land to non-Native settlers.

James Wilson (1763-1855)

"A New American Terrestrial Globe"

Bradford, VT, 1811. Globe, 17 x 17 x 19 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

At the beginning of the 19th century, Americans had access to globes, but they had to import them from Europe. James Wilson, who became the first to produce globes in the United States, made this globe in 1811. Rather than identifying the specific region that was part of the United States, he labeled the entire continent “America.” Wilson marked the boundaries of the eastern states and Louisiana Purchase and noted the names of several tribal nations. Since white cartographers had extensively mapped the East, the globe features more detail in that region than in the West.

James T.B. Ives (1839-1915)

"Historical Map Showing the Successive Acquisitions of Territory by the United States of America"

New York, 1896. Mechanical map, 24.5 x 34 inches. Courtesy of Barry MacLean Collection.

The boundaries of the United States transformed during the 19th century. Mapmaker James Ives created this mechanical map to help people, especially students, visualize these changes. The base map labels the tribes that occupied different regions, while the upper layers represent the territorial growth of the United States. The mechanized pieces of this cartographic puzzle include the colonies in 1776, the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, and the Gadsden Purchase in 1853. The map told a story of the seemingly inevitable process of expansion and emphasized nation-building by treaties rather than the violence of war.

1a. LAND 1800-1862: Exploring, Surveying, and Conserving the Land

To most people of European descent, the land west of the Mississippi River was unknown, although Native peoples were deeply knowledgeable about the land on which they hunted, traded, farmed, and developed communities. In the 1780s, government officials initiated the settler-colonial process of westward expansion. The maps and artifacts in this exhibition illustrate how Congress set the principles for surveying and selling public lands that had been gained through purchase, treaty, trickery, warfare, and forced removal.

Surveyors standardized the practice of dividing land into six-mile square townships providing the foundation for settlement patterns in western states. Government surveys noted the land claims of earlier French and Spanish inhabitants but failed to recognize lands claimed by Native tribes.

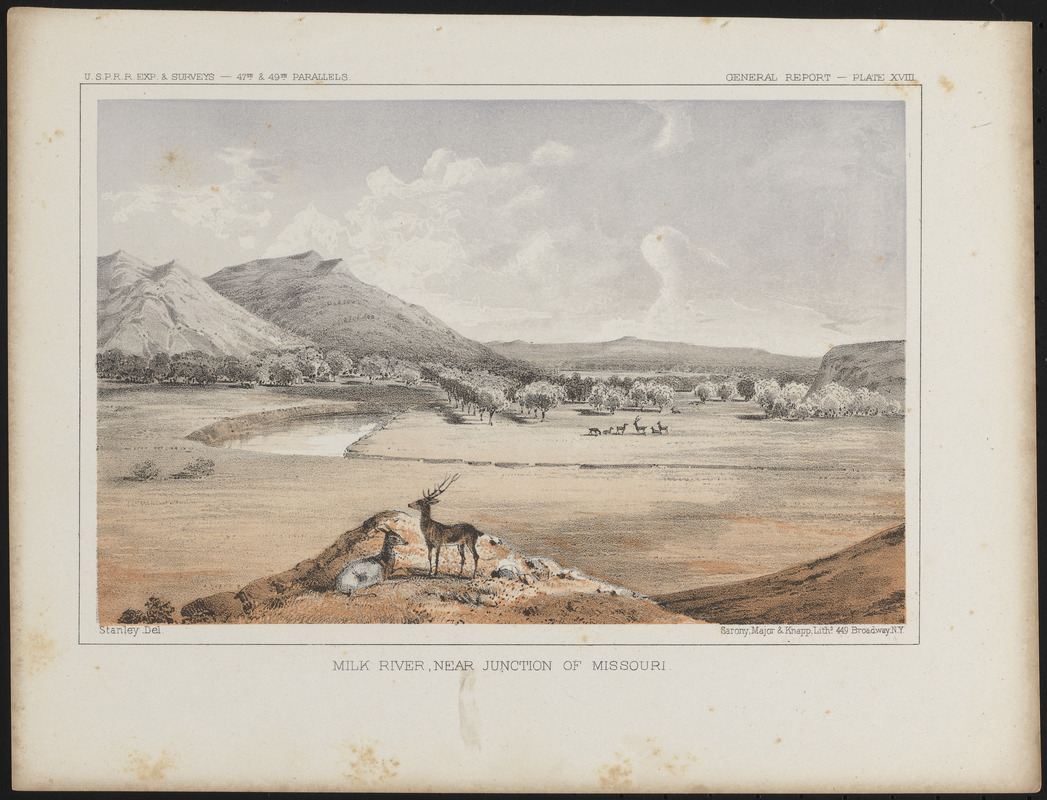

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set out to inventory and map the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase in the early 1800s. Their trip paved the way for similar government-sponsored expeditions and culminated in the 1850s with the Pacific Railroad Surveys, which mapped potential routes for the first transcontinental railroad. Each of these efforts brought back cartographic and scientific data about the inhabitants, landscape, natural resources, and wildlife. By the final third of the century, many Americans became concerned about conserving these natural resources and landscapes that were rapidly disappearing through economic exploitation.

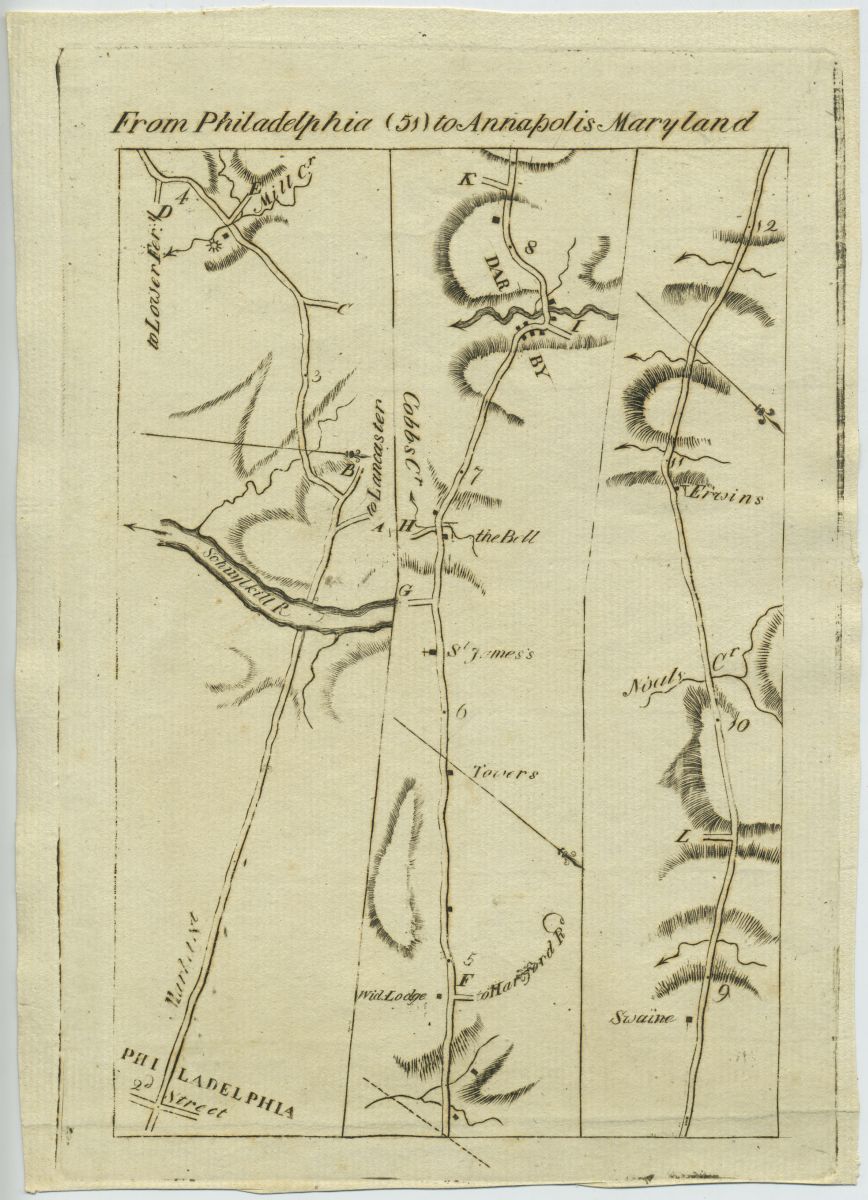

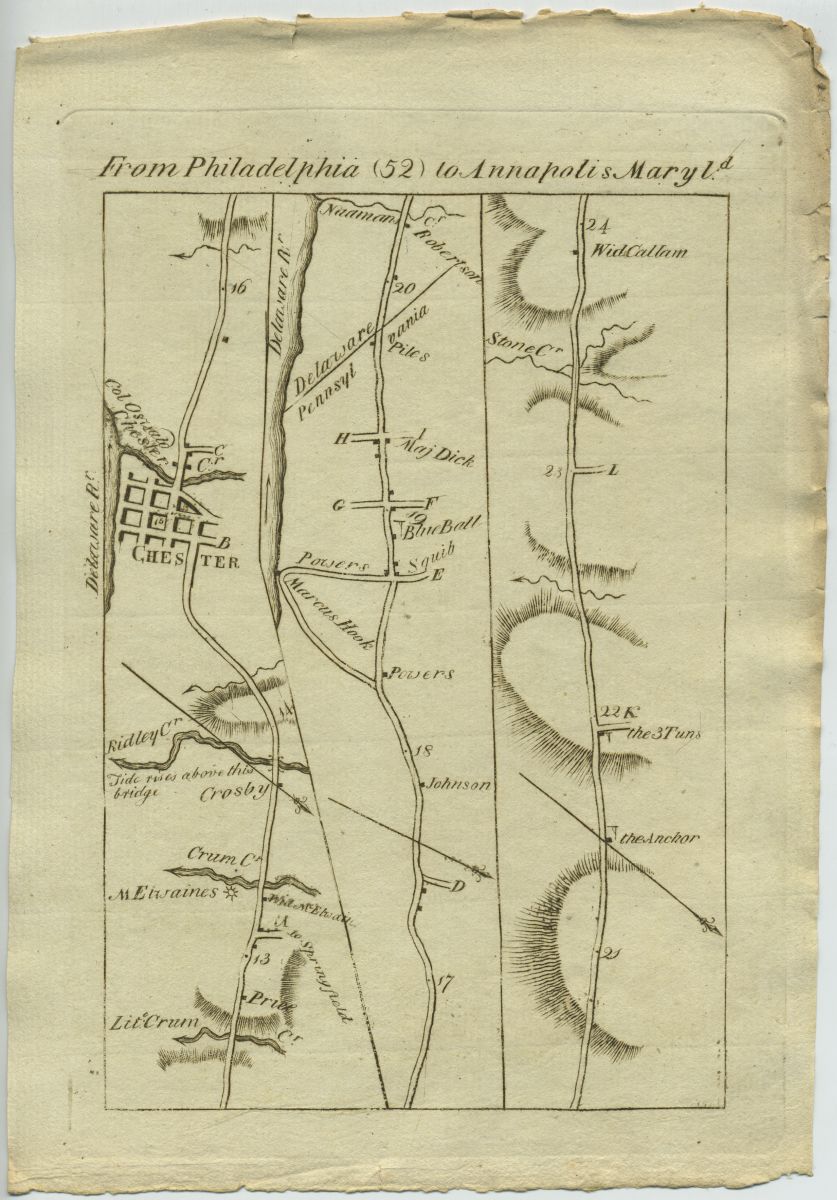

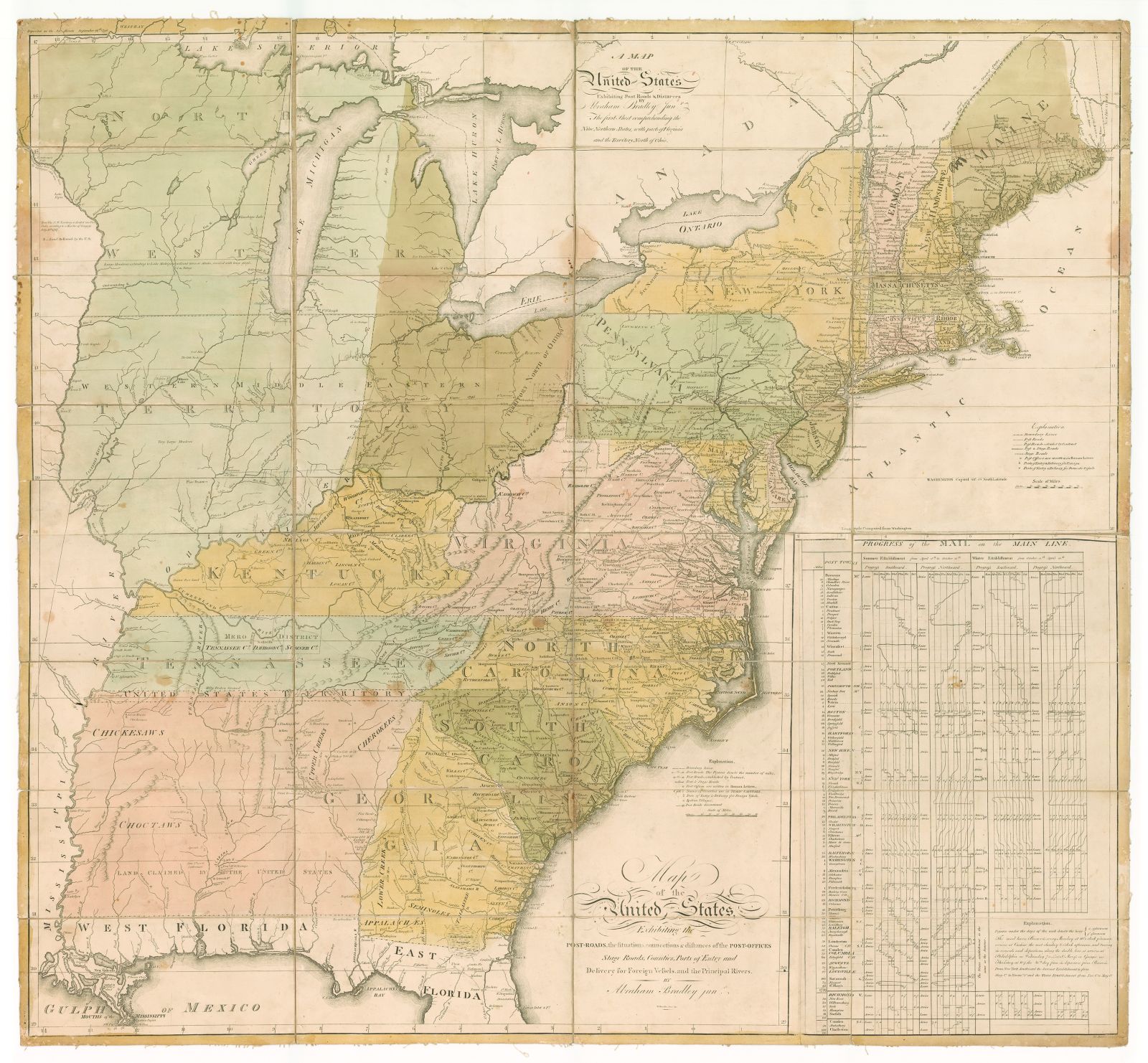

Frank Bond (1856–1940) and I. P. Berthrong

“United States Showing Routes of Principal Explorers and Early Roads and Highways”

Washington, DC, 1908. Printed map, 23.5 x 32 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center. Reproduction, 2019.

Frank Bond, a General Land Office surveyor, draftsman, and finally Chief Clerk, created this thematic, historical map that was atypical of other GLO publications. He compiled the major Spanish, Dutch, French, British, and American routes during four centuries of Euro-American exploration. This colorful presentation was overlaid on a standard base map that showed the extent of township surveys by the beginning of the 20th century. The map demonstrated the current state of geographical knowledge and suggested that by this time there was little unmapped land.

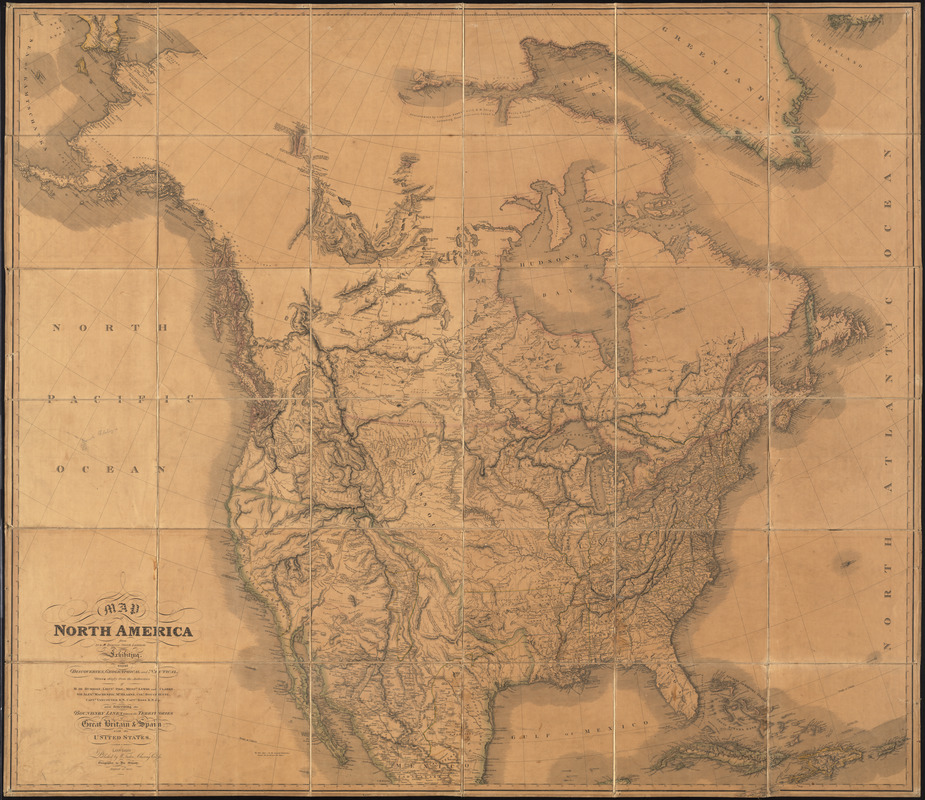

William Faden (1749–1836)

“Map of North America from 20 to 80 Degrees North Latitude: Exhibiting the Recent Discoveries …”

London, 1820. Printed map, 59 x 66 inches. Courtesy of Lawrence Caldwell. Reproduction, 2019.

This large wall map integrated topographic and hydrographic detail gained from various European and American explorations of interior North America. It included data from expeditions led by Alexander von Humboldt (northern Mexico), Alexander MacKenzie (Canadian Great Plains), and George Vancouver (Pacific northwest coast), as well as Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, and Zebulon Pike, all of whom were commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson to explore the newly acquired Louisiana Territory. This accumulated knowledge demonstrated that the western part of the continent was not dominated by a single mountain range as was previously hypothesized, but by a complex series of ranges that came to be known as the Rocky Mountains.

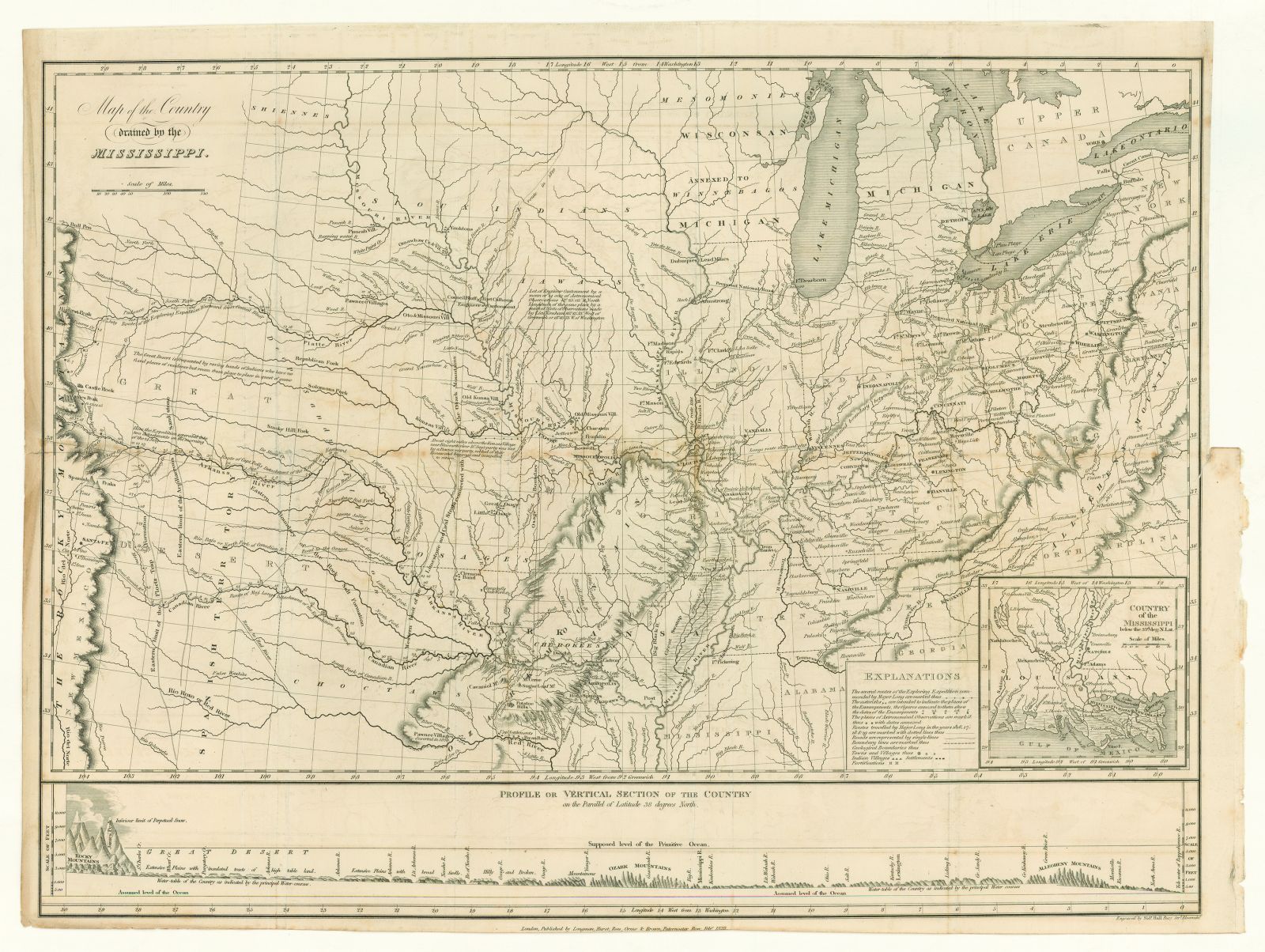

Edwin James (1797–1861)

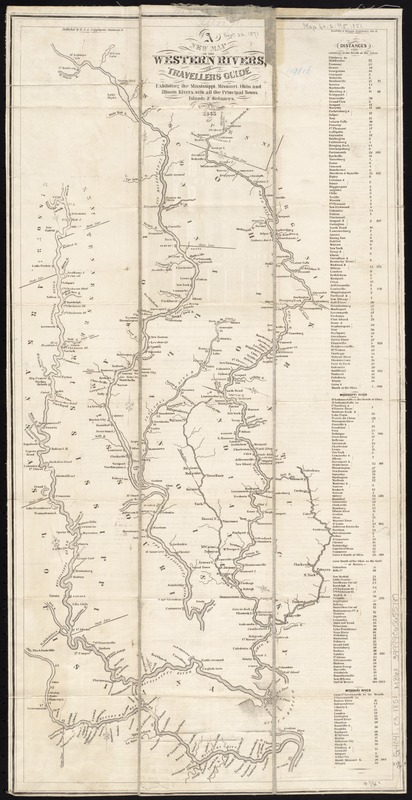

“Map of the Country Drained by the Mississippi,” in “Account of an Expedition from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains … under the Command of Major Stephen H. Long ...”

London, [1823]. Printed map, 16 x 21 inches. Courtesy of Barry MacLean Collection.

Maj. Stephen H. Long’s scientific expedition (1819–1820) continued the tradition of U.S. Army-sponsored exploration. The expedition culminated in a published narrative with a map that delineated Long’s route from St. Louis up the Missouri and Platte Rivers to the Rocky Mountains. Information for the eastern half of the map was borrowed from commercial sources, while the western half corrected geographical errors made by previous expeditions. However, Long incorrectly characterized the High Plains as the “Great American Desert” (see southwestern quarter of map). This misconception may have deterred Euro-American settlement of the Great Plains during the early and mid-19th century.

Edwin James (1797–1861)

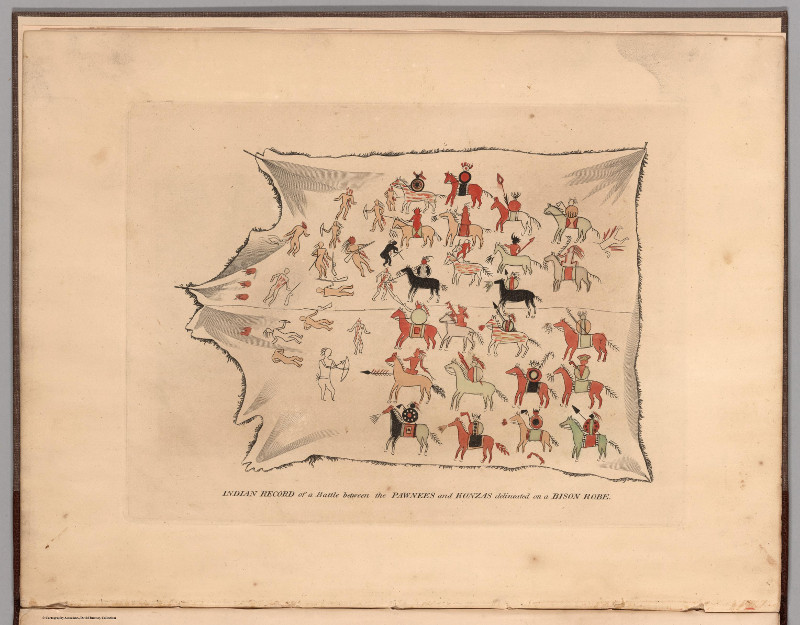

“Indian Record of a Battle between the Pawnees and the Konzas. A Facsimile of a Delineation upon a Bison Robe,” in “Account of an Expedition from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains …”

London, [1823]. Print, 6 x 7.5 inches. Courtesy of David Rumsey Collection. Reproduction, 2019.

