Introduction

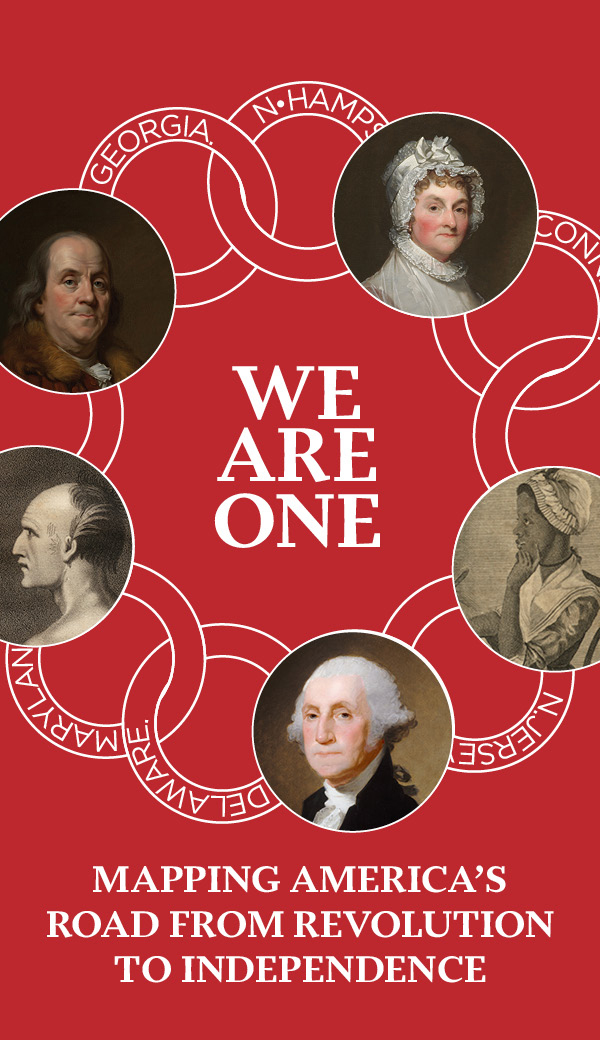

We Are One maps the American road to independence. It explores the tumultuous events that led thirteen colonies to join to forge a new nation. The exhibition takes its title from Benjamin Franklin’s early design for a note of American currency containing the phrase “We Are One.” This presaged the “E Pluribus Unum” found on the seal of the United States, adopted in 1782, and on all U.S. coins.

Using geographic and cartographic perspectives, the exhibition traces the American story from the strife of the French and Indian War to the creation of a new national government and the founding of Washington, D.C. as its home. Exhibited maps and graphics show America’s early status as a British possession: thirteen colonies in a larger trans-Atlantic empire. During and after the French and Indian War, protection of those thirteen colonies exhausted Britain economically and politically, and led Parliament to pass unpopular taxes and restrictions on her American colonial subjects. The Stamp Act, the Tea Act, and limits on colonial trade and industry incited protests and riots in Boston, as contemporaneous portrayals in the exhibition show.

When tensions between Britain and her American colonies erupted into war, British cartographers and other witnesses depicted military campaigns, battles, and their settings. These maps, drawings, and military artifacts now bring the long, bloody struggle for independence to life.

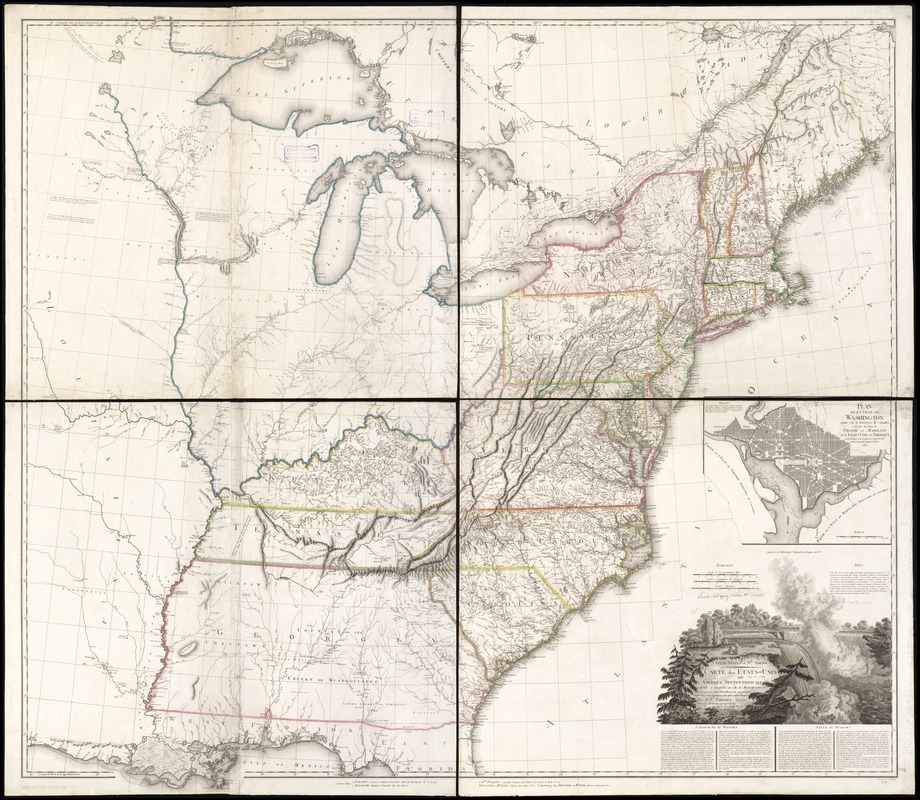

Finally, We Are One shows how, in the aftermath of the Revolution, America took stock of her new geography with surveys and maps. During this period, the Founders struggled to craft a new national government that would confederate thirteen colonies with different economic interests and cultures. European maps reflect their success by recognizing America’s triumphant new status of nationhood and her expanding territory.

TRAVEL SCHEDULE

Boston Public Library - May 2 to November 29, 2015

Colonial Williamsburg - March 6, 2016 through January 29, 2017

New-York Historical Society - November 2017 through March 2018

1 Prelude to the Rebellion

2015 marks the 250th anniversary of the 1765 Stamp Act, passed by the British Parliament to raise funds to pay for the French and Indian War (1754-1763). The act taxed printed material and spurred protests in many colonies. These new taxes undermined colonial prosperity and created a tense environment in Boston. This section of the exhibit highlights several significant events — the Stamp Act, the Boston Massacre, and the Tea Party — that occurred in Boston during the ten-year prelude to the Revolutionary War.

During the 1760s, Boston’s population barely exceeded 15,000, making it a small town compared to London, but the third largest port city in America. Boston’s waterfront bustled with the trade of goods, ideas, and enslaved people. The livelihoods of many Bostonians—from sailors and rope makers to shopkeepers and their families—depended on the health of the port.

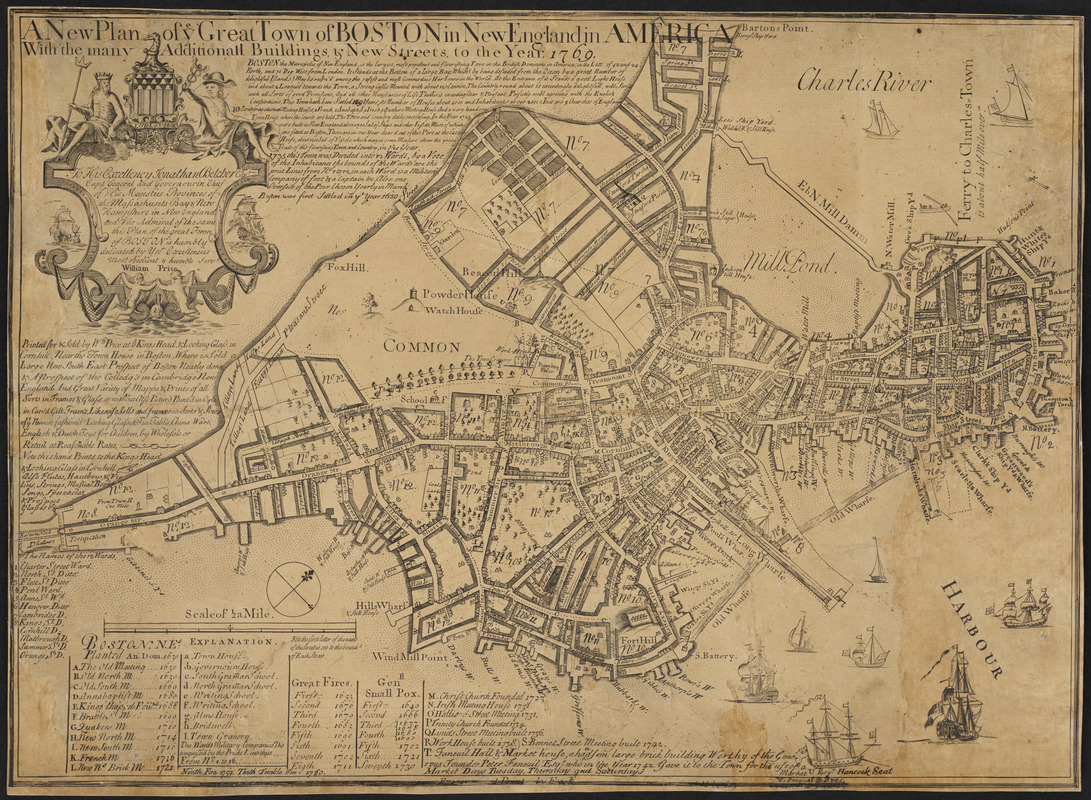

John Bonner (ca. 1643-1726) and William Price (fl. 1725-1769)

A New Plan of ye Great Town of Boston in New England in America, with the Many Additionall Buildings, & New Streets, to the Year 1769

Boston, 1769. Engraving, 17.5 x 24.5 inches

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

John Bonner’s 1722 map of Boston–the first published map of the city–provides a valuable record of pre-Revolutionary Boston. After Bonner’s death, his partner William Price continued to update and reprint it. Price printed this version in 1769 after the British troops occupied Boston. At that time, Boston was confined to a small peninsula connected to the mainland by one road along a narrow neck, very different from today’s landscape. Boston was a thickly settled town, with numerous wharves, attesting to the city’s status as a significant colonial port.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

Jean de Beaurain (fl. 1696 – ca. 1772)

Carte du port et havre de Boston avec les côtes adjacentes, dans laquelle on a tracée les camps et les retranchemens occupés, tant par les Anglois que par les Américains

Paris, 1776. Engraving, hand colored, 22.5 x 28 inches

Courtesy of Mapping Boston Foundation

This beautiful, meticulously-drawn French map of Boston’s harbor and environs uses the Liberty Tree and liberty pole icons to champion the Americans’ cause. In the decorative title cartouche, a Native American watches a Tory and Patriot struggle to gain possession of a liberty pole and a flag bearing the Liberty Tree image.

Based on hydrographic and military surveys by British engineers, this topographic map highlights Boston’s distinctive geography. The harbor is filled with islands and dangerous sandbars, while the surrounding countryside is dotted with hills. For Frenchmen interested in recent political events, the map also locates the positions of British and American troops during the British siege of Boston.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

Joseph F.W. Des Barres (1722-1824)

“A View of Boston Taken on the Road to Dorchester,” from The Atlantic Neptune

London, 1776. Engraving, 18 x 25.5 inches

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

This 1776 landscape scene, published in the maritime atlas The Atlantic Neptune, depicts Boston as it appeared to a person approaching the town from the south. Shepherds tend their flocks in the foreground, while the Shawmut Peninsula rises from the marshy flats in the background. Numerous church spires and the “beacon” on Beacon Hill are clearly visible on Boston’s skyline. Despite being an important trading port and one of the most populous cities in America, colonial Boston was small compared to a metropolis like London. Boston appears as a little coastal town surrounded by a vast wilderness.

1.1 Unrest Brews in Boston

In response to the passage of the 1765 Stamp Act, colonists asserted that Parliament could not tax the colonies. Virginia statesmen passed resolutions against the Act and Bostonians rioted. The Sons of Liberty gathered at a large elm tree near the Boston Common called the Liberty Tree, where they hung an effigy of the tax collector. The Liberty Tree and the liberty pole (a symbol dating from the Roman Empire) became emblems of the colonists’ cause and appeared on flags and map cartouches.

Parliament repealed the Stamp Act a year later, but Bostonians continued to resist new taxes. British soldiers occupied the city beginning in 1768 to enforce the laws. Tensions rose between the civilians and soldiers, setting the stage for the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770. Amidst growing unrest, a confrontation between soldiers and a group of rowdy boys attracted an angry crowd in front of the Town House (now the Old State House). The soldiers fired and killed five people, all workingmen. Colonists rallied around the Boston Massacre as an example of British brutality, and elevated the slain men to martyrs.

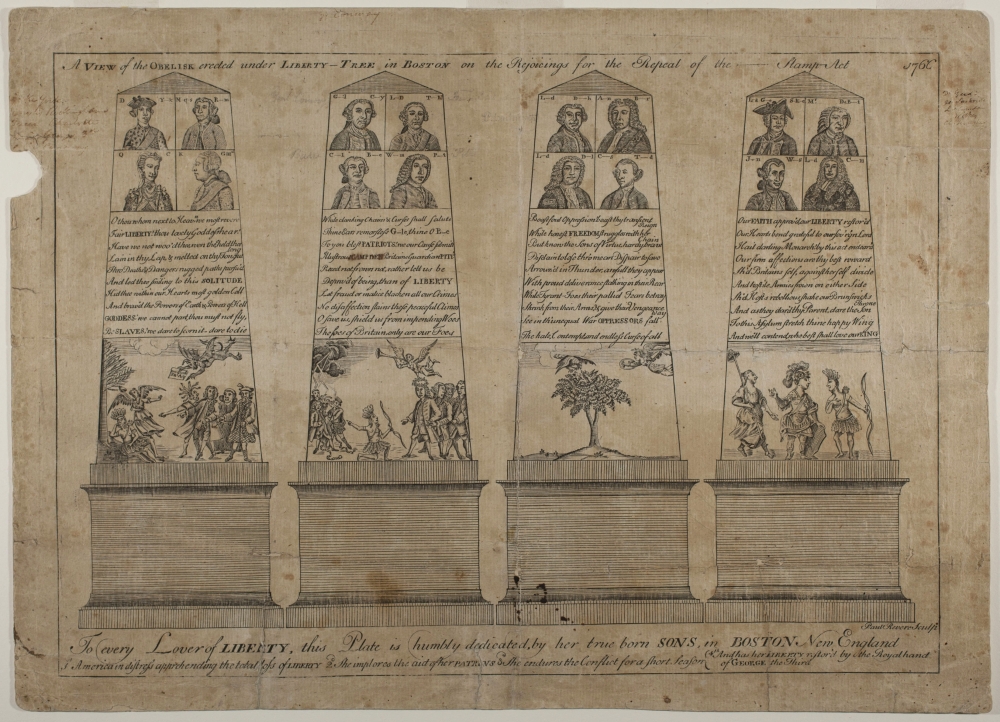

Paul Revere (1734-1818)

A View of the Obelisk

Boston, 1766. Line engraving, 9.5 x 13.5 inches

Courtesy of Boston Athenaeum

In 1766, Paul Revere engraved this print of an obelisk to commemorate the repeal of the Stamp Act. Destined for a spot beneath the Liberty Tree near the Boston Common, the obelisk burned before its installation. Revere, fortunately, recorded the details. The portraits depict the colonies’ most powerful supporters. Inscriptions at the base describe the scenes. On the left, is a distressed America, which is represented by a Native American woman wearing a feathered headdress and skirt. On the right, after enduring the Stamp Act conflict, Britannia restores liberty (represented by the woman with the pole and cap) to America.

After Benjamin Wilson (1721-1788)

The Repeal, or the Funeral Procession, of Miss Americ-Stamp

1766. Etching, 9 x 13.25 inches

Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Print Department

This cartoon represents the repeal of the Stamp Act in 1766 with a funeral procession. The small coffin symbolizes death of the voided law. Prominent ministers, lawyers, and statesmen who had supported the act process toward a vault. The Stamp Act had prompted colonists to boycott British imports. By featuring three ships, a row of warehouses, and crates of goods in the background, the artist suggests its repeal will improve trade. Londoner Benjamin Wilson designed the original cartoon, which sold roughly 16,000 copies. Many engravers copied the cartoon to profit from the image’s popularity.

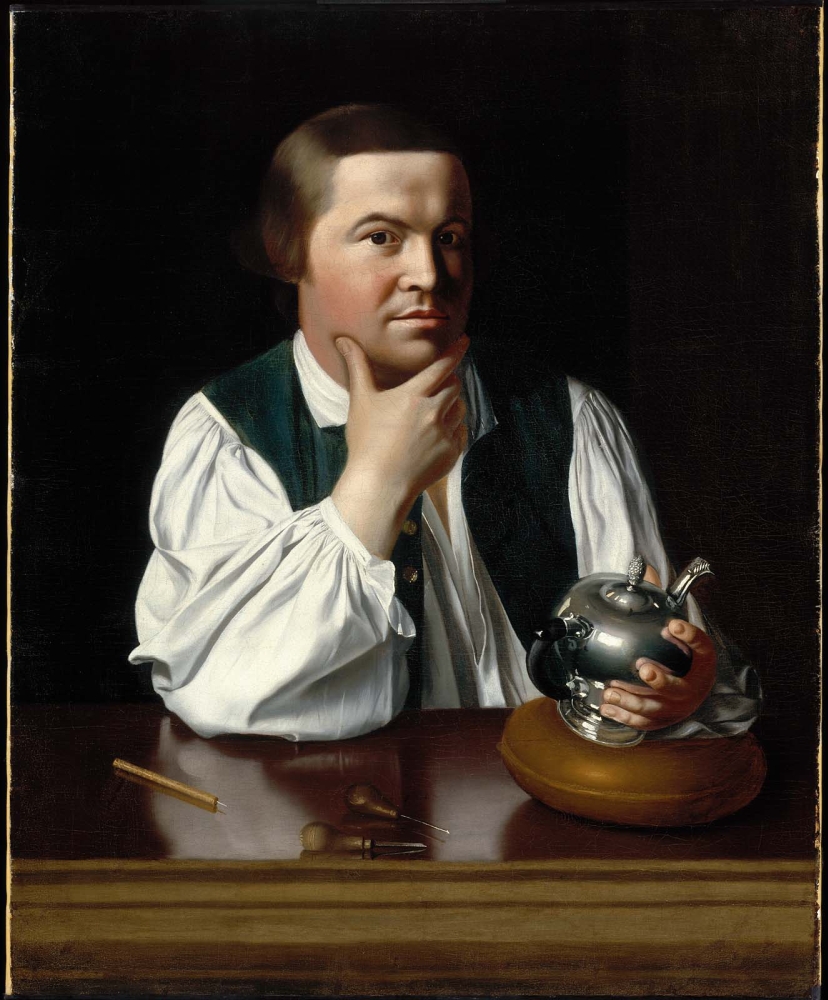

John Singleton Copley (1738–1815)

Paul Revere

Boston, 1768. Archival replica–fine art print, 35 x 28.5 inches

Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Gift of Joseph W. Revere, William B. Revere and Edward H.R. Revere, 30.781

Paul Revere was a Boston craftsman who also belonged to the Sons of Liberty. He is remembered for helping to alert the countryside that the British soldiers were marching to Lexington and Concord. During the revolutionary era, he created fine silver, including the Sons of Liberty Bowl that commemorated the patriotism of Massachusetts statesmen. Revere also engraved several items featured in this exhibition, including the Boston Massacre scene and the masthead for The Massachusetts Spy. Portrait artist John Singleton Copley portrayed Revere as a thoughtful man dedicated to his craft and the politics of rebellion (symbolized by the teapot).

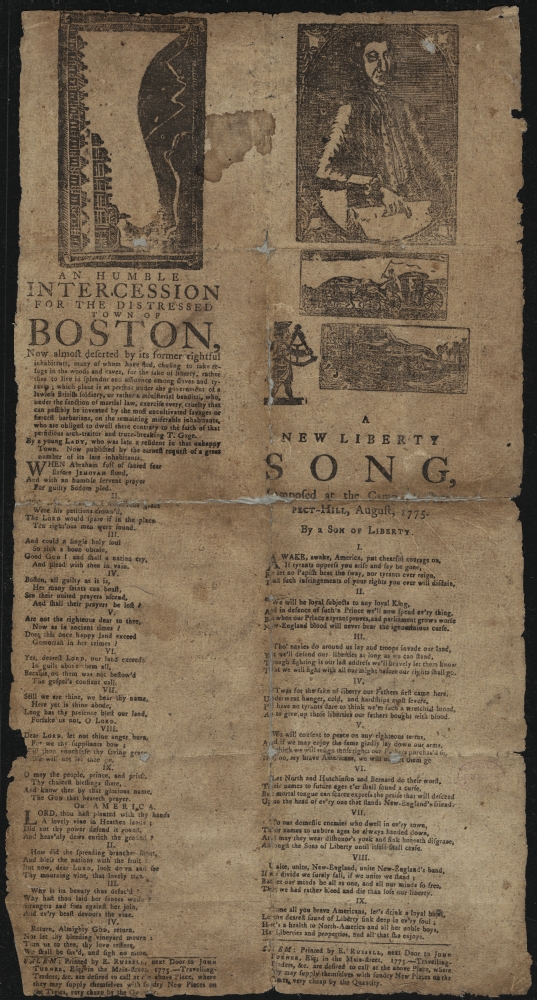

A New Liberty Song, 1775 by a Son of Liberty

[Boston], 1775. Printed broadside, 16.5 x 9 inches

Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Rare Books Department

This broadside features the lyrics for “A New Liberty Song,” written by a Son of Liberty. Variations of this song were popular during the revolution. The Sons of Liberty formed as colonists became discontent with British policies, especially the 1765 Stamp Act. New Yorkers started the first groups, and soon branches formed in other coastal cities. The Sons of Liberty mostly consisted of lawyers, merchants, and tradesmen. These men met in taverns to discuss politics and became leaders of the rebellion. The broadside also features a prayer by a “young Lady” for the miserable Bostonians living in the city during the siege.

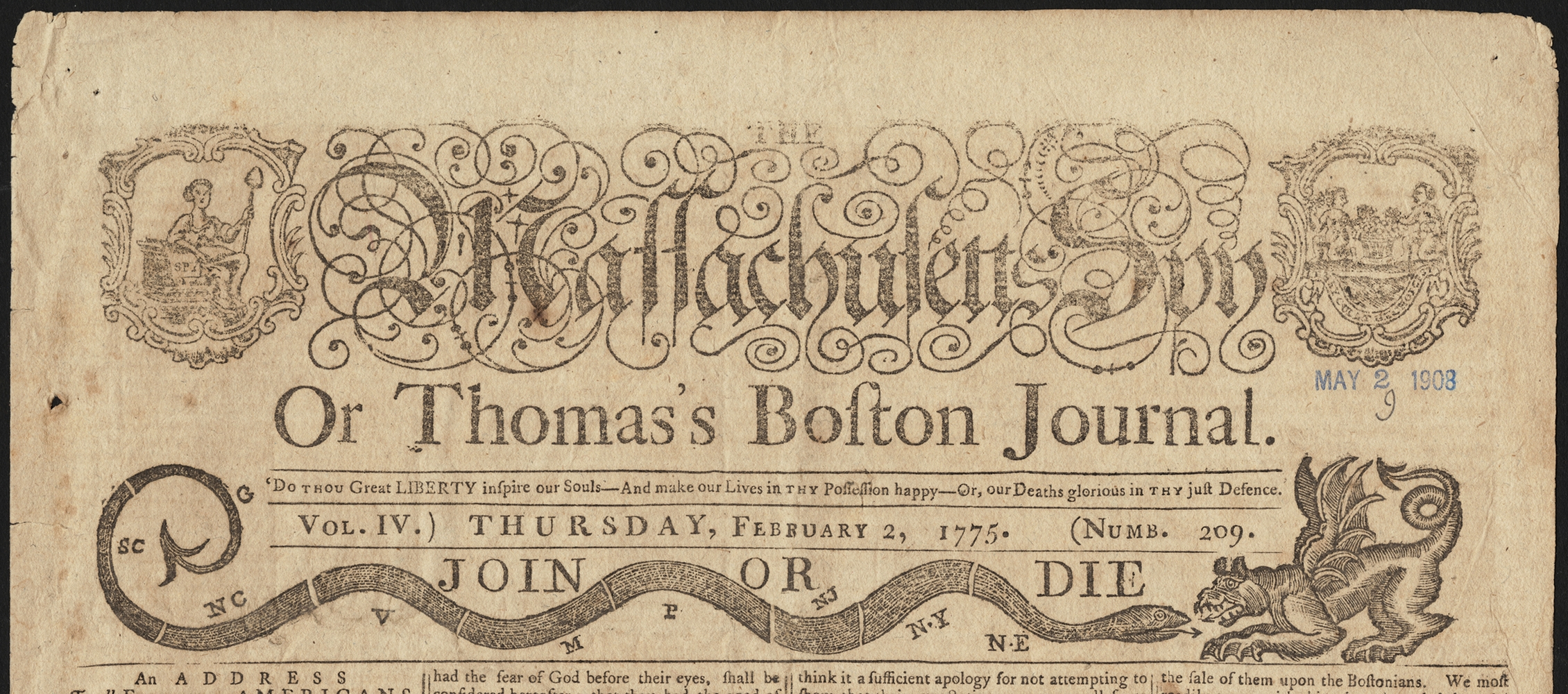

Paul Revere (1734-1818), after Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790)

“Join or Die” [Snake and dragon masthead], from The Massachusetts Spy

Boston, July 1, 1774. Newsprint with metal-cut engraving, 17.5 x 11 inches

Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Rare Books Department

Paul Revere engraved this masthead for The Massachusetts Spy less than a year before the battles at Lexington and Concord. He based his illustration on Benjamin Franklin’s “Join or Die” snake cartoon, published in The Pennsylvania Gazette on May 9, 1754, which served as a plea for the disconnected British colonies to unite against their enemy during the French and Indian War. Revere modified this map-like rendition of the eastern seaboard, by adding Georgia as the southernmost colony. Revere’s snake has two stingers, one at the mouth and another at the tail, to defend itself from the ferocious dragon representing Great Britain. Colonists used this as a symbol of unity throughout the war.

