Introduction

One of the goals of Faces & Places is to create an environment that will inspire dialogue, encouraging us to understand each other's cultural heritage, learn how we are different, but still realize how much we have in common. In creating this exhibition, we selected a number of historical maps that portray the countries from which the greatest number of Bostonians originate. These maps depict the countries at various stages in their historical, geographical, political, and economic development.

According to the 2000 census, the eight countries whose immigrant population informs the cultural diversity of the city of Boston are Cape Verde, China, Dominican Republic, England, Haiti, Ireland, Italy, and Jamaica. Immigrants from each of the countries represented in this exhibition celebrate the culture that is their heritage in different ways in their new home.

Themes: Understanding the Exhibition

- Navigation and Exploration: As people began to travel beyond their borders, maps were used to provide increasingly accurate means to help plan and guarantee that the financial and physical risks they were taking would be as successful as possible.

- Remembering Home: Central to the immigrant experience is maintaining strong ties to one’s homeland and culture. Maps are often used to remind us that a powerful sense of place is a foundation for adjustment to one’s new land.

- Tourism: Travel for recreational purposes has increased and is no longer the purview of the very wealthy. Tourist maps are an integral part of this new demand for information about foreign places.

- Transportation: As the means of travel expanded on land and sea, so too did the ways in which these routes were portrayed on maps. Travelers were provided information that anticipated their needs as they went to unfamiliar places.

- Urban Culture: Cities play an important role in the journeys of all immigrants. Urban maps provide a detailed visual representation of changing landscapes informed by these multi-dimensional cultures.

- Global Interaction: Globalization during the last two centuries has increased interaction between nations with different cultures, often resulting in contentious encounters. Maps are an integral part of nations dealing with these challenges.

Boston, Massachusetts

Founded in 1630, Boston is one of America's oldest cities. Laid out on a narrow, hilly peninsula jutting into Boston Bay, the "Town of Boston" grew into a bustling seaport by the mid-18th century based on its commerce with many ports in the British colonial empire. Not only was Boston the main administrative center of British government in the Massachusetts colony, it was colonial AmericaԳ largest city until 1760, when it was surpassed by Philadelphia. Nevertheless, it continued to maintain its position as the primary port of entry for the New England region.

Without a rich agricultural hinterland like other colonial American port cities (i.e. Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Charleston), Boston in its early years turned to maritime interests including fishing, whaling, ship building, and shipping. Following the American Revolution, Boston was transformed from a colonial seaport confined by the physical limits of the Shawmut peninsula, to a large regional city. This feat was accomplished by creating new land adjacent to the peninsula and integrating the neighboring villages to the southwest, as well as the towns on the north side of the Charles River. Except for Hong Kong, Boston has the largest amount of man-made land in any city.

As Boston grew and prospered during the 19th century, it also became the hub of the regionԳ transportation network, with roads and railroads radiating out from the city to most parts of New England. In addition, extensive industrialization aided by an immigrant labor force supplemented BostonԳ commercial and financial success.

Throughout its history, immigrants from many countries have played a critical role in the development and economic vitality of Boston. While immigrants from England were responsible for establishing the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies in the 17th century, the English continued to be a major immigrant population in Boston throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Beginning in the early 19th century, Irish immigrants dominated the city. By the end of that century and throughout much of the first half of the 20th century, Italians provided the largest number of newcomers to Boston. As the 20th century came to a close, although England, Ireland, and Italy still accounted for much of the immigrant population of the city, new arrivals from China, the Cape Verde Islands, and the Caribbean island nations of Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Jamaica enhanced the colorful tapestry of culture and tradition in the city of Boston.

Justin Winsor (1831-1897)

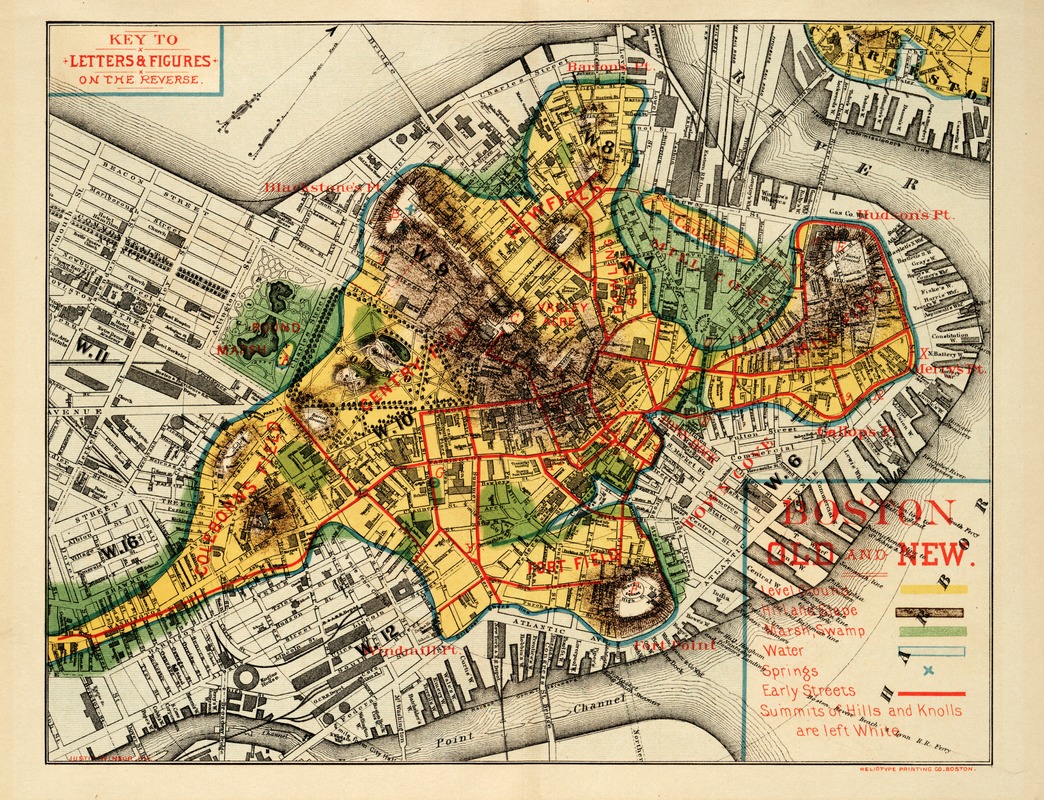

Boston, Old, and New

Boston, 1880

Noted historian and librarian, Justin Winsor created this unique map by superimposing the outline of the original Shawmut Peninsula onto an 1880 map of Boston. It was used as the frontispiece for the first volume of his Memorial History of Boston, Including Suffolk County, Massachusetts, published in 1882.

Though drawn without the assistance of computers or aerial photographs, it remains one of the most vivid diagrams of the radical transformation and enlargement of the Shawmut Peninsula during the 19th century.

Henry Pelham (1749-1806)

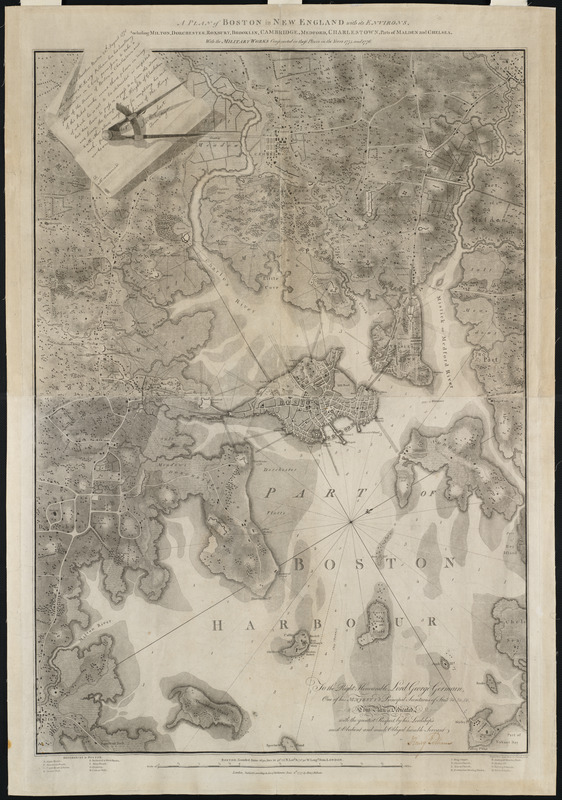

A Plan of Boston in New England

London, 1777

This most important battle plan of the New England theater of war shows, in detail, the American fortifications on Dorchester Heights forcing the British to leave Boston in 1776. This was the best printed plan of the city of Boston and its environs, to date. Finely engraved in aquatint and beautifully printed on heavy paper, this copy is one of perhaps six known examples signed in manuscript by the author.

Pelham, a Loyalist, was born in Boston in 1748/9. The note that was engraved in the upper left of this map is a copy of the passport issued to Pelham two months after the Battle of Bunkers-Hill, giving him permission to examine the enemy lines.

The aquatint is of interest, because of its high quality. It is known that Pelham consulted John Singleton Copley (Pelham's half brother) regarding the production of this map. Pelham was eleven years Copley's junior, and there is little question that Pelham learned to draw from his accomplished elder. The outstanding result is without question the finest cartographical print relating to the Revolutionary War.

Anonymous

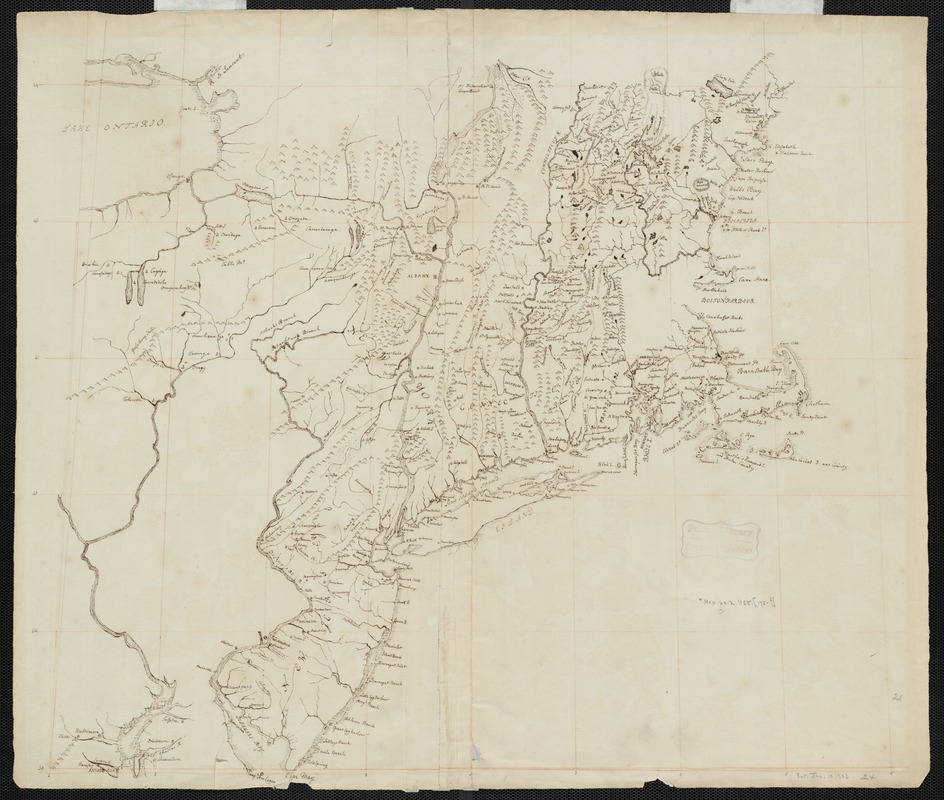

[Map of Coast from Maine to Delaware]

Manuscript, c.1750

This map is an unrecorded manuscript of the northeast part of the British colonies in America, showing in some detail the topography of the region and including names of towns, rivers, and harbors. Possibly produced for military purposes during the rise of hostilities between the French and English in America, the cartography appears to be based on both original French and English sources.

The geographic coverage of this map shows the North American coast from Casco Bay to Cape May, extending inland as far as Lake Ontario. It encompasses the British colonies in New England, as well as New York, New Jersey, and part of Pennsylvania.

Phillip Wells

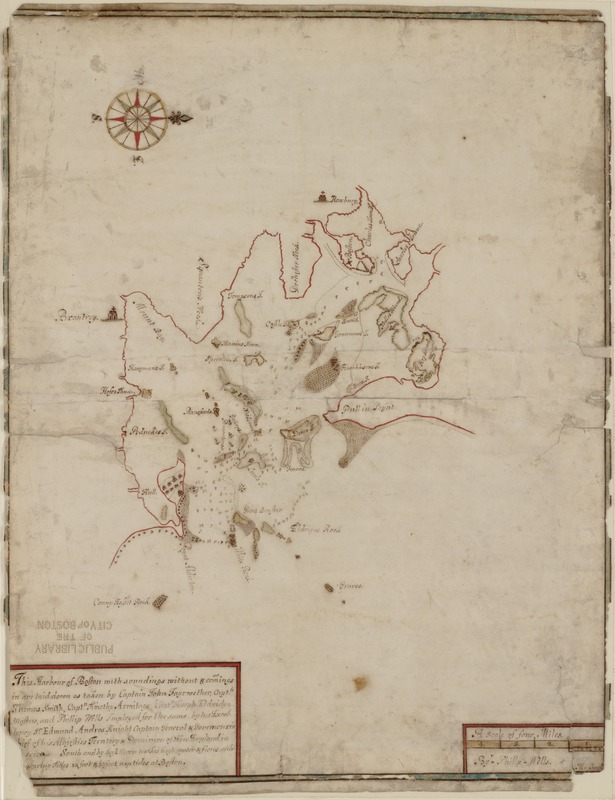

This Harbour of Boston with Soundings ... as Taken by Captain John Fayrwether, Capt. Thomas Smith ... and Phillip Wells...

Boston, c.1688

Although undated, this earliest surviving plan of Boston Harbor dates from the period of Sir Edmund Andros' term as governor of New England from 1685-1689. It is most likely one of several manuscript maps of New England sent by Andros back to the Board of Trade in London. Andros was known to have received orders to secure a map of Boston Harbor as early as April 1688.

The chart was prepared by Phillip Wells, one of the most highly skilled of early American cartographers, based on information provided by several ship captains. Few other important 17th-century manuscript maps of the New England colonies have survived.

It is also of interest that the earliest printed chart of Boston Harbor, which was published as part of The English Pilot: The Fourth Book (1689), shows many similarities to this map.

Cape Verde

This small group of islands off the coast of Africa was originally a Portuguese colony. It was one of the stops for Christopher Columbus on his voyages discovering the "New World". Used mostly as a gateway for the slave trade, the islands remained part of Portugal until achieving political stability. Many people emigrated from Cape Verde during the 1980s because devastating droughts caused economic activity on the islands to stagnate.

Jason C.

My name is Jason. I am an 8th grader from the Neighborhood House Charter School in Dorchester. I am 13 years old, and the middle child in my family. I have two brothers. My older brother is seven years older, and my younger brother is seven years younger. I am Cape Verdean. Cape Verde is an island off the West coast of Africa. The atmosphere is warm and the beaches are beautiful. In Cape Verde, we speak Portuguese and Cape Verdean Creole. I speak Cape Verdean Creole fluently with my family at home. My parents speak Portuguese, but I don't. My mother speaks five languages, and they are as follows: English, Spanish, Cape Verdean Creole, French, and Portuguese. My mom makes great use of her languages, because she works as an interpreter at Boston Medical Center. My parents came to this country about 20 years ago. I still have family in Cape Verde, who I last visited when I was seven. I look forward to visiting them again.

I visited Cape Verde in 1997. I loved it. I was visiting my aunts and uncle and my grandma. I was at the beach all day, every day. I was extremely warm, and the waves were awesome. There are ten islands in Cape Verde. The sandy beaches are beautiful. Some islands were volcanic, so the sand is black. The other islands have white sand that feels like silk under your feet. The water has a sapphire blue, crystal clear color to it. It is also warm and refreshing. There is a dance we call "pasada," which means passing. The dance symbolizes all negative things passing you by. And when you dance, you forget all bad things.

I am proud to be Cape Verdean, because that is what God decided to make me and that is what I will represent forever.