Rather than relying on Native knowledge, Long’s party included scientists and artists for the first time. Although artist Samuel Seymour drafted more than 150 sketches, the report published only eight, which documented landscapes and encounters with Native people. The final and most unique plate reproduced a buffalo robe showing a battle between Pawnee and Kansa (Kansas) warriors. The design provides a contrast with Euro-American methods of recording events in time and space, depicting the spatial interrelationships of individuals drawn in profile to record the conflict.

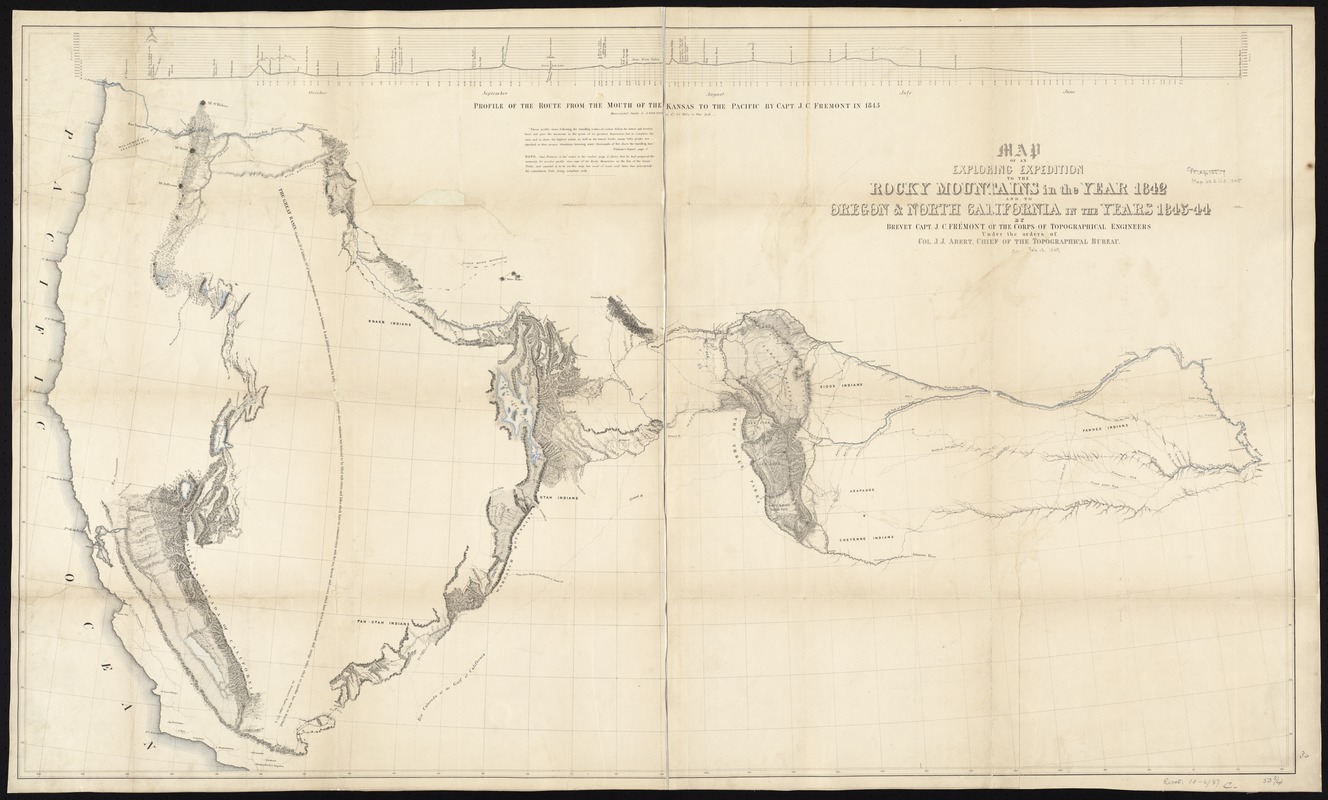

John C. Frémont (1813–1890)

“Map of an Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains … and to Oregon & North California …”

Washington, DC, 1845. Printed map, 59 x 66 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

During the 1840s, Americans became interested in the Far West as they settled the Oregon Territory and entered the Mexican-American War. One American explorer who made major contributions during this period was John C. Frémont, who led five scientific expeditions. Charles Preuss, a German immigrant and the expedition’s cartographer, prepared this map depicting only the geographic information collected. Frémont’s official reports, written with the assistance of his wife Jessie (daughter of expansionist-minded Missouri senator Thomas Hart Benton), gave “manifest destiny” a popular text. Advocates of “manifest destiny” believed it was the nation’s mission and preordained right to spread American institutions and culture, thus justifying a policy of territorial expansion.

John Disturnell (1801–1877)

“Mapa de los Estados Unidos de Méjico”

New York, 1846. Printed map, 30 x 37 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

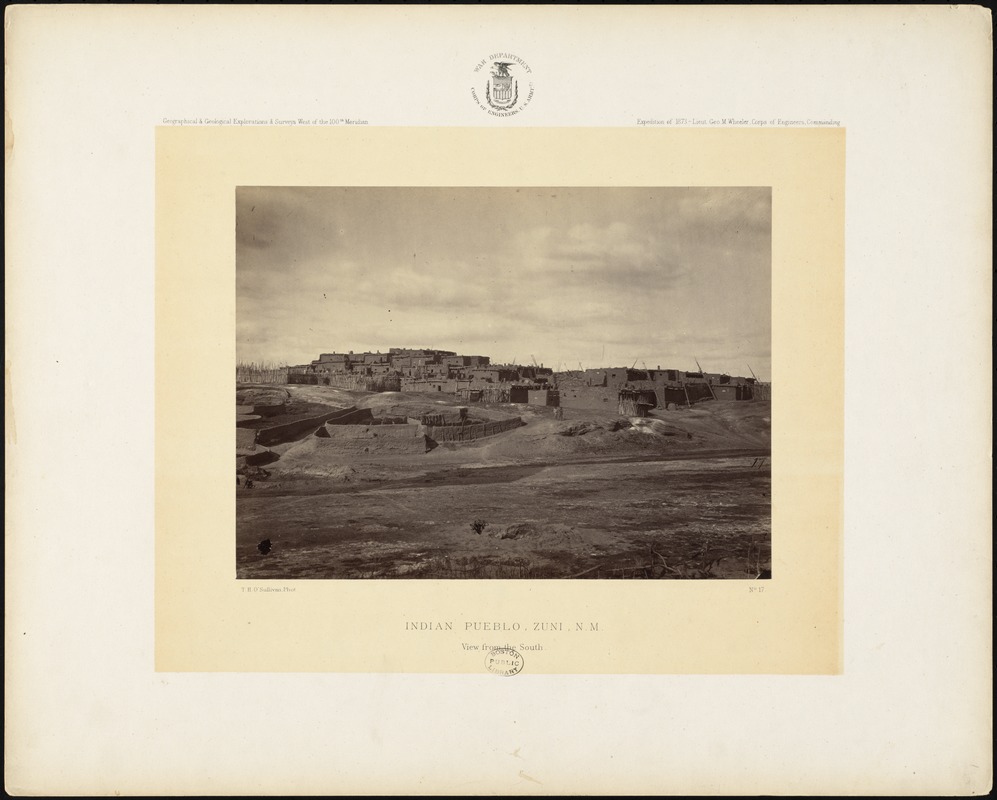

Published a year after the annexation of Texas, at the outbreak of the Mexican-American War, this map depicts the northern region of Mexico (today part of the United States). It reveals a cultural landscape with both Spanish and Native settlements. Besides the Spanish settlements in southeastern Texas, there were three other clusters in this northern region – the upper Rio Grande (New Mexico), southern Arizona, and the California coast. While some Spanish settlements had been established more than a century earlier, Spanish culture was imposed on numerous Native groups already living in the area including the Pueblo, Numunu (Comanche), N’Dee (Apache), Hopitushínumu (Hopi), and Diné (Navajo).

VIEWPOINT: This map offers a great example of the fluidity of geography, as we can see how its meaning had shifted and would shift again. Lost in the designs of nation-states are the numerous indigenous geographies (still visible in maps like this) that remain in place and persist to this day.

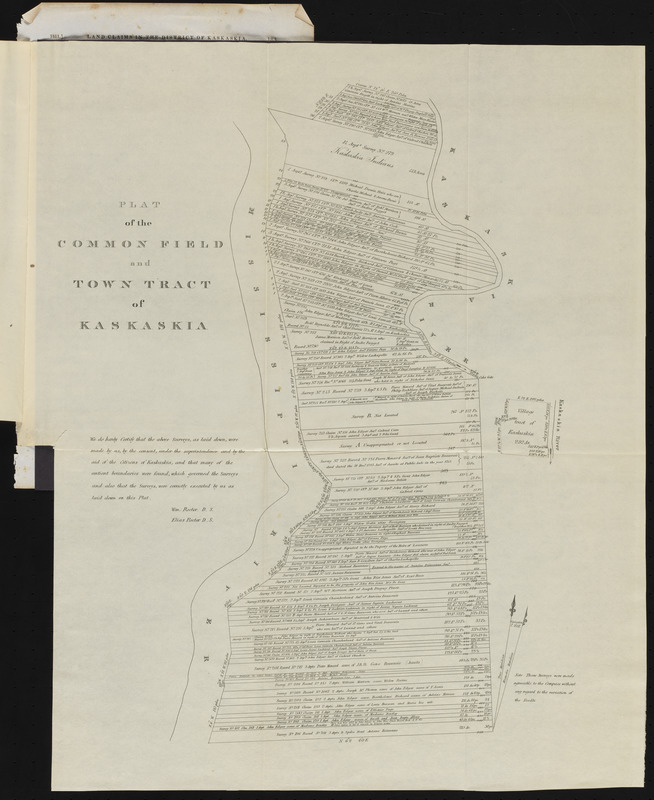

William Rector (1778–1827) and Elias Rector (d. 1822)

“Plat of the Common Field and Town Tract of Kaskaskia”

Washington, DC, 1807. Printed map and report, 20 x 17. Courtesy of Lawrence Caldwell. Reproduction, 2019.

U.S. officials agreed to adjudicate land grants, known as private land claims, that had been made by French, British, Spanish and Mexican governments to their settlers. The first of these transactions were for early French settlements, such as the village of Kaskaskia shown here, later named the capital of the Territory of Illinois. On this map, the Common Field is divided into long narrow lots, a common characteristic of French settlements. These irregular surveys were incorporated into the rectangular grid pattern.

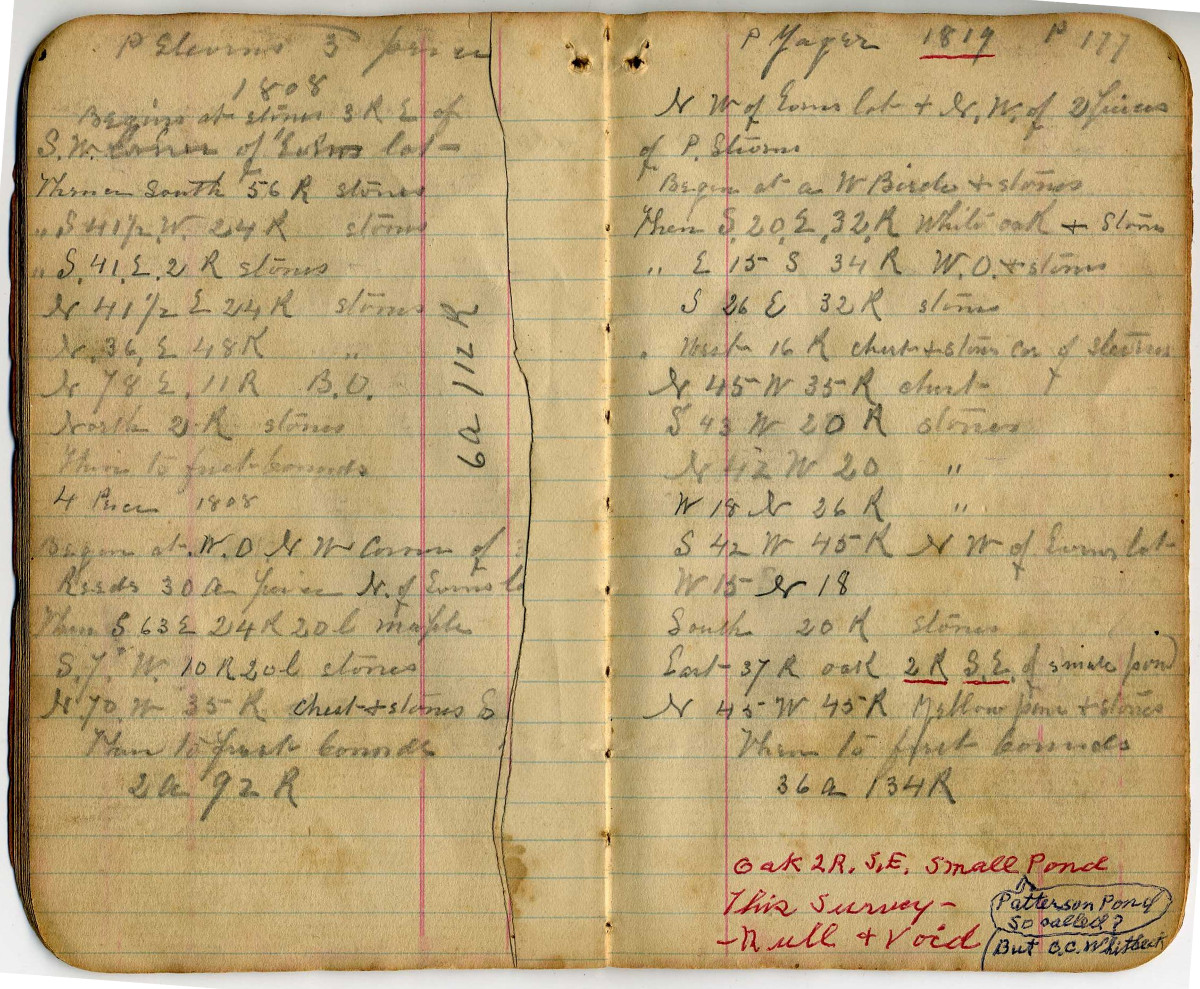

Horace Minot Pool (1803–1878)

“Surveyor’s Compass, Chain and Chain Pins, and Field Notes”

Easton, MA, 1841-1878. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

Surveyors determined angles or direction in simple cadastral or property surveys using a compass, like this one made in Easton, Massachusetts. They measured distance with an iron-link chain of 100 links or 66 feet, using a unit called a pole or rod which equaled 16.5 feet. An example of surveyor’s field notes documenting the “metes and bounds” of a survey opens with “Begin at a W. Birch and stones, then S 20 E 32 R. White oak and stones.”

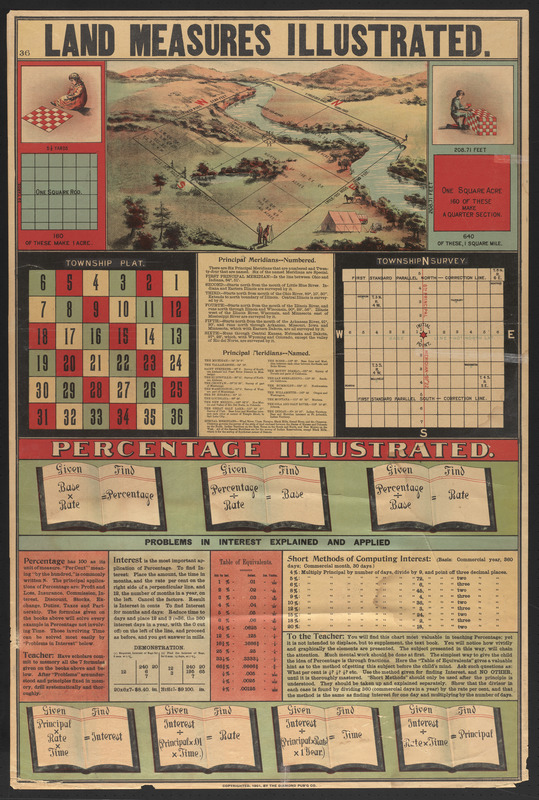

Diamond Publishing Co.

“Land Measures Illustrated”

Minneapolis, 1901. Broadside, 41 x 27.5 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

This educational poster illustrates the structure of General Land Office township surveys. The top scene depicts surveyors laying out a single section, measuring one mile by one mile and containing 640 acres. The diagram labeled “Township Plat” demonstrates the division of a township into 36 sections, while the “Township Survey” diagram explains that townships are identified in relation to a base line and meridian (representing an X-Y axis). Each parcel of land has a unique numerical identifier such as the 40-acre tract where the surveyors stand could be identified as the SE 1/4 of the SE 1/4 of Section 1, Township 3 North, Range 4 West, 6th Principal Meridian.

VIEWPOINT: These divisions remind us of the harmful game of wrongful land dispossession. For Native people, these squares represent a systematic disruption of our ancestral ways of life. This diagram reflects the colonial concept of land ownership: packaged up in little squares, as though one can compartmentalize a way of life and sell it.

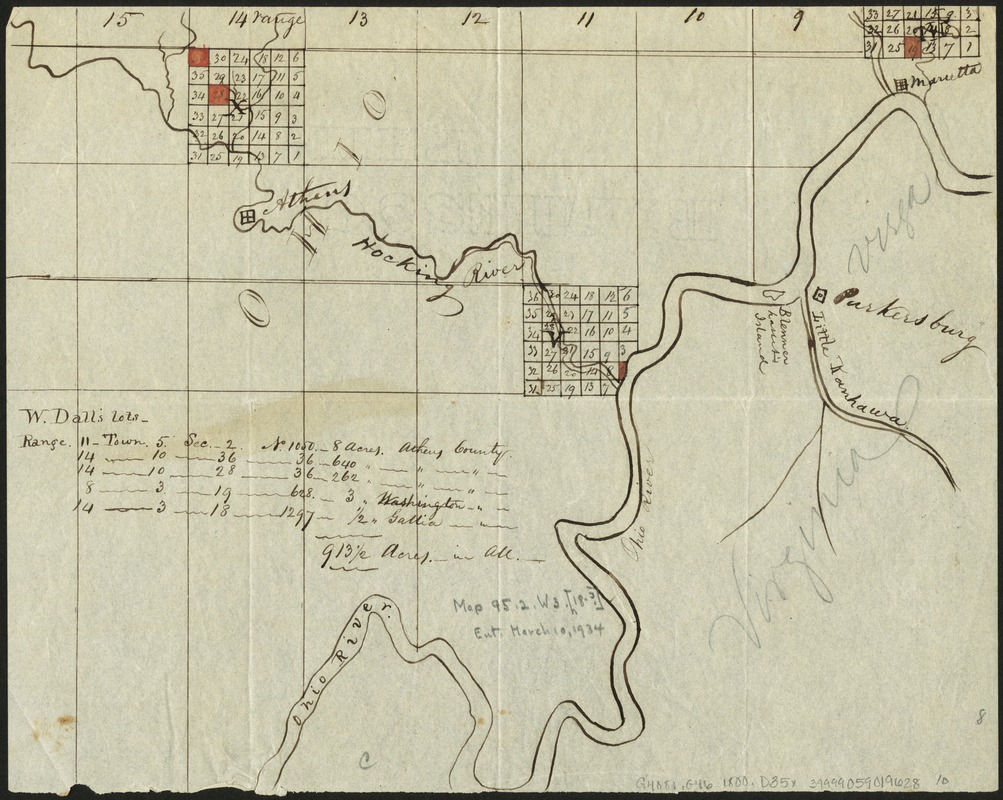

William Dall (fl. 1800)

“Map of W. Dall's Lots in Athens County, Washington County, and Gallia County, Ohio”

1800. Manuscript map, 8 x 10 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

This small manuscript map served as a personal record of one individual’s land holdings. It highlights the grid pattern that was characteristic of public land surveys initiated by the Land Ordinance of 1785. These townships were part of the Ohio Company’s purchases in southeastern Ohio. This private land company, composed of Boston investors, established Marietta as the first Euro-American settlement in the Northwest Territory. The map noted that William Dall owned five parcels of land in four townships, totaling over 900 acres.

William Woodruff (fl. 1817–1833), after Alexander Bourne (1786–1849) and Benjamin Hough

“A Map of the State of Ohio from Actual Survey”

Cincinnati, 1831. Printed map, 51 x 48 inches. Courtesy of Lawrence Caldwell.

Ohio, the 17th state, was the first carved out of the Northwest Territory. Survey grid patterns based on 5- and 6-mile square townships were first implemented here, in addition to traditional irregular metes and bounds surveys in the Virginia Military District. To administer surveying and sales, over a dozen private land companies, military land districts, and congressionally-authorized districts were created. By 1832 when this large wall map was updated, surveying had been completed. County boundaries and township perimeters are marked. The cartouche promotes agriculture and river transportation with a scene of a farm overlooking the Ohio River.

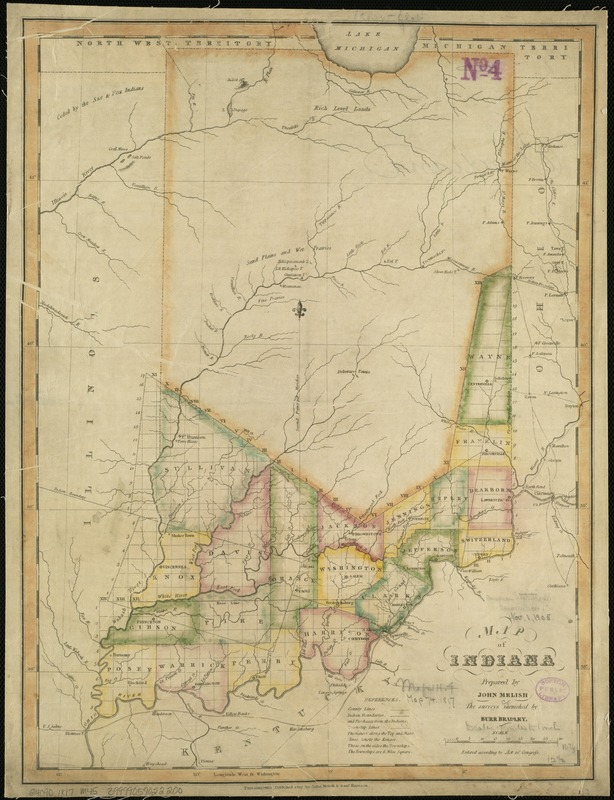

John Melish (1771–1822) and Burr Bradley

“Map of Indiana”

Philadelphia, 1817. Printed map, 18 x 13.5 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

Indiana Territory (“Land of Indians”) was similarly carved out of the Northwest Territory in 1800. Published in 1817, a year after Indiana’s statehood, this map indicates that officials had divided the southern third of the state into counties and townships. Numerous tribal nations, including the Myaamiaki (Miami), Kiikaapoi (Kickapoo), Lenape (Delaware), Shawnee, and Neshnabé (Potawatomi) inhabited the region. The map identifies land cessions before 1817 with dashed lines. From the 1820s through the 1840s these tribal communities were forcibly relocated, most often to reservations in the Great Plains or to Canada.

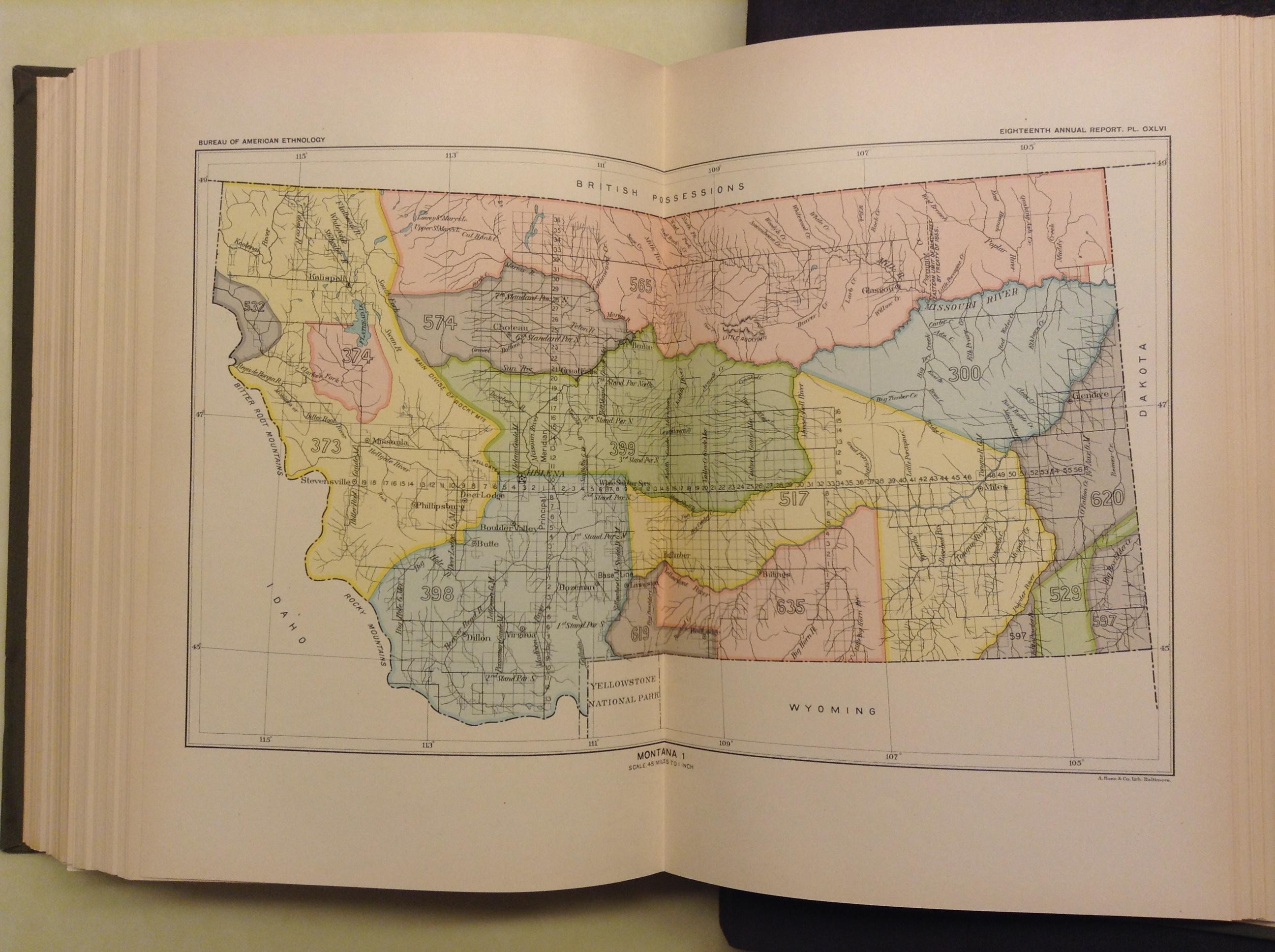

Charles C. Royce (1845–1923)

“Montana 1,” from “Indian Land Cessions in the United States, 1784-1984”

Washington, DC, 1899. Printed map, 11.5 x 14.5 inches. Courtesy of Ronald Grim.