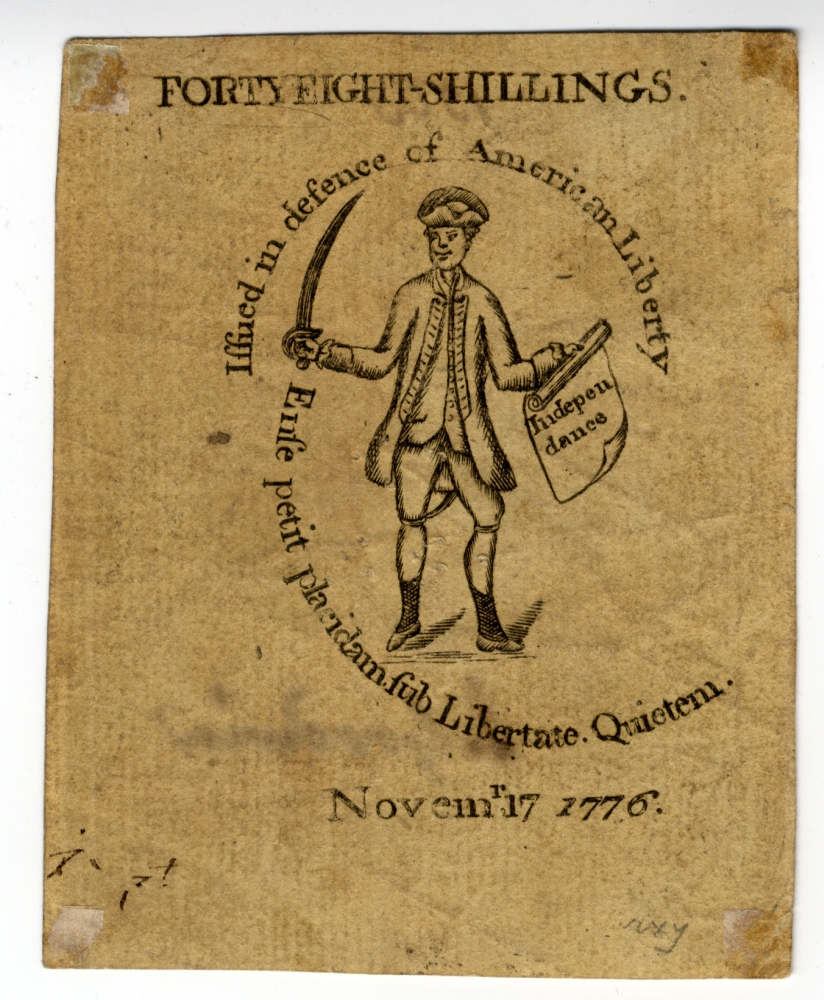

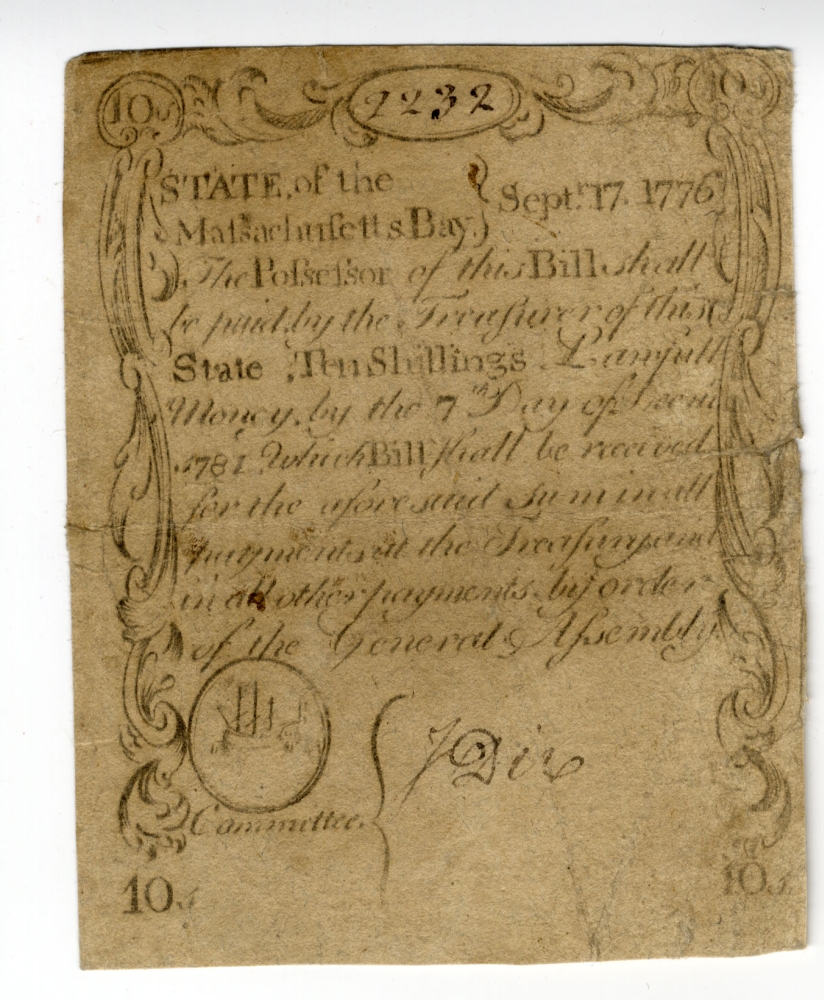

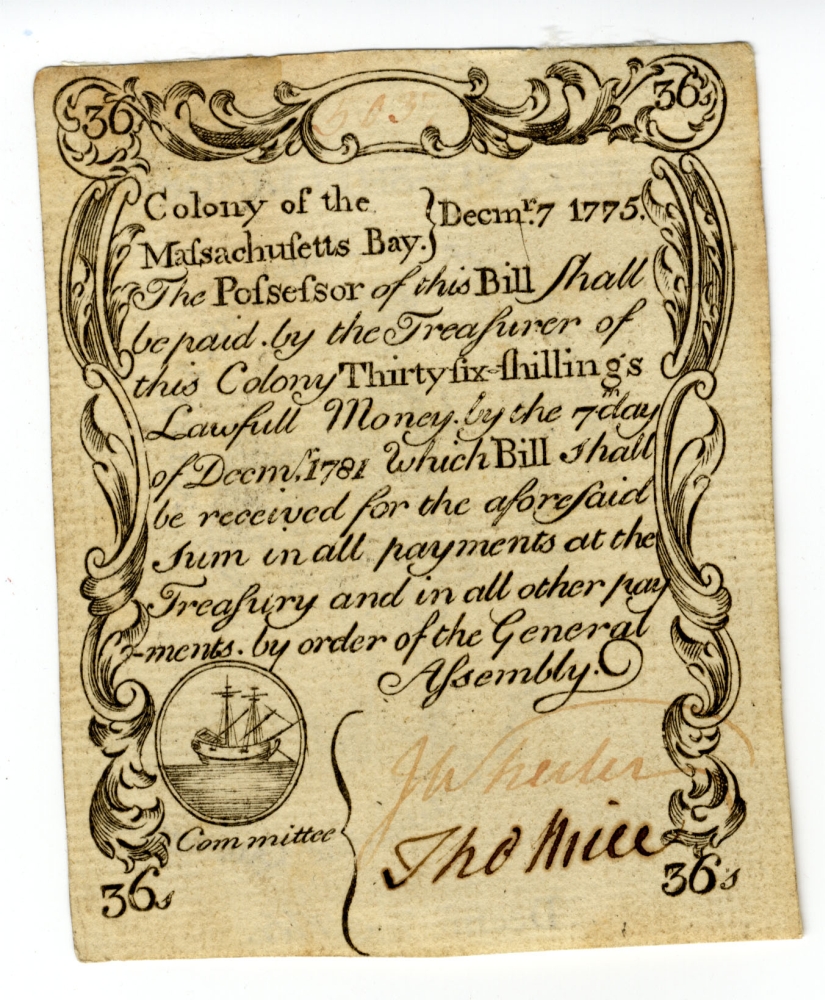

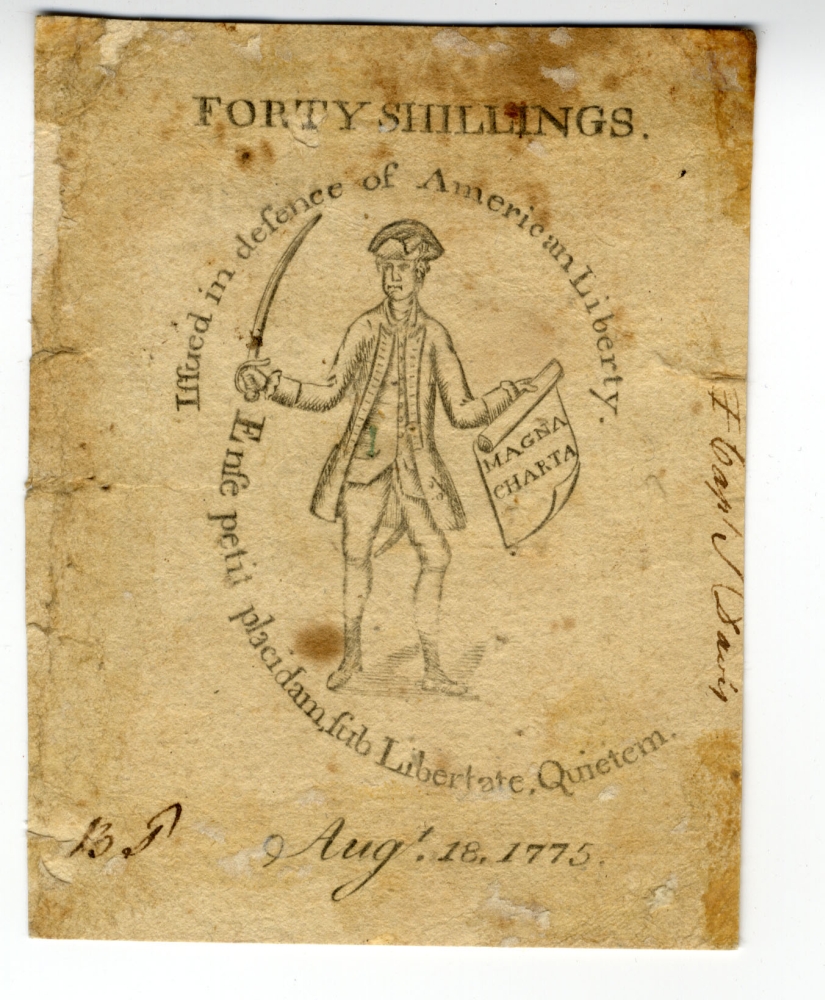

Paul Revere (1734-1818)

[Engraved Bills of Credit for Massachusetts Bay Colony, December 7, 1775 and November 17, 1776]

[Boston], 1775-1776. Printed currency, 3.75 x 3 inches

Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society

Colonial artisans like Paul Revere often worked on a diverse array of projects. Utilizing his skills as a silver artist, Revere engraved a view of Boston in 1770, showing the landing of the British troops. Five years later, he reused the same plate when he engraved designs for paper currency on the reverse side. The currency, known as “Sword in Hand” bills, shows an armed soldier holding a document, surrounded by the state motto of Massachusetts. “Magna Charta” appears on the 1775 bill, but by November 1776, it read “Independance.”

Paul Revere (1734-1818)

The Bloody Massacre Perpetrated in King-Street Boston on March 5th 1770 by a Party of ye 29th Reg[imen]t

Boston, 1770. Engraving, hand colored, 17 x 17 inches

Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Rare Books Department

In 1770 British soldiers fired into an angry crowd and killed five civilians, an event later called the Boston Massacre. Paul Revere, one of the Sons of Liberty, engraved this hand-colored print of the scene based on an engraving by Henry Pelham. By showing eight British soldiers firing in unison at helpless civilians, Revere aimed to inflame tensions between the colonists and soldiers. The red of the British coats matches the blood from the dying colonists. According to later testimony, Revere’s print was not entirely accurate. Still, it became a popular piece of visual propaganda against British rule.

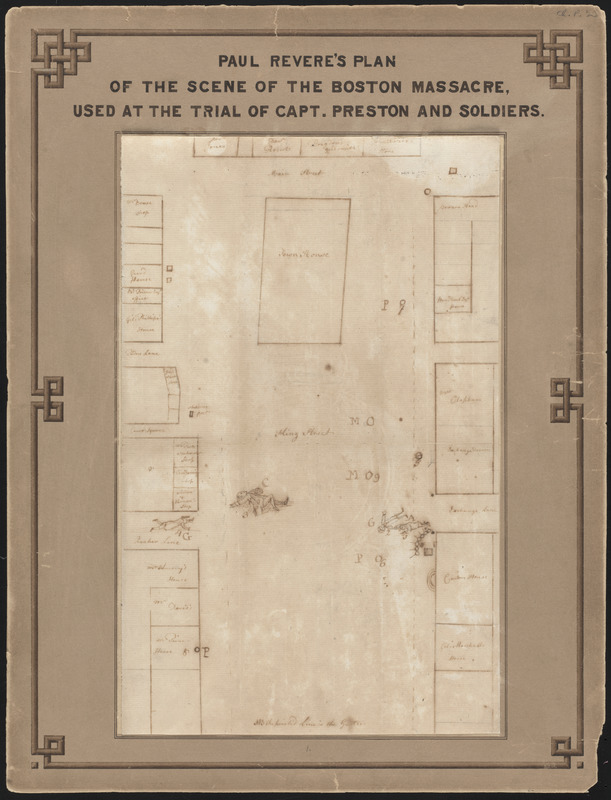

[Paul Revere] (1734-1818)

[Autograph Manuscript Drawing of the Boston Massacre]

[Boston], 1770. Manuscript, 13 x 8.25 inches

Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Rare Books Department

This diagram, attributed to Paul Revere, depicts the scene after British soldiers shot five civilians during the Boston Massacre. Unlike Revere’s colored engraving, this drawing provides a less embellished version of the scene. The plan shows four men lying dead in King Street (now State Street) in front of the Town House (now the Old State House). The artist might have completed the drawing before the death of the fifth victim or the victim may have been removed. The back of the document contains information consistent with docket procedures, indicating that the sketch may have been used in the subsequent trial of the British soldiers.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

1.2 Boston Tea Party

John Singleton Copley (1738-1815)

Mrs. James Smith (Elizabeth Murray)

Boston, 1769. Archival replica–fine art print, 50 x 40 inches

Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Gift of Joseph W.R. Rogers and Mary C. Rogers, 42.463

Born in Scotland in 1726, Elizabeth Murray settled in Boston in 1749. She had her own shop and sold a variety of British goods. She married three times and required two of her husbands to sign prenuptial agreements that guaranteed her legal independence. This was uncommon for married women at that time. Like others, Murray had divided loyalties when the rebellion began. She maintained associations with both sides throughout the conflict. This portrait by John Singleton Copley, Boston’s most prominent portrait artist of the period, depicts Murray in fine clothes, standing in front of a bucolic scene.

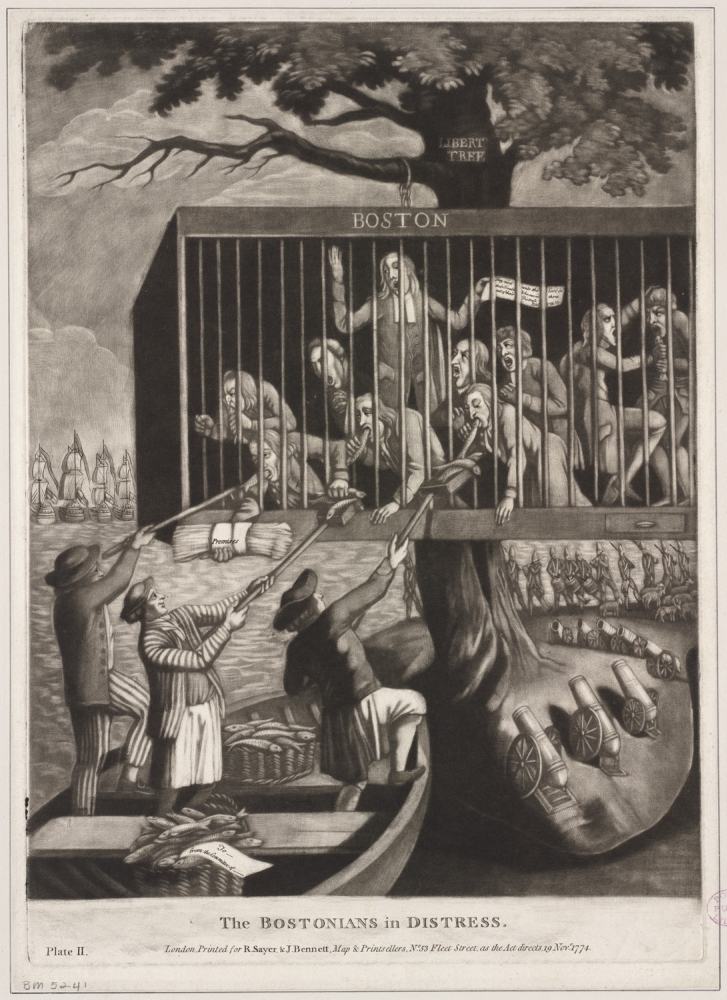

Philip Dawe (d. 1832)

The Bostonians in Distress

London, 1774. Mezzotint, 14.5 x 10.5 inches

Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Print Department

This print alludes to the closure of Boston’s port, the heart of the city’s economy. Protestors refused to pay for the tea after the tea party. The ships, soldiers, and cannons refer to their punishment: a British blockade. Cages like this one were used to punish slaves. By incorporating the cage and Liberty Tree, the artist implied that the new laws had taken away freedoms from the Bostonians. Despite the blockade, three men, representing other colonies, offer fish to sustain the caged Bostonians. The scene may offer a sympathetic view of Boston’s plight or it may have been intended to gratify British sensibilities.

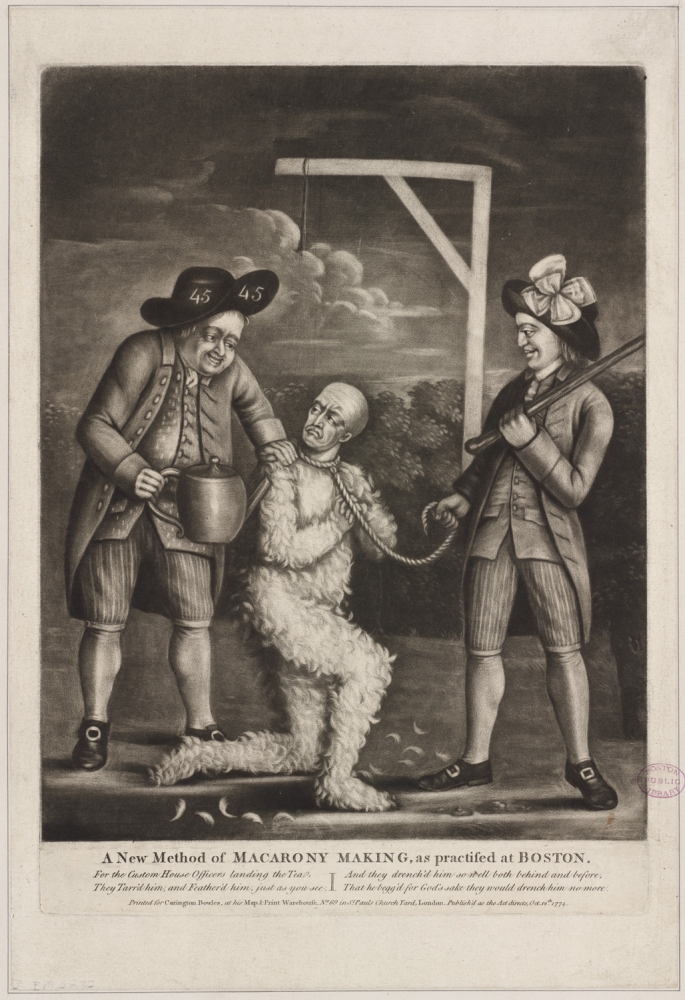

[Philip Dawe] (d. 1832)

A New Method of Macarony Making, as Practised at Boston

London, 1774. Mezzotint, 9.25 x 12.75 inches

Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Print Department

This print depicts two Sons of Liberty tarring and feathering a British customs official in Boston in January 1774. The tax collector kneels for the Sons of Liberty, one of whom is about to force him to drink tea. The “Macarony” in the title refers to a popular, elaborate style of wig. By representing the officer without his wig in a state of undress, the artist aimed to embarrass the official. The cartoon’s origin in London demonstrates that people on both sides of the Atlantic were eager to discuss the backlash resulting from the taxes levied on the colonies.

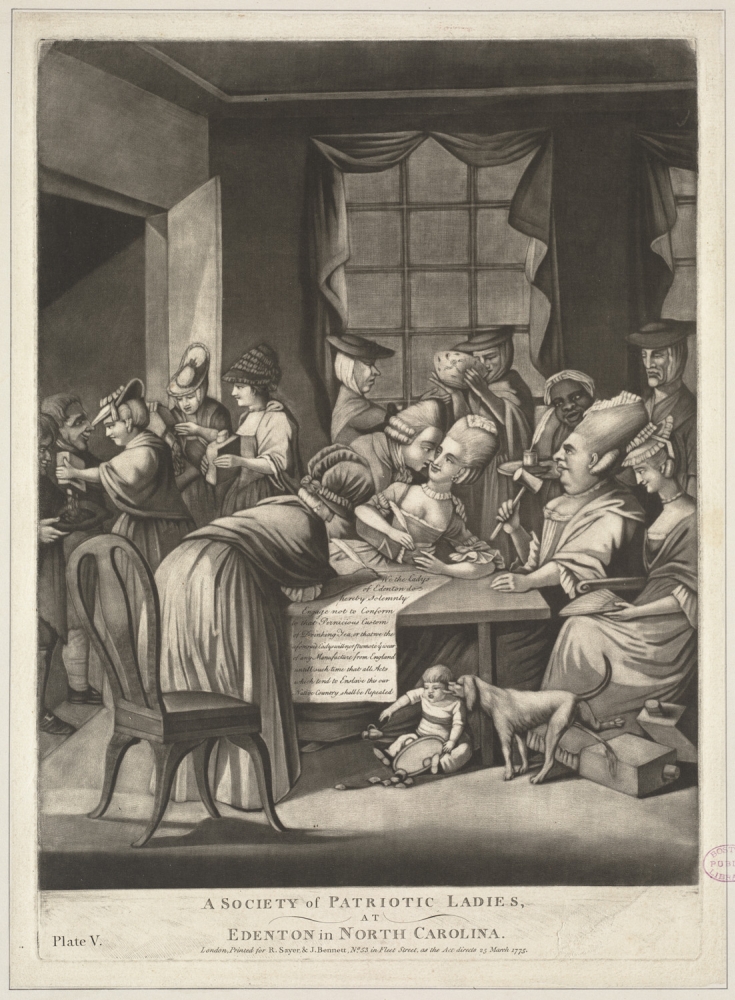

Philip Dawe (d. 1832)

A Society of Patriotic Ladies, at Edenton in North Carolina

London, 1775. Mezzotint, 14.75 x 10.75 inches

Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Print Department

In 1775 London artist Philip Dawe engraved this print in response to the shocking news that women, who were not allowed to vote or run for office, joined the resistance to the tea tax. Dawe lampooned the 51 women of Edenton, North Carolina who signed a resolution to stop drinking tea, a popular social ritual. This print suggests the rebellion caused social as well as political upheaval. Political women dump the contents of their tea canisters and sign the resolution as they neglect the child under the table. A black female slave looks eagerly at the petition for American liberties.

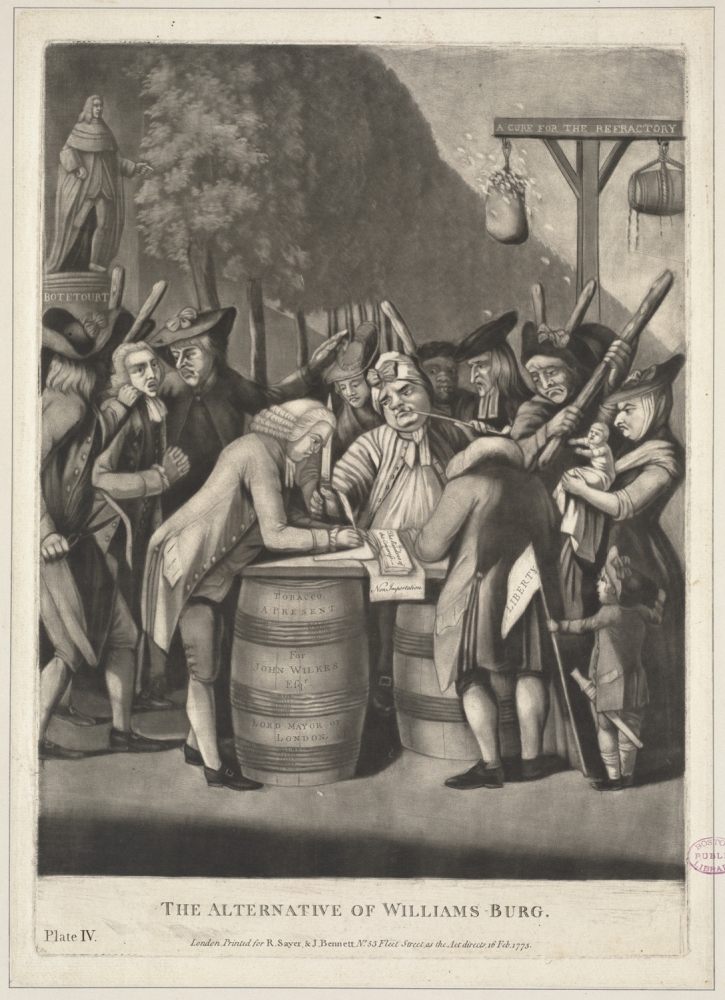

Philip Dawe (d. 1832)

The Alternative of Williams-burg

London, 1775. Mezzotint, 15 x 10.5 inches

Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Print Department

London artist Philip Dawe depicted a group of Virginians signing a resolution to withhold tobacco exports until the British government repealed all taxes on imported goods. Since tobacco was profitable, not all Virginians supported the measure. A crowd of angry men, women, and children force hesitant men to sign the resolution. The alternative is clear: a man in the center wields a knife, others hold clubs, and containers of tar and feathers hang from a post in the background. The print suggests that unruly crowds, rather than upstanding gentlemen, had taken charge of the American rebellion.

[Teapot, Owned by Crispus Attucks]

1750-1770. Pewter, tin, wood, 5 x 7.5 x 4.5 inches

Courtesy of Historic New England

Gift of Miss S.E. Kimball through the Bostonian Society, 1918.1655

[Teapot with Lid]

China, 1750-1775. Porcelain, enamel, paint, 5 inches in height

Courtesy of Historic New England

Gift of Miss Margaret Jewell, 1958.516

Drinking tea was an important ritual among American colonists, especially women. However, it was a common practice regardless of race or class, as evidenced by these two tea pots.

The first belonged to Crispus Attucks, who was one of five colonists shot by British soldiers during the 1770 Boston Massacre. Attucks was likely an escaped slave, and he may have had Native American, African, and European ancestry. His teapot highlights the lives of ordinary people who participated in the rebellion.

Unlike Crispus Attucks’s plain pewter teapot, the second is made of fine Chinese porcelain and features a Chinese man, woman, and child within a medallion. Tea and teapots became politicized and came to represent unjust British rule and European frivolities.

2 Britain's North American Empire

By the mid-eighteenth century, thirteen British colonies stretched more than 1,200 miles along the Atlantic Coast from Georgia to Maine. Since the founding of Virginia in 1607, these colonies had become integral to the expanding British Empire. This section of the exhibition focuses on the aftermath of the French and Indian War (1754-1763) when Britain added land from the French, Native Americans, and Spanish to its North American territories.