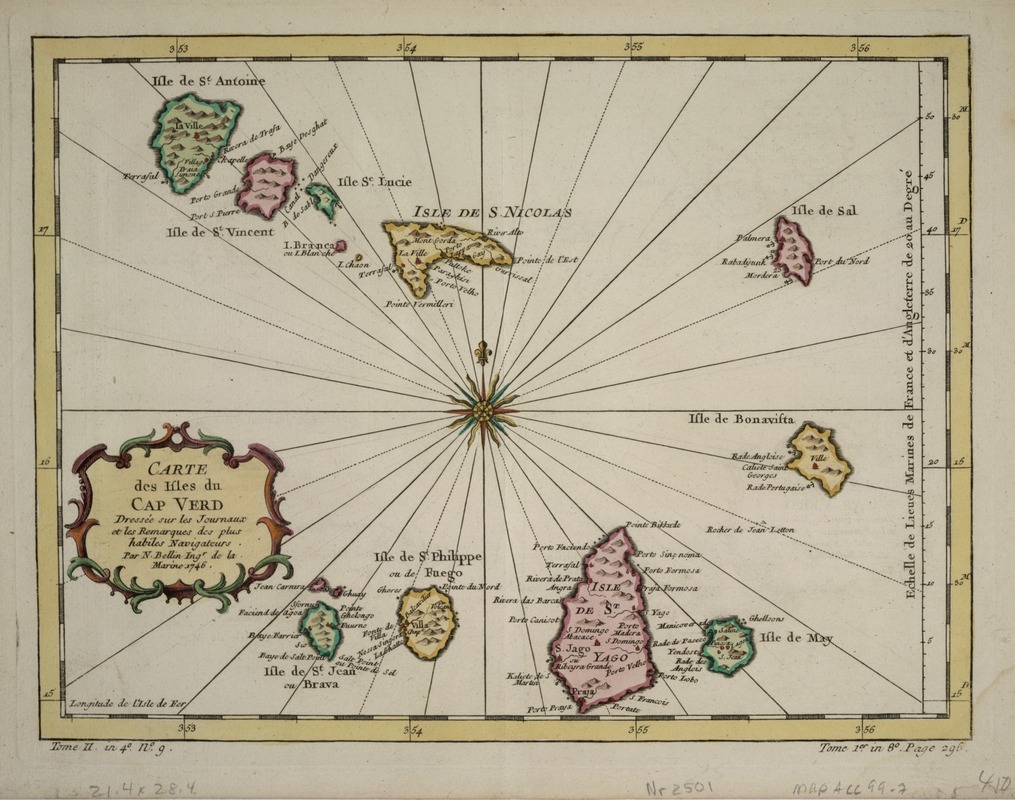

Jacques Nicolas Bellin (1703-1772)

Carte des Isles du Cap Verd dressee sur les journaux et les remarques des plus habiles navigateurs ...

Paris, 1746 (1780)

Although drawn and engraved in 1746 by Bellin, one of the most prolific mid-18th-century French cartographers, this map of the Cape Verde islands was published in the 1780 edition of Jean-Francois de la Harpe's Abrege de l 'histoire generale des voyages. The map depicts the Cape Verde Islands, a small group of volcanic islands located in the tropical waters of the Atlantic, about 15º north of the Equator and 385 miles west of the African country of Senegal.

These islands were discovered and settled by the Portuguese in the 1450s and 1460s. During the subsequent centuries, the French and British tried to gain control, but the islands remained under Portuguese domination until 1975 when they gained independence.

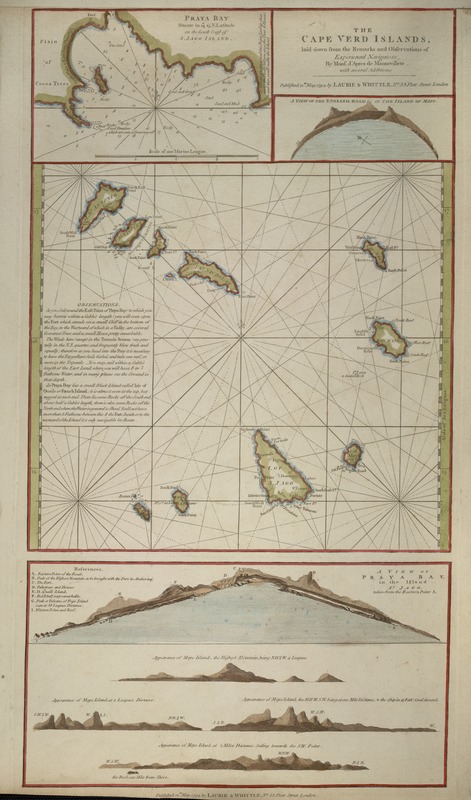

Jean Baptiste d'Apres de Mannvillette (1707-1780)

The Cape Verd Islands, laid down from the Remarks & Observations of Experienced Navigators…

London, 1794

Published by Robert Laurie and James Whittle, London mapmakers and engravers who were active in the early 1800s, this navigational chart used rhumb or directional lines to assist navigators in plotting their course to and from the Cape Verde Islands. The chart is based on observations recorded by the prolific French mapmaker Jean Baptiste d'Apres de Mannevillette.

The headland views or coastal silhouettes in the upper right and the lower insets of the map assisted sailors in identifying the various islands as they approached from the sea. The sidebar on the left even included tips for sailors, for example, "as you head into the Bay it is necessary to have the top gallant sails furled..." Upon entering Praya Bay on the island of St. Iago, the navigator could refer to the depth chart in the upper left corner to make a safe passage.

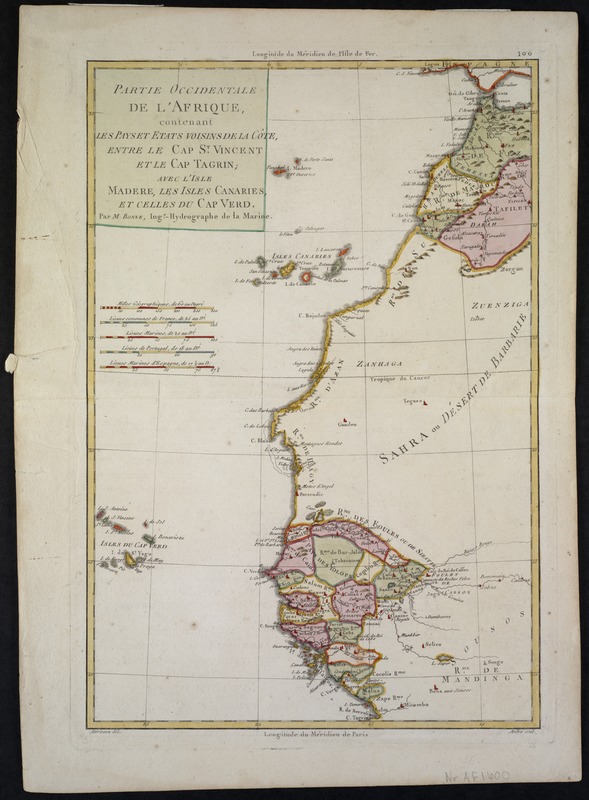

Rigobert Bonne (1727-1795)

Partie Occidentale de L’Afrique, contenant les pays et etats voisins de la côte, entre le Cap St. Vincent et le Cap Tagrin, avec L’Isle Madere, Les Isles Canaries, et celles du Cap Verd

Paris, c. 1770

Published by the French Depot de la Marine, this map of northwestern Africa depicts the settled tribal areas located north and south of the Sahara Desert. These brightly colored jurisdictions provide a stark contrast to the desolation of the desert itself, which dominates the center of the map. The coast line shown here runs from the Straits of Gibraltar in the north to Cape Tagrin and the Sierra Leone River in the south. The Cape Verde Islands appear at the lower left.

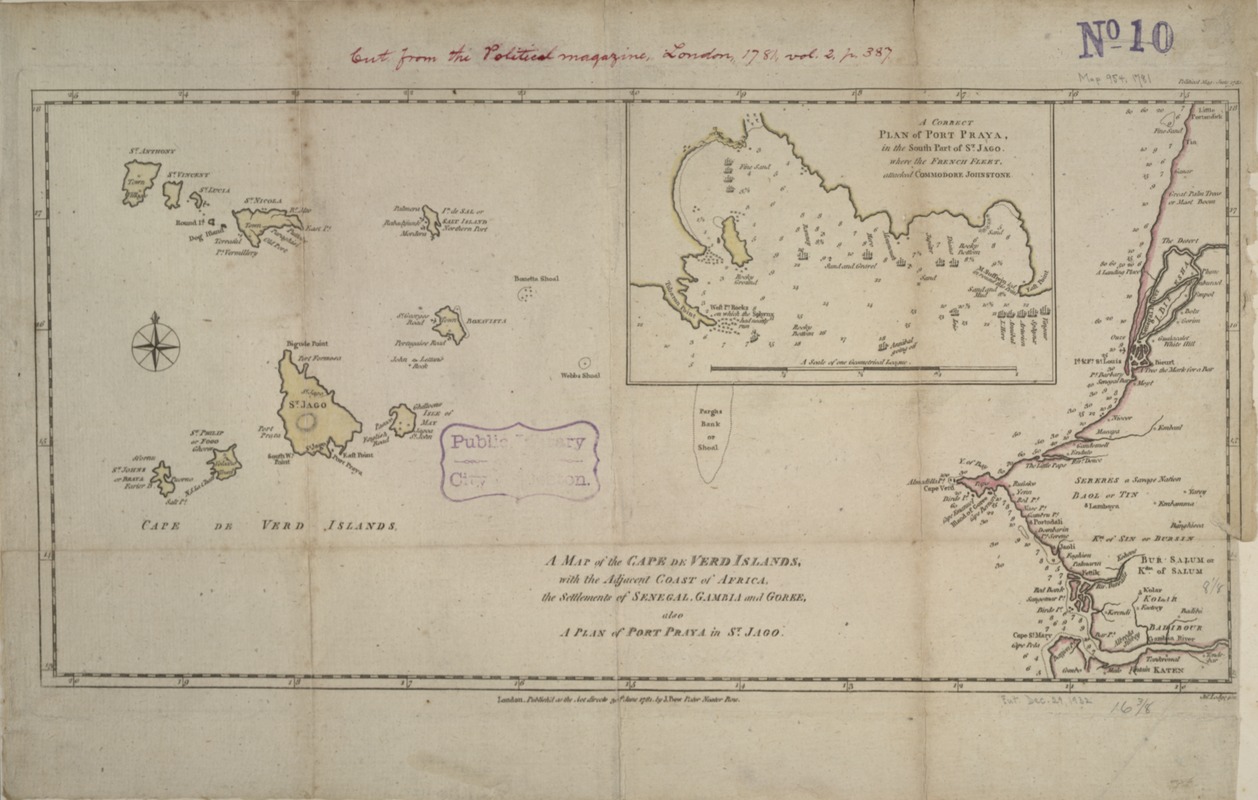

John Lodge (fl. 1755-1796)

A Map of the Cape de Verd Islands with the Adjacent Coast of Africa, the Settlements of Senegal, Gambia and Goree, also a plan of Port Praya in St. Jago

London, 1781

This map of the Cape Verde islands appeared in the second volume (1781) of The Political Magazine. Published by John Bew, a London bookseller, this journal was written for an audience of informed gentlemen and often included supplementary maps. The map provides detailed depth soundings along the African coastline and in the inset for Praya Bay. Currently, the town of Praya (Praia), located on the island of St. Jago (Sao Tiago), the largest island in the Cape Verde grouping, serves at the capital of the country which gained its independence in 1975.

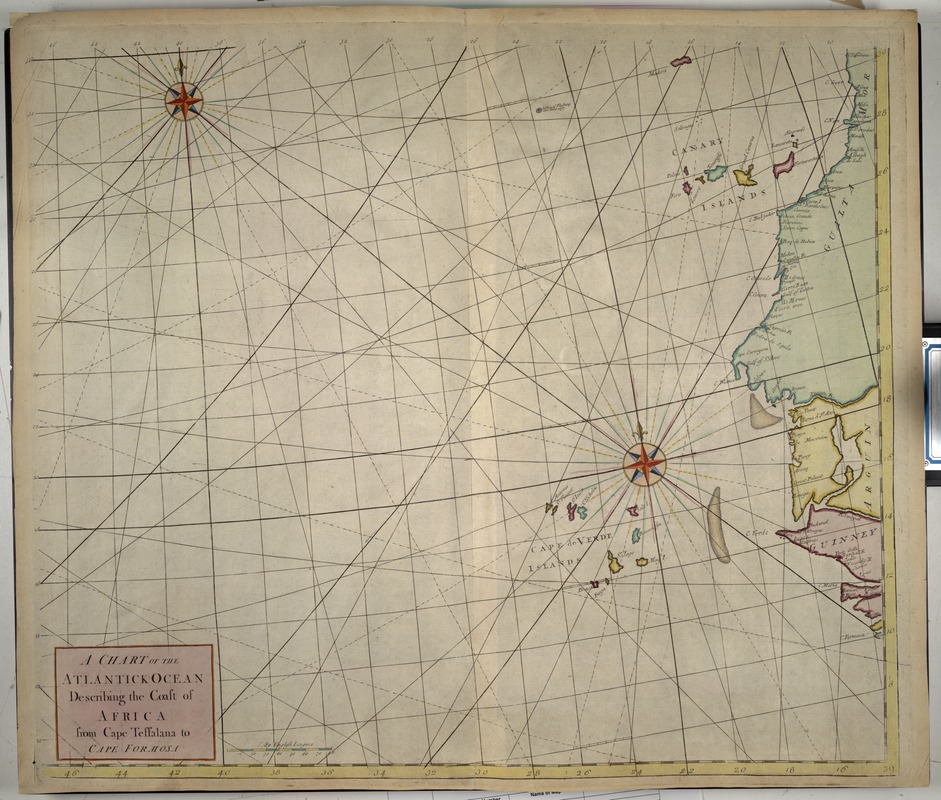

Anonymous

A Chart of the Atlantick Ocean Describing the Coast of' Africa from Cape Teffalana to Cape Formosa

London, c. 1725

This portolan-style chart, with two colorful compass roses and radiating rhumb lines, undoubtedly dates from the early 18th century. It was apparently part of a series of charts prepared to aid sailors in navigating the Atlantic trade routes along western Africa.

The geographic area depicted on this chart covers the North Atlantic from the Canary to the Cape Verde Islands and the west coast of Africa including portions of the present-day countries of Morocco, Western Sahara, Mauritania, Senegal, and Gambia.

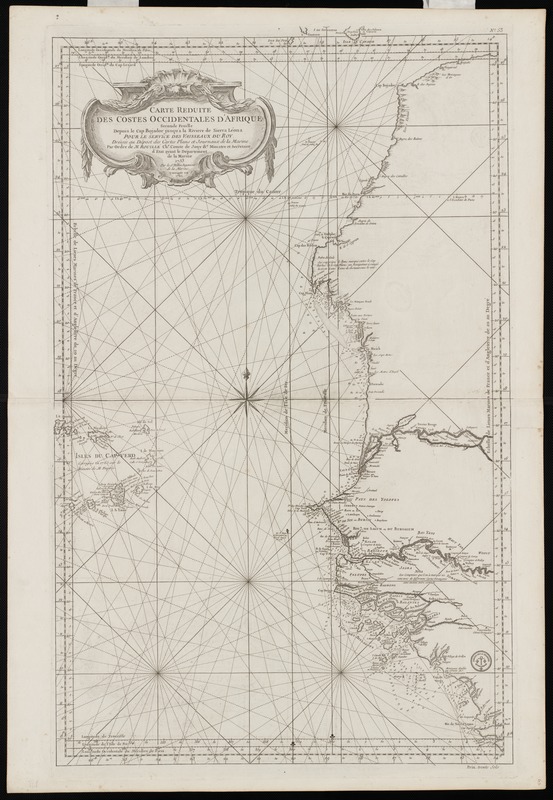

Jacques Nicolas Bellin (1703-1772)

Carte Reduite des Costes Occidentale d'Afrique

Paris, 1753 (1765)

This chart predates the standardization of the measurement of longitude from the Greenwich Meridian, located near London. During the 18th century, map makers could choose one of several points from which to measure longitude. In fact, this chart provides references to five meridians – Paris, London (Greenwich), Ferro (western most of the Canary Islands), Tenerife (largest of The Canary Islands), and Cape Lizard (a southwestern peninsula of England).

Prepared in the portolan-style, this chart contrasts nicely with modern navigational charts of the same region. They both have the same function -- to safely guide sailors through complicated and sometimes treacherous coastal waters.

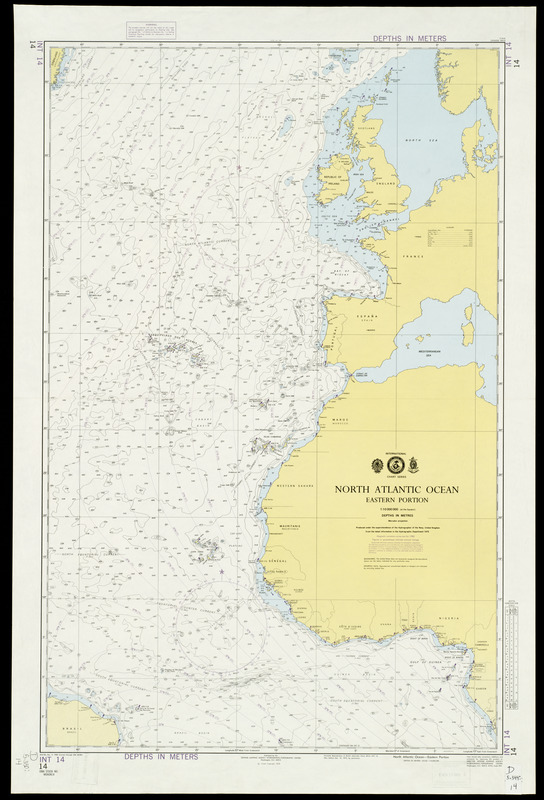

U. S. Defense Mapping Agency

International Chart Series, North Atlantic Ocean, Eastern Portion

Washington. D.C., 1983

This modern navigational chart provides depth soundings and navigational aids for the eastern portion of the North Atlantic Ocean. Using an extremely small scale (1:10,000, 000 at the Equator), it covers nearly the entire west coasts of Europe and Africa, north of the Equator. This chart demonstrates the relationship of the Atlantic island groups – the Cape Verdes, Canaries, and Azores – to Africa and Europe.