By the 1890s, the U.S. government seized over 1.5 billion acres of Native land by way of treaty, coercion, military force, and executive order. Tables in this compendium itemize over 700 land cessions and treaties enacted between 1784 and 1894, while 67 maps delineate the boundaries of each transaction. For example, the yellow and pink districts in western Montana (numbered 373 and 374) refer to the 1855 Treaty of Hellgate, negotiated with the Séliš (Flathead), Kootenai (Kootenay), and Q'Lispé (Upper Pend d’Orielles). Through a contentious negotiation process mired in mistranslation and differing expectations, the tribes ceded their lands and became dissatisfied with enforcement of the treaties. Hostilities broke out in 1858.

VIEWPOINT: “Cede” is a very gentle term to describe a deeply violent, forced, and uneasy process. As Native groups suffered losses from epidemics and the destruction of their food sources, they relinquished their lands to the U.S. government, often as a final resort. Native groups were forced to relocate from their homelands, either by treaty or executive orders promising them abundant resources in exchange for territory – none of which were fully realized.

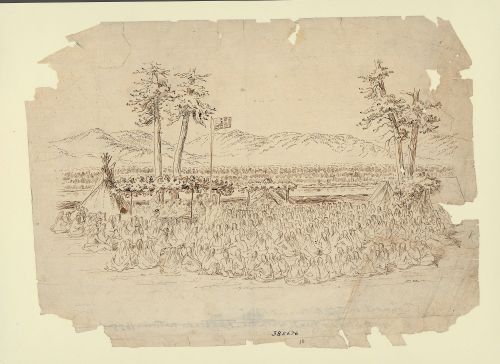

Gustavus Sohon (1825–1903)

“Feast for the Indian Council”

1853. Manuscript pencil drawing, 8 x 10 inches. Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution National Anthropological Archives. Reproduction, 2019.

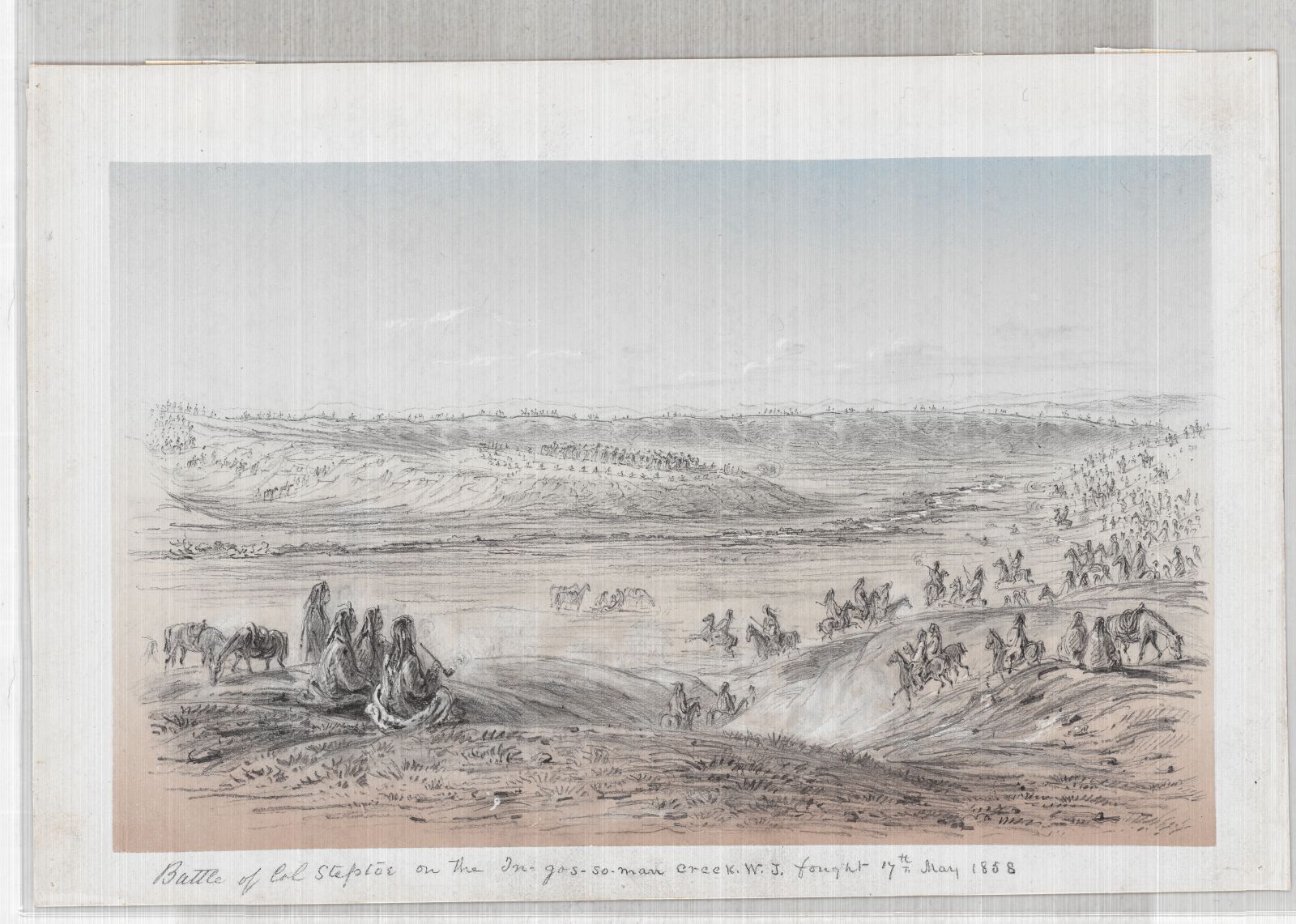

Gustavus Sohon (1825–1903)

“Battle of Col. Steptoe on the In-gos-so-man Creek, W.T., Fought 17th May 1858”

1858. Manuscript pencil drawing, 6.75 x 10 inches. Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LOT 2528 (F) [P&P]. Reproduction, 2019.

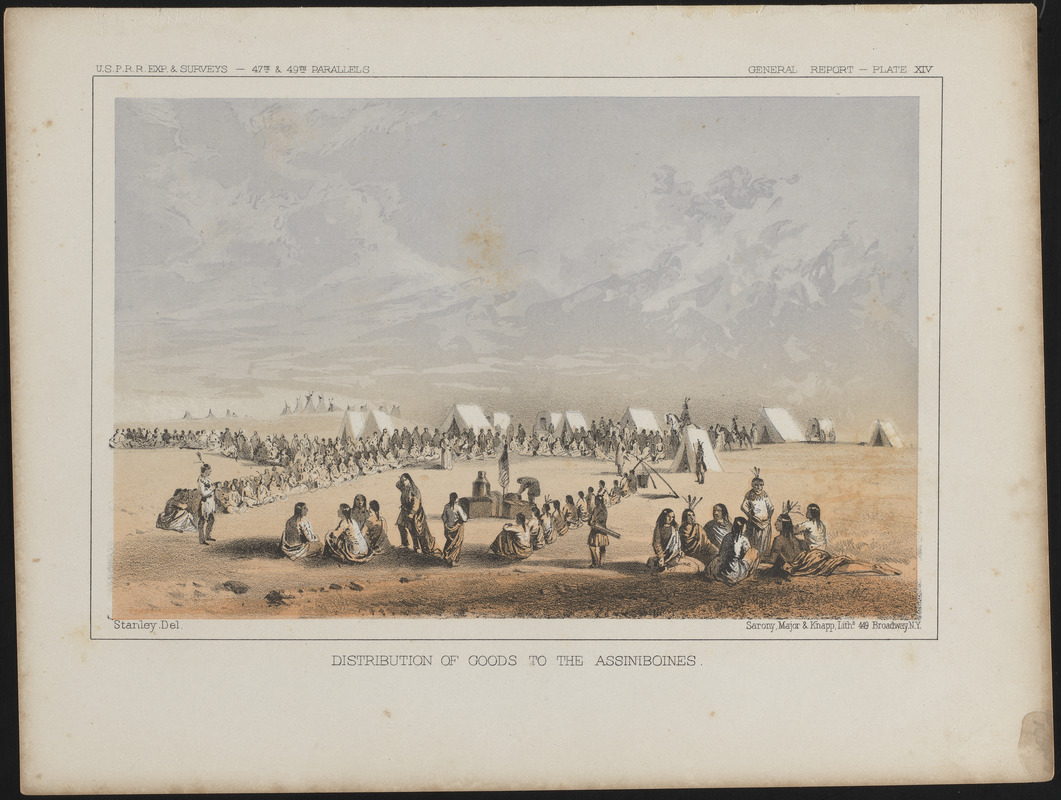

Isaac Stevens, leader of the Northern Pacific Railroad Survey and Washington’s territorial governor, negotiated several treaties during the 1850s to help justify the construction of a northern railroad route and to entice Americans to move to the Pacific Northwest. Two pencil sketches, prepared by Gustavus Sohon, a German immigrant who served as an artist and interpreter with Stevens, depict scenes from this period. In 1855, he produced this pencil drawing documenting Stevens’ negotiation with the Flathead Treaty Council. In 1858, he accompanied the campaign against the Spokane, Schitsu'umsh (Coeur d'Alene), and Palouse. His second drawing records the defeat of U.S. Army troops by a combined force of several Native groups.

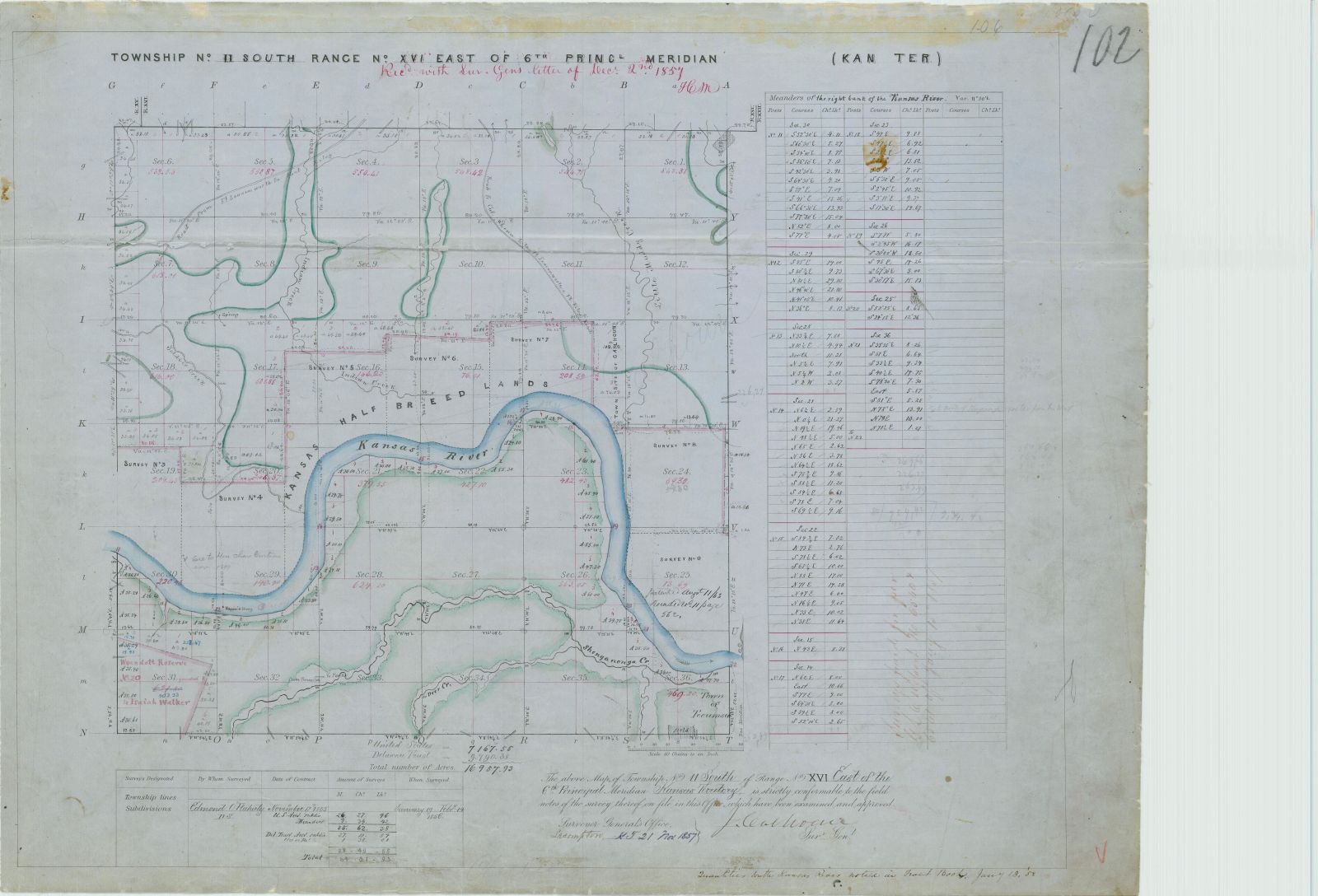

John Calhoun (1806–1859)

“Township no. 11 South, Range no. XVI East of 6th Princl. Meridian”

1857. Manuscript survey plat, 17 x 22 inches. Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 49, Kansas Headquarter Plats. Reproduction, 2019.

The General Land Office produced manuscript survey plats for each individual township. Their primary purpose was to outline the boundaries of the six-mile square township and each of the 36 sections. Surveyors often noted natural and man-made features that crossed or were near the surveyed lines. In this Kansas example, the Kansas River and tributary streams dominated the landscape. Green lines marked the boundary between woodland and prairie, while existing roads, farmsteads, and town sites were also mapped. One unusual feature is seven 640-acre tracts, identified as Kansas half-breed lands, which were allotted to individuals of mixed Kaw (Kanza) and European ancestry.

VIEWPOINT: Full breed lands did not exist because full breeds were not considered human enough to be land owners. Half breeds, or mixed race Natives were considered to be partially human and able to own land, while Natives with no European ancestry were less than human, not worthy of land possession.

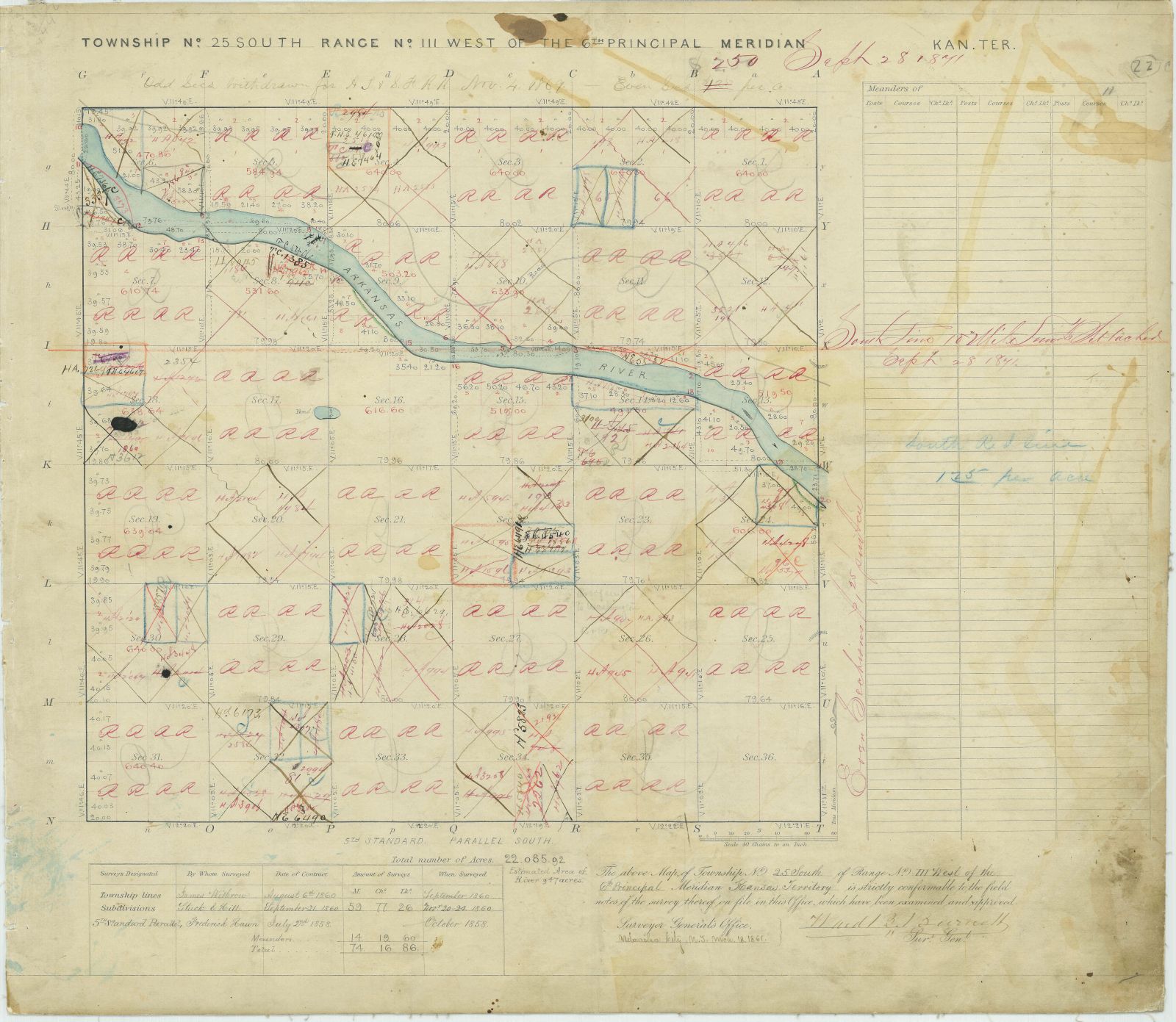

Ward Burnett (1811–1884)

“Township no. 25 South, Range no. III West of the 6th Principal Meridian”

1861, with later annotations. Manuscript survey plat, 16.5 x 19 inches. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 49, Kansas Local Office Plats. Reproduction, 2019.

The Homestead and Pacific Railroad Acts, both passed in 1862, dramatically changed the process for granting public lands. The former allotted 160 acres to white settlers, as well as freed men and women, who would improve land within five years of selection. The latter authorized construction of the first transcontinental railroad and established the principle of giving alternating sections (640 acres) to railroad companies. For example, this township was surveyed in the late 1850s, but most of the land was not selected until the 1870s. Alternating sections marked with “RR” were granted to a railroad company, while those sections patented through the homesteading process are indicated by an X.

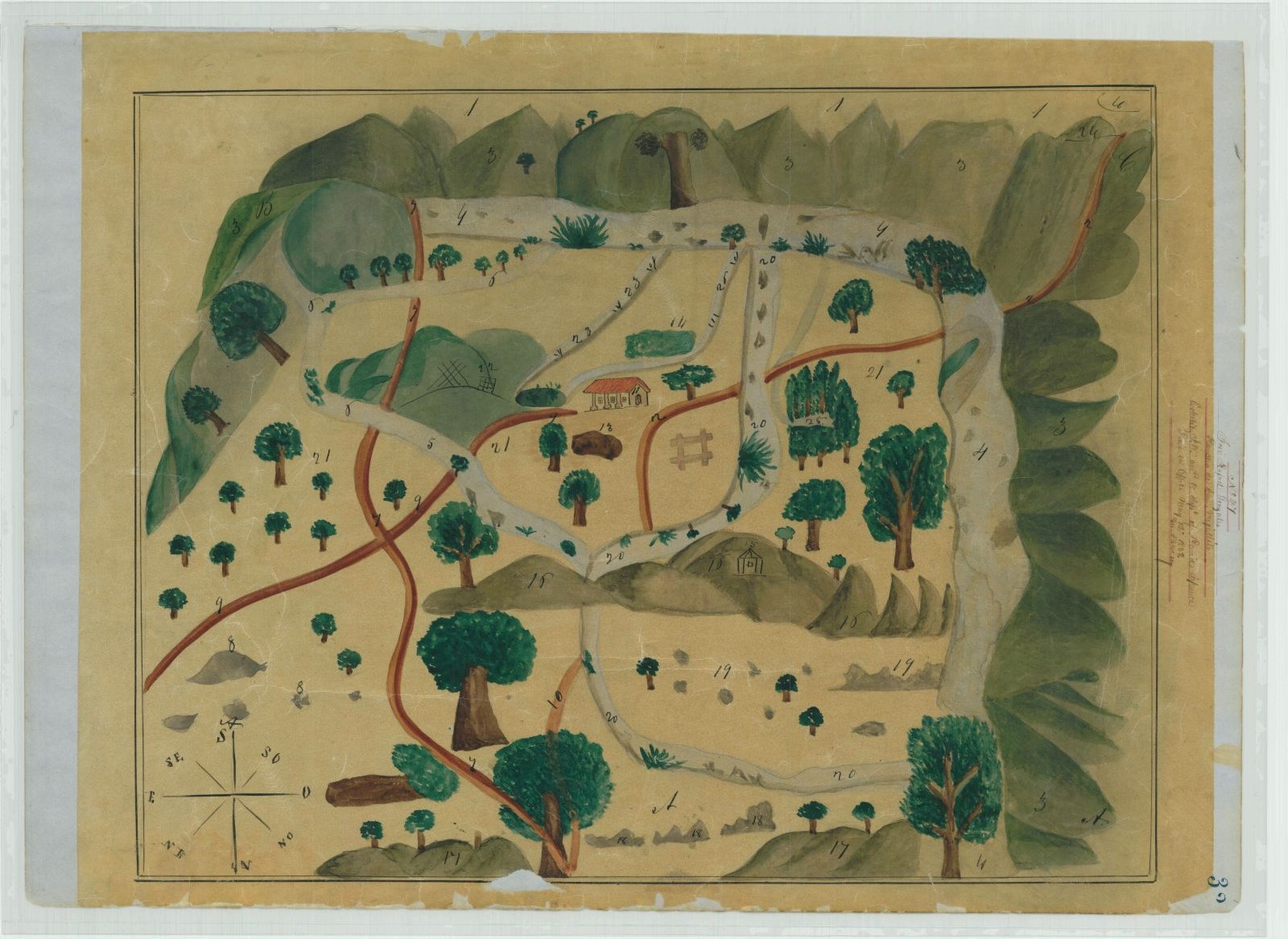

José Rafael Gonzales (fl. 1852)

“Diseño for Rancho San Miguelito”

1852. Manuscript drawing, 12 x 17 inches. Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 49, California Private Land Claims, Diseños. Reproduction, 2019.

The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican-American War and ceded much of this southwestern territory to the United States. The federal government agreed to honor Spanish and Mexican land grants. Claimants in California had to submit a documentary case file (expediente) with a description and map (diseño) of the tract. Displayed here is a diseño for more than 22,000 acres granted by the Mexican governor in 1841 and finally approved by the U.S. government in 1867.

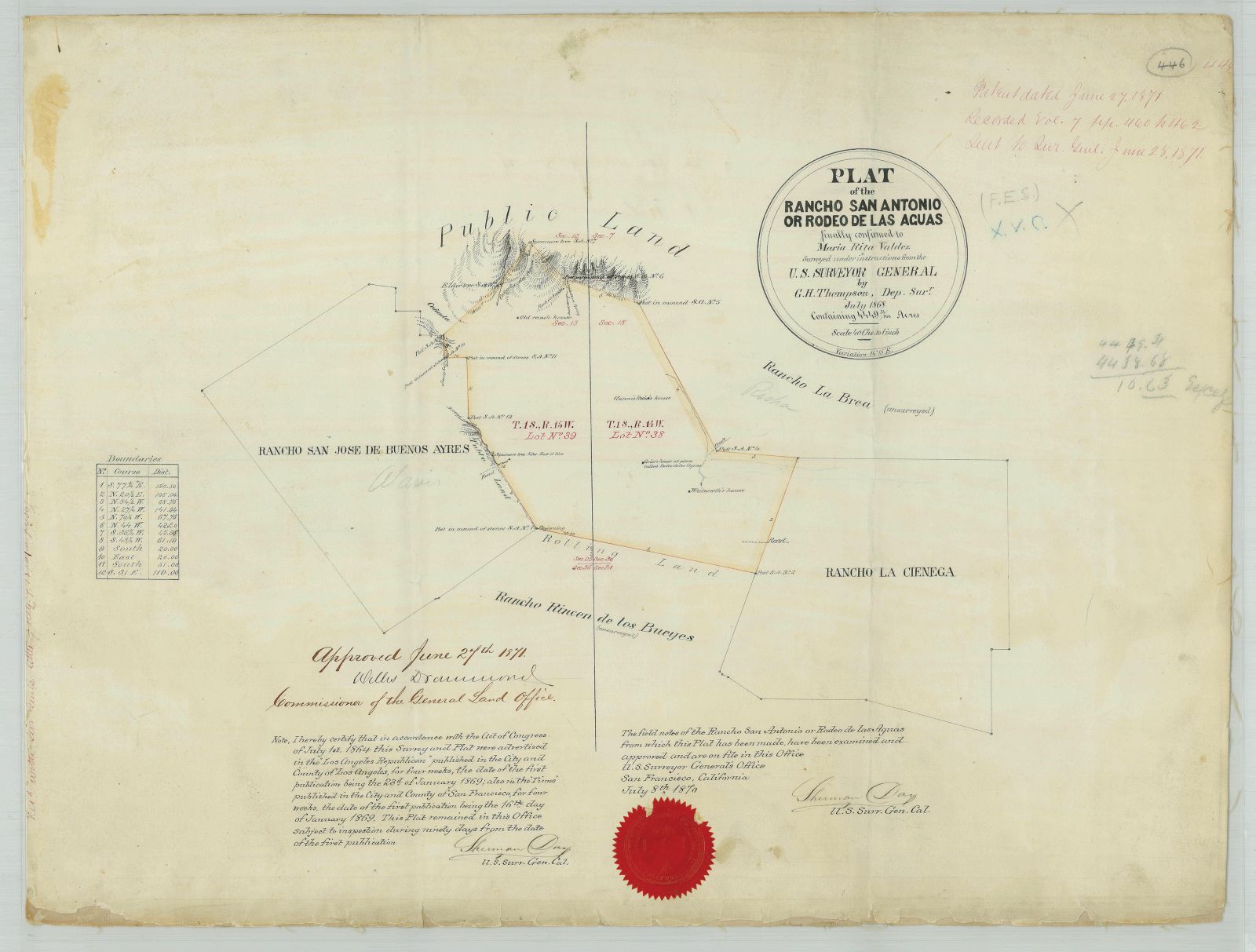

George H. Thompson (fl. 1870)

“Plat of the Rancho San Antonio or Rodeo de las Aguas, Finally Confirmed to Maria Rita Valdez”

1870. Manuscript survey plat, 19 x 25.5 inches. Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 49, California Private Land Claims, Survey Plats. Reproduction, 2019.

