Introduction

Boston boasts some of the nation’s most recognizable and cherished green spaces, from Boston Common, to the Emerald Necklace, to hundreds of neighborhood parks, playgrounds, tot lots, community gardens, playing fields, cemeteries, and urban wilds. In this exhibition, you will learn how the country’s oldest public park grew from a grazing pasture to an iconic recreational and social center, how 19th-century reformers came to view parks as environmental remedies for ill health, how innovative landscape architects fashioned green oases in the midst of a booming metropolis, and what the future holds for Boston’s open spaces. As you explore three centuries of open space in Boston, perhaps you will feel inspired to go outside and discover the green spaces in your own backyard.

Visit the exhibition at the Leventhal Map and Education Center

Forum Discussion: "Olmsted for the 21st Century: Creating Urban Change"

Recorded May 31, 2018

Forum Discussion: "Parks for All: How City Parks Address Inequity"

Recorded August 23, 2018

1. Growth and Green Space

John Bachmann (fl. 1849-1855)

"Boston, Bird’s-Eye View from the North"

Boston, 1877. Reproduction, 2011.

Hugely popular in the mid- to late 19th century, bird’s-eye views celebrated city growth by highlighting prominent landmarks, industrial innovation, and cutting-edge transportation. Here, artist John Bachmann viewed Boston from an imaginary vantage point hovering to the north of the city. This perspective allowed him to place public spaces such as the State House, Common, and Public Garden in the center of the frame, emphasizing their importance. Surrounded by tightly-packed buildings, tiny people and horse-drawn carriages dot these prominent green spaces. Just as they did in the 19th century, Boston’s parks offer breathing room in an ever-growing city.

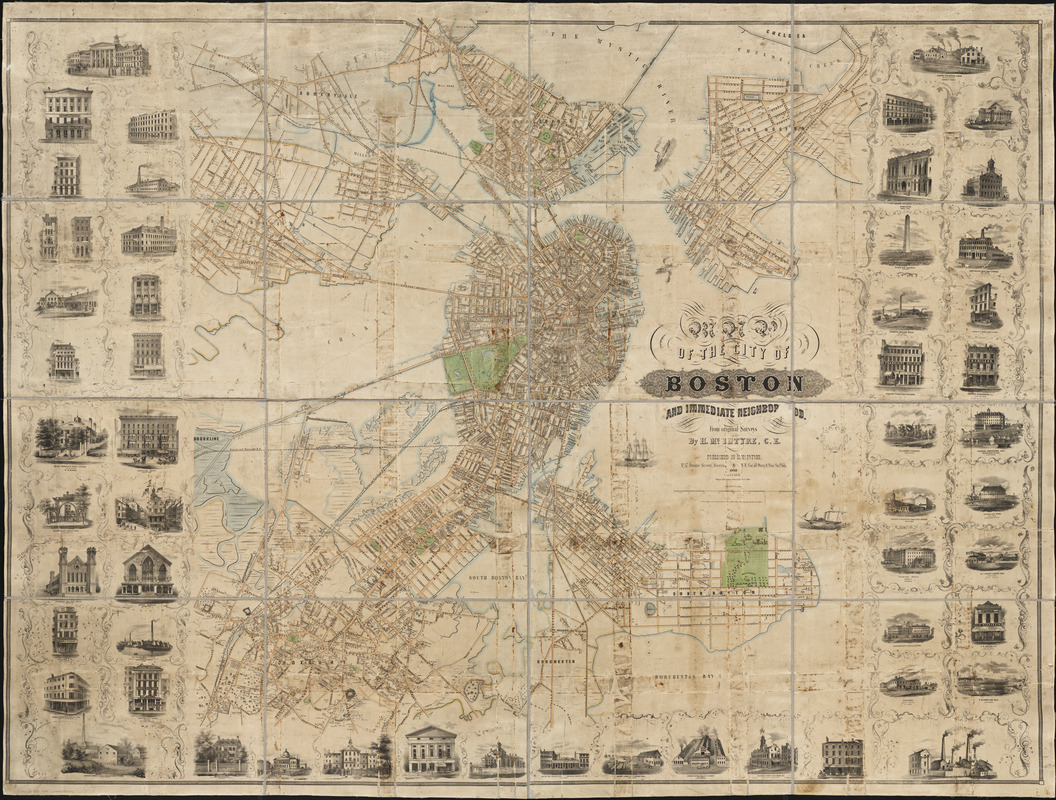

Henry McIntyre

"Map of the City of Boston and Immediate Neighborhood"

Boston, 1852. Reproduction, 2018.

This remarkably detailed map points to Boston’s tremendous growth in the mid-19th century. The footprints, or outlines, of individual buildings highlight the prolific development of the city’s built environment, while the marginal vignettes showcase significant public, private, and commercial structures, emphasizing Boston’s prosperity. A handful of green spaces—notably the Boston Common, Public Garden, and a number of cemeteries—provide some respite in an increasingly crowded and polluted city. In the years following this map’s publication, Boston would come to embrace its green spaces as healthful oases in a bustling metropolis.

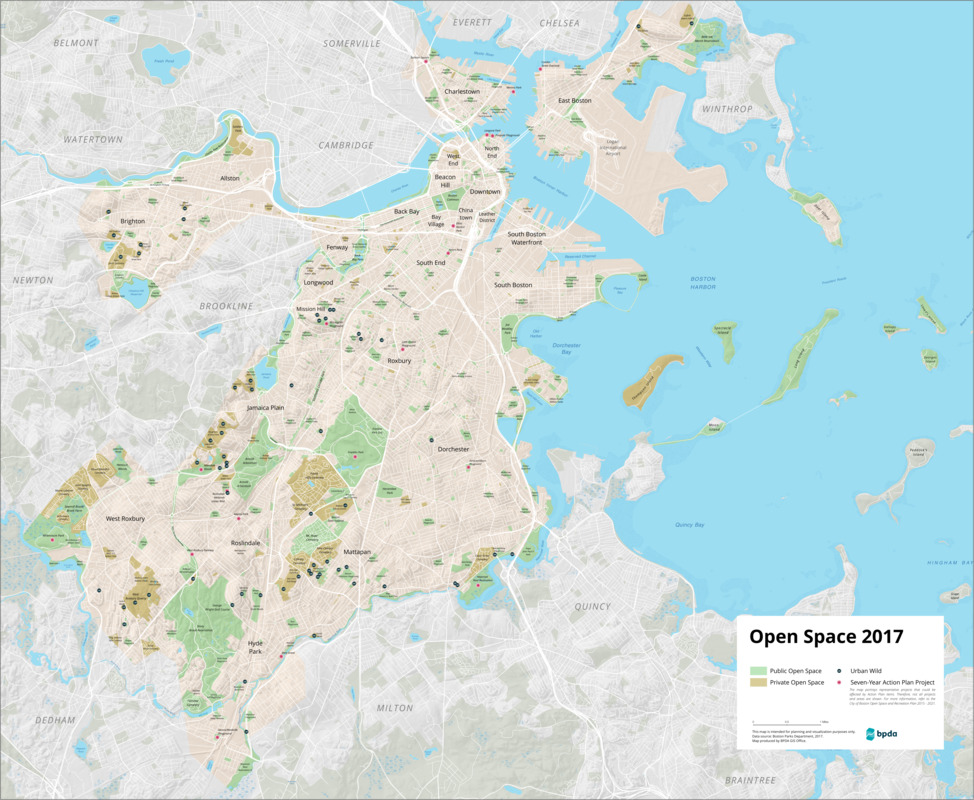

Boston Planning & Development Agency, Office of Digital Cartography and GIS

"Open Space 2017"

Boston, 2018.

Courtesy of the Boston Planning & Development Agency.

This map outlines public and private open spaces in Boston, as well as urban wilds, remnants of the original ecosystem that continue to flourish in pockets of the city. These wild areas are home to native plants and animals, and perform ecological services like retaining floodwater, producing oxygen, and filtering stormwater run-off. The map also features “Action Plan” items from the City of Boston’s "Open Space & Recreation Plan 2015–2021." Action items include developing new parks in neighborhoods like Brighton and Mattapan, improving natural habitats such as the Muddy River, maintaining public art and memorials, increasing tree canopy coverage throughout the city, and more.

2. Beyond Boston

Charles Eliot (1859-1897)

"Map of the Metropolitan District of Boston, Massachusetts: Showing the Existing Public Reservations and Such New Open Spaces as are Proposed by Charles Eliot…"

Boston, 1893.

This map was included in Charles Eliot’s report to the newly formed Metropolitan Park Commission (the predecessor to the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation) to encourage the preservation of green spaces within a ten-mile radius of Boston. Surging immigrant populations and frenzied development meant that open space in Boston was rapidly disappearing. As the Commission’s first landscape architect, Eliot declared that “crowded populations, if they would live in health and happiness, must have space for air, for light, for exercise, for rest, and for the enjoyment of that peaceful beauty of nature.” This topographic map depicts the open spaces he aimed to protect.

Geo. H. Walker & Co.

"Road Map of the Boston District Showing the Metropolitan Park System"

Boston, 1898.

Conservation of this piece was funded by Thomas L. Clemence in loving memory of Beverly E. Clemence.

By the late 19th century, the advent of the “safety” bicycle—so named because its two equally sized wheels, chain driver, and gears rendered it exponentially safer than the high-wheeled penny-farthing—ushered in a period of bicycle fever. One vocal bike fanatic was Sylvester Baxter, the Metropolitan Park Commission’s secretary, who advocated bicycling much as he did the use of parks; both promoted the physical, intellectual, social, and moral health of city-dwelling men and women. This map shows Boston and its Metropolitan Park System, with red-lined bicycle routes offering a means of exploring the nation’s first regional park system.

