Introduction

The Civil War, from 1861 to 1865, is the centerpiece of our nation's story. It looms large, not merely because of its brutality and scope but because of its place in the course of American history. The seeds of war were planted long before 1861 and the conflict remains part of our national memory.

Geography has helped shape this narrative. The physical landscape influenced economic differences between the regions, the desire to expand into new territories, the execution of the conflict both in the field and on the home front, and the ways in which our recollections have been shaped.

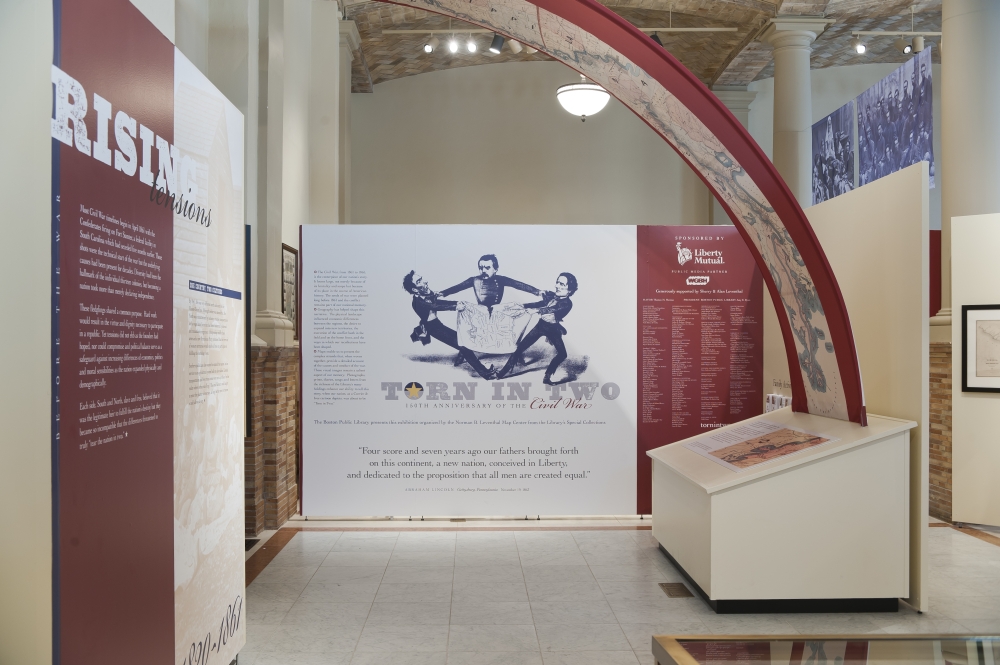

Maps enable us to present the complex strands that, when woven together, provide a detailed account of the causes and conduct of the war. These visual images remain a salient aspect of our memory. Photographs, prints, diaries, songs and letters enhance our ability to tell this story, when our nation, as a Currier & Ives cartoon depicts, was about to be "Torn in Two."

This exhibition tells the story of the American Civil War both nationally and locally in Boston, Massachusetts, through maps, documents, letters, and other primary sources.

1. Before the War: Rising Tensions

Most timelines of the Civil War begin in April 1861 with the firing on Fort Sumter, a federal facility in South Carolina which had seceded five months earlier. Those shots were the technical start of the war but the underlying causes had been present for decades. Diversity had been the hallmark of the disparate 13 colonies, but becoming a nation took more than merely declaring independence.

These fledglings shared a common purpose, to be different from Europe. Here hard work would result in the virtue and dignity necessary to participate in a republic. Yet the differences did not ebb as the founders had hoped, nor could compromise and political balance serve as a safeguard against increasing differences of economics, politics and moral sensibilities as the nation expanded physically and demographically.

Each side, South and North, slave and free, believed that it was the legitimate heir to fulfill the nation’s destiny but they became so incompatible that the differences threatened to truly “tear the nation in two”.

Hear Our Stories

Follow twelve individuals who come to life as they tell their experiences before, during and after the war. They are fictional characters but their stories and the history surrounding them is real. Which person interests you most? Which person is most like you? Whose side do you think you would be on?

Everybody next to me looks so calm. The crowd is cheering but a lot of people are crying, too. Most of those are mothers and sweethearts.

My name is Henry Bourne and I’m a new Infantryman in this war. We’re marching from town to the train station to take us South. I was really excited about going and I get excited again hearing the crowd. But I wish I had a sweetheart crying for me. All the girls will be taken by the time I get home, by those layabouts who stay behind or pay their way out. And I bet one of them will take my job at the bank.

We’ve arrived at the train. They tell us we’re going to Virginia. It sounds beautiful.

I do not know why God in His wisdom has chosen the lot of women to be so oppressed. Now that Father has died, my elder sister Lucy’s husband controls our fortunes. He is a man of no knowledge and even less intelligence and I fear that he will leave us in ruin. Mother is too stricken with grief to be of influence. What will befall us? There are no professions for us to enter. The few places for women tarnish our reputation so deeply as to be impossible. If we teach, we are considered ill-bred. Will I be reduced to that? Is my education to mean nothing? Our friend Louisa May Alcott makes money sometimes from her stories but I have not that talent.

I can’t stand this talk of war, but only because I am too old to volunteer. I will fight to the death to protect my land, where my family has lived for 75 years. It is the most beautiful piece of God’s earth in Louisiana. There is no need for war if the North would stop their hypocrisy, lies and judgment of a world they know nothing of. They accuse us of being slave-mongering demons, yet they trap factory workers in a life of debt that never ends. Their workers have no freedom, and my slaves are better treated than any factory girl of theirs. My workers are fed well and kept healthy, while theirs starve and freeze to an early death from their working conditions. And if we have not the right to govern ourselves, they want us to throw away the Constitution of these very United States. We have no reason to be united with them any longer and would be well rid of them.

We arrived today for the first days of training, all of us staunch soldiers ready to fight. Then we received our arms, and you never saw so many unhappy men anyplace but a funeral. They gave us flintlock muskets! We may as well be fighting the Mexican War, if it took place in 1800! When we saw that there were no bullets they gave us blocks of lead that we are supposed to melt down and make our own bullets from. No surprise that we lost our first battle at New Berne. Our next battle was even worse because we had new rifles, but we were cut off from the other regiments and most of us captured. I lay exhausted in the bushes and to my shame they sent out wagons to pick up soldiers like me.

I’ve just been bought as a gift for a lady. It makes me boil inside that I can be bought like a box of chocolates and sent away from my parents, but they are sending me tomorrow. I have already cried all the tears the world has. The lady is named Varina Davis. She is married to Jefferson Davis who has a plantation but is a Senator in Washington and used to be in the Army. He’s a lot older than she is. She’s different from most Southern ladies. She was a tom boy as a child. She is very educated and can express her opinions openly in any setting. I’ve never known a lady like that so at least I am curious.

Last night Pa left the dinner table early. Usually we all sit around and Pa talks about politics here in New York and across the country. Ma wants him to stop because she doesn’t want any of us children getting involved in any of the hot issues that are flying around us. She once threatened to stop making pie at all if it was going to encourage us all to stay at the table. I ran upstairs, saying I had studying, but really to watch where Pa went. I noticed he took a lantern with him into the barn and I saw little twinkles of light moving toward our barn. I couldn’t help it – I wriggled my way through the window in my room, climbed down the pear tree and ran to the loose board in the barn. I ran back soon because what I heard scared me so much. Pa was becoming a Copperhead. Some people call them “peace Democrats” because they are against the war that everyone says will happen soon. But lots of people call them traitors.

I call myself a governess, not a slave. The only person who can be a slave is one who lets their mind be enslaved. Joseph, a field hand, says it’s easy to say that when you’re an indoor slave. It’s true, my days are easier than Joseph’s. I teach ABCs and arithmetic to the little ones in the house ever since my master caught me reading. Before I was sold here, one of the boys in that house taught me to read. In the afternoon I get the older girls and the mistress ready for dinner, taking care of their hair and tightening their corsets. I caught 15-year-old Miranda trying to add rouge to her cheeks and I gave her a talking to. I take no mind to her pinching her cheeks to give her some color but any more than that will ruin her reputation.

I woke up, hearing loud banging noises. I was puzzled because it was still dark outside, like the middle of the night. I called out for Mother and the noises stopped. I tried to fall asleep again but I could barely breathe with fear. Finally, I just got up and decided I would boldly walk downstairs to find the noise. To my shock, it was Father, standing by the stairs surrounded by his tools. He told me sternly to go back to bed. Father so often encouraged me and so rarely corrected me that I could feel tears burning my cheeks. He came and put his arms around me. “Please go to sleep now, and I will explain this to you tomorrow.“

My name is Annie Sullivan and I’m one of the people they call a mill girl in Lowell, Massachusetts. I guess the girls here all used to be Yankee girls, but when the Famine happened my family and a lot of others came here looking for work so a lot of us are Irish now. It’s so different from places in Europe where mill girls are beaten and paid almost nothing. At least that’s what they say. It’s true we have to work 11 hours, but the old girls had to work 12. We make twice as much as we could as servants or seamstresses and I am putting a bit of savings aside from what I send home. My parents don’t know. I told them there was a rent increase for our boarding but there really wasn’t. God forgive me! Anyway, now they say war is coming and I’m very scared.

Our leadership has lost its head by starting this war. They forget those of us who have no reason to go to war. I have never used slave labor on my farm in Georgia, nor do I live in a mansion of stately grandeur. I have ten children, all of whom work on the farm, and if they are not enough I hire the help I need. I am no Republican and I have little respect for Mr. Lincoln, but at least there is sense in that odd head of his. Imagine that Mr. Davis thinks my sons and I should go to war for the plantation owners. Everybody says this war is about the right of a state to govern itself, but then why does everyone talk about the impossibility of running plantations without slaves?

Can no one see the damnation of God’s fury that will descend upon us all? By all that is Holy, no man shall own another. How can he if he is to obey God’s law to love our neighbors and treat them as we would be treated? This is not only a Christian tenet, but one we share with our Jewish brethren. Preacher told us that a famous rabbi named Hillel called for the same law at the time Jesus lived. And as they both called that we shall love our God with all our soul and heart and mind, as in Deuteronomy 11:13-21, how can we not obey? Do we not know that should God send the angels of darkness upon us we shall all perish as one, not separated into sinner and believer? Father says it is time for me to quit the seminary and find honest labor. But I believe God calls me to fight this fight against evil in His name.

It seems all we talk about in Framingham, Massachusetts is war. I own a printing shop and every morning the men of my neighborhood gather and talk about their plans to volunteer. For them, as white men, this is courageous talk. For me, as a black man, it is nothing but pain. People say that we will never be allowed to fight, because they don’t want to give us guns and because they believe we are all cowards who will run. Every black man wants to enlist, because we are patriotic Americans and because we want the chance to show our true character. We have a stronger reason to fight than any white man. But even Mr. Lincoln says no, because the border states will turn against the Union if they arm us.

1A. One Country, Two Cultures

By 1861, life was very different north and south of the Mason Dixon line. Although neither was monolithic, industry, reliable transportation and a wage labor force prevailed in the North. Agriculture dominated the South where limited transportation and few urban areas were not a problem for the realm where cotton was ‘king’. Moral superiority and political expediency were heaped on these economic differences, each side drawing on those aspects of the American ideal that most suited its needs.

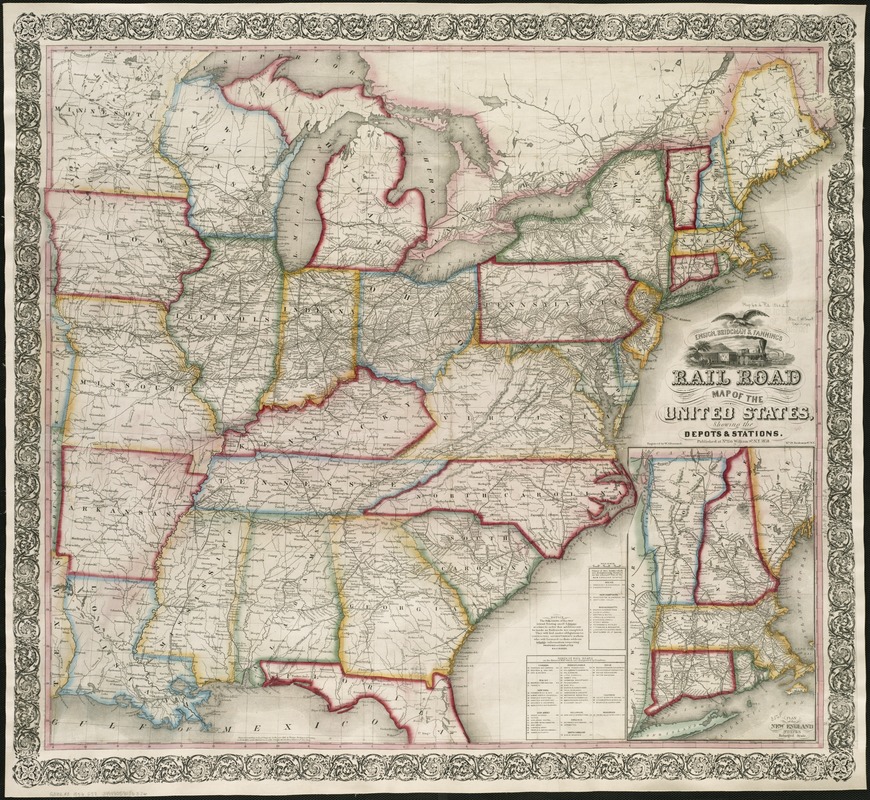

Ensign, Bridgman & Fanning’s Rail Road Map of the United State showing the Depots and Stations

New York, 1859.

At first glance, this vibrant map depicts a prosperous and unified country, accentuated by a cartouche adorned with an eagle symbolizing national unity. A vignette displays a train and steamboat departing the countryside for the city, suggesting a natural progression of economic development.

However, closer examination reveals major regional differences. The North appears as a dense pattern of geographic information, dotted with cities and towns connected by a complex railroad network. By contrast, the rural southern states reflect much less urban development and railroad mileage.

These opposing settlement patterns reflected differing ways of life that underlay the frictions threatening to tear the country apart. Two regions that did not share a common economy, culture, or philosophy concerning slavery constituted this divided “nation.“

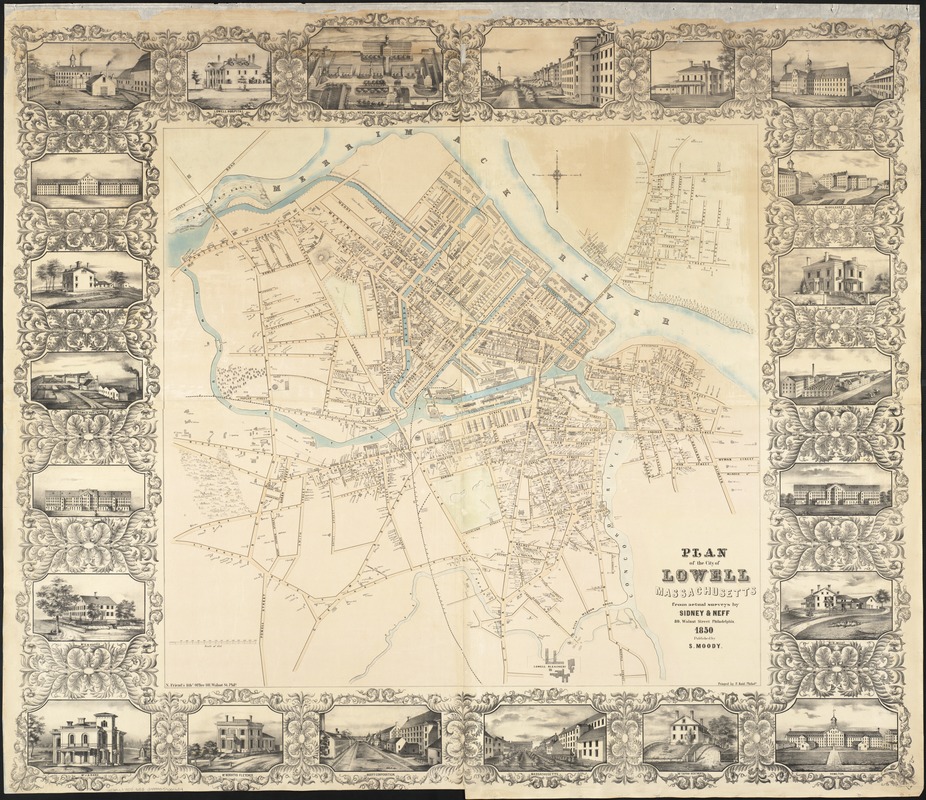

Sidney and Neff

Plan of the City of Lowell, Massachusetts

Philadelphia, 1850.

The communities that dotted the northeastern landscape reflected an economy that was heavily industrial and urban. The Industrial Revolution, which greatly accelerated urban growth, was introduced into southern New England at the beginning of the 19th century, with factories utilizing abundant local waterpower resources.

Lowell, Massachusetts, was the epitome of a factory town. In 25 years the city grew exponentially, and by 1850 had a population of 30,000, making it the nation’s largest industrial community. Thirteen textile mills, depicted in the marginal illustrations, provided the focus of this industrial activity.

Paradoxically, the raw material supplying Lowell’s factories, creating its wealth, was cotton from the American South. The factories first employed local single women, but eventually they were replaced by Irish immigrants in the 1830s and 1840s.

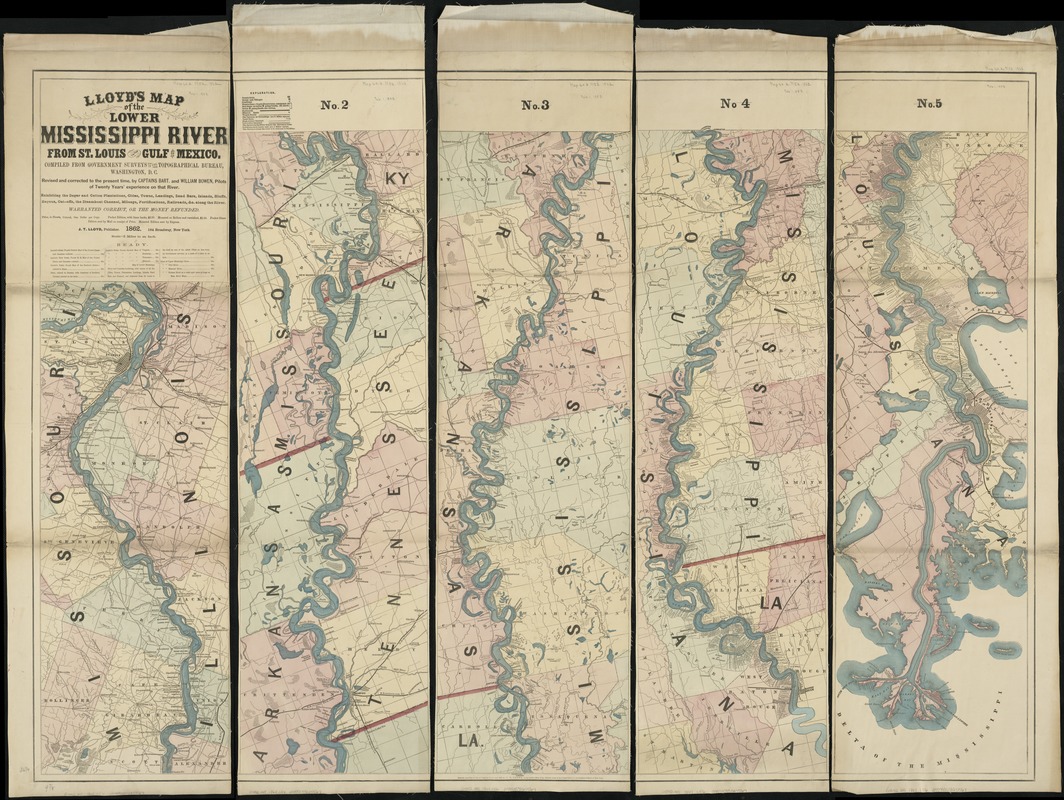

James T. Lloyd

Lloyd’s Map of the Lower Mississippi River from St. Louis to the Gulf of Mexico . . . exhibiting the sugar and cotton plantations, cities, towns, landings, . . .

New York, 1862.

Southern settlement patterns were primarily rural and agricultural. Although some railroads existed by the 1850s, mileage and connectivity were limited. There was heavy reliance on river transportation as suggested by this multi-sheet map of the Mississippi River.

Cutting through the heart of the country, the Mississippi created alluvial soils ideal for commercial agriculture. Near New Orleans sugar was the primary crop, while upriver in northern Louisiana and in Mississippi, Arkansas, and Tennessee, cotton was the major cash crop.

While individual plantations are not associated with either crop, plantation and landowner names identify the large landholdings lining the river’s edge. One of particular note is Jefferson Davis’ plantation, which is labeled as Davis Bend or Hurricane Plantation, located 20 miles downstream from Vicksburg on a large meander of the river.

Andrew J. Powell and Robert H. Bradford

Detail from Map of the Parishes of Pointe Coupee, West Baton Rouge and Iberville including parts of the parishes of St. Martins and Ascension, Louisiana . . .

New York, 1859.

Reproduction courtesy Lawrence Caldwell.

Louisiana’s sugar and cotton plantations are shown in Louisiana’s sugar and cotton plantations are shown in great detail on this landownership map of Baton Rouge and surrounding parishes. The long linear properties, reflecting the original French and Spanish settlement of the area, line the meanders of the Mississippi River.

By 1860, Louisiana had roughly 1,300 sugar plantations, with the properties delineated on this map accounting for nearly 25 % of the state’s sugar production. Because of superior agricultural and manufacturing capabilities, Louisiana had an edge over Caribbean competitors and controlled nearly 60% of the U. S. market.

Sugar production, like textile manufacturing, required large amounts of capital investment. Louisiana was at the northern edge of sugar-growing latitudes, and variable weather affected yearly production. As a result, many partnerships were established to spread risk, as suggested by multiple landowners’ names on the map.

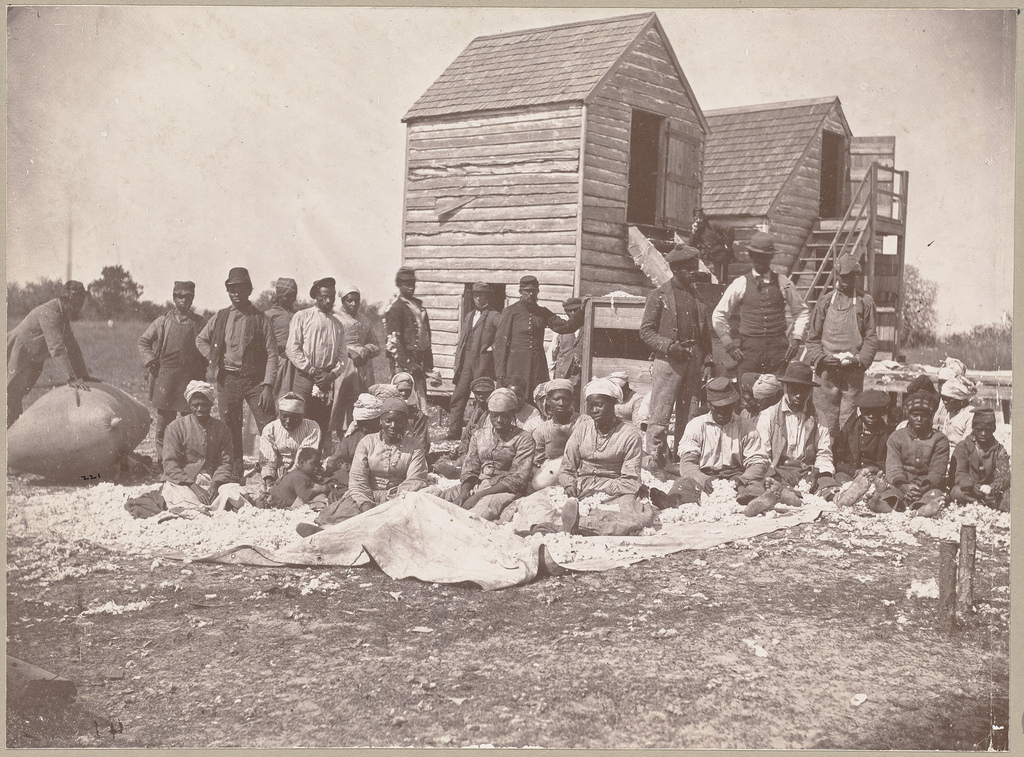

Henry P. Moore

Hilton Head, Drayton’s Plantation, Sorting Cotton

1862.

Rare Book Dept.

A rare example documenting mid-19th century slave life, this photograph was taken by New Hampshire photographer Henry Moore while recording the activities of Union regiments following their occupation of Port Royal, November 7, 1861. During Union control, southern landowners abandoned their plantations, leaving the slaves under the care of northern troops and newly organized freedman’s societies.

Moore most likely arranged the subjects in this composition which he took at a Hilton Head plantation owned by Thomas F. Drayton, where 52 slaves were employed primarily in cotton production. In an ironic twist, Drayton directed the Confederate troops at the battle of Port Royal, while his younger brother Percival commanded a ship in the Union navy supporting the attack on Port Royal.

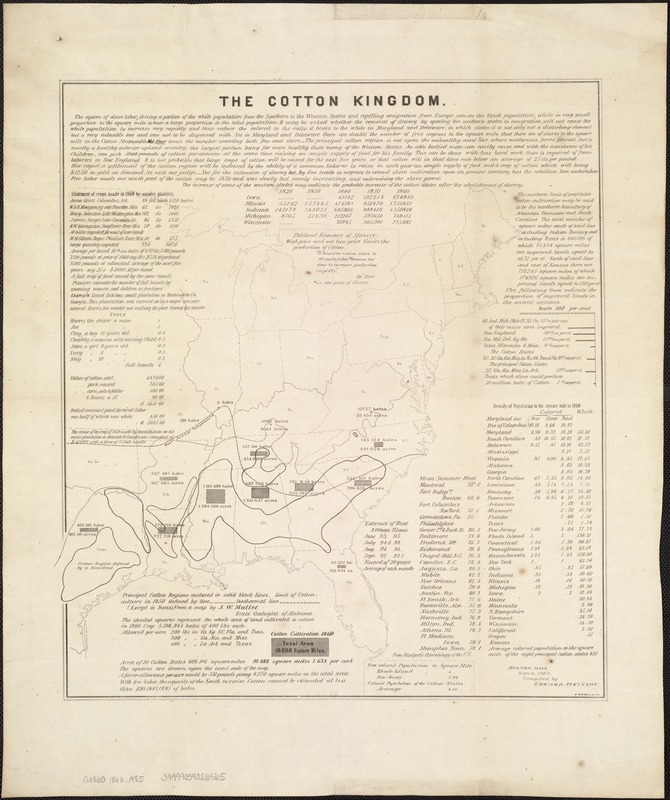

Edward Atkinson

The Cotton Kingdom

Boston, 1863.