In California, Spanish settlements extended along the California coast from San Diego to San Francisco. Over 800 private land claims required adjudication, reflecting a variety of settlements identified as presidios (forts), pueblos (towns), missions, and ranchos. The latter were large land holdings that ranged from 4,000 to 40,000 acres and rarely had precise boundaries. Displayed here is the final survey for Rancho Rodeo de las Aguas, originally granted in 1838 to Maria Rita Valdez, a granddaughter of one of the original settlers of Los Angeles. The grant was finally surveyed and approved by the General Land Office in 1871, although she sold the property in 1854.

1b. LAND 1862-1900: Surveying and Conserving the Land

In the late eighteenth century, government explorers and surveyors initiated the settler-colonial process of westward expansion. In the 1780s, Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance to establish the process for admitting new states. The laws also outlined the principles for surveying and selling public lands that the United States had gained through purchase, trickery and obfuscation, warfare and other forms of violence, forced removal, and treaty. Surveyors standardized the practice of dividing land into six-mile square townships that provided the foundation for settlement patterns in western states. Government surveys noted the land claims of earlier French and Spanish inhabitants and aimed to prove the cession of lands occupied by Native tribes.

From 1803 to 1805, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set out to inventory and map the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase. Their trip paved the way for similar expeditions and culminated in the 1850s with the Pacific Railroad Surveys, which mapped potential routes for the first Transcontinental Railroad. Each of these efforts brought back cartographic and scientific data about the inhabitants, landscape, natural resources, and wildlife. By the final third of the century, many Americans had become concerned about conserving these natural resources and landscapes that were rapidly disappearing through economic exploitation.

For Kids

After the Civil War, large numbers of Americans raced west in search of land and riches. Native nations and parts of the natural world, like forests and bison, suffered great losses as a result. Trees became lumber and the search for fossil fuels and precious metals scarred the land. At the same time, some Americans supported the idea of National Parks to preserve the West’s most dramatic landscapes.

- Can you find maps and images in this section that tell a story about what was gained as Americans expanded across North America?

- Can you find maps and images that tell a story about what was lost?

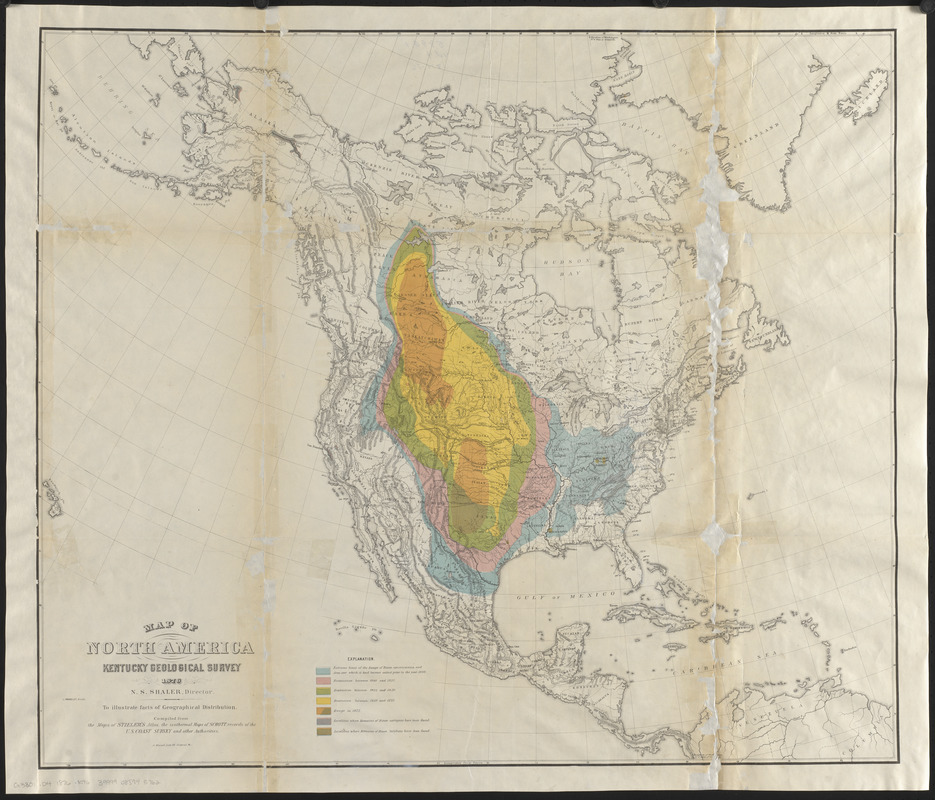

Joel A. Allen (1838-1921)

“Map of North America,” from The American Bisons, Living and Extinct

Cambridge, MA, 1876. Printed map, 29.5 x 25 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center. Reproduction 2019.

This colorful map documents the diminishing range of bison during the 18th and 19th centuries. It accompanied an 1876 report prepared by Joel Allen, an American zoologist, mammalogist and ornithologist at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. The map shows the distribution of bison before 1800 (blue), 1825 (pink), 1850 (green), 1875 (yellow) and afterwards (orange). To emphasize the influence of migration and railroad construction on bison, the map also delineates the routes of the Emigrant Trail, the Union Pacific Railroad, and other railroads in Kansas and Colorado.

Viewpoint: This map only shows trail and railroad construction, but those were not the major reasons for the demise of bison in the 19th century. Bison leather was in high demand — it was used by the government to make Army boots, and bison-leather belts powered the machines that created the industrial revolution. The leftover bones were shipped east by the new railroads in massive amounts to be made into china. The demise of bison led to forced land cessions by Native people as many tribes lost their food supply and trusted the treaties' false promises of food and supplies.

Stackpole & Brother [manufacturer]

Surveyor’s transit, serial number 1332

New York, 1872. Gift of Cornell University School of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

Buff & Buff Manufacturing Co. [manufacturer]

Surveyor’s Level

Boston. Gift of Cornell University School of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

Surveyor’s instruments, rather than guns, were possibly the most influential weapons used in the European conquest and colonization of the American landscape. These tools were used to establish administrative boundaries, delineate property lines, lay out towns, determine transportation routes, and map topography. This transit, which measures horizontal angles to a highly precise degree of accuracy, was used in the engineering school at Cornell University, New York’s “land grant” college established under the terms of the 1862 Morrill Act, which granted federal land to each state to establish agricultural and scientific universities. Surveying was a practical course for the civil engineers who would go on to map the nation and build its infrastructure.

William H. Brewer (1828-1910)

"Map Showing in Five Degrees of Density the Distribution of Woodland within the Territory of the United States, 1873." in Statistical Atlas of the United States …

Washington, D.C., 1874. Printed map, 22 x 33 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

Reflecting growing concerns for the nation’s diminishing natural resources as a result of individual ownership and overconsumption during the first half of the 19th century, this statistical map depicts forest density at the time of the 1870 census. The most extensive woodlands were in the East, along the northern Pacific Coast, and in the northern Rocky Mountains. Outside these forested areas were the grasslands of the Great Plains and the semi-arid scrub lands of the Southwest. Much of the East, which was originally very heavily forested, had less than 20-35 percent of the acreage in woodland after extensive deforestation.

Thomas Hill (1829-1908)

Yosemite Valley

Boston: Louis Prang and Co., 1861-1897. Chromolithograph. Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Print Department. Reproduction 2019.

This chromolithographic print of Yosemite Valley not only provides an example of the remaining forests found in the Rocky and Pacific Coast mountains, but it also captures the drama of Western landscapes. Light shines onto a fertile valley framed by sheer mountain cliffs accentuated by a waterfall. Louis Prang, who immigrated to Boston from Prussia, published such popular, colorful prints, which reinforced the idea that the West was a largely uninhabited, wild, unique landscape.

Negro Troopers of 1899 [Buffalo Soldiers] [24th Infantry].

Film, 5 x 7 inches. Courtesy of U.S. National Park Service. Reproduction 2019.

At the end of the Civil War, black troops enlisted into U.S. forces, both former Union soldiers and new recruits. Known as buffalo soldiers and consolidated into two cavalry and two infantry regiments, these men fought against Native people and the Mexican resistance as they provided security to settlers moving westward. They also participated in the U.S. war against Spain in Cuba and against Spain and the Filipino resistance in the Philippines. Starting in 1899, soldiers of the 9th Cavalry and 24th Infantry spent summers as the first park rangers in two of the nation’s earliest national parks, Yosemite and Sequoia.

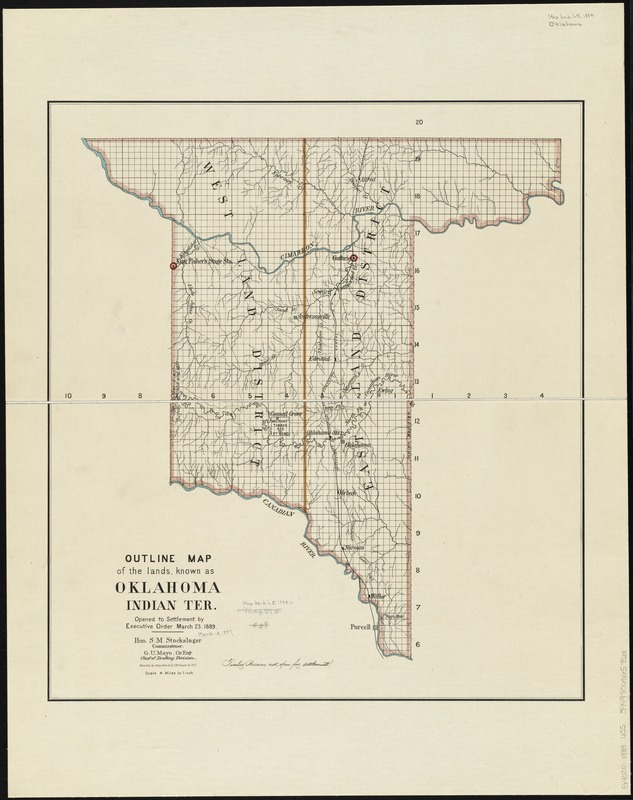

U.S. General Land Office

Outline Map of the Lands Known as Oklahoma, Indian Ter., Opened to Settlement …

Washington, D.C., 1889. Printed map, 24 x 21.5 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 allocated the eastern portion of today’s Oklahoma for the Chahta (Choctaw), Chikasha (Chickasaw), Mvskoke (Creek), Semvnole (Seminole), and Tsalagi (Cherokee) and other eastern tribal nations. Following the Civil War, the U.S. government assigned much of western Oklahoma to tribes living on the Great Plains and further west. When President Benjamin Harrison took office in 1889, he signed a proclamation opening 1.9 million acres of "Indian territory" to non-Natives for homesteading. This map depicts the territory made available for settlement on April 22, 1889. That day, over 50,000 people raced to claim the best lands, including lots in the emerging towns of Guthrie and Oklahoma City.

Land Rush of 1889 and Guthrie, Oklahoma Ave., May 10-89

1889. Photographic prints. Courtesy of Oklahoma Historical Society. Reproductions 2019.

Two photographs illustrate Americans’ eagerness to participate in this land rush. The first records the mass (and blur) of people riding horses and driving wagons to stake their claims. They quickly constructed towns and buildings to meet the terms of the Homestead Act, which required settlers to erect permanent dwellings. The other photograph illustrates the growth of Guthrie, depicting Oklahoma Avenue after only three weeks. Guthrie served as the local land office, and in 1890 it was designated the territorial capital. Three years after Oklahoma’s statehood in 1907, the government moved the capital to Oklahoma City, a growing area at the juncture of major railroads and home to a burgeoning meatpacking industry.

U.S. General Land Office

Map of the United States and Territories … Showing the Extent of Public Surveys …

Washington, D.C., 1890. Printed map, 67 x 80 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center. Reproduction 2019.

This map highlights the federal government’s impact on transforming the American landscape by the end of the 19th century. Designed primarily to show the extent of township surveys, it uses a black grid pattern to represent lands that had been surveyed and open to settlement, which included all or most of the area in the public land states. The map shows the extent of Indian reservations (solid grey), military reservations (solid pink), and private land claims (pink cross hatch or pink outline). The latter, which represent Spanish land grants adjudicated during the 19th century, are most prevalent in Florida, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado and California.

Viewpoint: As the U.S. government took over territory, it introduced the English concept of "land ownership" to lands that were never governed that way under Native stewardship. U.S. land acquisition literally meant that the land in question went from being perceived as "sustaining life" to "sustaining means or income.” It was a big change and it was harsh on Native people. This dynamic overturned the power structure. Systematically Native peoples' life ways and cultures came under threat. Loss of access to land meant loss of true freedom. This process of dispossession repeats itself over and over, forcing Native peoples to begin adopting a foreign way of life as a matter of survival.

Ward Burnett (1811-1884)

Township no. 25 South, Range no. III West of the 6th Principal Meridian

1861, with later annotations. Manuscript survey plat, 16.5 x 19 inches. Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, RG 49. Reproduction 2019.

The Homestead and Pacific Railroad Acts, both passed in 1862, dramatically changed the process for granting public lands. The former allotted 160 acres to white settlers, as well as freed men and women, who would improve land within five years of selection. The latter authorized construction of the first transcontinental railroad and established the principle of giving alternating sections (640 acres) to railroad companies. For example, this township was surveyed in the late 1850s, but most of the land was not selected until the 1870s. Alternating sections marked with “RR” were granted to a railroad company, while those sections patented through the homesteading process are indicated by an X.

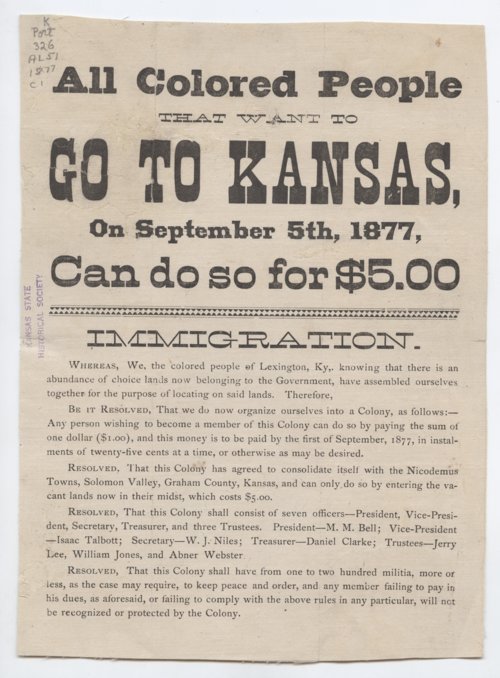

Nicodemus Town Company.

All Colored People that Want to Go to Kansas.

1877. Broadside, 10 x 7.5 inches. Courtesy of kansasmemory.org, Kansas State Historical Society, Copy and Reuse Restrictions Apply. Reproduction 2019.

Following the post-Civil War Reconstruction period, African Americans started to leave the South, migrating to northern cities and Western states and territories. One destination was Kansas, which was promoted in the 1870s through an organized effort known as the Exodus. African American migrants were told they would be moving to a “promised land,” and, as depicted in this broadside, they were enticed with the prospect of obtaining cheap land through the Homestead Act. Unfortunately, by the 1870s, most of the best lands offering good soil and climate had been claimed, and they were forced to settle in more arid parts of the state.

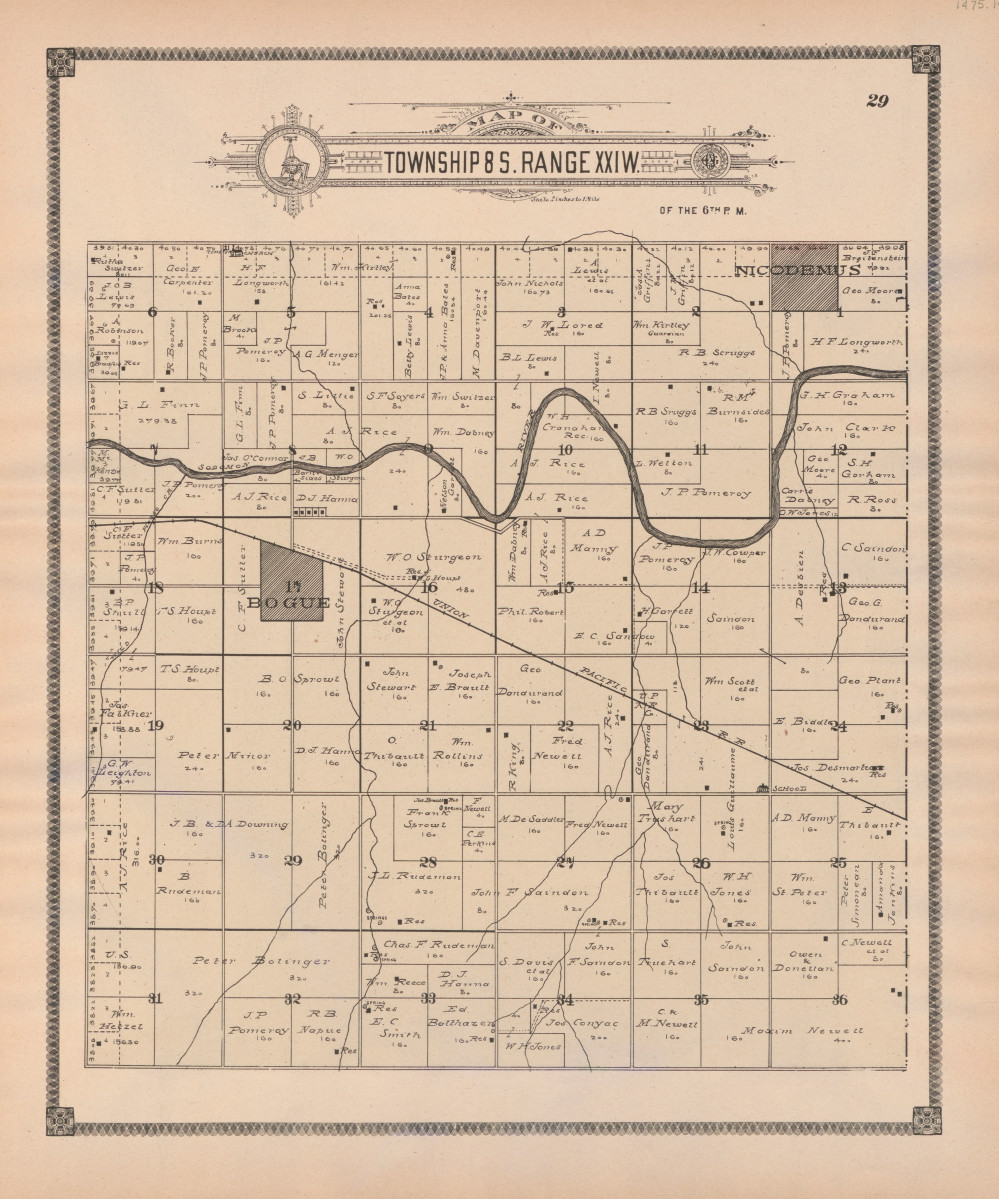

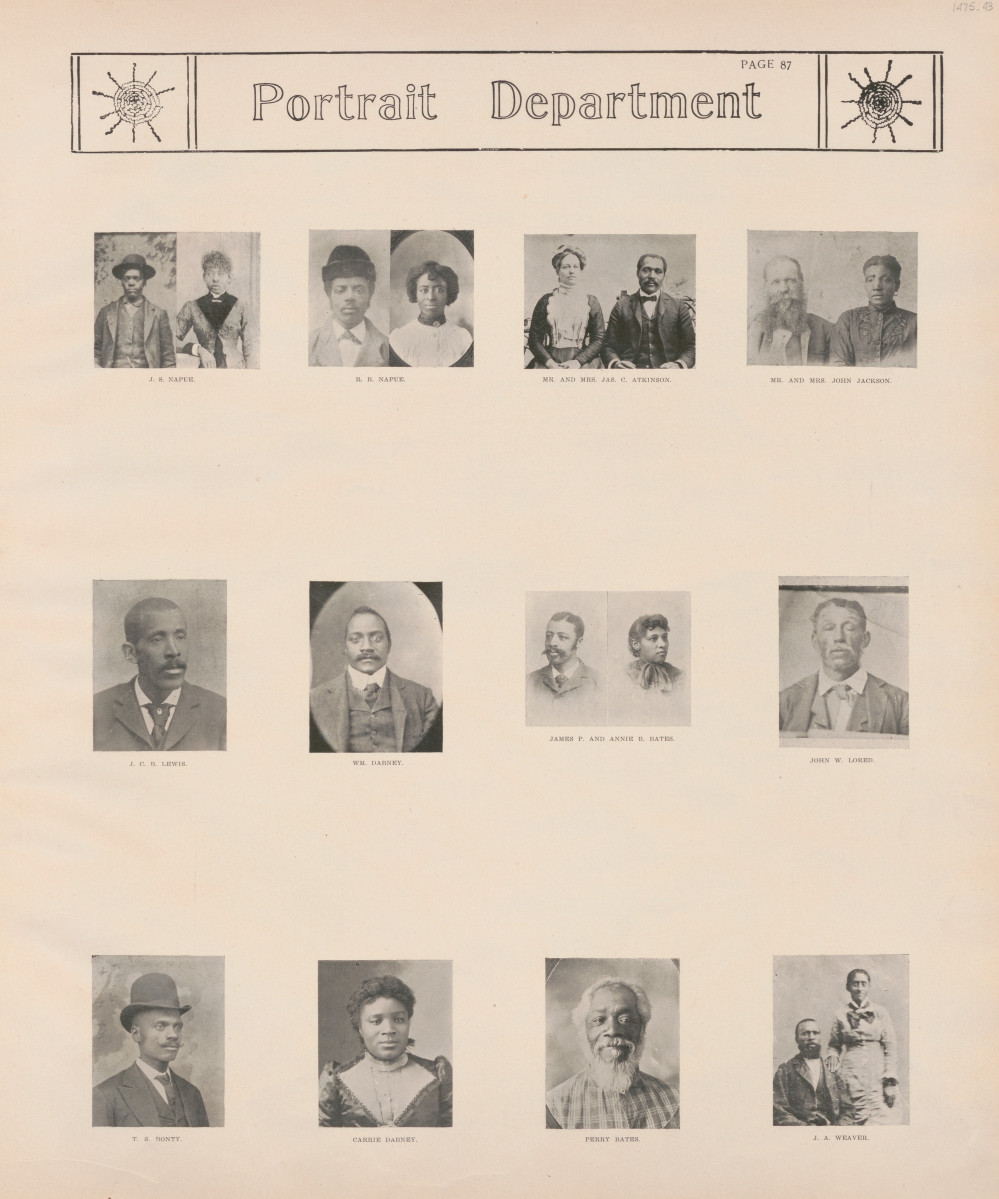

“Township 8 S. Range XXI W.” and “Portrait Department” from George A. Ogle, Standard Atlas of Graham County, Kansas.

Chicago, 1906. Atlas pages, 18 x 15 inches. Courtesy of Library of Congress Geography and Map Division. Reproduction 2019.

One Black town founded during this period was Nicodemus, located on the high plains of western Kansas, as depicted in a county atlas. The town was founded in 1877, growing to 600 by 1880. The town’s efforts to attract the railroad failed, and its population and prosperity were declining by the time this atlas was published. The portrait section, a common feature of county atlases, provides evidence of the African American settlement, since the very last page displays portraits of 12 African American families, six of which can be located on this township map. Others were located in surrounding townships.

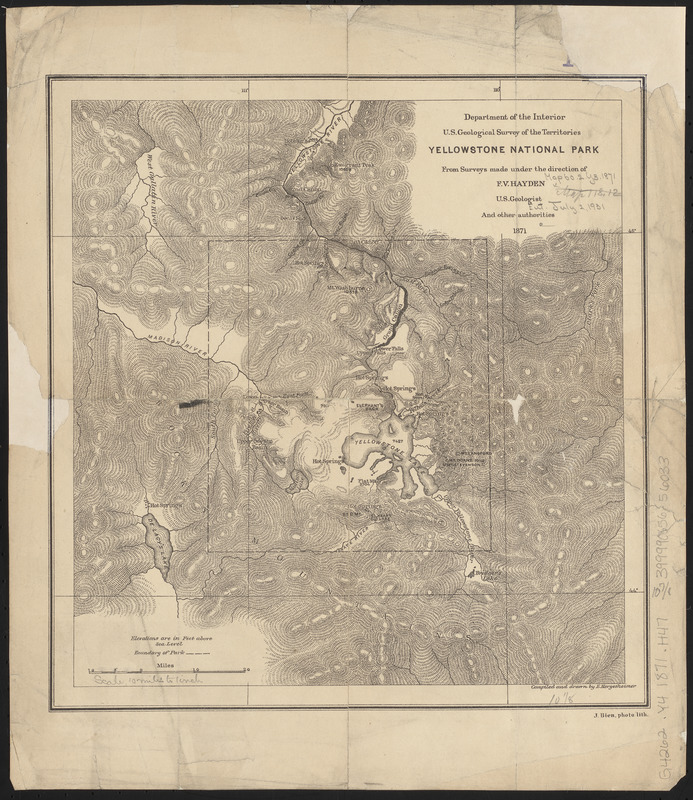

Ferdinand V. Hayden (1829-1887)

Yellowstone National Park

Washington, D.C., 1871. Printed map, 15 x 12.5 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

During the last half of the 19th century, Americans expressed concern about the environmental costs of clearing forests, mining, and flourishing industries. Early conservation advocates sought to preserve the spectacular scenery as well as the land, water, and forests. However, the driving mission of the national parks movement—to preserve natural landscapes untouched by human interference—involved the systemic oppression and removal of Native people. In 1872, Congress designated the headwaters of the Yellowstone River in northwestern Wyoming as the first national park. The pursuit of a pristine wilderness necessitated the forcible removal of the Bannock and Shoshone people from Yellowstone.