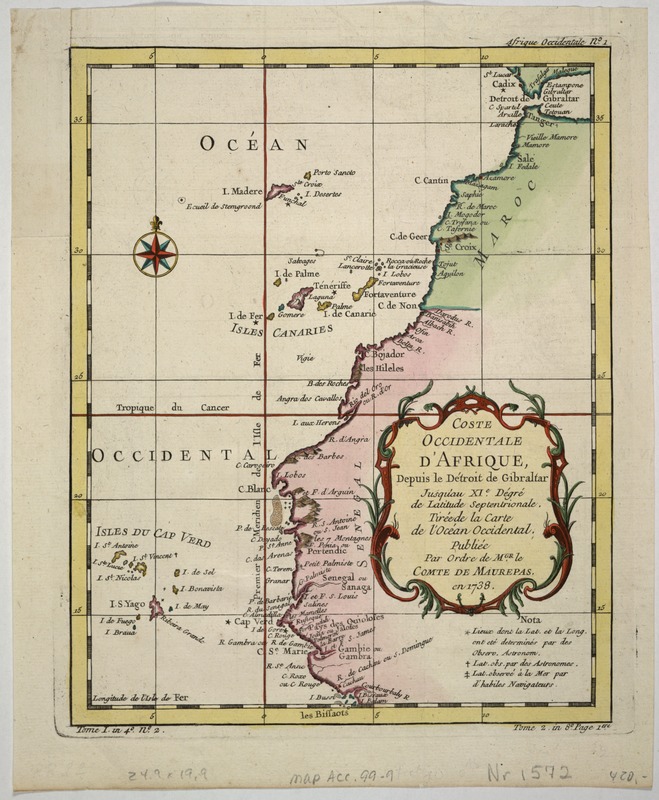

Jacques Nicolas Bellin (1703-1772)

Coste Occidentale d’Afrique depuis le Détroit de Gibraltar jusqu’au XIe dégré de latitude septentrionale

Paris, 1738

This map of the west coast of Africa was first engraved in 1738 by order of Jean-Frederic Phelypeaux, Count of Maurepas and Secretary of State under the French King Louis XVI. The map is a microcosm of African colonialism during this period; the Cape Verde islands were in the hands of the Portuguese, the Canaries were occupied by the Spanish, the French controlled Senegal on the mainland, while Morocco, incredibly, remained independent.

With much at stake for the occupying power, accurate maps were of critical importance for navigators and politicians alike. The accurate placement of islands was especially important for navigation -- hundreds of ships had been lost on the rocks or islands that appeared where the ship's navigator did not expect them to be. Hence, the emphasis in this map on accurate longitude of capes and islands, and the legend in the lower right corner explaining the method used for determining latitude and longitude for particularly dangerous locations.

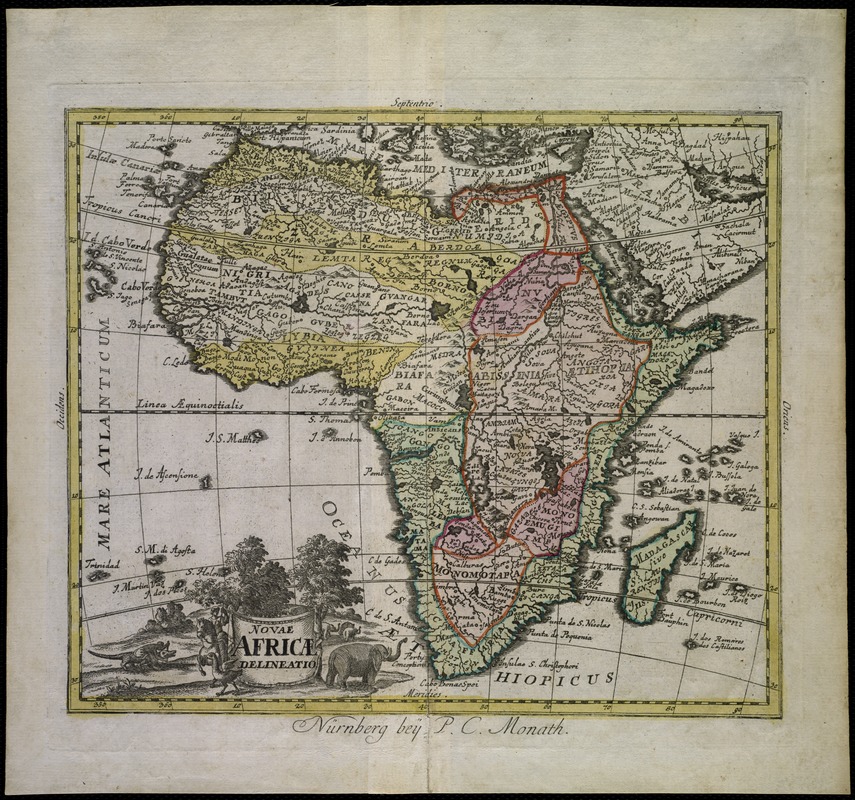

Peter Conrad Monath (1683-1747)

Novae Africae Delineatio

Nuremburg, c. 1769

This mid-18th-century map of Africa includes fictitious place names that are often found in African maps of this era, such as the mysterious and mostly unexplored interior regions here called Monomotapa and Monoemugi, located in southern Africa. Monomotapa, far from being the name of a nation, was in fact the name used for the leader of the Makaranga tribe that lived in south central Africa. For reasons unknown, it became a standard geographical designation during this period and is found on numerous maps of southern Africa as the name of a nation, not of a person.

While the interior parts of Africa were still relatively unknown to Europeans during the mid-18th century, maps from this time period show relatively accurate information for the coastal areas. In addition, the Cape Verde and Canary Islands, which were well known to the Europeans, are fairly accurately depicted in the northwest corner of this map.

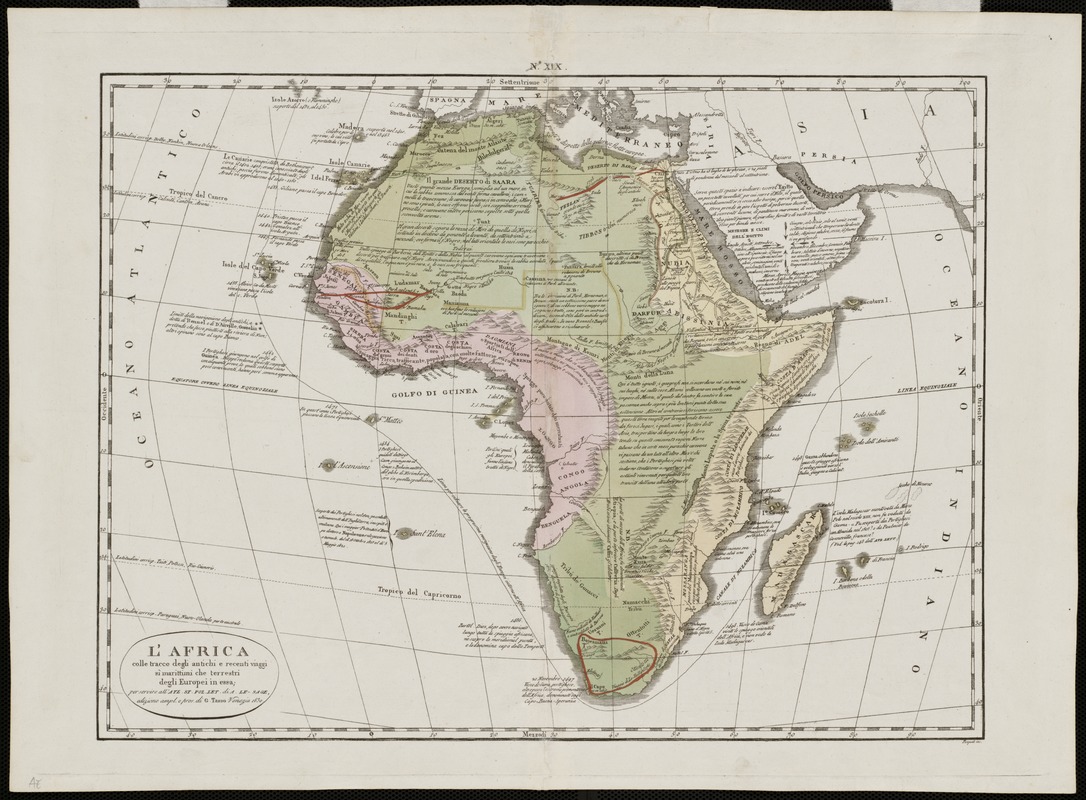

Emanuel Auguste Dieudonné Le Sage (1766-1842)

L’Africa, colle tracce degli antichi e recenti viaggi si marittimi che terrestri degli Europei in essa

Venice, 1830

This fascinating map of Africa comes from a revised Italian edition of Le Sage's Atlas Historique, first published in London in 1802. This atlas was also published for several decades in foreign editions, one of which was Italian, by Girolamo Tasso in 1830.

The map includes historical comments about early European exploration of Africa, with mention of the 15th-century Portuguese voyages to the Canary and Cape Verde Islands and along the west coast of the continent. There are also comments about the voyages of Vasco de Gama in 1497 and 1498 around the Cape of Good Hope and Marco Polo's voyage to Madagascar. Shown in red are the inland routes taken by 18th century explorers such as Frederick Horneman (from Cairo in 1798), Mungo Park (Gambia in 1795), and Francois le Vaillant (South Africa in 1781).

Le Sage, whose real name was Emmanuel Marie Joseph Auguste Dieudonné, Comte de Las Cases, took on the pseudonym Le Sage, because, in his words, he wanted to preserve his family's name and honor from desecration by would-be critics of the Atlas. He accompanied Napoleon during his imprisonment on the island of St. Helena from 1815 to 1821, and later published the former Emperor's memoirs under his given name. It is not a coincidence that this map points out and describes the island of St. Helena in the southern part of the Gulf of Guinea, and describes Napoleon's imprisonment there.

China

Boston established trade with China as early as 1784. During the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century this trade connection brought many Chinese to Boston. by the late 1800s, economic and political troubles in China resulted in an increase in Chinese immigration to Boston. This Chinese population lived in a close-knit community that became known as "Chinatown".

Living in the Chinatown community helped these new immigrants maintain a connection to their culture as well as protection from discrimination. The largest influx of Chinese immigrants came as a result of the Chinese Civil War and the Communist victory in the 1940s. Because of its well-established Chinese community and the anti-Communist sentiments of the United States, many of the fleeing refugees came to settle in Boston.

Szu-Chieh Y.

I remember when my parents were talking about moving. At first I thought that we were just going to move to a new house or a new city, but never did I think we were going to move from Taiwan to America. I had just come home from a long hot day of school. For nine hours I was in a small classroom with forty-five other kids. The temperature that day was 90 degrees as usual. When I got home, I had tons of homework. Normally my homework took about three hours to do, but that day I had four hours of homework because kids in my second grade homeroom class were throwing paper balls. I got home at 3:00. I knew if I didn't start my homework soon it would take until ten o'clock to finish. So I got out a few pieces of lined paper, a sharpened pencil, and started working. I had to make sure that I finished all of my homework that night because if I went to school the next day with missing work my homeroom teacher would hit me with a long thin bamboo stick that hurts so much it makes you cry.

In school everyone was trying to get the perfect grade, and it was rare for someone to get a 70 on a test. All the parents pressured their kids to be the smartest. My parents didn't really care about pushing me to make the A. They wanted me to enjoy school instead of stressing me to be the best. I was half way done with my homework when my mom told my sister and me to come downstairs. "I have some good news," said my mom. "We are moving." I got so excited. "Where" I said, "Are we moving to a new town?" "No," said my mom. "A new city?" No. "A new state?" No. "Disneyland?" said my little sister. "No," my mom said for the last time. We are moving to America," my father finally said. My family looked glad like it was something good. I didn't know about them, but I wasn't ready to let go of all my family, all my friends, my house, and I wasn't ready to give up my life in Taiwan. "Why?" I asked my mom. "Because we think going to America will make things easier for us, you know better schools, and a cleaner place to live with no pollution," said my mom. That night I didn't even finish my homework. I couldn't concentrate because I had too much on my mind. I didn't even care if I got hit, I can take the pain.

Two weeks passed and everyday I could see people moving our stuff away. My house was now missing chairs, tables, and other furniture. It looked like an incomplete dollhouse when I walked in. I could only bring a few dolls and books. "Nothing heavy," my mom said. "We'll get more new toys when we are in America." But I didn't want more toys. I liked how things were.

Finally the day came, we were leaving that Monday afternoon and leaving everything behind. I took one last look at my house it was empty as a drum but I could still picture where all the furniture used to be. As I walked out of the house, so many memories just rushed through my mind like I was shot by a thousand bolts of memories.

When I got on the airplane, I thought to myself that in 23 hours I would be half way around the globe. When we landed in San Francisco a tall man with light blond hair came up and spoke to me in strange words I had never heard before. When I arrived in Boston I lived in my aunt's house. She was very rich and we came together with my other aunts and uncle. My wealthy aunt had nine rooms in her house. We lived on the third floor for nine months.

I remember my first day in an American school. I entered class with about 16 students it was less than half of the students in my old class. Everyone came from different countries, but they all knew how to speak English. Many kids came up to me and started talking and I had no idea what they were saying. So I would say to them, "Me no English go away!" I felt stupid for a while I had no clue what was going on in the class. The only thing that I understood was math. In Taiwan, we were way ahead with our mathematics. I had already memorized the multiplication table from 1-12 while they were still learning it. When my teacher gave me my first American homework I didn't know how to do it. So that night I just went to sleep. The next day I thought I was going to get hit, but all the teacher said was "that's okay, at least you tried." I was amazed no teacher in Taiwan was that nice to me before. Maybe it was a good thing that we moved and maybe it will all work out for the best.

James Wyld (1812-1887)

Map of China compiled from original surveys & sketches

London, 1842

In addition to the towns and topographical features of China, this detailed map includes notes identifying mines, forests, and mineral resources. For example, there is a reference to gold in the rivers of Szechuan Province. Other notes describe the culture and achievements of the Chinese and neighboring peoples. In Burma, for example, live the Paulaungs, who were, according to Wyld, "entirely employed in cultivating tea." The Great Wall is depicted in part and described as 1,500 miles long and varying in, height from 20 to 30 feet.

W.L. Maury and S. Bent

Chart of the Coast of China and of the Japan Islands including the Marianes and a part of the Philippines…

Washington, D.C, 1855

Published by the U.S. Navy, this map of the coast of China and Japan was the direct result of Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s ground-breaking diplomatic journey to Asia in 1853 -1854. Among the goals of the expedition was the completion of coastal surveys of China, Japan, and other nations in this region. The missing Korean coastline provides evidence that Perry did not travel as far north as Korea.

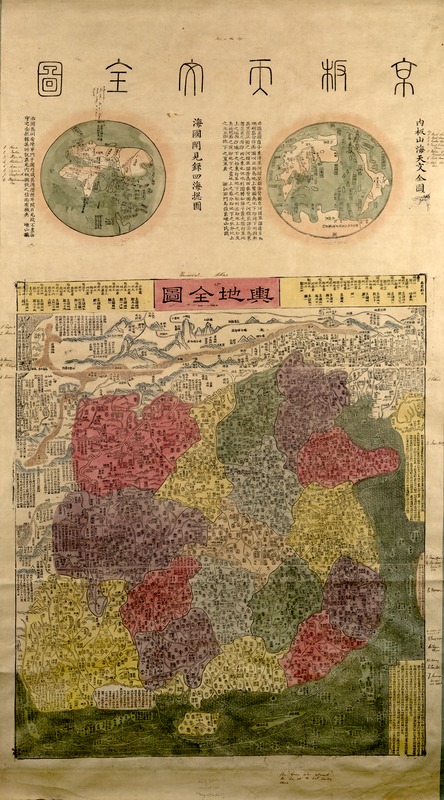

Jungmen Chen, for Jinliang Ma

[Universal Map of China]

Woodcut, mid-19th century (late Ching dynasty)

A Chinese view of the world is provided by this unusual woodcut and hand-colored map. The primary emphasis is China, but Europe and the British Isles are represented as a very thin sliver of uncolored land and islands in the upper left corner. The upper two vignettes, however, depict the world in the European context of two hemispheres – to the left are Eurasia and Africa, and to the right, Asia, Antarctica, and the Americas.

The seventeen provinces of China dominate the main section of the map. They are outlined and colored, with cities, towns, and villages indicated by woodcut stamps of their names. Rivers, mountains, the Great Wall of China and the Gobi Dessert are also depicted using simple pictorial symbols.

A late nineteenth-century commentator has translated into English several of the Chinese labels. As is typical for world maps from non-European cultures, distant lands are depicted as mysterious and exotic. For example, a note on Brazil identifies it as the "land of the cannibals."

The map includes several clues as to its origin. In the upper left vignette, China is identified as the "Qing Empire," implying that the map dates from before the fall of the Ching dynasty and the Chinese Empire in 1911. In addition, a late nineteenth-century handwritten note in the lower right margin refers to a rebellion in "Yung Ngan," almost certainly the Muslim Rebellion that took place in the province of Yunnan between 1855 and 1873. The text block at the upper left includes a reference to one "Jungmen Chen," the cartographer, while in the central upper text block, the patron who commissioned the map is identified as "Junliang Ma, from the Zhejiang province."