During the antebellum period, cotton was considered “king“ in the South, as it was the region’s predominant cash crop. Cotton cultivation began in coastal South Carolina, but with the invention of the cotton gin in 1793, spread rapidly as far west as Texas.

Requiring fertile soil and an extensive growing season, there was a northern geographic limit to cotton cultivation. This boundary is suggested by the “mean summer temperature“ line on this detailed statistical map delineating the major areas of cotton production.

Published by Brookline resident Edward Atkinson, this map was one of many documents about cotton that he authored. An executive officer for a number of Boston area textile factories, Atkinson was also an ardent abolitionist and wrote numerous tracts advocating cotton cultivation with free labor.

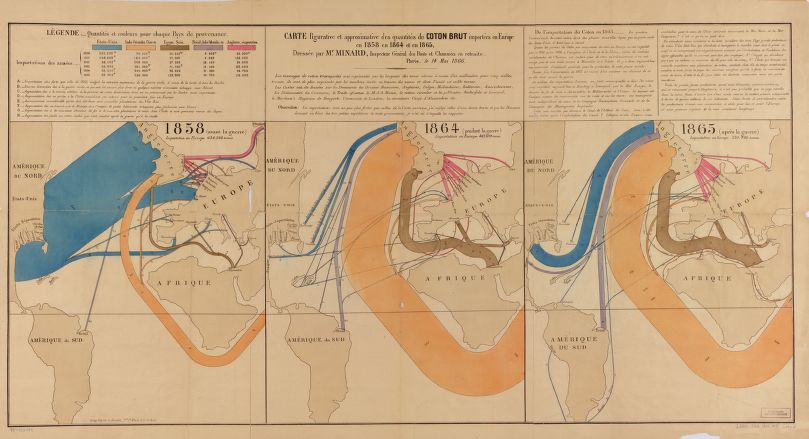

Charles Joseph Minard

Carte figurative et approximative des quantités de coton brut importées en Europe en 1858, en 1864 et en 1865

Paris, 1866.

Reproduction courtesy Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Besides supplying raw cotton to northern textile mills, the South also developed an extensive trade with Europe. This innovative graphic created by French engineer Charles Minard provides a global perspective of the mid-19th century cotton trade.

Specifically, it demonstrates the dramatic changes that occurred in the quantities of cotton imported into Europe before, during, and after the war. According to Minard's research, the South accounted for 84% of this volume before the war, but with the North's blockade of the southern coast that share dropped to less than 10% during the war.

While Confederate politicians hoped to leverage the European dependence on southern cotton into international recognition and military aid, European industrialists turned to Egypt and the East Indies for their supplies.

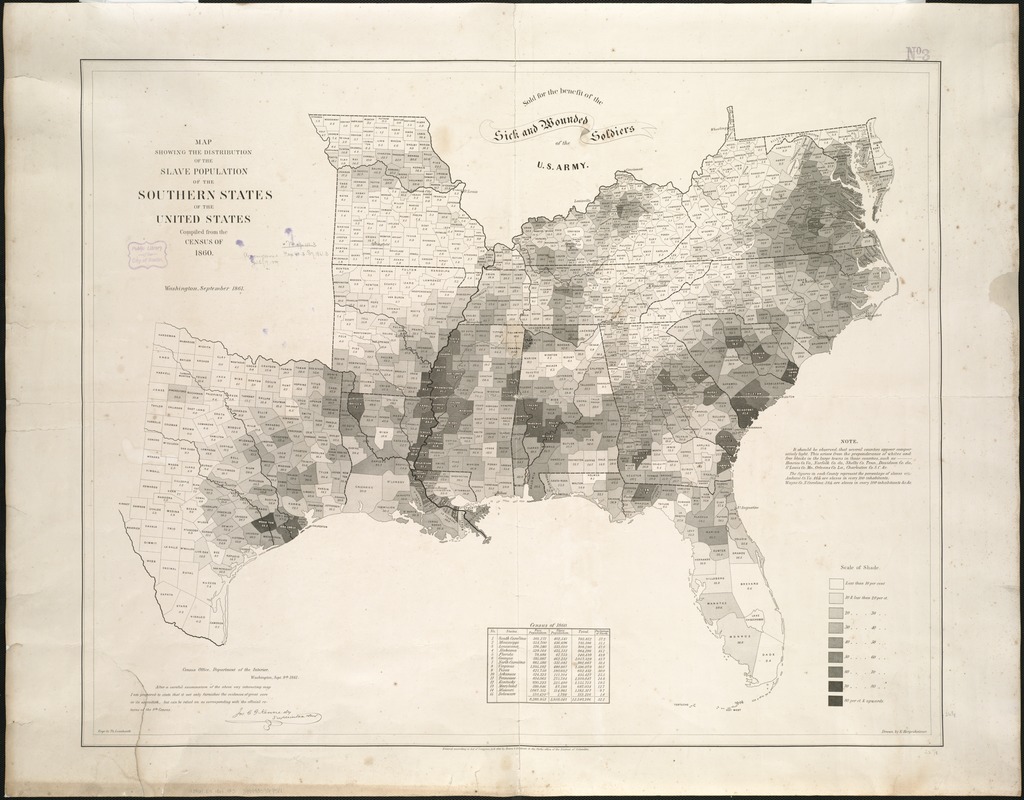

Edwin Hergesheimer

Map Showing the Distribution of the Slave Population of the Southern States of the United States Compiled from the Census of 1860

Washington: Henry S. Graham, 1861.

Based on 1860 census data, this map plots the percentage of slaves by county for the southern states. It was one the first statistical or thematic maps published in the United States.

It is readily apparent that there were several major concentrations of slavery throughout the region, particularly where commercial plantation agriculture was most profitable – tobacco, sugar and cotton being the cash crops. Attesting to this map’s importance to Abraham Lincoln, it was deliberately depicted in Francis Bicknell Carpenter’s oil painting, First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation of President Lincoln. The artist’s memoir records Lincoln’s fascination with the map, not just for its symbolic power, but because it allowed him to follow and plan military movements, and to relate those actions to his emancipation policies.

1B. Anti-Slavery Movement

Southerners defended slavery, yet there was increasing opposition. Some decried its economic inefficiency. Others saw it an impediment to the growing republic. Slaves could go back to Africa but not into the new territories of the United States. At the core were those who objected on moral and humanitarian grounds. They called for the complete abolition of slavery throughout the union and its territories. They provided aid for those who bravely ran away, providing guidance, resources, and safe harbor along the Underground Railroad.

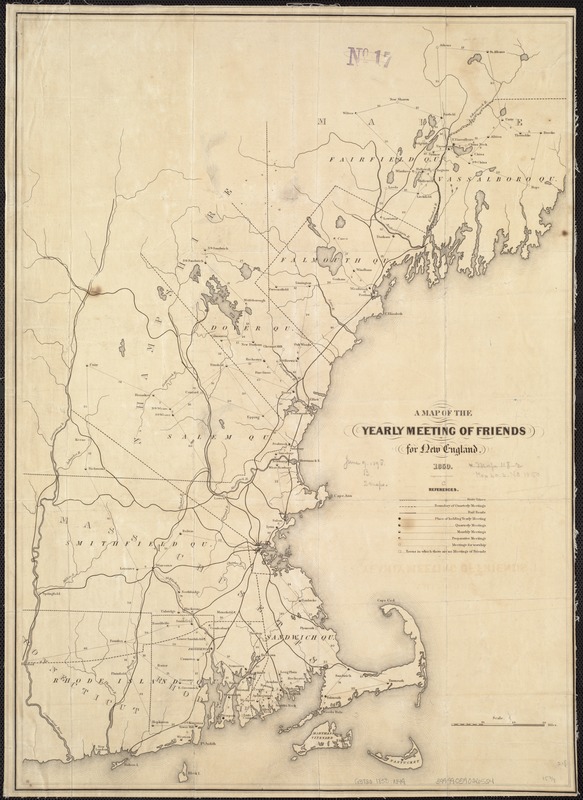

A Map of the Yearly Meeting of Friends for New England

1850.

The anti-slavery movement had a long history and many voices. One of the earliest and most vocal was from the Quakers, first in Pennsylvania but also in New England and the Ohio River Valley.

Although various New England denominations and societies were involved in the anti-slavery movement, this map showing Quaker meeting houses in New England not only underscores their rhetoric against slavery but also their involvement in assisting slaves to escape their bondage. By comparing this map with maps of the Underground Railroad, it is possible to see a strong correlation between the meeting houses and communities involved with the railroad.

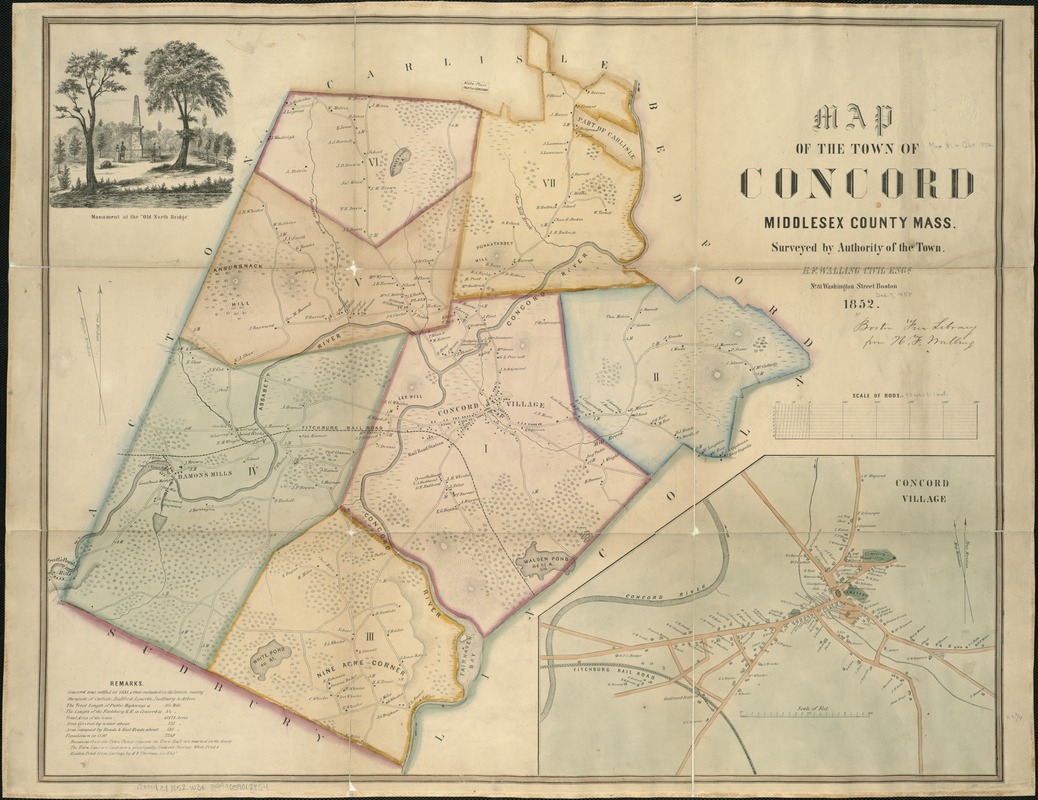

Concord, Massachusetts, which is widely recognized for its role in the American Revolution and the literary and philosophical “revolution“ of Transcendentalism, was also a center of anti-slavery activity. Among those residents who supported the anti-slavery cause were Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry David Thoreau.

This 1852 landownership map of Concord portrays the community a decade before the Civil War. The site of the first battle of the American Revolution is marked with a monument labeled “Birthplace of American Liberty.“

It is also possible to locate the homes of a number of those involved in the anti-slavery movement. Emerson's and Hawthorne's homes are near the village center. Others include Mary Rice, a station master on the Underground Railroad, and Peter Hutchinson, a free black man.

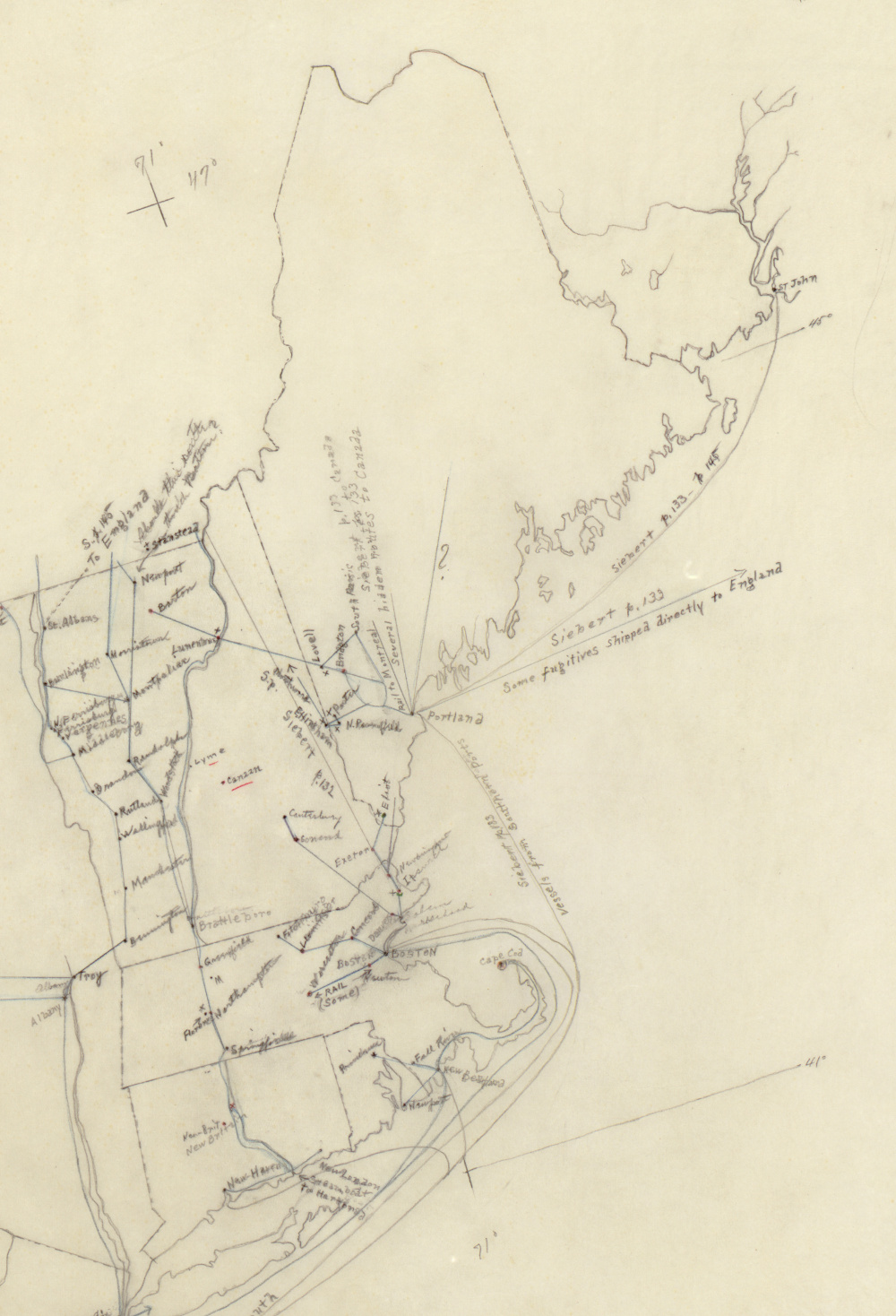

Federal Writers Project

[Underground railroad map of the United States, ca. 1838-1860]

1941?

Reproduction courtesy Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Because the Underground Railroad was based on the combined efforts of many sympathetic people working secretly to assist slaves in moving toward freedom, there were no contemporary maps to guide those who escaped or that depict the full extent of this complex communication network. However, historians have been able to document “stations“ or places that assisted runaway slaves and the major routes that they traveled, based on oral histories gathered from slaves who reached freedom.

One of the primary efforts to “map“ the Underground Railroad is a manuscript map based on slave narratives collected and recorded by the Federal Writers Project during the 1930s. Displayed here is a detail from that map illustrating the New England area.

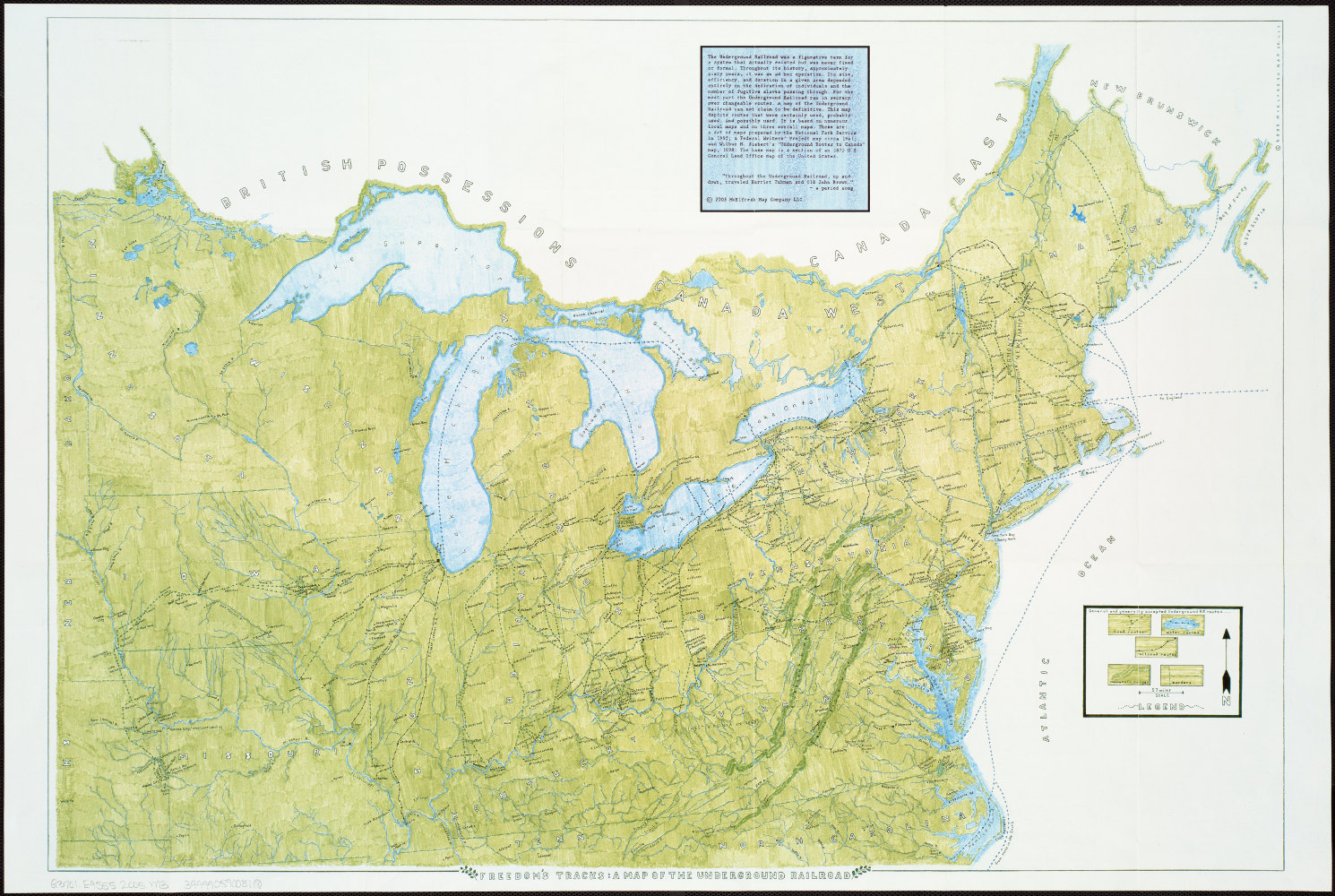

Earl McElfresh

Freedom’s Tracks: A Map of the Underground Railroad

Olean, NY: McElfresh Map Company, 2005.

Reproduction courtesy McElfresh Map Company.

This modern reconstruction presents a comprehensive depiction of documented routes, stations, and destinations on the Underground Railroad. It is apparent that there were many journeys generally in a south to north direction, both by land and sea. Although the routes traversed all the states north of the Ohio River and the Mason-Dixon Line, there was a heavy concentration in the Mid-Atlantic and New England states.

By closely examining both of these maps, it is evident that there were a number of “stations“ in the Boston area, including such recorded stations as the William Jackson House in Newton, the William Lloyd Garrison House in Roxbury, the William Ingersoll Bowditch House in Brookline, and the Lewis and Harriet Hayden House on Boston's Beacon Hill.

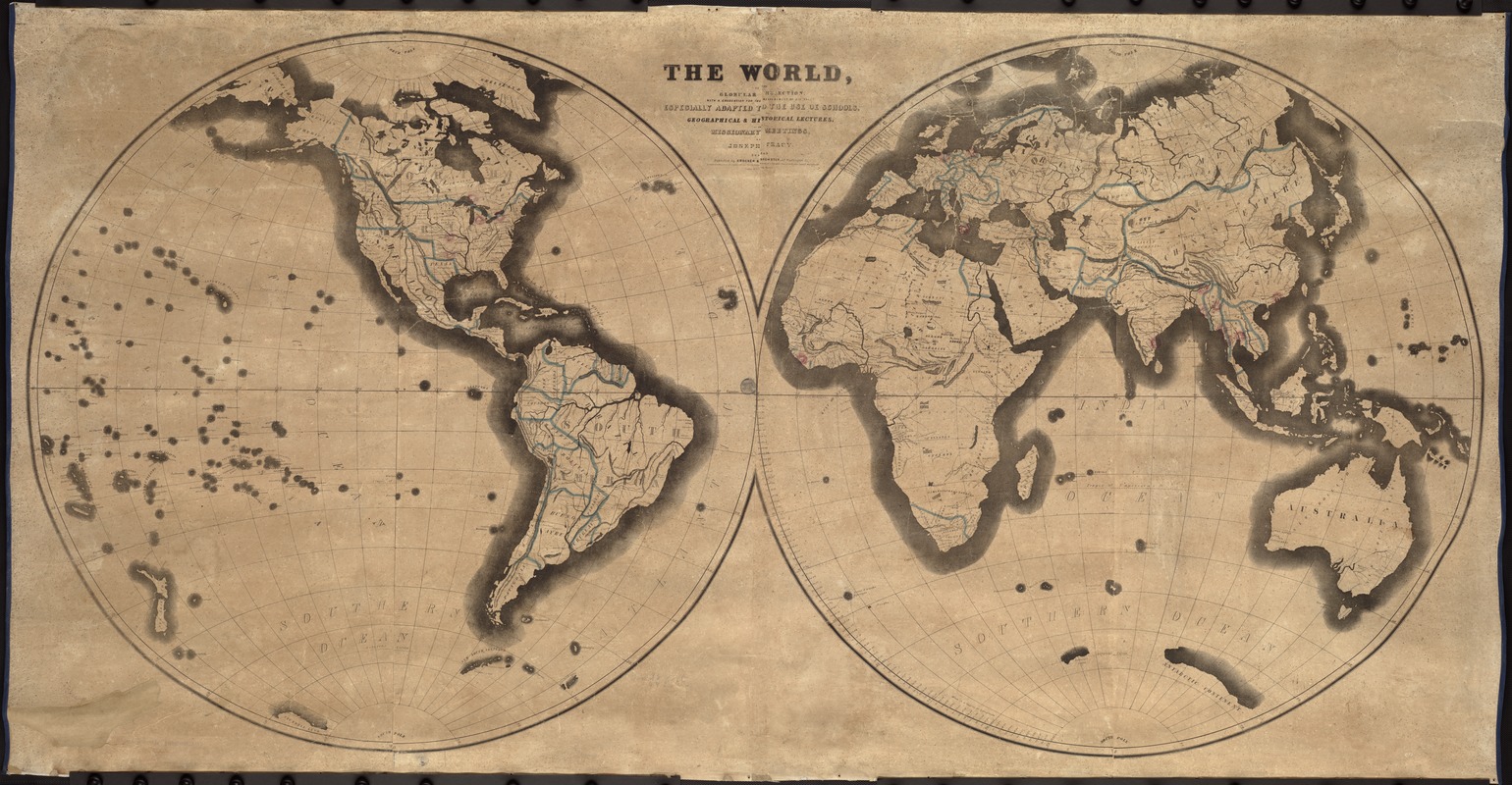

Joseph Tracy

The World on the Globular Projection with a graduation for the measurement of distances, especially adapted to the use of schools, geographical & historical lectures, and missionary meetings

Boston, 1843.

This world map, published primarily for educational purposes, locates missionary activity in the United States and around the world. It also provides a global perspective for understanding the origins of the African slave trade, which had been banned in the United States since 1808, and the rising momentum of the anti-slavery cause.

The map was prepared by Joseph Tracy who served as the secretary of the Massachusetts Colonization Society, an affiliate of the American Colonization Society. Reflecting his corresponding interest in foreign missions, he located an American mission in Liberia.