Thomas Moran (1837-1926)

The Grand Canyon, Yellowstone

Boston, 1875. Chromolithograph, 9.75 x 14 inches. Courtesy of Boston Public Library, Print Department. Reproduction 2019.

In the mid-19th century, Americans began advocating for landscape conservation out of fear that the West’s beauty would be lost. In 1872, Congress designated Yellowstone as the first national park. Louis Prang’s print of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River, based on a painting by artist Thomas Moran, dramatizes light shining onto waterfalls carved into mountains. Images like this reinforced the misconception that the West was a largely uninhabited and untouched wild environment.

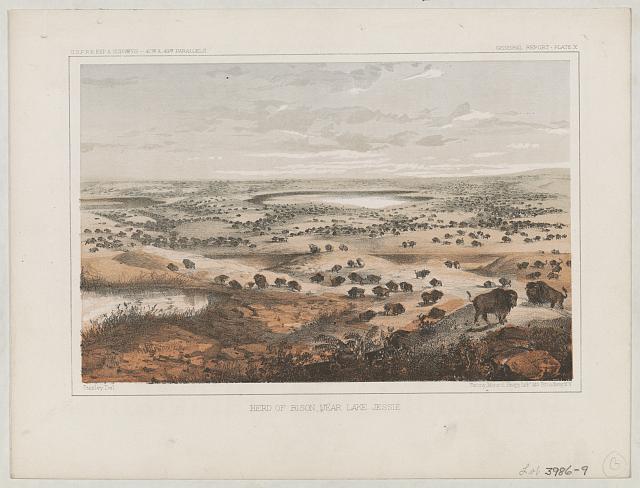

John Mix Stanley (1814-1872)

"Herd of Bison, near Lake Jessie," from Reports of Explorations and Surveys, to Ascertain the Most Practicable and Economical Route for a Railroad …

Washington, D.C., 1855-1860. Lithograph print, 8.5 x 11.5 inches. Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Reproduction 2019.

The abundance of bison still living on the Great Plains at mid-century is documented in this landscape view by John Mix Stanley. It depicts a large herd dotting the North Dakota landscape as far as the eye can see. Stanley, who served as the lead artist for Isaac Stevens’ Northern Pacific Railroad survey in 1853-1854, prepared a variety of views recording scenery, Native peoples, and wildlife which were used for 55 illustrations in the final published report of the railroad survey.

George Catlin (1796-1872)

"Buffalo Hunt, Chase," from Catlin’s North American Indian Portfolio

New York, 1845. Lithograph print, 16 x 22 inches. Courtesy of New York Public Library Rare Book Division. Reproduction 2019.

In contrast, George Catlin’s illustration provides a dramatic, romanticized, Euro-American vision of the West—armed only with spears and bows and arrows, Native people hunt bison on horseback. This rendition evokes excitement of the high-speed chase and the daring of these hunters before such powerful animals. Catlin featured the print in his North American Indian Portfolio. He focused less on detailing an accurate landscape, and more on manufacturing scenes that would appeal to readers.

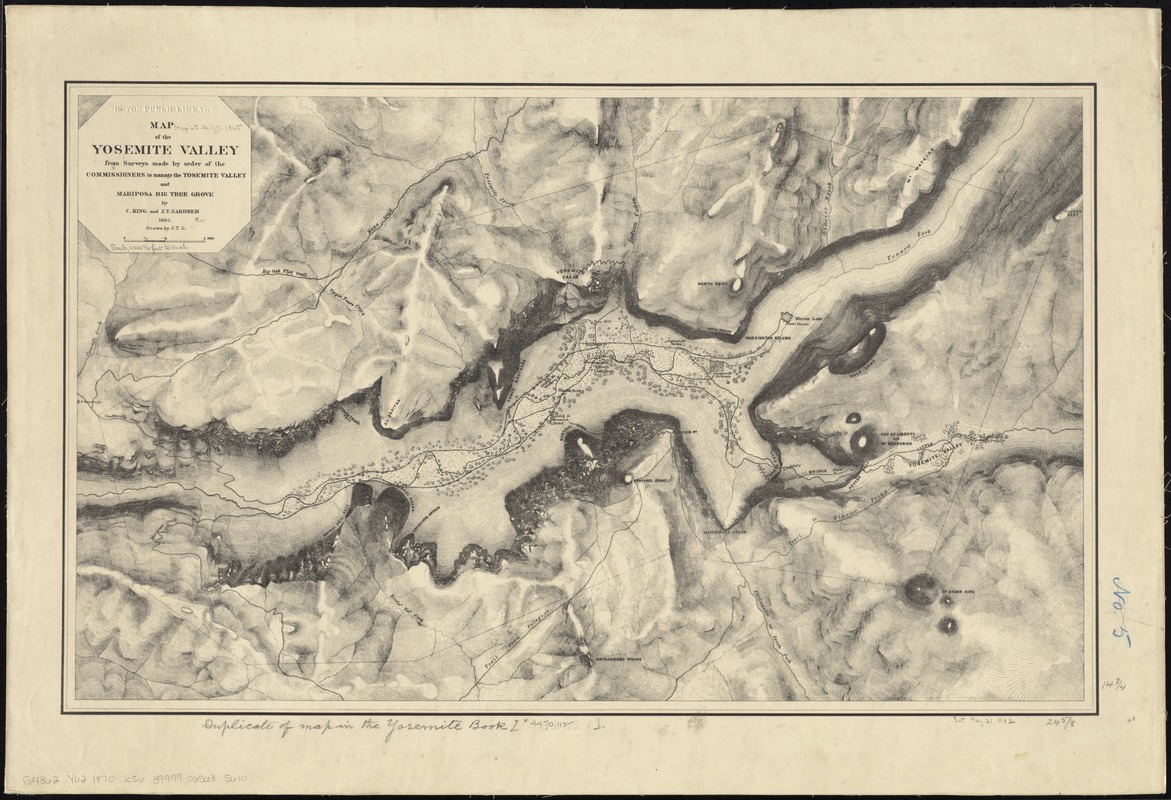

Clarence King (1842-1901) and James T. Gardiner (1842-1912)

Map of the Yosemite Valley …

Washington, D.C., 1870. Printed map, 19.25 x 28 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

In 1890, California's Yosemite Valley became the second national park, although it had already been set aside as a state preserve in 1864, following the violent expulsion of the Ahwahnechee people. Both Yellowstone and Yosemite were mapped as part of four Great Western Surveys that preceded the establishment of the U.S. Geological Survey in 1879. Clarence King, who headed the Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel, mapped Yosemite in 1870, while F. V. Hayden, who led the Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories, mapped Yellowstone in 1871. Both used the traditional method of hachuring—drawing ink strokes along sloped land—to depict the rugged terrain of these unusual landscapes.

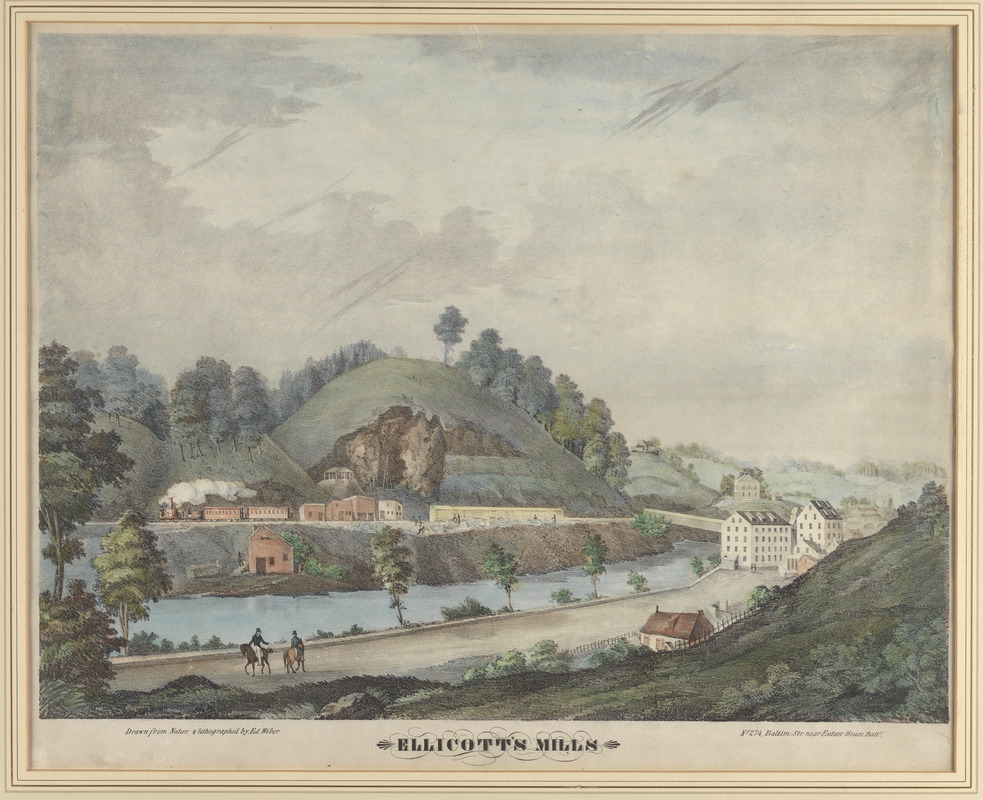

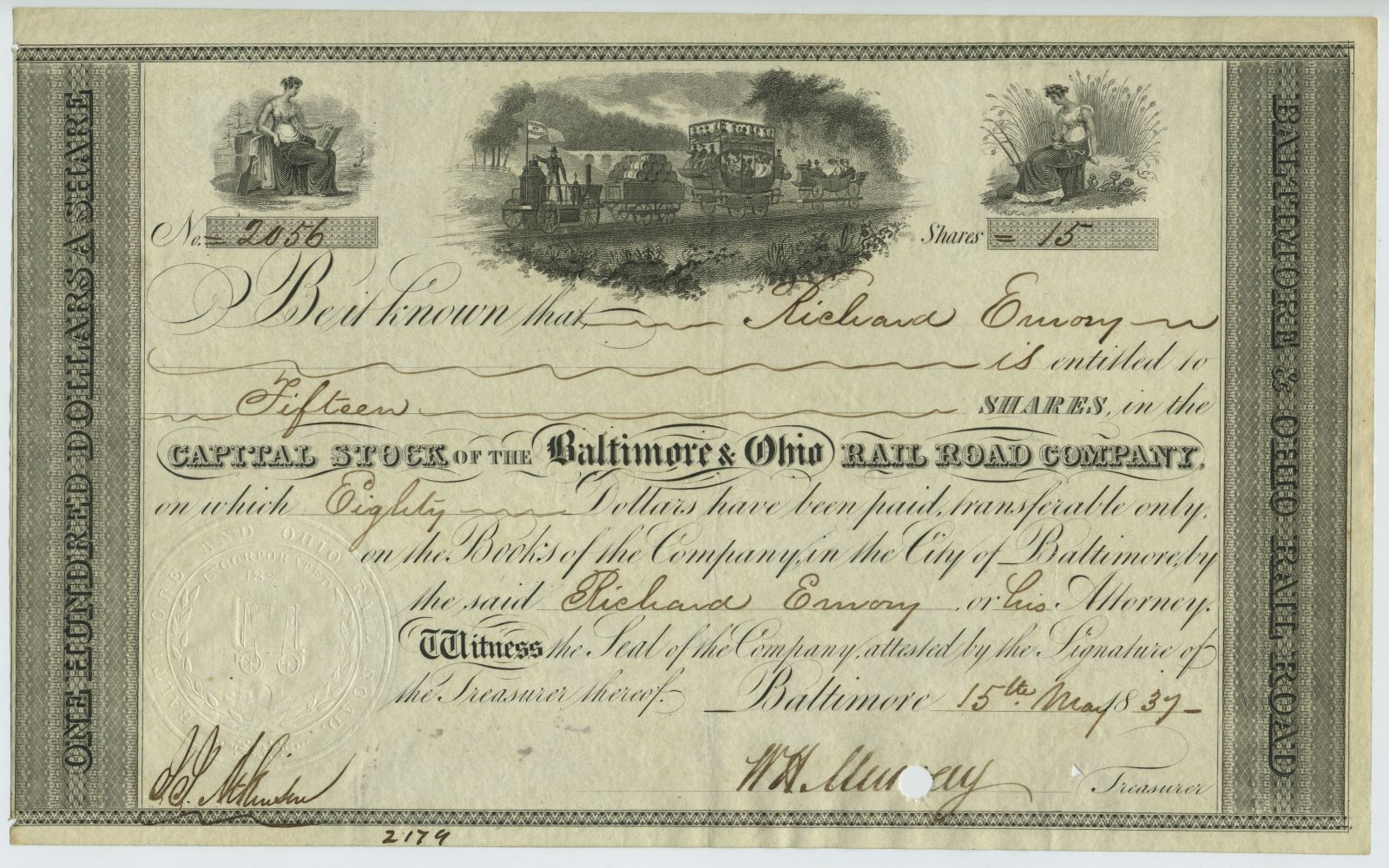

2a. ECONOMY 1800-1862: Transforming the Landscape through Agriculture, Mining, and Industry

While many Euro-Americans believed they were settlers in an untouched wilderness, Native people had altered the landscape by managing forests, growing crops, hunting, igniting seasonal burnings, and building communities for millennia. As U.S. government officials explored, mapped and inventoried the lands west of the Appalachians, they advertised the fertility of the soil and the presence of mineral resources. American settlers cleared the forests to create farms and scarred the earth to mine for resources, which eventually drove the construction of industrial towns and cities.

Timber and coal fueled new factories in urban centers that processed agricultural and mineral products into marketable items. Under colonial and U.S. rule of law, this change was known legally as “improving” the land. Wealth generated from resource extraction and the labor of enslaved and free workers enriched the prospects of a small but very rich upper class, though new industrial jobs and small subsistence farms did lift some free laborers and farmers out of poverty.

VIEWPOINT: When looking at these maps, it's important to keep in mind that the idea of 'improving' land is an English colonial concept. Native people worked the land prior to American settlement. Disease-ravaged native populations and vast farmlands quickly returned to forest. The existing forests were managed systematically by Native peoples in different ways and for different reasons. The law said "improve", but what it meant literally was doing something to make a profit. This was usually done through farming, cutting down trees, planting crops, raising cows, chickens and pigs, and never moving. The concept that this behavior is an "improvement" is purely a European perspective.

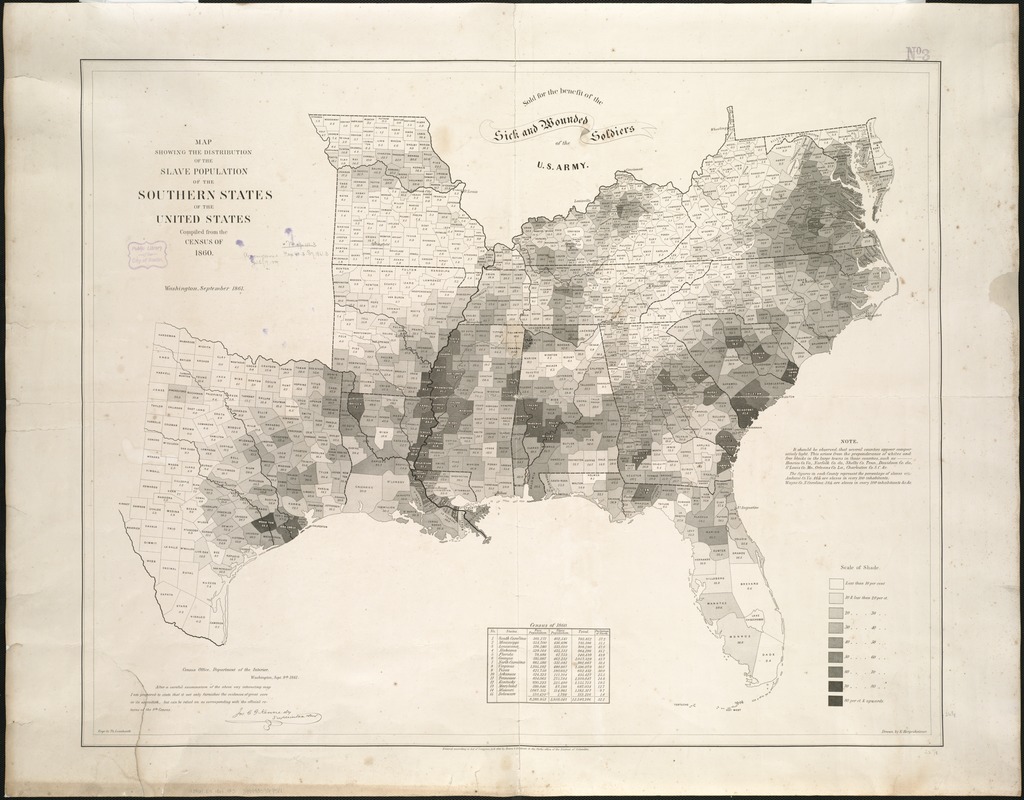

Frederick Law Olmsted (1822–1903)

“A Map of the Cotton Kingdom and its Dependencies in America,” in “The Cotton Kingdom”

New York, 1861. Printed map, 11 x 17 inches. Courtesy of Boston Public Library, Rare Books Department. Reproduction, 2019.

This statistical map addresses the importance of cotton agriculture in the economy before the American Civil War. It represents agricultural productivity rather than distribution and density of cotton cultivation by mapping two variables: productivity of cotton per enslaved laborer (blue, yellow, or red) and ratio of enslaved people to freemen (solid versus dashed horizontal lines). The map accompanied landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted’s published account of his travels through the South during the 1850s. Hired by the “New York Times” as a journalist to report his observations about the region’s economy, he argued that chattel slavery was inefficient for cotton production.

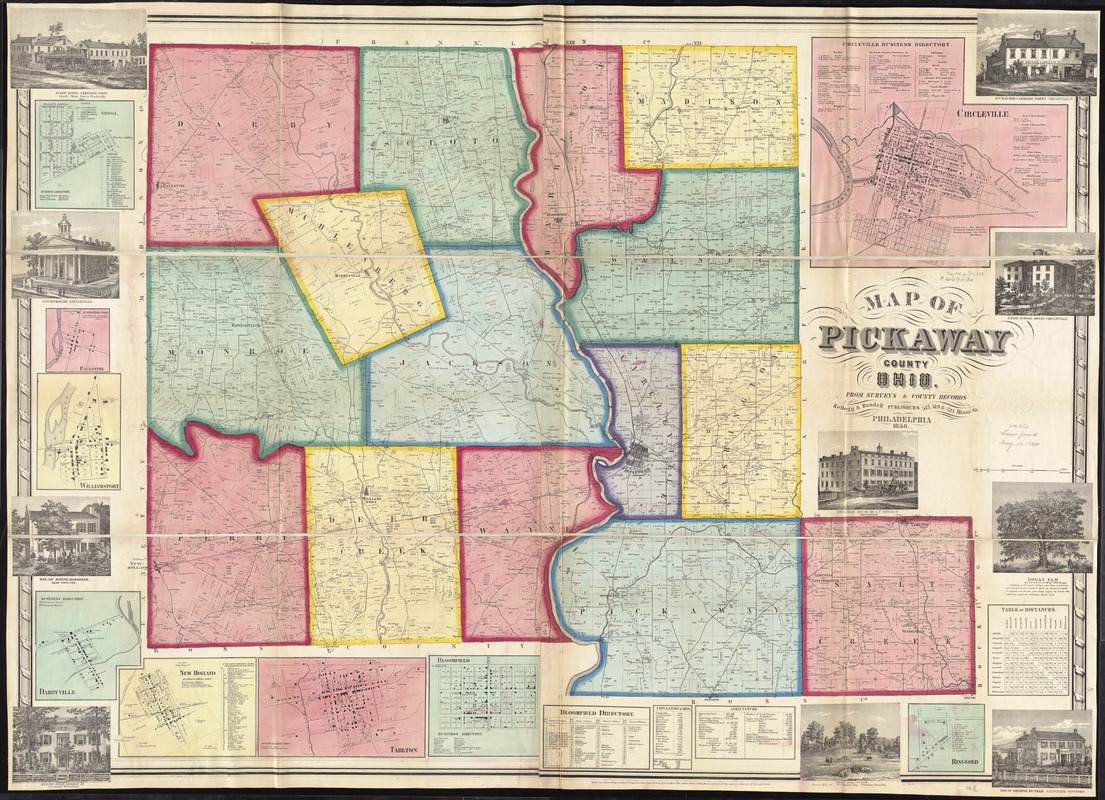

Robert Pearsall Smith (1827–1898)

“Map of Pickaway County, Ohio, from Surveys and County Records”

Philadelphia, 1858. Printed map, 38 x 53 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

Pickaway County, located in central Ohio about 25 miles south of Columbus, provides a good example of a rural Midwestern county where the economy was based on diversified agriculture during the first half of 19th century. The statistical tables along the bottom margin of this land ownership map indicate that the county had a population of 21,000 and farms were valued at $6 million. Agricultural production included a variety of livestock (horses, cows, oxen, sheep, and swine) and crops (corn, wheat, rye, oats, hay, and potatoes). The map also displays the boundaries of individual landholdings, indicating that most were small farms containing several hundred acres.

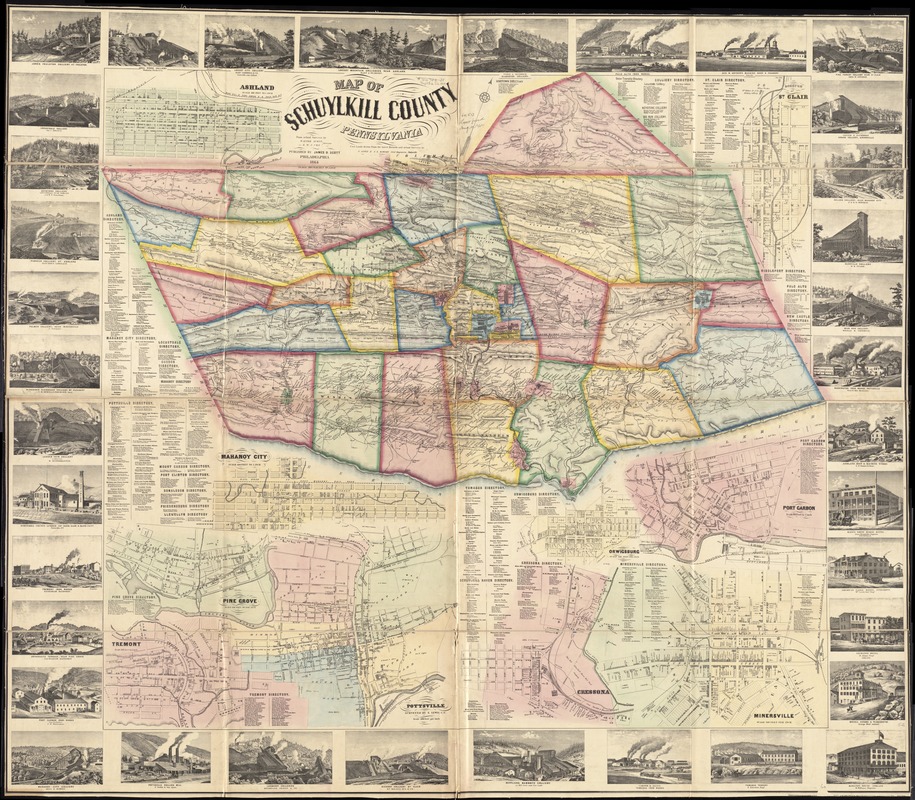

James D. Scott (fl. 1854–1889)

“Map of Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania”

Philadelphia, 1864. Printed map, 45 x 50 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

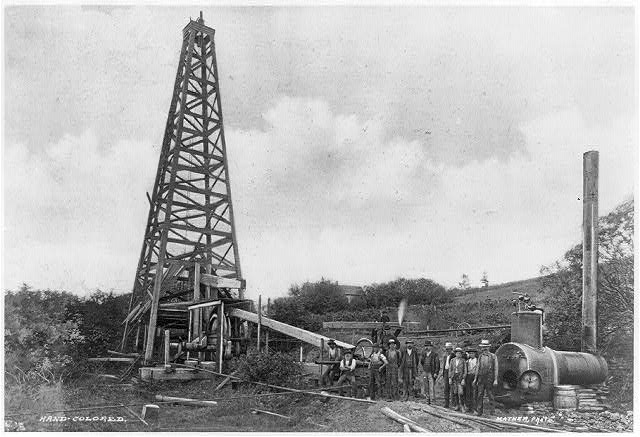

The economy of Schuylkill County, located in northeastern Pennsylvania, focused on anthracite coal mining during the 19th century. This county map documents how that activity dominated the landscape. Of the 37 marginal vignettes, 20 illustrate collieries – coal mines and connected buildings. An additional ten depict local iron manufacturers, fueled by the region’s coal. Also evident is the network of railroads and canals that shipped these resources to New York City and Philadelphia. The map identifies landowners’ names including many coal companies, and also displays street plans and directories for 23 towns, detailing retail activities and service industries within each.