3. North of Boston

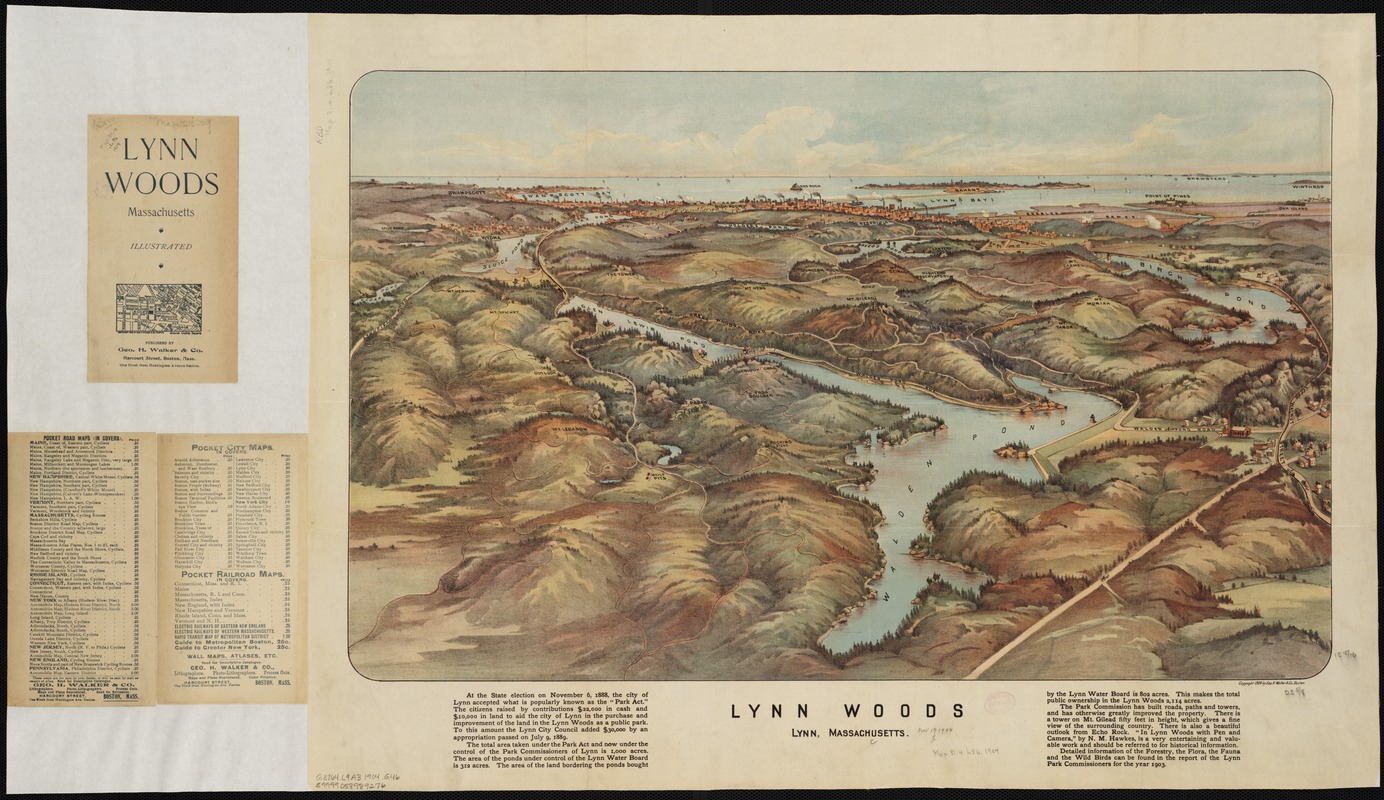

Geo. H. Walker & Co.

"Lynn Woods: Lynn, Massachusetts"

Boston, [ca. 1904].

In 1881, after the Lynn Water Department dammed a defunct millpond in Lynn Woods, a group of local recreationists formed a public trust to preserve the forest. The following year, the state legislature passed the Massachusetts Park Act, enabling any town in the Commonwealth to establish a park commission and acquire lands within its borders. Shortly thereafter, the Trustees of the Free Public Forest purchased parkland and hired Frederick Law Olmsted as a design consultant. Admiring Lynn Woods as a “real forest,” Charles Eliot hoped to incorporate the reservation into the Metropolitan Park System. This aerial view showcases the woods and ponds so admired by Eliot and the people of Lynn.

Massachusetts. Metropolitan Park Commission

"Middlesex Fells Reservation"

Boston, [1895].

Designed by the firm of Olmsted, OImsted, and Eliot, Middlesex Fells was among the four reservations that comprised the original Metropolitan Parks System, along with Beaver Brook, Stony Brook, and the Blue Hills. Charles Eliot used the Fells—which encompassed parts of Malden, Medford, Winchester, Stoneham, and Melrose—to demonstrate the need for a regional park system; no single community could protect the entire reservation. This topographic map illustrates the varied landscape that delighted Eliot, who wrote fondly of the reservation, “Here is a cliff and a cascade, here a pool, pond, or stream, here a surprising glimpse of a fragment of blue ocean...”

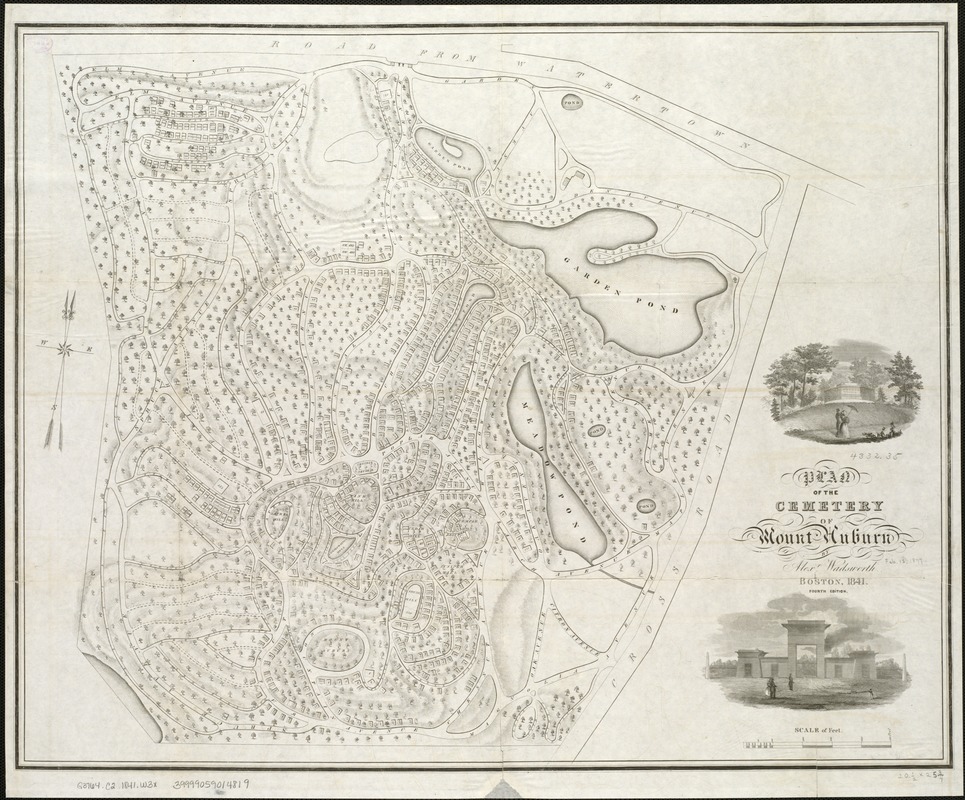

Alexander Wadsworth (1806-1898)

"Plan of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn"

Boston, 1841.

Mount Auburn Cemetery was consecrated in 1831 and is situated in Watertown and Cambridge, Massachusetts. Designed by Henry Dearborn with assistance from Alexander Wadsworth, Mount Auburn is celebrated as the first landscaped rural cemetery in the United States. Winding paths hug the cemetery’s natural hills and valleys, while dramatic plantings of shrubs and weeping trees—particularly the willow—were intended to encourage pensive strolls among dramatic arches, urns, “ruins,” decorative ponds, tombs, and burial plots. Later in the century, park advocates would point to these bucolic cemeteries to highlight the inadequacies of small urban parks, prompting the development of large, public open spaces within city limits.

4. South & East of Boston

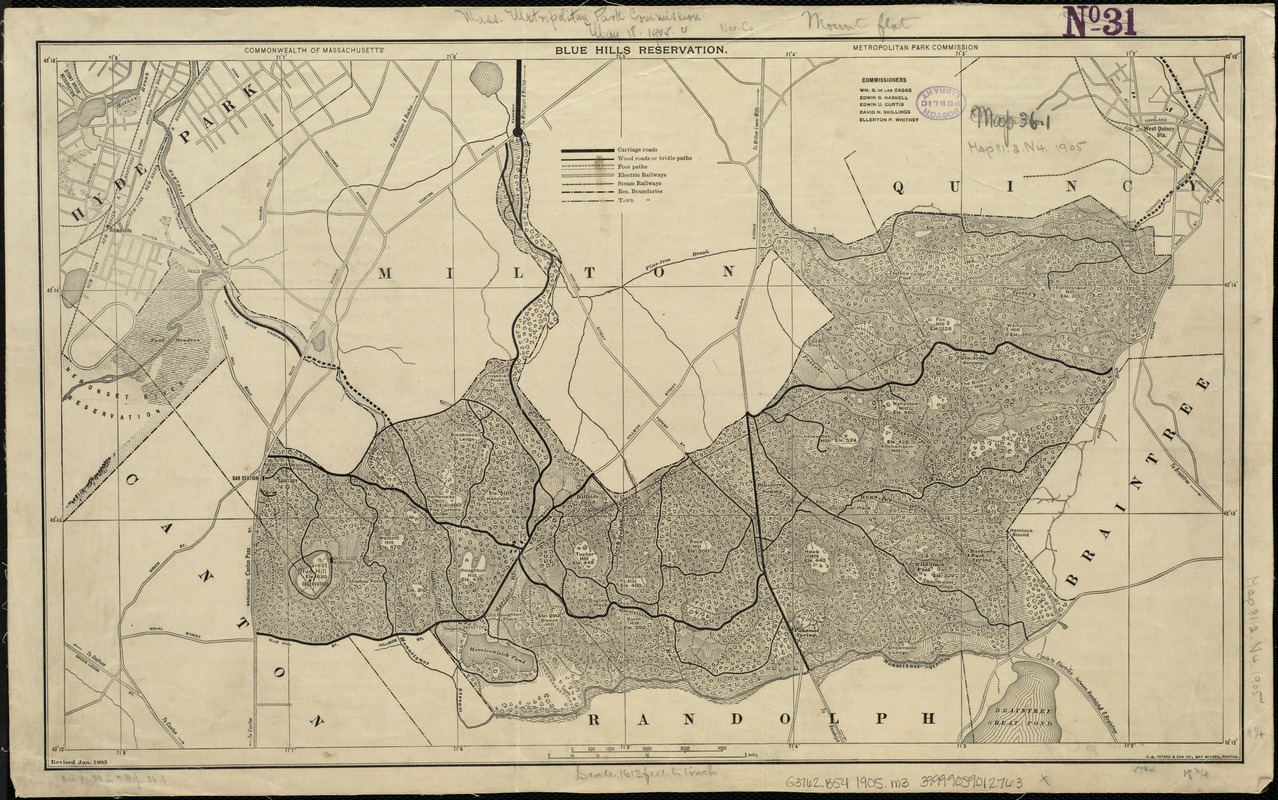

Massachusetts. Metropolitan Park Commission

"Blue Hills Reservation"

Boston, 1905.