John G. Bartholomew and Gilbert N. Grosvenor

The National Geographic Magazine Map of China and its Territories

Washington, D.C., 1912

On February 4, 1912, P'u Yi, the last emperor of China, abdicated the throne with these words: "Today the people of the whole empire have their minds bent on a republic, the southern Provinces having begun the movement, and the northern generals having subsequently supported it. The will of providence is clear and the people's wishes are plain. How could I, for the glory and honor of one family, oppose the wishes of teeming millions? Wherefore I, the Emperor, decide that the form of government in China shall be a Constitutional Republic."

With the advent of a constitutional republic in China, Westerners for the first time had access (albeit limited) to China's extraordinary treasures. The National Geographic Magazine devoted its entire October 1912 issue to China -- its canal infrastructure, the Forbidden City, and its artistic, cultural, and architectural treasures. This map, which was included with that issue as a special supplement, was based on the cartography of the British firm, J.G. Bartholomew.

George Washington Bacon (1830-1922)

Map of China, Burma, Siam, Annam &c.

London, 1900

Much has changed in Southeast Asia, the part of the world depicted on this map, since it was printed in 1900. For example, the nations of Annam and Siam are now known as Laos, Cambodia, Viet Nam, and Thailand. There are several insets that both put the map in a larger context and provide closer detail. The lower right inset shows land and sea routes in and around China, while the surrounding insets focus on the cities of Peking, Shanghai, and Canton. One special symbol identifies certain cities along the coast or major waterways in China as so-called "treaty ports," special urban centers that had been granted foreign commerce rights by the Chinese government.

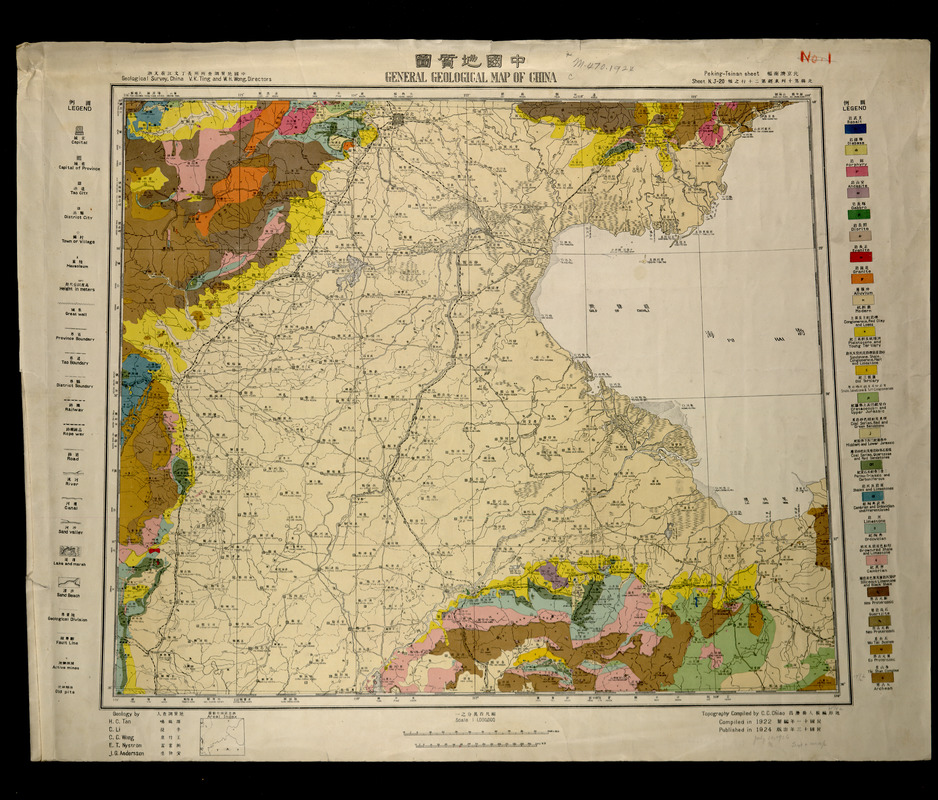

C.C.Ch'iao, H.C. Tan, and others

General Geological Map of China, Peking-Tsinan Sheet

[Peking], 1924

In this geological map of part of northeastern China, the result of a nationwide geological survey, the colors represent different mineral resources, such as basalt, clay, granite, or limestone. In addition, the location of railway lines, political boundaries, fault lines, active and retired quarries, and elevations suggest to the user of the map, where to find and extract natural resources and how and where to transport them. Interestingly, legends and text are provided in both Chinese and English, increasing the map’s usefulness to an international audience.

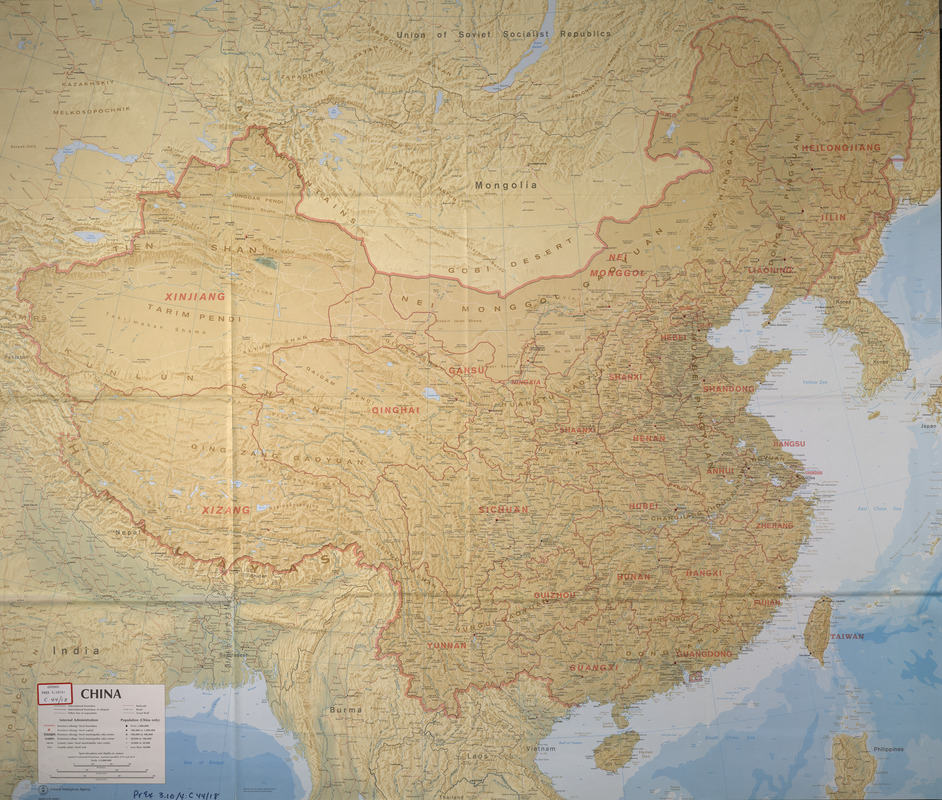

U.S. Central Intelligence Agency

China

Washington. D.C., 1979

The Central Intelligence Agency is known for publishing high quality and detailed general reference maps. This map of China, made during the height of the Cold War, is no exception. In addition to the detailed representation of settlements, topographical features, waterways, and provincial boundaries, the alphabetical gazetteer on the back locates, with precision, some 2,500 Chinese cities and towns.

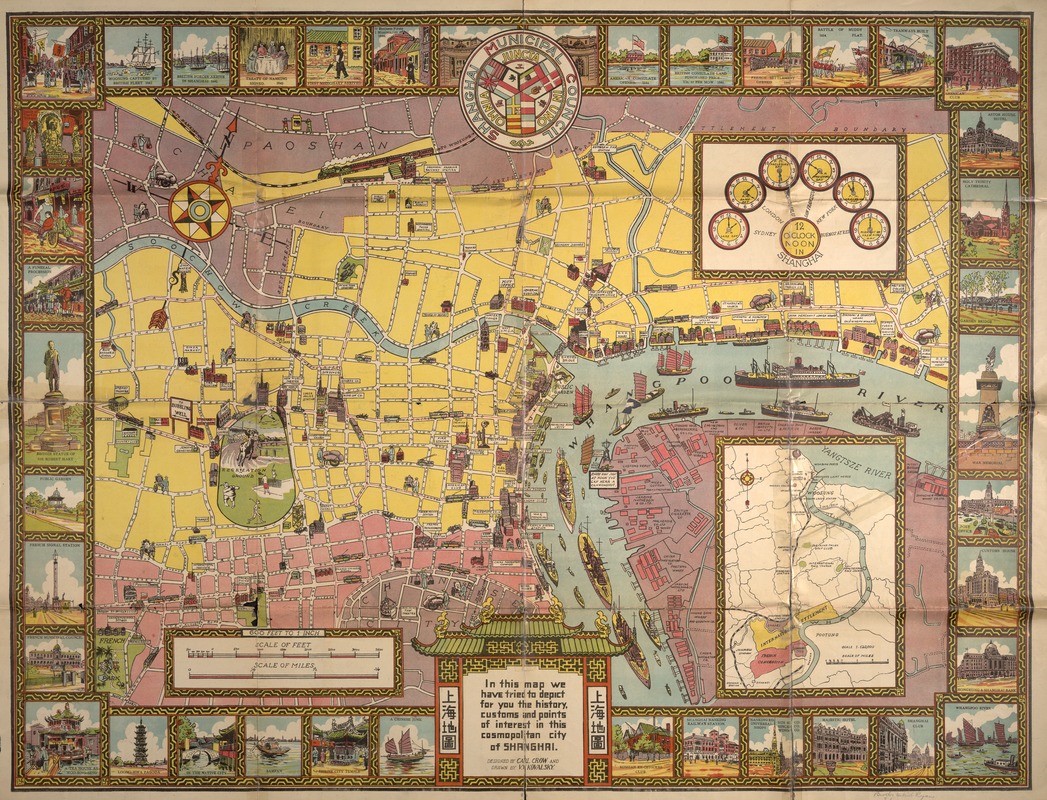

Carl Crow (1883-1945) and W. Kovalsky

[Illustrated Historical Map of Shanghai]

Shanghai, c. 1935

American journalist and advertising executive Carl Crow designed this colorful and user-friendly map of Shanghai. He was the founder of the Chun Mei News Agency, which was responsible for translating and disseminating English language news printed in Shanghai into Chinese. He also wrote over a dozen books about China including several travelers' guides. The vignettes around the map show important moments in Chinese history as well as facades of buildings and cultural monuments.

The Shanghai Municipal Council, who sponsored the preparation of this map, was an international governing body that was active in Shanghai from 1863 until the Japanese occupation in 1941. The seal of the Council demonstrates the international flavor of Shanghai in the early 20th century, with flags from twelve nations represented. Adding to the international flavor of the map is the diagram showing the time differences between Shanghai and cities around the world. The inset map at the lower right places Shanghai in geographical context, and also shows a basic outline of the different "settlements" of the city -- Chinese, French, and "International" (i.e., British and American). For some time, each of these settlements functioned as a miniature principality, administered and managed by its expatriate citizens. This assumption of Chinese authority angered many Chinese Shanghai residents and led to civil unrest. In retrospect, the motto of the Council, "Omnia juncta in uno" (All joined into one), seems rather optimistic in the face of Chinese disenfranchisement and discontent.

England

In 1620, a group of Pilgrims fled religious persecution in England and sailed on the Mayflower to America. The group landed in Plymouth and established a colony. In 1630, with Puritan settlements around the Massachusetts Bay area, a group of settlers established Boston, named for a town in Lincolnshire, England. Between the years of 1630-1643, 20,000 Puritan English men and women arrived in Boston and the Massachusetts Bay Colony. This massive migration was the result of tensions brewing in England between Protestants and Anglicans that would eventually lead to the English Civil War of 1643. Throughout the next two centuries, immigrants from England came to America for new economic opportunities and eventually for the freedoms promoted in the United States of America.

Matthew N.

I am not a traitor. I did not fight in the Revolutionary War for the Crown, but my great-great-great-great grandfather did fight for the Crown. In the following paragraphs, you will hear the story of Captain John Hatfield and my other British ancestors.

John Hatfield was born in England in the 1740s. He traveled to America around 1774 and married Mary Lockerman on June 28, 1778 in Trinity Church, New York City. He served with the British before the Revolutionary War and late in the Provincial Regiment of the Loyalist of New Jersey Π3rd New Jersey volunteers. On April 15, 1777, he was appointed captain. The reason that it was reasonable for him to fight in the British Army was because that was his culture.

If I had the opportunity to talk to Mr. Hatfield, I would say to him that he should fight for the American army instead of the loyalists because Britain is taxing the Americans without any representation in the British Parlaiment. Being taxed for another country's economic problems was not fair. At the end of the Revolutionary War, John Hatfield was unable to stay in America. After obtaining a land grant for 700 acres of land, he settled in Parrsboro, Canada. He died in 1804, having settled in Fox River, Nova Scotia. I don't think it was fair that John Hatfield was forced to leave America because I thought America was the land of the free. America is a country where people can choose when and where to do things as long as it doesn't break the law. Losing the war was punishment enough.

My great grandfather, Wallace Crane Gilbert, moved from Nova Scotia to Waterville, Maine, in 1920. He married a woman named Leona Pekie and moved to Boston, Massachusetts. When he moved to Boston, he put himself through school at Wentworth Institute and became a master plumber. He moved to America from Nova Scotia due to a lack of work in Canada. I think it was a good decision, because he was starting a good future for his children. My ancestors, the Hatfields, were in a very famous fight. It was called the Hatfield/McCoy feud. The Hatfields and the McCoys were neighbors who always competed and fought against one another. I think this was stupid, because they were fighting over small things. I really respect my British ancestors. They all traveled from Britain to America to Canada and back to America. It must have been very hard for them when no one in America welcomed them, and Canada did not have good job opportunities.

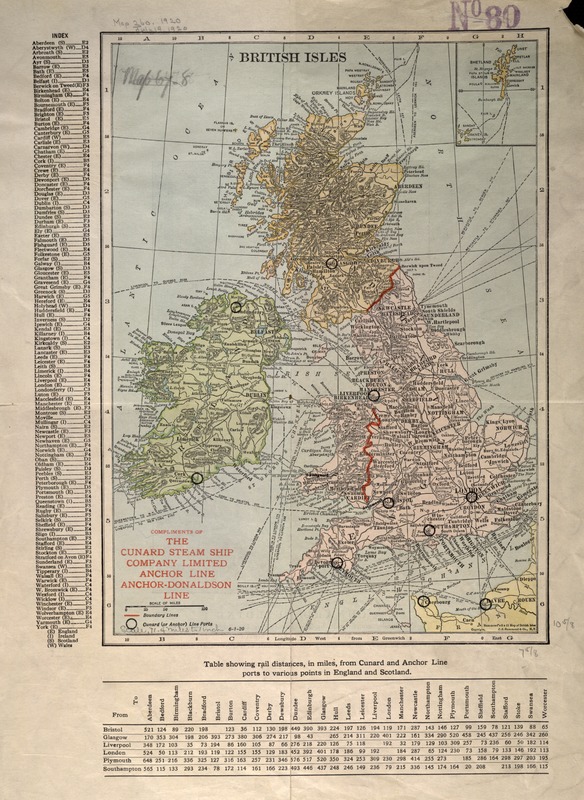

Cunard Steam Ship Co.

British Isles

New York, c. 1920

Published for the Cunard Steam Ship Company in the 1920s, this map locates the company’s ports in the British Isles. It also displays the various routes connecting these ports with each other and other ports in Europe and America.

Established in 1840 primarily as a mail line, by 1920 the Cunard Steam Ship Company was the premier trans-Atlantic cruise line, boasting among its fleet such famed vessels as the Brittania, the Mauritania, and the Lusitania (the latter of which was lost to a German U-boat in 1915). The Cunard line would later grow to include the Queen Elizabeth II, which still serves the trans-Atlantic route.

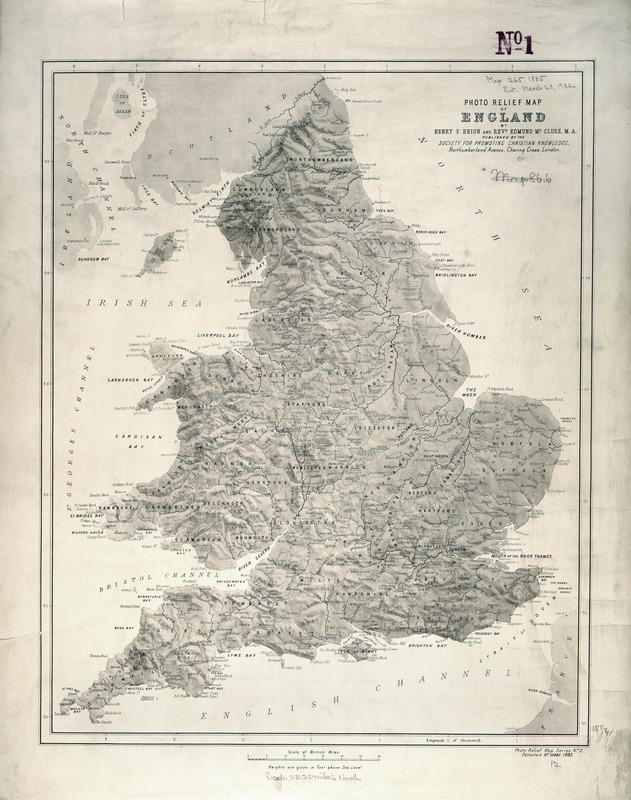

Henry F. Brion and Edmund McClure

Photo Relief Map of England

London, 1885

England’s physical geography, especially its topography and rivers, is portrayed on this late-19th-century map published by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, a British missionary and charitable organization. The Society was founded in 1698 and has been continuously active for over 300 years. In addition to their missionary and liturgical publications, the Society also published maps and atlases for the general education of its members. One such map is this physical relief map, which also displays the names of towns and counties, but does not delineate county boundaries.