The British government attempted to manage and consolidate these vast holdings. King George III established the Proclamation Line of 1763 along the Appalachians to prohibit colonial settlement beyond the mountains. Parliament levied new taxes to pay for the war and to defend the colonies. These efforts gradually strained relations between the colonists and London.

2.1 London and the Atlantic World

Eighteenth-century London was the largest city in Europe and the metropolis for a global empire based on commerce. These maps, which range from large-scale floor plans of the Royal Exchange to small-scale maps of Europe and the North Atlantic Ocean, offer a sense of London’s role as the commercial hub of a colonial empire competing with other European powers for political and economic dominance in the Atlantic world. Powerful though it was, London’s economy was subject to the changing political climate in the colonies. London workers lost jobs and merchants lost money when colonists boycotted British imports. These connections emphasize the strong ties between London and her North American colonies.

Georg Balthasar Probst (1732-1801)

[View of] London

Augsburg, ca. 1770-1780. Engraving, hand colored, 25.5 x 54 inches

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

Twenty times the size of colonial Boston, London led the world in commercial trade, manufacturing, and finance. The River Thames flows through the city center. Ships brought commercial goods from around the world, including tobacco, rice, indigo and cotton from America. The city inspired wonder, as conveyed in this engraving published by a printer from Augsburg, Germany. It was translated into English and Latin for an international audience. The focal point is St. Paul’s Cathedral, designed by Christopher Wren and built in 1711. The legend identifies 70 prominent buildings and landmarks, including the Royal Exchange, where colonial merchants regularly met to conduct business.

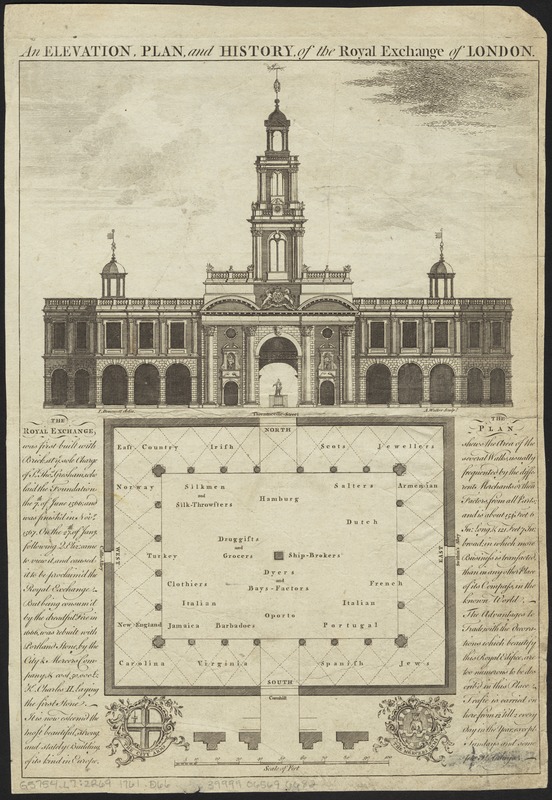

John Donowell (fl. 1753-1786) and Anthony Walker (1726-1765)

An Elevation, Plan and History of the Royal Exchange of London

London, 1761-1786. Engraving, 13.5 x 9.25 inches

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

In contrast to Probst’s map of London, this print provides a large-scale depiction of the city’s Royal Exchange, the hub of commerce for the British Empire. In this building, people purchased and sold goods and spread news from around the world through conversations, books, and newspapers. The interior floor plan designates spaces for traders from the British colonies in America, Jamaica, and Barbados as well as European nations. Chesapeake tobacco planters and New England merchants depended on news and prices from the Exchange. The elevation documents the building’s Neoclassical façade, constructed after the first Exchange burned in the Great Fire of 1666.

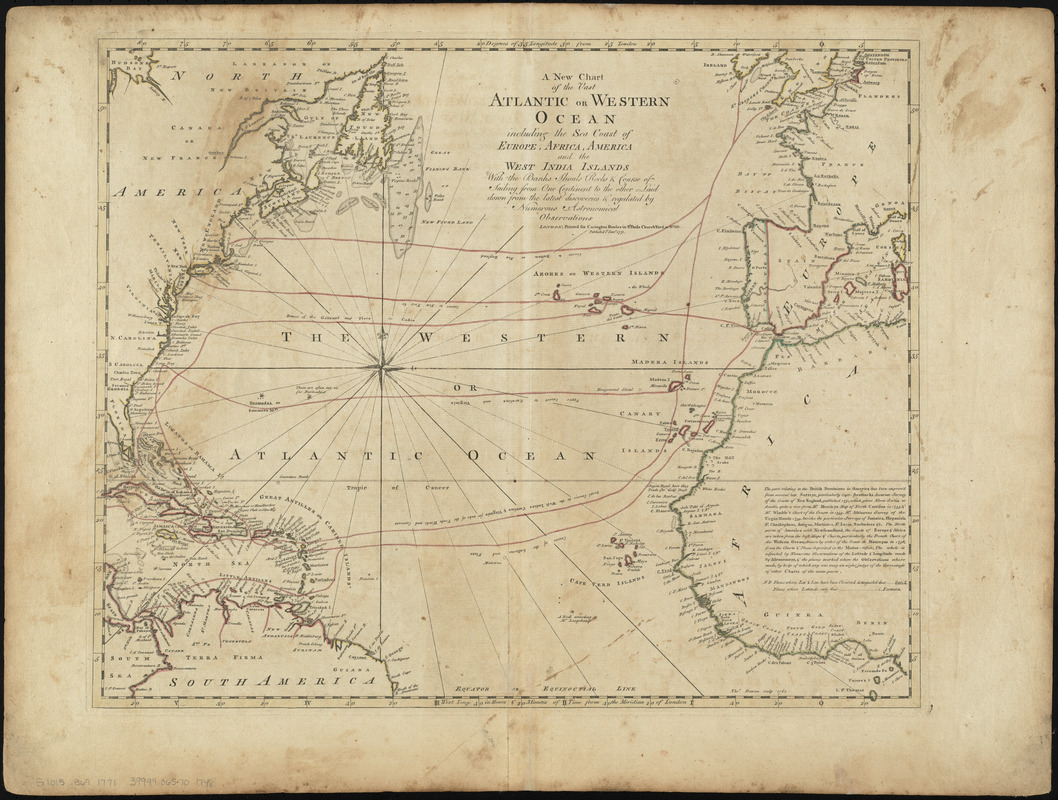

Carrington Bowles (1724-1793)

“A New Chart of the Vast Atlantic or Western Ocean including the Sea Coast of Europe, Africa, America and the West India Islands,” from A General Atlas of Thirty-Six New and Correct Maps

London, 1771. Engraving, hand colored, 21 x 27.5 inches

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

Most ships used well-established routes to cross the North Atlantic during the colonial period. However, few contemporary maps depict specific voyages. This 1771 chart delineates several general routes, such as the “usual course to the West Indies, Carolinas & Virginia for sake of the Trade Winds and Currents.” Contrast these with the ones represented on the map of colonial shipping routes compiled in 2013, which was based on specific voyages documented in ships’ logbooks. For example, the 1771 map shows ships landing in Boston, New York, and Charleston, while the modern one notes that ships arrived all along the coast of the North American colonies.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

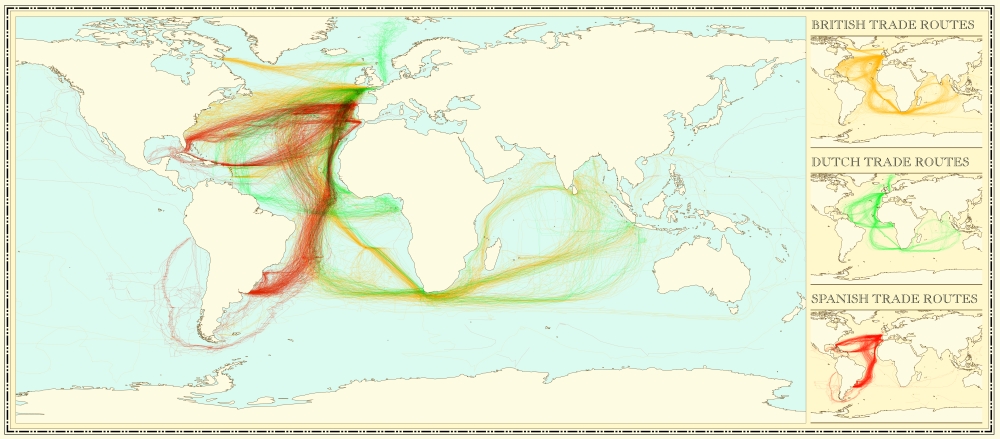

Mapping by James Cheshire and design by Valentina D’Efilippo

[Major Shipping Routes in the Colonial Era]

2015, Reproduction from digital file, 13 x 30 inches

Courtesy of the Authors

This modern map portrays trade routes used by British (yellow), Dutch (green), and Spanish (red) ships between 1750 and 1800. All three focused on Caribbean destinations. The British also traded with eastern North America, while the Dutch had commercial contacts with northern South America. Spanish trade routes included southern North America and extended to South America. These trade patterns were reconstructed using a dataset compiled by the Climatological Database for the World’s Oceans based on sailor’s logbooks that recorded the ship’s location and weather conditions. Applying new technology to historical documents, as done in this map, can yield new insights into the past.

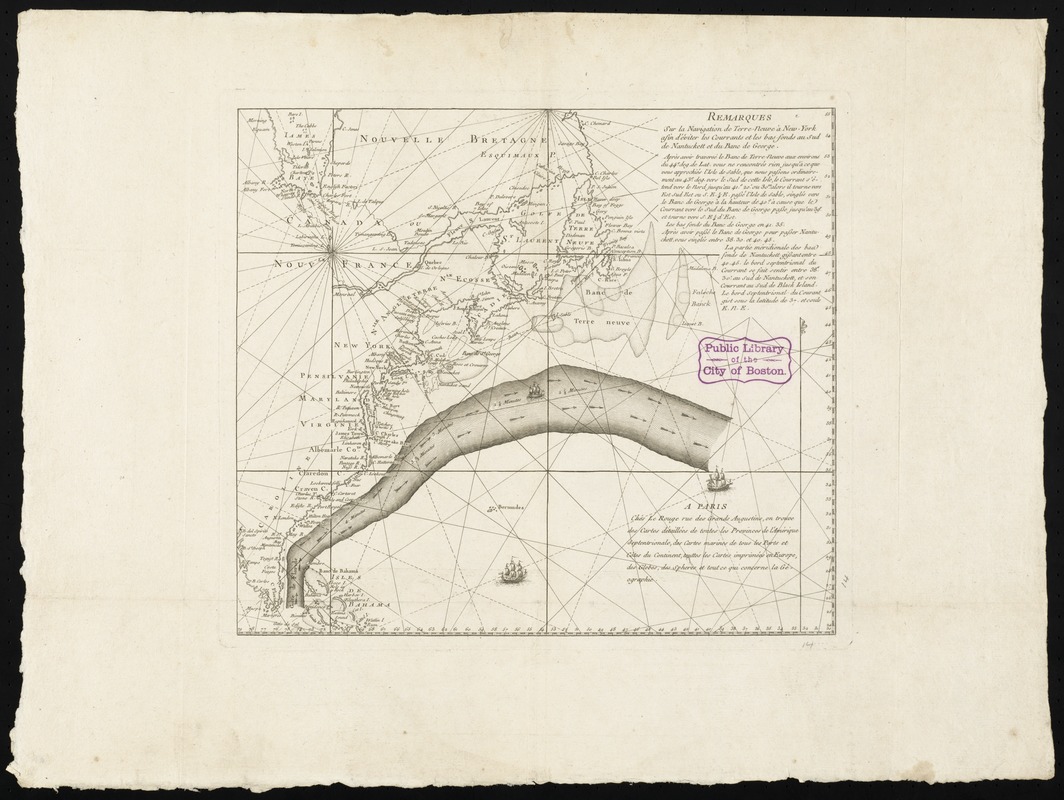

Georges-Louis Le Rouge (ca. 1712-ca. 1790)

Remarques sur la Navigation de Terre-Neuve à New-York afin d’Eviter les Courrants et les Bas-fonds au Sud de Nantuckett et du Banc de George

Paris, 1785. Engraving, 19 x 25 inches

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

Conservation funded by Lavinia Lee Witt Touchton in memory of her father Currie B. Witt

One of the preferred routes that captains and navigators sailing from America to England learned to use was the Gulf Stream, a strong, warm current that flows north along the Atlantic coast and then east toward Europe. Initially charted by Benjamin Franklin in 1768, this discovery helped ships minimize travel time across the ocean, speeding up the transatlantic voyage for travelers, merchants, and goods. Franklin purchased this 1785 chart, a French adaptation of his original findings, when he served in Paris as a diplomat for the United States during the early years of the republic.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

2.2 The Colonies

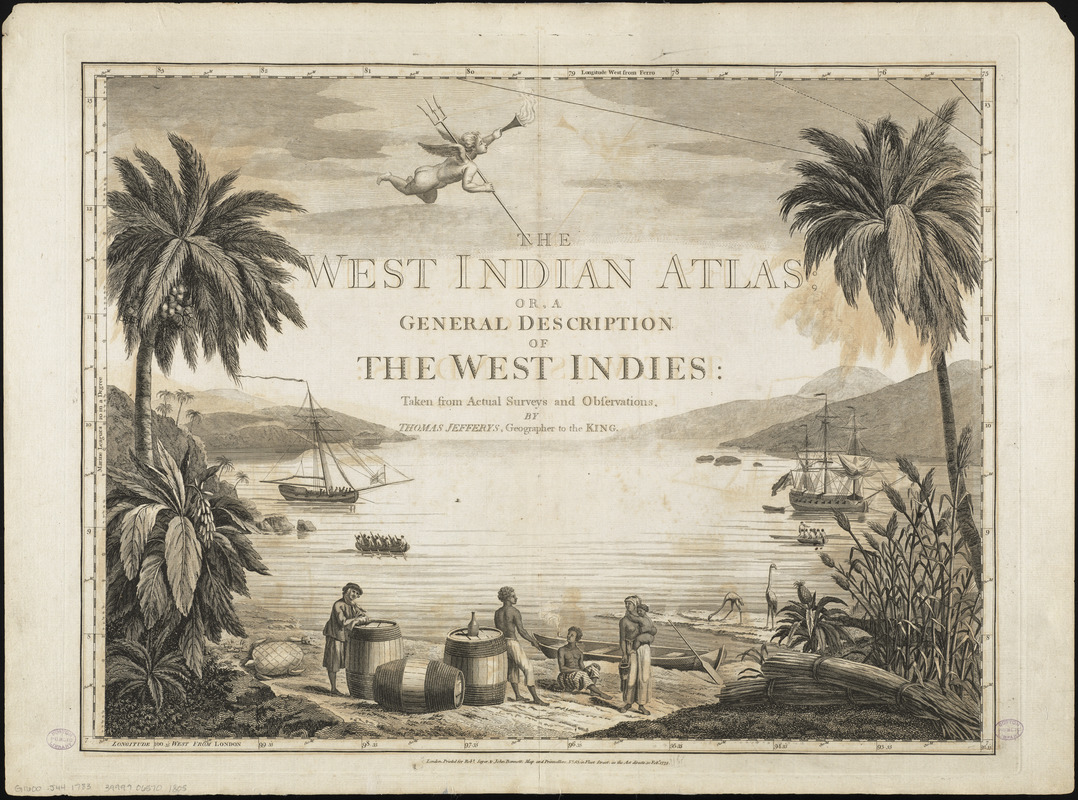

Thomas Jefferys (ca. 1710-1771)

Frontispiece from The West India Atlas: or a Compendious Description of the West Indies

London, 1783. Engraving, 18.75 x 24.5 inches

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

Thomas Jefferys, Geographer to the King, compiled an atlas devoted exclusively to the Caribbean region because of its importance within Britain’s commercial empire. The atlas’s frontispiece, like map cartouches of the period, aims to evoke the economic and cultural landscape of the region. This iconic scene shows the African slaves who worked the Caribbean sugar plantations, which had very high mortality rates. Bundles of sugar cane lie on the right. The barrels shown most likely contain molasses, a byproduct of sugar production and a chief export along with sugar. The large ships in the background could have transported these commodities to other North American colonies or Europe.

Georges-Louis Le Rouge (ca. 1712-ca. 1790) after Robert Baker (fl. mid-18th century)

Antigue: Levée par Robert Baker, Arpenteur General de l’Isle

Paris, 1779. Engraving, hand colored, 18 x 23.5 inches

Courtesy of Richard H. Brown

Barbados and Jamaica were Britain’s major sugar islands, but smaller islands like Antigua also produced sugar for British markets. Based on a 1746 map by Robert Baker, the island’s surveyor general, this version was republished for a French audience. The map reflects the intense competition between the French and British in the West Indies sugar trade. The map depicts roads (colored yellow) crisscrossing the island, while sugar mills powered by wind and cattle (colored red) dot the landscape. On the northern coast of the island, the area labeled “Royal’s Bay” indicates where the Royall family of Medford, Massachusetts owned a sugar plantation.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

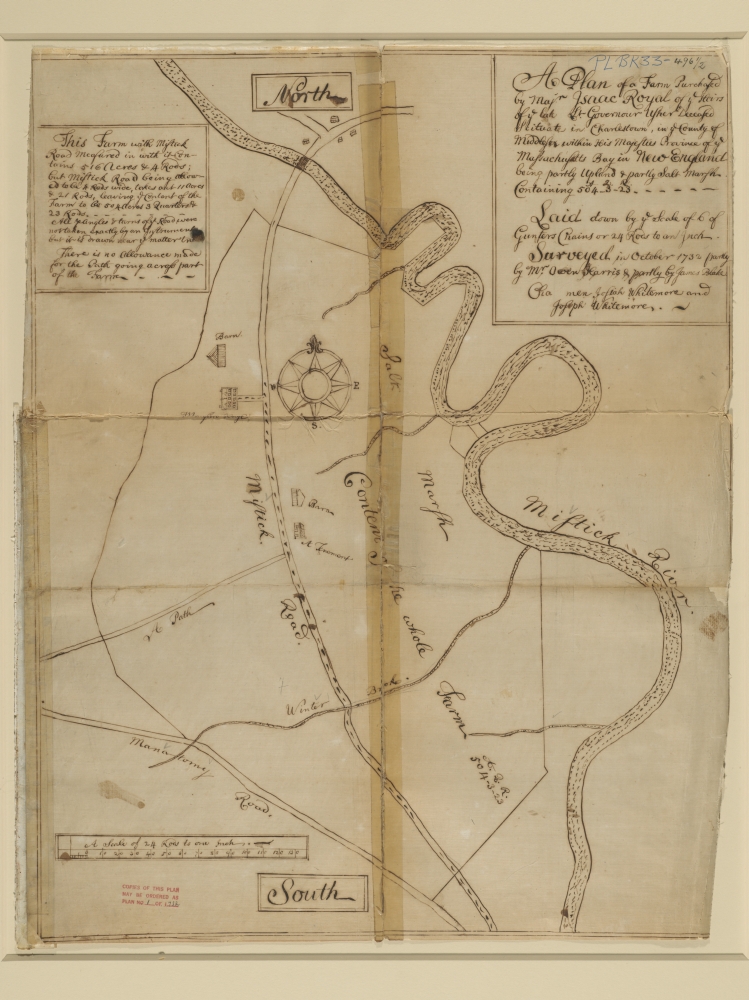

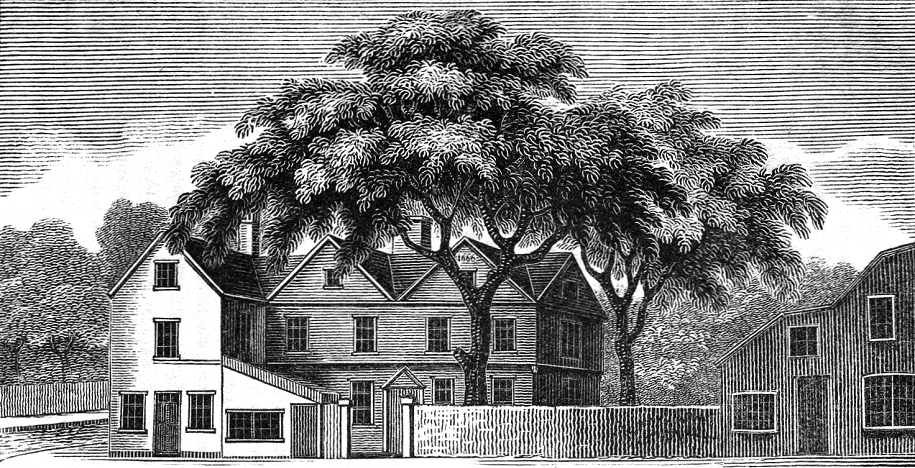

Owen Harris (ca. 1675-1761) and James Blake (1688-1751)

A Plan of a Farm Purchased by Majr. Isaac Royal…

1732. Reproduction of manuscript survey plat, 31 x 26 inches

Courtesy of Royall House and Slave Quarters

Isaac Royall, Sr., an Antigua sugar plantation owner, moved to Medford, Massachusetts after purchasing a 516 acre property on the Mystic River. This 1732 survey plat depicts the land, which included the farmhouse originally owned by Massachusetts Governor John Winthrop. Royall expanded the house into a three-story mansion and constructed separate quarters for the twenty-seven enslaved Africans the family brought with them.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

Robert Feke (1707- 1752)

Isaac Royall and His Family

1741. Reproduction of oil on canvas, 56 x 78 inches

Courtesy of Historical & Special Collections, Harvard Law School

Isaac Royall’s son (Junior), who is portrayed in this 1741 family portrait, inherited the estate in 1739. The family was one of the wealthiest in Massachusetts and had strong ties to Loyalists during the revolution. Guests can still visit the estate, which has the only surviving slave quarters in New England. The painting of the Royall family reproduced here is owned by the Harvard Law School, which was founded in 1817 using proceeds from the Royall estate.

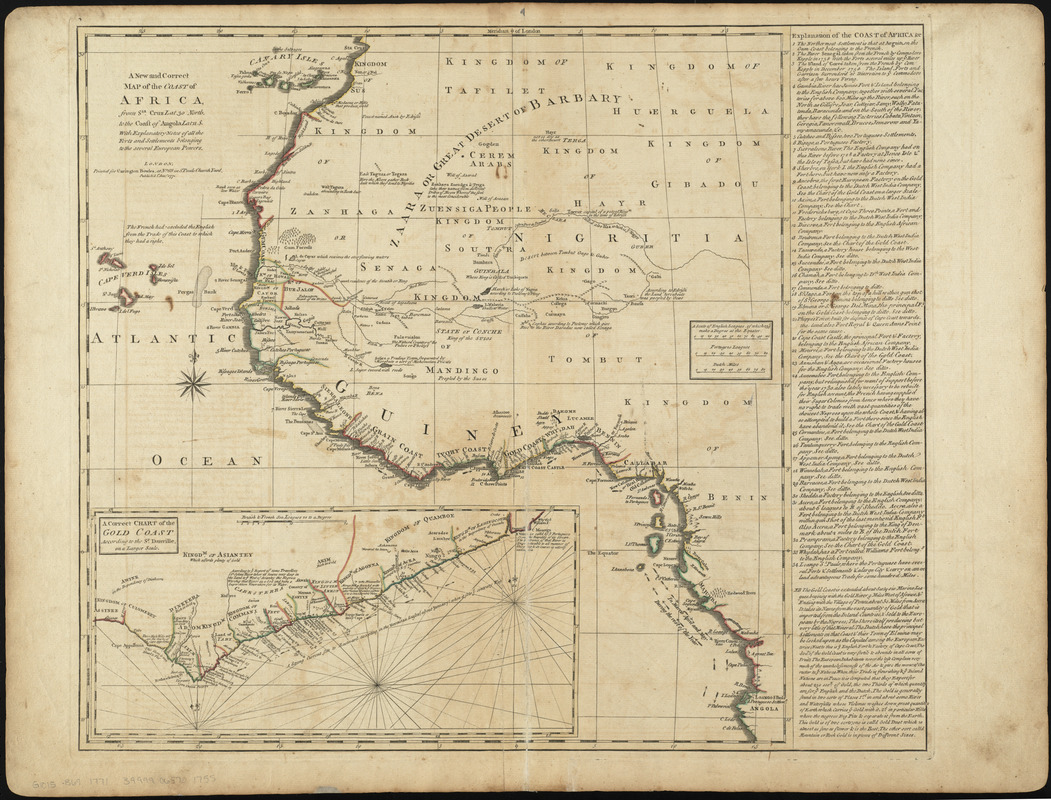

Carrington Bowles (1724-1793)

“A New and Correct Map of the Coast of Africa… with Explanatory Notes of all the Forts and Settlements Belonging to the Several European Powers,” from A General Atlas of Thirty-Six New and Correct Maps

London, 1771. Engraving, hand colored, 21 x 27.5 inches

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

Many enslaved Africans in the West Indies and North America came from the West Coast of Africa. Scholars believe that poet Phillis Wheatley, for example, lived in this region before she endured the Middle Passage and came to Boston as a young girl.

This map illustrates the intersection of native African and European cultures in western Africa during the mid-18th century. Besides designating which native kingdoms ruled the coastal regions, it also locates European settlements, forts, and trading sites along the coast. The inset map and marginal legend identify individual ports by nationality. These European footholds were used in the slave trade and to export natural resources like gold.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

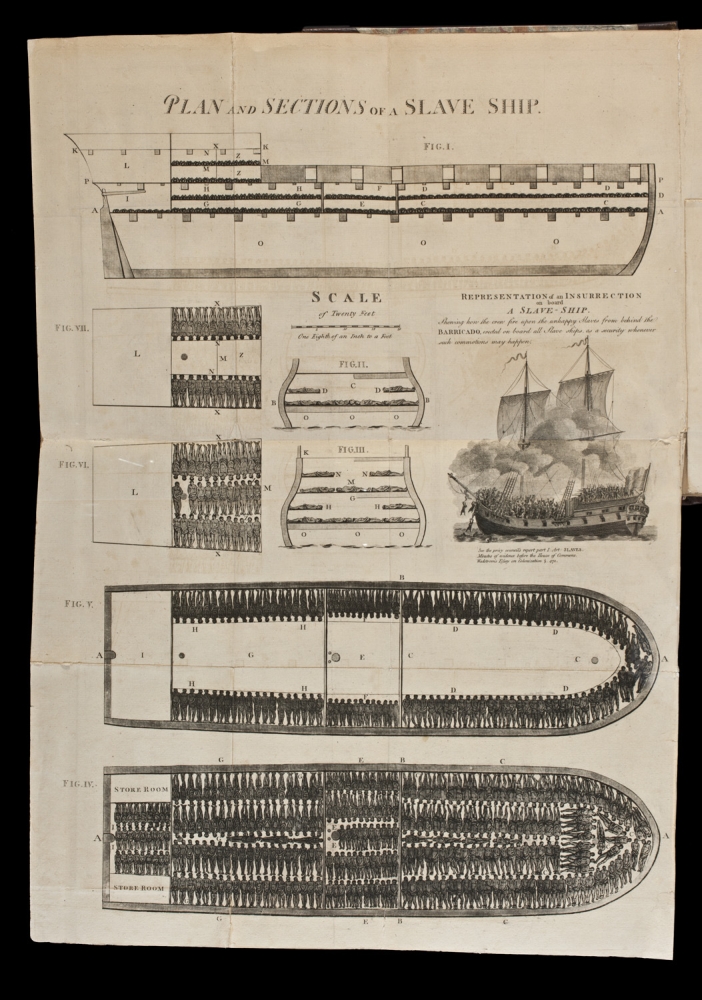

“Plan and Section of a Slave Ship,” in Carl B. Wadstrom, An Essay on Colonization, Particularly Applied to the Western Coast of Africa

London, 1794. Engraving, 21 x 14.5 inches

Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Rare Books Department

The production of many colonial exports relied on the labor of enslaved Africans. Slave ships, such as the one illustrated here, carried men, women, and children from Africa’s West Coast across the Atlantic to support the growing colonial economy. Antislavery reformers distributed plans of slave ships to demonstrate the cruelty of this practice. The ship’s floor plans provided a map of the lower decks filled with rows of human cargo. The British Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade first published a version of the slave ship Brookes in 1788, and the image became an icon of the antislavery movement.