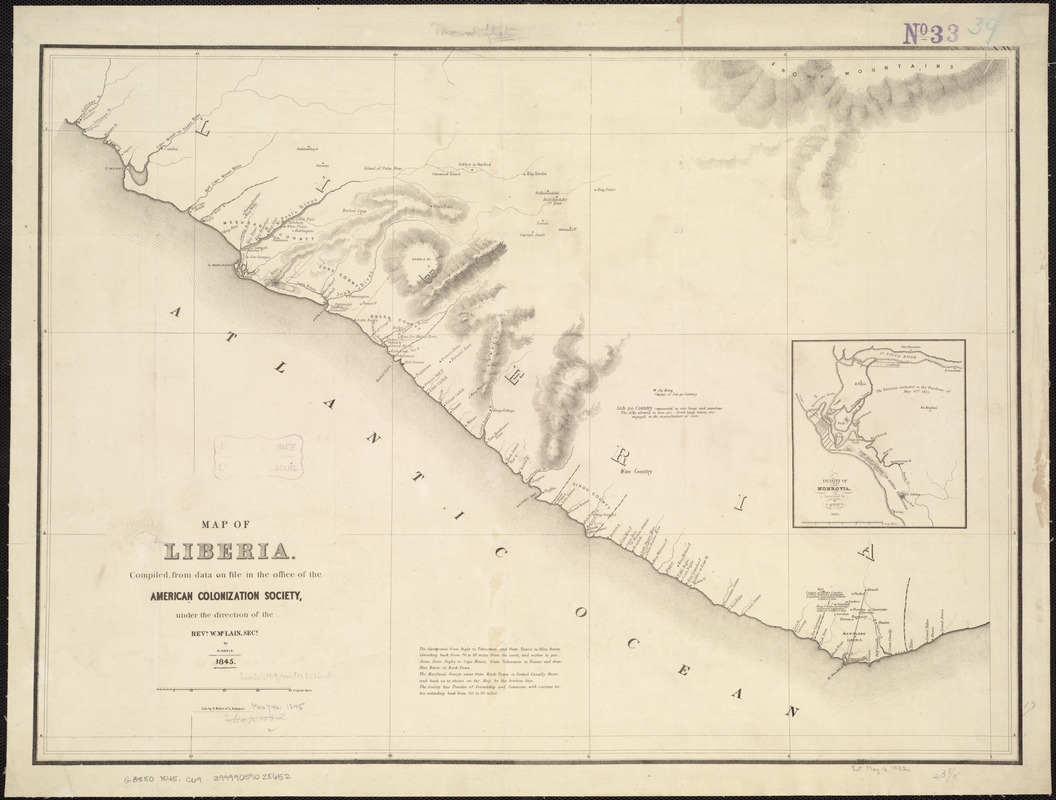

W. McLain

Map of Liberia, compiled from data on file in the Office of the American Colonization Society

Baltimore, 1845.

Besides escaping to the North, another alternative for freed slaves was “colonization“ or resettlement in Africa. Several organizations were founded to encourage and assist with this relocation, but this was not a universally appealing choice.

The American Colonization Society, organized in 1816 in Washington, DC, assisted thousands of emancipated slaves in returning to Africa. The Society established the colony of Liberia, named from the Latin word for “free,“ on the west coast of Africa as a homeland for former slaves from the United States.

An 1845 map of Liberia published by the Society shows that many place names were of African origin. However, several reflect a strong American influence, as does Monrovia, named for President James Monroe.

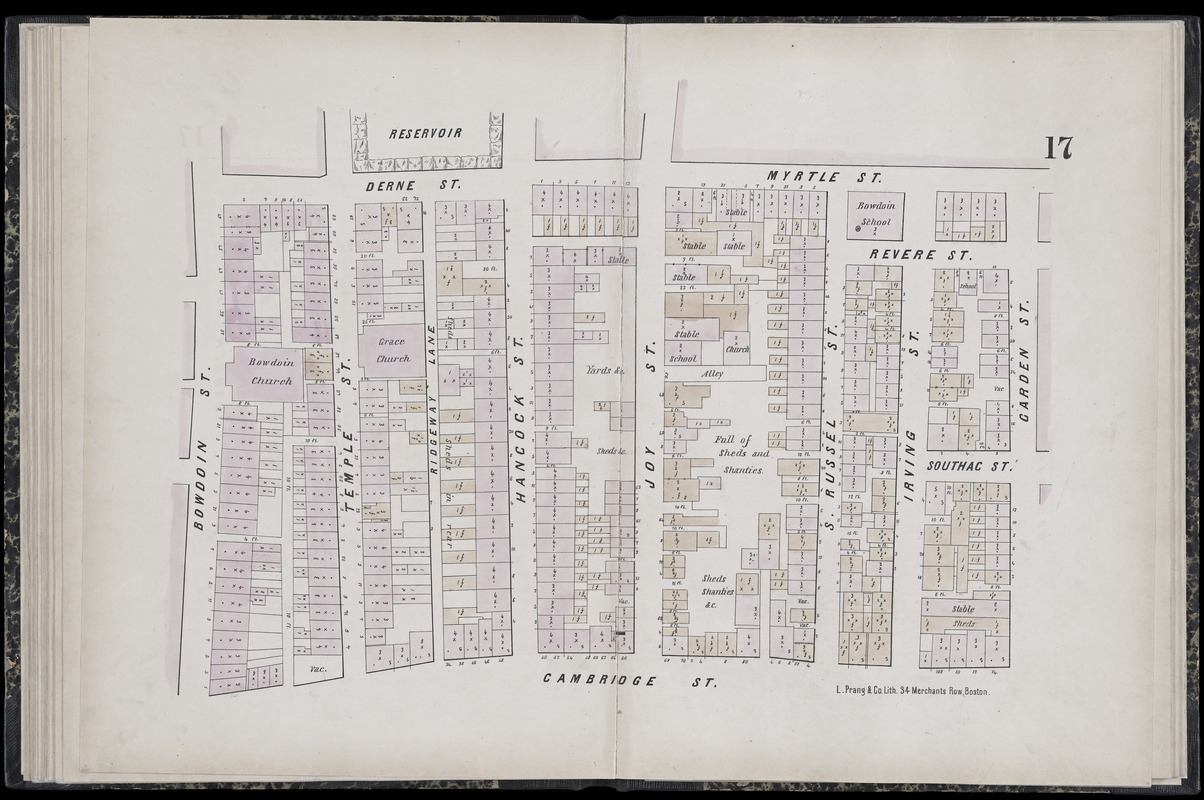

C. Pinney

“Sheet 17” in Plan of the City of Boston

Boston, 1861.

During the antebellum period, Boston had a thriving free African American community. By 1860, more than half the city’s black population of 2,000 lived on the north slope of Beacon Hill adjacent to the Massachusetts State House. This neighborhood became a center for Boston’s abolitionist movement and many fugitive slaves escaping via the Underground Railroad found refuge here.

A portion of this neighborhood is depicted on a sheet from an 1861 fire-insurance atlas. Of particular interest are the church and school on the alley (today’s Smith Court) off Joy Street, marking the location of the African Meeting House, the oldest extant black church building in the United States, and the Abiel Smith School, the only black public school in Boston until 1855, when schools were integrated.

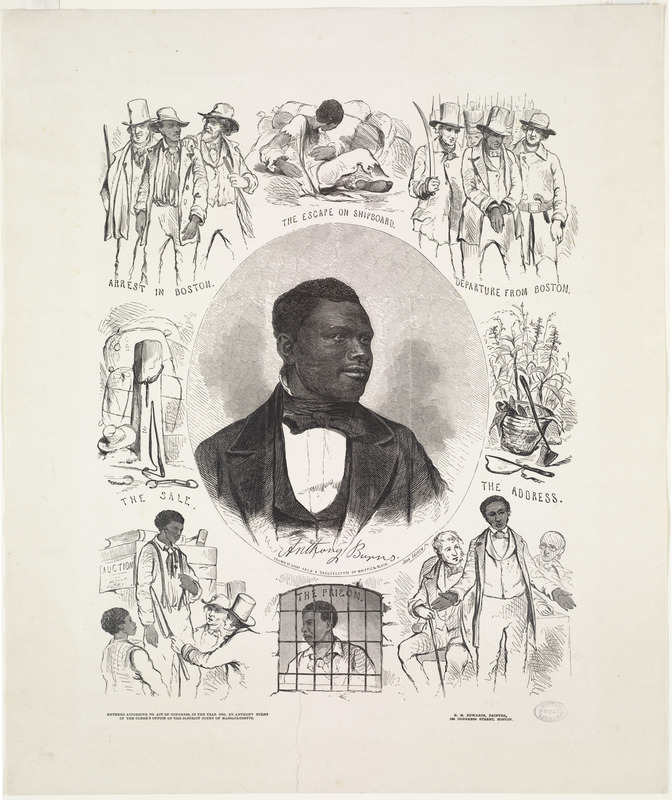

John Andrews

Anthony Burns

Boston, 1855.

Print Dept.

Of the many fugitive slaves coming to Boston, one who received considerable publicity was Anthony Burns. Escaping slavery in Virginia, he ran away to Boston. In 1854, he was arrested and tried, under provisions of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. Following a protest rally at Faneuil Hall and attempts to “rescue“ him, President Franklin Pierce sent Federal marshals to ensure order and a military escort for Burns’ return to Virginia. Eventually, Boston sympathizers purchased his freedom.

The case stirred passions among those who had been indifferent. While the ultimate statement of slaves as property would come with the 1857 Dred Scott decision, the Burns case was one more step on the road to disunion.

1C. Sectionalism and Westward Expansion

While the war would pit North against South, it was the West that became untenable. Physical expansion marked the country’s first decades and the extension to the Pacific by mid-19th century represented more than just economic gain. It was the nation’s Manifest Destiny to spread, but which vision would hold in these new territories? Before they took to arms, Americans battled in the courts, state houses, Congress, and individual states. The election of Lincoln in 1860 led the Southern states to believe that secession was their only option.

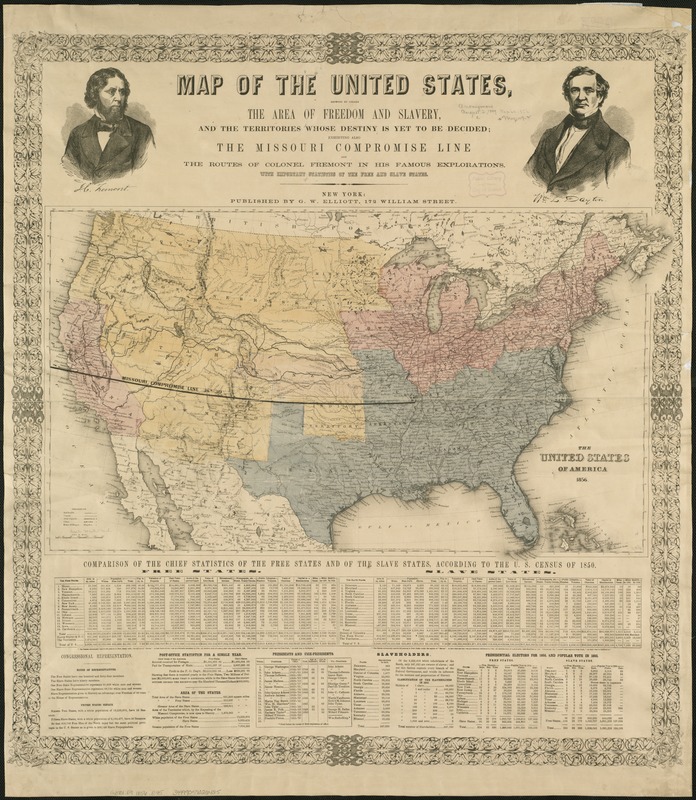

Map of the United States, showing by colors, the Area of Freedom and Slavery, and the Territories whose destiny is yet to be decided, exhibiting also the Missouri Compromise Line and the routes of Colonel Fremont in his Famous Explorations with important statistics of the Free and Slave States

New York: G.W. Elliott, 1856.

Published as a campaign poster supporting the Republican Party's first presidential bid in 1856, this broadside provides a commentary on the geographical sectionalism that was polarizing the nation. Using 1850 census data, it tabulated the demographic and economic differences between free and slave states, highlighting political concerns that the balance of Congressional power would shift as newly acquired western territories were admitted as states into the Union. The map clearly marked the 1820 Missouri Compromise line, which had defined the boundary between free and slave states. However, the passage of the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act nullified this long-standing compromise line, and potentially opened the entire western territory to slavery because it sanctioned “popular sovereignty“ whereby citizens of each territory could vote on the slavery issue.

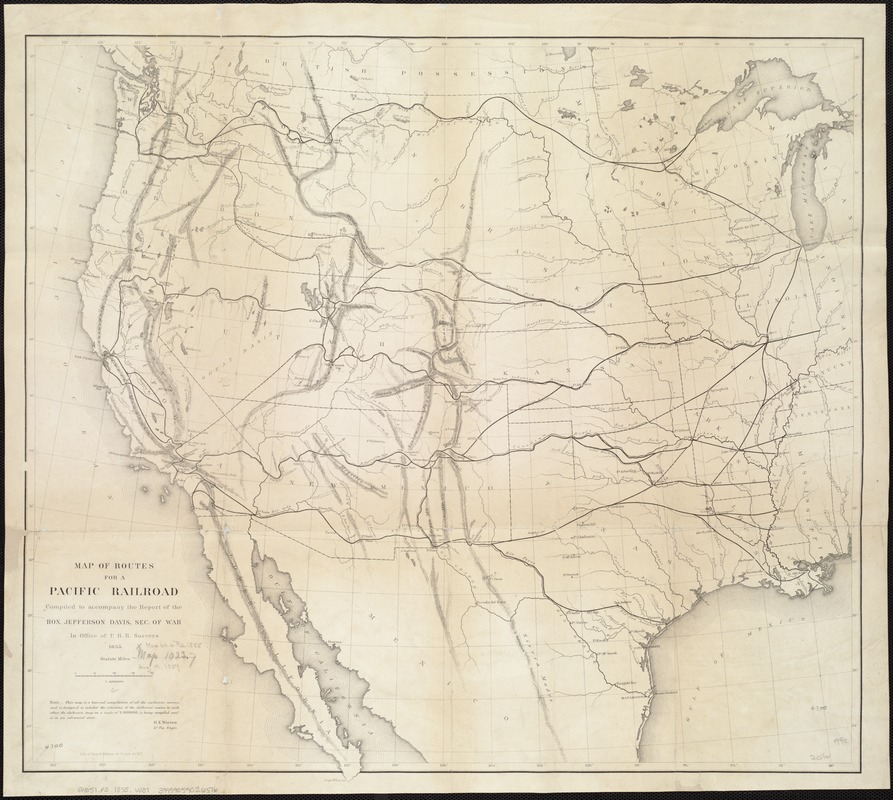

G.K. Warren

Map of Routes for a Pacific Railroad compiled to accompany the Report of the Hon. Jefferson Davis, Sec. of War

Washington, DC, 1855.

Sectional interest in controlling the West was particularly evident in the Pacific Railroad Surveys, conducted from 1853-54 under the direction of then Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis. Four east-west traverses, designed to satisfy both northern and southern sectional interests, were surveyed in order to determine the most practical route for the first trans-continental railroad. The potential routes were delineated on a “hurried“ map prepared by Lt. G.K. Warren in 1855, shortly after the surveys were completed. Although none of the four routes was selected in its entirety, the first trans-continental railroad followed a mid-continental route connecting Omaha and San Francisco. Begun during the war, this rail line was not completed until 1869, four years after the war ended.

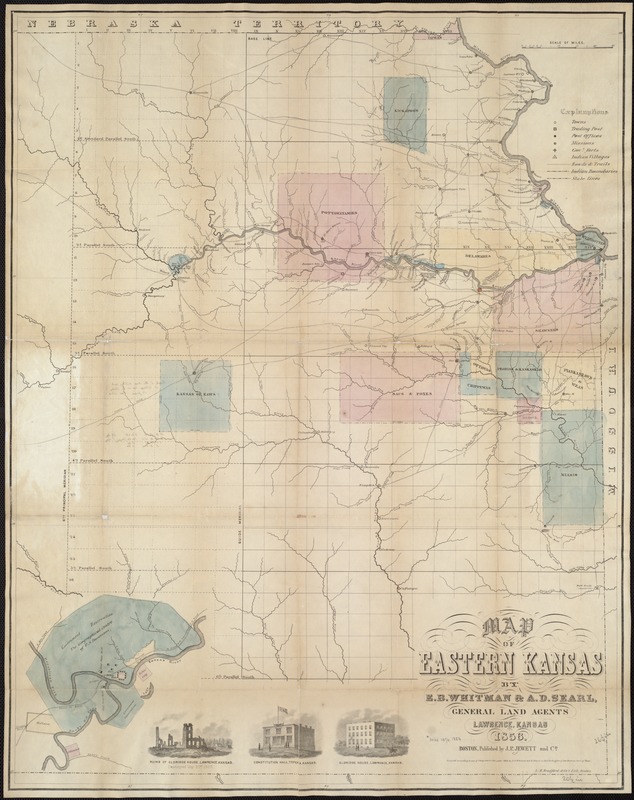

E.B. Whitman and A.D. Searl

Map of Eastern Kansas

Boston: J.P. Jewett, 1856.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 established two new territories with a provision that settlers would decide whether they entered the Union as free or slave states. This legislation negated the 1820 Missouri Compromise which previously designated Missouri’s southern boundary as the dividing line between free and slave states. As eastern Kansas was settled during the 1850s, intense competition and armed conflict developed between pro-slavery and anti-slavery (Free State) factions, and the territory came to be known as “Bloody Kansas.“ Pro-slavery settlers moved from neighboring Missouri which permitted slavery, while groups such as the New England Emigrant Aid Company promoted anti-slavery settlement.

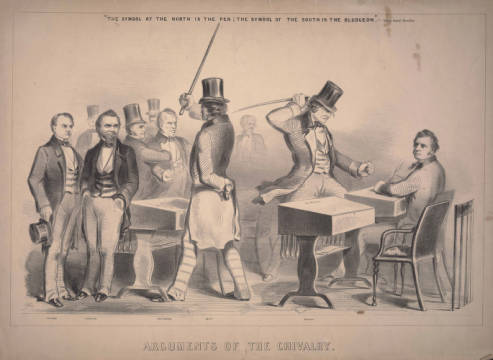

Winslow Homer

Arguments of the Chivalry

[Boston: J.H. Bufford, 1856].

Courtesy of the Boston Athenaeum.

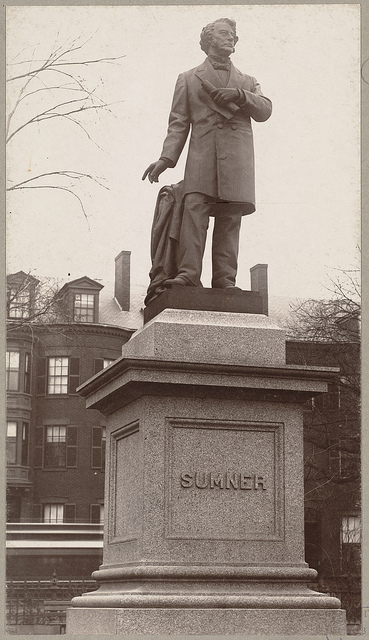

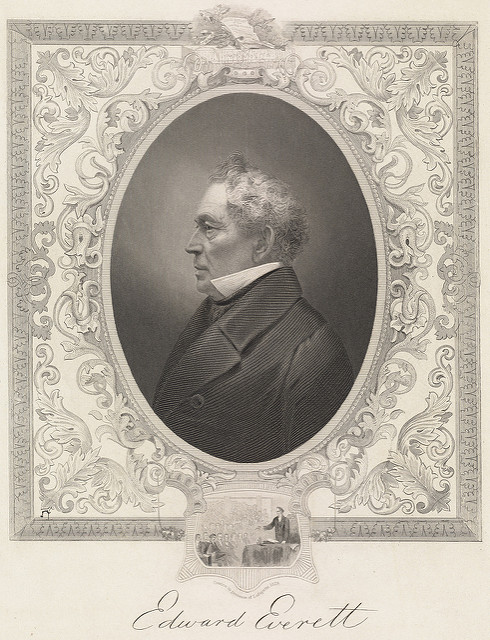

Congressional reaction to the Bloody Kansas situation is captured in this shocking and unsettling image by Winslow Homer. It evokes the rising tensions among abolitionists and slave owners in the years preceding the Civil War. The cartoon depicts an infuriated Preston Brooks, Representative from South Carolina, beating Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner with a cane on the floor of Congress. The beating was in retaliation for Sumner’s anti-slavery speech “Crime against Kansas“ delivered May 19-20, 1856. The sarcastic use of the word “chivalry“ in the cartoon’s title expresses northern views that the graceful and refined manners of southern gentlemen were disingenuous, considering many owned slaves. With this violent assault, Brooks succeeded in positioning Sumner as a martyr for the anti-slavery cause.

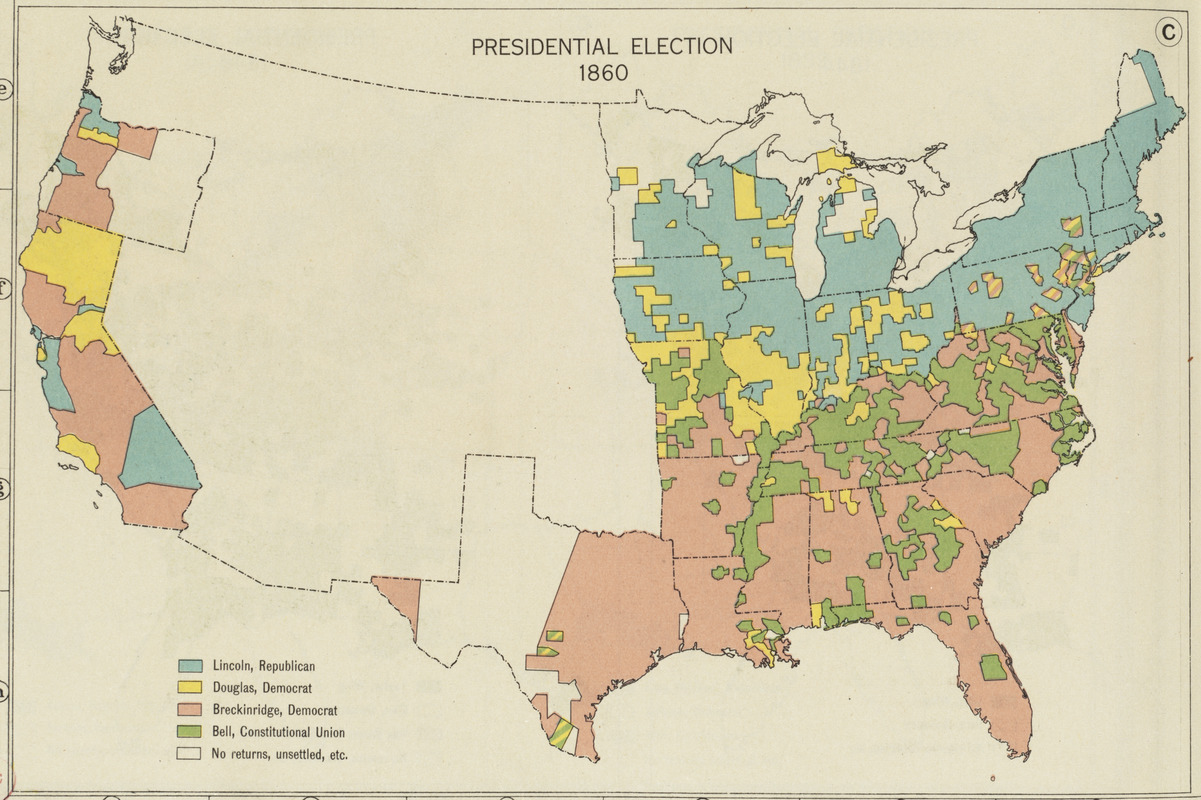

Charles O. Paullin and John K. Wright

"Plate 105C, Presidential Election 1860" in Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States

Washington, DC and New York: Carnegie Institution and American Geographical Society, 1932.

Courtesy American Geographical Society.

These reconstructed maps, precursors to contemporary news maps which provide instantaneous updates to election returns, depict the results of the Presidential election in 1860. This map, which was prepared for the nation’s first historical atlas, highlights the political tensions that underlay the strong sectional differences contributing to the Civil War.

The 1860 race, won by Republican Abraham Lincoln, had four major candidates, two supported by the North and two by the South.

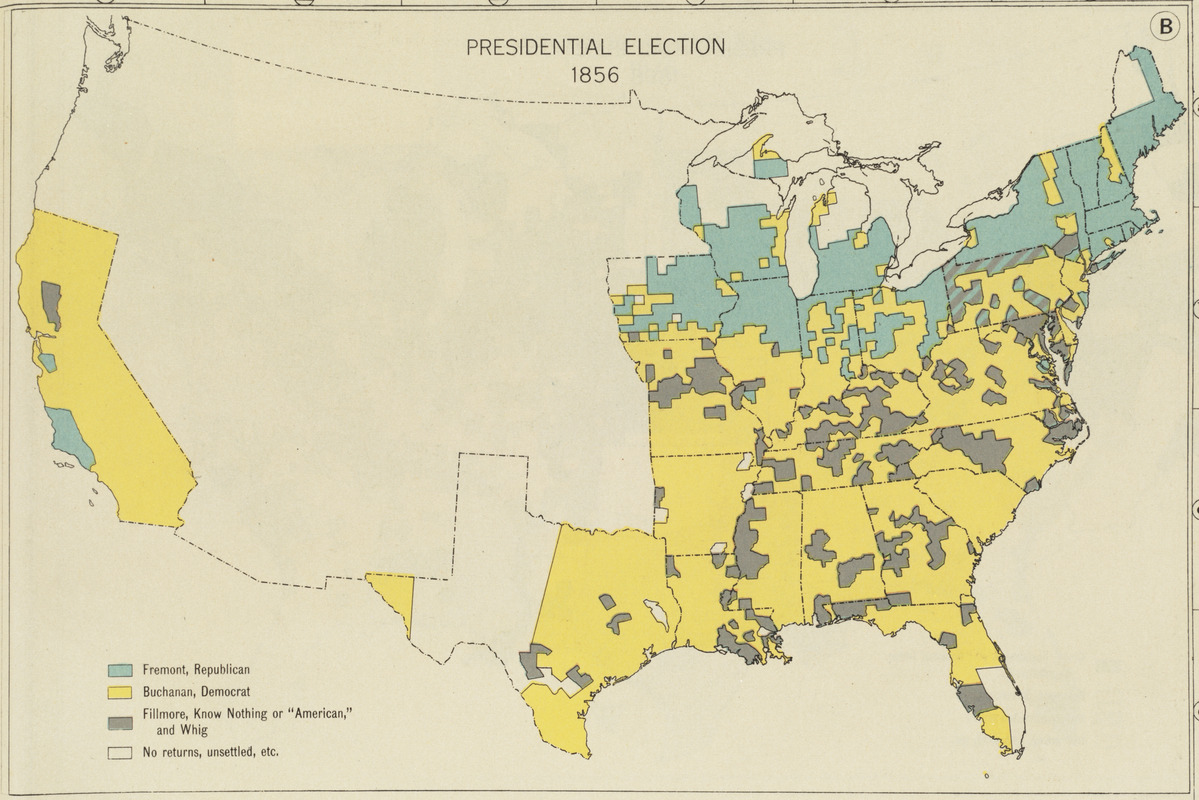

Charles O. Paullin and John K. Wright

"Plate 105B, Presidential Election 1856" in Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States

Washington, DC and New York: Carnegie Institution and American Geographical Society, 1932.