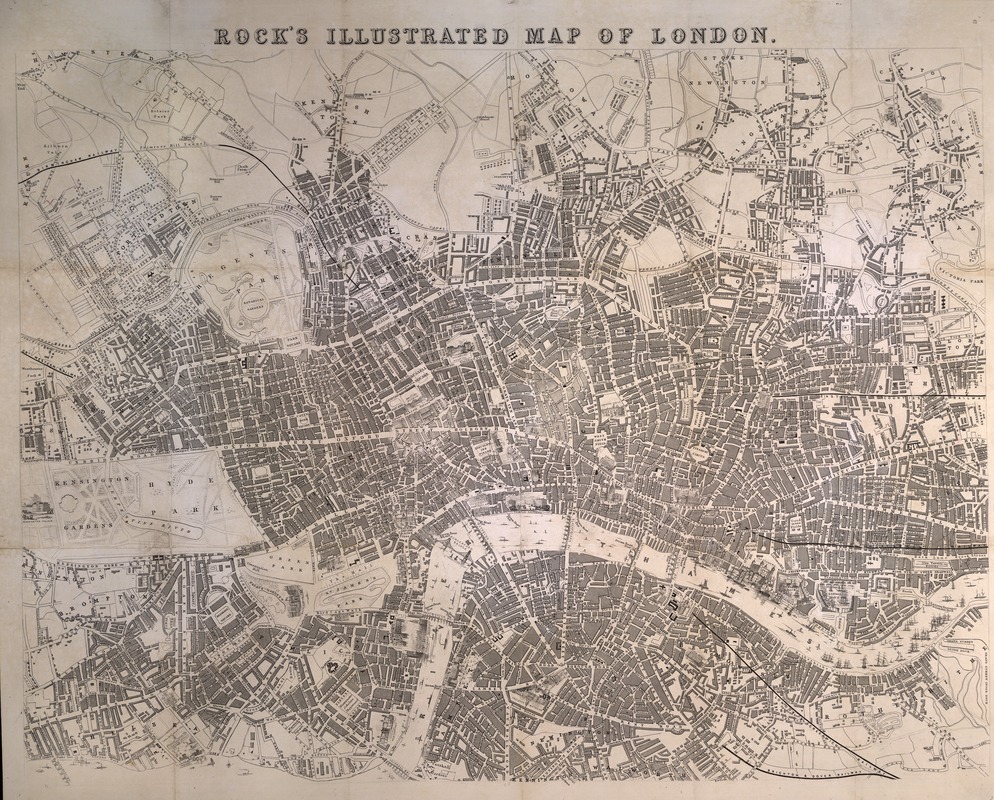

Rock and Co.

Rock’s Illustrated Map of London

London, c.1845

This inventive city map of London includes tiny facades of landmarks and prominent buildings such as Kensington Palace, Trafalgar Square, railway stations, wharfs, and the Houses of Parliament.

The map is undated, but its time frame can be deduced from several clues. Because the map shows the Hungerford Bridge, built in 1845, but not Waterloo Station, built in 1848, it must have been printed between these two dates.

Victorian London is laid out here in all its industrial triumph and tragedy. New steam railways (black solid lines) snake into the city from the edges of the map, while the orphanages, hospitals, and asylums, set aside for society's outcasts, are scattered throughout the city.

Anonymous

A New Most Accurate & Complete Map of all the Direct and the Principal Crossroads in England and Wales carefully corrected from late surveys with distances by the mile stones and the most exact admensurations between town and town

[London, c.1750]

This map is a mid-18th-century equivalent of a modern road map, showing the major roadways and distances in miles between towns in England and Wales. Latitude and longitude are not shown on this map. When navigating by horse and carriage or by foot, accuracy of mileage and general direction was all that was needed, as opposed to the precise co-ordinate placement that was so crucial for seafaring navigators.

Gerard Mercator (1512-1594)

West Morlandia, Lancastria, Cestria, Caernarvan, Denbigh, Flint, Merionidh, Montgomery, Salopia, cum insulis Mania et Anglesey

Amsterdam, 1628 or 1633

Gerard Mercator (1512-1594)

Cornubia, Devonia, Somersetus, Dorcestria, Wiltonia, Glocestria, Monumetha, Glamorgan, Caermarden, Penbrok, Cardigan, Radnor, Breknoke, Herefordia, & Wigornia

Amsterdam, 1628 or 1633

These two maps, portraying portions of Cornwall and Wales, were originally prepared by Gerard Mercator, one of the greatest of early Dutch map makers. These two atlas sheets were published in either the 1628 or 1633 French edition of Mercator and Jodocus Hondius’s Atlas. Originally published in 1595, this book of maps was the first such publication to use the term “atlas” to describe a collection of published maps. The use of this term is often associated with the Greek Titan, Atlas, who was condemned by Zeus to carry the heavens and earth on his shoulders for all time.

James Wyld (1812-1887)

Map of the Superficial Geology of the British Isle, with the physical and topographical features ...

London, 1843

Despite the title’s suggestion that this is a geological map, it is much more. It not only shows the standard cartographical features, such as roads, railroads and stations, canals, steamboat passages, towns, cities, counties, and distances for all of the British Isles, it is also an electoral map, as it indicates the number of parliamentary seats for each borough.

Electoral representation was a topic of particular importance in early- and mid-19th century Britain. Population decline in many formerly important centers combined with the implementation of representation policies that were hundreds of years old meant that many towns and villages with only a few dozen residents or even less, had the right to elect members of the House of Commons. Newer industrial centers such as Manchester, meanwhile had no representation at all. The electoral reforms of 1832 revised this system to provide at least nominally equitable representation.

By including this electoral data, the map maker, James Wyld, the younger (1812-1887), added a human element to the otherwise purely structural elements of the maps – it is a map of Brits as well as of Britain.

Thomas Kitchin (1719-1784)

England and Wales Accurately Delineated from the latest Surveys

London, 1783

England’s geography at the close of the American Revolution is portrayed on this map by Thomas Kitchen, hydrographer to the British King. Administratively, the country was divided into shires or counties, the names of which were often transplanted to towns and counties in British North America. According to the legend, there was also a well-ordered hierarchy of urban settlements, identified as cities, county towns, boroughs, market towns, and villages.

The importance of London as the country’s administrative and financial center is evidenced by the numbers placed alongside many town names, indicating the distance from that town to London. To assist in locating these places, the map also has a well-marked grid of longitude and latitude.

On this map, longitude is measured east or west from London, using a north-south line or prime meridian running through the Greenwich observatory outside London. By the end of the 19th century, the Greenwich Prime Meridian was accepted as the international standard. Prior to that time various prime meridians were used by different cartographers.

Ireland

Many Irish immigrants arrived in Boston during the first half of the 19th century. In 1803, the Act of Union joined Anglican-controlled England with Catholic-dominated Ireland. Many Irish, fearing the political repercussions of a union that left England in control, fled to the United States and particularly to Boston. A decade later the infamous Potato Famine swept through the island nation and brought a second wave of Irish immigrants to Boston.

Michael L.

Good day. Mo Chairde. Which means, "Hello, my friends." My name is Michael, and as you can tell, my heritage is Irish. The language that most of the Irish speak is Gaelic. But it is rarely heard, so no one really uses it any more. Some words like gille, which means boy, and Iain, which means John, are some Gaelic words. My mother's grandmother came from Ireland and moved to Roxbury. After that, she moved to West 7th Street in South Boston. When my mother and siblings were growing up, she moved them to the Old Colony Projects. After she died, my mother and her siblings broke up and moved around South Boston and Roslindale.

My mother met my dad when she was 37 years old. Then in two years they had me, the best Irish son. When I was born, my features were pail white skin, with bright reddish hair -- what almost every Irish person looks like.

I grew up in a neighborhood where there are no Irish families, and most families are African-American. Nevertheless, I have learned that back in the 1800s, families in Ireland moved to the U.S. and Australia because of the potato famine. There are many more Irish people in the United States than there are in Ireland.

In Boston, there is an Irish festival where Irish men and women get together and celebrate a holy day. That holiday we call St. Patrick's Day. It is a time of celebration where my family comes together for a huge feast.

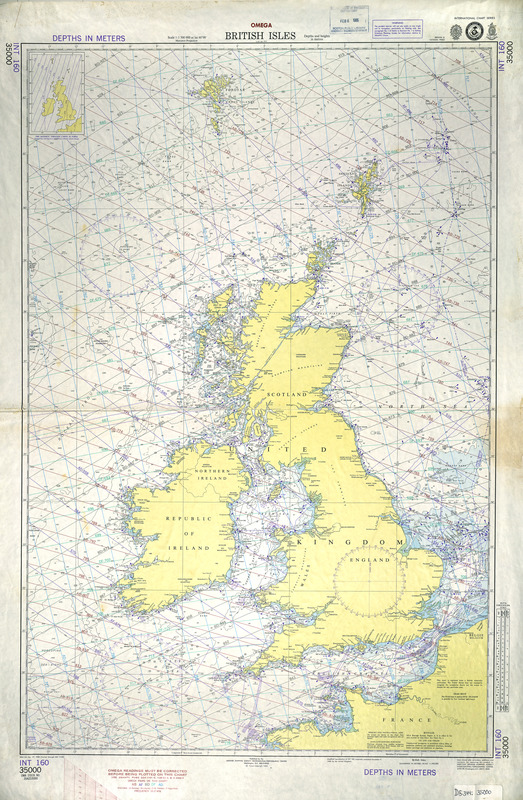

U.S. Defense Mapping Agency

International Chart Series, British Isles, Omega

Washington D.C., 1985

This navigational chart is the modern version of a late Middle Ages portolan chart, giving directional headings and detailed depth soundings to aid in seafaring navigation.

This modern chart serves as a reminder that England is an island nation off the coast of Europe and that seafaring was an important activity in its history, especially since the late 16th century. Through its maritime and trading activities, England built a colonial empire around the world that included portions of North America and the Caribbean. As a modern navigational aid, this chart focuses on depth soundings in the coastal areas and surrounding seas, while the interior areas of the British Isles are left relatively blank, in stark contrast to modern tourist maps of Britain

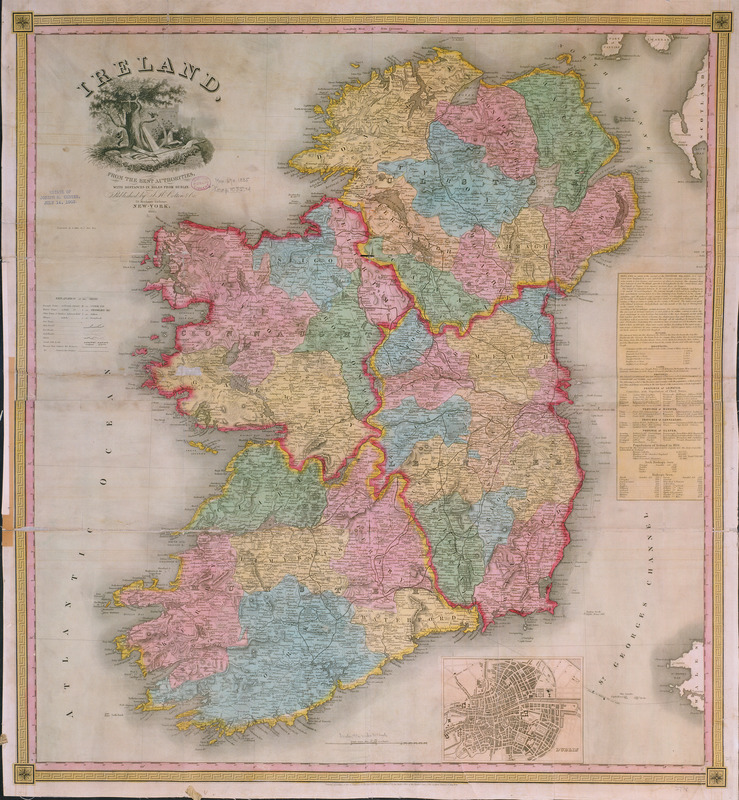

Joseph H. Colton (1800-1893)

Ireland, from the Best Authorities, with distances in miles from Dublin

New York, 1835

Published by one of America’s leading atlas publishers ten years before Ireland’s potato famine, this map depicts a country blossoming with population growth and urban development. A sidebar lists the population of the major towns in each province. Dublin was, by far, the most populous city, with over 250,000 residents, while the second largest, Limerick, was only one quarter of Dublin’s size. The total population of Ireland at this point was nearly eight million.

There is no evidence on this map of the famine which struck in 1845. By 1851, the population had been reduced by two million due to a combination of starvation, disease, and immigration.

I.G.L Weidner (active 1804-1811)

Charte der vereinigten Kongreiche Grosbritanien und Ireland nach den neuesten Berichtigungen und astronomischen Onsbestim[m]ungen entworfen auf der Sternwarte Seeberg, bey Gotha...

Weimar, 1804

Published by the Geographische Institut in Weimar, Germany, this map of Great Britain and Ireland shows extraordinary detail for such an early date. The coastal features, rivers, and towns were placed with a high degree of accuracy, attributed in part, as the caption says, to the "latest reports and astronomical observations." The insets identify the location of counties and provinces within England, Ireland, and Scotland. Longitude is measured east from Ferro.

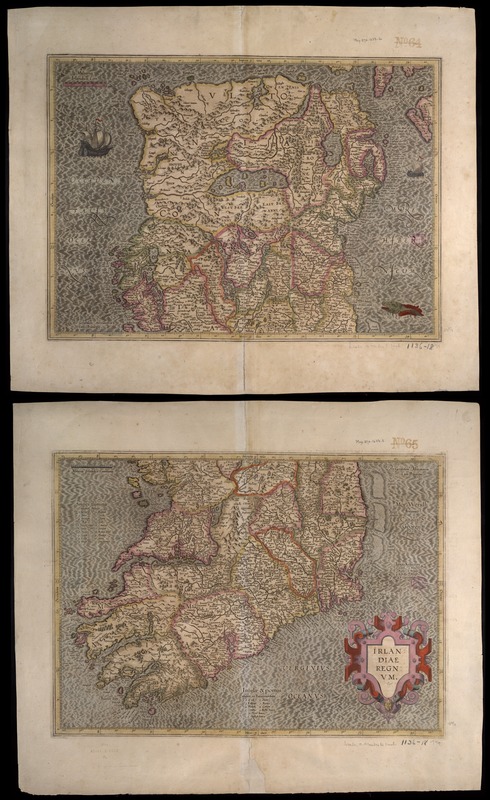

Gerard Mercator (1512-1594)

Irlandiae Regnum [Southern and Northern Ireland]

Amsterdam, 1628 or 1633

Together these two atlas sheets comprise Gerard Mercator’s map of Ireland. They were published in either the 1628 or 1633 French editions of Mercator and Jodocus Hondius’s Atlas. Originally published in 1595, this book of maps was the first such publication to use the term “atlas” for its title. As a cartographic triumph, the atlas was translated into the major European languages (Latin, French, German, and English) and was reprinted dozens of times up to the mid-17th century.

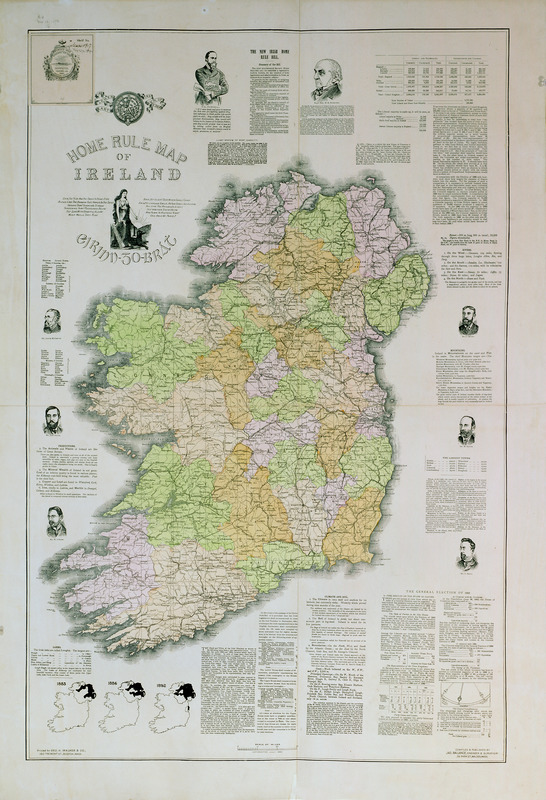

James Balance

Home Rule Map of Ireland

Boston, c. 1894

This highly political map was published in Boston for an audience of Irish immigrants eager to learn all there was to know about efforts to pass the Home Rule Bill in Ireland. This Bill was intended to give Ireland its own parliament.

Although the bill passed the British House of Commons in 1893, it was rejected by the House of Lords. The British Prime Minister W. E. Gladstone, who is pictured and quoted at the top of the map, resigned his post in protest. (A version of the Bill finally passed in 1914).

The text of the Bill is given in full at the top of the map, and men who supported it are pictured in the margins. Robert Emmett, who led a revolt against the English in 1803, is quoted along with nationalist leader C. S. Parnell. At the bottom of the map is a detailed analysis of the General Election and the political leanings of the newly elected Irish Members of Parliament. At the upper right is an electoral analysis of the election.