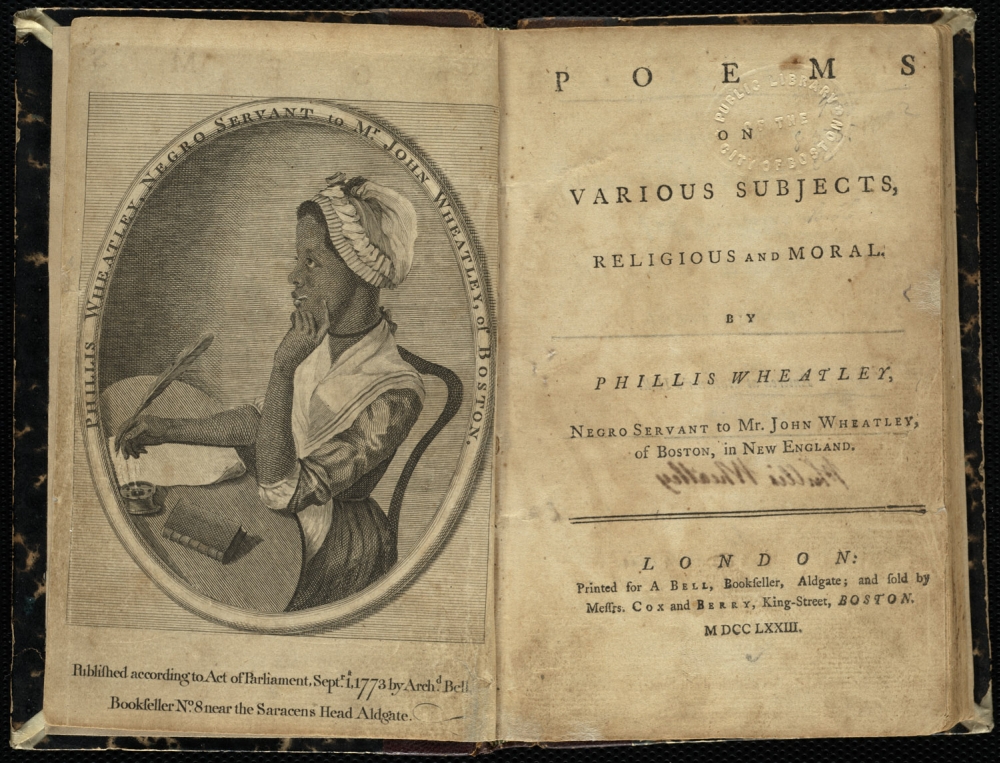

“Phillis Wheatley, Negro Servant to Mrs. John Wheatley, of Boston,” in Phillis Wheatley, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral

London, 1773. Engraving, 6.75 x 9.25 inches

Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Rare Books Department

Phillis Wheatley was forced to come to Boston as a slave from Africa when she was around eight years old. She received an usually good education for a woman, especially a slave, and became a prominent poet. Her poems often addressed public figures like George Washington and were published in America and England. In this portrait from her book of poems, Wheatley sits at her desk with her quill thinking about her next lines. The portrait challenged racial hierarchies by representing her as an author instead of a slave. The Wheatleys emancipated her soon after the book’s publication. She died in 1784 without publishing another volume.

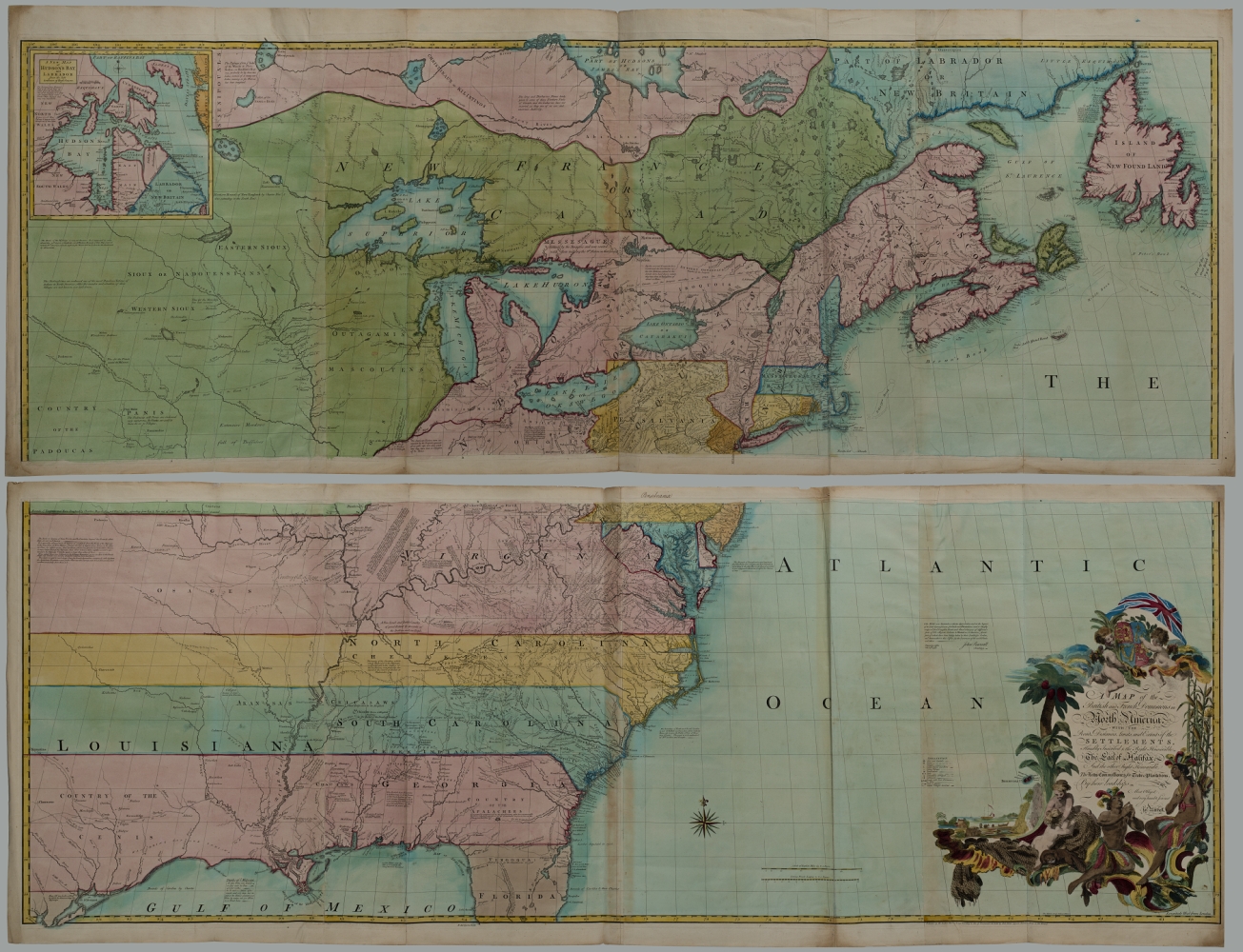

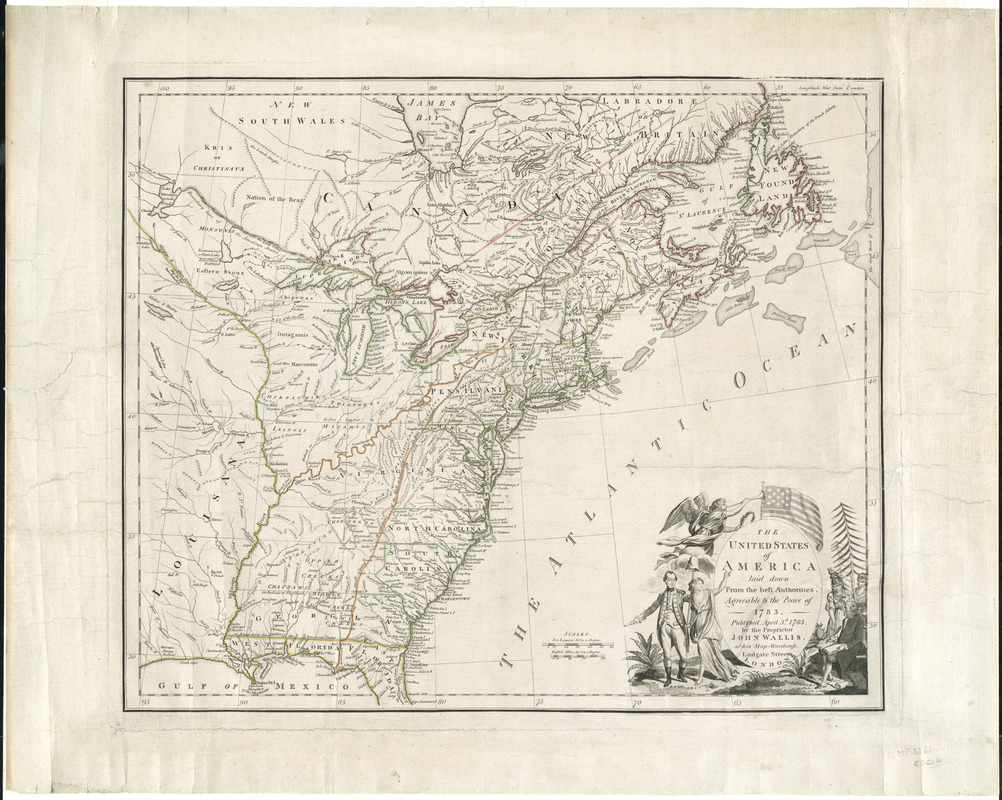

John Mitchell (1711-1768)

A Map of the British and French Dominions in North America with the Roads, Distances, Limits, and Extent of the Settlements, Humbly Inscribed to the Right Honourable the Earl of Halifax and the Other Right Honourable, the Lords Commissioners for Trade and Plantations

London, 1755. Engraving, hand colored, 54 x 77 inches

Courtesy of Carolyn and Michael McNamara

John Mitchell, a botanist and physician from Virginia, and the Earl of Halifax, his patron in the creation of this map, set out to provide the British government and the public with a better understanding of the geography of North America. The result was the most comprehensive cartographic representation of the colonies of its day. Mitchell emphasized the British Empire’s claims at the expense of French settlements. The map helped to galvanize public sentiment in favor of defending British holdings during the French and Indian War (1754-1763). Following the Revolutionary War, treaty negotiators used Mitchell’s map to establish the boundaries of the new United States.

A version of this map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

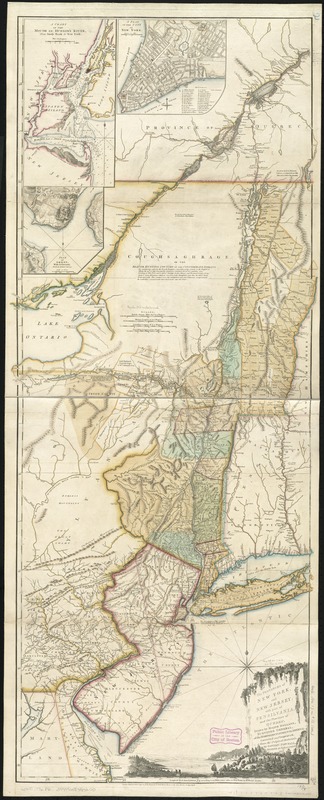

Thomas Pownall (1722-1805), after Samuel Holland (1728-1801)

The Provinces of New York and New Jersey, with Part of Pensilvania, and the Province of Quebec

London, 1776. Engraving, hand colored, 53 x 22 inches

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

Samuel Johannes Holland compiled the first map of New York published after the French and Indian War. Holland was a Dutch military engineer who became the Surveyor General for the Northern District in 1764. This map, first published in 1768, was based on maps and military surveys from the 1750s. The map was revised several times, resulting in this 1776 edition by Thomas Pownall, a Member of Parliament and former colonial administrator in New York and Massachusetts. The map’s vertical presentation and cartouche, which features an idyllic Hudson River scene, emphasizes the importance of the Hudson River-Lake Champlain corridor for fur trade with the Iroquois.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

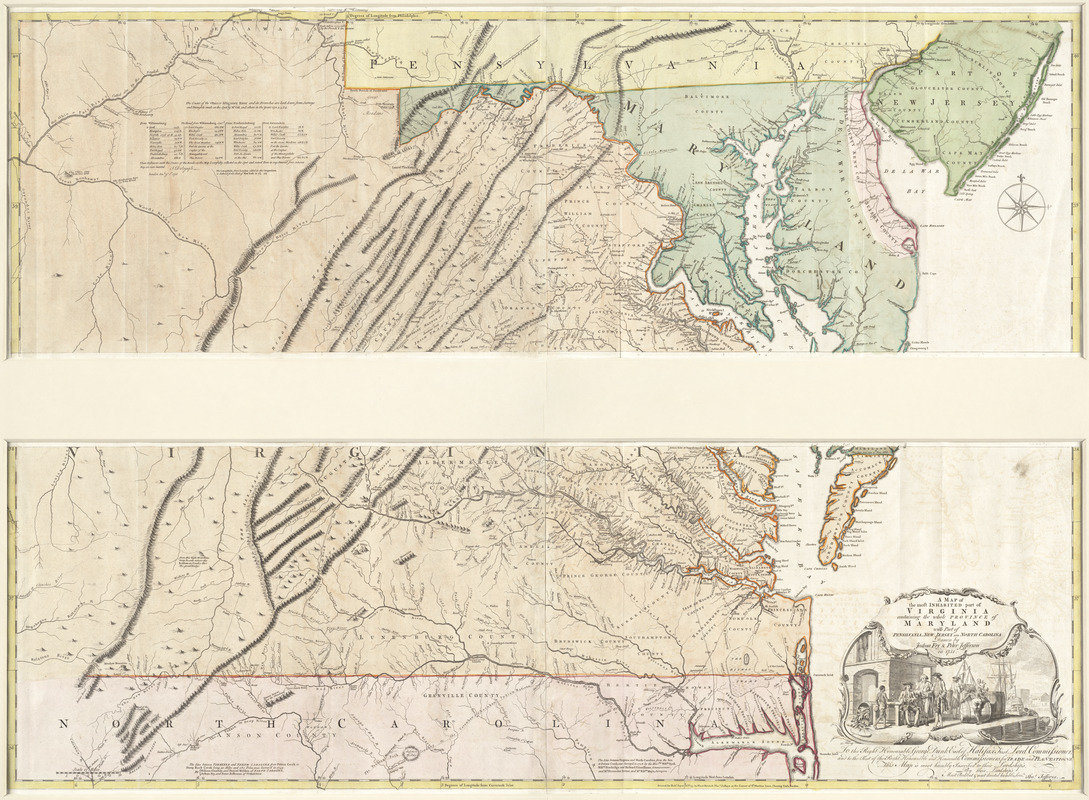

Joshua Fry (d. 1754) and Peter Jefferson (1708-1757)

A Map of the Most Inhabited Part of Virginia Containing the Whole Province of Maryland with Part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina, drawn . . . in 1751

London, [1768]. Engraving, hand colored, 44 x 49 inches

Courtesy of Richard H. Brown

Joshua Fry (Albemarle County surveyor) and his deputy, Peter Jefferson (Thomas Jefferson’s father), compiled this map in 1751 at the request of the Board of Trade. Based on their extensive experience surveying the Virginia-North Carolina boundary and Northern Neck Proprietary land grants, the map provided substantially new information about the mountain ranges and rivers in the western part of Virginia. This map remained the most authoritative map of the Chesapeake region for the rest of the 18th century, appearing in eight English and five French editions. John Mitchell used this map as he prepared his 1755 map of North America.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

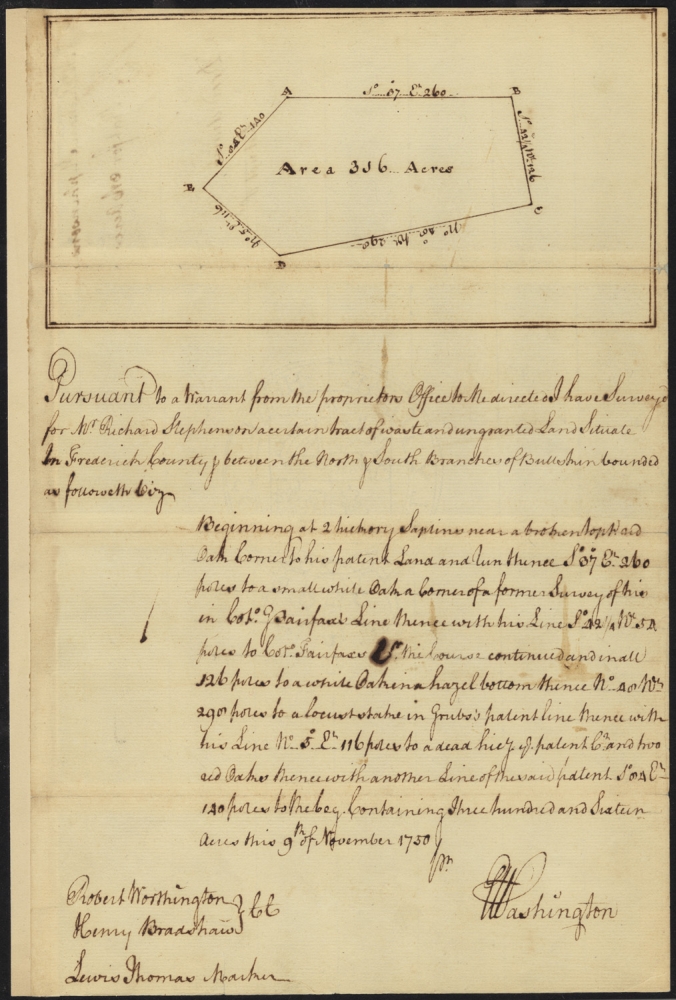

George Washington (1732-1799)

[Survey of Land for Richard Stephenson in Frederick County, Virginia]

November 9, 1750. Manuscript survey plat, 11.25 x 7.25 inches

Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Rare Books Department

Maps of individual colonies, such as the Fry and Jefferson map of Virginia, were compiled using the most accurate and recent information. They consulted published maps in combination with data from surveys of local geographical features, such as roads, rivers, or landholdings. This property survey by George Washington at age 18 is one example of these maps. This map is one of approximately 75 surviving surveys of the 199 that Washington completed during his career as a county surveyor. This survey documents 316 acres between the north and south branches of Bullskin Run, which is located in present-day Jefferson County, West Virginia.

John Dupee (1729-1773)

[Surveyor’s Compass and Chain]

Boston, ca. 1761-1773. Compass, engraved card, glass and wood housing, 9.5 x 4.75 x 7 inches

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

Mid-eighteenth-century surveyors, including George Washington, prepared simple cadastral or property surveys using a compass and chain. They determined angles or direction using a compass, such as this one, which was made by a Boston instrument maker.

Surveyors measured distance with an iron-link chain, consisting of 100 links or 66 feet. Measurements were expressed in poles or rods (1 pole or rod equals 16.5 feet), while the written descriptions recorded the survey’s “metes and bounds.” For example, Washington’s survey for Richard Stephenson lists such natural features as “2 hickory saplins” and “a white oak in a hazel bottom.”

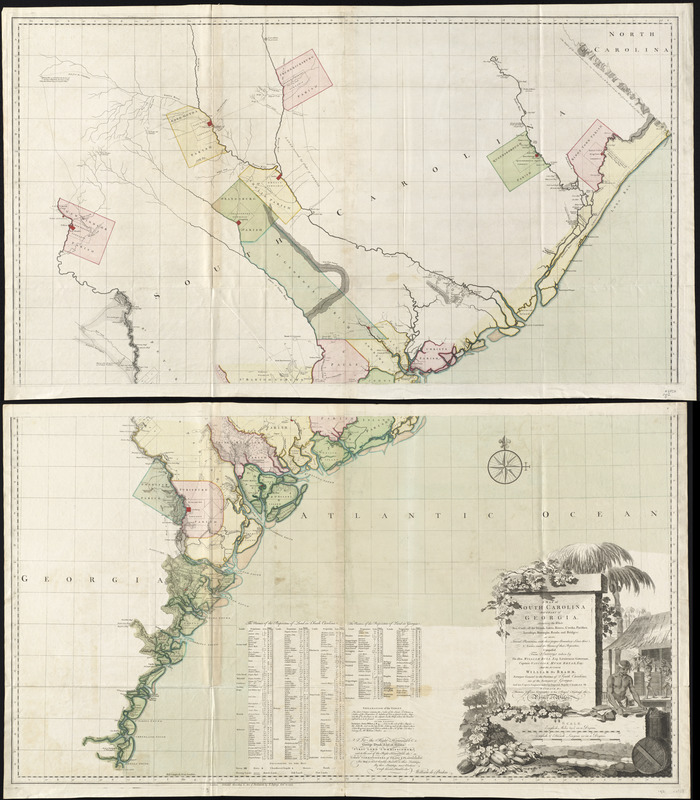

John Gerar William De Brahm (1717-1799)

A Map of South Carolina and a Part of Georgia

London, 1757. Engraving, hand colored, 52 x 47 inches

Courtesy of Richard H. Brown

De Brahm immigrated to the colonies from Germany in 1751 and became a surveyor in Georgia in 1754. He created this map of South Carolina and Georgia in 1757 using scientific topographical surveys. The economy of this region thrived on rice, indigo, and cotton and depended on the labor of slaves. New England slave owners tended to own a few slaves, but Southern plantations depended on a larger enslaved labor force. The cartouche in the bottom right features a scene of slaves at work. After the French and Indian War, De Brahm supervised the British coastal survey for the southern district.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

2.3 The French and Indian War

The French and Indian War comprised the colonial theater of Europe’s global Seven Years’ War. There Britain fought the French and Native Americans from 1754 to 1763. Each group wanted control of North America. The array of maps of North American battles includes maps of the campaigns to capture the St. Lawrence River Valley, Cape Breton Island, Lake Champlain, and the Ohio River Valley.

Britain’s victory greatly expanded her empire in North America. Under the 1763 Treaty of Paris, Britain acquired most of France’s territory in eastern Canada, Spanish-held Florida, and Native American land. Subsequently, the British military had to map these unfamiliar areas. These surveys complement a map locating British troops garrisoned in frontier regions to protect the new territorial acquisitions. Britain levied taxes on North American colonists, such as the Sugar Act and the Stamp Act, to support the troops, and forbade colonists from settling on western land reserved for Native Americans.

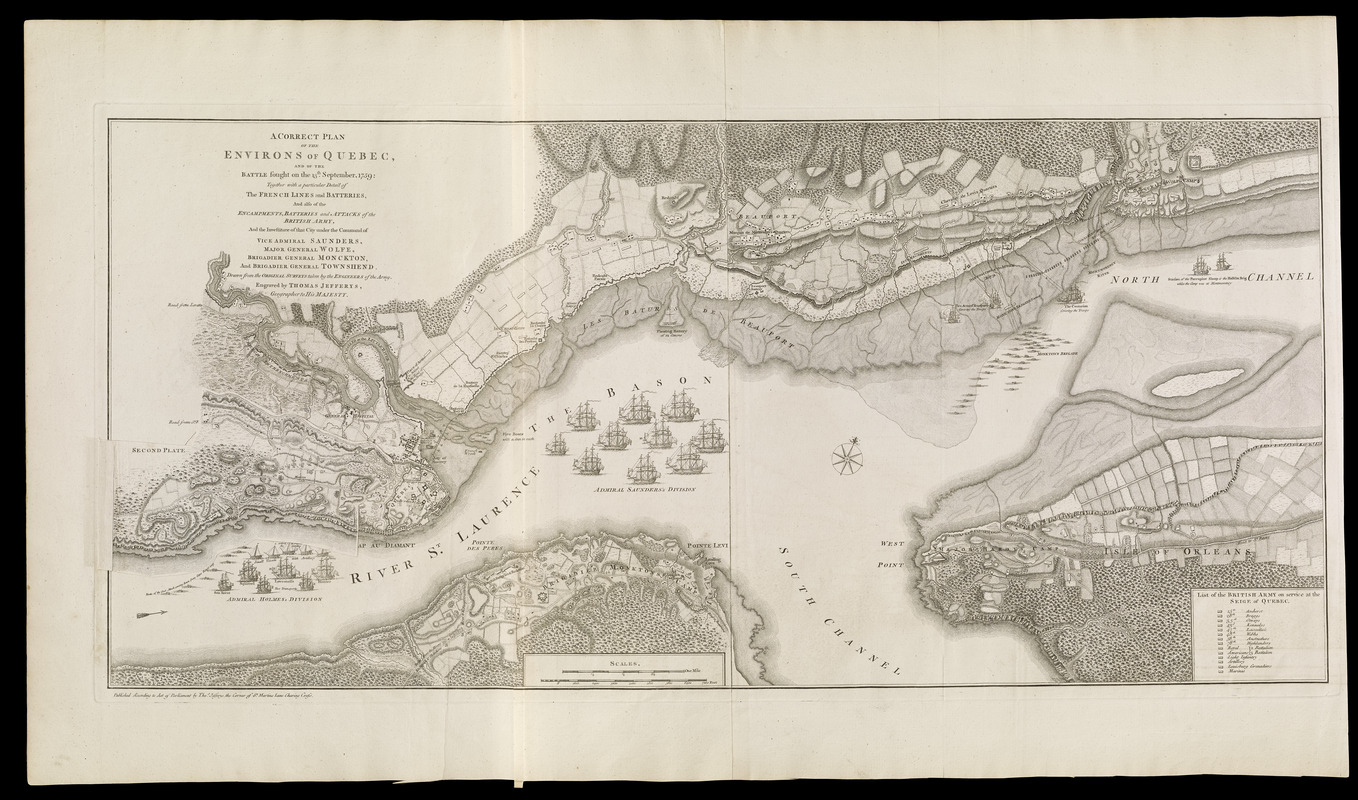

Thomas Jefferys (ca. 1710-1771)

“A Correct Plan of the Environs of Quebec and the Battle Fought on the 13th September 1759” in his A General Topography of North America and the West Indies

London, 1768. Engraving with overlay, 21.5 x 39.75 inches

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

Thomas Jefferys, one of London’s most prolific commercial map publishers during the mid-18th century, engraved this map of the 1759 siege of Quebec. It was included in his landmark atlas focused on North America and the West Indies. The atlas featured 93 maps documenting major battles during the French and Indian War and recent surveys of individual colonies. This after-battle map depicts the French lines and batteries as well as the encampments and batteries of the British army. Divisions of the British navy in the St. Lawrence River surround the city. This British victory facilitated British control of Canada after the war.