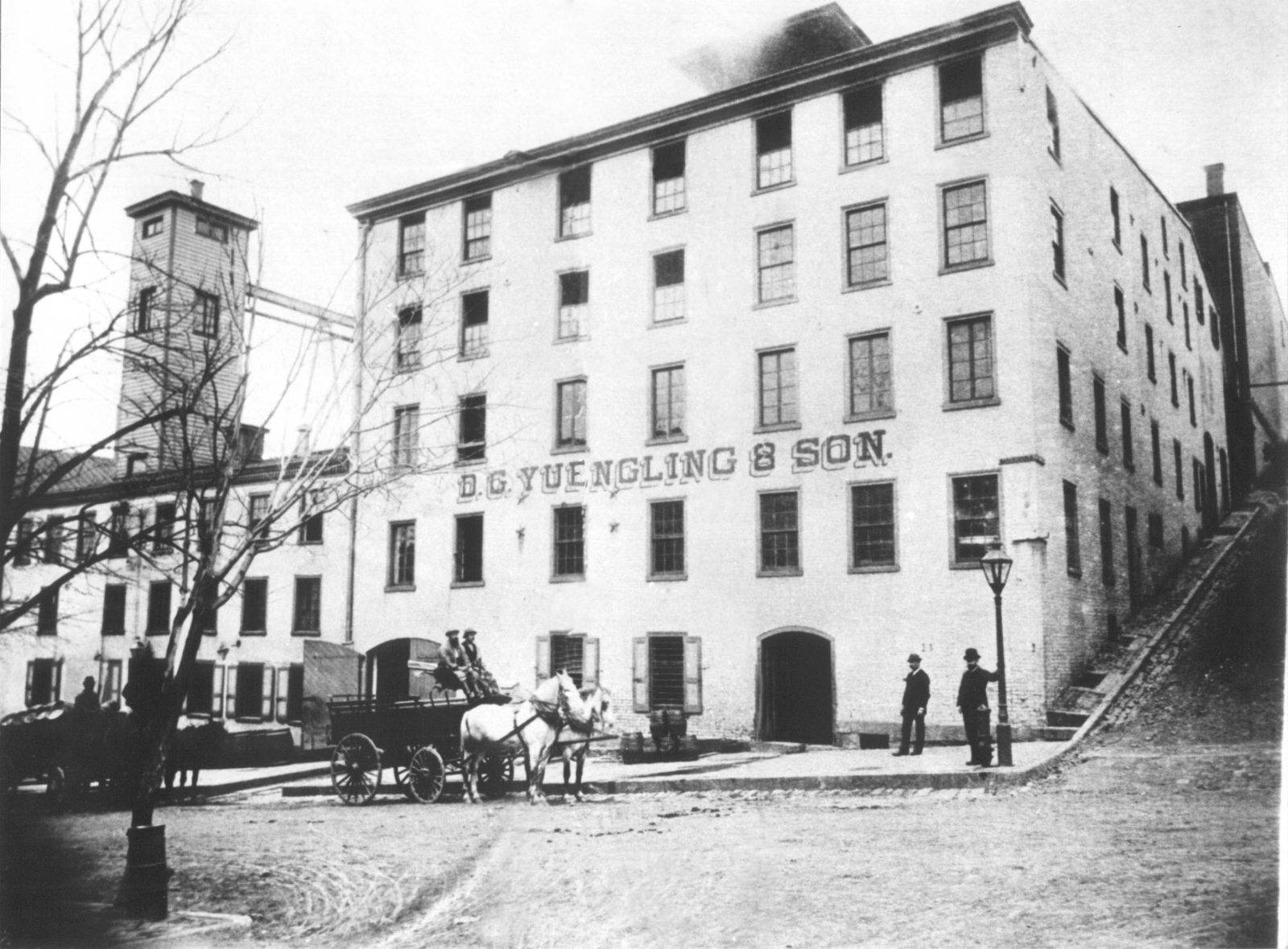

“Exterior View of D.G. Yuengling & Son Brewery”

Ca. 1855. Photographic print, 8 x 11 inches. Courtesy of D.G. Yuengling & Son, Inc. Reproduction, 2019.

The street map for Pottsville, the county seat and largest town, accompanies a directory with 110 listings. Yuengling brewery, which is the oldest brewery in the United States still in operation today, appears in the list and is located on the town map. This photograph, taken around 1855, is the earliest known image of the brewery. David G. Jüngling, who immigrated from Germany, founded the brewery in 1829. He changed the spelling of his name to Yuengling so that Americans could pronounce it. He anticipated that locals—especially the many German immigrants who lived in the region—would purchase his product.

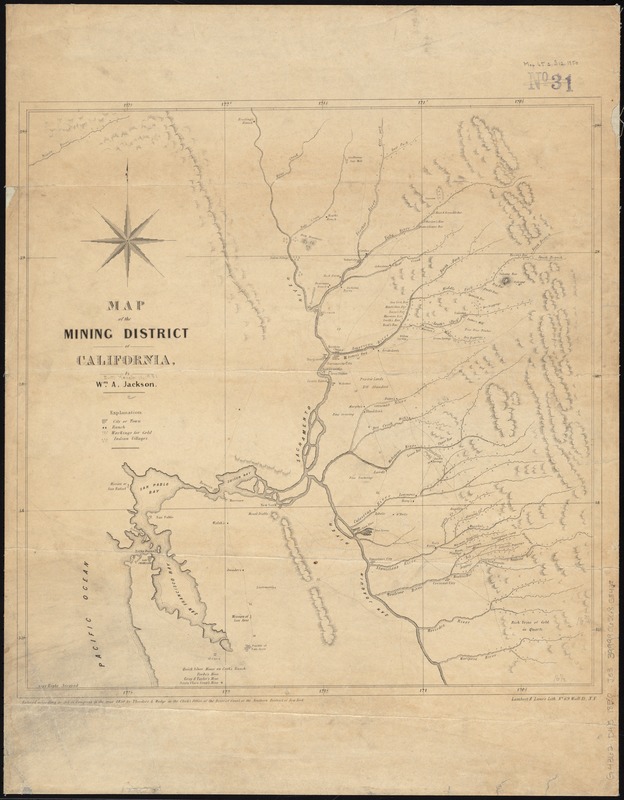

William A. Jackson (fl. 1850)

“Map of the Mining District of California”

New York, 1850. Printed map, 17 x 17 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

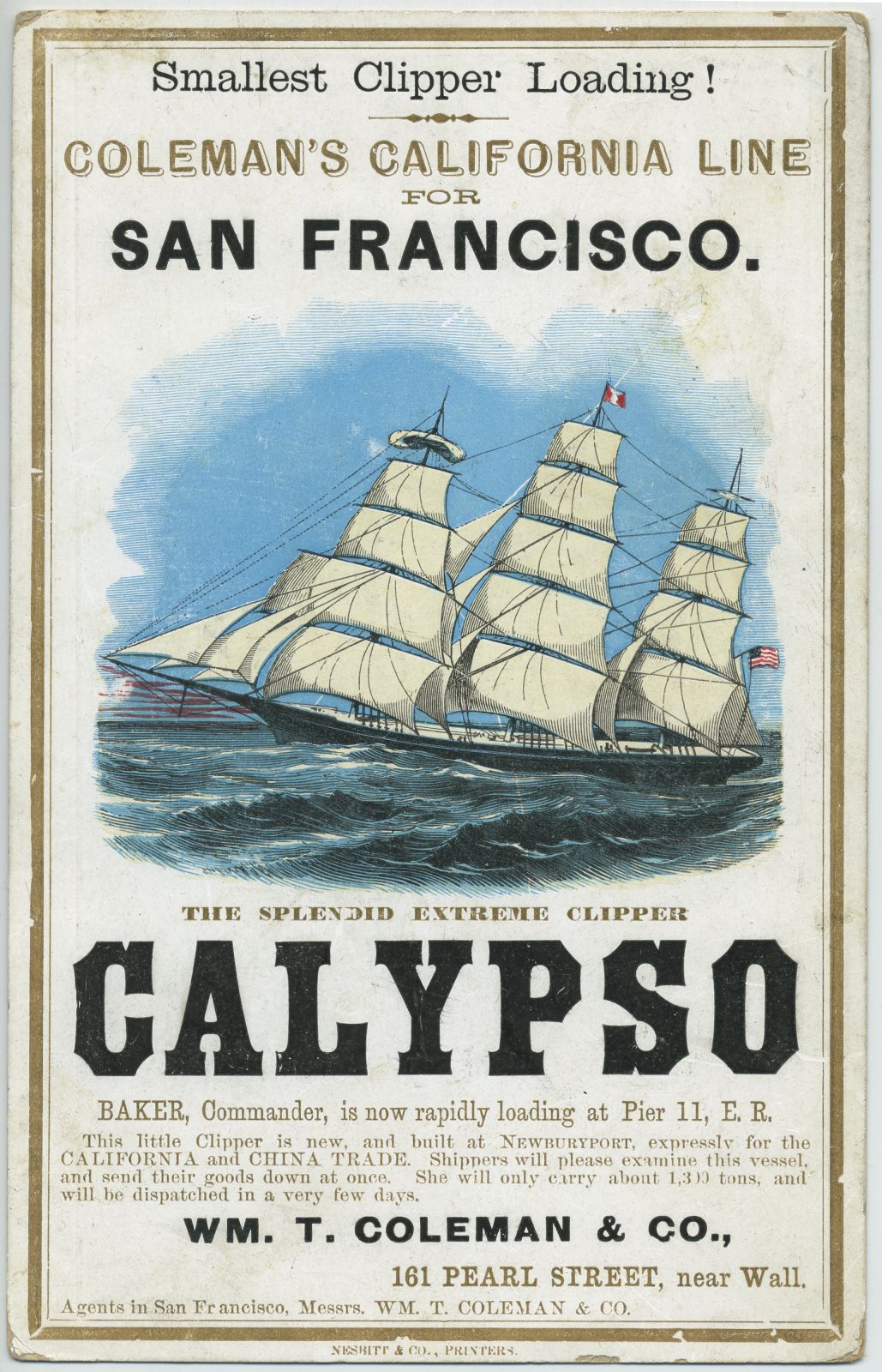

Immediately prior to the discovery of gold in 1848, central California was home to Native communities; Mexican missions, ranchos, and pueblos; the small presidio—fortified military settlement—of San Francisco; and a few white American residents. Published two years later, this map testifies to the frantic pace of settlement during the California Gold Rush. By 1855, over 300,000 immigrants from the eastern United States, Europe, Latin America, Australia, and China established mining camps, towns, and roads. San Francisco grew rapidly. By the 1870s, California’s Native population plummeted from an estimated 150,000 to 30,000. Thousands were forcibly removed from their homelands, enslaved, or killed. Early legislation in California made it lucrative to enslave Native peoples, or to be paid for exterminating them.

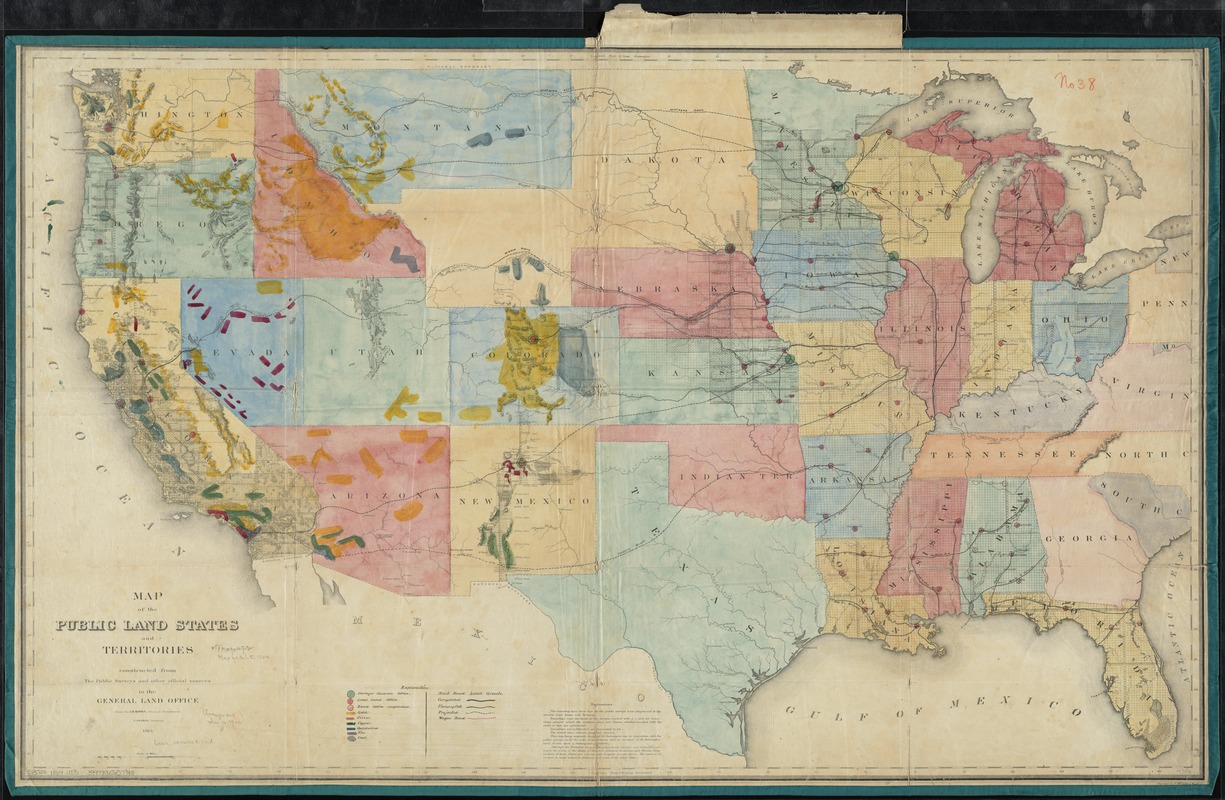

U.S. General Land Office

“Map of the Public Land States and Territories …”

Washington, DC, 1864. Printed map, 30 x 44 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

This map, one of the first thematic maps of the United States published by the General Land Office, provided an inventory of the nation’s land and mineral resources. Besides showing the extent of township surveys, it locates local land offices and completed, uncompleted, and projected railroads. In addition, it uses color coding to identify the locations of six mineral resources – gold (yellow), silver (red), copper (green), quicksilver (blue), tin (purple) and coal (gray) – primarily covering extensive areas of the western states and territories. Ignoring the presence of Native peoples in this region, the map suggests that the minerals are readily available for exploitation.

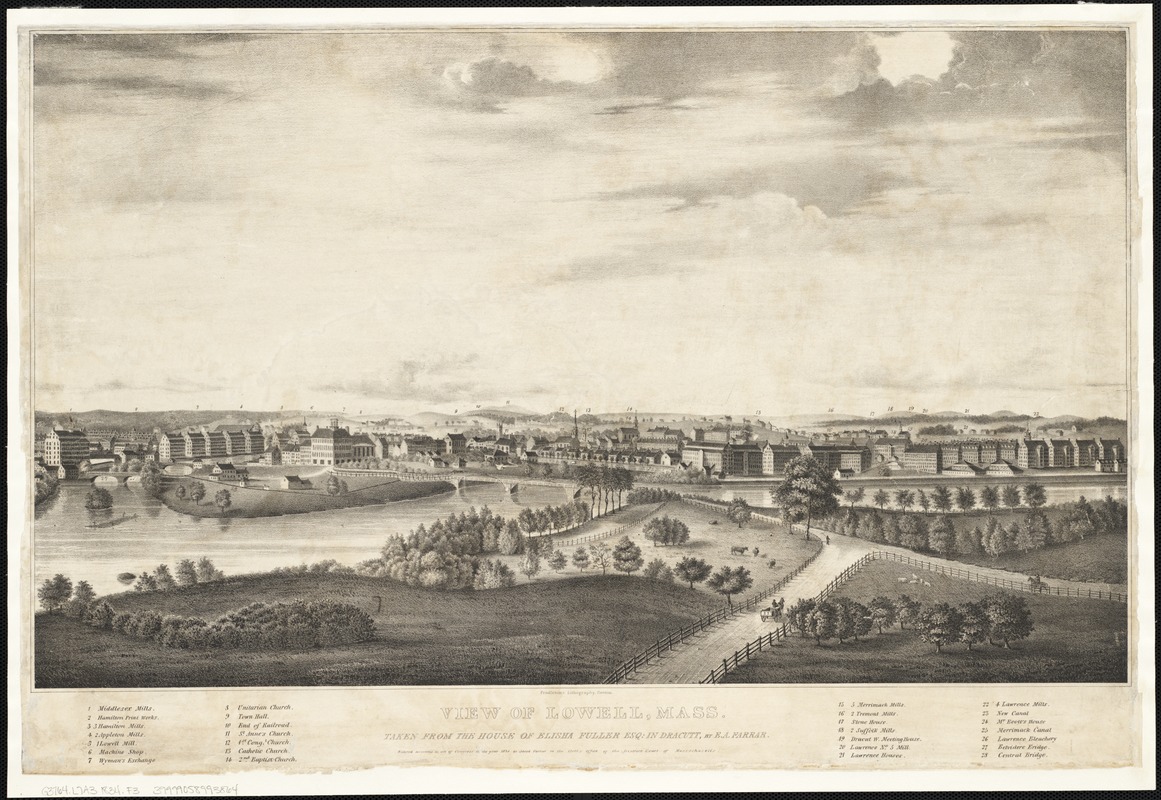

E.A. Farrar (fl. 1834)

“View of Lowell, Mass. …”

Boston, 1834. Printed view, 14.25 x 24 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

Lowell, Massachusetts, the first planned company mill town, is recognized as the cradle of America’s Industrial Revolution. In the 1820s, Boston financiers founded the town when they constructed a textile factory on a canal bypassing the Merrimack River’s Pawtucket Falls. By mid-century, Lowell was the largest industrial complex in the United States. The textile economy relied on cotton grown by enslaved people in the South. The jobs attracted young women from rural New England, and immigrants from French Canada, Germany, and Ireland. The accompanying view, published in 1834, illustrates how the mills dominated the city’s landscape when viewed from the north side of the Merrimack River.

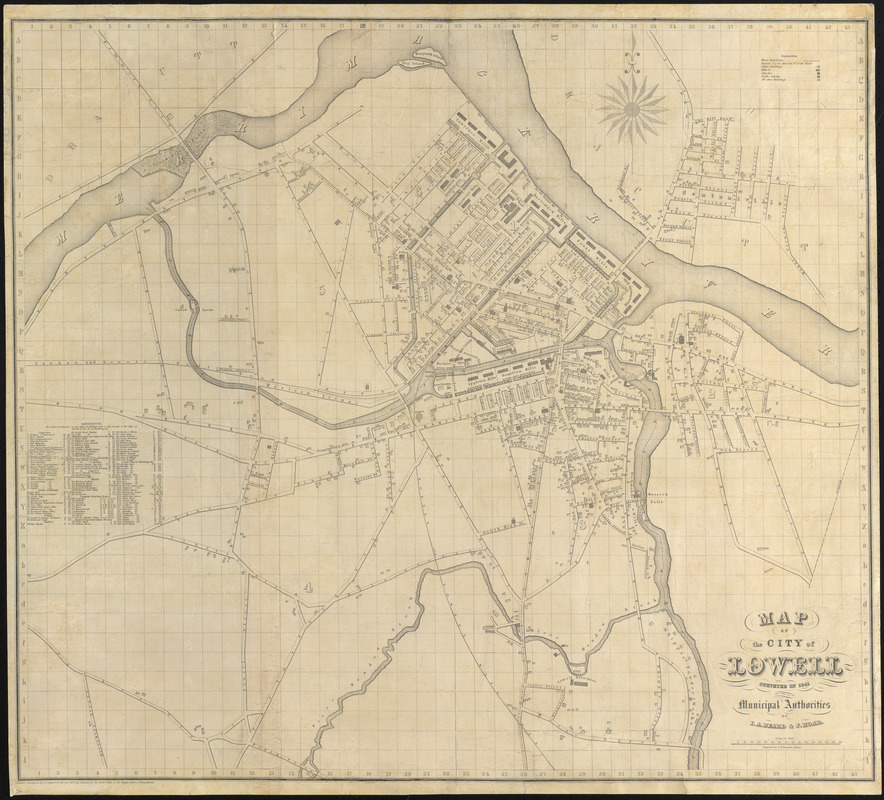

Ithamar A. Beard and J. Hoar

“Map of the City of Lowell Surveyed in 1841 …”

Boston, 1842. Printed map, 30.5 x 34 inches. Courtesy of Lawrence Caldwell.

By the early 1840s, when this map was prepared, Lowell had grown to a population of more than 20,000, making it the state’s second largest city. The map details the footprint and function of individual buildings and demonstrates how dominant the textile industry was in the community. The map notes ten named textile mills as well as an additional 19 mills and factories. Mills were located near the river and canals, which provided waterpower for the factories. The directory lists company boarding houses, agents and superintendent houses, as well as numerous churches, schools, and other public buildings.

Winslow Homer (1836–1910)

“The Bobbin Girl,” from William Cullen Bryant, “Song of the Sower”

New York, 1871. Print. Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society. Reproduction, 2019.

The role of women in the textile industry is reflected in this illustration by Winslow Homer. The same year that the accompanying view was published, the textile workers formed the nation’s first union of working women, “turning out” (striking) in response to proposed wage cuts and blazing a trail for union workers.

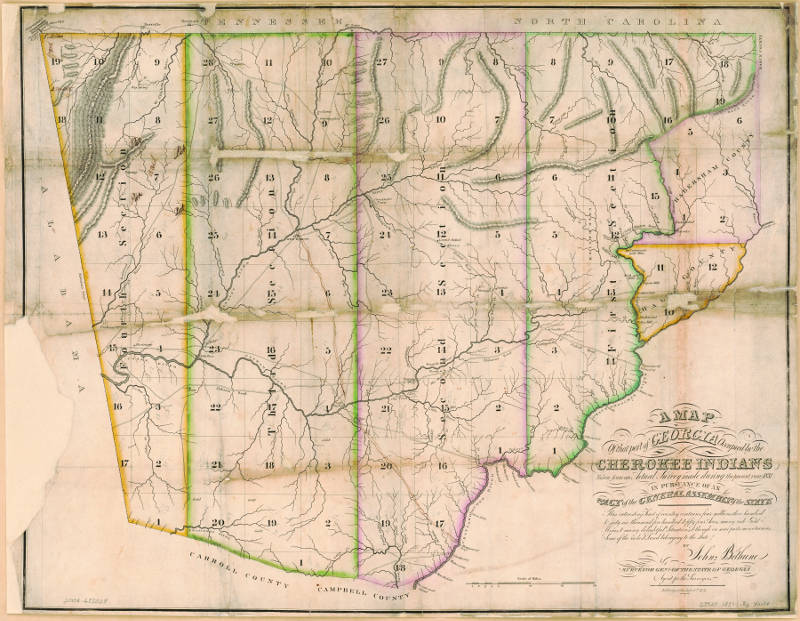

John Bethune (1770–1861)

“A Map of That Part of Georgia Occupied by the Cherokee Indians … “

Milledgeville, GA, 1831. Printed map, 20.5 x 26.5 inches. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division. Reproduction, 2019.

The cultural and economic landscape of northwestern Georgia underwent dramatic changes before the American Civil War. This region formed part of the Tsalagi (Cherokee) homelands until the U.S. government forced the tribe’s removal to the Great Plains from 1836 to 1839. Gold was discovered in 1828, initiating one of the nation's first gold rushes and hastening their expulsion. This map, prepared in 1831 by the Georgia Surveyor General, promoted the richness of the area, especially the gold mines and fertile soil coveted by settlers. Besides locating a number of gold mines, the map also displayed Tsalagi communities and roads.

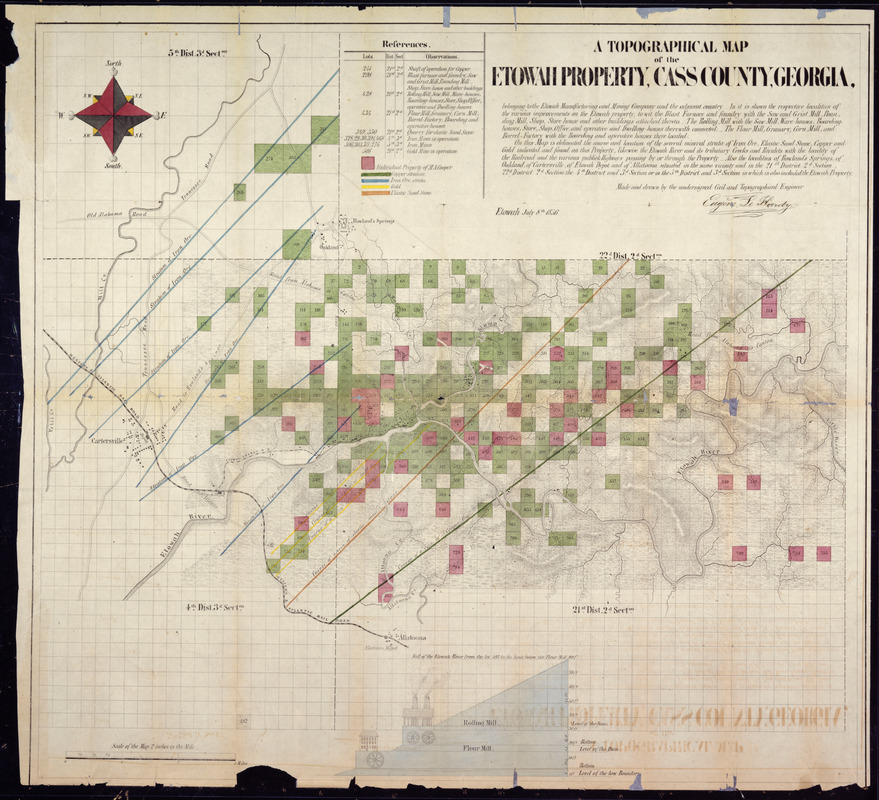

Eugene LeHardy (fl. 1856)

“A Topographic Map of the Etowah Property, Cass County, Georgia”

Etowah, GA, 1856. Film of printed map, 5.5 x 8 inches. Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration. Reproduction, 2019.

Georgia’s gold rush ended by the early 1840s, but the discovery of other mineral resources, including iron, furthered the extensive exploitation of the landscape. During the first half of the 19th century, iron furnaces, which relied on charcoal, tended to be small rural operations located near iron deposits. One example is the Etowah Manufacturing and Mining Company located in northwestern Georgia. The accompanying topographic map shows that the small village encompassed the furnace, rolling mill, and workers’ housing and stores, while the company owned at least 10,000 acres of surrounding forest. This landscape was altered by cutting down massive amounts of timber to produce charcoal.

2b. ECONOMY 1862-1900: Transforming the Landscape through Agriculture, Mining and Industry

While many Euro-Americans believed they were settlers in an untouched wilderness, Native people had altered the landscape by managing forests, growing crops, hunting, igniting seasonal burnings, and building communities for millennia. Different Native peoples developed relations with Spanish, French, Dutch, and English colonial powers. In trading partnerships, especially with the French and British, they often hunted animals and finished pelts that reached Europe and Asia as part of a global fur trade.