Courtesy American Geographical Society.

These reconstructed maps, precursors to contemporary news maps which provide instantaneous updates to election returns, depict the results of the Presidential election in 1856. This map, which was prepared for the nation’s first historical atlas, highlights the political tensions that underlay the strong sectional differences contributing to the Civil War. The 1856 election, marking the origins of the Republican Party, was a three-way race with Democrat James Buchanan claiming victory.

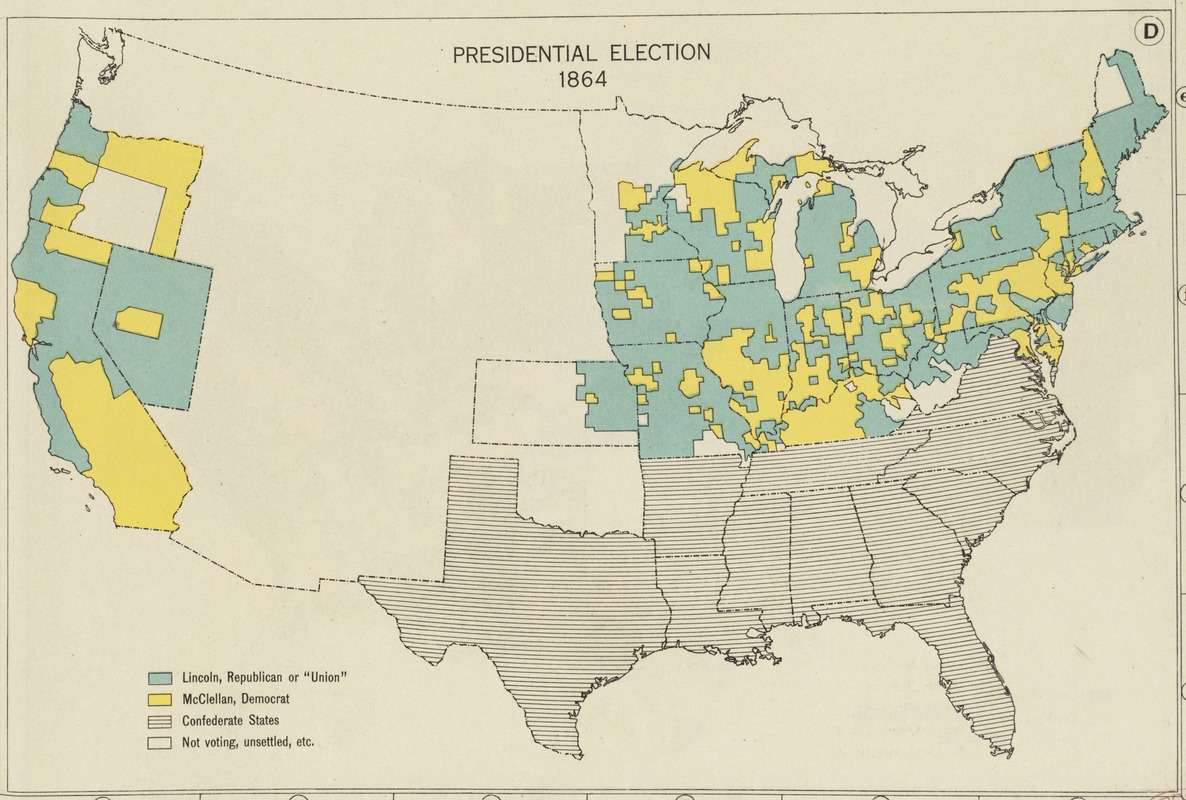

Charles O. Paullin and John K. Wright

"Plate 105D, Presidential Election 1864" in Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States

Washington, DC and New York: Carnegie Institution and American Geographical Society, 1932.

Courtesy American Geographical Society.

These reconstructed maps, precursors to contemporary news maps which provide instantaneous updates to election returns, depict the results of Presidential election in 1864. This map, which was prepared for the nation’s first historical atlas, highlights the political tensions that underlay the strong sectional differences contributing to the Civil War. With the seceded southern states not voting in 1864, the race was between Lincoln and his Democratic opponent George McClellan.

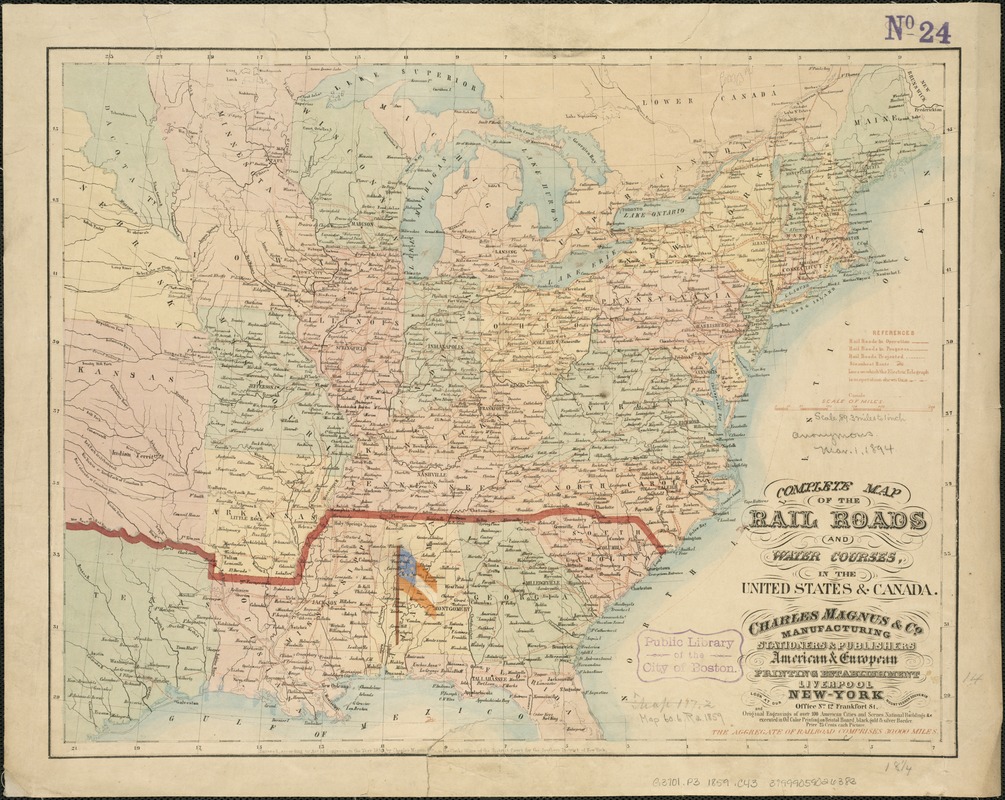

Charles Magnus

Complete Map of the Railroads and Water Courses in the United States and Canada

New York, 1859.

As sectional tensions increased during the late 1850s, there was rising sentiment among the southern states advocating secession. However, the spark that ignited the secessionist movement was Republican Abraham Lincoln’s victory in the Presidential 1860 election. Fearing the loss of their rights as slaveholders, seven states seceded and formed the Confederate States of America with Jefferson Davis as President.

Originally published in 1859, this rare railroad map was overprinted to show the first states to secede. The initial boundary of the Confederacy is marked by a heavy red line. Also depicted is the first flag of the Confederate States of America, the Stars and Bars. It was placed over the state of Alabama, signifying Montgomery as the first capital of the Confederacy.

2. During the War: A Nation in Conflict

The Civil War was unlike any other in US history. Fought completely on America soil, armies were most successful when they had accurate knowledge of the terrain. The South troops had an early advantage, not only because they had superior military leaders, but because most of the battles occurred on their home territory. Thus, they needed to wage a defensive campaign only. Reliable cartographic information was limited or absent and severely hindered the Northern efforts, often resulting in high casualties.

The war was all encompassing and every American had a personal stake in its course. Soldiers were recruited, supplied, trained, and transported. Casualties were high and many civilians came forward to care for the wounded. Those on the home front raised money, provided comfort and longed for news of their loved ones. Advances in technology, communication and transportation brought this information to them quickly and graphically. Visual images such as maps, photographs, cartoons and prints told the story as it unfolded. Traditional means such as letters, diaries and sketches also provided detailed accounts of the conflict.

Hear Our Stories

Follow twelve individuals who come to life as they tell their experiences before, during and after the war. They are fictional characters but their stories and the history surrounding them is real. Which person interests you most? Which person is most like you? Whose side do you think you would be on?

I can’t stop throwing up. Truth be told I’ve been crying too but I keep putting more dirt on my face to cover the tears. Why did they tell us we were going to fight a weak enemy who would disappear in six months? We ran today, like rabbits from the fox, as if we were the weak ones. We came to Bull Run and the first thing we saw were carriages and ladies and picnic baskets. People came out to watch the battle as if it were entertainment. It was grand to see them run faster than we did!

My buddy Aaron, right next to me, was hit by cannon fire. God forgive me, I can hardly speak it, but it crushed him until there was nearly nothing left. I must never tell his mother. I even threw up in front of our lieutenant, but he was even younger than I am and he was throwing up too. He put his hand on my shoulder and we both wept together. I found out later that Aaron was going to marry his sister.

I am shaking with excitement and fear. Louisa and I became nurses taking care of the brave men at war. We won’t be paid, but it will give us important work to do. Many of our class are doing this so we will not be looked down upon for “working.“ They say the Army doesn’t want us, but when they see what we can do, they may treat us with courtesy. I am lucky to be taken! Activist Dorothea Dix’s recruits are required to be middle-aged and plain, but Louisa vouched for me. I had to grow used to death and violence with no delay, and I will never remove the stains of gore on my apron. The wounded’s agony broke my heart and called me to give my best. Whether I write letters for them or hold a hand until the last breath of life, I know I am doing God’s work and serving my country. There are thousands of us nurses – surely this will bring change to our world after the war!

The Yankee is as heartless a devil as ever lived. While their cities see skirmishes, ours are destroyed. Charleston is home to the very bravest of us, Richmond too, people who will fight to the very end against every odd they are battered with. What kind of men can blockade and starve the women and children of a city? Are they so afraid of meeting our forces that they will kill the weakest among us? They have great force and artillery and more supplies, as they rake and raze their way through our lands. My land is reduced to charred fields, as they burn anything they cannot steal. The horses, any scrap of food, the cows and chickens, all gone. Our slaves have fled. It cannot be because of poor treatment so I believe they were kidnapped by Yankees and made to serve as soldiers.

We are unlucky soldiers or maybe just bad ones. We were assigned to guard an ammunition wagon and an ambulance. But the Federals were hidden like the Swamp Fox along the road. (We Tar Heels know the story of the Swamp Fox well.) They hid behind trees and bushes and even a fence along the road and mowed us down with their rifles and cannon. How will this war ever be over in six months? I notice the officers don’t say that anymore. By the end of today, one in three of us were gone. I prayed to God that night, for all of my regiment, for my family back home and especially for me. But there’s good news! We’re going to be transferred to the Light Division! And we were finally at luck in battle. We charged the federals at Gaines’ Mill and kept on charging until they retreated. But we mourn the loss of our colonel, killed by an artillery shell. Not a man didn’t weep openly for him.

What personal maid could survive such a rocky family! Who but a slave, who has no choice, would stay! Mrs. Davis has no rights to make any decisions, the eldest brother Joseph does that and it makes Mrs. Davis burn. And here I find myself in the home of the leadership of the Confederacy! We have moved to Richmond. Mr. Davis is the President and Mrs. Davis is First Lady. My mistress secretly thinks the Union will win so she is against the war but she can’t go about saying that, yet a lot of people know that’s what she thinks and she lost some of her popularity. She sees nothing wrong with slavery. She told me on my first day that I would be well treated by her family and I had nothing to fear about that. Well, every master thinks he is kind, and never understands that freedom is more precious than any kindness from Master. Mrs. Davis thinks we are an inferior race who needs to be taken care of.

Pa told us. They are Copperheads, like the poisonous snake, and they wear copper images of Liberty, cut from coins. They hate the war, and President Lincoln. They want peace by allowing slavery. They even attacked federal officers who came to town to draft men for the Army. Ma insisted that we boys be sent to Toronto where we could get work on farms until the war ended. Ma is Irish from way back. She told us about the times when the English sold Irish people as slaves to the Caribbean. Half a million of them. They were much cheaper than African slaves, who cost five times as much. She didn’t trust any one of English descent who was going to send the Irish to war. “We’ll be cannon fodder,“ she said. Copperhead newspapers cried for an end to war, a Union with slavery, and deposing Lincoln. They encouraged Union deserters and even had contacts with Confederate Army units.

My heart is pounding. A bunch of us slaves were taken by the Confederates to work for the Navy! We families are all below deck while topside the most daring thing I ever heard of is happening. Robert Smalls, pilot, (a slave who is hired out!) is about to steal this boat and get out of Charleston Harbor. He took the captain’s hat and stood on deck in the dusk, with his profile and the hat fooling everyone watching as he steered us to the Union ships. He’s the best pilot on the coast and got the Planter through the shoals. We hoisted a white flag before the Union ships could fire. They welcomed us and the news of our escape spread all over the country, even to Harper’s magazine. Robert traveled all over and people came to here him speak, but then he went back, became a Union pilot and was a big part of their success. Imagine: we had stolen a Navy ship from only a hundred yards from the headquarters of General Ripley!

We had become a stop on the Underground Railroad! I knew about it because I heard adults talking about Harriet Tubman, a speaker at our Quaker Church, who was working hard to help slaves to get safely to the free states, and about Frederick Douglass, who not only spoke loudly about slavery but had two sons who were going to join the 54th regiment. Father hollowed out under the stairs leading to the second floor. Then he built a new wall with shelves on it. The shelves looked sturdy but could quickly move to reveal the door to the now secret room in our house. He filled the shelves with books and pretty things. I can’t believe anyone can fit in the secret room but whole families do. If nobody was following them I would bring them soup and bread as well as blankets when they arrived. They told me I was a hero! I knew they were the heroes but still, I went to bed dreaming of being crowned a hero queen.

Now that the war is on, I’m worried about what will happen to the mill. My family depends on my wages and I keep hearing that the mills will close. They can’t get cotton anymore for us to make into cloth. I got a letter from James, our friend from days in Kerry, who lives in the North End in Boston. He said they are going to draft immigrants to fight the war and he’s not going. James’s family were like slaves at home on a rich man’s farm and the man wouldn’t feed them when the Famine came. I would not say I love Lowell – I miss the green open land and the farm – but at least I have wages and two meals a day for now.

For the first time in the history of our country, we are to be conscripted. I guess our Confederate leadership thinks that states should be free to govern but people should not. It will not work where I come from. We will take to the woods with rifles before we join any Confederate regiment. Last night the farmers of our area met in secret to decide how to avoid being drafted. None of us can afford to hire substitutes, because the price is rising quickly and I wouldn’t be surprised if it goes as high as $5000. We can’t afford the $300 exemption fee either, and we don’t want to lie about our health to be exempt.

By the end of the night we had agreed to form our own militia to protect ourselves. Yes, we are stealing food from the plantations, because they expected to fight this rich man’s war with poor men’s blood. We even help Yankee prisoners to escape, and we all help each other to hide from the conscription.

Our seminary is closed. Father was pleased so I pray for his soul. But I have volunteered to work for Mr. William Lloyd Garrison to help produce his newspaper, The Liberator. I tried to volunteer with an empty heart for war, but was rejected for my poor eyesight. Now I fear for our lives. Mr. Garrison has already been tied and dragged through the streets, mobbed and nearly lynched. The newspaper’s whole print run was stolen, which he could ill afford. But God’s fire is strong in him and keeps me fighting, too, even if it means working the printing press with little protection from the inks and chemicals. Mr. Garrison speaks like a powerful preacher and some people call him the nation’s conscience. Today the President announced the Emancipation Proclamation! Mr. Garrison was at a concert and they stopped the music to cheer him and Mr. Lincoln.

Finally! We are the 54th Massachusetts, 600 strong! We left Battery Wharf with thousands of people cheering us and marching down with us from the State House – and we proved them right at the battle of James Island. Not that the Union won. But everyone is saying that we were brave and able and calling for more of us to serve! It’s a big change! But change is happening so slowly – when we first got here they had us doing manual labor instead of fighting and they pay us less than white men. Yet every one of us will fight to the death for the Union! William Carney, a God-fearing man who wants to be a minister, kept our flag safe while being shot three times at the battle for Fort Wagner. We rejoiced until we all heard the bitter news that Colonel Shaw is dead. I’ll never forget him, and I know he’ll live forever in the hearts of every man of the 54th.

2A. Geography of War

Terrain influenced strategies and often determined outcome. Knowledge of the landscape meant victory or defeat. There were few large-scale topographic maps of the theaters of war available to military strategists prior to engagement. These factors gave military leadership in the South an initial advantage, but the North created broad geographical strategies that would use its economic strengths, particularly the disruption of trade which included naval blockades, control of the Mississippi River, and destruction of supply routes. Both sides were determined to capture each other’s capital. Although Washington, DC, was threatened several times, the Confederate capital of Richmond remained an elusive goal until the war’s end.

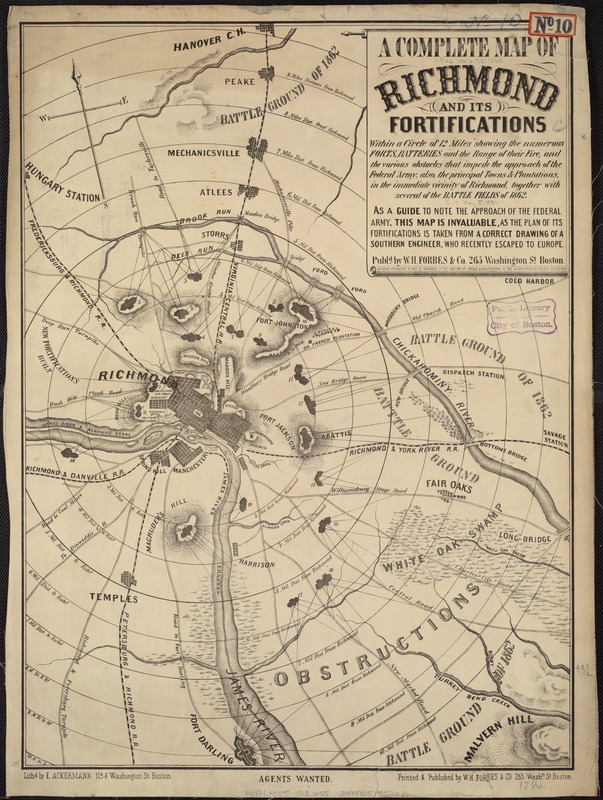

A Complete Map of Richmond and its Fortification

Boston: Forbes, 1863.

One of the geographic strategies for both armies was the capture of the other's capital. Washington, DC, was situated precariously on the Potomac River, sandwiched between Maryland, a slave state which did not secede, and Virginia, one of the last slave states to secede. As a primary defense, Union troops constructed an extensive ring of earthen forts around the city.

Richmond, which became the Confederate capital in mid-1861, was situated less than 100 miles south of Washington, DC. Confederate troops also fortified Richmond with a ring of forts, as depicted on this map published in Boston. As a reminder to a northern audience that Richmond was the target, the publisher placed a series of concentric rings around the city.

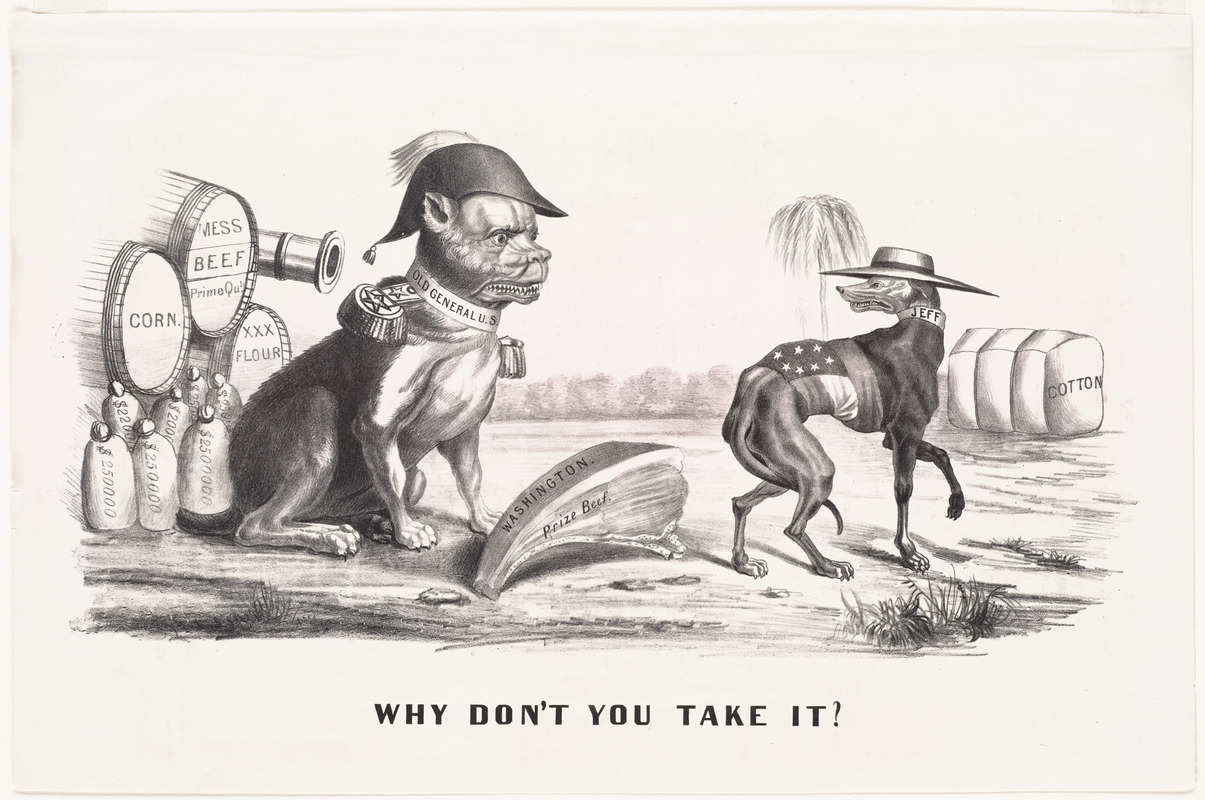

Why Don’t You Take It?

New York: Currier & Ives, 1861.

Print Dept.

In this political cartoon published by Currier & Ives, Gen. Winfield Scott, the first commander of the Union armies, is depicted as a fierce bulldog fronting the might of the North.

Supported by supplies, munitions and financial resources, he taunts the sheepish greyhound “Jeff.“ A great juicy bone labeled “Washington Prize Beef“ rests between them, and Scott asks “Why don’t you take it?“ as the Confederate leader slips away with his tail between his legs toward his meager supply of cotton. The cartoon suggests that the South had cotton but not many other resources, and did not have the means to seize the bone, or the capital city of Washington.

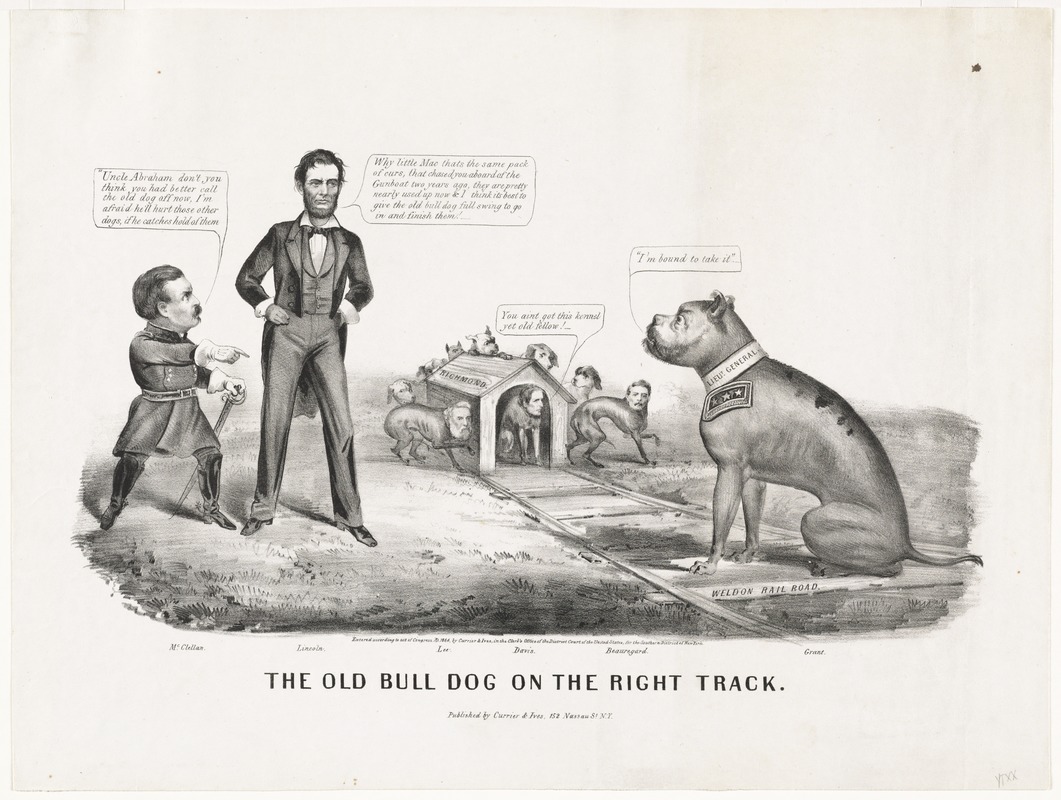

The Old Bull Dog on the Right Track

New York: Currier & Ives, 1864.