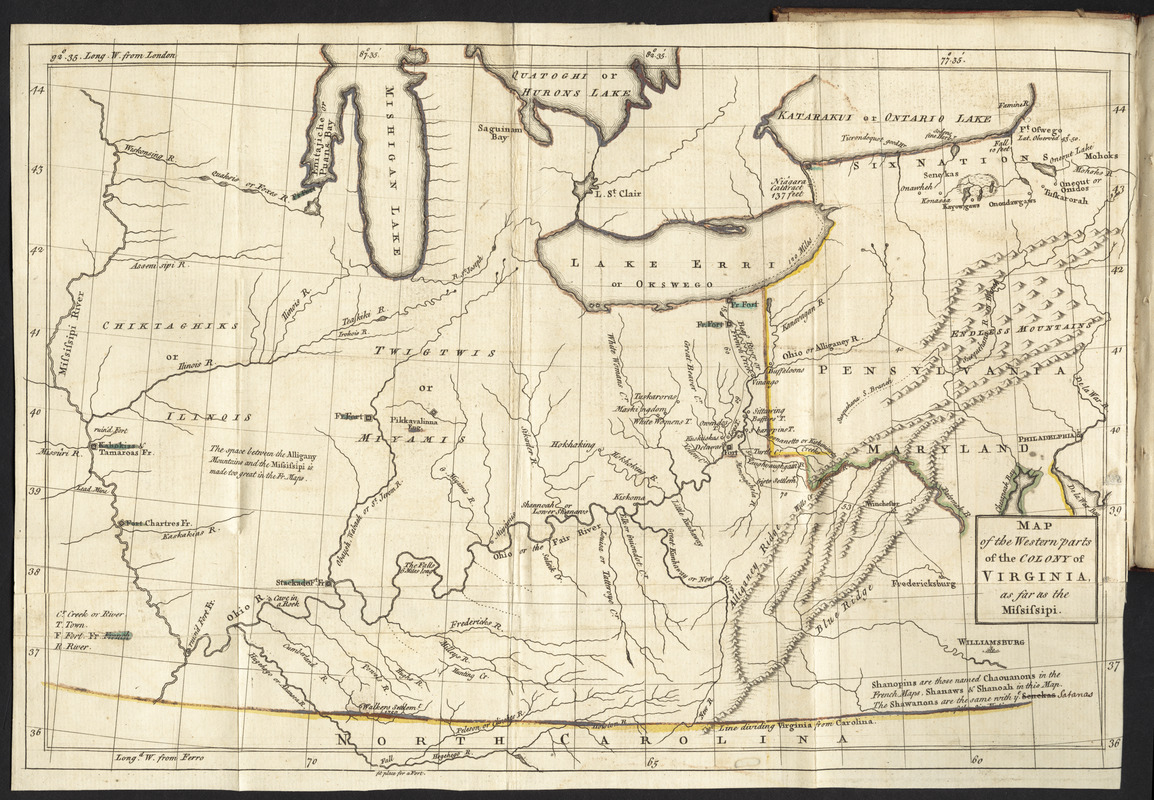

Thomas Jefferys (ca. 1710-1771)

“Map of the Western Parts of the Colony of Virginia, as Far as the Mississippi,” in The Journal of Major George Washington

London, 1754. Engraving, hand colored, 9.5 x 14.5 inches

Courtesy of Richard H. Brown

The London edition of George Washington’s journal, which recorded his 1753 military reconnaissance to Fort Duquesne and the Ohio River Valley, included this map of western Virginia and Pennsylvania. British General Edward Braddock led his unsuccessful 1755 campaign through this area at the beginning of the French and Indian War. The well-trained British troops, which included the young Washington, were soundly defeated by smaller, less-disciplined French and Indian forces at the Battle of the Monongahela. With Braddock and other British officers killed or severely wounded, Washington helped lead the retreat. Battle experience like this helped prepare him for leadership during the Revolutionary War.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

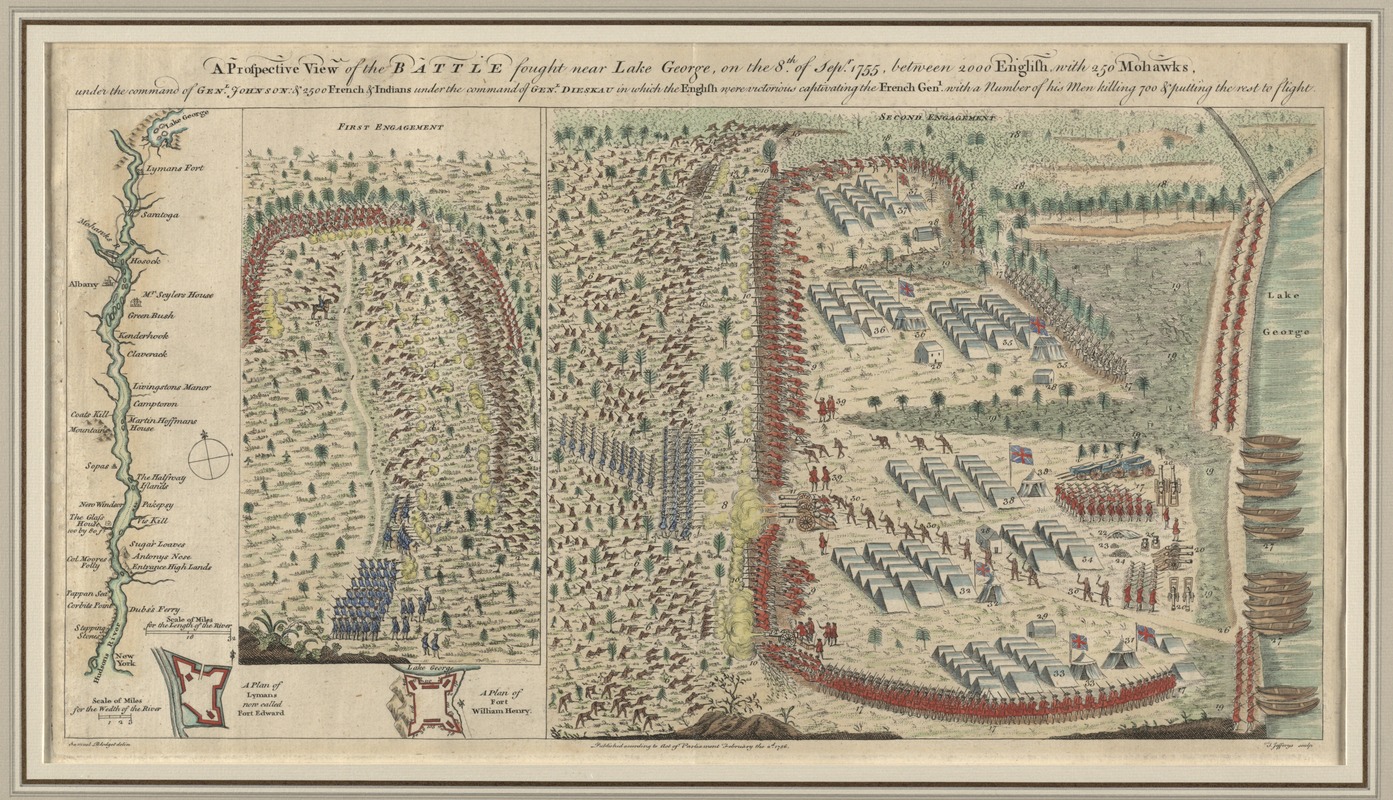

Samuel Blodget (1724-1807)

A Prospective View of the Battle Fought near Lake George

London, 1756. Engraving, hand colored, 10.5 x 20.5 inches

Courtesy of Richard H. Brown

British colonial troops wanted to capture Fort St. Frédéric (Crown Point), a French fortress on Lake Champlain, to gain control of the Lake Champlain corridor. Instead, they claimed victory at Lake George in September 1755. Samuel Blodget, a Massachusetts supplier to the troops, recorded these clashes based on his vantage point and eyewitness accounts. “The First Engagement” depicts the well-trained French troops, with Canadians and Native Americans, ambushing a hastily organized army of British colonists and Native Americans (including Mohawk Chief Hendrick). “The Second Engagement” depicts the failed French attack.

The Brave Old Hendrick the Great Sachem or Chief of the Mohawk Indians, One of the Six Nations Now in Alliance with & Subject to the King of Great Britain

[London, ca. 1740]. Engraving, hand colored, 14 x 10 inches

Courtesy of The John Carter Brown Library at Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island

Mohawk Chief Hendrick was killed while fighting with the British colonial troops at the Battle of Lake George in 1755. He appears on a horse on Blodget’s map, identified by the number three. Hendrick was a powerful leader within the Iroquois Confederacy. His leadership and alliance with the British helped the Mohawks maintain their political, economic, and military strength even as the British Empire grew. This portrait, printed in London, depicts him in a European-style military uniform, with a wampum belt in his left hand and a hatchet in his right. Contemporaries mentioned facial tattoos, which likely accounts for the markings on his face.

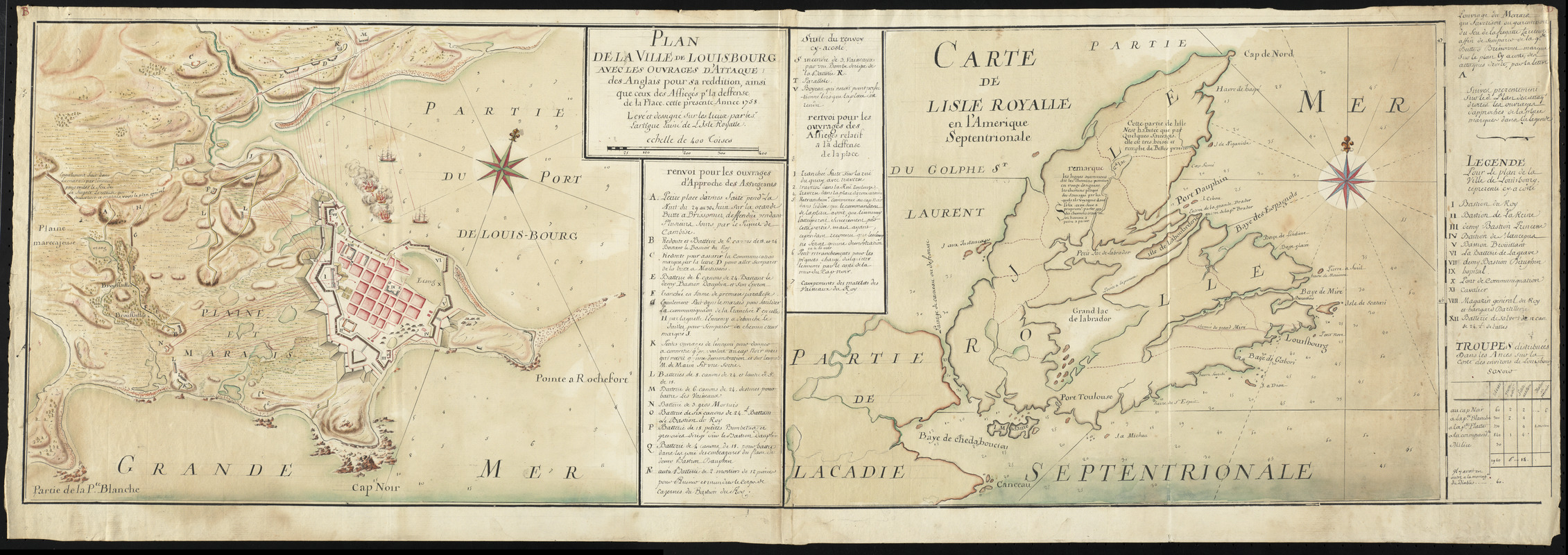

Pierre-Jérome Lartigue (1729-1772)

Plan de la ville de Louisbourg avec les ouvrages d’attaque des Anglais pour sa reddition and Carte de Lisle Royalle en l’Amerique Septentrionale

1758. Manuscript map, 14.5 x 42.5 inches

Courtesy of Richard H. Brown

During the early 18th century, Île Royale – present-day Cape Breton Island –became the home for displaced French settlers from Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. For their protection, the French constructed a massive citadel at Louisbourg. Beginning June 1, 1758, the British laid siege to the fort for six weeks. A decisive British victory at Louisbourg opened the St. Lawrence River for an attack on Quebec the next year. This pair of maps depicts the town, fortress, and island during the siege. Lartigue, a French-Canadian, prepared the maps 33 years before the first printed map was produced in Canada.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here and here.

Robert Sayer (1725-1794) and John Bennett (d. 1787)

A General Map of the Northern British Colonies in America: which Comprehends the Province of Quebec, the Government of Newfoundland, Nova-Scotia, New-England and New-York

London, 1776. Engraving, hand colored, 21 x 27 inches

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

Published at the beginning of the Revolutionary War, this map illustrates the territory that the British gained in Canada following the French and Indian War. It is based on the latest scientific surveys conducted in 1765, 1773, and 1774 by Samuel Holland, Surveyor General for the Northern District, as part of the General Survey of North America. Britain valued these former French colonies because the exportation of furs and cod fish generated sizable income for British merchants. The North American beaver atop the cartouche and the detailed depiction of the fishing banks off the coast of Newfoundland and Nova Scotia refer to these profitable resources.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

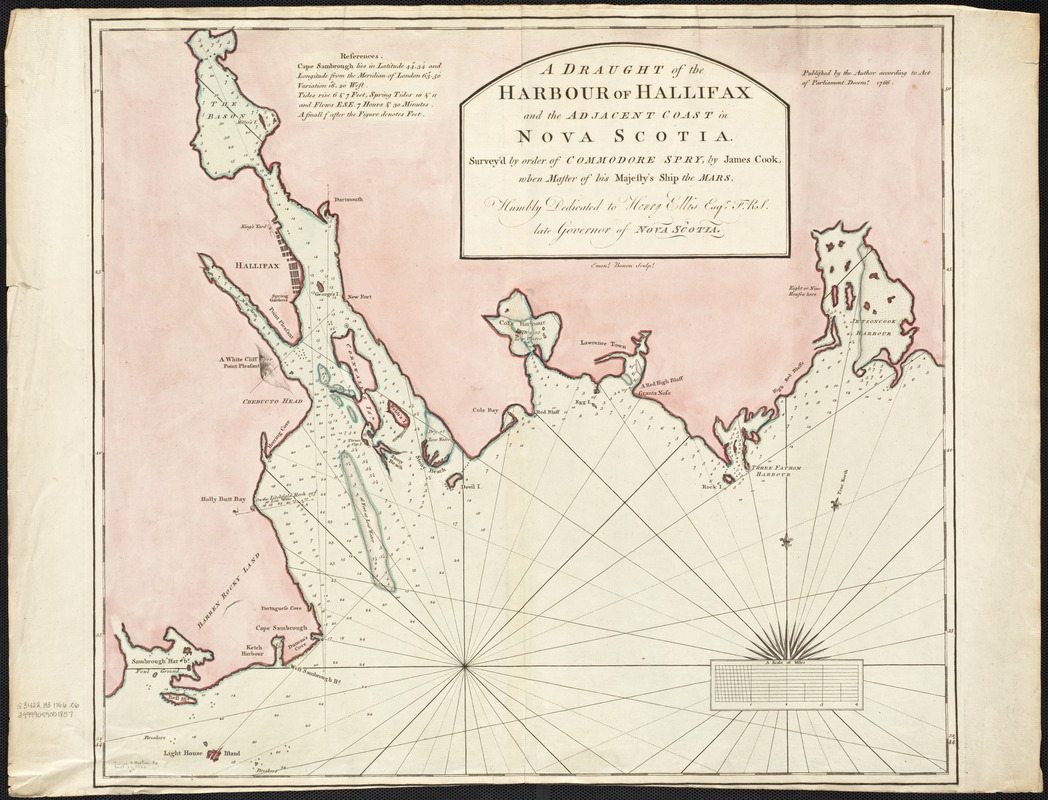

James Cook (fl. 1762-1775)

A Draught of the Harbour of Hallifax and the Adjacent Coast in Nova Scotia

London, 1766. Engraving, hand colored, 21 x 23 inches

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

Surveyor James Cook worked with Surveyor General Samuel Holland to map the new British territories in Canada after the French and Indian War. Cook created this map of Halifax in 1766. Previously, the fortress at Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island was the principal French settlement in Nova Scotia. During the French and Indian War, however, the British successfully used Halifax as a counterforce to Louisbourg. Halifax served as a British naval base throughout the war and became Nova Scotia’s major city and port after the British victory.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

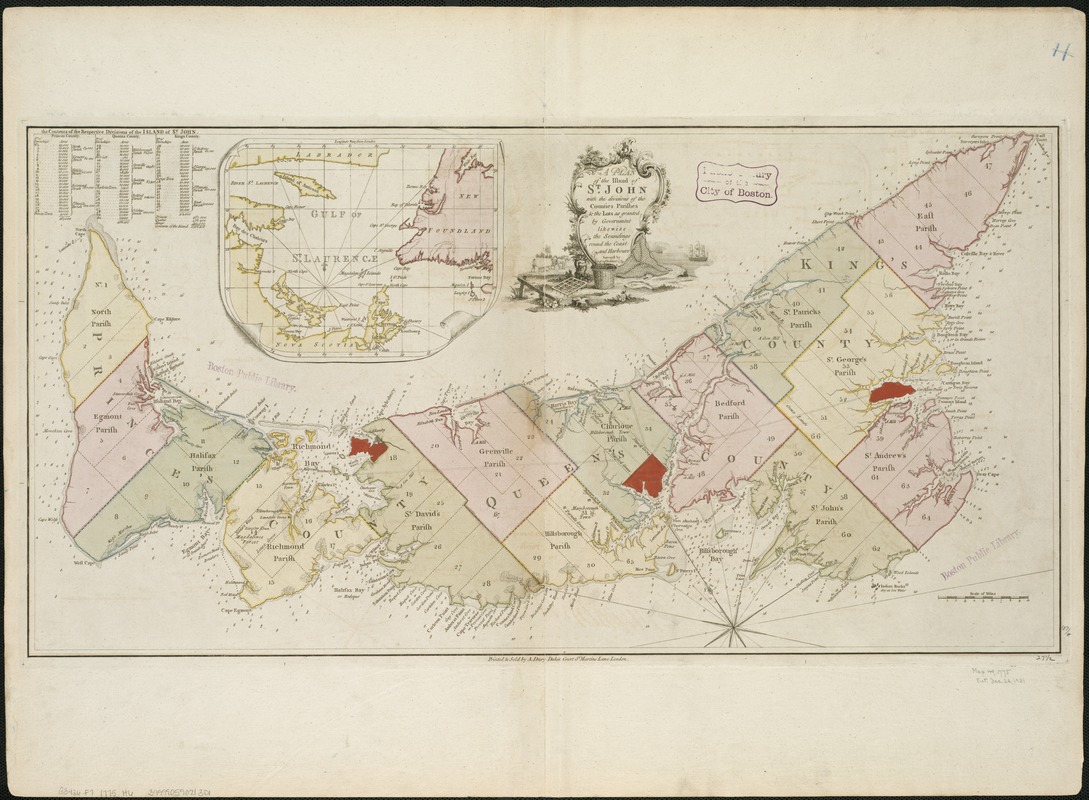

Samuel Holland (1728-1801)

A Plan of the Island of St. John with the Divisions of the Counties, Parishes, & the Lots as Granted by Government, Likewise the Soundings Round the Coast and Harbours

London, 1775. Engraving, hand colored, 14.5 x 28 inches

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

Following the French and Indian War, Samuel Holland conducted surveys for many of the charts of Britain’s new North American colonies published in the landmark maritime atlas The Atlantic Neptune. His first task for this project was a survey of St. John’s Island (modern-day Prince Edward Island). With explicit instructions from the Board of Trade, Holland divided the island into a grid-system of counties, parishes, and townships of uniform size. French and indigenous place names were changed to commemorate British royal figures. The shift to British names expressed the empire’s political control of the region and Holland’s loyalty to his patrons.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

William Stork (d. 1768)

A New Map of East Florida

London, 1767. Engraving, hand colored, 42.5 x 30.25 inches

Courtesy of Hillsborough County Collection, Tampa Bay History Center

Spain controlled Florida before the French and Indian War. During treaty negotiations, however, Spain offered Florida to Britain to regain control of Havana, which British troops had captured during the war. German botanist and writer William Stork created this map after visiting Florida in the late 1760s. His map gave the British a better understanding of their newly acquired territory. The map focuses on the east coast of Florida because Britain divided the peninsula into two colonies: east and west. Stork points out the fort at St. Augustine, the capital of East Florida, alongside other landmarks on the east coast.

William Brasier (1689-1775)

Plan of the Fortress and Dependent Forts at Crown Point with their Environs and Part of Lake Champlain

1759. Manuscript with water color, 32.5 x 44.75 inches

© The British Library Board, Additional Mss. 57713.4

British surveyor William Brasier prepared this plan after the British gained control of Fort St. Frédéric and nearby Fort Carillon (Ticonderoga) from the French in 1759. Both forts were located near the southern end of Lake Champlain. The French destroyed Fort St. Frédéric when they retreated to Quebec. After rebuilding and renaming it Crown Point, the British advanced to capture Quebec and Montreal.

In May 1775, colonial militia seized cannons from Ticonderoga and Crown Point, which were still garrisoned by British troops. They transported the cannons to Boston and positioned them on Dorchester Heights. The move helped force the British to evacuate in March 1776.

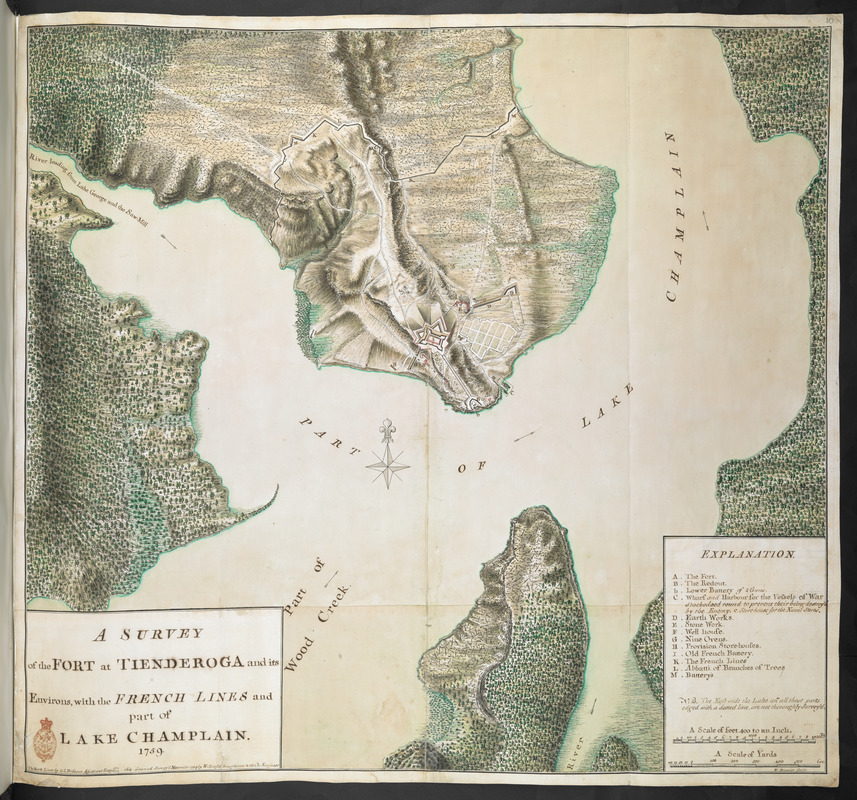

William Brasier (1689-1775)

A Survey of the Fort at Tienderoga and its Environs with the French Lines and Part of Lake Champlain

1759. Manuscript with water color, 27 x 29 inches

© The British Library Board, Additional Mss. 57712.10

British surveyor William Brasier prepared this plan after the British gained control of Fort Carillon and nearby Fort St. Frédéric (Crown Point) from the French in 1759. Both forts were located near the southern end of Lake Champlain. The French destroyed much of Fort Carillon when they retreated to Quebec. After repairing and renaming it Fort Ticonderoga, the British advanced to capture Quebec and Montreal.

In May 1775, colonial militia seized cannons from Ticonderoga and Crown Point, which were still garrisoned by British troops. They transported the cannons to Boston and positioned them on Dorchester Heights. The move helped force the British to evacuate in March 1776.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

Peter Tinges

[Powder Horn with Map of Hudson River, Lake George, and Lake Champlain]

Philadelphia, 1762. Scrimshaw horn, 15 x 2.5 x 2.25 inches

Courtesy of Fort Ticonderoga Museum

This powder horn from the 1760s belonged to Peter Tinges. It is decorated with a map of the Hudson River corridor that spirals around its length. A stylized representation of New York City appears at the base. The map identifies sites that were important during the French and Indian War, such as Saratoga, Fort Ticonderoga, Lake George, and Lake Champlain. The map represents a region populated with homes and forts as well as Native Americans, woods, and wildlife. The middle of the horn features the British royal coat of arms, referencing Tinges’ allegiance to the king.