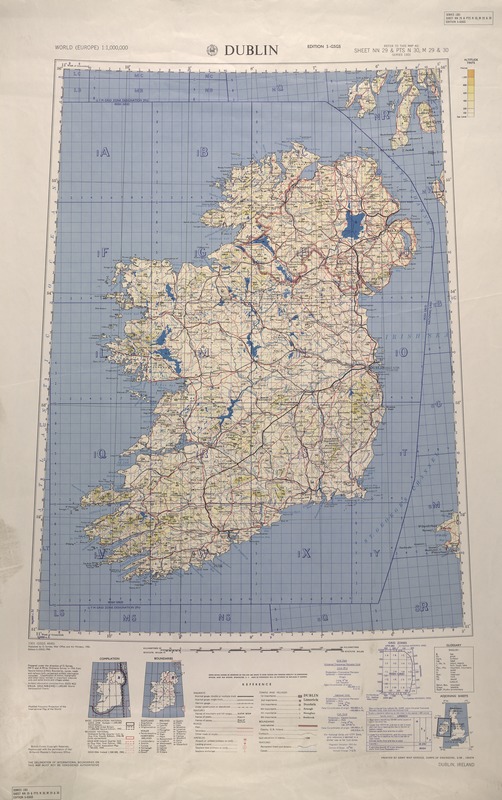

U.S. Army Map Service, Corps of Engineers

World (Europe), 1:1,000,000, Dublin

Washington, DC, 1956

Published by the U.S. Army Map Service, the map series of which this map of Ireland is a part, had its origins in an ambitious project called the International Map of the World. The idea, conceived by German geographer Albrecht Penck, was to create a series of 2,500 topographic map sheets that would cover the planet, all in the same scale of 1 centimeter equals 10 kilometers (or 1:1,000,000).

In 1913, an international conference established standards and practices for the project, giving each participating country responsibility for creating its own maps. Although the project was eventually taken over by the United Nations, funding and international enthusiasm soon waned. After World War II, several countries (including the United States and the United Kingdom) published their own world map series at a scale of 1:1,000,000.

Italy

The largest group of Italians came to Boston and America between the end of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century. During this period of great migration, most of the immigrants came from southern Italy. After the unification of Italy in 1861, under Victor Immanuel II, Italy began to industrialize. By 1878, at the start of the reign of Humbert I, the gap between the more industrialized north and the more rural agricultural south grew larger. A population explosion in the south prompted many southern Italians to migrate north to find jobs. Many also decided to immigrate to the United States. These southern Italians, accustomed to an agrarian economy, had to adjust to the new industrial urban lifestyle in Boston. A second wave of Italian families immigrated to the United States during the first half of the 20th century as many people tried to escape Mussolini, Fascism and two world wars.

M. Bianchi

My name is M. Bianchi. In English, Bianchi means White, but in Italian, it means something different. The reason why it means something different in Italian is because when they translated the word, Bianchi was not phrased correctly. The lesson is because the Italian language does not fit the English language vocabulary.

1923 was the year my great grandfather came to America. His name was Larry. He probably changed his real name to Larry so it would sound more American. My great grandfather went back to marry my great grandmother in Italy and bring her back to America with him. They moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Later on, they moved to Boston because they found out that relatives were living there.

My great grandfather lived on the outskirts of Rome in a city that is now dead. The reason why my great grandfather moved her was because the economy in Italy was not good and it was hard to get work. My great grandfather heard that America was a growing country and came to find work. About a year later, my great grandfather enlisted in the army. My grandfather was drafted into World War II. Don't think he was 100 years old, because this was the end of the war. He is still alive. He has gone through a lot. When he got older, he was a construction worker. Then he worked for the statehouse, fixing it and getting rid of rats. He met my grandmother and had three kids - one was my dad.

Now you know about the Bianchi family. I look up to my father, my grandfather, and my great grandfather. They've accomplished a lot living here.

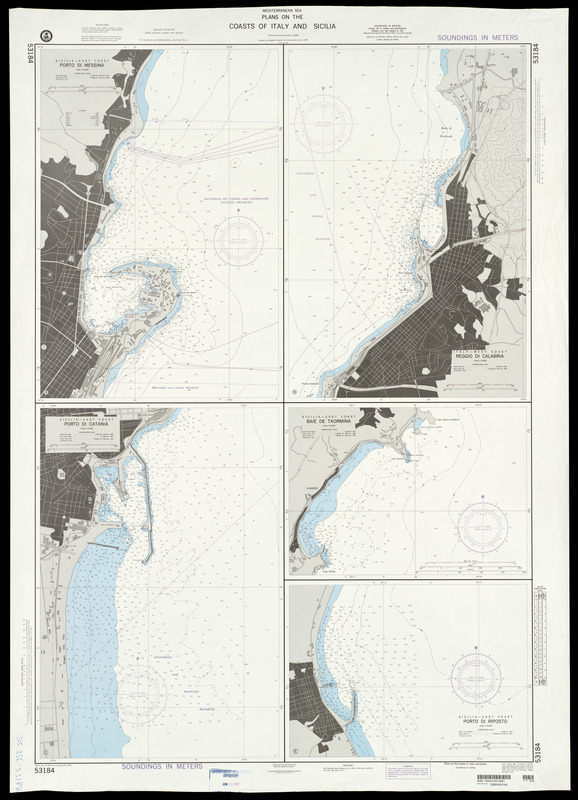

U. S. Defense Mapping Agency

Mediterranean Sea, Plans on the Coasts of Italy and Sicilia

Washington, D.C., 1996

This chart, part of the U.S. Department of Defense’s international hydrographic chart series, provides detailed soundings along portions of the Italian Mediterranean coastline. The five insets cover the ports of Messina, Calabria, Catania, Baie de Taormina, and Riposto, located on the island of Sicily and the west coast of Italy.

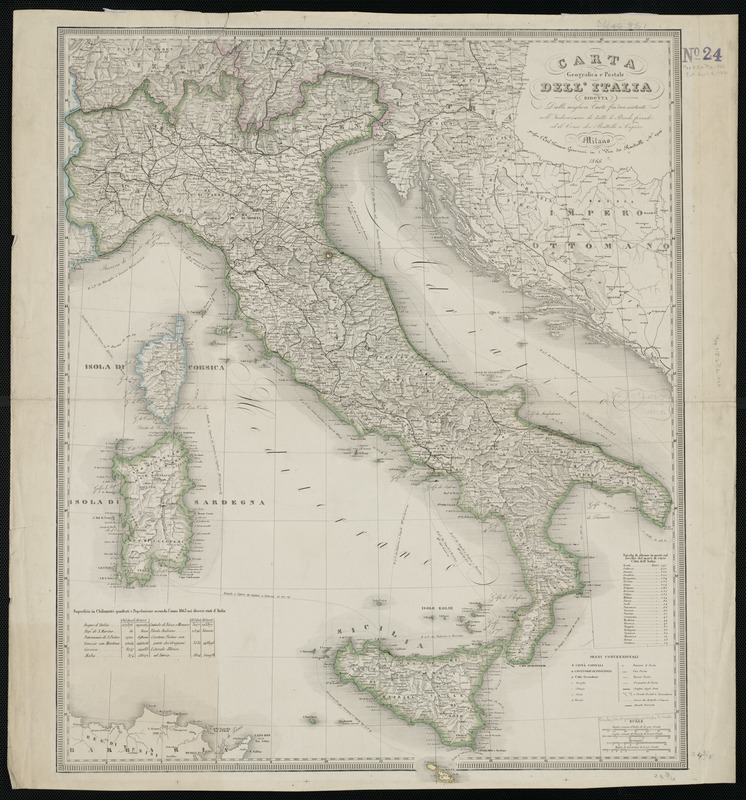

Tomaso Geneviesi

Carta geografica e postale dell’Italia...

Milan, 1866

The geography of Italy during the middle of the 19th century is depicted on this detailed postal map. I t not only portrays Italy’s mountainous topography by shaded relief, it also shows the location of post offices, postal routes, and railroads.

The table in the lower left corner of this map lists the population and area of various regions within Italy, including the tiny Republic of San Marino, seen as a small red circle in the north-central portion of the map. This region remains an autonomous republic today. The area of each region is given in square kilometers; by 1866, the metric system had been in use in Italy for nearly 20 years.

Also noted on this map are ferry routes between various cities in Italy, with distances and times of passage. A boat trip from Palermo to Naples would have taken 20 hours in 1866, while the same journey today takes nearly half the time.

Auguste-Henri Dufour (1798-1865) and Charles Dyonnet

Italie

Paris, 1857

This map shows, in extraordinary detail, the roads, waterways, cities, towns, and topography of mid-19th-century Italy. Just north of the Sicilian island of Pantellaria, a tiny and brief note mentions the mysterious volcanic island of Ferdinandea (a.k.a. Graham Island) that rose out of the sea in 1831 only to sink again a few months later. When the island emerged from the ocean, it was immediately claimed by the Italian and British governments each of whom, in turn, gave it a name. Recent seismic activity in Sicily has prompted speculation that the island may soon rise again, reviving the old territorial dispute.

Giuseppe Molini

Pianta della Citta di Firenze

Florence, 1847

The mid-19th century was a time of immense change in Florence and throughout Tuscany. This map was produced at the very end of the reign of the Dukes of Tuscany over the city of Florence. The splendor of the duchy is much in evidence here -- from the huge palace and extensive gardens of the Pitti Palace in the north to the imposing fortress of the Castello San Giovan Battista at the south. It was, in part, this very splendor and extravagance that inspired the brief popular revolution in 1849 in the wake of similar uprisings in France. Although many of the streets on this map are still found in today's Florence, the modern city extends far beyond the boundaries outlined here

Herman Moll (c.1654-1732)

A New Map of Italy Distinguishing all the Sovereignties in it...

London, 1714

This map could easily have been titled "A Disaster-lovers Guide to Italy," filled as it is with pictures and vivid descriptions of infestations, eruptions, and earthquakes.

Mt. Aetna is described as a mountain that "sometimes issues out pure flame, and at other times a thick smoke with ashes…streams of fire run down, with great quantities of burning stones, and [it] has made many great eruptions." Eruptions of Mts. Aeolius, Vesuvius, and Aetna are vividly depicted in the insets at the left.

The town of Syracuse ("Siracusa") on the island of Sicily is said to have been "almost entirely ruin'd" by the earthquake of January 11, 1693. In fact, the city was completely destroyed and thousands lost their lives.

Further north, Taranto is said to be the home of the tarantula, since the giant spiders "abound in the neighborhood, their sting is very dangerous, makes people weep, dance, tremble, vomit, laugh, faint and die if they are not relieved by musick which sets them dancing and dissipates the poison by the exercise." There was in fact a neurological disorder once prevalent in this part of Italy called "tarantism," which induced in the sufferer a kind of hysteria, including a sudden inclination to dance and spin -- the perspiration of dancing helped the body to heal itself. It was commonly thought, as expressed on this map, that the illness itself was brought on by the bite of the tarantula and that the dance was the cure. The Italian folkdance, the tarantella, originates from this folktale.

Nicolas Sanson (1600-1667)

Italia Antiqua …

Paris, c. 1650

Nicolas Sanson, one of the earliest of the great French cartographers, produced in addition to modern (contemporary) maps, a series of maps of the "ancient world," including this one of Italy under the Romans. Using texts both ancient and modern, Sanson reconstructed, as best he could, the roads, towns, and regions of "ancient" Italy.

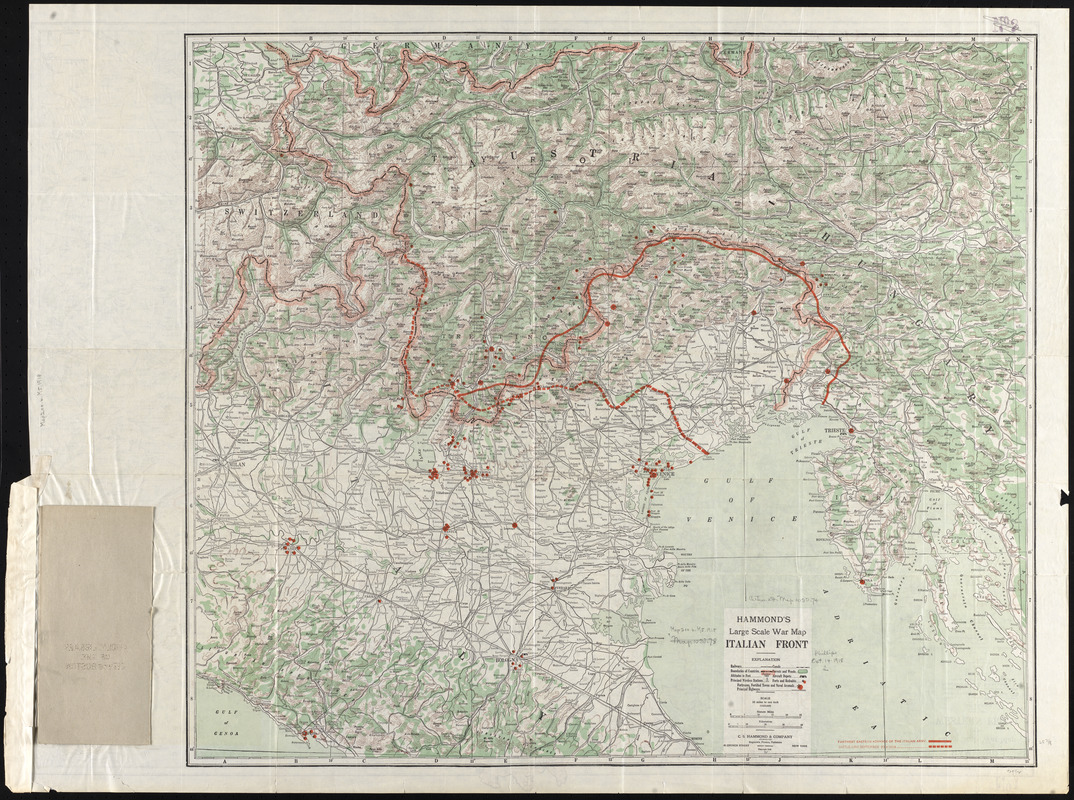

C.S. Hammond and Co.

Hammond's Large Scale War Map, Italian Front

New York, 1918

Published for an American audience, this war map depicts the Italian front during World War I. The Italian front lines depicted on this map represent the northern and eastern positions of the Italian army as of September 23, 1918. Only a month later, the Italian army pushed over the Piave River to take the contested town of Vittorio Veneto. The army continued to push eastward with a momentum that quickly led to the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian army. The cease-fire was called on the second of November, effectively bringing World War I to an end.

U.S. Central Intelligence Agency

Italy

Washington, D.C, 1973

This modern reference map provides much information about the topography, roads, and cities in Italy. It has several informational insets at the right showing population density, distribution of industry, and land use throughout the country. The circular inset at the upper right places Italy in a global context, and, immediately below, the superimposition of Italy on the southeastern United States gives the American viewer a sense of the size and extent of Italy.

Jamaica, Haiti & Dominican Republic

Like its Caribbean neighbors, the former British colony of Jamaica has had its share of political troubles. Jamaica, however, new truly saw the extreme political upheavals of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Instead, the island country suffered from devastation caused by two hurricanes during the 1980s which occurred during the an economic growth period. The storms not only destroyed homes and businesses, but severely impacted the island's growing economy as well. The depressed economy gave way to rising crime and civil disorder. Seeking better lives in another English-speaking country, many Jamaicans came to Boston.

Shanique S.

One love, one heart, come to Jamaica and feel all right. Whenever I think of this line from the song by Bob Marley, it reminds me of Jamaica and how much I miss it. My name is Shanique, and I am a Jamaican-American. My mother and her older sister moved to America in 1987, the same year I was born. In 1990, I moved to America to be with them. My family moved from Jamaica because in Jamaica, it is very hard to make a living. You can't make very much money and everybody puts you down. Life in Boston is different from life in my country, because no matter how hard you try to be successful in Jamaica, it will feel like you are going nowhere, like a big circle. My family moved to America to let all the hardship lift off their backs. We originated from Portmore, Jamaica, the most beautiful place I have ever been. It is because of its beauty that even though life in Jamaica is harder than it is here, it will always be my country. But beauty is not its only draw. I also love Jamaica because of the large amount of creativity and color you find there. Jamaicans are creative. They take music from other cultures, like the song by R. Kelly, "The Greatest," and create their own sound and make it their own. Also, they are amazing story-tellers. Some stories told in America come from the Jamaican culture; like "Itsy-Bitsy Spider" emerged from the Jamaican story "Nancy the Spider." And the national colors are symbolized in the dress and how people act. No one in Jamaica is ever dull. They are always bright and stand out. Another great aspect of Jamaica is its prime minister. I feel that the American president could learn a great deal from the Jamaican prime minister. His name is James Patterson, and he is a wonderful role model. He treats every one with respect. Also, he moves around and gets involved with the community. And he cares about the safety of the people on his island. I feel our president should be more involved with the communities in America. The Jamaican prime minister represents the heart of Jamaica. In conclusion, Jamaica will always be my country, because I love its beauty, its creativity, its color, and its heart. Even though it's harder to live in Jamaica than here, I will always miss it.