Charles Eliot was instrumental in the acquisition of the Blue Hills Reservation by the Metropolitan Park Commission in 1893. He believed that the reservation’s “wildness” offered a counterpoint to Boston’s intentionally manicured urban parks, such as the Public Garden. When the fledgling Metropolitan Park Commission acquired the Blue Hills and three other reservations, Park Commissioner Herbert S. Carruth declared, “There will be no attempt made to beautify them. We shall not even own a lawn mower.” This map, created by the Park Commission in 1905, uses hachures to show the “bold” elevation changes that Eliot celebrated for their panoramic views.

John F. Murphy (Publisher)

"Bird's Eye View of Boston Harbor and South Shore to Provincetown Showing Steamboat Routes"

Boston, [1901].

Encompassing 34 islands and peninsulas, the Boston Harbor Islands comprise the largest recreational open space in eastern Massachusetts, and are all within 10 miles of downtown Boston. This bird’s-eye view, published at the turn of the 20th century for the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad and Fall River Line Steamers, promoted steamboats as a means of conveyance to the Harbor Islands. One contemporary writer noted with delight the islands’ increasing popularity: “Many beautiful steamboats traverse the harbor in every direction, touching at the principal islands and beaches, and carrying crowds of pleasure-seekers every pleasant day.”

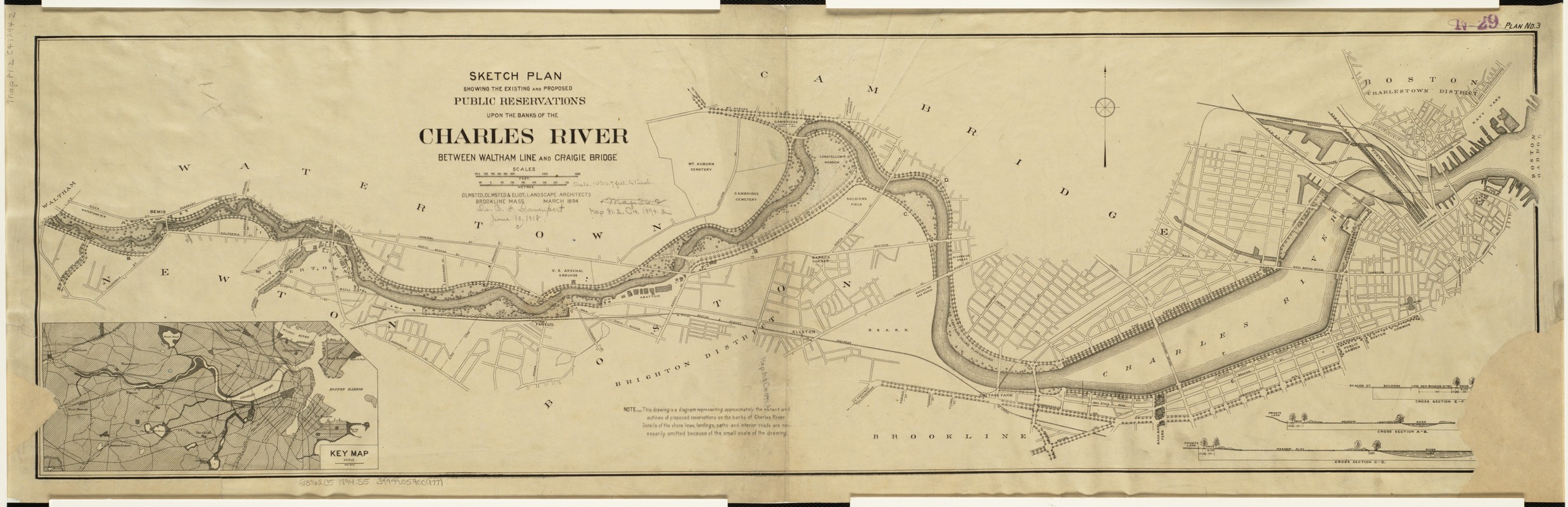

5. Charles River

Olmsted, Olmsted, and Eliot

"Sketch Plan Showing the Existing and Proposed Public Reservations upon the Banks of the Charles between Waltham Line and Craigie Bridge"

Boston, 1894.

The Charles River was once a tidal estuary. In the 19th century, its basin was dammed for mills and encircled by factories, prisons, and slaughterhouses, all of which polluted the slow-moving river. By the 1890s, local residents demanded a change, and in 1893 the newly created Metropolitan Park Commission and the State Board of Health tasked the firm of Olmsted, Olmsted, and Eliot with improving the river. This map reflects Charles Eliot’s vision of tree-lined promenades, playgrounds, gymnasia, and performance spaces. The Charles River Dam, completed in 1908, made Eliot’s dream a reality, and transformed the stinking tidal estuary into a scenic waterfront park.

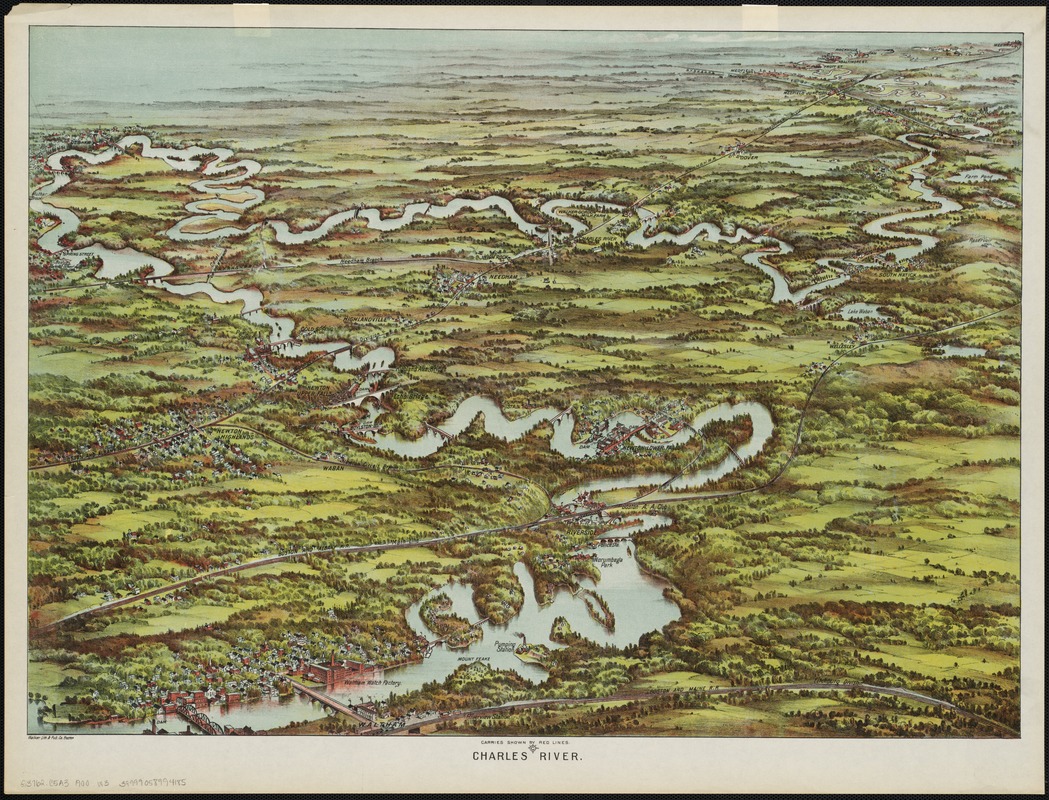

Walker Lith. & Pub. Co.

"Charles River: Carries Shown by Red Lines"

Boston, [1900?].

The Boston Marathon route runs 26 miles from Hopkinton to the Boston finish line; the meandering Charles River winds 80 miles between those same points, flowing through 23 communities before emptying into Boston Harbor. This bird’s-eye view, produced in the early 20th century, looks southwest from an imaginary vantage point above the industrial city of Waltham. The river snakes through the western suburbs, passing such landmarks as the Waltham Watch Factory, the industrial complex at Newton Lower Falls, and the now-defunct Norumbega Park. Rail lines crisscross the landscape, evidence of the growth of these river-adjacent towns.

6. The Common

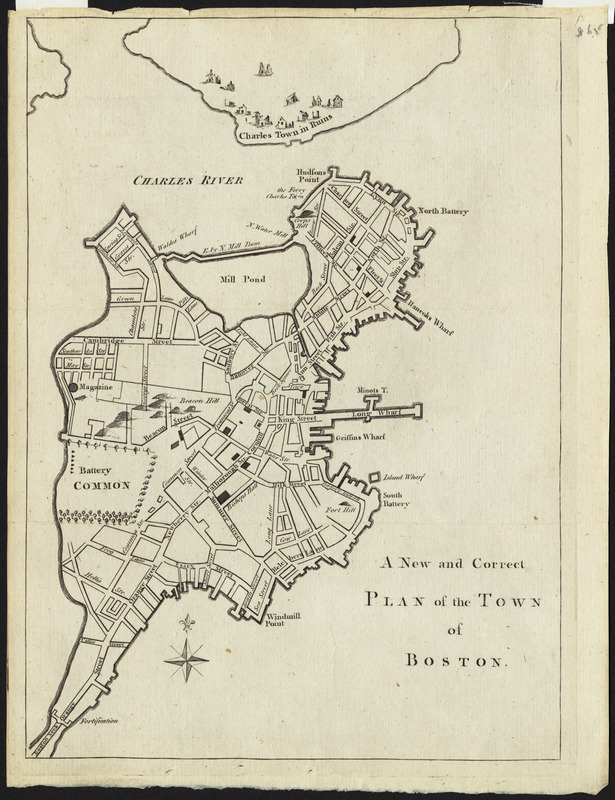

Thomas Hyde Page (1746-1821)

"A New and Correct Plan of the Town of Boston"

London, [1775].