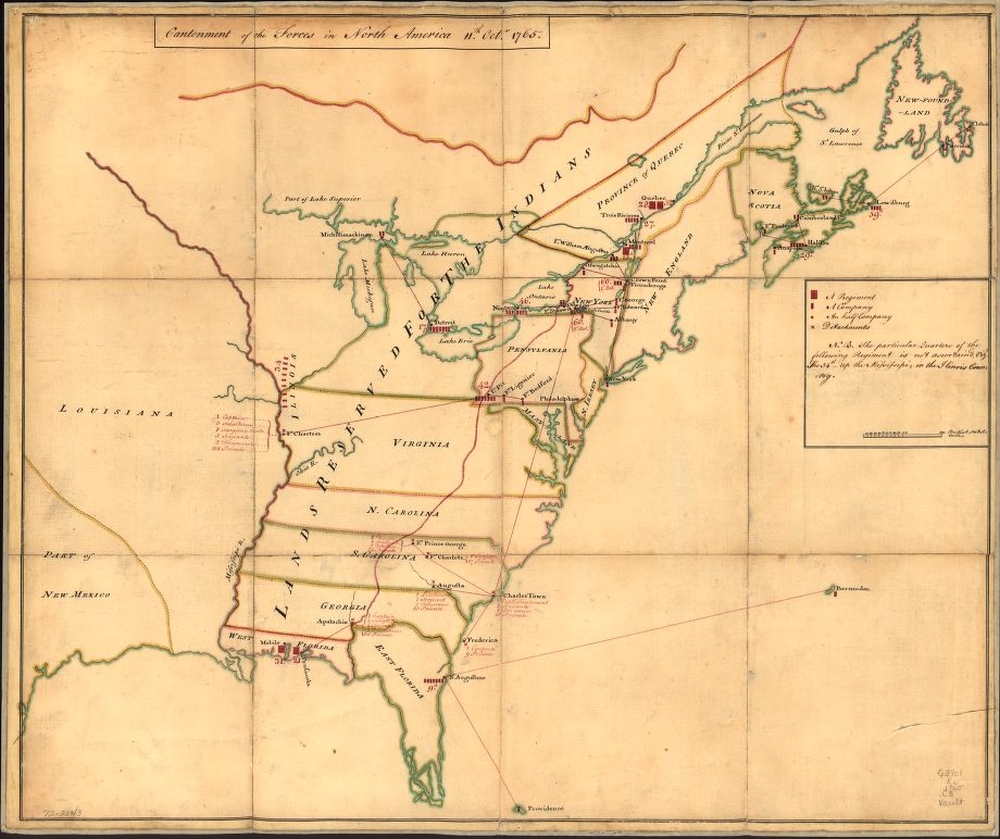

Cantonment of the Forces in North America 11th Octr. 1765

1765. Manuscript, pen and ink and watercolor, 20 x 24 inches

Courtesy of Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Cantonment of the Forces in N. America, 1766

1766. Manuscript, pen and ink and watercolor, 20.5 x 24.5 inches

Courtesy of William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan

Several manuscript maps drawn between 1765 and 1767 for the Quartermaster General show the placement of British troops in North America following the French and Indian War. As this example demonstrates, many soldiers remained in America after the war and were concentrated in the Northeast. The map features the 1763 Proclamation line as the western boundary for most colonies. Land west of this line was reserved for Native Americans, although colonists refused to follow this law. The British government levied new taxes, such as the Sugar and Stamp Acts, to pay for the war and continued military presence in this newly acquired land.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

3. The War for Independence

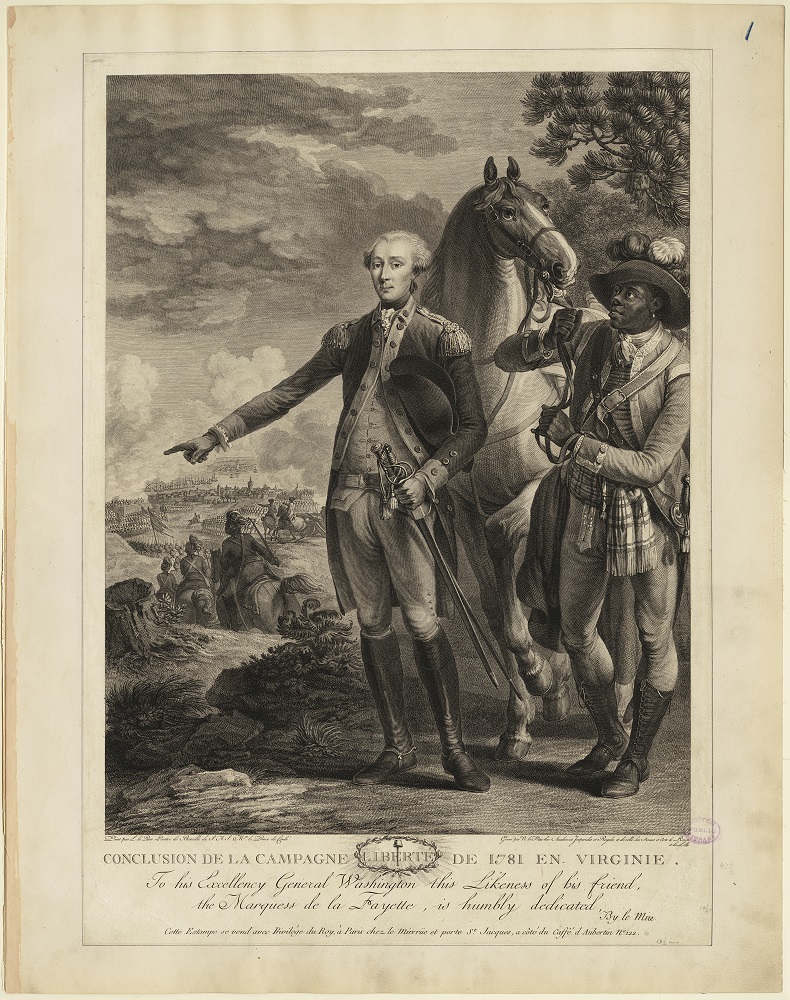

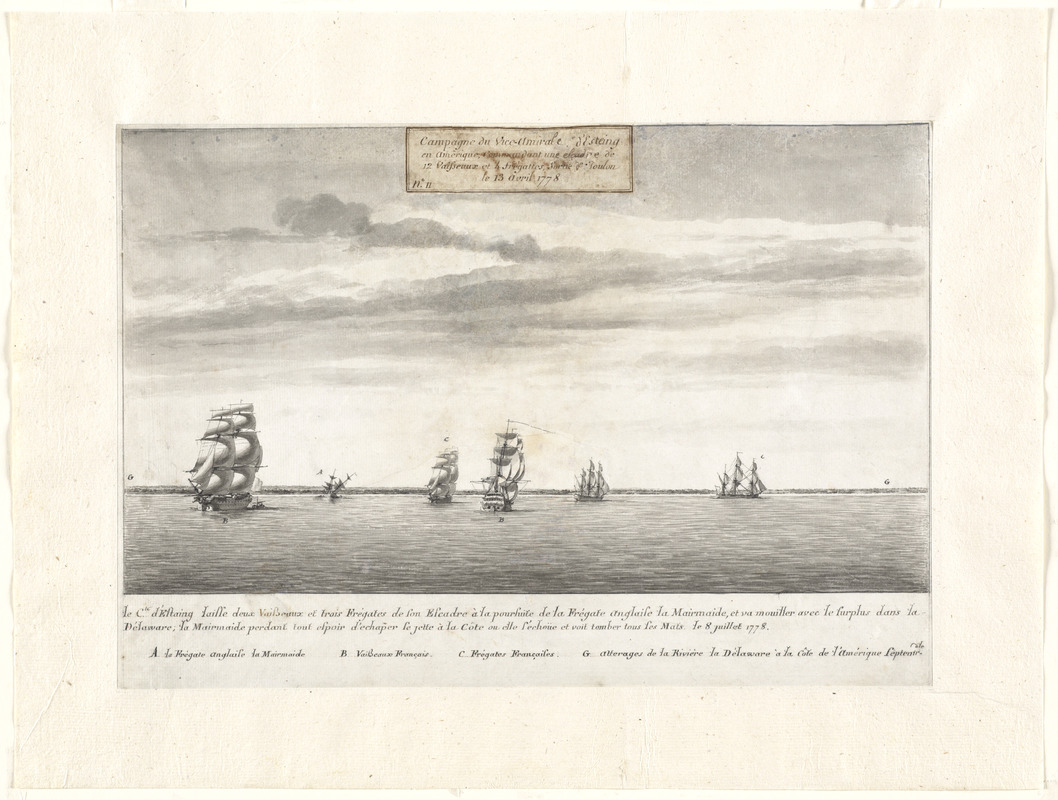

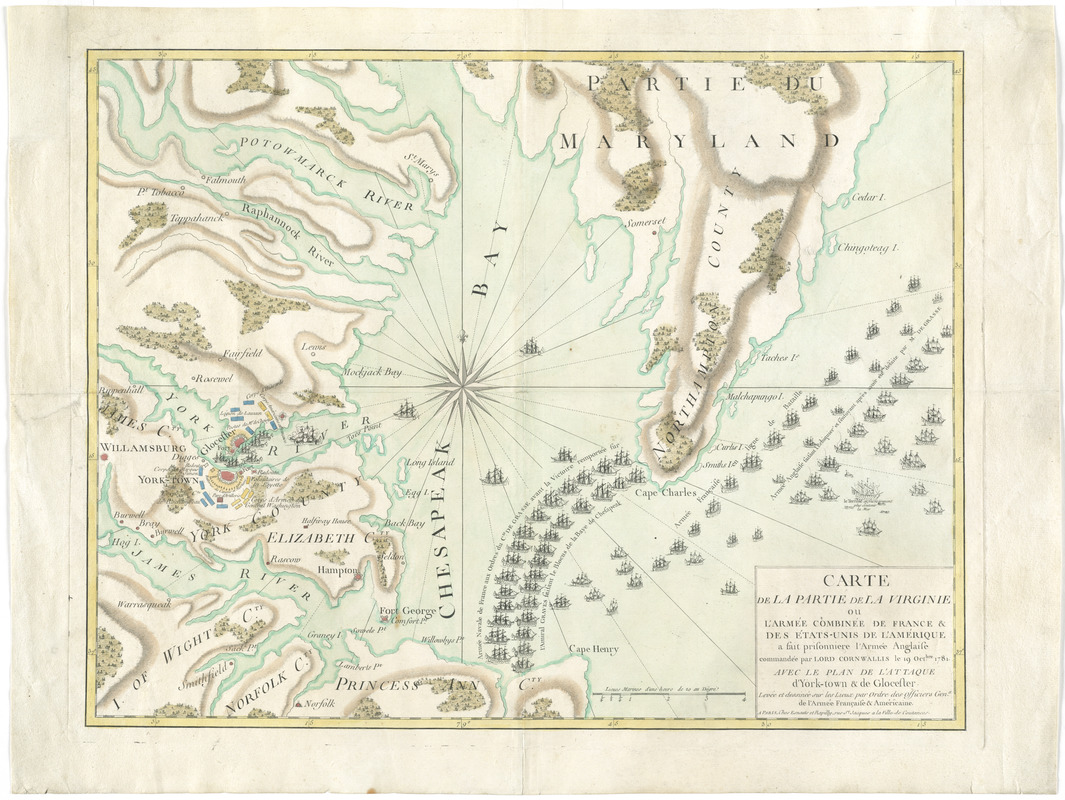

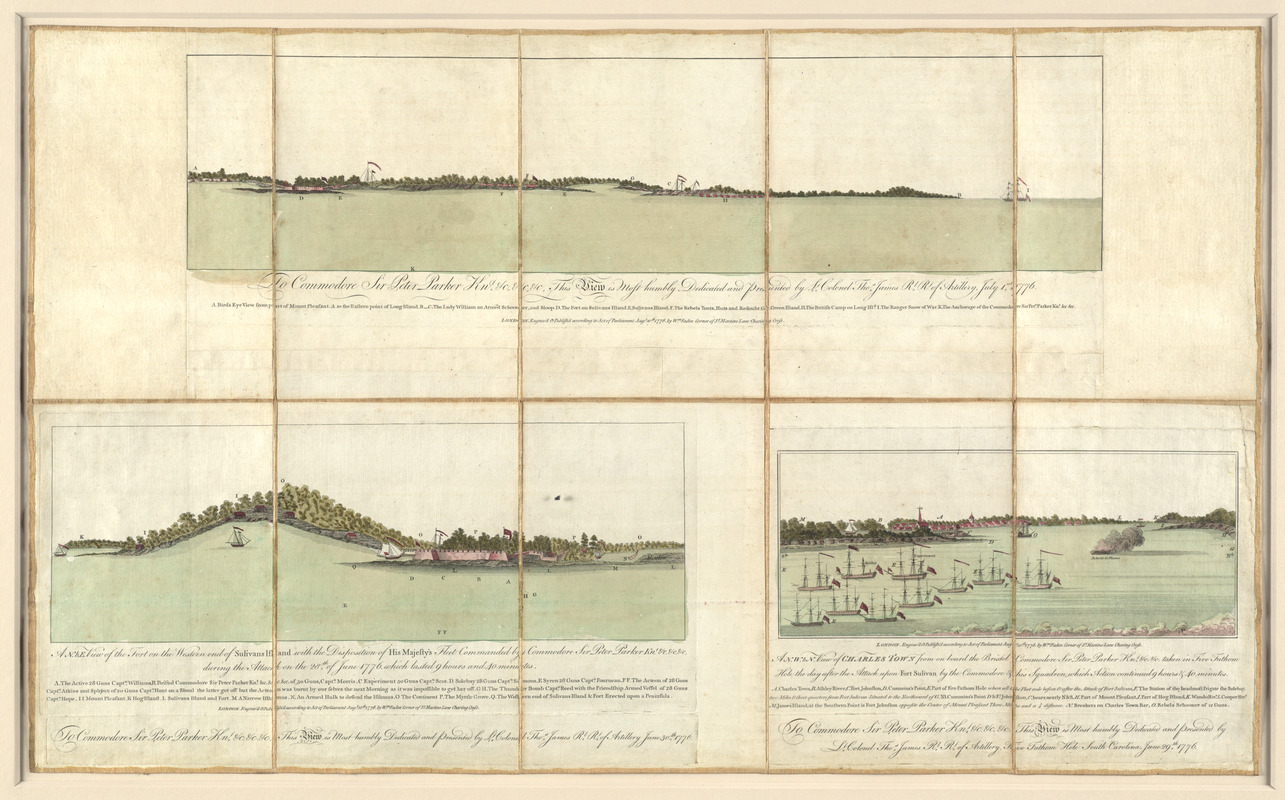

This section focuses on the years of the Revolutionary War, from 1775 to 1782. American histories of the Revolutionary War generally focus on landmark political events and broad military campaigns, highlighting important political and military leaders and their roles in conducting the war and the quest for independence. While Benjamin Franklin, Paul Revere, George Washington, John Adams, and Marquis de Lafayette are familiar names in this story, the exhibition also introduces military engineers and ordinary soldiers who participated in major military actions illustrated with a selection of printed and manuscript battle maps and related artifacts.

These objects convey stories about the ordinary soldiers who fought and died in the battles and the talented military engineers who prepared the maps. Their sacrifices began with the battles at Concord and Lexington outside of Boston and continued in far-flung arenas that included the Middle and Southern colonies and naval engagements in the West Indies. Soldiers’ powder flasks, for example, evoke the hands that once etched designs on oxen horns during lonely evenings in camp, and then reached for them in the panic of battle.

3.1 New England

The initial military actions of the Revolution took place in New England. British troops occupied Boston in 1768, and the first major battle occurred on April 19, 1775, when Rebel militia halted British troops marching to Concord and Lexington to capture Rebel munitions. Two months later the British narrowly defeated the Americans at Bunker Hill. Thereafter, British soldiers and American Loyalists were confined to Boston. George Washington’s Continental Army, meanwhile, fortified the surrounding area, including Dorchester Heights, where they brought cannons from Fort Ticonderoga to command Boston Harbor. Their strategy forced the British to evacuate on March 17, 1776.

During the remainder of the war, New England saw less military action than other regions. Newport, Rhode Island, however, continued to play an important role. British troops occupied Newport until 1779. French forces arrived the following year and used the port as a base for their military support of the Americans until the end of the war.

William Pierie (fl. late 18th century)

Plan and Views of the Capital of New England

1773. Manuscript with watercolor, 22.5 x 35 inches

© The British Library Board, King George III Topographical Collection, 120.34.

During the British occupation of Boston, Lieutenant William Pierie of the Royal Artillery drew this map of the city and the surrounding landscapes. Surveys like these provided the British with information about the geography of North America. Engravings of Pierie’s scenes appeared in The Atlantic Neptune, a maritime atlas used by the British Navy during the Revolutionary War. Pierie depicted geographical features that proved strategically important during the siege of Boston. George Washington’s soldiers, for example, would build fortifications on Dorchester Heights that helped force the British to evacuate.

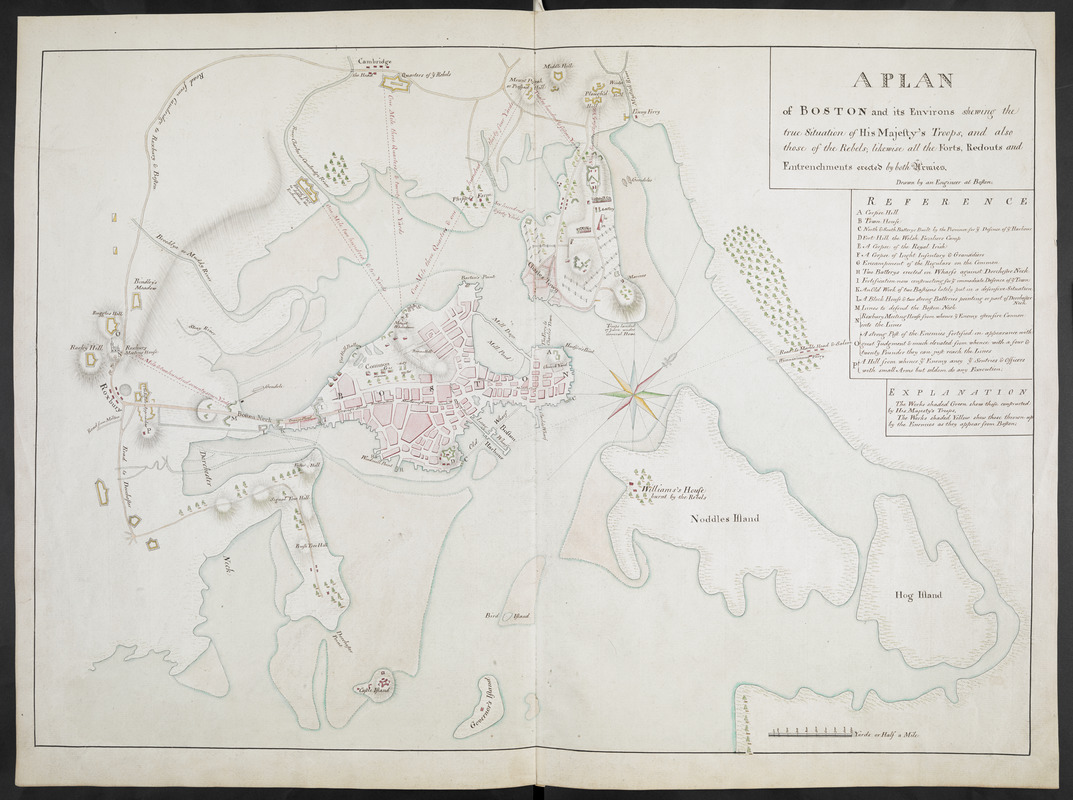

[Richard Williams] (active 1750-1776)

A Plan of Boston and its Environs Shewing the True Situation of His Majesty’s Troops and Also Those of the Rebels, Likewise All the Forts, Redoubts and Entrenchments Erected by Both Armies

1775. Manuscript, pen and ink and watercolor, 18 x 26 inches

© The British Library Board. Additional Mss. 15535.5

This map, probably drawn by British Lieutenant Richard Williams, depicts the positions of the British and American troops in October 1775. The map delineates the envelopment of the city by “rebel” forces that led to the British evacuation of Boston on March 17, 1776. Williams’s map features the Continental Army Headquarters in Cambridge and the fortifications constructed by American troops. His manuscript map was sent to London where it was engraved and printed less than two weeks before the British troops left the city. British military and political leaders used maps like this to gain a better sense of the American war.

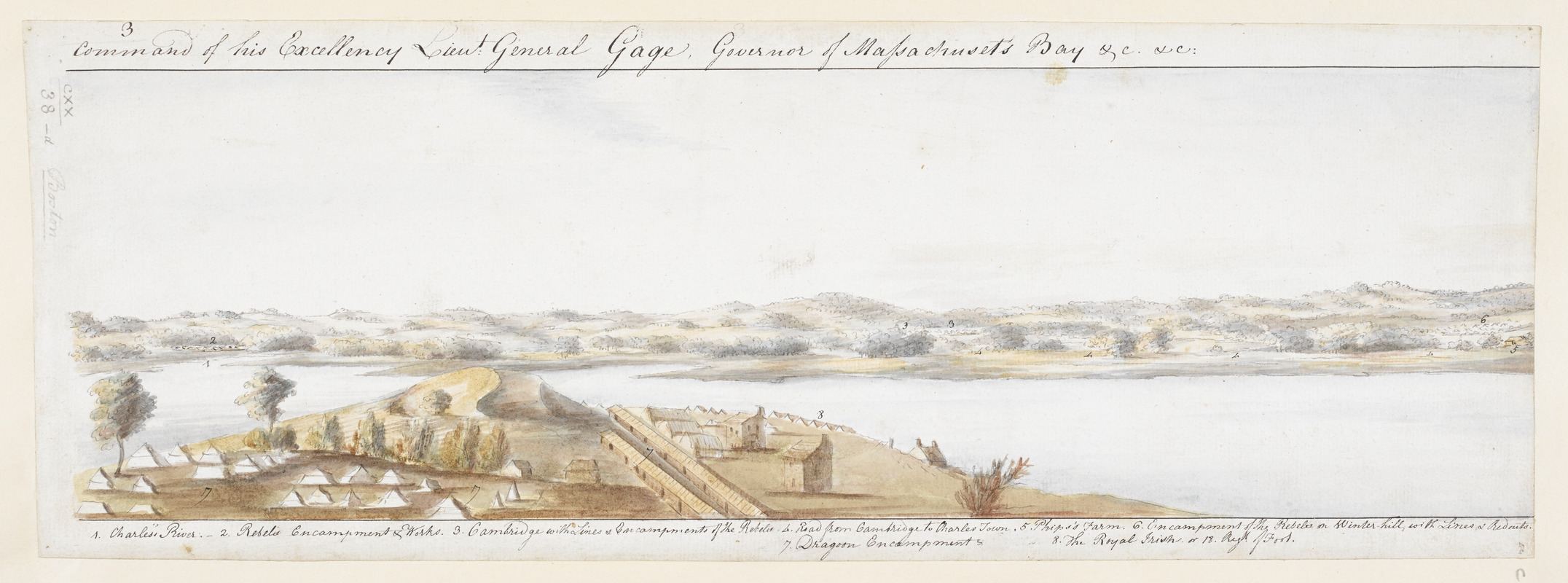

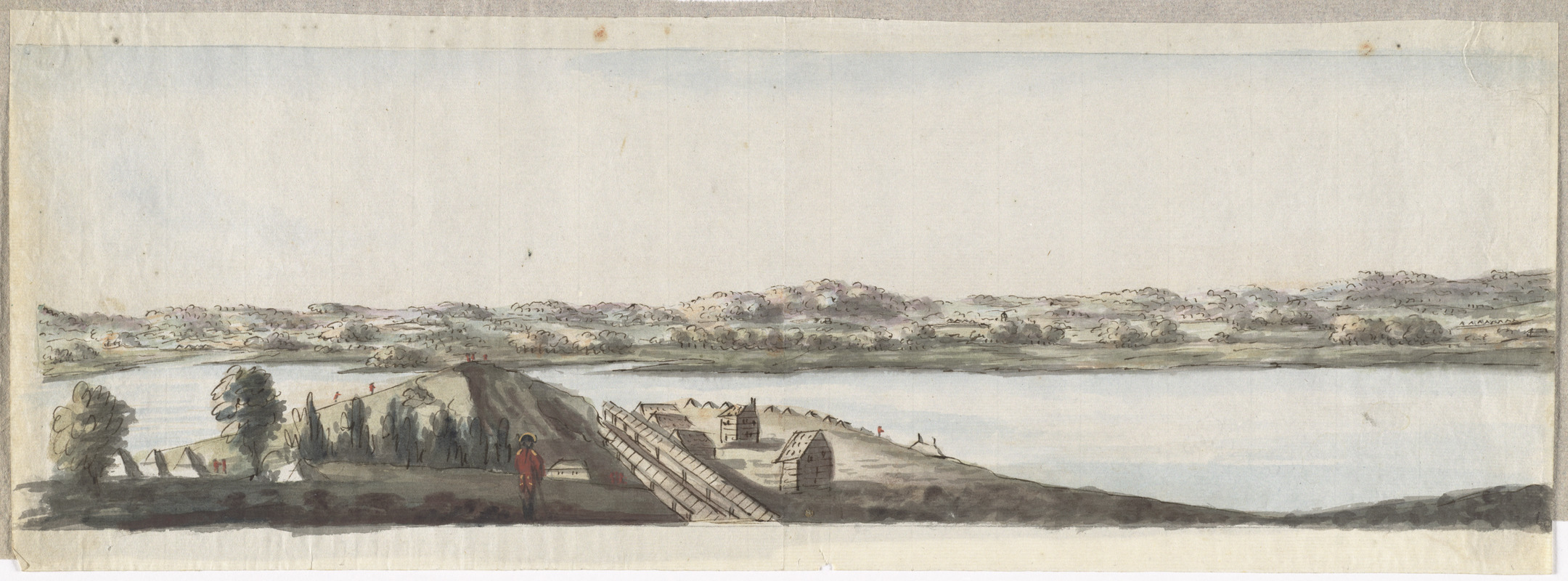

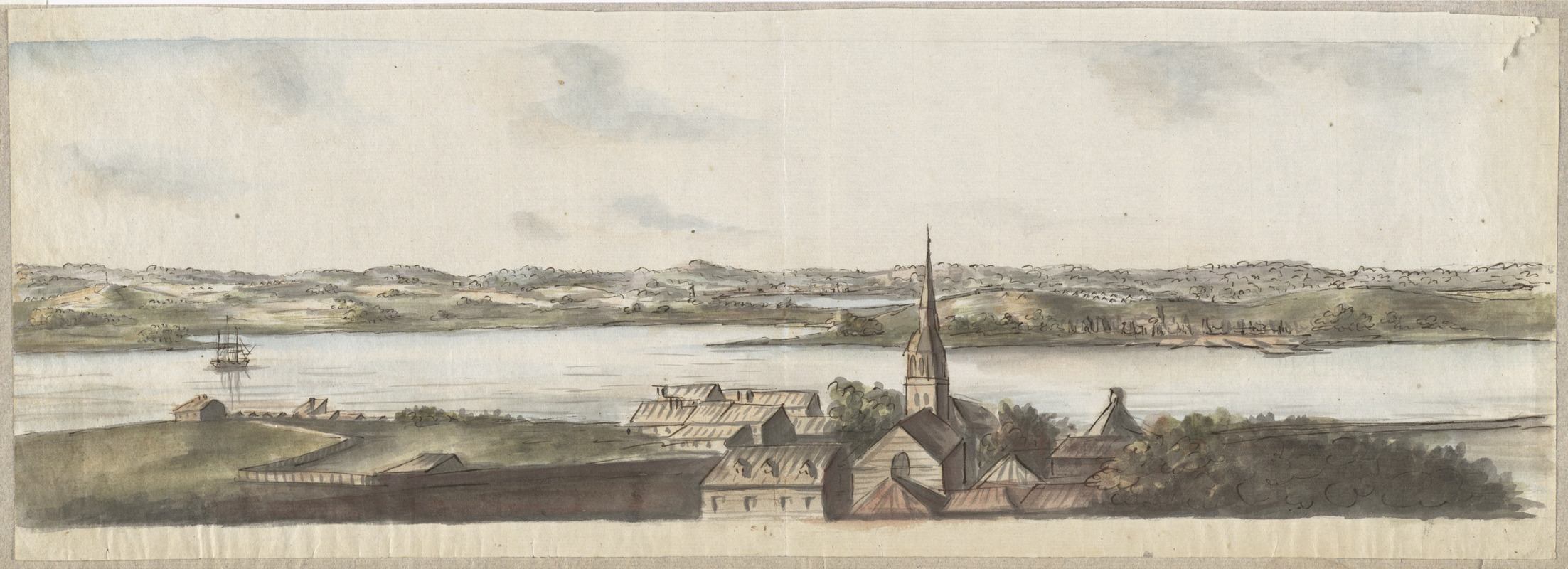

Richard Williams (active 1750-1776)

A View of the Country Round Boston, Taken from Beacon Hill…Shewing the Lines, Redoubts, & Different Encampments of the Rebels Also Those of His Majesty’s Troops under the Command of His Excellency Lieut. General Gage, Governor of Massachuset’s Bay

1775. Manuscript, ink and watercolor, each 7 x 19 inches

© The British Library Board, King George III Topographical Collection, 120.38

Richard Williams, a British lieutenant stationed in Boston during the siege, created these watercolor landscapes of the Boston countryside. In his journal, he described Boston as “well built.” But he observed that Boston suffered from neglect and had “grass growing in every street.” Williams drew five landscape views providing a panoramic perspective from Beacon Hill, and four are shown here. The first depicts a soldier looking toward Dorchester and Castle William (labeled “2”), which Williams described as having “a noble appearance.” The second features Declaration of Independence signer John Hancock’s house. The third depicts British encampments in the foreground with George Washington’s headquarters across the Charles River. The fourth scene features North Boston with the ruins of Charlestown, which burned during the Battle of Bunker Hill.