Print Dept.

This cartoon was published during the 1864 election year. It contrasts the military shortcomings of Gen. George McClellan, the second commander of the Union armies and the 1864 Democratic Presidential candidate, to the victories of his successor, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant.

Portrayed as a bulldog, Grant sits on railroad tracks leading to Richmond, represented by a doghouse in which Jefferson Davis cowers. Grant proclaims to Lincoln “I’m bound to take it.“ Davis, surrounded by Generals Lee and Beauregard responds, “You ain’t got this kennel yet old fellow.“ Grant finally seized Richmond during the first days of April 1865, bringing the war to an end.

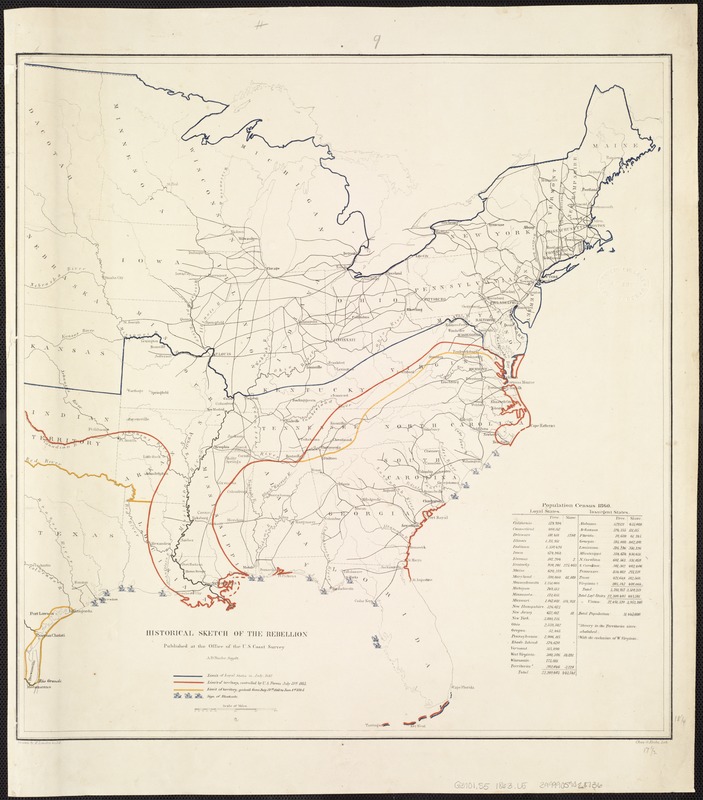

Henry Lindenkohl

Historical Sketch of the Rebellion

Washington, DC: U.S. Coast Survey, 1864.

In pursuing Scott’s broad geographic objectives, Union armies made substantial progress in blockading the southeastern coastline and occupying the Mississippi River. This tactic created an economic hardship by greatly diminishing commerce with Europe. With control of the Mississippi Valley, they split the Confederacy, cutting off supply routes particularly from Texas and Arkansas. In order to demonstrate the progress of this strategy, the U.S. Coast Survey published at least seven maps with the same title, “Historical Sketch of the Rebellion,“ each delineating Union military progress. By early 1864, the North had gained control of the entire Mississippi River Valley, blocked most southern ports, and had occupied much of the Texas, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina and Virginia coastal areas.

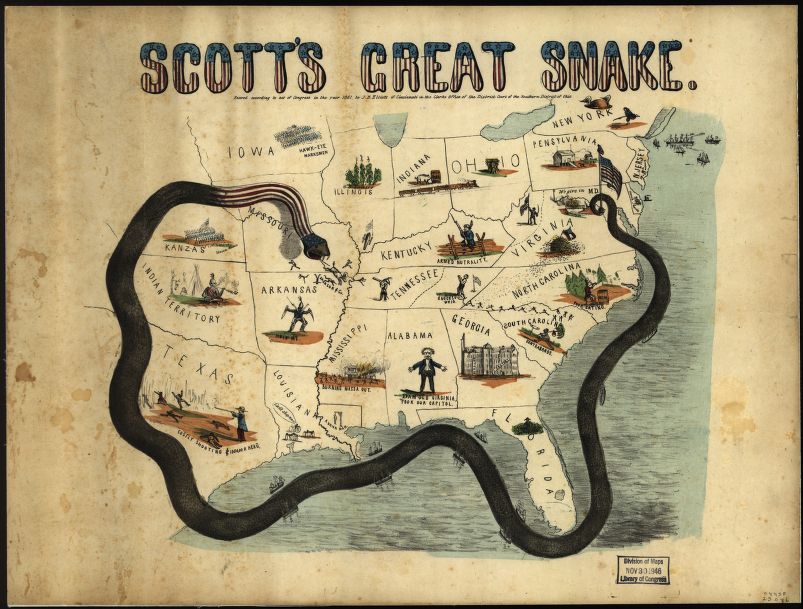

J.B. Elliott

Scott’s Great Snake

Cincinnati, 1861.

Reproduction courtesy Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress.

In the spring of 1861, when war was inevitable, Union Army General-in-Chief Winfield Scott devised a long-term strategy to economically and militarily crush the Confederacy. The plan called for a naval blockade of southern ports and a major offensive down the Mississippi River, thereby cutting off supply routes and dividing the South. Scott’s tactic was dubbed the “Anaconda Plan,“ as it was intended to constrict the insurgent States, as would a snake. The plan was depicted graphically in this 1861 pictorial map. Although not prevalent during the Civil War, propaganda maps such as this were designed to have maximum emotional effect on the user, as more civilians became aware of wartime activities.

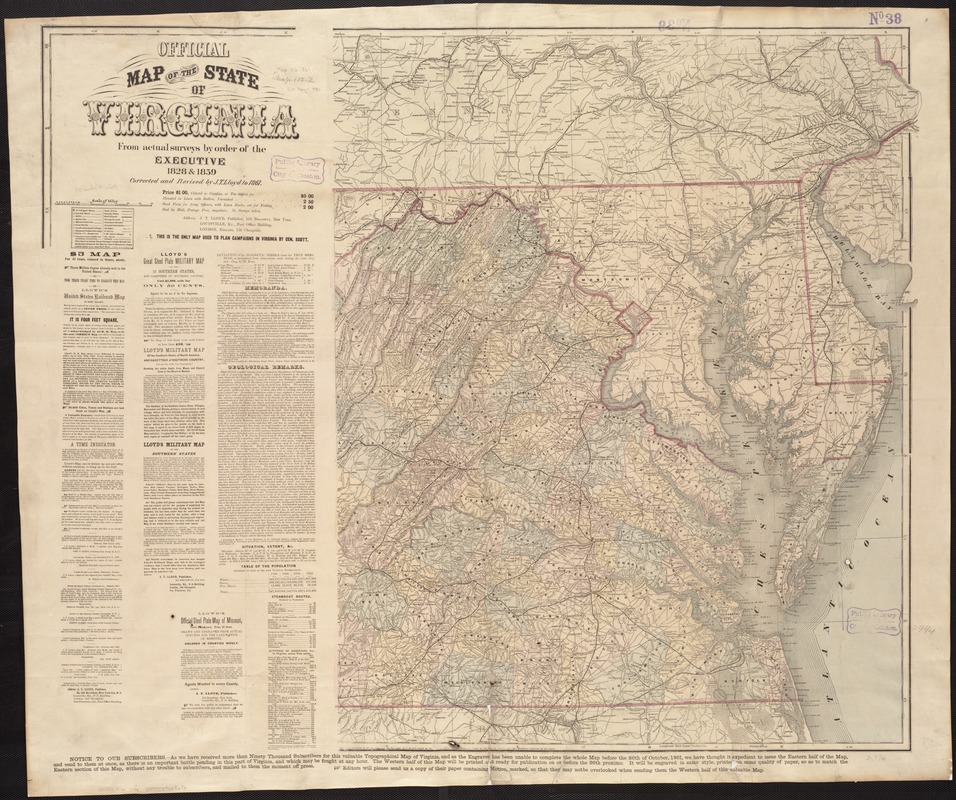

J.T. Lloyd

Official Map of the State of Virginia from actual surveys by order of the Executive, 1828 & 1859

New York, 1861.

At the beginning of the war, few detailed topographic maps were available to officers for planning movements and engagements. In addition, some moderate-scale state maps, which could be used for planning broader regional strategies, were out-of-date. This was especially true for Virginia, where many of the battles were fought. Although this 1861 Virginia map claims to be official, accurate and current, the title is misleading. It was not an official state publication; rather it was produced by a commercial firm located in New York City. It was derived from an 1859 state map, which was a hurried revision of an earlier 1828 state map. The latter map did incorporate county surveys, but they were inconsistent in scale and data collected.

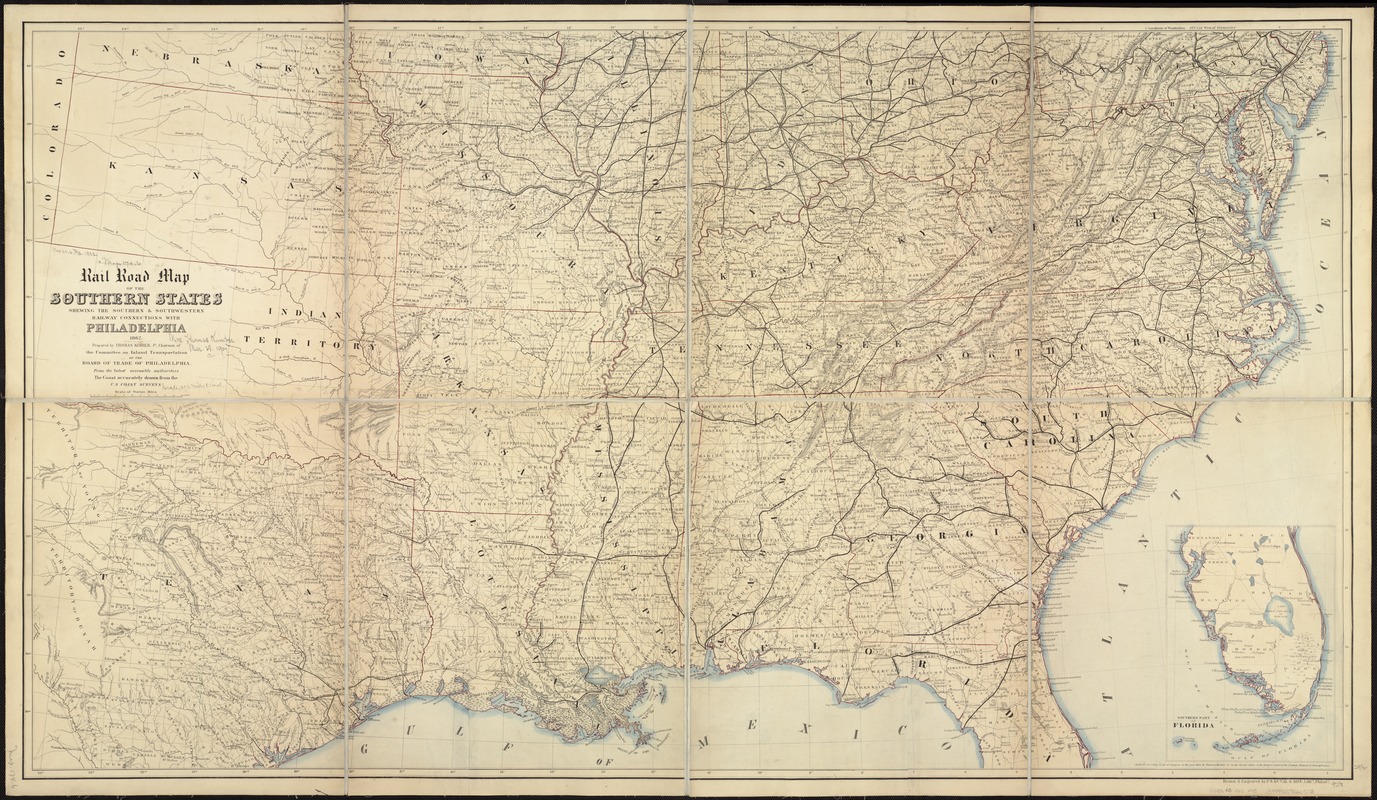

Thomas Kimber

Rail Road Map of the Southern States Shewing the Southern and Southwestern Connections with Philadelphia

Philadelphia, 1862.

While this appears to be a fairly typical mid-19th century railroad map, it was specifically commissioned by the War Department to provide current information about southern railroads. The map’s significance for military intelligence was recorded in a note written by the cartographer’s widow when she gave this copy to the Boston Public Library.

She recalled that the map was displayed in Secretary Stanton’s War Office, where black and red pins were used to locate the varying positions of the two armies, and that the map proved very useful to General Sherman in his march through Georgia to the sea. Mrs. Kimber concluded by stating her husband was a Quaker “and to ease his conscience for having prepared such a map at all he declined any payment for it.“

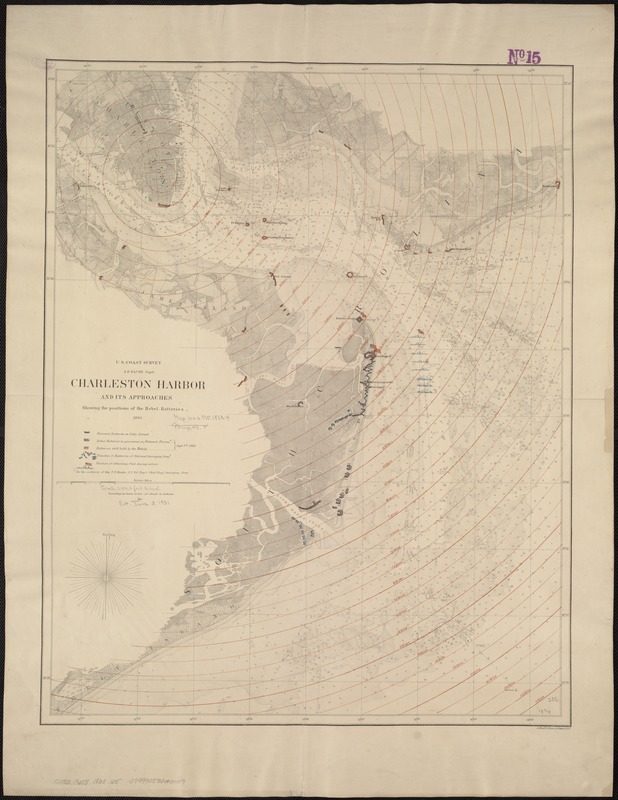

Charleston Harbor and its Approaches, Showing the Positions of the Rebel Batteries

Washington, DC: U.S. Coast Survey, 1863.

Anticipating war, the U.S. Coast Survey was one of the few agencies able to provide accurate nautical charts and topographic maps before and during the war. Led by Alexander Dallas Bache, the nation’s foremost scientist and great-grandson of Benjamin Franklin, the agency’s primary mission was to chart the nation’s coastal waters, and by the 1850s was beginning to produce detailed nautical charts for most of the Atlantic and Gulf coastal waters. One example is this chart of South Carolina’s Charleston Harbor published in 1863. Utilizing an 1858 chart, which was based on detailed hydrographic and topographic surveys conducted in the early 1850s, this version was overprinted to show forts, “National“ and “Rebel“ trenches and batteries, and positions of the attacking fleet as of September 7, 1863.

2B. Living Room War

From today’s perspective, many regard Vietnam as the first “living room” war, with evening television programs bringing the latest news to kitchen tables and living rooms across America. But the Civil War was really the first! Just as we go online or watch CNN for immediate updates on the current conflict, those on the Civil War home front looked to newspapers and magazines for current news on the war. The press told this story with words and images by publishing cartoons, photographs and sketches. Theater of war and battle maps allowed viewers to follow troop progress. Personal communication, such as telegrams, soldiers’ letters, and diaries, brought poignant accounts of war.

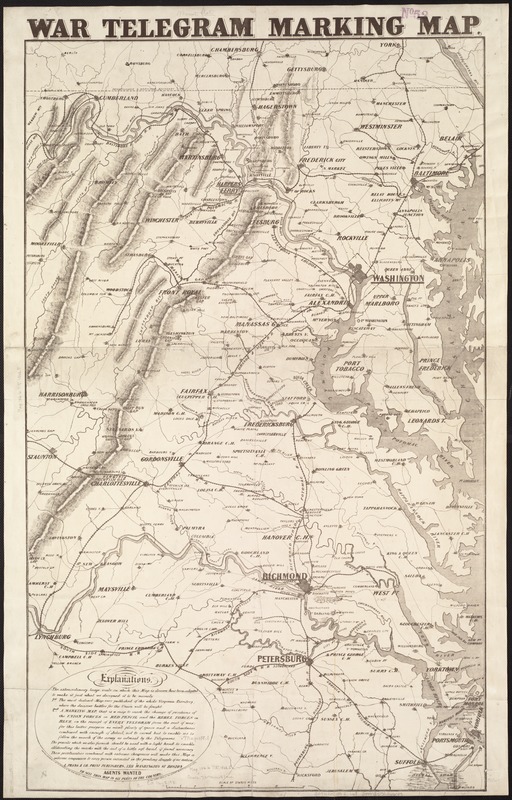

War Telegram Marking Map

Boston: L. Prang, 1862.

During the war, commercial firms located in the North published a variety of war-related maps, primarily for the general public. One example, published in Boston, focused on the theater of war in Virginia and Maryland, where “the decisive battles for Union will be fought.“

As its title suggests, it was to be used by those following the progress of the war when they received news by telegram, a new technology which gained wide acceptance during the 1840s and 1850s along with the nation’s expanding railroad network. The small legend in the lower left also indicates that it was sold with colored pencils so that movements of the Union forces could be marked in red and those of the Rebel forces in blue.

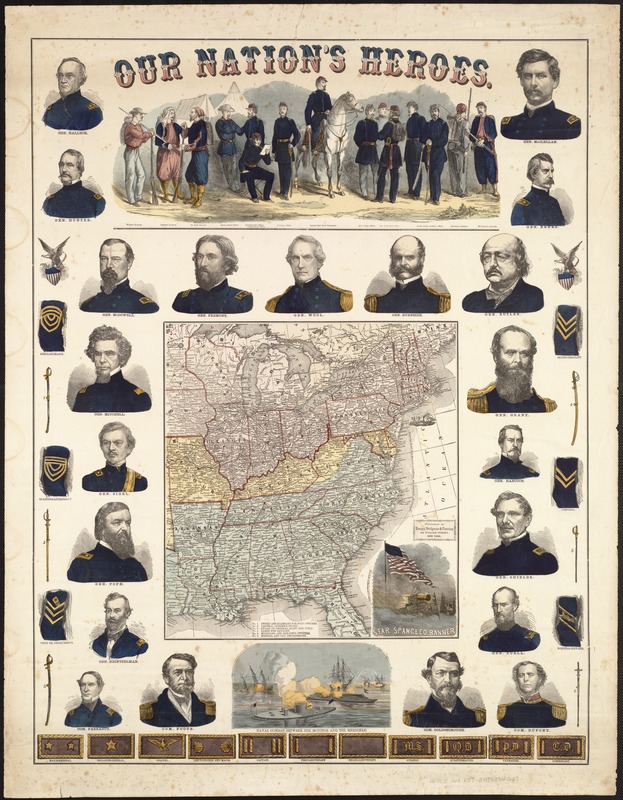

Our Nation’s Heroes

New York: Ensign, Bridgman and Fanning, 1863.

Most likely published as a commemorative souvenir fostering northern patriotism, this colorful broadside displays an array of graphic illustrations intended to appeal to a living room audience. The central focus is a small map of the eastern United States. Although it does not identify the Confederate states as a separate nation, the seceded states were colored blue and the border slave states which did not secede yellow.

The marginal illustrations include portraits of 21 Union generals and commodores, as well as a variety of military memorabilia. There are also three vignettes – one depicting fourteen soldiers dressed in different Union uniforms, another illustrating the battle between the two ironclad ships Monitor and Merrimack, and the third, a symbolic representation of the Star-Spangled Banner flying gloriously over a battle scene.

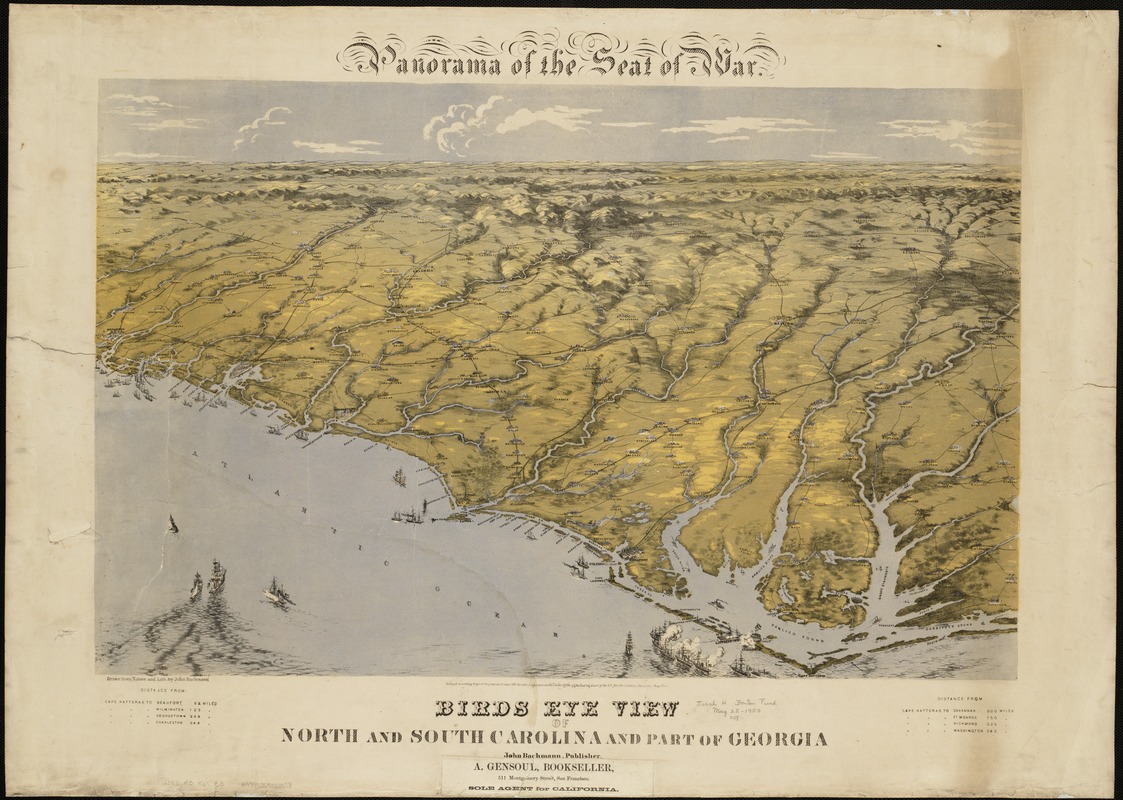

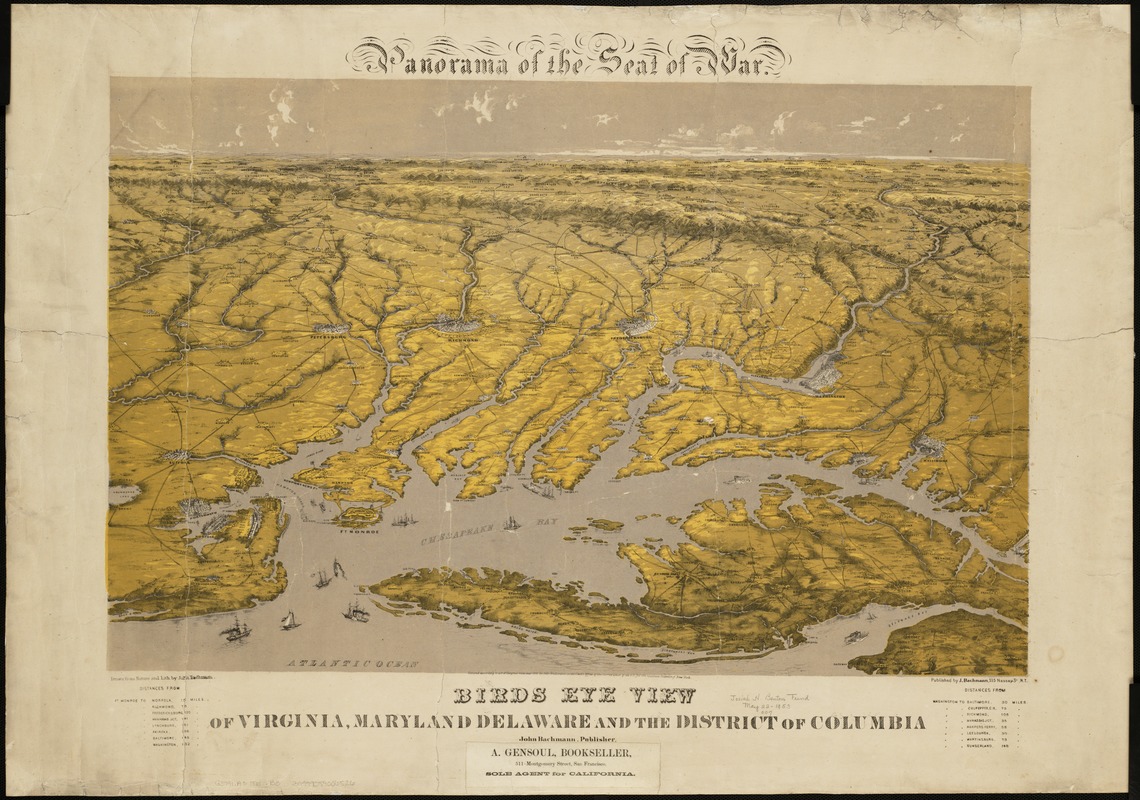

John Bachmann

[LEFT] Panorama of the Seat of War, Bird’s Eye View of Florida and part of Georgia and Alabama

[CENTER] Panorama of the Seat of War, Bird’s Eye View of North and South Carolina and part of Georgia

[RIGHT] Panorama of the Seat of War, Bird’s Eye View of Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, and the District of Columbia

New York, 1861.