In 1634, the colonists of Boston voted to tax each household six shillings for the purchase of William Blackstone’s farmland. As was English custom, the field was set aside as a public common, used by the community for military training, cattle grazing, recreation, and public punishment. During the winter of 1775, the Common served as an armed camp with an entrenched garrison of 1,700 British soldiers. Thomas Hyde Page, a military engineer who served as aide-de-camp to British General William Howe, prepared this map of Boston that same year, taking care to label the battery and tents dotting the Common.

John Rubens Smith (1775-1849)

"Beacon Street and the Common"

[ca. 1808]. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Print Department.

For 200 years, Bostonians used the Common as a pasture, military training ground, execution site, and pleasure ground, often simultaneously. By the time John Rubens Smith painted the Common in the early 19th century, the pasture was surrounded by houses and public buildings, including Charles Bulfinch’s new Massachusetts State House. As depicted here, people were content to share their promenade with cattle, at least for a time. Over the next few years, however, Boston’s wealthier inhabitants found this mingling of labor and leisure distasteful; in 1830, a city ordinance banned cows from the Common, leaving the working class to find new pastures, and transforming the pasture into a park.

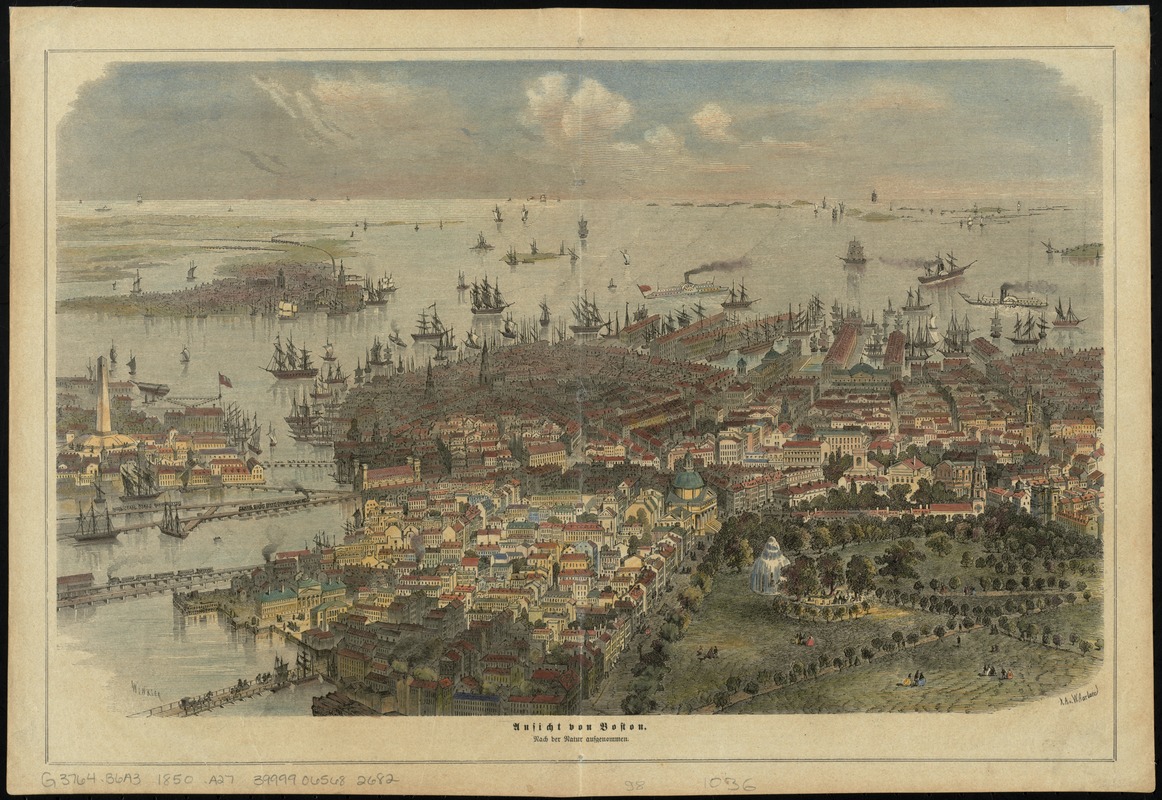

Johann Carl Wilhelm Aarland (1822-1906)

"Ausicht von Boston: Nach der Natur Aufgenommen"

[Leipzig], [1866].

Bird’s-eye views such as this one were immensely popular in the mid- to late 19th century. Often commissioned by city officials, these artistic views typically highlighted a city’s industrial growth, cutting-edge transportation facilities, and notable public spaces. Abutting the New State House, Boston Common features prominently in Wilhelm Aarland’s view, with park-goers scattered among tree-lined malls and the eye-catching Brewer Fountain; installed in 1868, the fountain was the first piece of public art featured on the Common. Meanwhile, steamships, fishing vessels, carriages, and trains converge upon a bustling city dotted with historic landmarks, commercial buildings, and church spires.

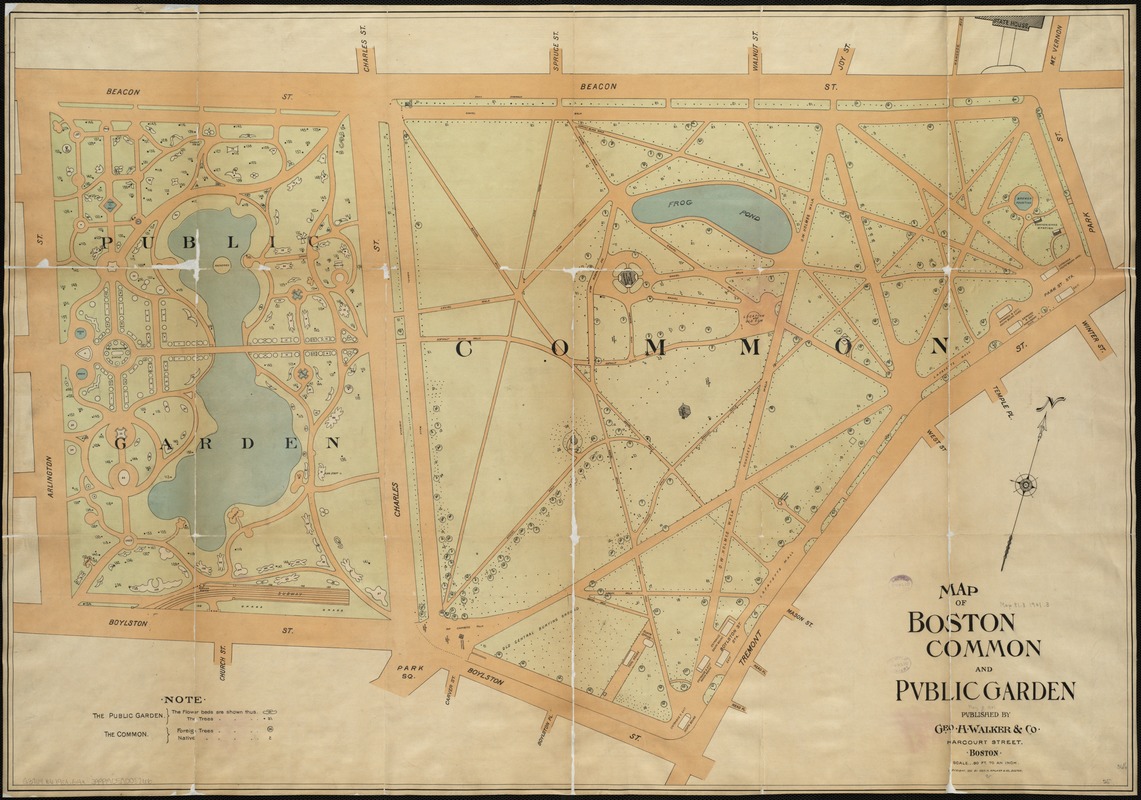

Geo. H. Walker & Co.

"Map of Boston Common and Public Garden"

Boston, [ca. 1901].

Whereas Boston Common was established on existing dry ground, the Public Garden was created between 1838 and 1860 on made land upon what was originally a salt marsh. Designed by George Meacham in response to New York’s Central Park, the Garden features undulating pathways arranged to encourage leisurely strolls among the exotic plant life. As superintendent of Boston’s Common and Public Grounds, William Doogue envisioned America’s first public botanical park as “a pleasure ground to the mass of God’s people, without any distinction as to race, color, or condition.” This map includes the names and locations of the trees and lays out the arrangement of the tulips.