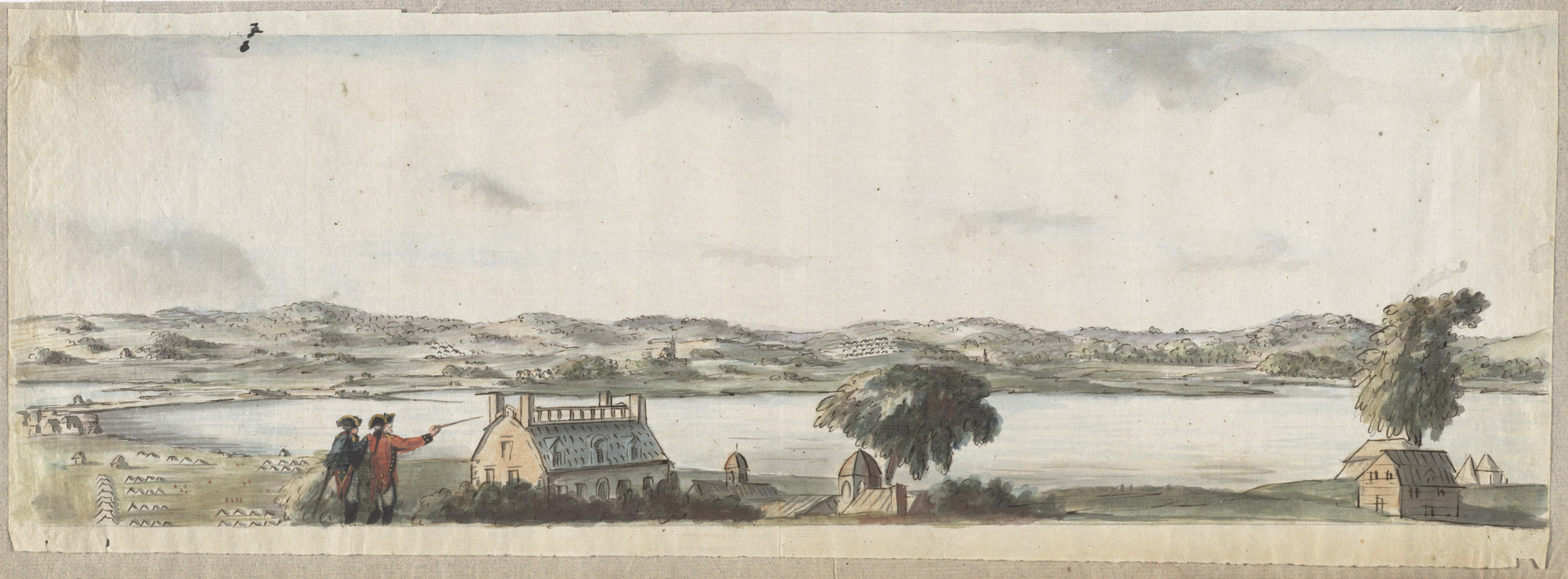

Richard Williams (active 1750-1776)

[A View of the Country Round Boston, Taken from Beacon Hill]

1775. Reproduction of original manuscript, ink and watercolor, 5 sheets, each 7 x 19 inches

Courtesy of Richard H. Brown

Richard Williams, a twenty-six year old British lieutenant, was stationed in Boston during the siege from 1775 to 1776. During this assignment, he created a set of five watercolor landscapes from Beacon Hill. They provide a panoramic view of Boston and the surrounding countryside. Another set of watercolors is displayed in the exhibition.

Pierre Simon Benjamin Duvivier (1730-1819)

[Congressional Gold Medal Awarded to George Washington]

Paris, 1789. Gold medal, diameter, 2.75 inches

Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Rare Books Department

In 1776 Congress voted to honor George Washington with a gold medal for ending the siege of Boston and forcing the British troops to evacuate. They commissioned a French engraver to create the medal, which was minted in 1789. On the hundredth anniversary of the evacuation, Bostonians purchased it from Washington’s heirs and donated it to the Boston Public Library. The medal features a profile of Washington on one side and a group of officers watching the British troops leave the city on the other. The profile portrait alludes to ancient Roman and Greek coins, artifacts of societies that influenced the new American government.

George Washington’s Gorget

Philadelphia, ca. 1774. Brass gorget, 5 x 2.25 x 1 inches

Collection of Massachusetts Historical Society

Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827)

George Washington as Colonel in the Virginia Regiment

1772, Reproduction of original, oil on canvas

Courtesy of the Washington-Custis-Lee Collection, Washington and Lee University, Lexington, VA

General George Washington owned this gilt brass gorget. A gorget was part of a protective suit of armor during the medieval period. By the eighteenth-century, it was a decorative piece worn as part of a dress uniform, a formal military uniform worn for special occasions. Artist Charles Willson Peale painted Washington wearing this gorget in his 1772 portrait, the only portrait of Washington from before the Revolutionary War. The gorget is engraved with the arms of the colony of Virginia. The Latin phrase “En Dat Virginia Quartum” acknowledges the colony was the fourth realm of the British Empire.

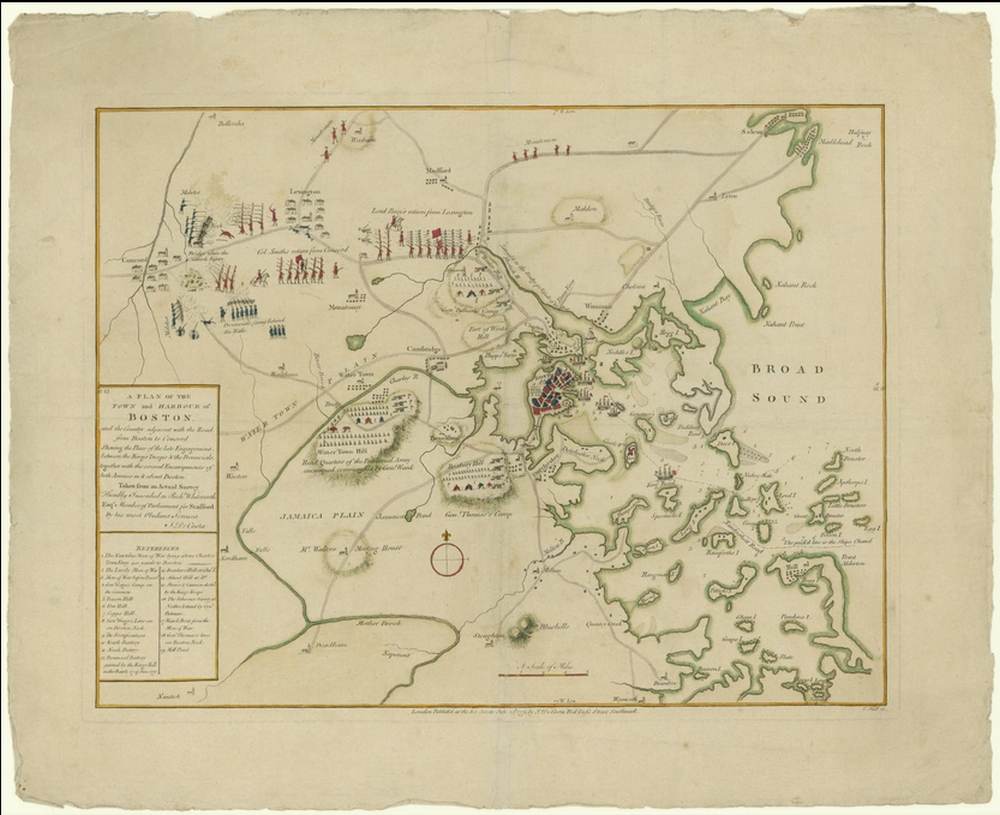

J. De Costa

A Plan of the Town and Harbour of Boston, and the Country Adjacent with the Road from Boston to Concord Shewing the Place of the Late Engagement between the King’s Troops & the Provincials

London, 1775. Engraving, hand colored, 15 x 19.5 inches

Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island

This map is recognized as the earliest battle map of the Revolutionary War. It uses pictorial symbols to document the battle between the British and colonists at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775. De Costa, the map maker, noted the “Bridge where the attack began,” highlighting the location of the first shots of the Revolutionary War. He also depicted the encampments, fortifications, and some weaponry for each side. British ships appear in the Boston harbor, and the key notes the types of ships. Printed in London and dedicated to a Member of Parliament, this map offered the British a better understanding of the conflict.

A version of this map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

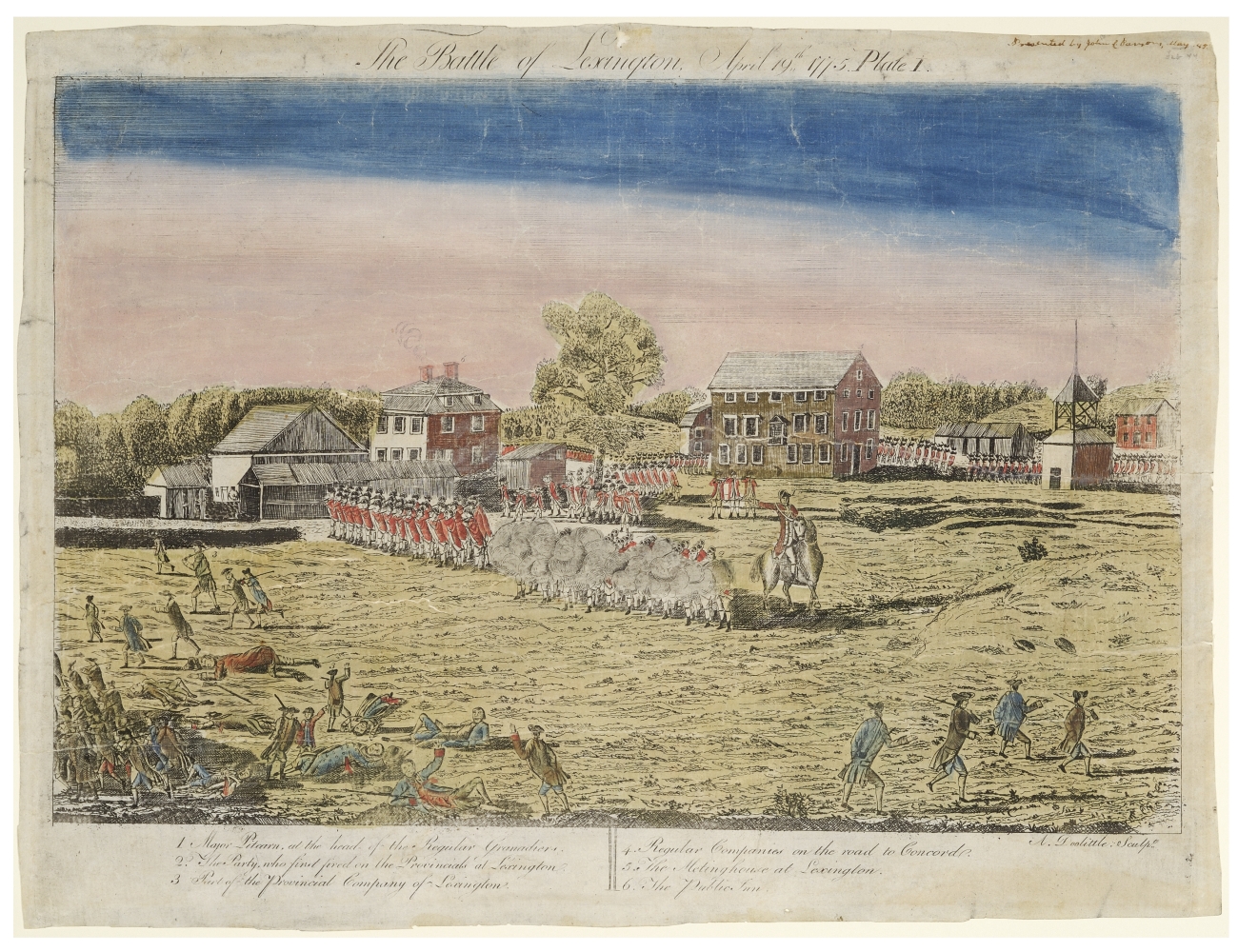

Amos Doolittle (1754-1832)

The Battle of Lexington, April 19th, 1775

New Haven, 1775. Engraving, hand colored, 13 x 17.5 inches

Courtesy of the Connecticut Historical Society, chs.org

Connecticut engraver Amos Doolittle created this view of the Battle of Lexington, the earliest clash between British and colonial soldiers. He paired this print with several other scenes from the conflict, including a view of Concord. Doolittle visited the sites soon after the battles and interviewed participants. His prints may be the most accurate representations of this conflict. This view features British soldiers standing in formation and firing on the colonists scattered in the foreground. Wounded colonists lie on the battlefield in distress while others flee. The town of Lexington appears in the background with the public inn and meetinghouse identified.

Amos Doolittle (1754-1832)

A View of the Town of Concord

New Haven, 1775. Engraving, hand colored, 13 x 17.5 inches

Courtesy of the Connecticut Historical Society, chs.org

Connecticut engraver Amos Doolittle created this view of Concord, the site of the earliest clashes between British and colonial soldiers. He paired this print with several other scenes from the conflict, including a view of the Battle of Lexington. Doolittle visited the sites soon after the battles and interviewed participants. His prints may be the most accurate representations of this conflict. This view features British soldiers marching into Concord. Some soldiers throw American arms into the millpond in the background, while others check local homes. Two British officers stand in the cemetery and use a telescope to view the nearby American soldiers.

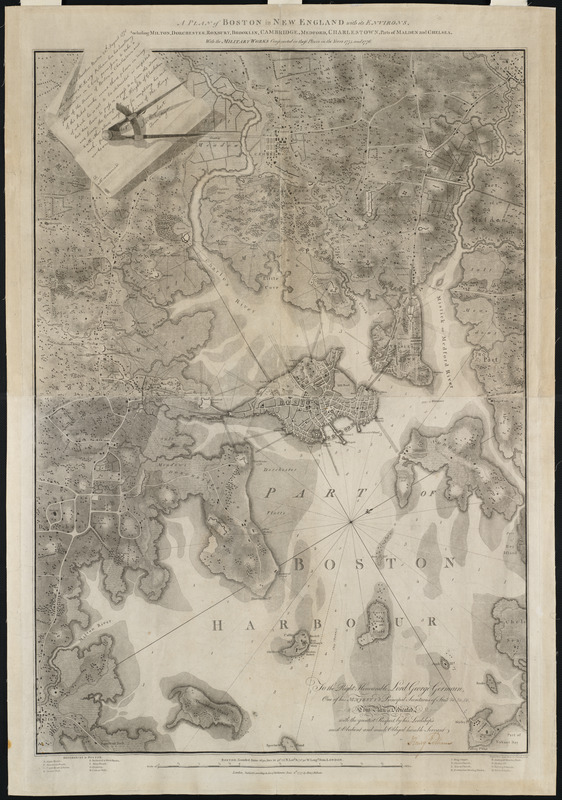

Henry Pelham (1749–1806)

A Plan of Boston in New England with its Environs, including Milton, Dorchester, Roxbury, Brooklin, Cambridge, Medford, Charlestown, Parts of Malden and Chelsea with the Military Works Constructed in Those Places in the Years 1775 and 1776

London, 1777. Engraving, 39 x 27.5 inches

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

Henry Pelham, a Loyalist, created this map of Boston in 1777, a year after the British evacuated the city. The map details the military fortifications in Boston and the surrounding areas. In the top left corner, Pelham included a copy of a note, dated two months after the Battle of Bunker Hill that gave him permission to see the “Rebel works.” Pelham also consulted his half-brother, the prominent portrait artist John Singleton Copley, about its production. Soon after Pelham completed it, he left America and joined Copley in England. Pelham’s map was the most detailed printed map of Boston and its environs to date.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

Bernard Romans (ca. 1720- ca. 1784)

An Exact View of the Late Battle at Charlestown, June 17th, 1775

London, 1776. Engraving, hand colored, 11.5 x 16.5 inches

Courtesy of Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Romans, recognized as one of the most talented cartographers in the southern colonies before the war, prepared this view of the “battle at Charlestown” or, as we know it, the Battle of Bunker Hill. He was born in the Netherlands and trained as an engineer in England. Romans came to America in 1756 in the service of the British government. During the war, he supported American independence. His popular—if romanticized—depiction of the Battle of Bunker Hill, labels key parts of the battle in the top margin. The number two, for example, identifies Charlestown, which British soldiers burned during their assault.

Thomas Hyde Page (1746-1821)

A Plan of the Action at Bunkers Hill, on the 17th of June 1775

London, 1778. Engraving, hand colored, 19.75 x 17.25 inches

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

Page, a military engineer who served as aide-de-camp to British General William Howe, prepared this plan of the Battle of Bunker Hill. This engagement occurred two months after the initial clashes at Lexington and Concord, and the British earned a costly victory over the Americans. Page delineated the redoubts, as well as other fences and hedgerows constructed by the Continental Army. The map also shows lines of fire from the British ships and the “Corps” (Copps) Hill battery. The plan features a separate overlay that depicts the changing positions of British troops during the course of the battle.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

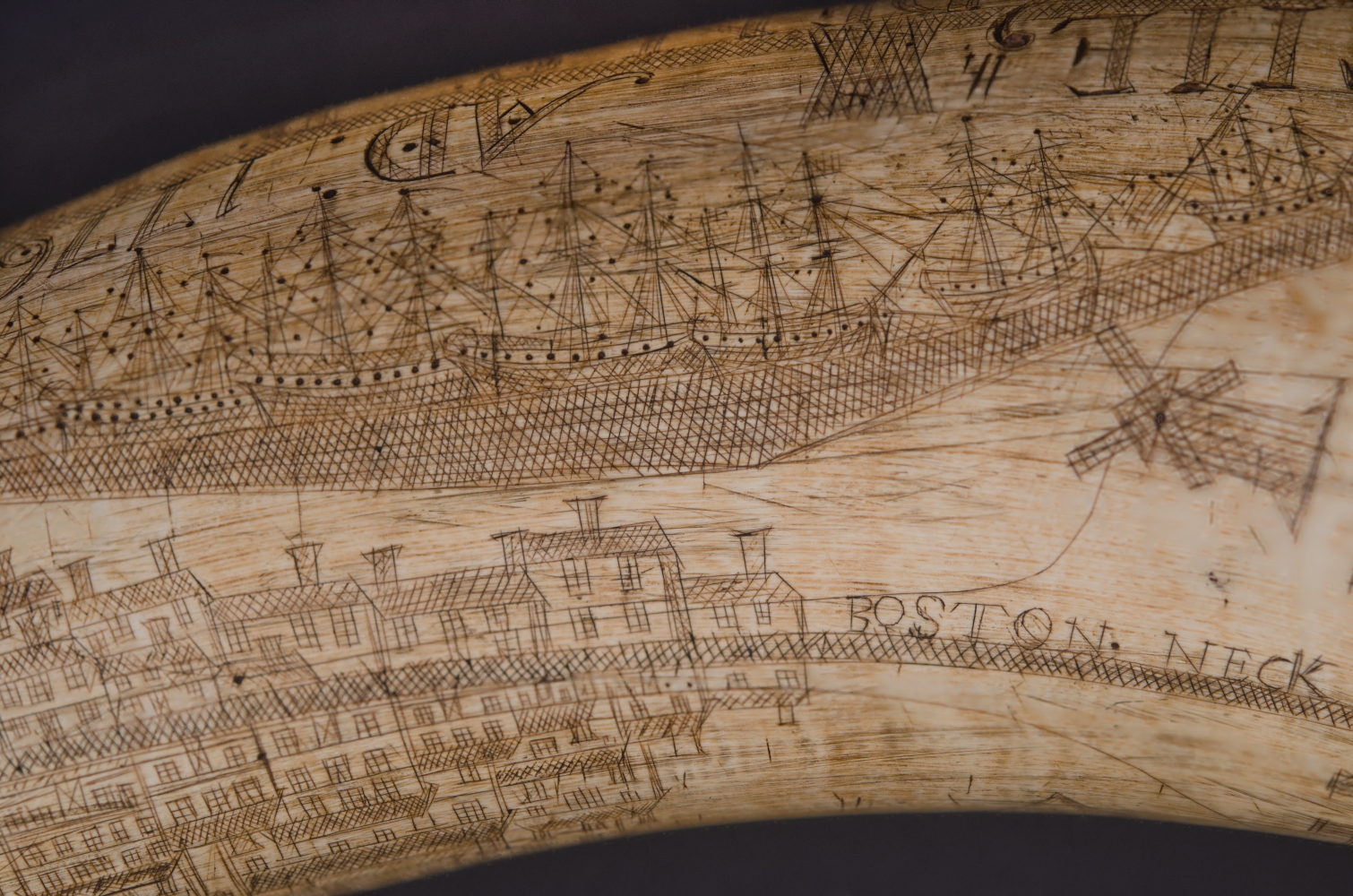

E.B.

[Powder Horn with Map of Boston and Charlestown]

[Boston], 1775. Scrimshaw horn, 14 x 3.5 x 3.5 inches

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

This powder horn, signed “E.B.” and dated 1775, was owned by a British soldier who was among the British troops occupying Boston from 1775 to 1776. The powder horn, which was used to hold gun powder, features a map of Boston and nearby Charlestown on one side. The soldier included a royal crown, alluding to his allegiance to the king, and a British man-of-war ship. He also proclaimed his hatred for the patriots on his horn: “A Pox on rebels in ther crymes [their crimes].”

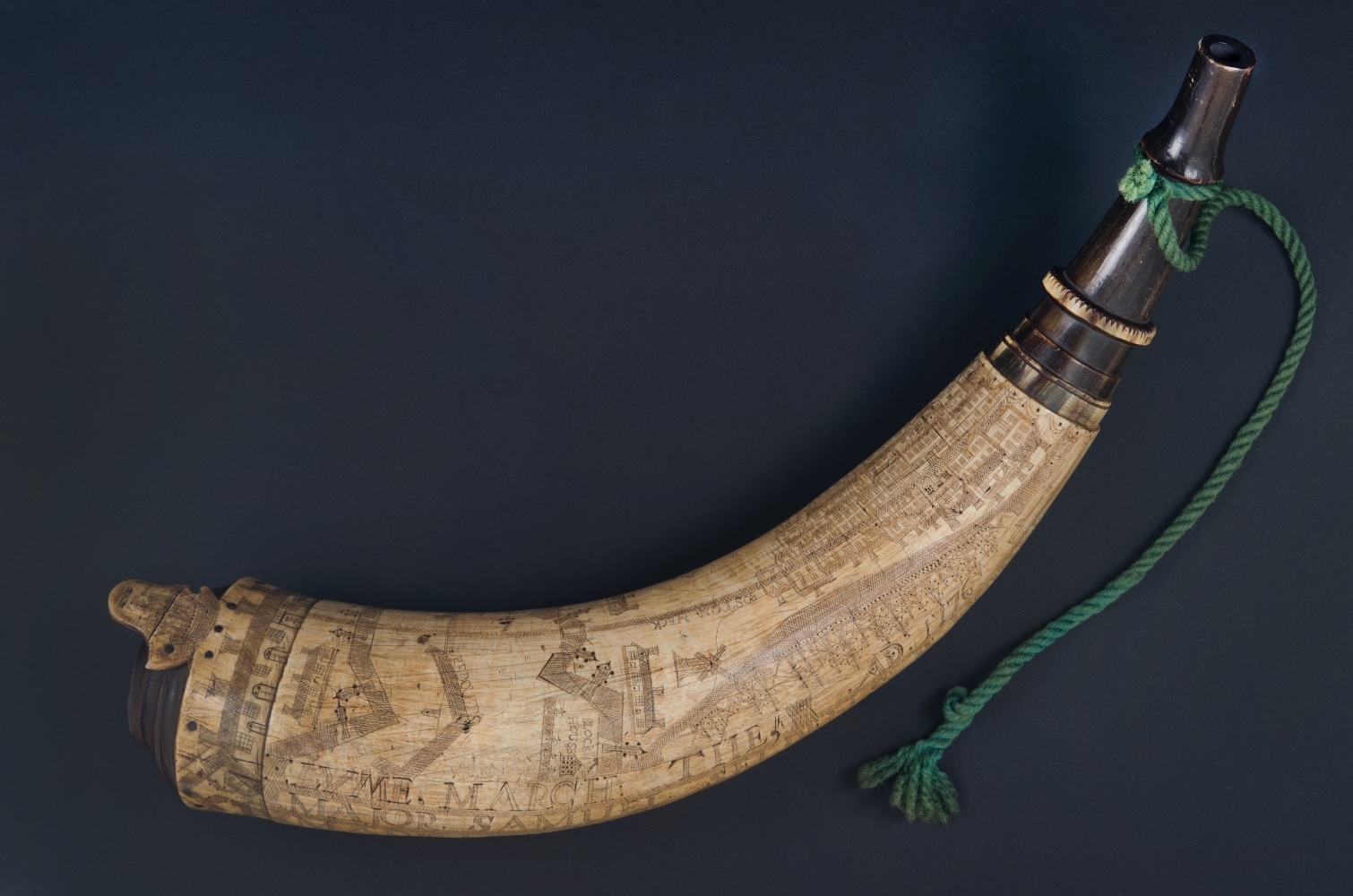

Samuel Selden (1723-1776)

Major Samuel Seldens P. Horn Made for the Defence of Liberty

Lyme, Conn., March 9, 1776. Scrimshaw horn, 14.5 x 8.5 x 5.25 inches

Collection of Massachusetts Historical Society

Samuel Selden, a prominent Connecticut farmer and patriot, owned this powder horn. He served with the Connecticut militia early in the Revolutionary War. His horn, inscribed during the siege of Boston in March 1776, depicts Continental Army fortifications and buildings in Boston as well as a fleet of ships. The largest ship, named “Amaraca,” displays a Liberty Tree flag on the masthead. Later that year, Selden was taken prisoner by the British army when the Americans evacuated New York City. He died on October 11, while still imprisoned.