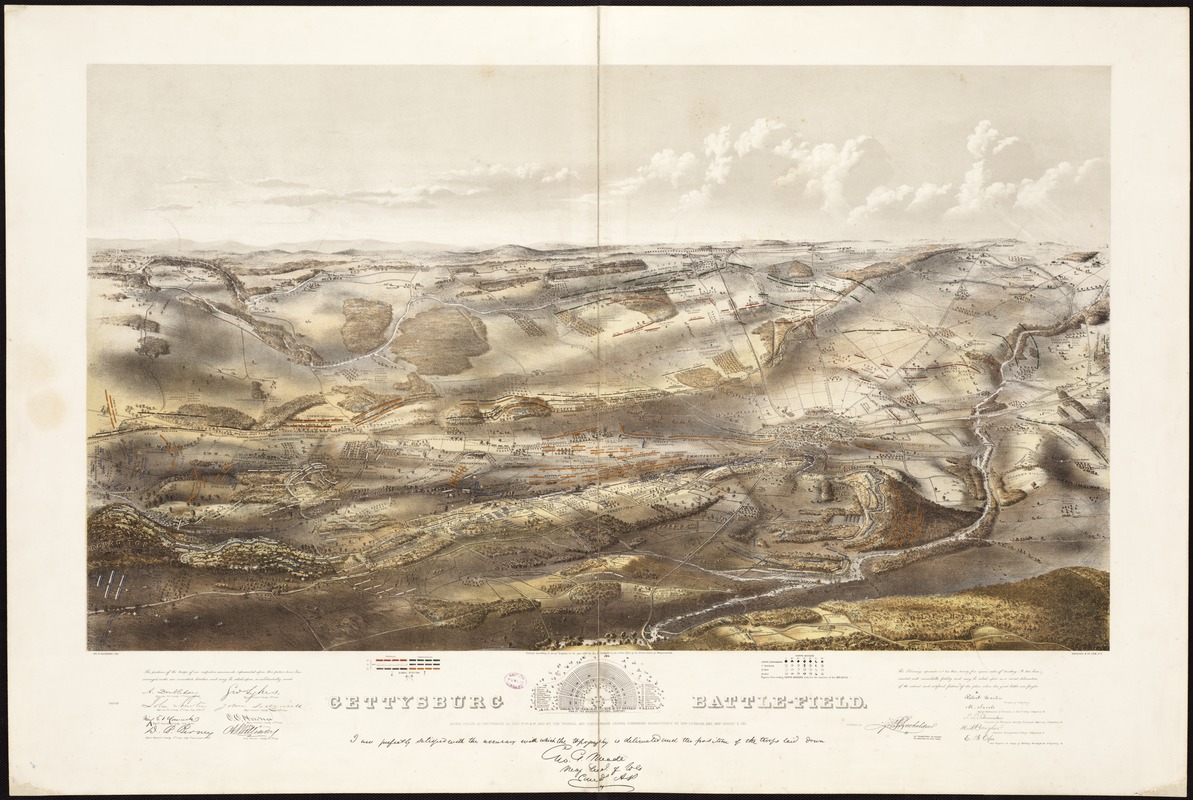

Three separately published bird's-eye views provide a continuous panoramic perspective of the southeastern United States coast, extending from the Chesapeake Bay to Florida. Together they highlight the Union naval blockade of the Confederacy, showing pictorially coastal fortifications as well as ships lining the coast and entering major harbors.

It is truly remarkable that these views were the work of one man, Swiss born artist John Bachmann, because he did not have the ability to observe such a large part of the country from an elevated perspective, other than in his own creative imagination. While not particularly useful for planning military maneuvers because of exaggerated topography and inconsistent scales, they were intended to assist a living room audience in visualizing the geographic areas where the battles had and would occur.

Thomas Nast

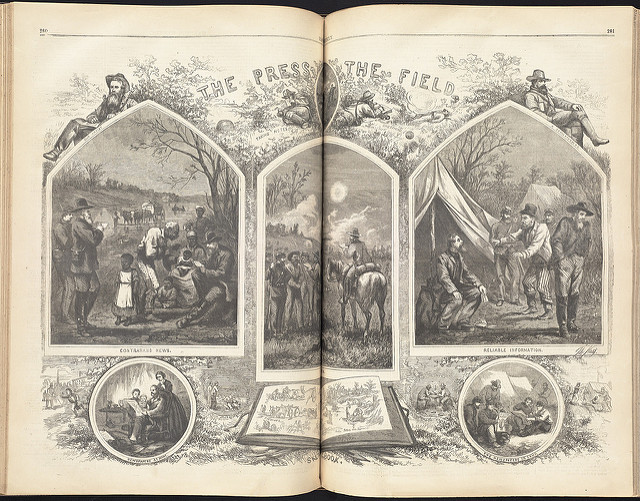

"The Press on the Field," from Harpers Weekly, April 30, 1864.

Rare Book Dept.

During the Civil War, more than 2,000 maps appeared in Northern daily newspapers. In contrast to previous journalistic practices, this production represented a remarkable increase in number and variety. Prior to the war, maps rarely appeared in American newspapers, and those that did tended to be small and diagrammatic. The expansion of railroad and telegraph networks and advances in printing technologies during the 1850s facilitated this revolution in journalistic cartography.

To broaden their coverage of the war, newspapers greatly expanded their press corps by adding correspondents to their payrolls. Consequently, an important component of army camps was the press, or as Harper’s Weekly referred to them, the “newspaper brigade.” In Thomas Nast’s 1864 engraving for the magazine, correspondents were depicted in numerous vignettes obtaining news from contrabands, embedded with soldiers on the field, and skeptically listening to "reliable information." For those reading Harper's Weekly back home, this view depicts the journalist’s life at the front, and overall is a comprehensive representation of how the popular media covered the war.

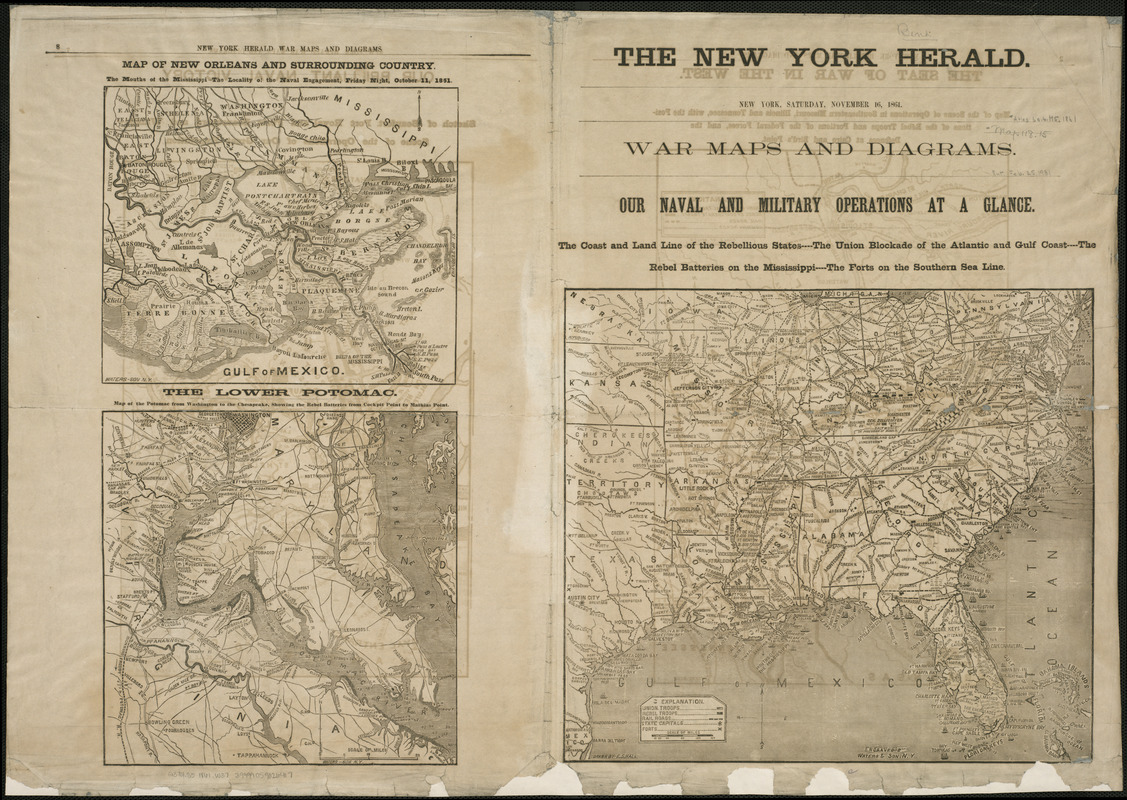

“War Maps and Diagrams,” from The New York Herald

November 16, 1861.

During the Civil War, more than 2,000 maps appeared in northern daily newspapers, representing a remarkable increase in number and variety. They ranged from large-scale plans of fortifications and battles to small-scale campaign and theater of war maps. Prior to the war, maps rarely appeared in American newspapers, and those that did tended to be small and diagrammatic. This variety is well represented in an eight-page map supplement published by The New York Herald. The supplement’s front page displays a general reference map highlighting the naval blockade of the southeastern coast, while the opposing page presents two more detailed maps depicting New Orleans and the Lower Potomac. There are an additional fifteen maps in the supplement, including a large-scale depiction of Richmond and several plans of South Carolina fortifications.

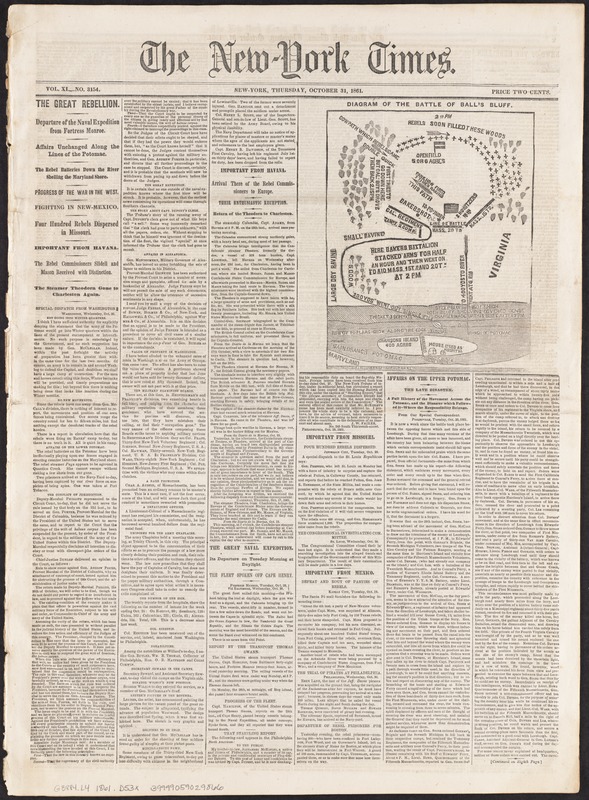

“Diagram of the Battle of Ball’s Bluff” in The New York Times

October 31, 1861.

This schematic map illustrates the nature of newspaper maps and their role in helping to inform the public of the progress of the war. Published on the front page of The New York Times ten days after the battle, it accompanied an extensive article about the Battle of Balls Bluff, which occurred on the banks of the Potomac River a few miles west of Washington, DC. What was supposed to be a diversionary maneuver while a larger Union force moved against Confederate troops encamped near Leesburg, Virginia, resulted in a disastrous retreat for Union troops, including both the Massachusetts 15th and 20th Regiments. The lack of good topographic information, which is almost totally lacking in this quickly prepared diagram, contributed to their defeat.

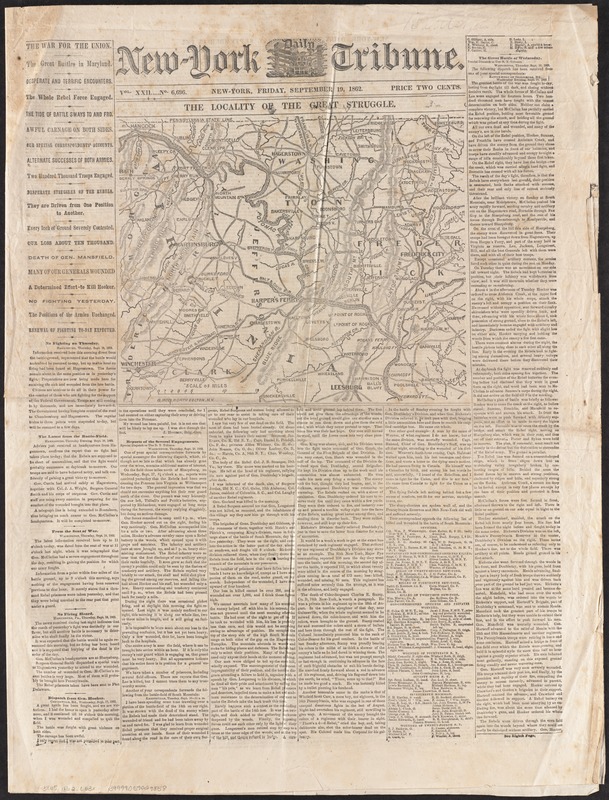

“The Locality of the Great Struggle,” in The New York Tribune

September 19, 1862.

The first major battle fought on northern soil occurred September 17, 1862, in Washington County, Maryland, about 50 miles west of Washington, DC. Known as Antietam Creek or Sharpsburg, it is now recognized as the bloodiest one-day battle in American history, with approximately 23,000 casualties.

Accounts of this battle started to appear in northern newspapers two to three days after the engagement. One of the earliest map-illustrated articles was published in the New York Tribune, September 19. Although this map did not attempt to depict the military action of the day, it did show the general location of Sharpsburg and the surrounding countryside along the upper Potomac River. The Tribune published a more detailed map of the battlefield in the next day’s issue.

Solomon Bamberger

Map of Battles on Bull Run, near Manassas

Richmond: West and Johnston, 1861.

The first major battle of the war occurred July 21, 1861, near Manassas, Virginia, an important railroad junction approximately 25 miles west of Washington, DC. This map, published in Richmond, is one of only a few examples of battle maps produced by a commercial publisher within the Confederacy. This relatively simple diagram used pictorial symbols and text to provide a detailed account of the battle. As indicated in the map’s title, the battle was known by various names. The Confederates, who named battles for nearby towns, knew it as the Battle of Manassas. For the Union army, which often named battles for nearby rivers or streams, it was the Battle of Bull Run.

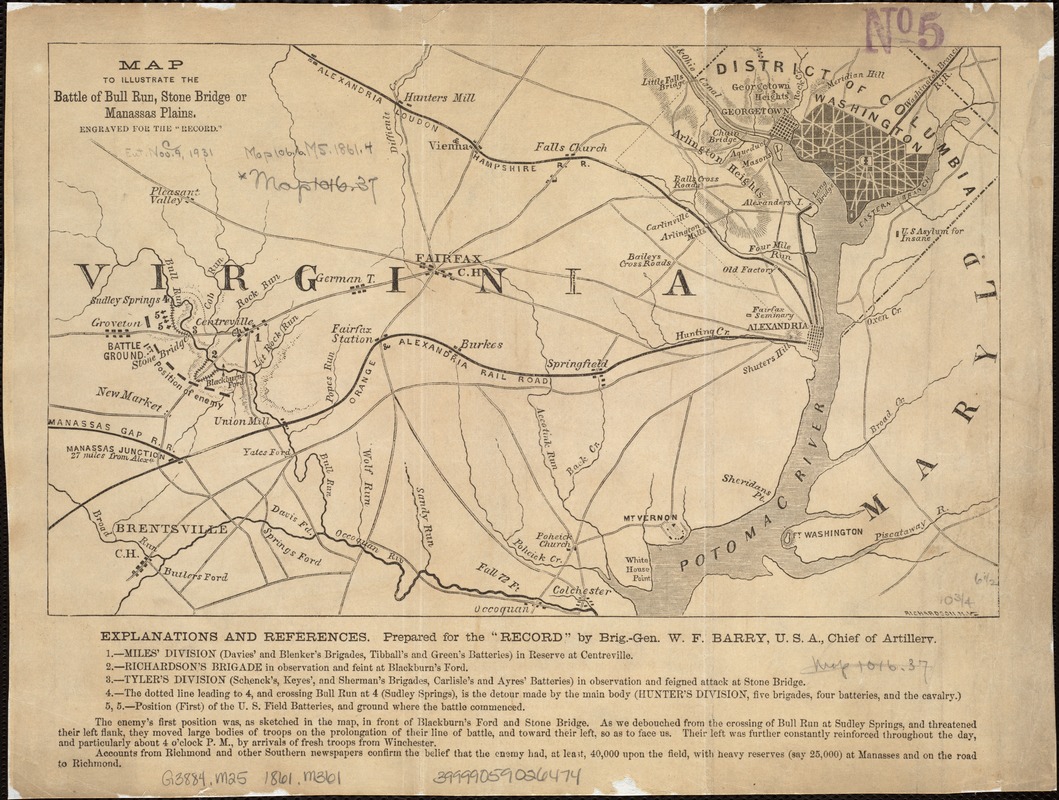

William F. Barry

“Map to Illustrate the Battle of Bull Run, Stone Bridge, or Manassas Plains . . .” from Rebellion Record, vol. 2

[New York, 1862].

This map, prepared by a Union artillery officer, focuses less on the battle action, but demonstrates its strategic significance in relation to Washington, DC. Charged with defending the nation’s capital, Union troops hoped to gain a quick victory over Confederate troops.

Anticipating that a Union victory would bring a speedy end to the war, citizens from the nation’s capital came in carriages with picnic lunches to watch the action. Unfortunately, the poorly trained Union troops suffered a humiliating defeat, and both sides realized that the war would not be resolved quickly.

Other names used for the battle, as reflected in the map’s title, were Stone Bridge and Manassas Plains. Another battle occurred in the same area, August 29-30, 1862, and subsequently was known as the Second Battle of Bull Run or Manassas.

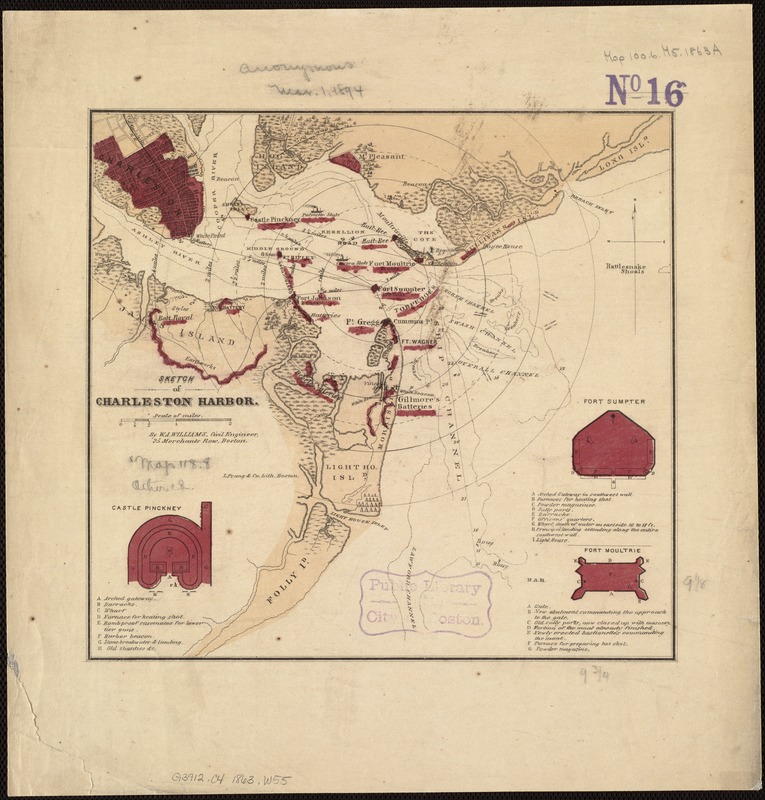

W. A. Williams

Sketch of Charleston Harbor

Boston: L. Prang, [1863]

The Confederate bombardment and Union surrender of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, April 12-13, 1861, marked the beginning of the Civil War. Since the city remained under Confederate control throughout the war, it continued to be an objective of Union military strategy.

Appealing to a northern audience following the Union army’s attempts to regain South Carolina’s primary port, Boston publisher Louis Prang issued four undated variations of this map. Each focused on Fort Sumter, surrounded by concentric circles at half-mile intervals, as if marking it a target for Union aggression. Published in 1863, this version documented Union operations from April to September, which included the heroic but disastrous assault on Fort Wagner by the Massachusetts 54th, the African-American regiment led by Robert Shaw, on July 18.

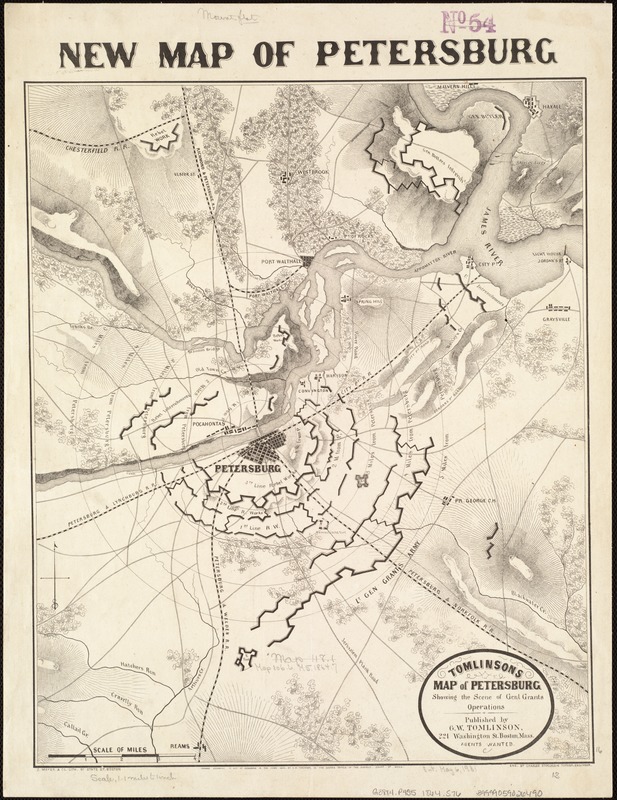

Tomlinson’s Map of Petersburg, showing the Scene of Genl. Grant’s Operations

Boston: G.W. Tomlinson, 1864.

In addition to newspaper maps, commercially published battle maps were available to folks on the home front for following the progress of the war. A number of such maps were published by Boston firms. For example, Boston publisher G.W. Tomlinson issued a map of Petersburg, Virginia, near the end of the war. Using a concentric ring overlay, it depicted the Union siege under the command of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, of this vital railroad center approximately 20 miles south of Richmond. The map clearly delineated the elaborate trench network that both sides constructed during the campaign. The assault began in June 1864 and lasted for ten months, the longest sustained operation of the war.

L. H. Russell

Map of the New Convalescent Camp, Fairfax Co. Va., four miles S.W. of Washington, DC

Philadelphia: E.J. Maddox, 1863.

Casualties during the war were unprecedented with 620,000 dying. The number injured was also quite high, and their care was an important priority, particularly for organizations determined to bring modern sensibilities to such undertakings. Among these was the newly formed U.S. Sanitation Commission, which attempted to shape the hygiene of camps, train nurses, and form ambulance corps.

This ground plan, reflecting many of their objectives, depicts a convalescent camp near Washington, DC. Buildings are placed in an orderly manner with efficient use of space and easy access. This plan reflects the vision of the Commission’s Executive Secretary, Frederick Law Olmsted who would become one of the great designers of public space in the post-bellum period.

Henry C. Blair

Hospital Slippers for the Sick and Wounded Soldiers of the Union

Philadelphia, 1861.

Reproduction courtesy Boston Athenaeum.

Those on the home front were eager to help in any way that they could. Everyone knew someone who was wounded or lost a son, brother or husband in the war. For those who were convalescing, the smallest gift might bring comfort.

As suggested by this printed slipper pattern, a pair of soft and warm slippers would be most welcome. The pattern was easily followed and for the price of a single postage stamp, they could be sent to a central location in Philadelphia and then distributed to those in need.

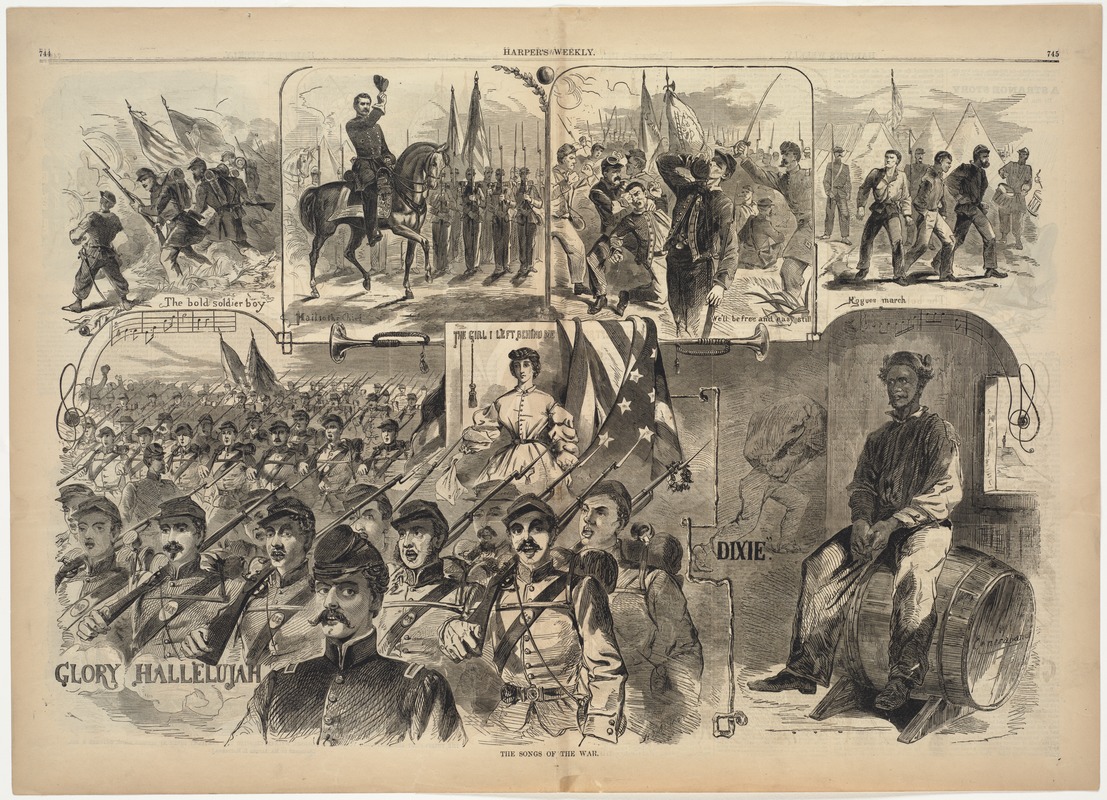

Winslow Homer

"The Songs of War," from Harper’s Weekly

November 23, 1861.