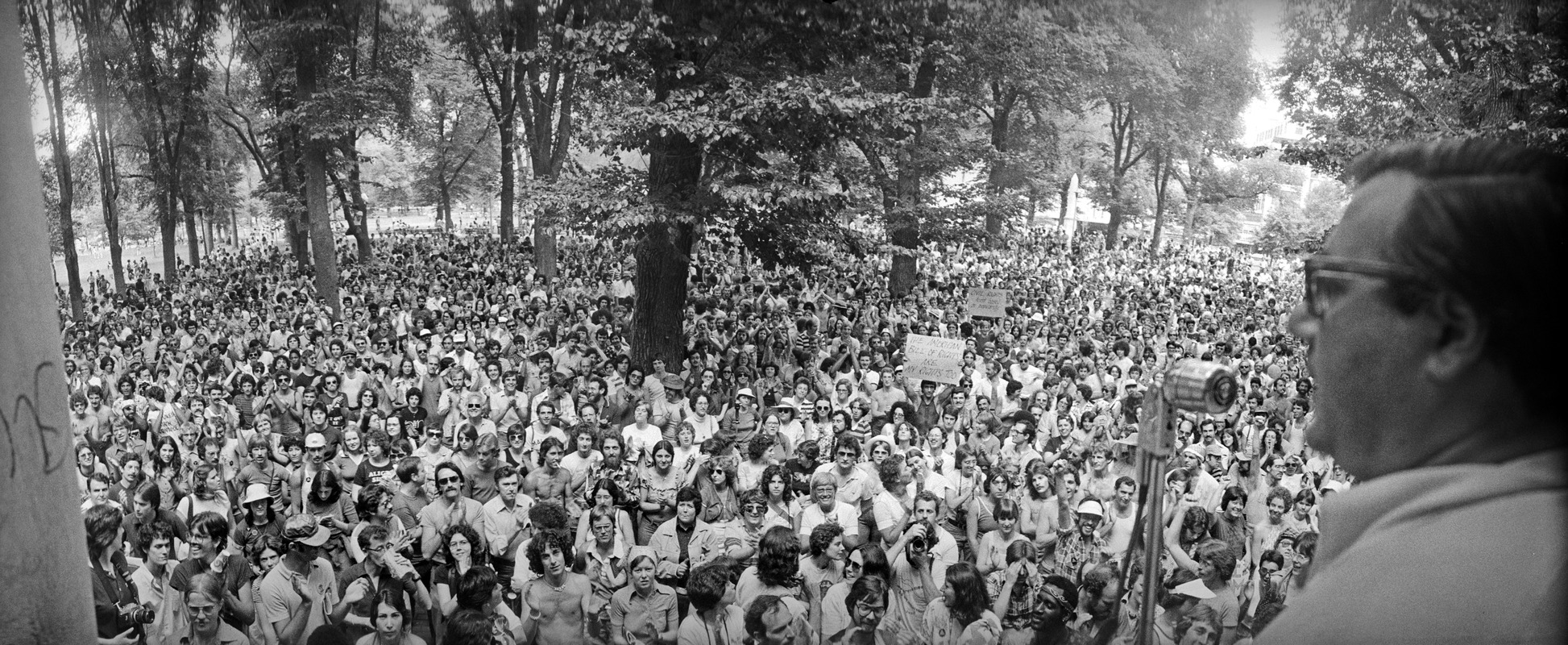

Spencer Grant (1944- )

"Anti-war Demonstration Aerials, Boston Common, 1970"

1970. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Print Department, Spencer Grant Collection.

Spencer Grant (1944- )

"Barney Frank Speaks at Gay Pride Rally at Parkman Bandstand in the Common, Boston"

[1977?]. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Print Department, Spencer Grant Collection.

From its inception in the 17th century to its present, Boston Common has been the staging ground for countless speeches, marches, and protests. A number of these were captured by local photographer Spencer Grant. The top photograph, taken in 1970, captures an estimated 60,000 to 100,000 people voicing their opposition to the ongoing Vietnam War. In 1977, after marching through the city in support of an anti-discrimination bill, protesters congregated on the Common to hear speakers, including Massachusetts State Representatives Elaine Noble and Barney Frank, shown in the lower photograph.

7. Breathing Places

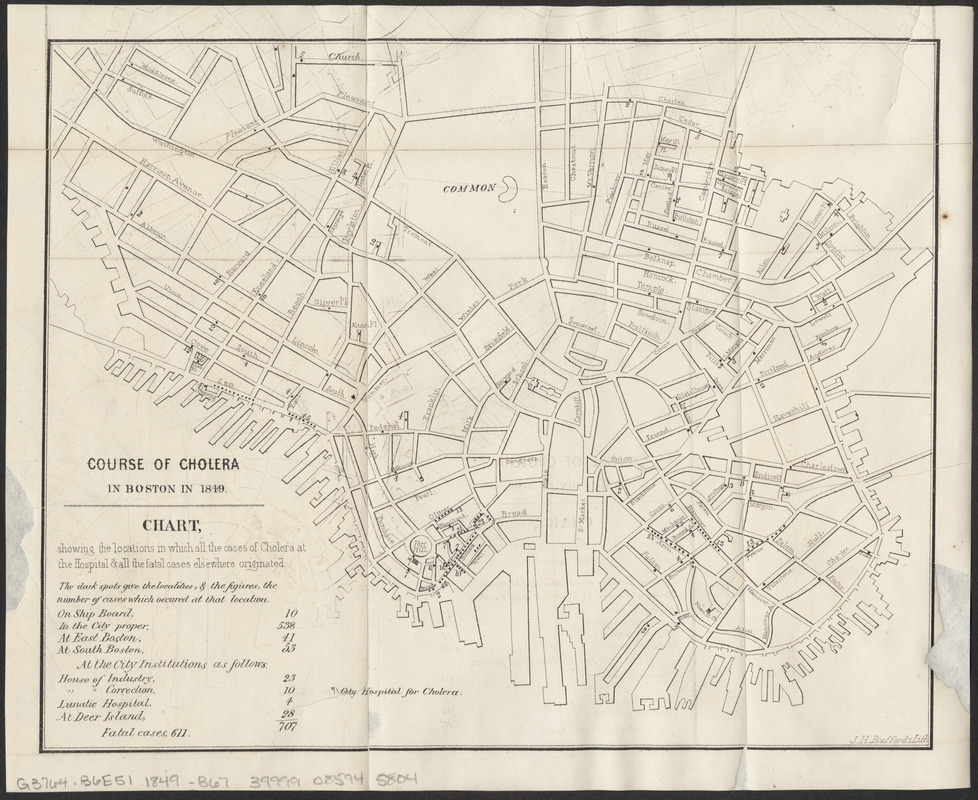

Boston (Mass.) Committee on Internal Health

"Course of Cholera in Boston in 1849"

[Boston, Mass.], 1866.

Conservation of this piece was funded by an anonymous donor.

Throughout much of the 19th century, it was widely believed that cholera and other diseases spread by way of miasma, or “bad air” emanating from decomposing organic waste. This map, first printed in a physicians’ report following the cholera outbreak of 1849, shows the origins of cases treated at the Cholera Hospital in Boston’s Fort Hill neighborhood. Situated in today’s Financial District, the Fort Hill tenements were occupied predominantly by Irish immigrants. In keeping with prevailing miasma theory and attitudes toward immigrants, the report blames the epidemic on overcrowding, poor ventilation, and the perceived intemperance and unsanitary behaviors of the victims.

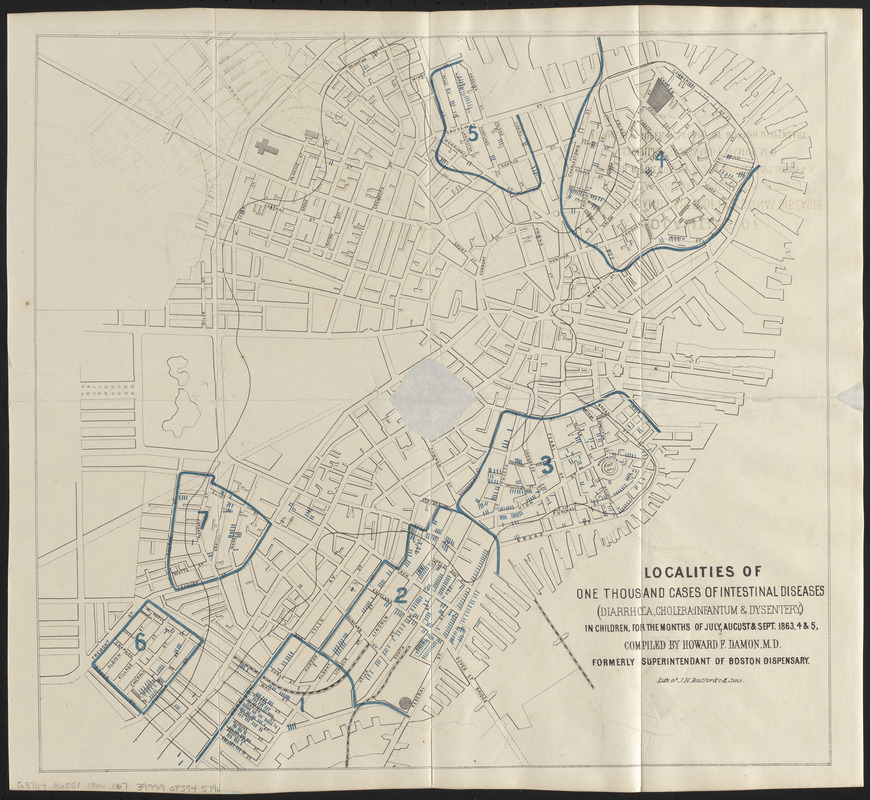

Howard F. Damon (1833-1884); Boston (Mass.) City Physician's Office

"Localities of One Thousand Cases of Intestinal Diseases (Diarrhea, Cholera Infantum & Dysentery) in Children, for the Months of July, August & Sept. 1863, 4 & 5"

[Boston, Mass.], 1866.

Conservation of this piece was funded by an anonymous donor.

In 1854, following a series of debilitating cholera outbreaks in London, Dr. John Snow studied patterns of deaths, plotting their locations on a map overlaid with the city’s water districts. He concluded that a contaminated well dispensing a waterborne “cholera poison” was to blame for the outbreak. Following his lead, Boston’s physicians, including Dr. Howard Damon, mapped the spread of diseases in an effort to understand the connection between health and environment. Shown here, Damon’s map pinpoints individual cases within clearly delineated “unhealthy districts” in Boston; his accompanying report concluded that these outbreaks correlated directly with “overcrowding and imperfect drainage.”

"Fort Hill Square"

[Boston], 1860. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Print Department, Boston Pictorial Archive.

Taken in 1860, this photograph offers a glimpse down a narrow street in Boston’s Fort Hill neighborhood, located in today’s Financial District. Population pressures and a lack of housing had transformed the area adjacent to the hill—partially visible on the right—into a warren of alleys packed with crowded tenements and shanties. Although the city acquired its first municipal water system in 1848, tenement landlords were disinclined to pay for plumbing. With hundreds of residents sharing a single public hydrant, neighborhoods like Fort Hill continued to use easily contaminated wells, and were among the hardest hit by the cholera outbreaks of 1849 and the 1860s.