Sword Said to Have Belonged to Gen. Joseph Warren

Late 18th century. Sword, brass, silver, and wood, 34 x 3.25 inches

Courtesy of Massachusetts Historical Society

This sword reportedly belonged to American General Joseph Warren, who died during the Battle of Bunker Hill. Warren was a prominent doctor and patriot political leader in revolutionary Boston. He was part of Boston’s Committee of Correspondence and sent Paul Revere and others to warn Americans about the march of British troops to Lexington and Concord. After his death, he became a martyr to the cause. His sword features a brass hilt with engraved silver rope designs. The blade is straight and double-edged. Floral designs and military trophies were etched on both sides of the blade.

French Flintlock Pistol

Late 18th-early 19th century. Walnut and iron, 11 inches

Courtesy of John M. Lewis

Revolutionary War soldiers used a variety of weapons. The most common was a muzzle-loading rifle, while swords and pistols, such as the ones displayed here, were most often used by officers. Pistols were considered a personal or secondary weapon. As single shot fire arms, they were time consuming to load. In addition, they were highly inaccurate, being most effective at a range of 15 feet or less. If all else failed, the grip, adorned with an iron butt cup, could be used as a club.

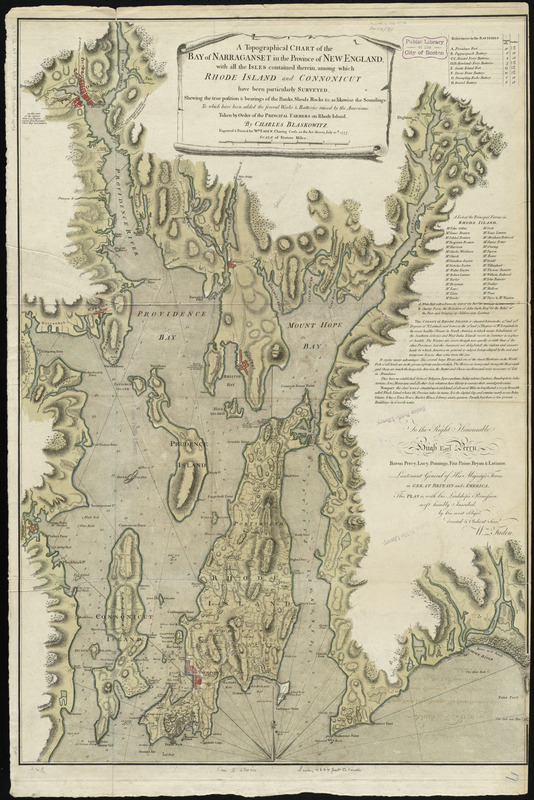

Charles Blaskowitz (ca. 1743-1823)

A Topographical Chart of the Bay of Narraganset in the Province of New England: with All the Isles Contained Therein, Among Which Rhode Island and Connonicut Have Been Particularly Surveyed

London, 1777. Engraving, hand colored, 36.5 x 25 inches

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

This topographical map of Narragansett Bay was based on surveys conducted in 1764 and 1774 by military engineer Charles Blaskowitz. Blaskowitz worked with Samuel Holland to survey the northern Atlantic coast. Londoner William Faden published this 1777 map when the British occupied Newport, Rhode Island. The following year, America’s alliance with the French faced its first test during the inconclusive Battle of Rhode Island. This map features the coastline and islands, locating individual farmsteads and towns. Marginal text praises Rhode Island for the “perfection” of its fish, and notes that residents are free to practice any religion they choose.

A version of this map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

3.2 Middle Colonies

After their evacuation of Boston, British troops relocated to New York City, where they remained until the war’s end. The British seized Manhattan and the surrounding counties during the fall of 1776. Then they focused on gaining control of the Hudson River Valley to connect with British troops in Canada. Although the British defeated the Americans at Lake Champlain, the Americans later declared a greater victory over British General John Burgoyne’s troops after the Battle of Saratoga.

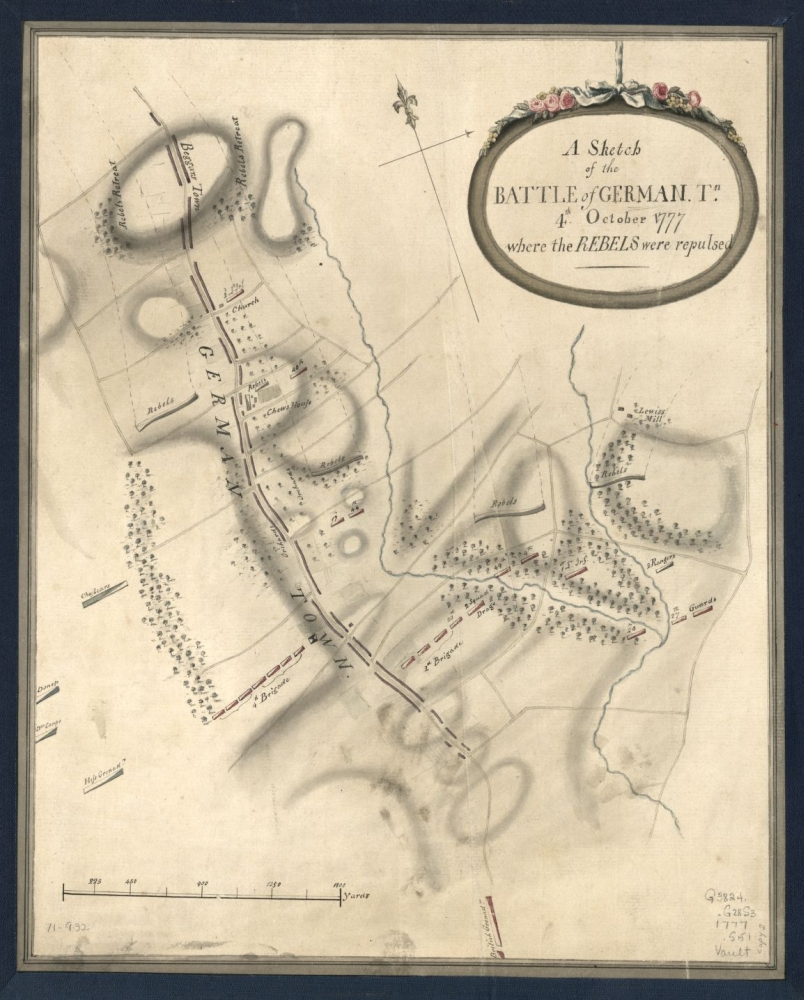

Meanwhile, Philadelphia became a focus of military activity throughout 1777 and early 1778. The city hosted the Continental Congress for the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Philadelphia was the seat of American government during the war, except during the British occupation of the city from September 1777 to June 1778. Like Philadelphia, nearby areas, including Trenton, Princeton, Brandywine, Germantown, and Monmouth, became battle sites.

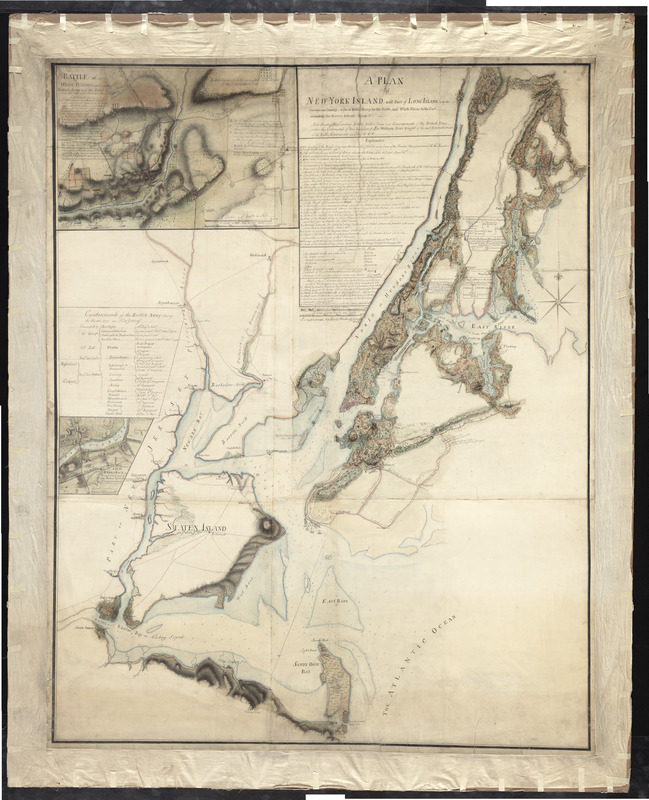

Charles Blaskowitz (ca. 1743-1823)

A Plan of New York Island, and Part of Long Island, with the Circumjacent Country, as Far as Dobbs’s Ferry to the North, and White Plains to the East

1777. Manuscript, hand-colored, 57 x 45 inches

Courtesy of Richard H. Brown

After evacuating Boston, the British focused their campaign on New York City. They took the city during the summer and fall of 1776. Charles Blaskowitz, one of the most accomplished topographical engineers in the British military, made this manuscript map for General Sir William Erskine, a participant in one of the battles portrayed. Blaskowitz documented the British military encampments and activities in the vicinity of New York City on this “Campaign Headquarters Map.” He combined specifics of key events overlaid on topography that was systematically surveyed, resulting in a map that is both comprehensive as well as aesthetically pleasing.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

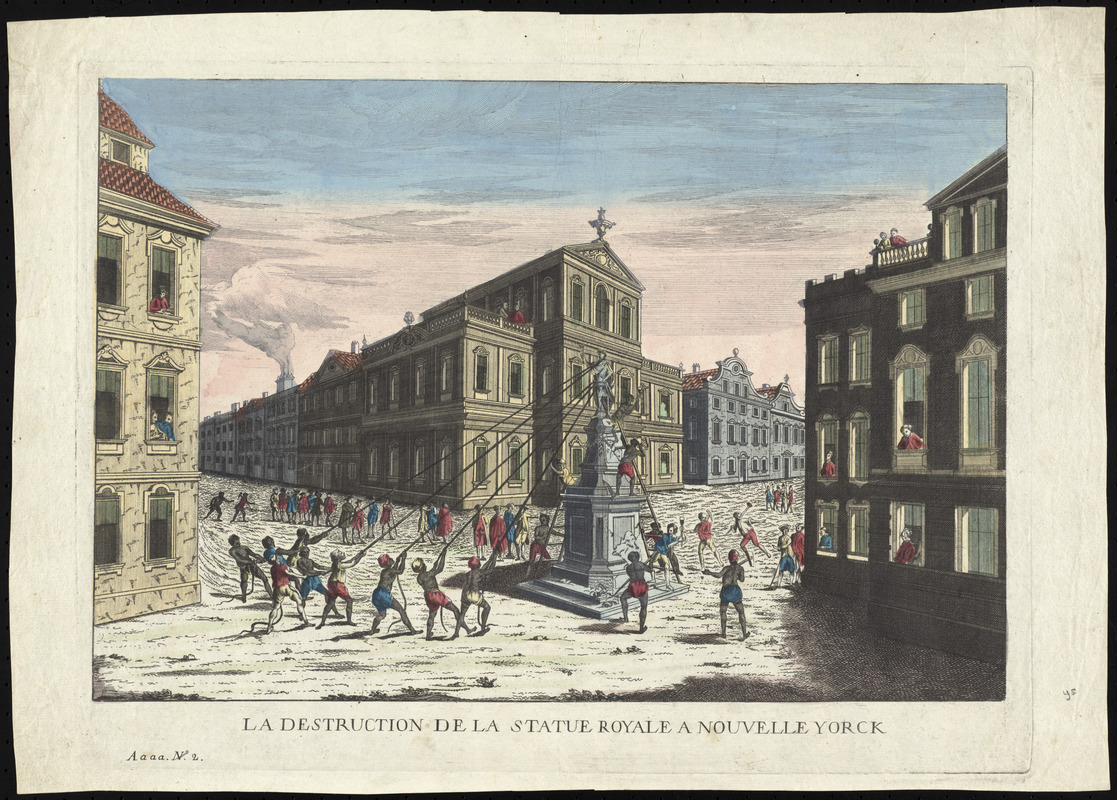

[André Basset?] (fl. 1749-1785)

La destruction de la statue royale a Nouvelle Yorck

[S.l., 1778?]. Optical view, etching, hand colored, 11.5 x 16.5 inches

Courtesy of Richard H. Brown

After George Washington read the Declaration of Independence to his troops in New York City on July 9, 1776, locals pulled down a statue of King George III. This European print imagines what the scene looked like. New Yorkers join with enslaved or freed Africans to take down the statue. People gather at the windows and on balconies to view the spectacle. The destruction of the statue by the people represented America’s challenge to monarchical tyranny. Consumers viewed this print through a set of lenses to give dimension to the image.

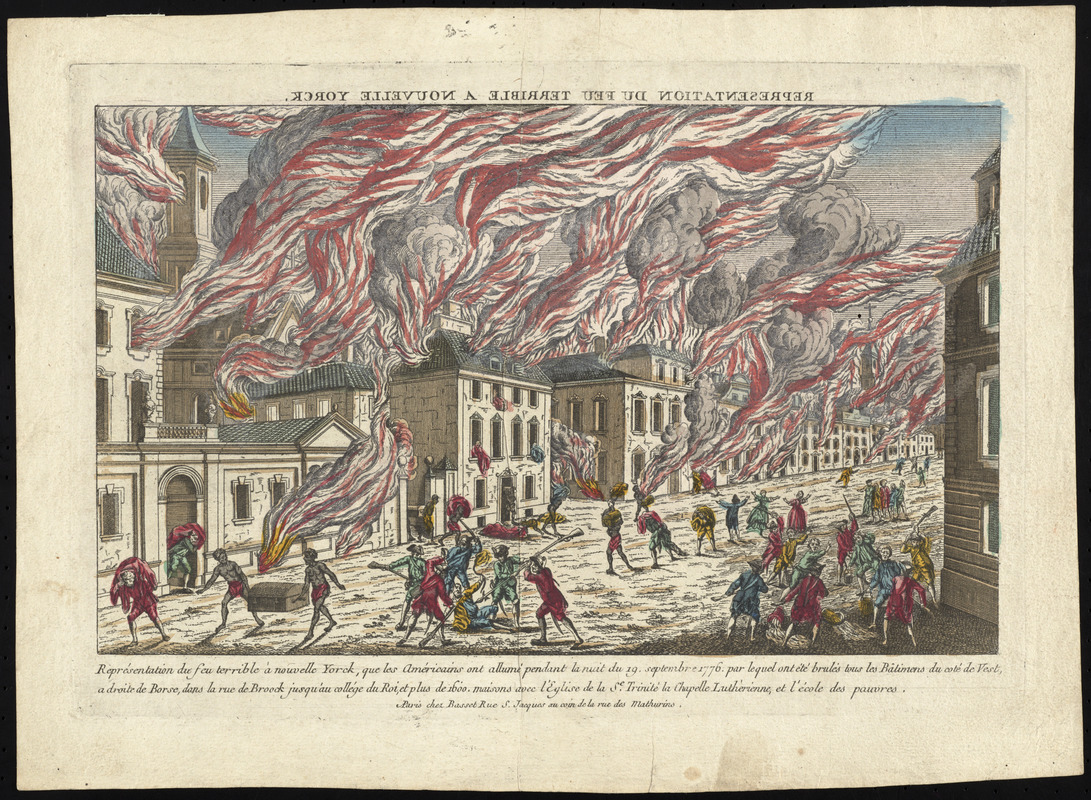

André Basset (fl. 1749-1785)

Représentation du feu terrible à Nouvelle Yorck

Paris, 1777. Optical view, etching, hand colored, 9.5 x 15 inches

Courtesy of Richard H. Brown

Attributed to Frenchman André Basset, this print provides a fictional representation of the Great Fire of New York. This fire occurred September 20-21, 1776, less than a week after the British entered the city. In the print, flames and smoke stream from a row of houses as chaos reigns in the streets. Armed soldiers beat civilians, while African slaves carry trunks of goods from looted houses. Consumers could purchase Bassett’s print and view it through a set of lenses to give the image dimension. With these lenses, the backwards title at the top of the scene would appear reversed.

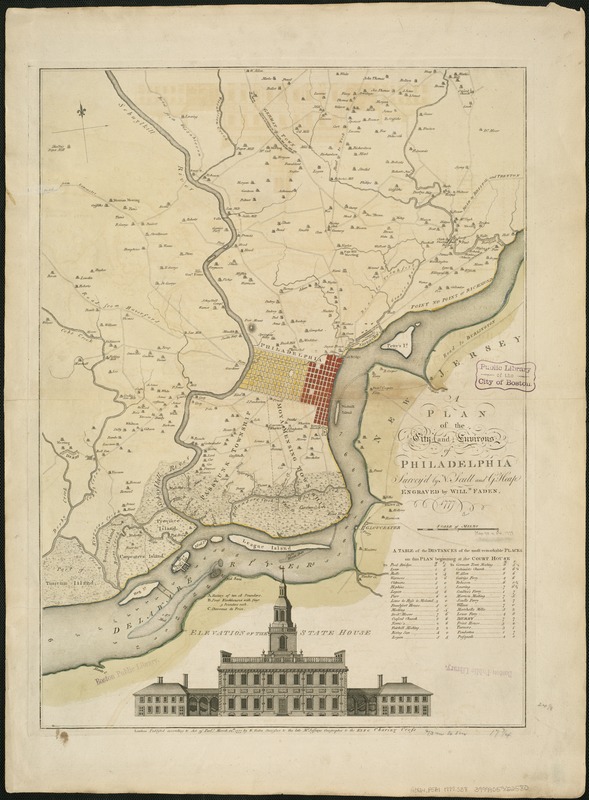

Nicholas Scull (ca. 1686–1781) and George Heap (fl. 1715–1760)

A Plan of the City and Environs of Philadelphia

Engraving, hand colored, 26 x 18 inches

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

William Faden, geographer to King George III, published this map of Philadelphia in March 1777. This map, or one of the earlier versions created by Nicholas Scull and George Heap, may have helped British troops when they occupied the city from September 1777 to June 1778. The map includes a city plan, labels the owners of properties in the surrounding area, and notes fortifications. Instead of a decorative cartouche, the map features an elevation of the Pennsylvania State House. Now known as Independence Hall, the building was famous even then as the site of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

This map can be viewed as a georeferenced overlay in an interactive application made especially for We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. View the application here.

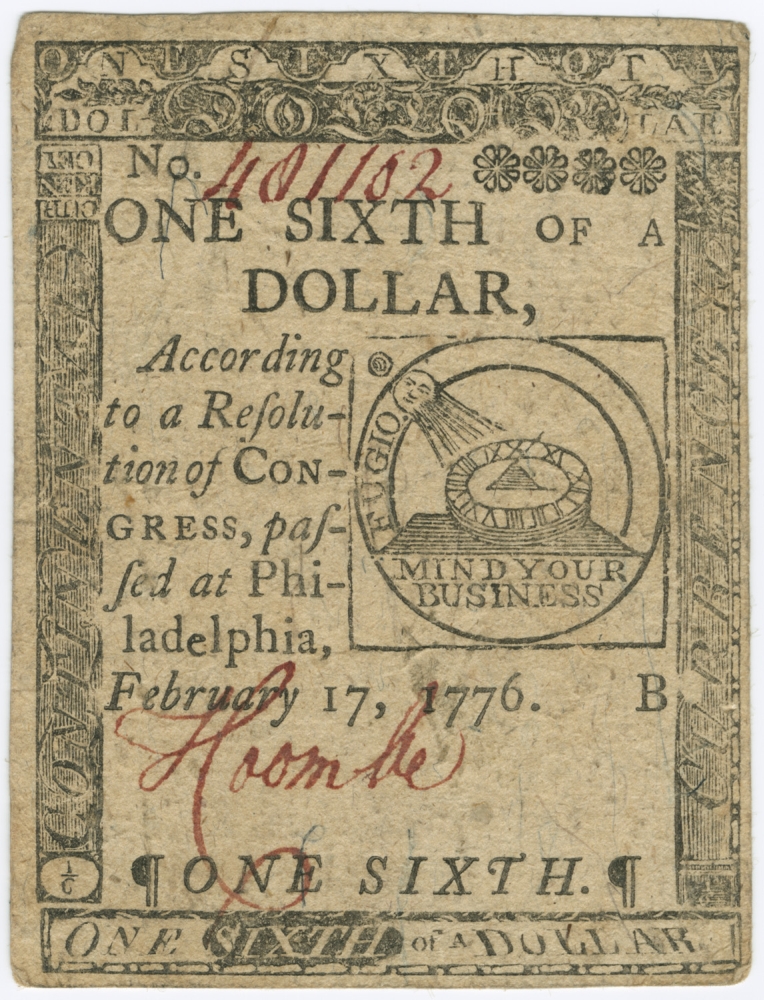

Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790)

One Sixth of a Dollar

Philadelphia, February 17, 1776. Paper currency, 3.25 x 2.5 inches

Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Print Department

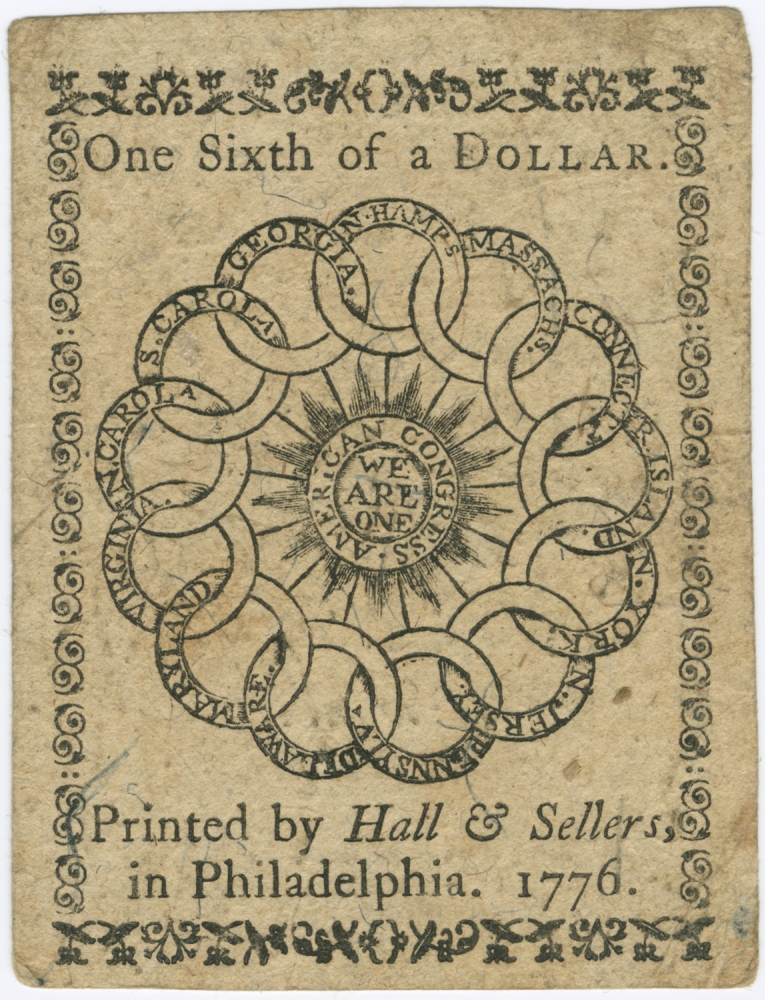

The Continental Congress first issued fractional currency in early 1776. Benjamin Franklin designed this note, which was worth one-sixth of a dollar. It offers the bearer some advice reminiscent of Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack. The front features a sundial with the words fugio (meaning “to flee” in Latin) and “Mind your business.” The phrases remind the possessor to proceed thoughtfully in financial matters because time passes quickly. The reverse side depicts thirteen interlocking rings, representing the original thirteen colonies. They encircle a blazing sun inscribed with the words “American Congress: We Are One.”

Elisha Gallaudet (ca. 1730-1805)

Continental Dollar “EG Fecit”

New York, 1776. Pewter coin, diameter, 1.4 inches

Courtesy of Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Gift of the Lasser Family

Like paper Continental currency, this dollar coin features designs by Benjamin Franklin. On one side, thirteen interlocking rings surround the phrase “We Are One.” Each ring is engraved with the name of a colony. The engraved words, “American Congress,” refer to the body that approved this coin in 1776. Currency varied among the colonies, so Congress decided to create a universal currency. The other side features a sundial to remind the viewer of passing time. It encourages Americans to “Mind Your Business,” or, in other words, to mind financial matters. The value of continental money suffered from depreciation during the war.

Michel Capitaine du Chesnoy (1746-1804)

Carte de l’affaire de Montmouth, ou le Général Washington commandon l’armée Américaine et le Général Clinton l’armée Angloise le 28 Juin 1778

1778. Manuscript, pen-and-ink and watercolor, 16 x 30.25 inches

Courtesy of Richard H. Brown

Michel Capitaine du Chesnoy, the Marquis de Lafayette’s map maker, drew this map following the Battle of Monmouth Court House in northeastern New Jersey. After confusion surrounding the Continental Army’s orders, the soldiers prevented the British troops from advancing. The battle occurred on a hot June day and hundreds of soldiers died of heatstroke. Women, who came to be referred to collectively as “Molly Pitcher,” supported the American troops by bringing water to cool the men and their guns. Although the battle ended inconclusively, it was a turning point for the professionalization of the American army as volunteer French and German military officers provided training.

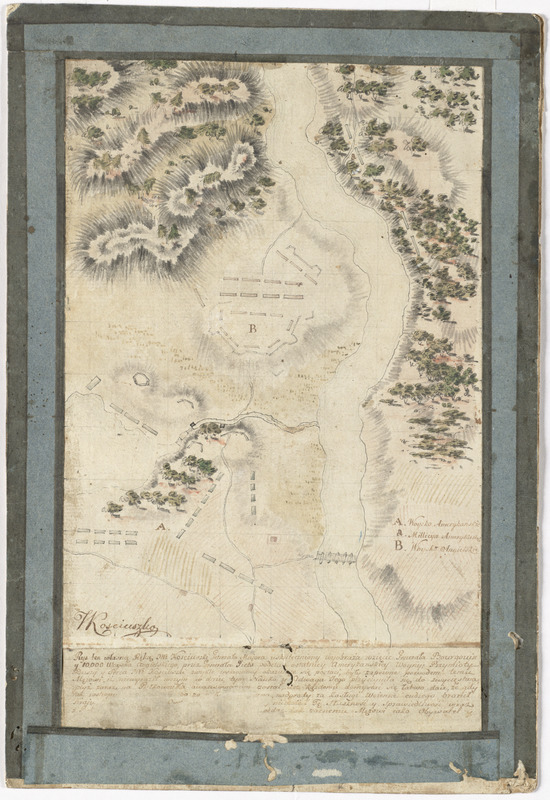

Tadeusz Kościuszko (1746-1817)