The early 1990s saw a wave of immigration from Caribbean countries, including Haiti. After the ousting in 1991 of Haiti's first democratically-elected president, Jean Betrand Aristide, the United States and the United Nations imposed trade and oil embargoes on the country in an effort to remove its military leadership. As the military controllers resisted international pressure, the embargoes become harsher. The combination of economic ruin and civil disorder created a situation where many people fled the country. Even after a 1994 amnesty returned Aristide to power, Haitians continued to immigrate to the United States due to ongoing political turmoil and a weakened economy.

MacCalvin R.

My parents moved to America at different times and for entirely different reasons. In 1980, my mother came to the United States with her parents to pursue a better life and because they felt that she needed more parental guidance during her teenage years. She lived with her father in New Rochelle, New York. My father also moved to America to pursue a better life but he arrived in 1982. He lived Brooklyn, New York with his brothers. My mother and father met in New York, got together and started the family that I am part of today. After a few years they moved to Boston and were able to bring the rest of my father's siblings to live with them. During the early 1980's Haiti was a very quiet country where people worked mostly in the farming industry. Farmers in Haiti were paid very low wages. From my family, I have leaned more about the Creole language - to the point that I am now able to conduct a conversation with a fluent speaker. I now think I am part of something special, something most people cannot claim. Being part of a Haitian family has given me a sense of what Haitians are all about and has made me proud of my native culture.

Besides geographically sharing the same island as neighboring Haiti, the Dominican Republic shares many of the political and economic woes of its sister country. During the 1960s and 1970s, a continuous cloud of political uncertainty spread throughout the country, highlighted by a civil war in 1965. the government stabilized somewhat in the early 1970s, but remained fragile. As in most cases, political trouble leads to economic hardship. The Dominican Republic was no exception. At the end of the 20th century, the political and economic situation in the country began to improve significantly. However, by then many Dominicans had immigrated to the United States and the Boston area to escape decades of turmoil.

Diana C.

Ser Dominicana es muy importante para mi! In this sentence I say, "Being Dominican is very important to me." The fact that I am so proud of being Dominican comes together as one with many parts, such as my family and my culture.

I have six people in my family. I have two sisters, my mom, my grandmother, and my dog (Huffy). There are many things I care about, the thing that they all have in common is that we are proud of who we are.

My sisters Stephanie and Denise are both ten years old. In October 1999, my sisters came home with a math assignment which they didn't understand. They asked me if I could help them, and I said "no", but then I saw they were having a hard time which made me feel bad so I decided to help them. I would always set a challenge for someone, but during their challenge I would help them solve their challenge or come to a conclusion.

My family bleeds red and blue blood, but not for the American flag, they bleed for our Dominican pride. My Dominican family! My family is from the Dominican Republic, to be exact, the city of Santo Domingo. Santo Domingo is the capitol of the Dominican Republic.

My grandmother decided to come to the United States for a better life and a better future. A few years passed and in 1983 my mother came to the United States. She also came here for a better future and to get a better education. My father did the same.

I was standing on the stage at the Dominican Festival, when I saw all of my Dominican people waving their flags and showing me their Dominican pride. People can see how proud I am of being Dominican. I speak Spanish to all my family, including my friends. I think I am really good at speaking Spanish. I speak Spanish because I love it, and being able to speak Spanish is a special ability.

The life in the Dominican Republic is nice because the weather is always warm, and when it rains, it's still warm and doesn't rain for the whole day. The life in the Dominican Republic is exciting, because no matter what time it is or what the weather is, you can still go outside and have a good time.

Whether or not I am speaking to my family or even 200 people whether I am in an interview at a job, or speaking with my friends, they can notice how proud I am to be Dominican. People I chill with know that being Dominican flows through my blood. Y que viva la Republica Dominicana!

U. S. Defense Mapping Agency

International Chart Series, North Atlantic Ocean, West Indies

Washington. D.C., 1979 (1993)

Using the latest advances in modern technology for gathering depth soundings and generating automated cartography, this chart was prepared primarily for navigational purposes, testifying to sailors' continual quest for obtaining the most reliable information since the 16th century for navigating the treacherous waters of the Caribbean. It not only displays an extensive number of depth soundings throughout the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, but it also displays undersea contour lines suggesting the topography of the ocean floor. The shallowest areas, adjacent to the islands and mainland, are colored blue emphasizing waters that should be traversed cautiously.

In contrast to the colonial maps published from the 17th to 19th centuries, this modern chart demonstrates that by the end of the 20th century, none of the West Indian islands or the mainland territories remained colonial possessions. Most are now independent countries, while a few are self-governing administrative units of the original mother countries.

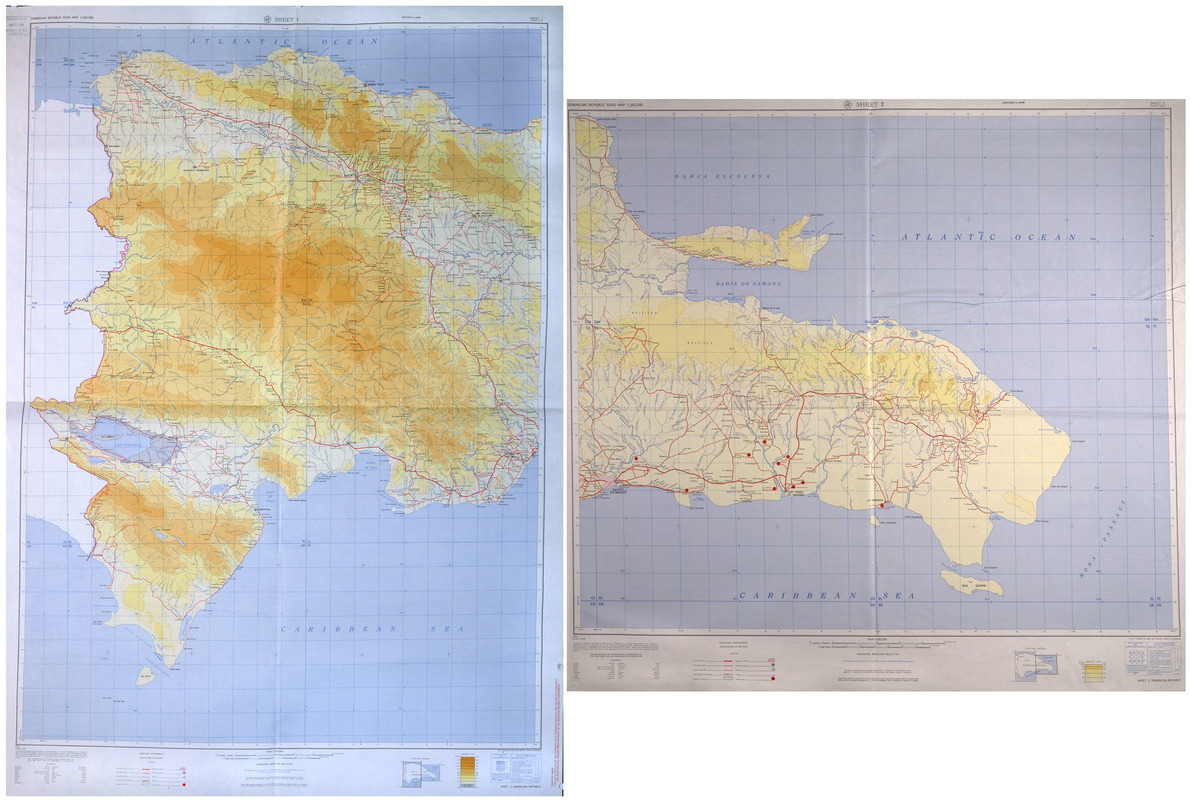

U.S, Army Map Service, Army Corps of Engineers,

Dominican Republic Road Map, 1;250,000, Sheets 1 and 2

Washington D.C., 1961

Together, these two sheets to make a topographical and road map of the entire country of the Dominican Republic, which occupies the eastern portion of the island of Hispaniola. The early 1960s was a time of extreme turbulence and violence in the Dominican Republic. The long-term dictator Raphael Trujillo had recently been assassinated, and the nation was in turmoil following a coup d'etat that removed his successor from power. Although this map appears to be completely neutral, offering just geographical facts, its publication most certainly reflected the United States military’s interest in maintaining stability in the Caribbean region.

U.S. National Imagery and Mapping Agency

Tactical Pilotage Chart (TPC J-26C), Cuba, Haiti, Jamaica, Navassa Island

Bethesda, MD, 1997

This map, designed for use by air pilots, was printed by the military mapping agency, formerly known as the U.S. Defense Mapping Agency under its current name the National Imagery and Mapping Agency. As indicated by the marked-off "special use" airspace over Cuba and the U.S. Naval Base at Guantánamo Bay, this particular region of the Caribbean can be especially complicated for flight navigation to and from the United States.

Navassa Island, located in the waters between Jamaica and Haiti was originally claimed in 1857 by the United States for mining operations. Since 1998, it has been recognized as an important oasis of Caribbean biodiversity and is protected as a National Wildlife Refuge.

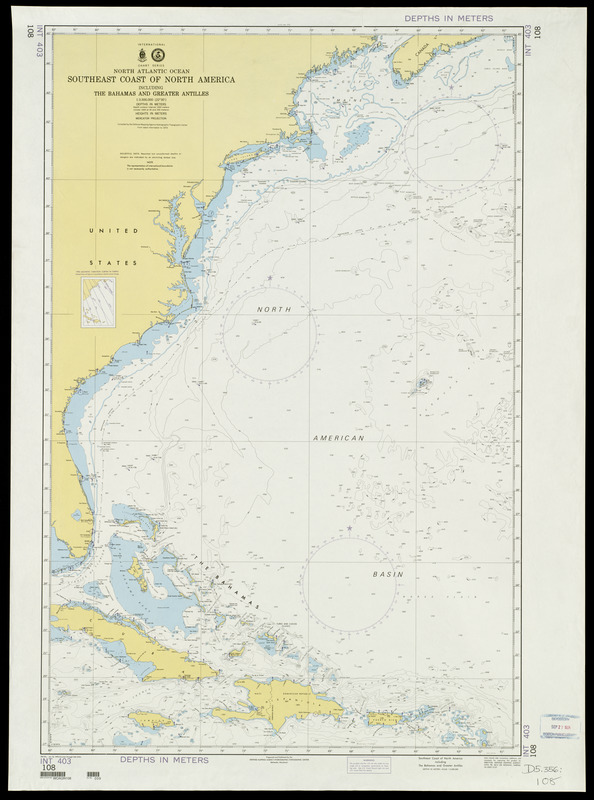

U.S. Defense Mapping Agency

International Chart Series, North Atlantic Ocean, Southeast Coast of North America...

Washington D.C., 1994

This navigational chart, which is one sheet in the U.S. Defense Mapping Agency’s world hydrographic chart series, shows the waters along the southeastern coast of the United States. In this part of the Atlantic Ocean, there is a warm ocean current, known as the Gulf Stream, which flows north from the Caribbean Sea along the east coast of the United States across the North Atlantic to Europe. Historically, the current provided the major route for European ships, especially Spanish galleons, returning from their Central American, Mexican, and West Indian colonies to Europe.

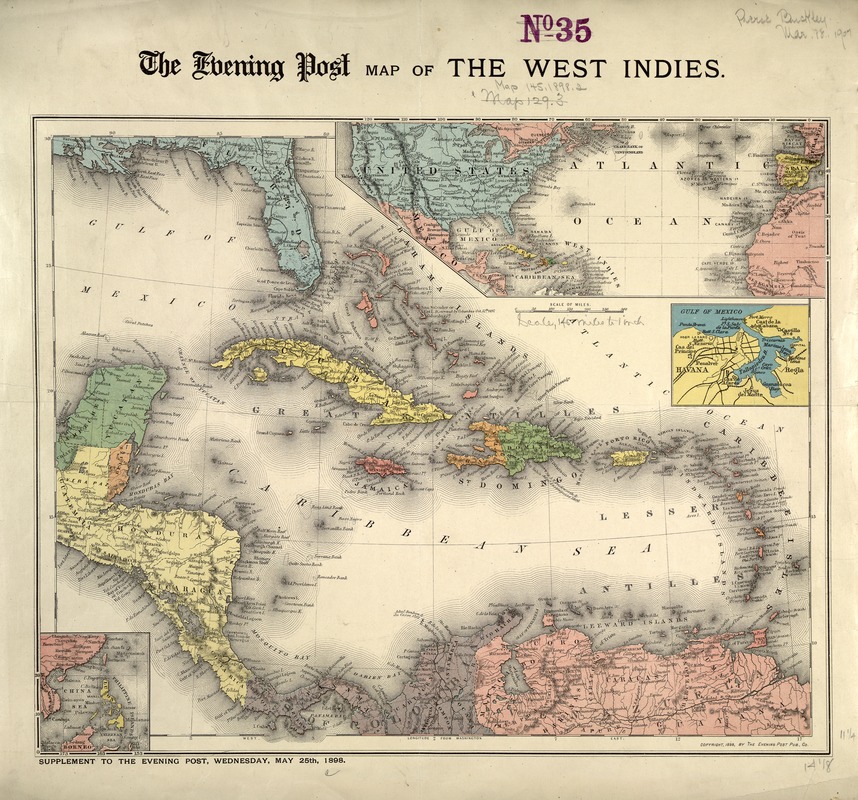

The Evening Post Publishing Co.

The Evening Post Map of the West Indies

New York, 25 May 1898

Printed during the Spanish-American War as a supplement to The Evening Post, this map is good example of journalistic cartography. Its purpose was to educate the newspapers’ readers and help them follow the course of the war just as modern newspapers publish maps and inserts to illustrate events of national and international interest. The insets of Havana and the Philippines may seem out of place, but are in fact quite timely; in May 1898, the United States was simultaneously sending troops to the Philippines and preparing for war with Cuba, both under Spanish control. With the United States undertaking territorial expansion in several parts of the world in 1898, this map would have been an indispensable guide for the American public to keep track of international developments.

Emmanuel Bowen (c.1720-1767)

A New and Accurate Chart of the West Indies with the Adjacent Coasts of North and South America

London, 1748

This chart was published in John Harris's Navigantium atque Itinerantium Bibliotheca, or A Complete Collection of Voyages and Travels. Although the chart also includes the eastern coast of the Americas, its main function was to aid in the navigation through the Caribbean Sea and around the West Indian islands.

Currents were indicated by arrows and deeper waters by darker shading. The text scattered throughout the map is primarily historical in nature, mentioning, for example, Columbus' landing in San Salvador, and the British annexation of the Bahamas in 1707. Navigational advice was also provided, as well as a detailed description of how to carry cargo overland across Central America from "the South Sea" (the Pacific) to the "North Sea" (the Caribbean) and back to London. "Inconveniences" along the trade routes included rough trade winds and pirates.

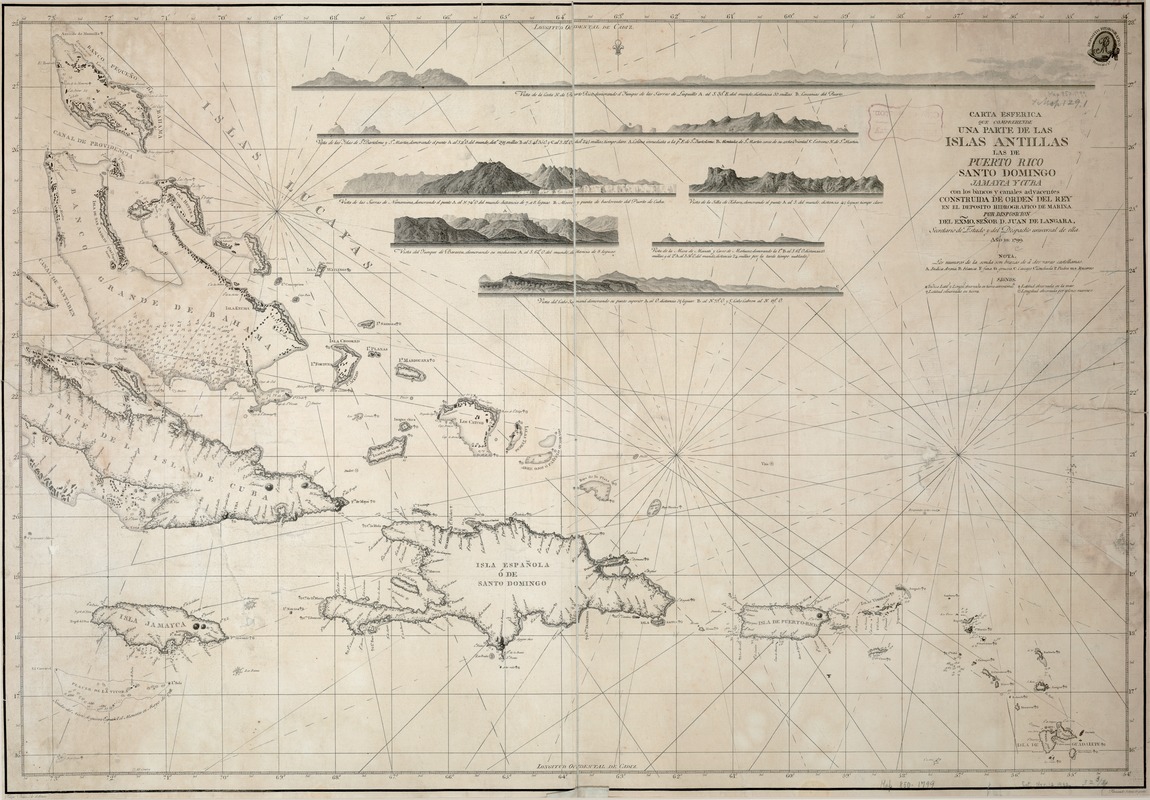

Felipe Bauza and Fernando Selma

Carta Esferica que Comprehende una Parte de las Islas Antillas, las de Puerto Rico, Santo Domingo, Jamayca y Cuba . . .