As U.S. government officials mapped and inventoried the lands west of the Appalachians, they advertised the fertility of the soil and the presence of mineral resources to American settlers who in turn pursued a more intensive exploitation of the landscape. They cleared the forests to create farms and scarred the earth to mine for resources, which eventually drove the construction of modern cities. Timber and coal fueled new factories in urban centers that processed agricultural and mineral products into marketable items. Under colonial and U.S. legal systems, this change was known legally as “improving” the land.

For Kids

Ranchers, farmers, miners, tradespeople, and bankers all contributed to the wealth of the expanding United States and the growth of cities. Another group’s relationship to the economy changed drastically after the Civil War: formerly enslaved people and their descendants. Though not free from racism and discrimination, their embrace of new opportunities changed the country in meaningful ways.

- These maps show how farms, mines, factories and new cities spread across the country. What is not shown?

- What stories do the maps tell about the relationships between people, the environment and money?

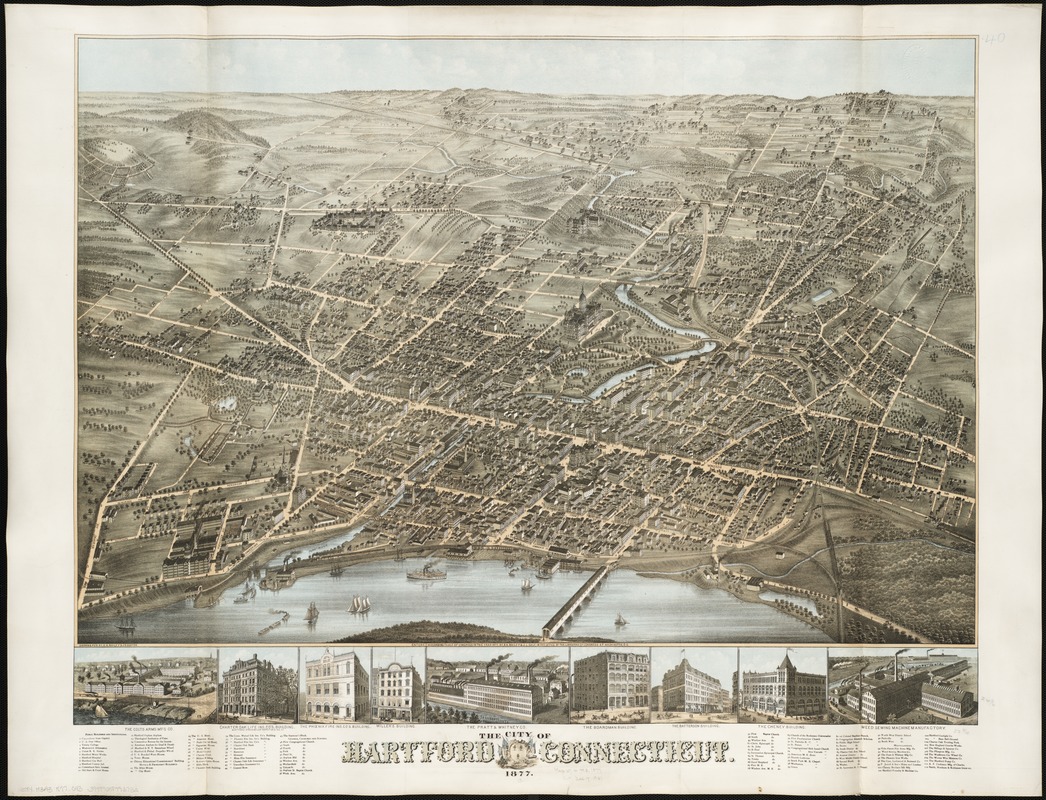

Oakley Hoopes Bailey (1843-1947)

The City of Hartford, Connecticut

Boston, 1877. Printed map, 25 x 33 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

For several decades following the Civil War, Hartford, Connecticut ranked as the richest city in the nation. As the headquarters for numerous insurance companies, it was known as the “insurance capital of the world.” The city also led the Industrial Revolution as a large producer of guns, sewing machines, and machine tools. One marginal inset illustrates the Colt Arms Manufacturing Company, which produced guns widely used during the Civil War and in later conflicts with western tribal nations. This panoramic view from the east captures the city’s economic diversity in the 1870s, when it had reached a population of 40,000.

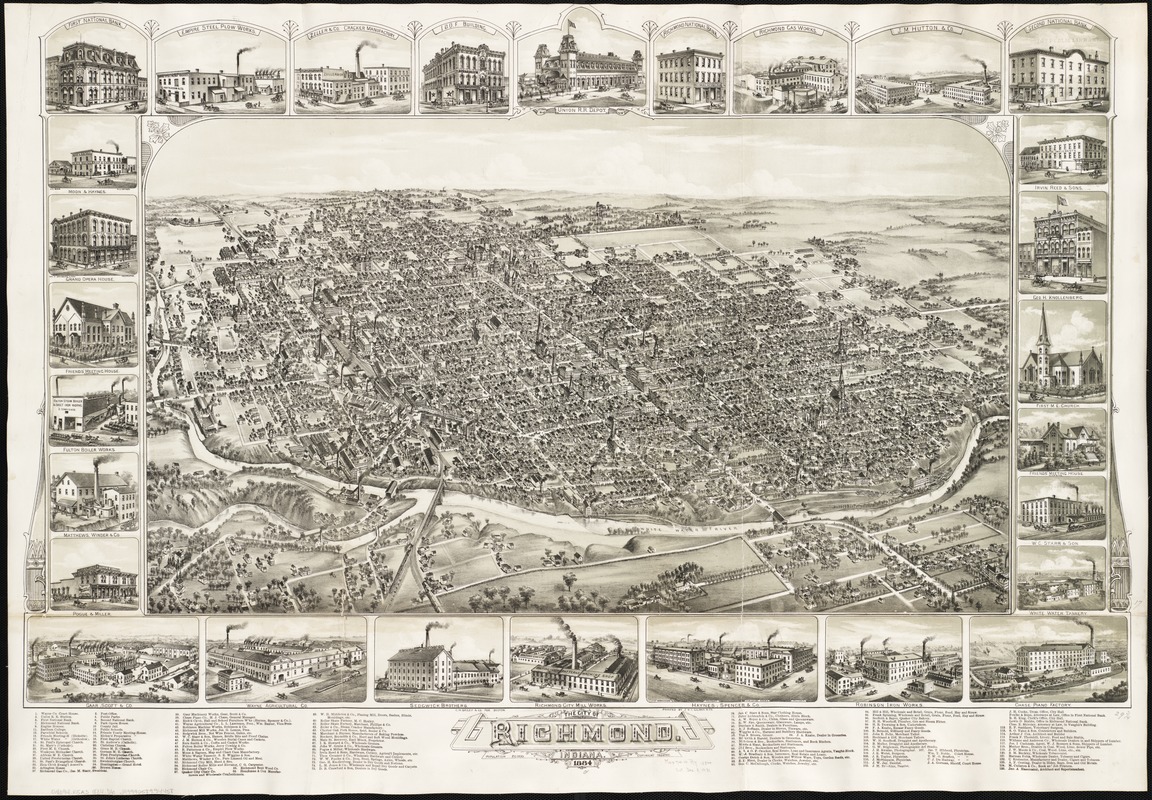

Albert E. Downs (fl. 1880-1916)

The City of Richmond, Indiana

Boston, 1884. Printed map, 24.5 x 37 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

Richmond, Indiana, located on the original National Road near the Indiana-Ohio boundary, provides an example of a midwestern industrial town that was a center of government, commerce, finance, and education. Oriented with east at the top, this bird’s-eye view places the White Water River and the railroad crossing in the foreground. The map’s directory lists 29 industrial enterprises. Many local factories manufactured farm implements and processed agricultural produce. The largest companies produced threshing machines, grain drillers, and mowers, while smaller plants made crackers, baking powder, and linseed oil. Others built non-agricultural goods, such as pianos, caskets, boilers, and even map cases.

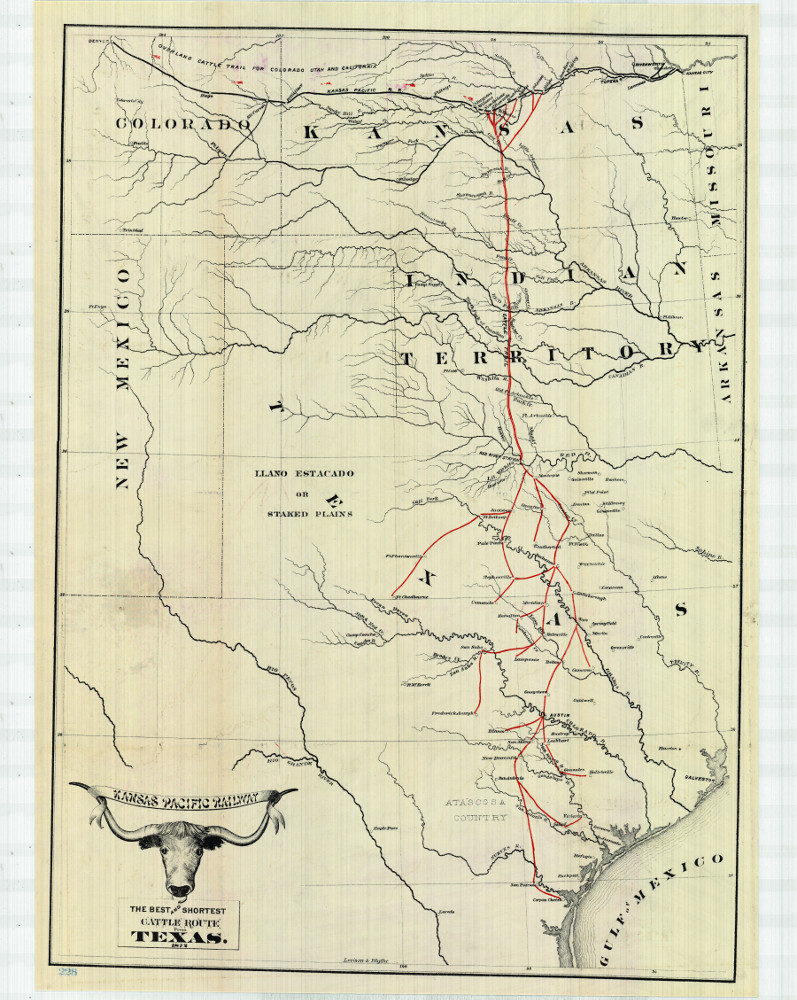

Kansas Pacific Railway

The Best and Shortest Cattle Route from Texas

St. Louis, 1872. Printed map, 20 x 14.5 inches. Courtesy of Library of Congress Geography and Map Division. Reproduction 2019.

Modern fiction, movies, and television depict cattle drives as an iconic image of the American West. In reality, they only occurred from 1868 to 1886. Cowboys drove herds of 2,000 to 3,000 longhorn cattle from Texas ranches north through Indian Territory to Kansas, as illustrated on this map. From Kansas railheads, cattle were shipped east to stockyards and slaughterhouses or west to mining towns and military posts. The route provided sufficient grass, avoided tolls charged by tribal nations, and veered around farms in eastern Kansas, but the routes kept shifting westward to avoid expanding white settlements. The success of the cattle industry hinged upon the removal of Native people and wildlife.

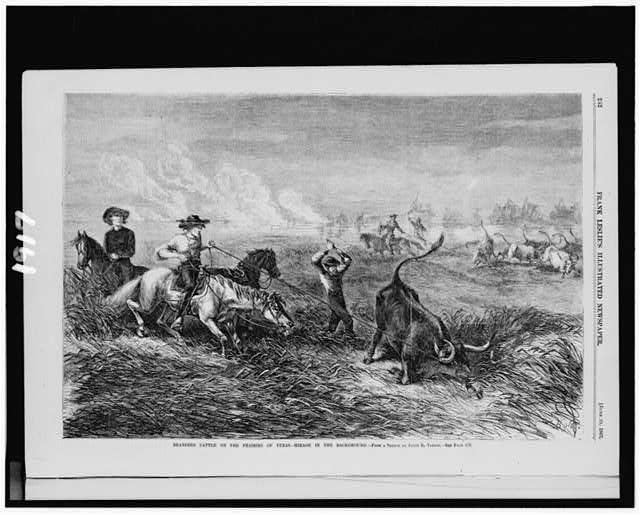

James E. Taylor (1839-1901)

“Branding Cattle on the Prairies of Texas …” from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper

June 29, 1867. Wood engraving, 11 x 16 inches. Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Reproduction 2019.

During the late 19th century, engraved illustrations—like the one seen here—became the first kinds of pictures that could be produced cheaply and quickly. In this engraving, a man riding a horse lassos a furious bull. Another man stands ready with a brand to mark ownership, while cowboys guide groups of cattle in the background. The engraving, and many others like it, exalted the West as a place of excitement, where courageous men could prove themselves by conquering animals and nature.

Erwin E. Smith (1886-1947)

“African-American Cowboys with their Mounts Saddled Up.” 1911/1915, Photograph, 5 x 4 inches. Courtesy of Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas. Reproduction 2019.

The cowboys of popular culture have commonly been portrayed as white Anglo men working on cattle drives in the West. Historians estimate, however, that as many as one in three cowboys were either Mexican or African American in the later half of the 19th century. Many enslaved African Americans in Texas were skilled in tending cattle from their work on ranches. After the Civil War, these formerly enslaved men went on to work as cowboys, one of the few jobs available to them. While they faced discrimination from society at large, many period sources suggest they experienced a degree of relative equality within their cowboy crews.

J. Hale Powers & Co.

Gift for the Grangers

Cincinnati, 1873. Chromolithograph, 21.5 x 17 inches. Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Reproduction 2019.

A colorful poster portrays prosperous farmers to promote the National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry. Founded in 1867, the Grange, advocated for farmers’ political interests, especially against powerful railroad companies and provided an opportunity for farmers—men and women alike—to socialize and learn about agricultural innovations. The central illustration depicts a farmer, shovel in hand, in front of his farm. Smaller images feature a Granger meeting, a harvest dance, and men and women working on their farm. According to this print, the Grangers helped farmers overcome “ignorance” and “sloth” (as represented in the image in the bottom middle) and improve their lives.

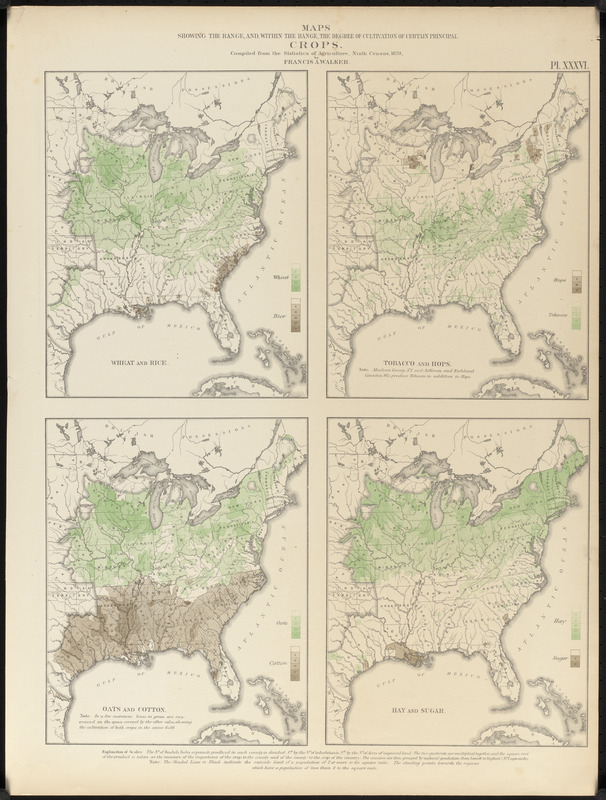

Francis A. Walker (1840-1897)

“Maps Showing the Range … of Certain Principal Crops,” from Statistical Atlas of the United States …

Washington, D.C., 1874. Printed map, 22 x 16.5 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

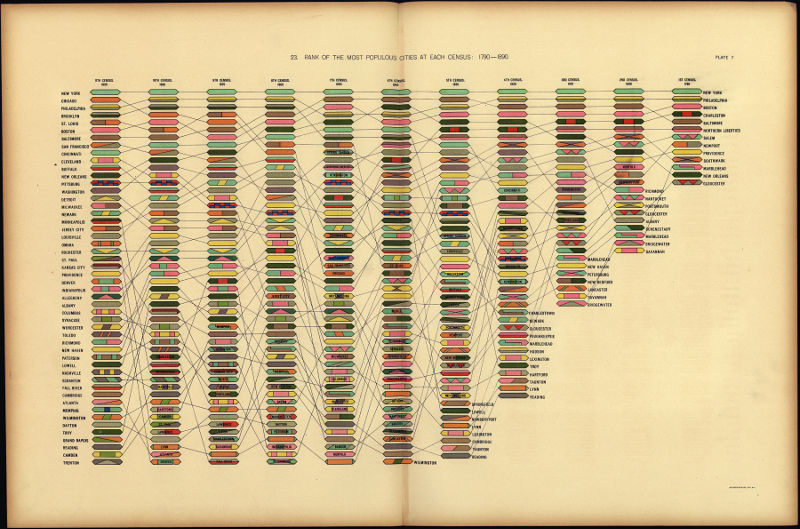

Agricultural production in the eastern United States is represented by this plate from the statistical atlas illustrating the 1870 census. There are four maps, each showing the distribution and degree of cultivation of two major crops. As the first national atlas, this prize-winning volume was a landmark publication displaying an unprecedented number of visual statistics and thematic maps. It was compiled by Francis Amasa Walker, Superintendent of the ninth and tenth censuses (taken in 1870 and 1880) and Commissioner of Indian Affairs (1871-1872). Walker transformed the census, acquiring and tabulating vast quantities of geographic information about the rapidly expanding country. However, this furthered the ability of the federal government to manage and control "the Indian as an obstacle to the national progress," as Walker described Native tribes in 1879.

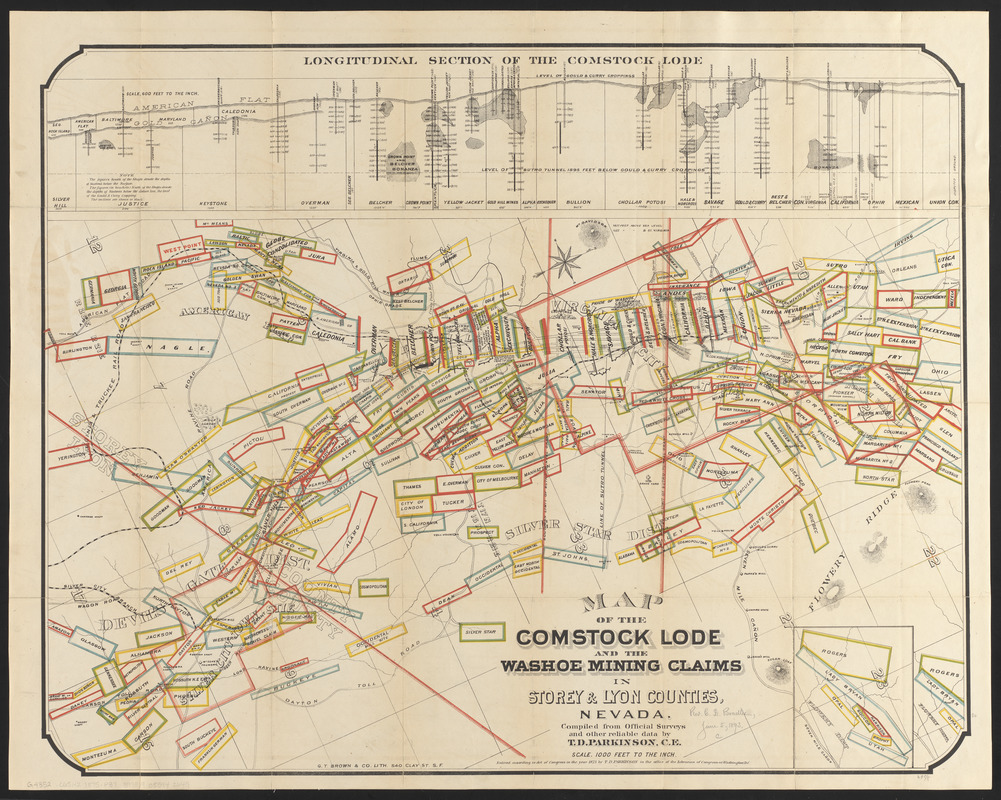

T.D. Parkinson

Map of the Comstock Lode and the Washoe Mining Claims in … Nevada

San Francisco, 1875. Printed map, 25.5 x 32.5 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

In 1859, major deposits of silver known as the Comstock Lode were discovered on the Nevada side of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Mining spurred the rapid growth of Virginia City, which reached a population of 15,000 by 1863, prompting Nevada’s statehood in 1864. This 1875 map delineates the boundaries of the many mineral claims while the cross sections indicate deep shafts to the silver deposits. Large debris piles at each mine’s entrance left a distinctive scar on the landscape.

VIEWPOINT: When the federal government codified place names, they often relied on local input, including derogatory terms which reflected cruel racial attitudes. This practice was especially frequent in mining towns, not because there were large numbers of African Americans, but because the presence of a single one was sufficiently conspicuous to suggest calling a place by a racial epithet. In this map, the offensive term “Nigger Ravine” appears towards the lower left. The name was replaced by “Negro Ravine” by the Board on Geographic Names in 1962. Stewart Udall, Secretary of the Interior at the time, explained why the agency had chosen to remove all instances of the word "Nigger" from federal maps: “I do not see how the Federal Government can in conscience require the use of the word in any connection.”

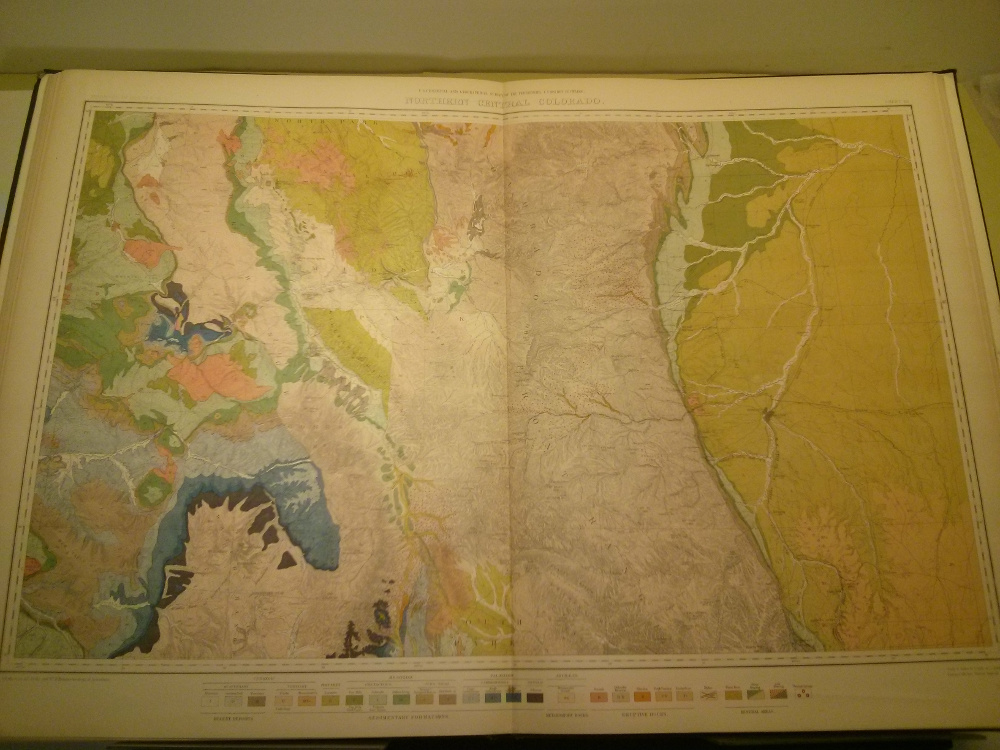

F. V. Hayden (1829–1887) and U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories

“Northern Central Colorado,” in Geological and Geographical Atlas of Colorado and Portions of Adjacent Territory.

[New York], 1877. Atlas plate, 27.5 × 21 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

Scientific expeditions consisting of geologists and cartographers were sent out by the federal government to document the landforms of the western states. The goal was not simply to add to geographic knowledge, but also to identify sources of mineral deposits and promote the development of a mining industry. This 1877 atlas of Colorado shows the bedrock geology in colors corresponding with the age and type of rock, while formations likely to yield silver and gold are identified with dotted patterns. A silver boom in 1879 led to the establishment of quick-build mining towns, while Denver, shown here towards the right center of the map, grew from just over 4,000 people to more than 100,000 between 1870 and 1890. Today, many of Colorado’s mountainous landscapes that were once valuable for mineral extraction are now valuable for a different purpose: outdoor activities like skiing and backpacking.

Edwin Forbes (1839-1895)

Lagonda Agricultural Works, Springfield, Clark County, Ohio

New York, 1859. Chromolithograph, 24 x 30 inches. Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Reproduction 2019.

Many midwestern towns manufactured machinery to help farmers increase their productivity. This colorful image advertises the Lagonda Agricultural Works based in Springfield, Ohio. In the center, three men demonstrate how to use one of the machines. On the left and right, two men stand with manual tools in their hand, yearning for this new technology. The vignettes in the bottom corners showcase additional tools available for purchase. It is no accident that the advertisement portrays these farmers as uniformly white and male. These characteristics embody physical ideals mirroring a national identity that reinforced and benefited from stereotypes of whiteness and western civilization.