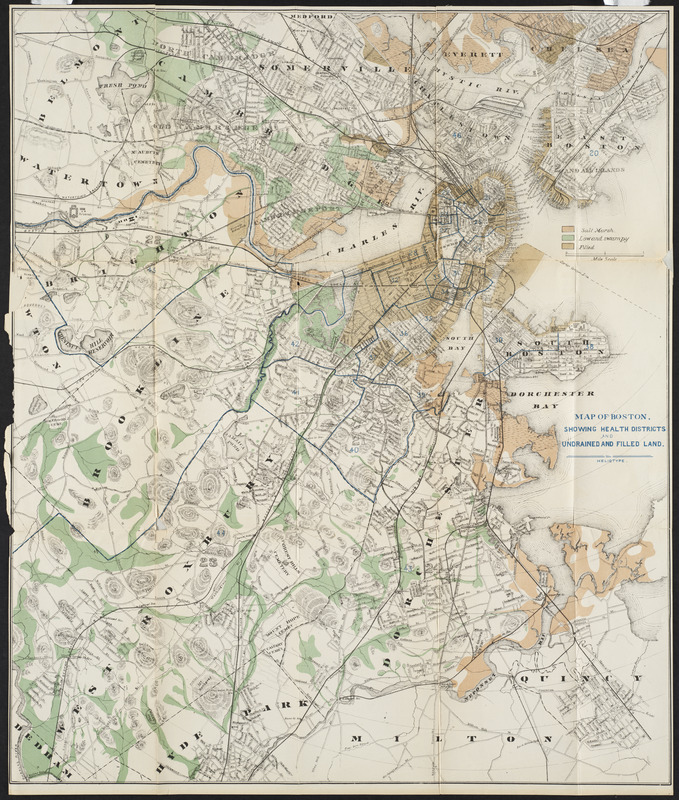

Heliotype Printing Co.

"Map of Boston: Showing Health Districts and Undrained and Filled Land"

Boston, [1870-1879].

Conservation of this piece was funded by an anonymous donor.

In 1874, the State Board of Health of Massachusetts divided the Commonwealth into “health districts,” areas assigned to physicians tasked with documenting the locations of prevalent diseases. This map denotes these health districts, along with the polluted marshlands and low-lying ground believed to spread diseases such as consumption, cholera, and malaria. If dark, damp, low land promoted illness, health reformers thought, then the opposite must hold true. In the years to come, Bostonians would increasingly seek out “breathing-places”: well-lit, dry, green spaces, where they might take in the fresh air for their health.

Boston (Mass.) Park Commissioners

"Map of Boston and a Part of Its Suburbs: Showing Public Recreation Grounds, Burial Grounds and Certain Other Public Properties Generally Free from Buildings"

Boston, 1886. Reproduction, 2018.

In 1885, landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted prepared a report detailing his plans for Franklin Park. This map, featured in the report, shows 186 open spaces either serving or available to serve as “recreation grounds or breathing-places.” While he recognized the value of parks in providing Bostonians with fresh air and active recreation, he wished to create an oasis devoted to quiet repose in a picturesque rural landscape. To Olmsted, cholera was not the only danger facing city dwellers; he believed that the overcrowding and artificiality of the built environment caused irritability, anxiety, and nervous tension that were remedied by passive recreation in rural scenery.

8. Back Bay

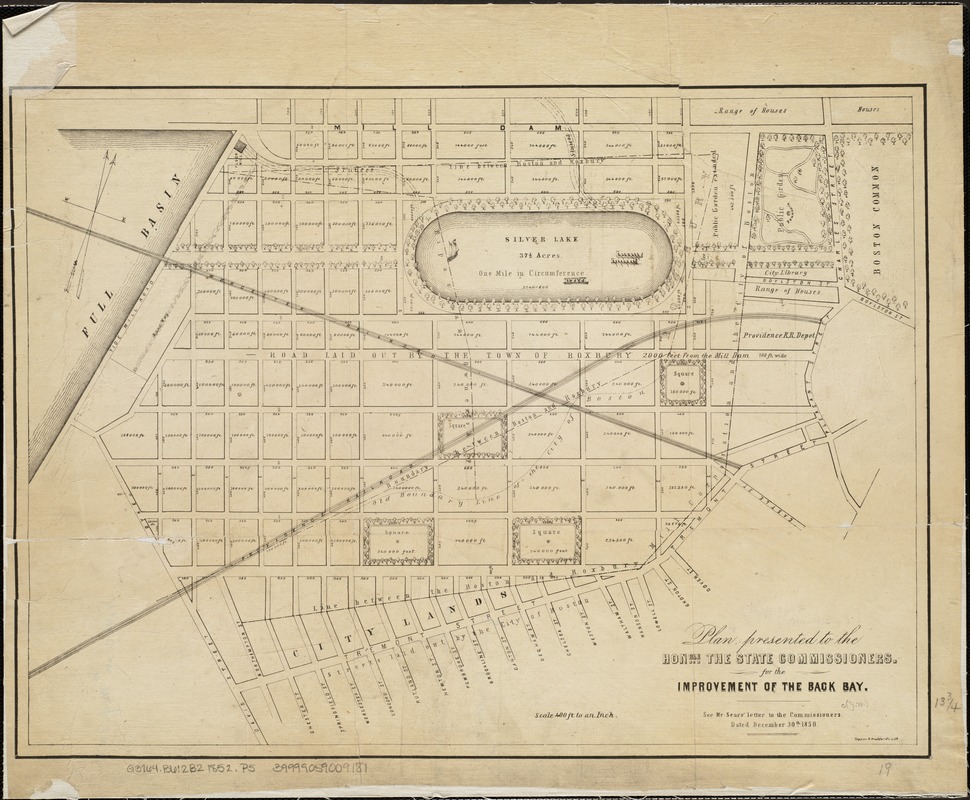

Tappan & Bradford (Publisher)

"Plan Presented to the Honble. the State Commissioners for the Improvement of the Back Bay"

Boston, [1852].

The Back Bay was once a marsh flat, but by the late 1840s, the severely polluted quagmire was considered a public health hazard, and officials had no choice but to act. The Commissioners on Boston Harbor and the Back Bay were tasked with devising a plan to fill in the flat. They met in 1852 and heard the proposals of a number of stakeholders, including David Sears; a version of his plan, shown here, features a 37 ½-acre Silver Lake, complete with a tree-lined promenade. The Commissioners ultimately rejected his proposal, and commenced the land reclamation project in 1858.

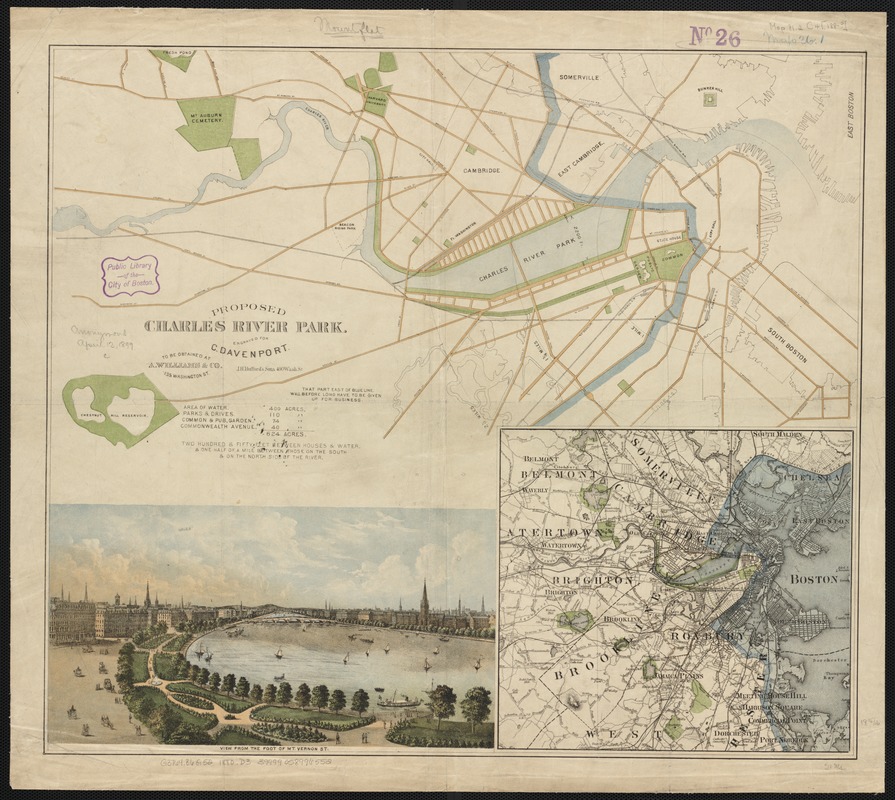

Charles Davenport

Proposed Charles River Park

Boston, [1880?].

By the late 19th century, Boston was a flourishing industrial city, but this success cost many workers their health, as they performed sedentary jobs in enclosed, dirty spaces. Cambridge manufacturer Charles Davenport proposed an esplanade running along the Charles River and parallel to Commonwealth Avenue. Shown here, this water park was intended to provide relief to city dwellers. The Charles River Esplanade that we recognize today, however, was yet to come: built in 1910 as part of the Charles River Dam construction, the Esplanade—known then as the Boston Embankment—would be expanded in the 1920s and 1930s by landscape designer Arthur Shurcliff.