[Madrid], 1799

Cuba, Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico, the focus of Spanish colonial interest in the West Indies, are depicted on this 1799 nautical chart of the Greater Antilles, published by the Spanish Hydrographic Office. It is based on information provided by Spanish admiral Juan de Langara, who participated in several battles for possession of the islands. At the top, there are seven headland views, provided to assist sailors in easily recognizing island and harbor coast lines.

The legend also notes how latitude and longitude were computed for various sites. During this period, computation of longitude had not been perfected, and the east-west position of a ship was calculated using a variety of methods including astronomical observations (comparison of the time on ship of a predictable astronomical event with the time it would have been visible at a prime meridian) and maritime clocks (the use of two clocks, one set to local time each day at noon, and one set to the time at a prime meridian). In this case the prime meridian, the point from which longitude was measured, was Cadiz.

Didier Robert du Vaugondy (1723-786)

Les Grandes et Petites Isles Antilles, et Les Isles Lucayes avec La Mer du Nord

Venice, 1779

This late-18th-century map, which was based on earlier works by the French royal geographer, Robert de Vaugondy, depicts the West Indies, the chain of islands enclosing the Caribbean Sea. Stretching in an arc from southern Florida to the northern coast of South America, these islands have been divided into three groupings by geographers -- the Bahamas (Lucayas), low lying islands east of Florida; the Greater Antilles, including the large mountainous islands of Cuba, Hispaniola, Jamaica, and Puerto Rico; and the Lesser Antilles or Caribbees, small volcanic islands bordering the Caribbean Sea on the east.

In comparison to the rest of the Americas, the West Indies were not large in territory, but they were some of Europe's most prized possessions during the 18th century, primarily because of their ability to produce sugar and other tropical plantation crops. In the context of these intense political and commercial rivalries, Robert du Vaugondy placed the most prosperous French colony of Saint Domingue (Hispaniola) in the center of the map. He also identified the small islands in the Lesser Antilles with the letters "F", "A", and "D" to indicate French, English, or Danish control.

Although the border between Haiti and the Dominican Republic on the island of Hispaniola was officially drawn two years before this map was published, the map shows no such national boundary. This is almost certainly due to the fact that this map comes from an Italian reprint of Robert de Vaugondy’s Atlas Universel, first published in 1750-57, before the border existed.

Edme Mentelle (1730-1815) and Pierre Grégoire Chanlaire (1758-1817)

Carte des Isles de la Jamaique et de St Domingue

Paris, c. 1800

The eastern part of Cuba and the islands of Jamaica and Hispaniola are depicted on this map which appeared in the French school atlas, Atlas Universel de Geographic Physique et Politique. The atlas was published in several editions at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

The political situation on the islands of Jamaica and Hispaniola during this time period is evident here. By the end of the 18th century, British colonialism had imposed on Jamaica rather ill-fitting and contrived English-style counties with names such as Middlesex and Surry, names that are still used today. On Hispaniola, meanwhile, the Treaty of 1777 had given birth to the border between present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic. This separation is clearly delineated on this map.

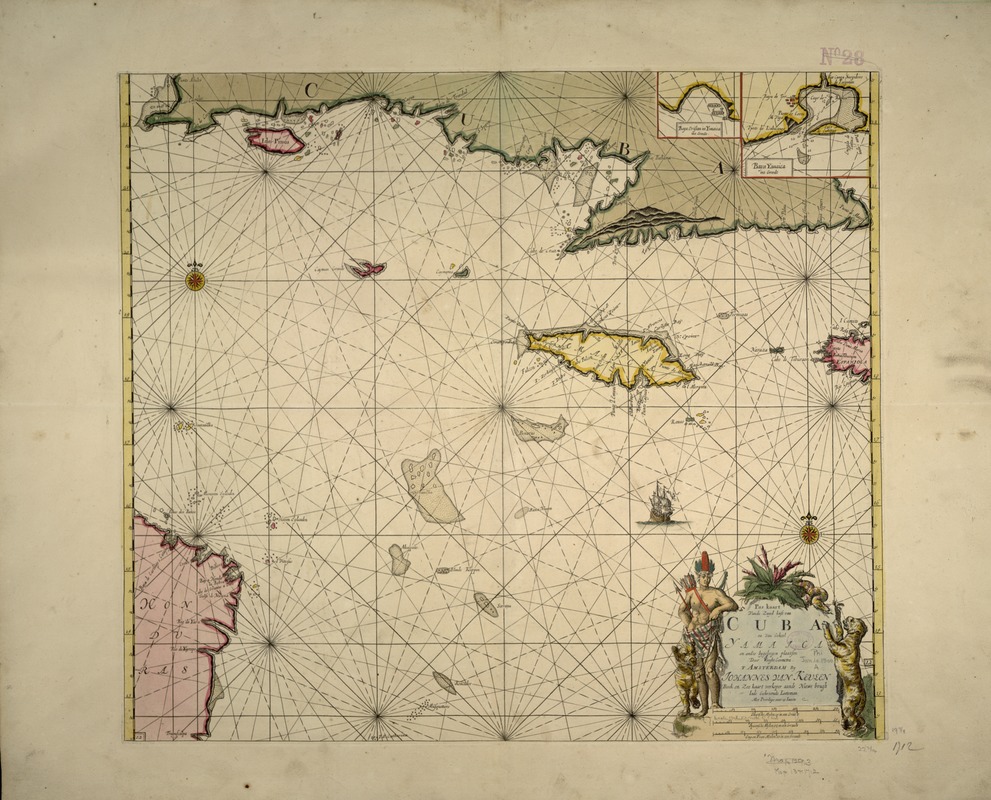

Gerardus Mercator (1512-1594) and Jodocus Hondius (1563-1612)

. . . Cuba, Hispaniola, Jamaica, S. Ioannis ende Margarita

Amsterdam, 1630

In this composite map of five West Indian islands, separate maps of Cuba and Hispaniola are flanked on the left by insets of Jamaica, Puerto Rico (here called the island of St. John), St. Margaret (north of Puerto Rico), and the port of Havana at the upper right. These early maps of Cuba and Hispaniola are covered with indigenous Taino place names. In addition to the Spanish name, the native names of Haity and Quisqueia are used for Hispaniola, and Taino place names such as Xaragua and Yaguana are used alongside Spanish names.

Eventually, the Taino settlements disappeared and their names were permanently replaced by Spanish and French names. This map is found in the 1630 Dutch edition of the Mercator and Hondius Atlas Minor issued by Jan Jansson. First published in 1607, this small-format atlas was based on Mercator’s larger folio atlas, entitled simply “Atlas” originally published in 1595. This was the first time that the title “Atlas” was applied to a book of maps.

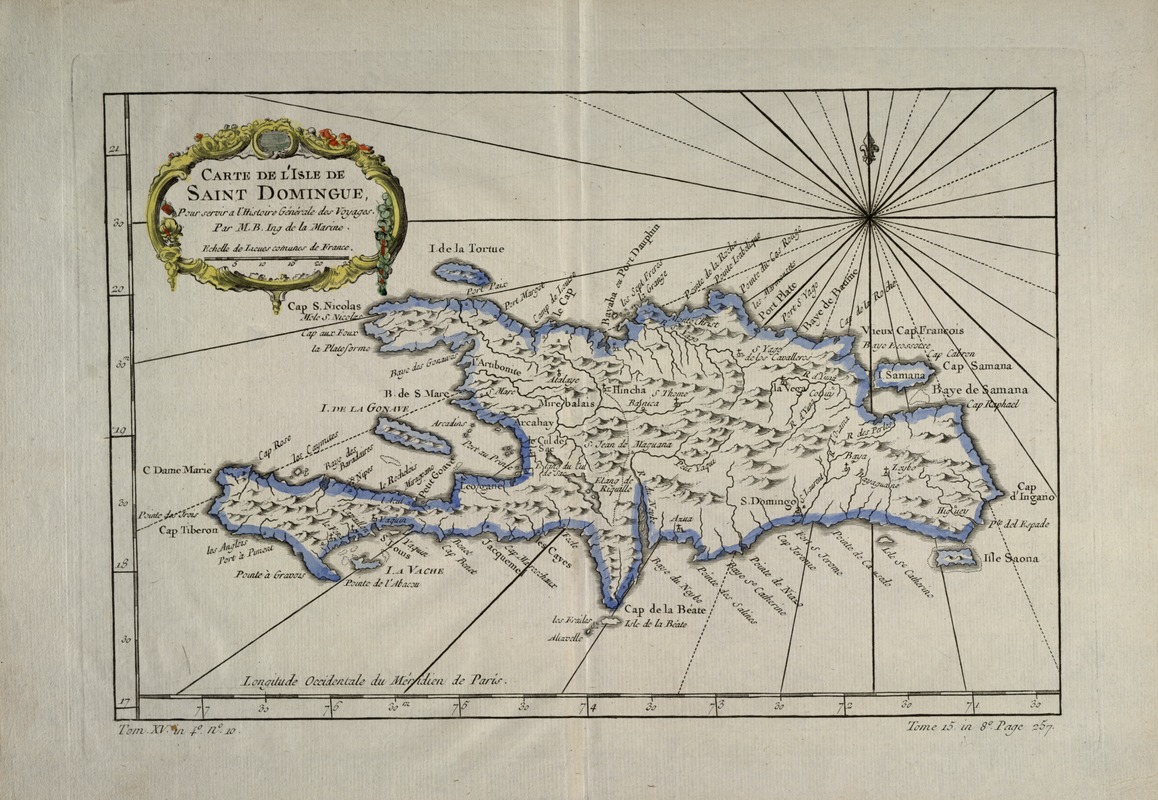

Jacques Nicolas Bellin (1703-1772)

Carte de l’Isle de Saint Domingue pour servir a l’Histoire Generale des Voyages...

Paris, c. 1750

Although no border between French and Spanish territory is indicated on this map (no official border existed until 1777), the uneasy sharing of the island of Hispaniola, or Santo Domingo, by the French and the Spanish colonial governments is evident in the island's place names. In the east, today's Dominican Republic, French names are used for coastal features, while the Spanish names used today are given for towns and churches. In the west, only French names are used. By the time this map was printed, the Spanish had ceded the western third of the island to the French. Spain would soon regret the concession, since what would later be known as Haiti was showing great promise in the sugar trade.

This topographical map of Santo Domingo features mountains and rivers in addition to coastal features and towns. It was published in volume 15 of A. F. Prevost's Histoires Generale des Voyages. Longitude is measured west from Paris, and the scale is given in standard French units.

Since this map was engraved during a period of strong colonialism on the island, and the original inhabitants were nearly extinct due to war and disease, there is little sign of the original Taino place names -- one remaining example is the Yaqui River near the center of the island.

John Thomson

West India Islands: Porto Rico and Virgin Isles; Haiti, Hispaniola or S. Domingo

Edinburgh, 1817

This combination map of Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and Hispaniola was published in the 1817 edition of Thomson's New General Atlas. Although by this time Puerto Rico and the eastern half of Hispaniola were both firmly in the hands of the Spanish, the Taino words for the big islands are given alongside their Spanish names -- "Boiiqua” and "Haiti." These maps are primarily topographical, recording very few human settlements, but mountains, rivers, inlets, bays, capes, and other coastal features are recorded in detail.

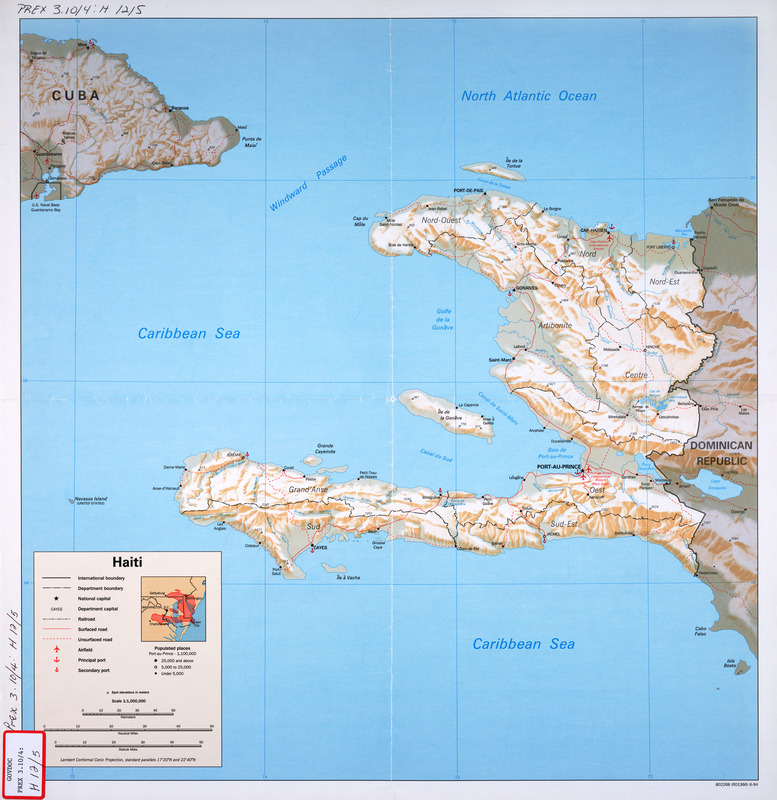

U.S. Central Intelligence Agency

Haiti

Washington, D.C., 1994

Modern-day Haiti is depicted on this general reference map published by the Central Intelligence Agency. Shading highlights its mountainous topography, while an inset map demonstrates that Haiti is about the size of Maryland and Delaware.

Although Haiti was the first Latin American republic to declare its independence, the population did not prosper. Throughout the 19th and 20th century, the country has been plagued by political turmoil and has been ruled by numerous dictators. Today, it is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, with many citizens seeking asylum in the Untied States, especially southern Florida. Haiti's neighbor to the east is the Dominican Republic, the former Spanish colony of Santo Domingo (Hispaniola), which gained its independence in 1844.

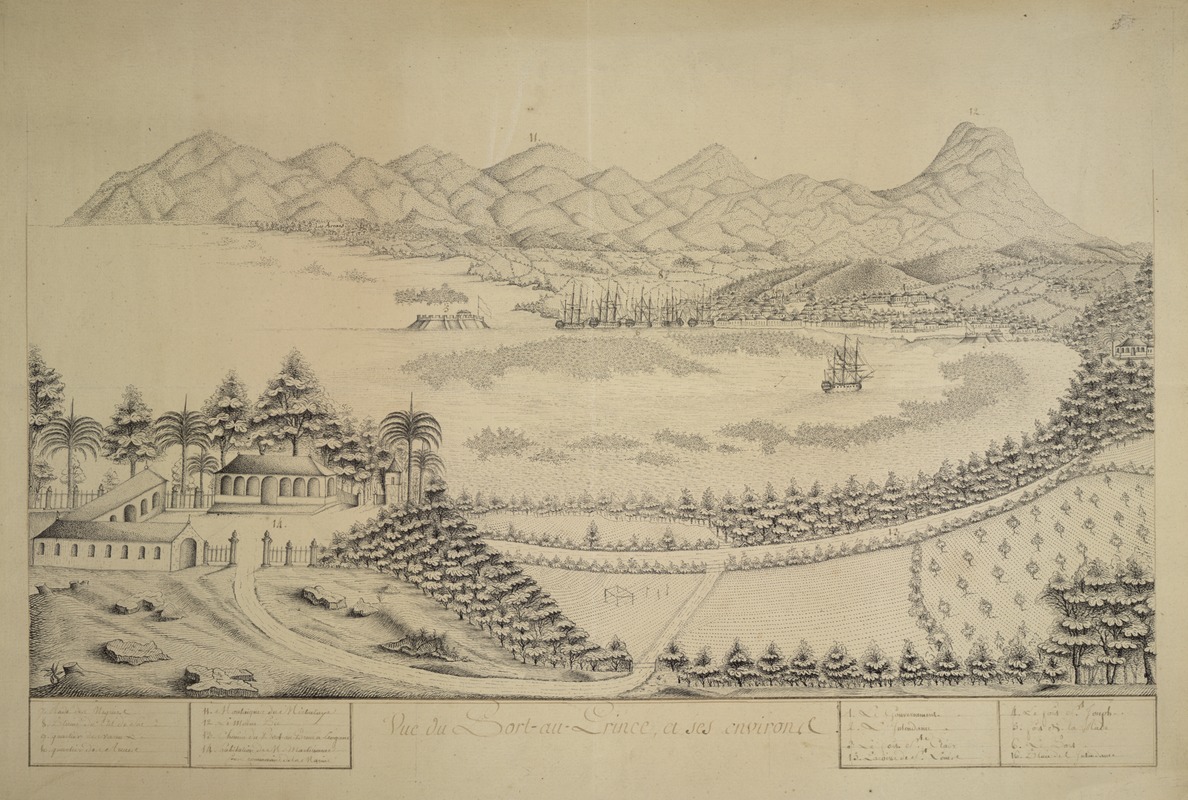

Anonymous

Vue du Port-au-Prince et ses environs

c.1800