Print Dept.

The production of music scores quickly shifted to wartime needs after the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter. Composers rapidly produced “Songs of War,“ as suggested by this Winslow Homer illustration published in Harper’s Weekly. The image displays seven wartime songs, but it is dominated by a vignette depicting a multitude of soldiers marching to war and singing the chorus “Glory Hallelujah.“ Religious fervor was common in 19th century discourse. As the country divided, the rhetoric reflected the passion on both sides. The Battle Hymn of the Republic is a strong example of the juxtaposition of militancy and religion. Although a seeming departure from the pacifist Protestant reform spirit of the 1830s and 1840s, clergy on both sides exhorted troops to show no mercy on their enemy as they sought justice.

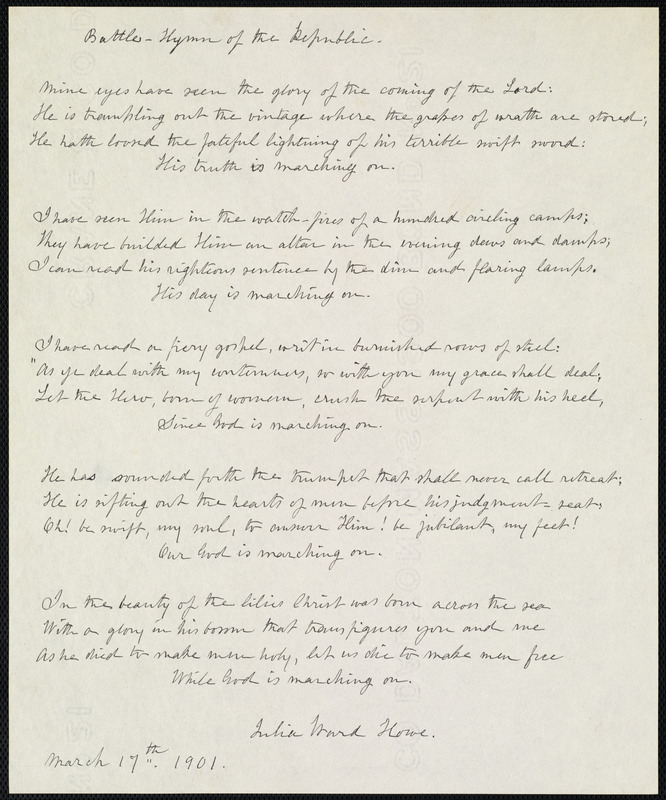

Julia Ward Howe

Battle Hymn of the Republic

Manuscript, signed and dated March 17, 1901.

Rare Book Dept.

Julia Ward Howe’s Battle Hymn of the Republic, written as an abolitionist poem, became very popular during the Civil War. After visiting a Union army camp near Washington, DC, in 1861, she was inspired by soldiers singing lyrics to a camp song that originated as a parody of John Brown, a soldier at Boston’s Fort Warren and John Brown, the abolitionist. Howe’s poem, which easily fit the same tune, was first published in The Atlantic Monthly in February 1862. Displayed here are the original lyrics that she recopied in 1901.

Along with her husband Samuel Gridley Howe, Julia Ward was active in the anti-slavery movement. Together they edited the abolitionist newspaper, The Commonwealth. Her husband was the director of the Perkins Institute for the Blind, then located in South Boston.

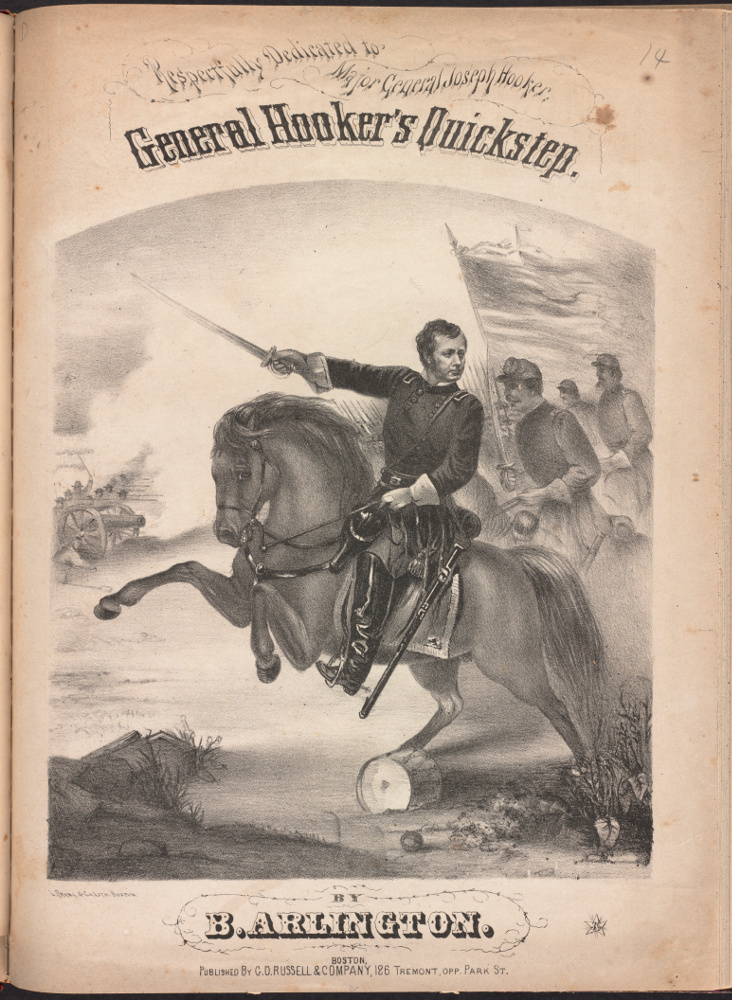

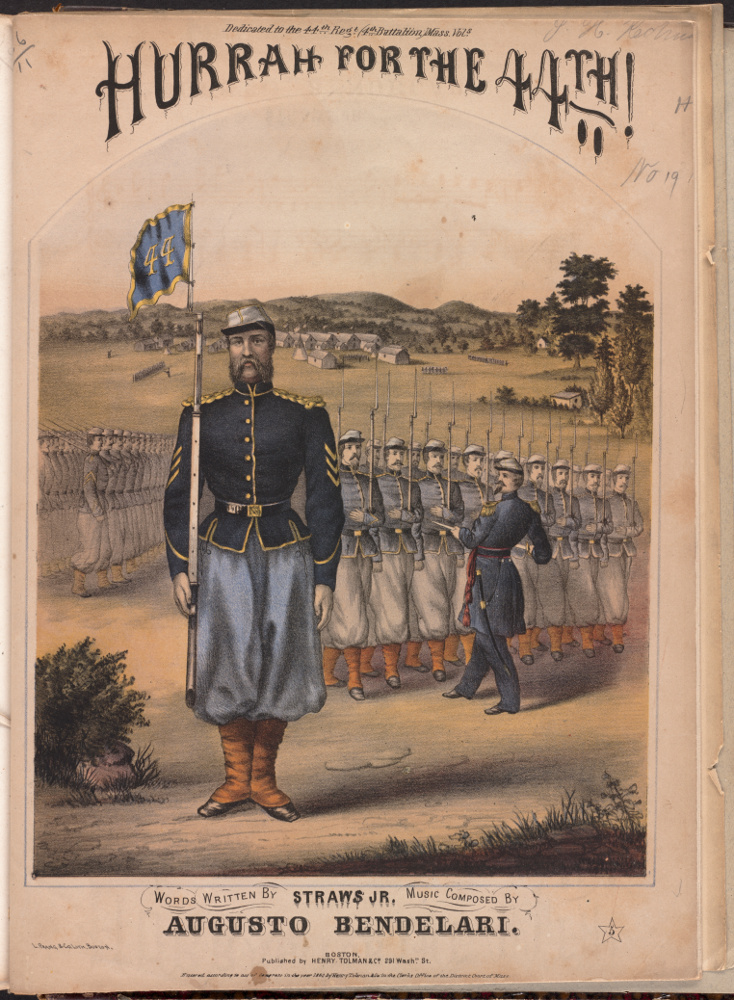

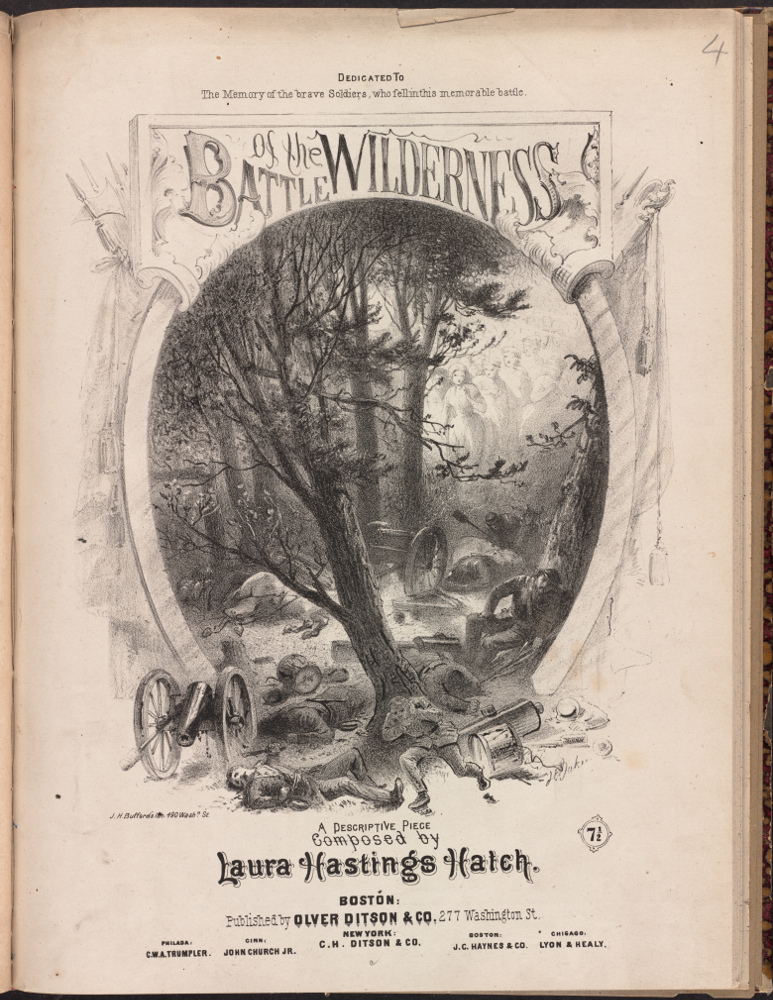

Printed sheet music increased in popularity during the middle of the 19th century as printing technologies improved and music playing in middle class homes became a fashionable pastime. Musical compositions relating to the Civil War, as illustrated by examples of sheet music published in Boston, highlighted the accomplishments of individuals such as Massachusetts-born Gen. Joseph Hooker, individual regiments including the Massachusetts 44th, and military campaigns, notably the Battle of the Wilderness. Decorative covers were added to the printed scores to adorn and advertise the lyrics. These war-time covers, which display powerful visual images, convey the glory and struggle of the conflict. They reminded those on the home front of the soldiers’ affections, the causes for which they fought, and the ne’er do wells they opposed.

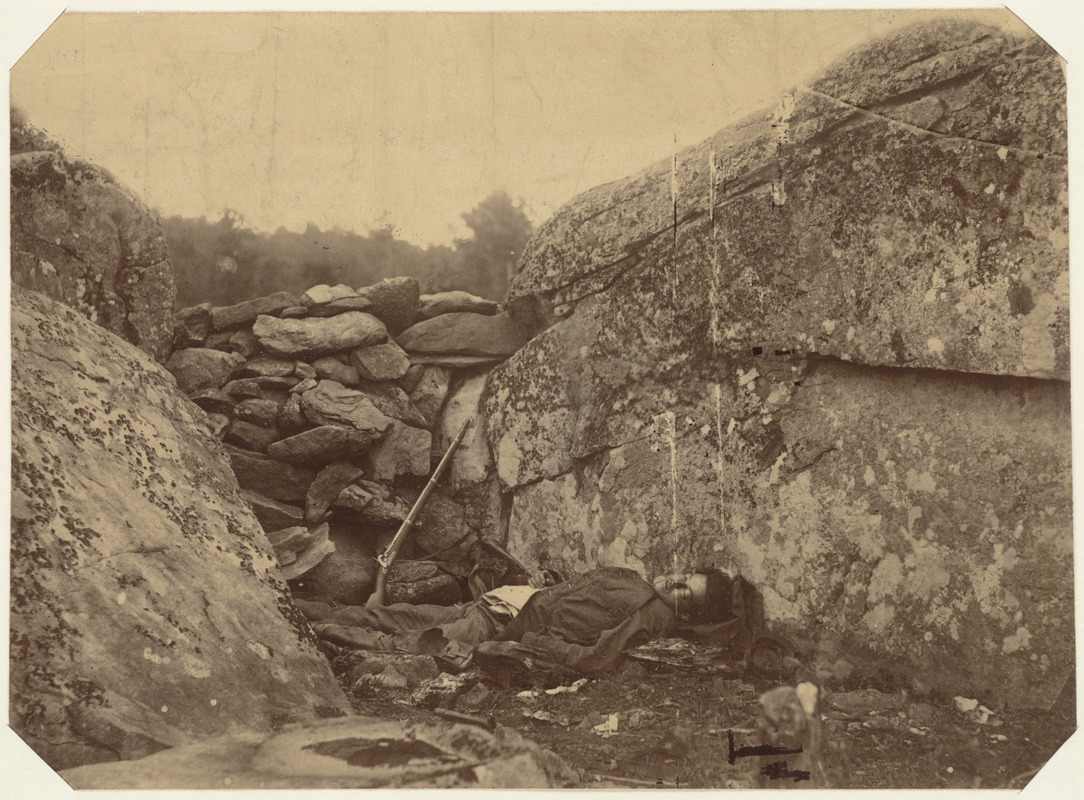

John C. Ropes

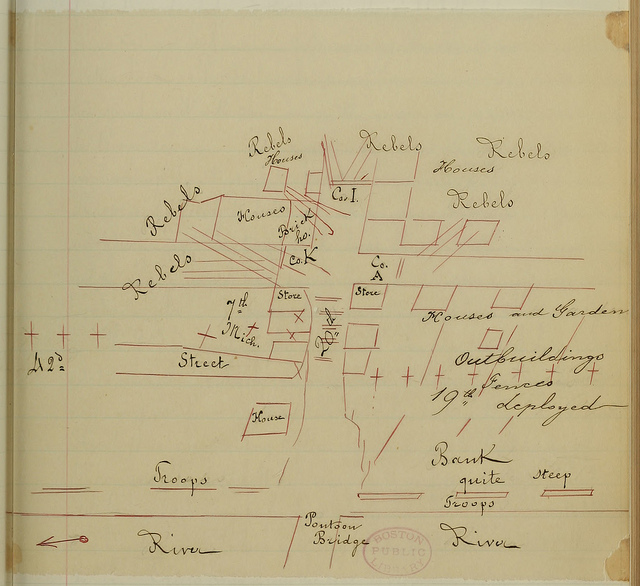

[Rough sketch map of Fredericksburg, accompanying letter from Henry Ropes to John C. Ropes, December 18, 1862], in Henry C. Ropes Letters, Vol. 3.

Rare Book Dept.

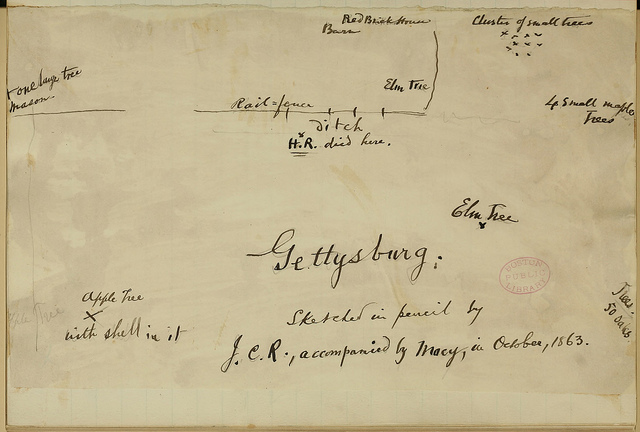

John C. Ropes

[Manuscript map showing where Henry Ropes died

at Gettysburg], in Henry C. Ropes

Letters, Vol. 3.

Rare Book Dept.

Invaluable insights about military life and detailed eyewitness accounts of individual battles can be gleaned from letters that soldiers sent to loved ones at home, such as those written by Boston resident Henry Ropes. He wrote extensive letters to his father and brother, often three and four pages in length. Occasionally he drew rough sketch maps to illustrate individual battles, including one of Fredericksburg, Virginia.

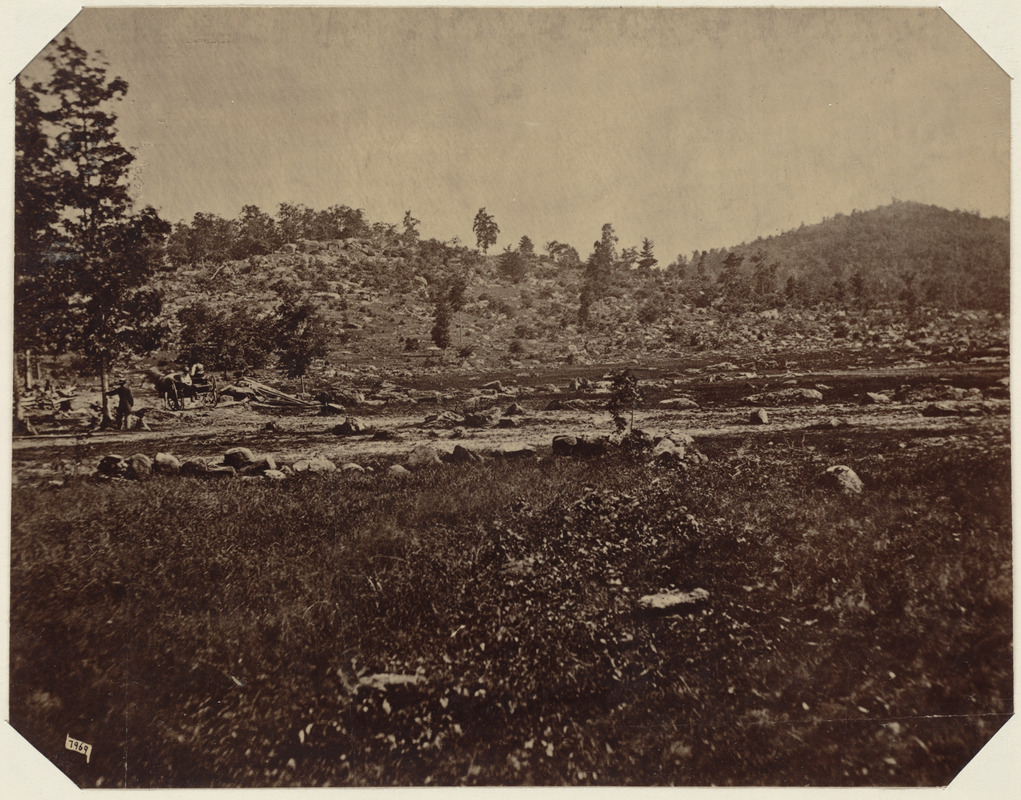

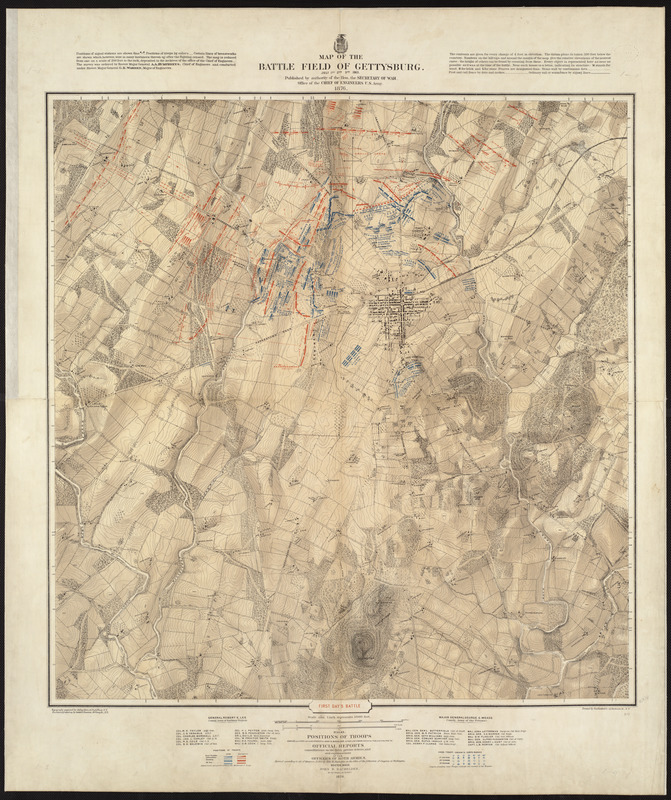

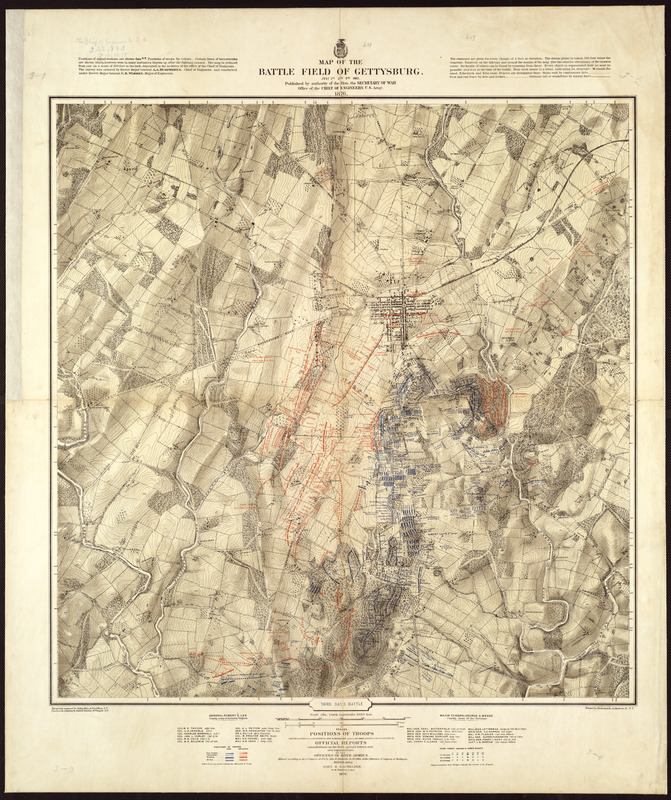

Ropes’ last letter was dated June 27, 1863, as his unit was marching toward Gettysburg. There are no more letters, since he was fatally wounded by friendly fire on the morning of the third day of the battle. The last item in the volume is a rough sketch map prepared in October 1863 by his brother John, noting “H.R. died here.“

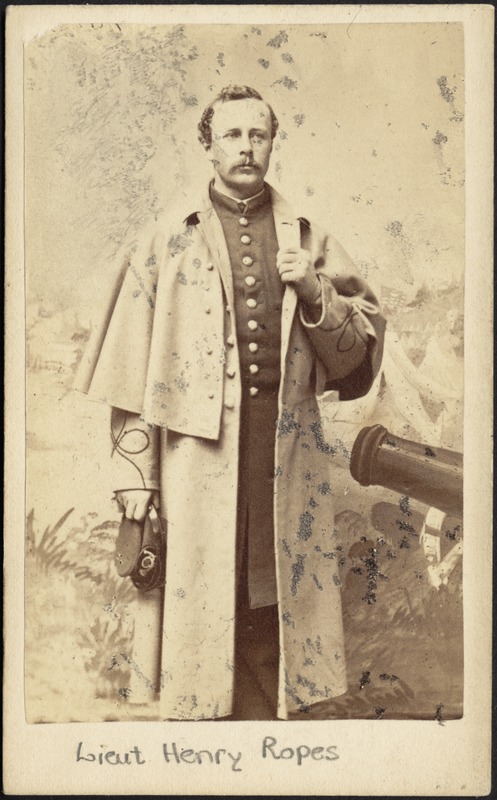

John Adams Whipple

Lt. Henry Ropes

Boston, [ca. 1862]

Print Dept.

Henry Ropes was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant with the 20th Massachusetts, November 25, 1862. He joined the regiment when they were headquartered at Camp Benton near Poolesville, Maryland.

Among the surviving artifacts from his short military career is a carte de visite, in which he is pictured in dress uniform, complete with cape and surrounded by artillery. The carte de visite, a popular item during the Civil War, was an inexpensive and simple means of obtaining photographs to send home.