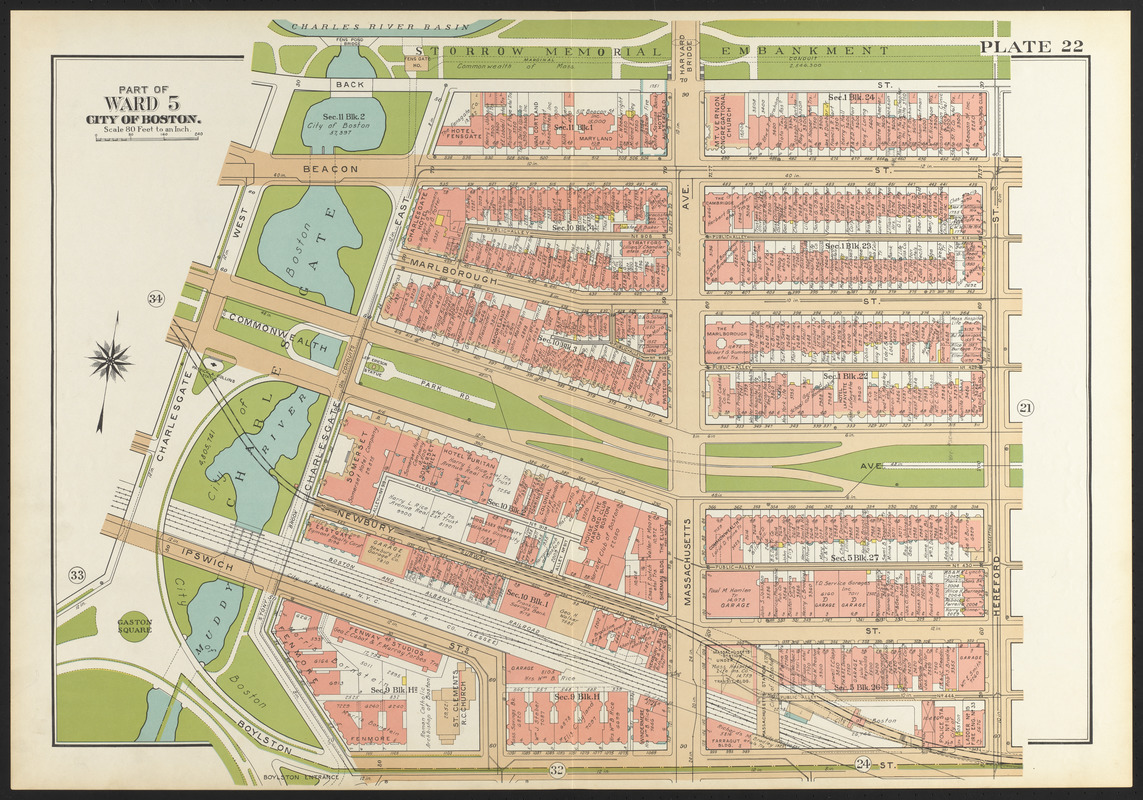

G.W. Bromley & Co.

“Part of Ward 5, City of Boston,” plate 22 from "Atlas of the City of Boston, Boston Proper and Back Bay"

Philadelphia, 1938. Reproduction, 2018.

Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted began his first Boston project in 1878, when the Boston Park Commissioners hired him to design the Back Bay Park (now the Fens), both as a sanitary improvement to the polluted and flood-prone Stony Brook and Muddy River, and as a public recreation ground. Charlesgate, as it appears here, was intended as the meeting place of the Fens and the Charles River, although the mid-20th century construction of Storrow Drive and the Bowker Overpass divided them for over 60 years. Today, the Department of Conservation and Recreation and the Department of Transportation are working on a Charlesgate Greenway, which will reconnect the Fens and the Charles River Basin.

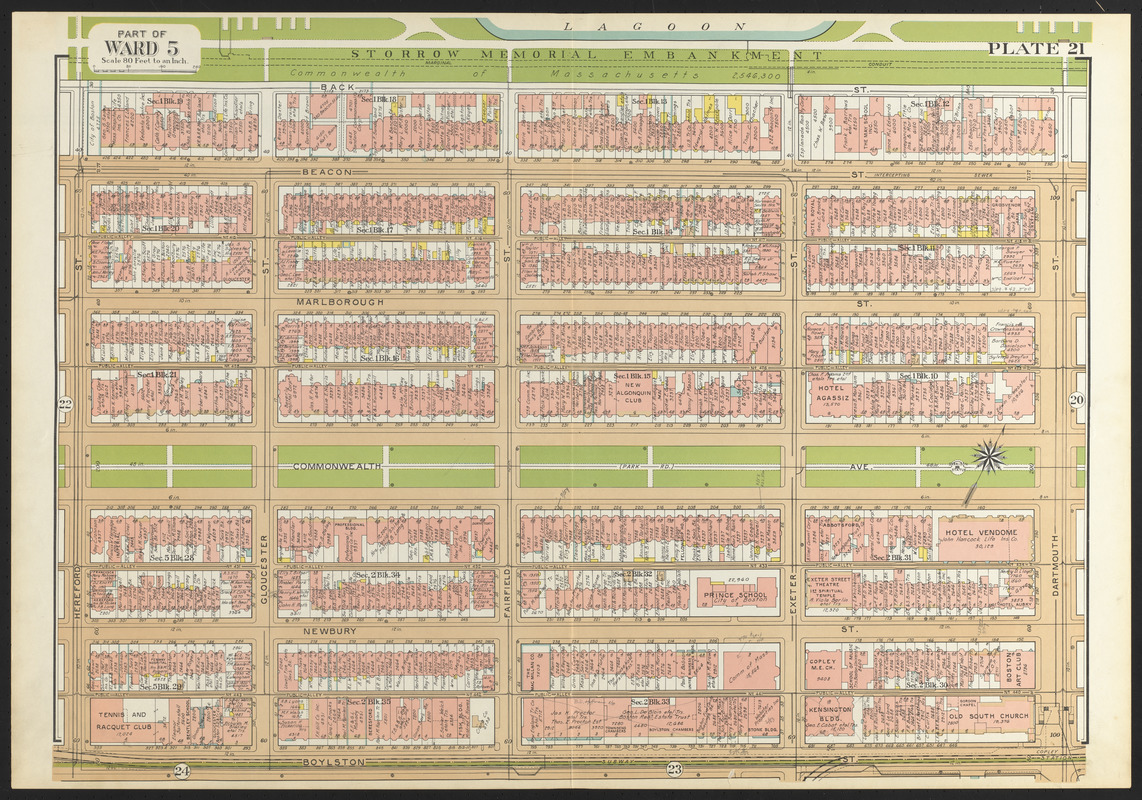

G.W. Bromley & Co.

“Part of Ward 5,” plate 21 from "Atlas of the City of Boston, Boston Proper and Back Bay"

Philadelphia, 1938. Reproduction, 2018.

Providing the link between the Public Garden and the Emerald Necklace, the Commonwealth Avenue Mall was Boston’s answer to majestic Parisian boulevards. Designed by architect Arthur Gilman, and incorporated into the park system in 1894, Commonwealth Avenue Mall was the centerpiece of the Back Bay’s widest and most manicured thoroughfare. The Mall extends from the Public Garden to present-day Massachusetts Avenue. To create a uniform and appealing space, strict building codes were enforced along the avenue. The result is a grand spatial corridor comprised of stately homes and deliberate green spaces.

9. Downtown

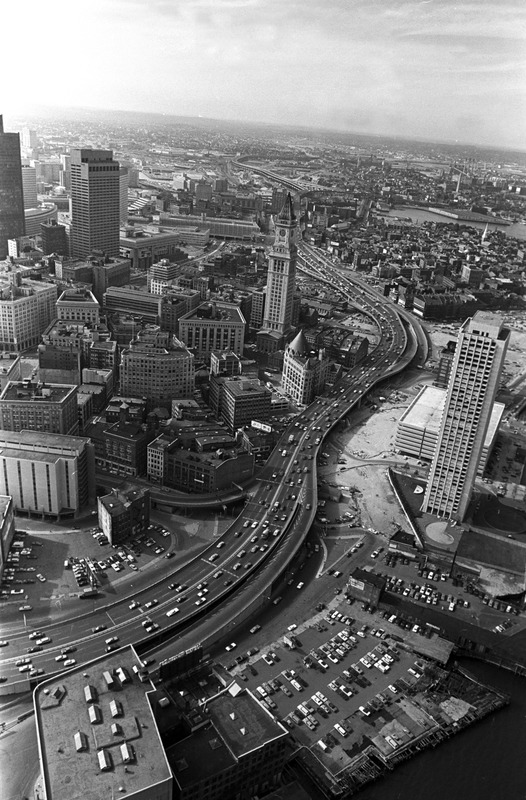

Spencer Grant (1944- )

"Central Artery and Downtown: Note Customs House & Harbor Towers, Downtown Boston"

[Boston], 1971. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Print Department, Spencer Grant Collection.

This aerial photograph, taken in 1971, shows the John F. Fitzgerald Expressway, more commonly known as the Central Artery. At the time of its construction in 1959, the six-lane elevated highway bisected the city and comfortably carried some 75,000 vehicles per day. By the 1990s, it supported upwards of 200,000 vehicles per day, making it one of the most notoriously congested highways in the country, and earning such dubious nicknames as “the Distressway” and “the other Green Monster.” The Central Artery/Tunnel Project, known locally as the Big Dig, would replace the elevated highway with an eight-to-ten-lane underground highway, taking 25 years to construct.