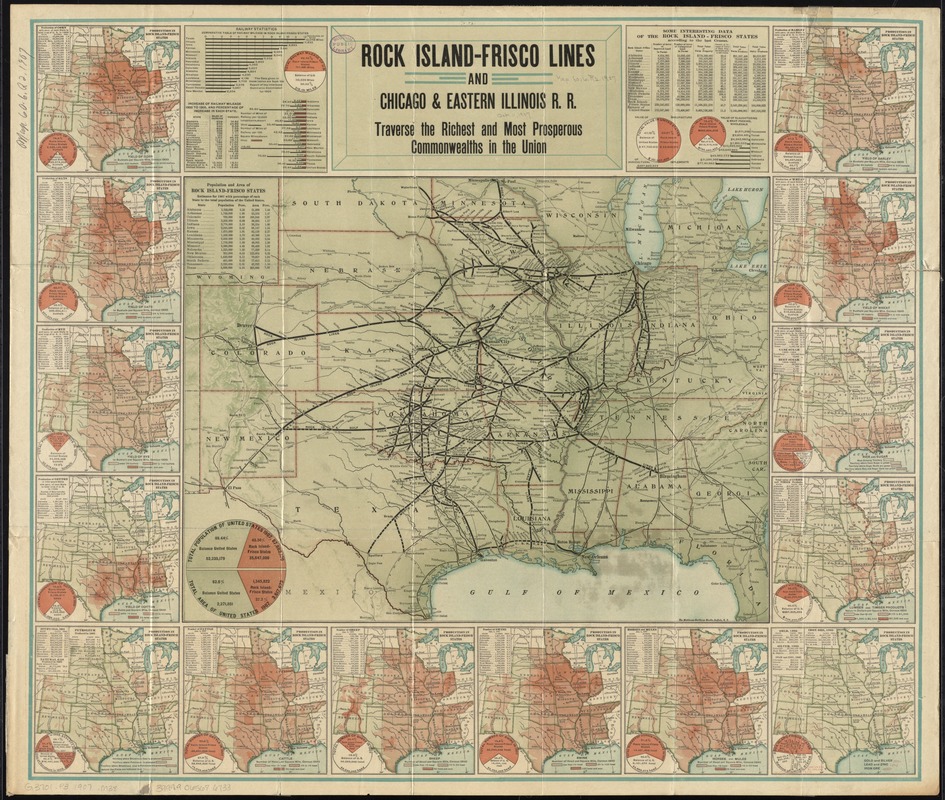

Matthews-Northrup Works

Rock Island-Frisco Lines and Chicago & Eastern Illinois R.R. ...

Buffalo, 1907. Printed map, 13.5 x 18 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center.

This map, promoting the Rock Island, Frisco, and associated rail lines, illustrates the variety and quantity of agricultural commodities produced in the central third of the country at the beginning of the 20th century. This region, which included much of America’s richest agricultural lands, encompassed 37 percent of the country’s total land area and 41 percent of its population. It produced over half of the crops of corn, oats, wheat, cotton, rice, and sugar, and livestock of cattle, swine, horses, and mules. Marginal inset maps and pie diagrams demonstrate the geographic extent and percentages of each agricultural product.

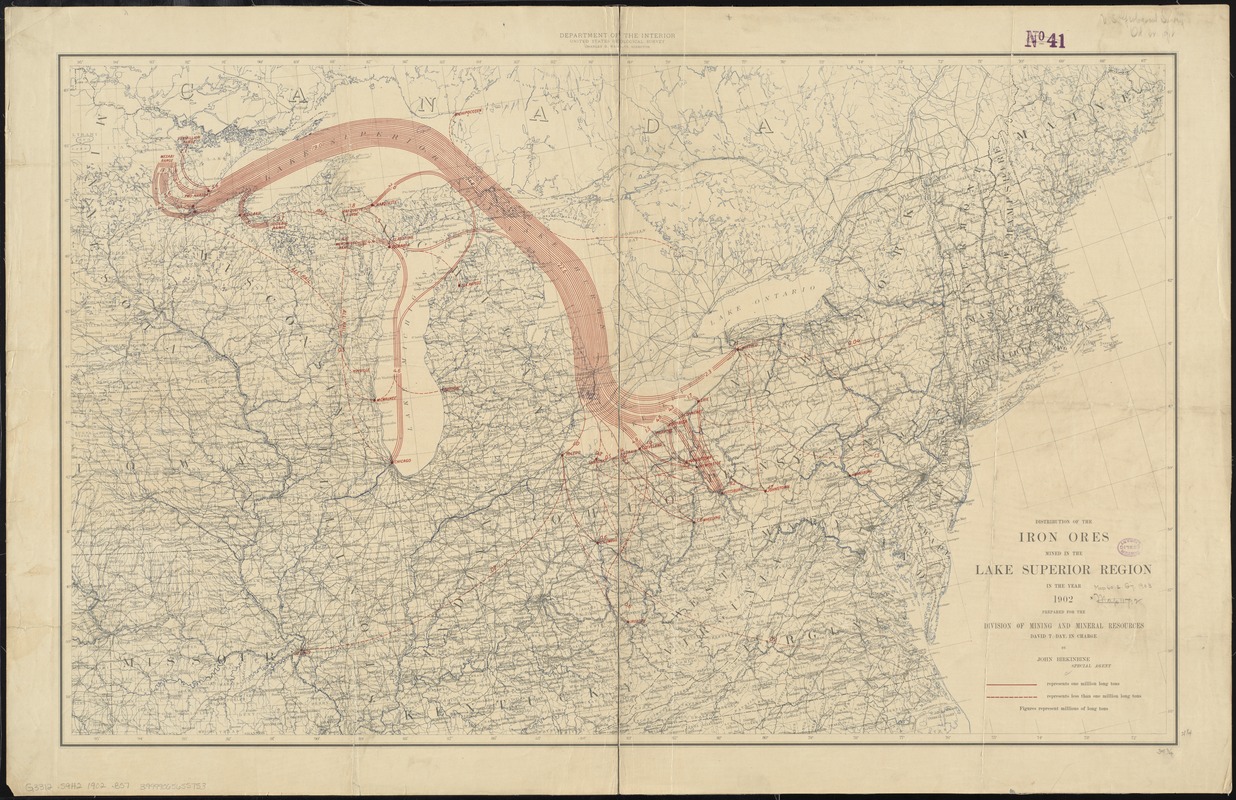

John Birkinbine (1844-1915)

Distribution of the Iron Ores Mined in the Lake Superior Region in the Year 1902

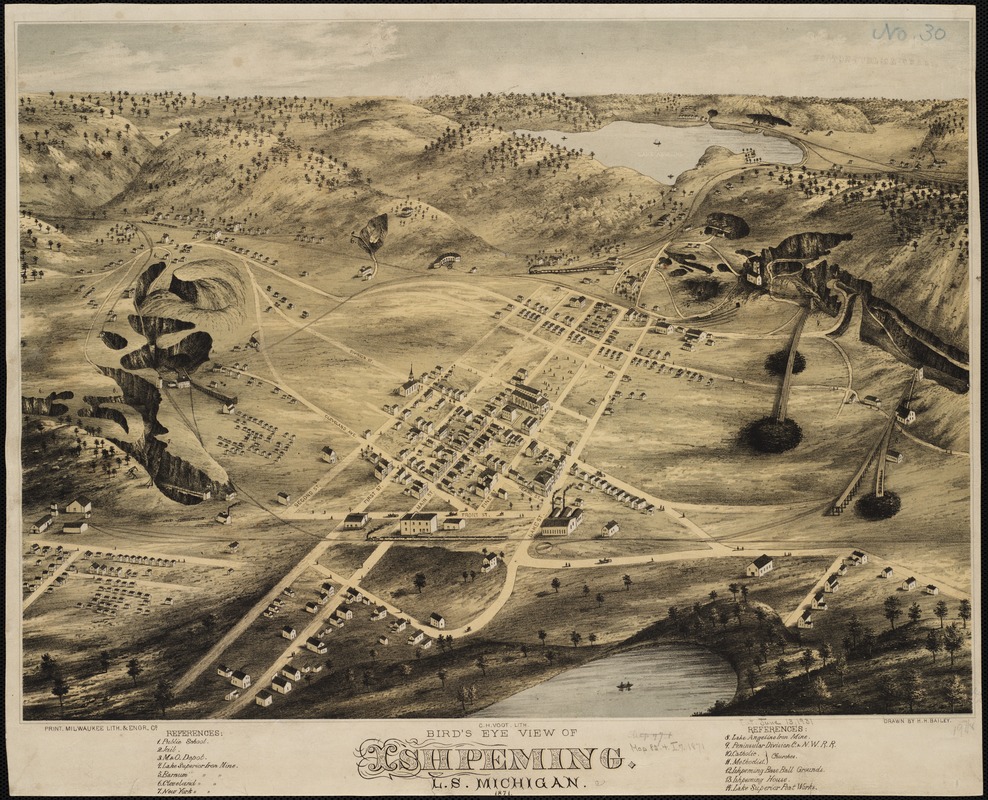

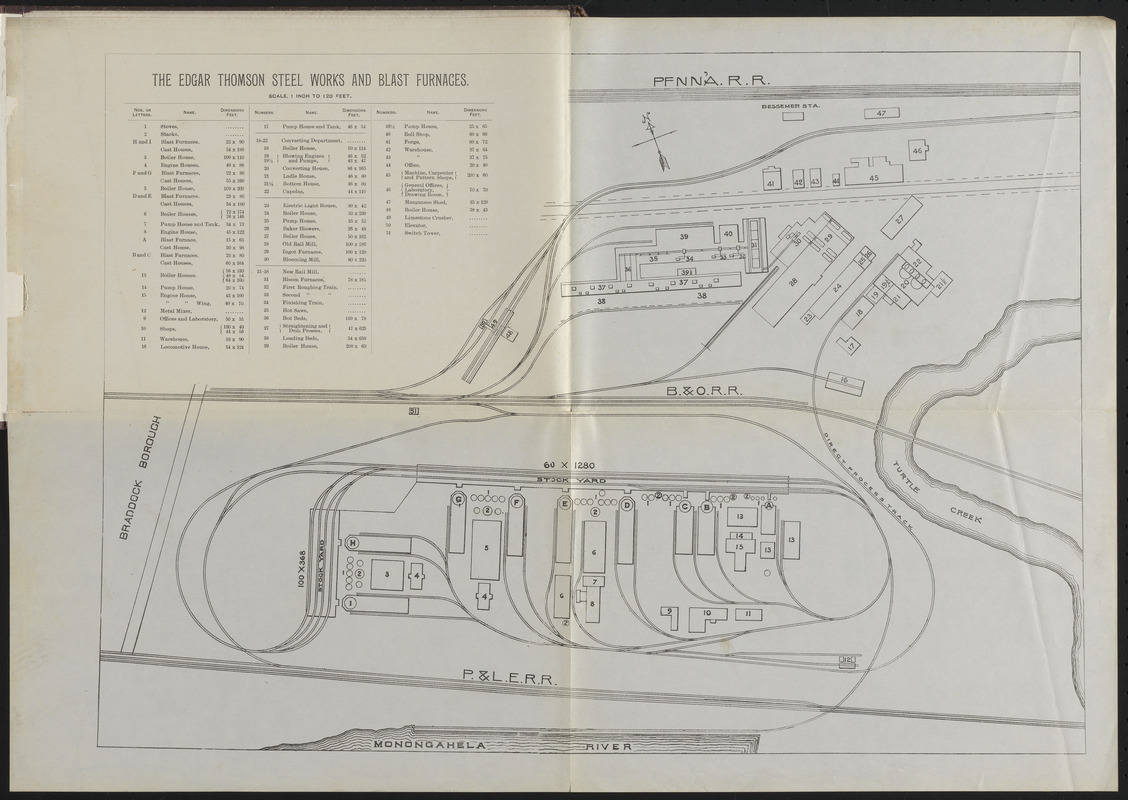

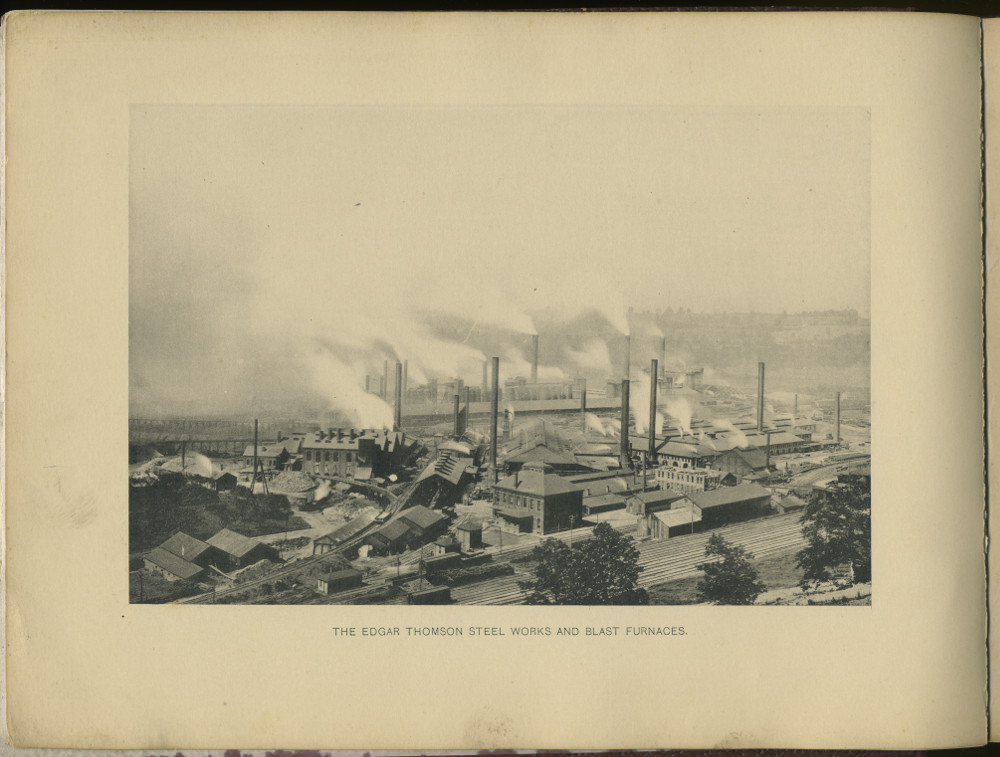

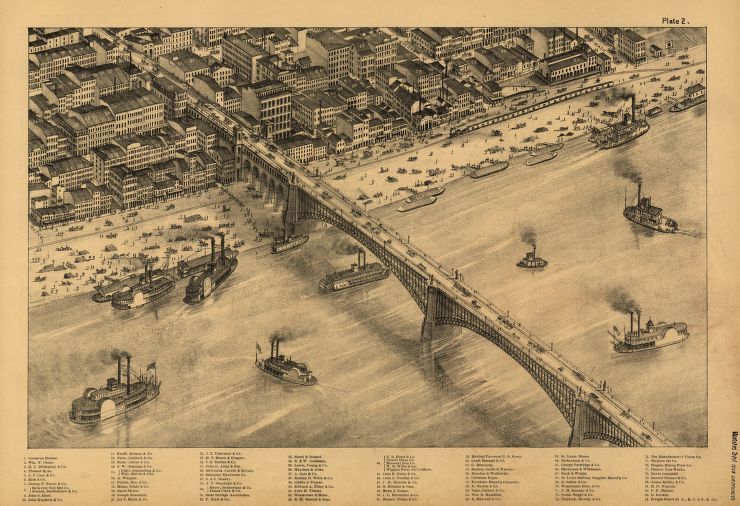

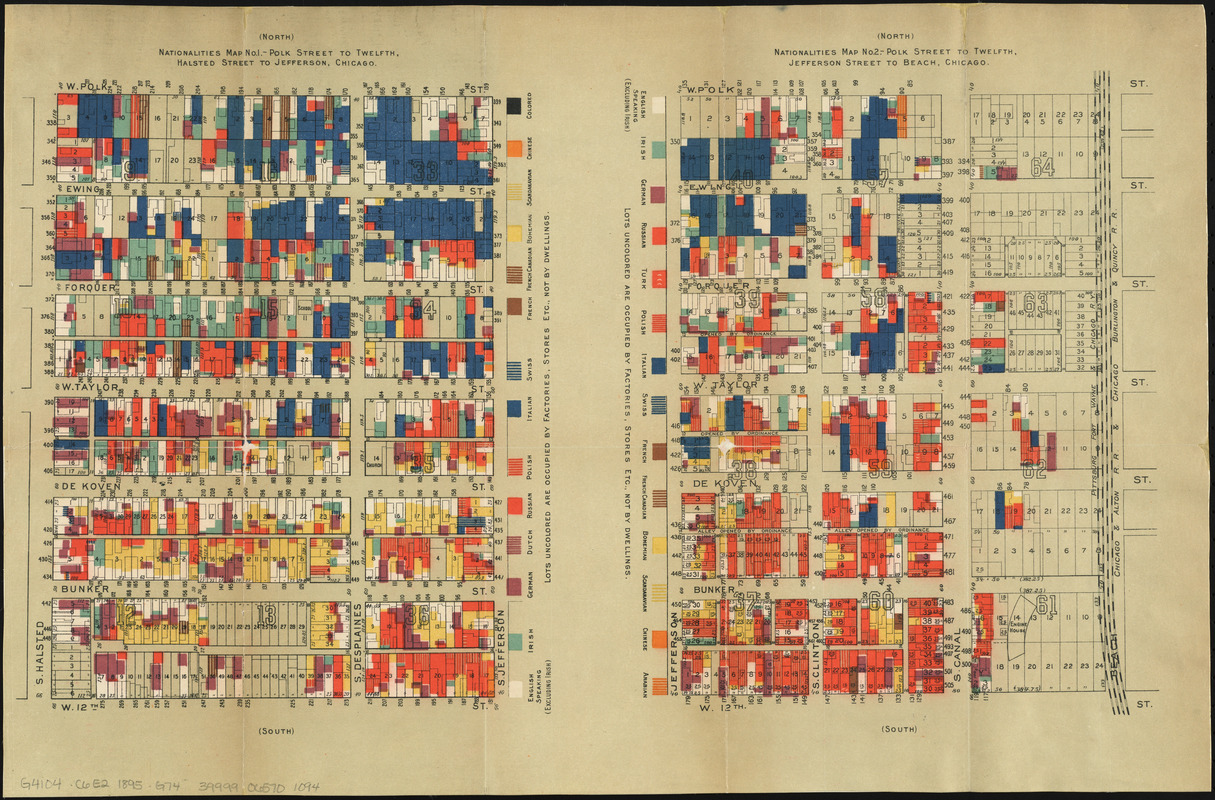

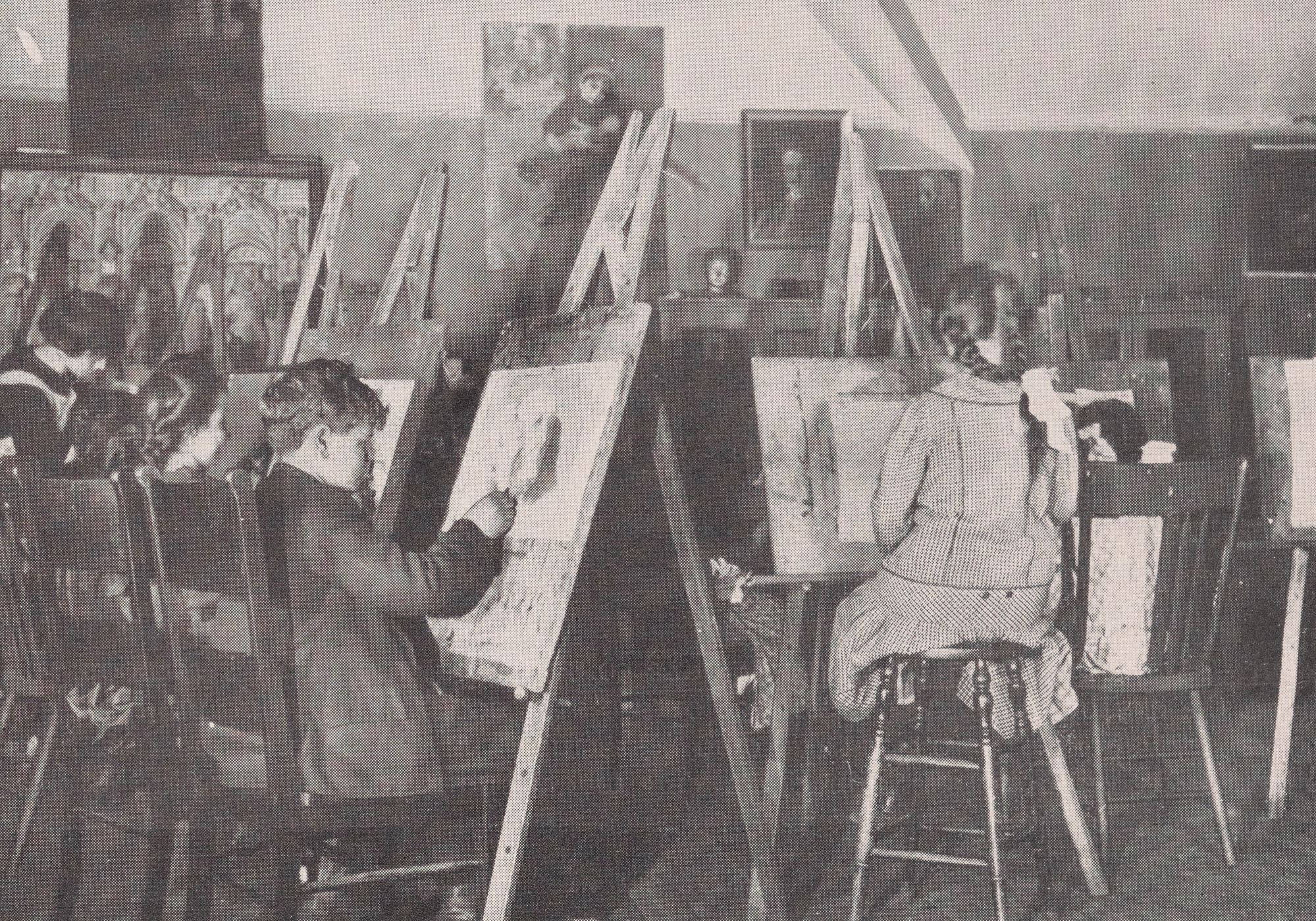

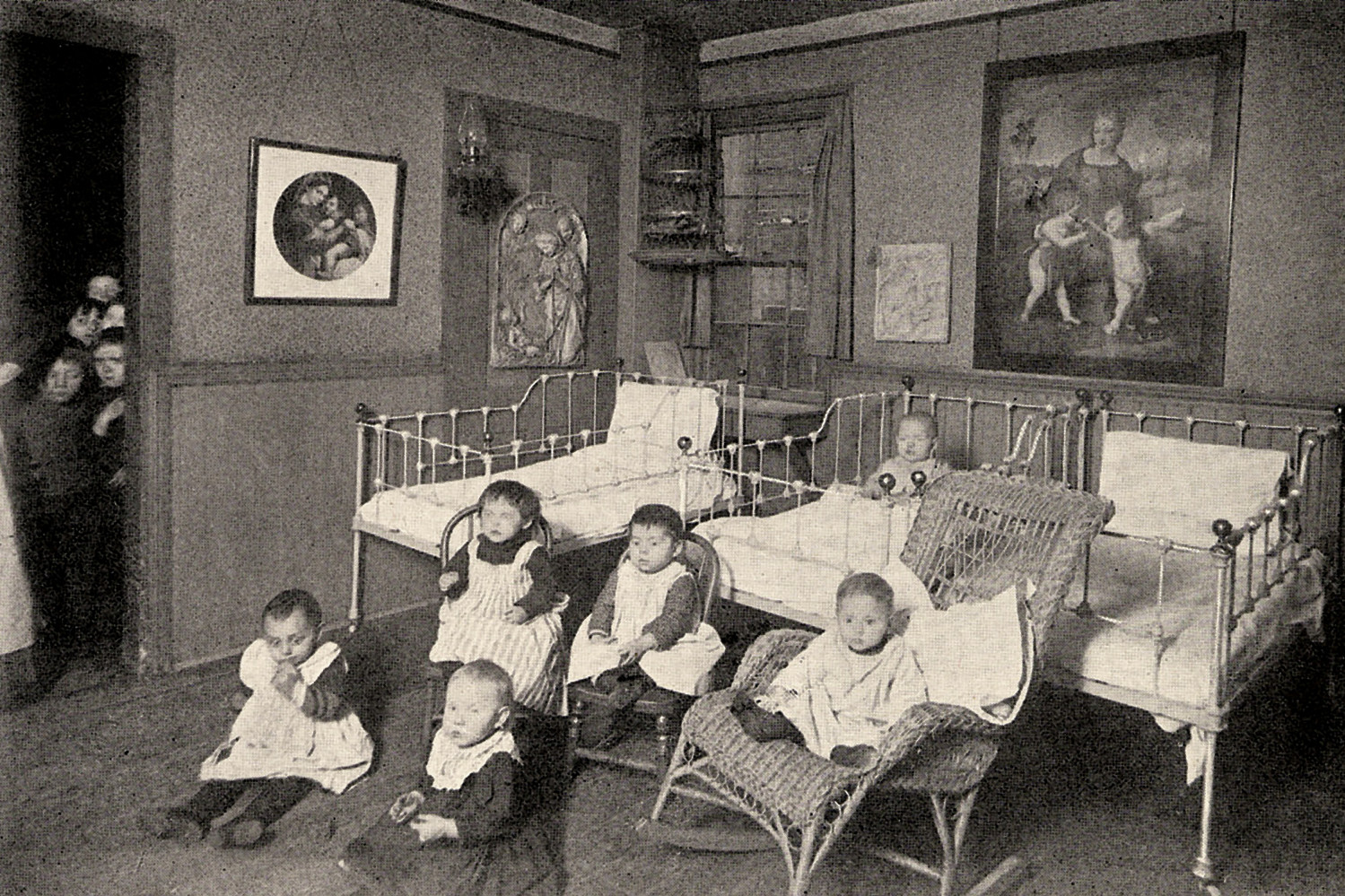

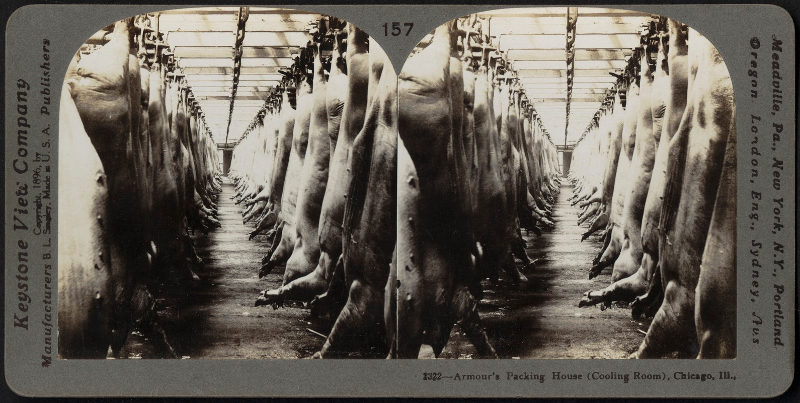

Washington, D.C., 1902. Printed map, 21.5 x 35 inches. Leventhal Map and Education Center. Reproduction 2019.