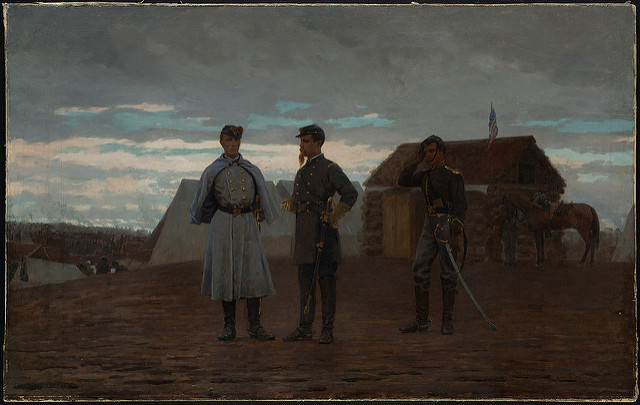

Winslow Homer

Officials at Camp Benton (Bartlett & Palfrey), Maryland, 1861

Oil painting, ca. 1881.

Rare Book Dept.

Among the true treasures of the Boston Public Library is an oil painting by artist Winslow Homer, entitled Officers at Camp Benton, Maryland, 1861. Commissioned twenty years after the event, it portrays Capt. William Bartlett and Lt. Col. Francis W. Palfrey of the 20th Massachusetts Volunteers at their camp near Poolesville, Maryland. Painted mostly from photographs at the request of a retired Colonel Palfrey, the image resembles an 1862 photograph, uniquely framed with epaulettes from his uniform. The photograph, which shows Palfrey and several other officers standing near a cabin at Antietam, may have served as the basis for this canvas. Although not executed while Homer was in situ as artist-correspondent, the subjects exhibit the same qualities of introspection and longing that are found in many of his wartime compositions.

[Col. Francis W. Palfrey's Civil War memorabilia, including a Book of Common Prayer which stopped a bullet; a photograph framed with epaulets of his headquarters at Antietam; and his sword]

Rare Books Dept.

A photograph, framed with epaulets, of officers standing in front of a cabin at Antietam, his sword, and a prayer book are several of the more unusual items found among the Civil War related artifacts and books saved and collected by Col. Francis W. Palfrey. The prayer book, which is inscribed with Palfrey’s initials, reportedly saved his life by stopping a bullet when he was wounded at Antietam.

Palfrey’s widow donated his collection to the Boston Public Library in 1892. These materials form the cornerstone of the 20th Regiment Collection, which continues to be funded by residue moneys contributed by the 20th Massachusetts Regiment Association for the installation of the Louis Saint-Gaudens lions on the landings of the Library’s grand stair case.

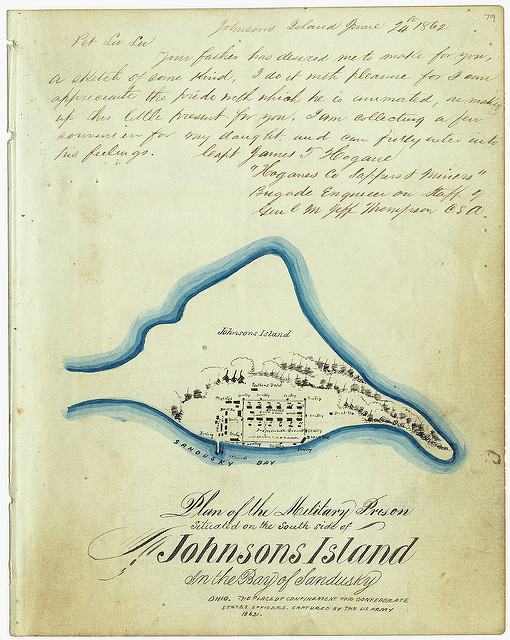

Capt. James T. Hogane

“Plan of the Military Prison, situated on the South Side of Johnson’s Island,” in [An Album of Autographs, etc. assembled by Joseph Barbaire, Capt., Company A, 1st Alabama, for his daughter LuLu Barbaire, while prisoner of war at Johnson’s Island, June 18, 1862]

Rare Book Dept.

A more unusual source for a manuscript map is an autograph book, which soldiers sometimes assembled as personal mementos of their fellow combatants. In this interesting example, there is a very finished drawing of the Military Prison at Johnsons Island, Lake Erie, where Confederate Officers were confined as prisoners of war.

This map was prepared by James Hogane, a Confederate engineer, at the request of his fellow officer, Joseph Barbaire, a captain with the 1st Alabama. The autograph book, which was intended as a gift for Barbaire's six-year old daughter LuLu, has an ornately decorated red leather cover. Barbaire’s fellow officers contributed autographs, short notes, poetry, several carte de visites, and two maps.

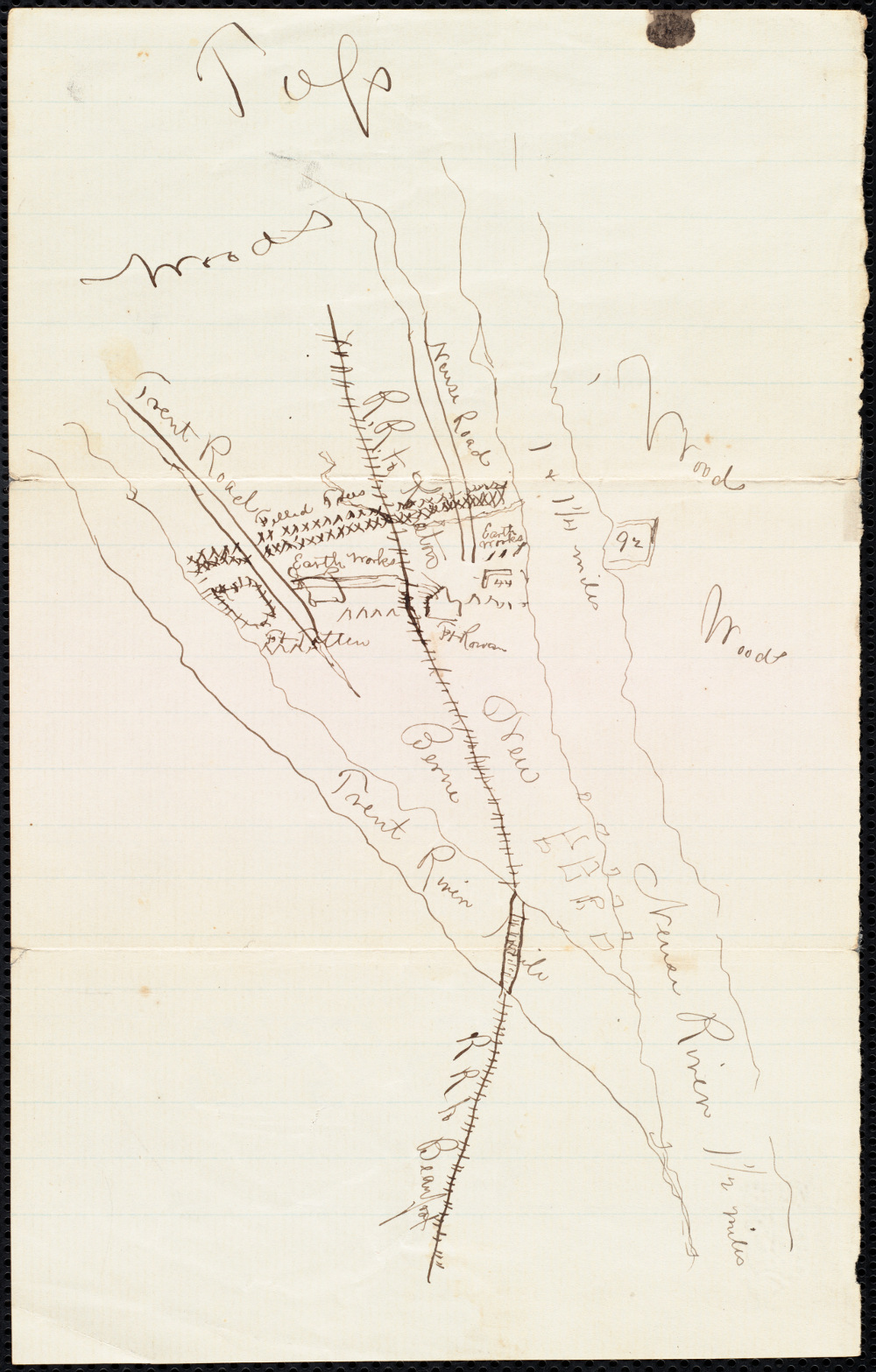

Joseph F. Dean

[Rough sketch map showing juncture of Trent and Neuse Rivers near New Bern, North Carolina, included in letter addressed to Mrs. H. C. Dean from Joseph F. Dean, March 22, 1863]

Rare Book Dept.

Among the most unique and interesting Civil War maps are relatively unknown manuscript maps drawn by individual soldiers during the war. Intended for a very limited and personal audience, such maps can be discovered in a variety of media, including daily journals and letters. For example, Joseph Dean with the 44th Massachusetts Regiment sent several letters to his mother in Boston. These letters, dated 1862 and 1863, were sent from Camp Stevenson near New Bern, North Carolina, where the regiment was stationed. Among the rough sketch maps that he drew is one showing the location of New Bern at the juncture of the Trent and Neuse Rivers. The town fell to Union forces March 14, 1862, and remained under Union control until the end of the war.

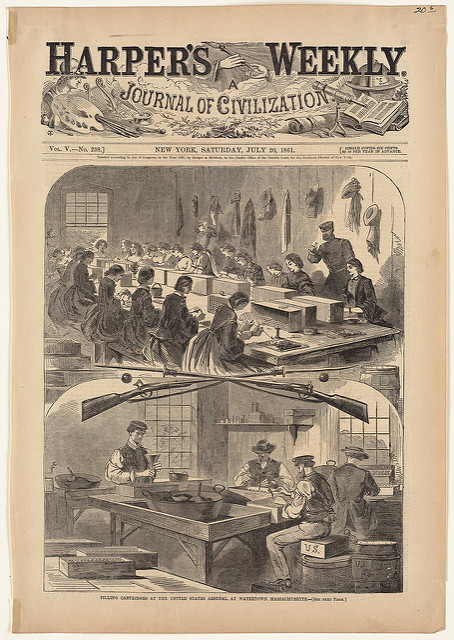

2C. Boston - Engine of War

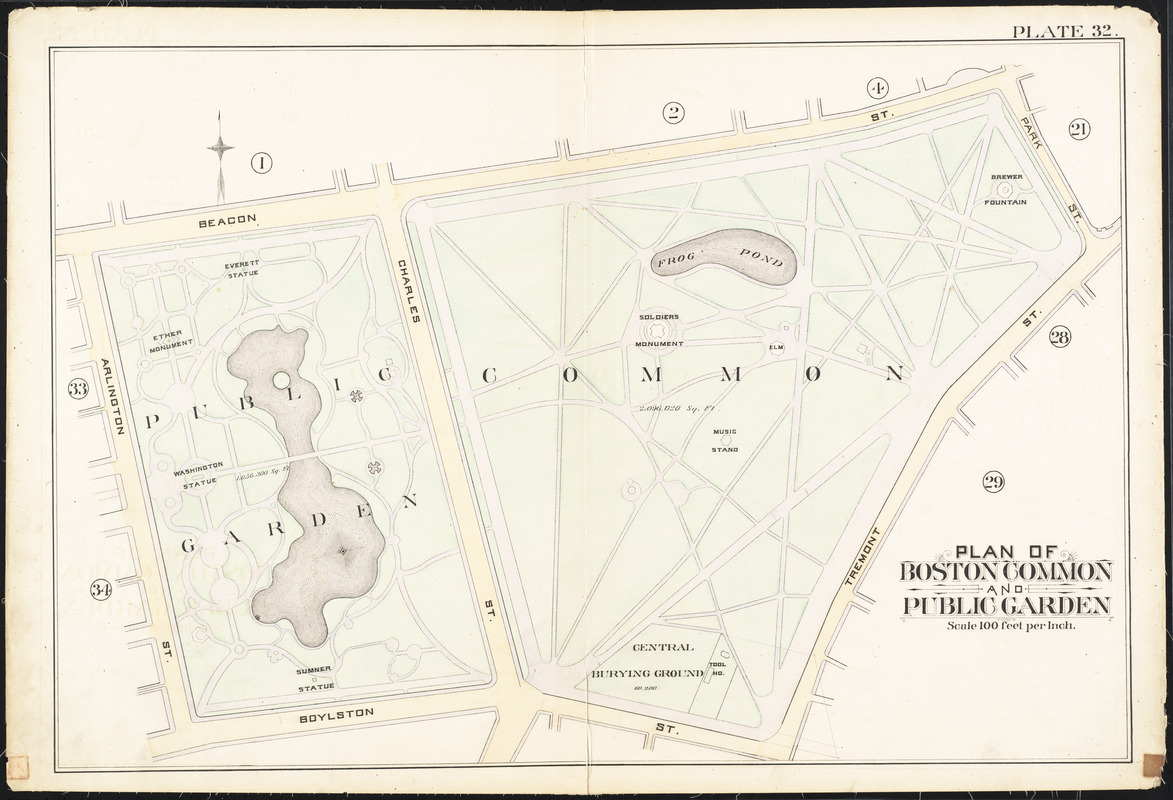

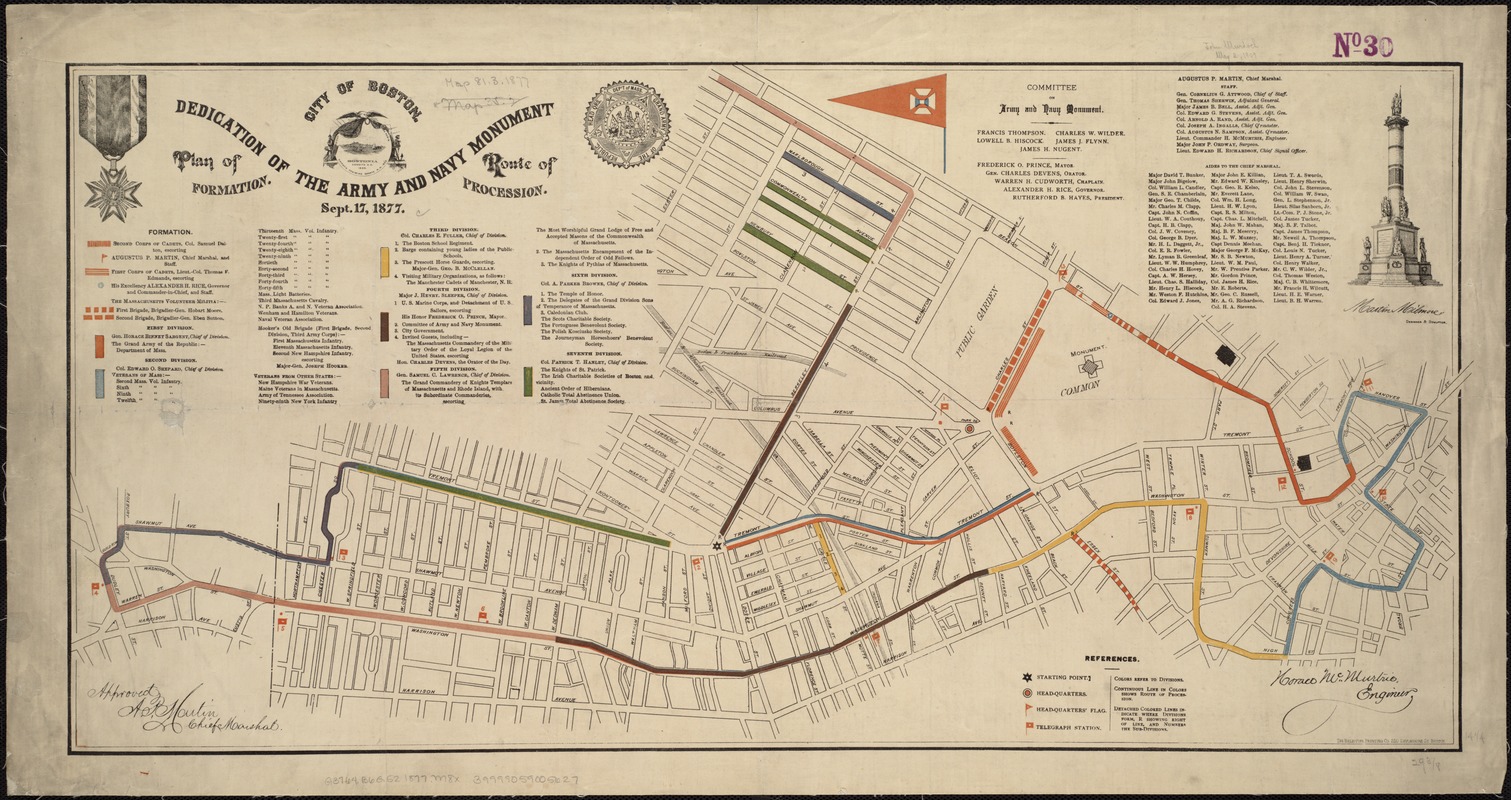

Despite its physical distance from the actual fighting, many activities integral to the war effort happened in the Boston area. Recruitment of soldiers occurred right on the Boston Common. Soldiers and sailors were trained at Camp Meigs, near suburban Readville, and Fort Warren on one of the harbor islands. Armaments were made at the Watertown and Charlestown arsenals. Through letters, gifts, and visits, wounded soldiers knew that those back home were doing everything possible to assist the Union cause.

Henry F. Walling

Map of the City of Boston and its Environs

New York, 1866.

Although no battles were fought in Boston, many people in the greater Boston area were heavily involved in war-related activities. The accompanying map portrays Boston and its neighboring communities at the end of the war. With a population of approximately 180,000, Boston proper was the largest city in New England, and the fifth largest in the United States.

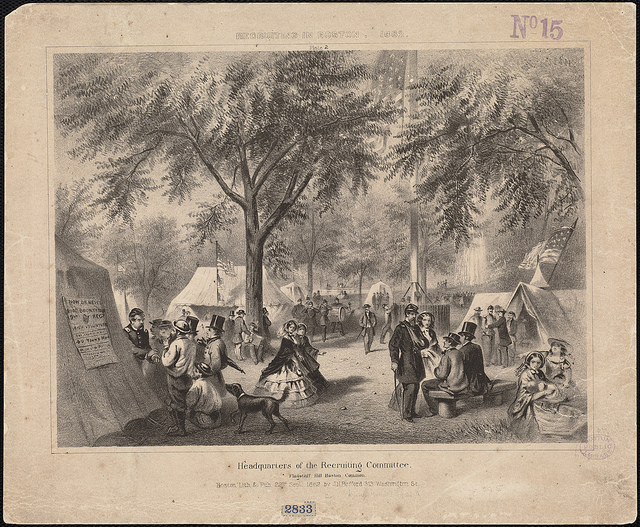

Headquarters of the Recruiting Committee, Flagstaff Hill, Boston Common

Boston: Bufford, 1862.

Print Dept.

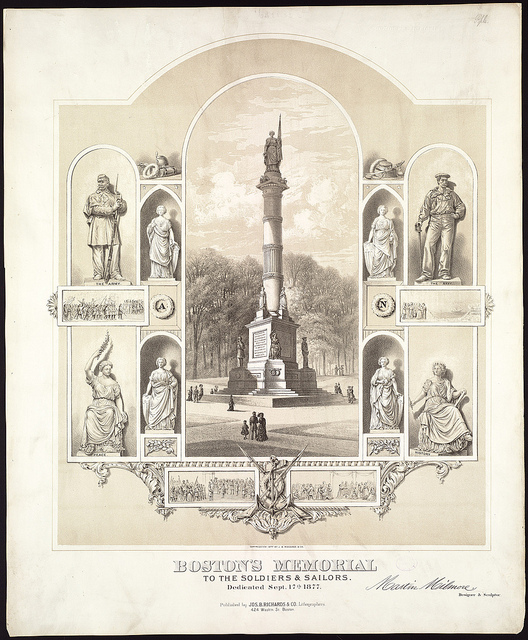

A crucial activity was the recruitment of young men to serve as soldiers. In 1862, President Lincoln called for 300,000 new volunteers to serve for three years; within a month he made another request for 300,000 more men to serve for nine months. Consequently, the recruiting committees were hard at work, as depicted in an 1862 print showing a recruiting station on Flag Staff Hill in Boston Common. In this illustration, Union soldiers converse with potential recruits as part of an extensive grass-roots recruiting effort. Massachusetts heard the President’s call and filled its quota. A monument dedicated to the soldiers and sailors of Massachusetts who perished in the Civil War now stands at this same site on the Boston Common.

Young women also played an important role in supporting the troops. As was customary, some ladies’ groups, such as those depicted in this 1861 photograph, made flags for local volunteer regiments. These Roxbury ladies presented their creation with great ceremony and fanfare to the city’s first company of volunteers in April 1861. Their presentation was recorded in the Roxbury City Gazette, which included the Mayor’s introductory remarks: “We are assembled on an interesting occasion to witness the presentation by the young ladies of Roxbury, of a banner to a company of our brave citizens about to step forward manfully in defense of the noblest government ever devised by human wisdom, and which is now endangered by the acts of rebels and traitors.“

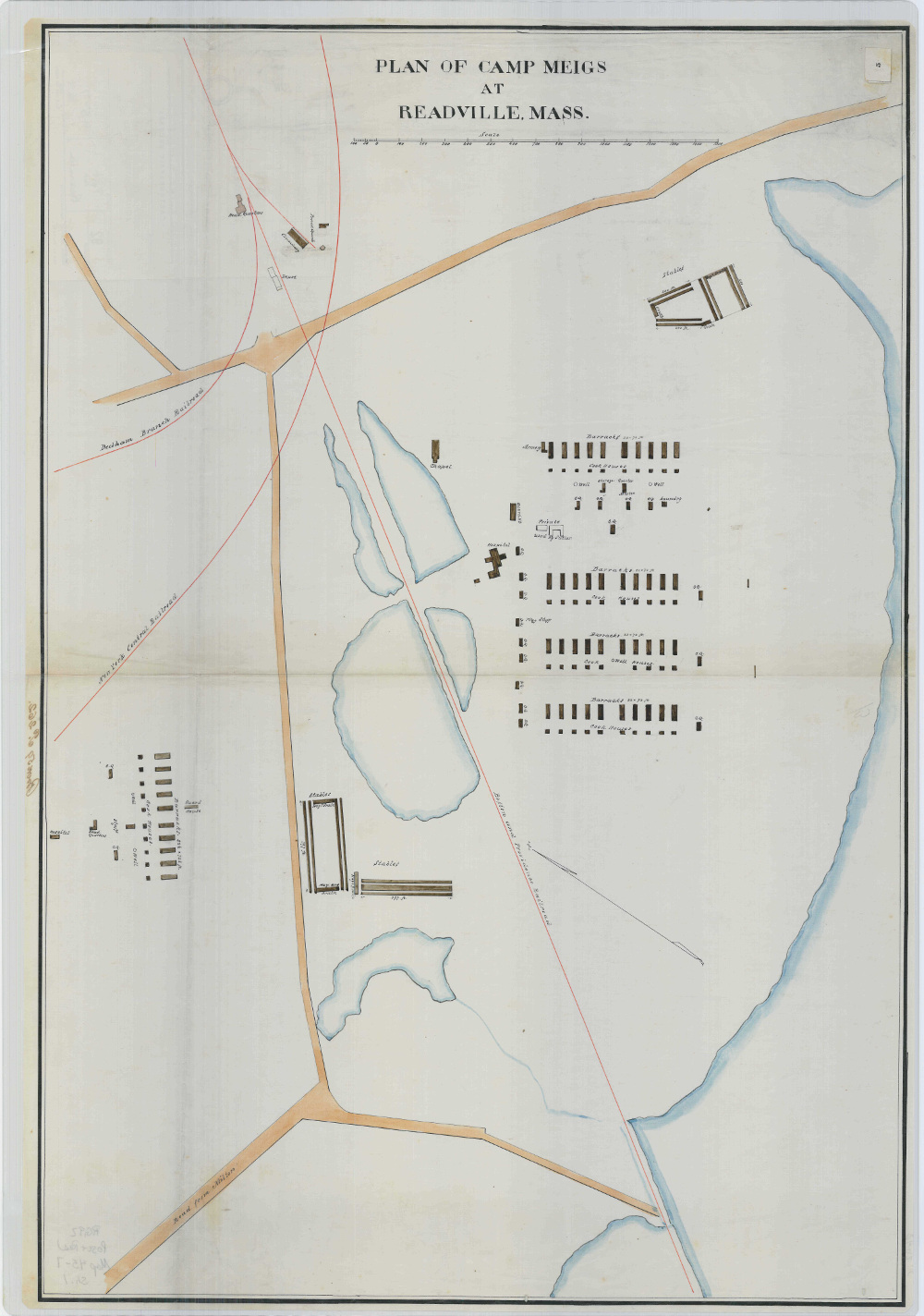

U.S. Army, Office of Quartermaster General

Plan of Camp Meigs at Readville, Mass.

Manuscript map, n.d.

Reproduction courtesy National Archives and Records Administration.

A number of Federal government facilities located in the Boston area were devoted to war-related activities. Among these was Camp Meigs, an army training center near Readville, now part of Hyde Park. Constructed by the Quartermaster General’s Office as a temporary facility, numerous Massachusetts regiments trained here before being deployed to the battle front. One of these units was the Massachusetts 54th led by Col. Robert Shaw, the first black regiment enlisted by any state during the war. The camp is illustrated with a ground plan prepared during the war showing the location of barracks, cook houses, and stables. It was named for Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs, Quartermaster General of the U.S. Army, who later designed the Pension Building in Washington, DC.

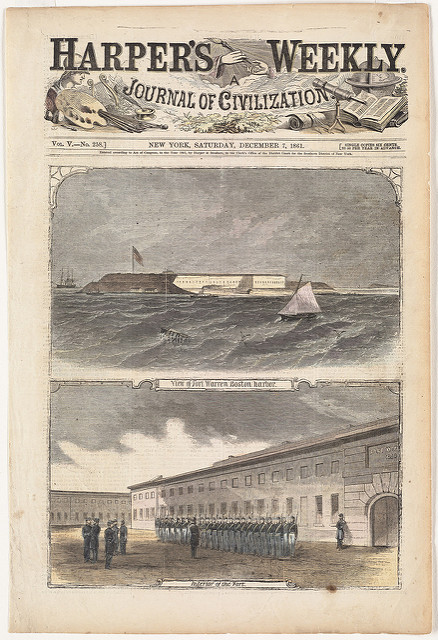

“View of Fort Warren, Boston Harbor” and “Interior of Fort,” from Harper's Weekly

December 7, 1861.

Print Dept.