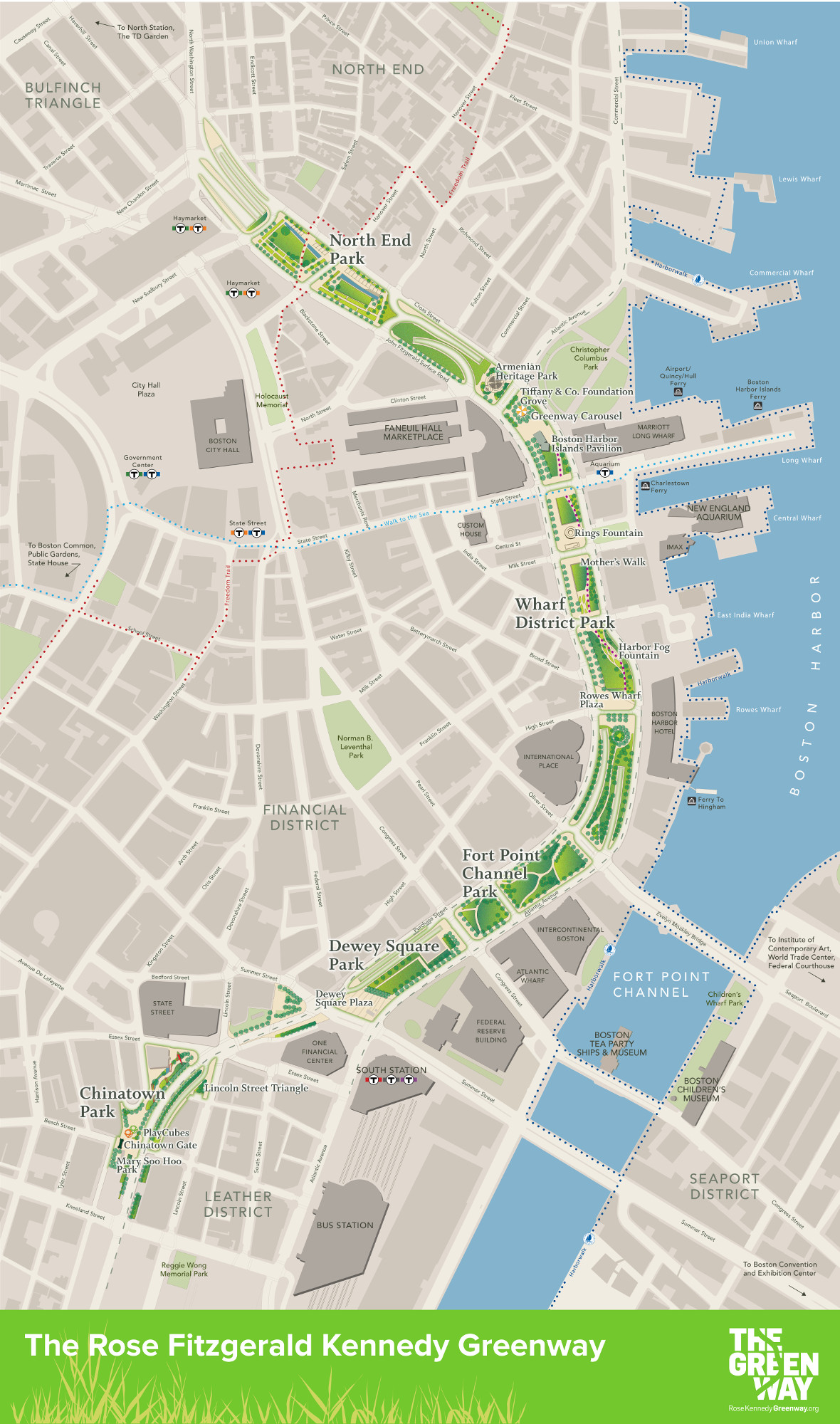

Rose Kennedy Greenway Conservancy

"The Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway"

Boston, 2017. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of the Rose Kennedy Greenway Conservancy.

As the “Big Dig” moved the Central Artery underground, community and political organizers seized the opportunity to enhance Boston’s new open spaces and reconnect neighborhoods. The Massachusetts Turnpike Authority (MTA), the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the City of Boston, and various civic groups collaborated to create the Rose Kennedy Greenway, a linear series of parks and gardens in the heart of Boston. Today, under the stewardship of the Rose Kennedy Greenway Conservancy, The Greenway park system connects the North End, Wharf District, Fort Point Channel, Dewey Square and Chinatown.

Kyle Klein

"[Aerial Photograph of the Rose Kennedy Greenway]"

Boston, 2017. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of Kyle Klein Photography.

Rose Kennedy Greenway Conservancy

"North End Park"

Boston, 2017. Reproduction, 2018.

Image courtesy of the Rose Kennedy Greenway Conservancy.

This aerial photograph, taken in 2017, shows the Rose Kennedy Greenway ribboning through the city, offering a marked contrast to the nearby black-and-white photograph of the elevated Central Artery taken 46 years prior. Lush gardens, fountains, tree-lined promenades, public art, food vendors, and a carousel have replaced the congested expressway, which now flows beneath the feet of park visitors. A second color photograph offers a “zoomed-in” view of Bostonians picnicking, reading, relaxing, and frolicking in the fountains in The Greenway’s North End Parks on a warm summer day in 2017.

Charles R. Parsons (1844-1918)

"Bird’s-Eye View of Boston, Showing the Burned District"

New York, 1872.

Gift of Bank of America.

Three weeks after the Great Fire of Boston, "Harper’s Weekly" published this bird’s-eye view outlining the extent of the burned district. The most devastating fire in Boston’s history, the Great Fire of 1872 obliterated more than 60 acres of the commercial district; businesses, homes, and churches were among the 776 buildings destroyed, and about 13 people lost their lives. Realizing that overcrowded lanes and poorly planned neighborhoods had propelled the spread of fire, the city widened streets, implemented new firefighting infrastructure, and cleared land to create Post Office Square.

Peter Vanderwarker

"Parking Garage Unit 3 (1954 - 1988)"

[ca. 1985 – 1987]. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of the Friends of Post Office Square.

Constructed in 1954, Parking Garage Unit 3 was a four-story garage that filled Post Office Square. In 1983, Boston developer and philanthropist Norman B. Leventhal formed the Friends of Post Office Square. Norman would later go on to establish the Norman B. Leventhal Map and Education Center at the Boston Public Library. At this time, however, his energies were focused on replacing the dilapidated “Unit 3” with a public green space that would be maintained and funded by an underground garage. This photograph was taken around the time that the Friends purchased the garage in 1987; demolition began the following year.

Ed Wonsek

"[Aerial 2 Sept 2012 at Dusk]"

[Boston], 2012. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of Halvorson Design Partnership.

In 1988, the Friends of Post Office Square demolished “Unit 3,” the deteriorating aboveground parking garage that dominated the Square since its construction in the 1950s. In its place, they constructed an underground garage with the 1.7-acre Norman B. Leventhal Park serving as a “green roof.” The city’s first privately financed park is supported both financially and structurally by the garage below, while trees, grassy plazas, garden trellis, and fountains offer some “breathing room” in the heart of Boston’s Financial District.

10. East Boston

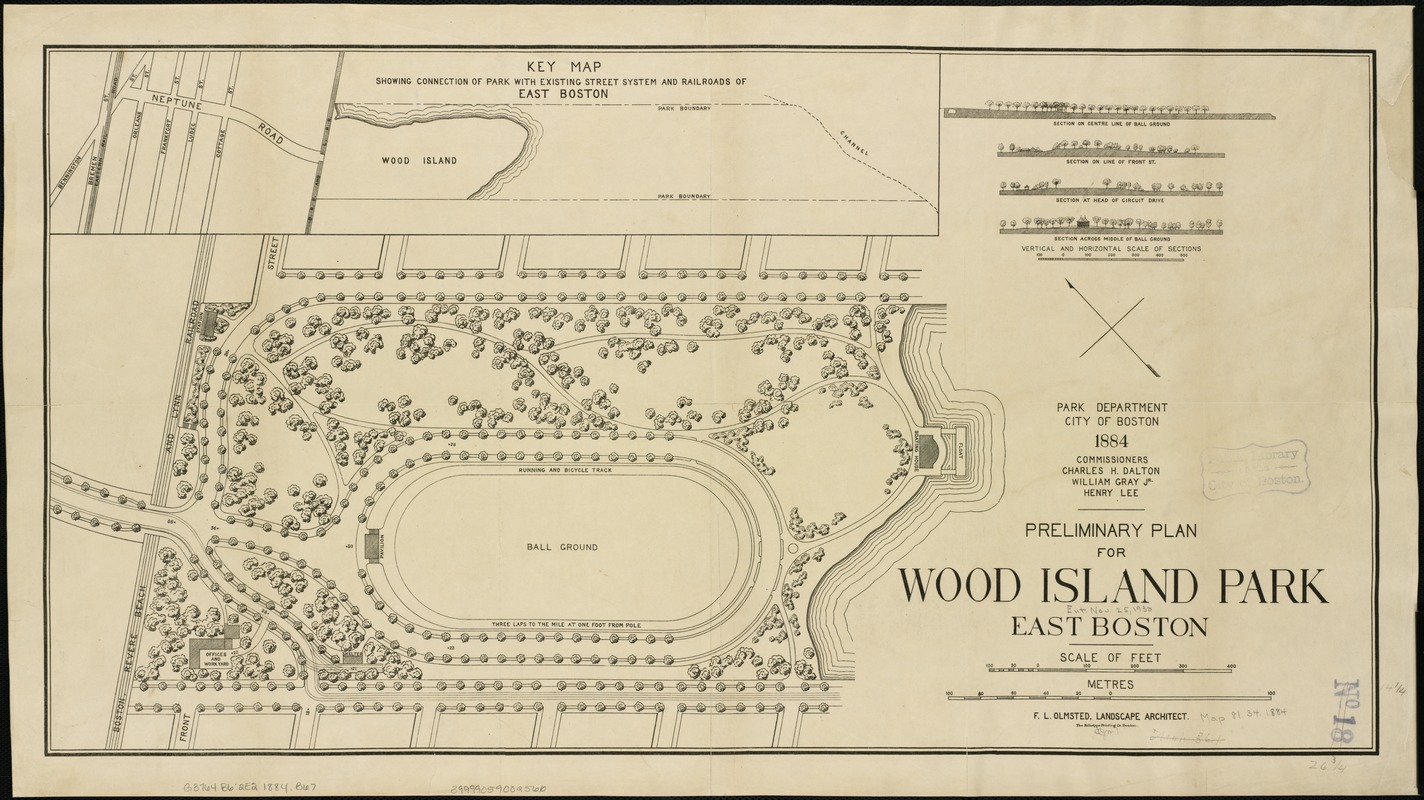

Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903)

"Preliminary Plan for Wood Island Park, East Boston"

Boston, [1884].

Frederick Law Olmsted’s celebrated Emerald Necklace often eclipses his five smaller, isolated parks in Boston, like Wood Island Park in East Boston. Though this plan shows a simple park featuring few walks and a playing field, Olmsted would transform Wood Island into his largest neighborhood park, with forty-six acres of public beach, picnic areas, tennis courts, outdoor gymnasiums for men and women, playgrounds, and several promenades. Despite its popularity, the park was razed for the expansion of Logan Airport in the mid-20th century, setting off decades of community activism and park advocacy.

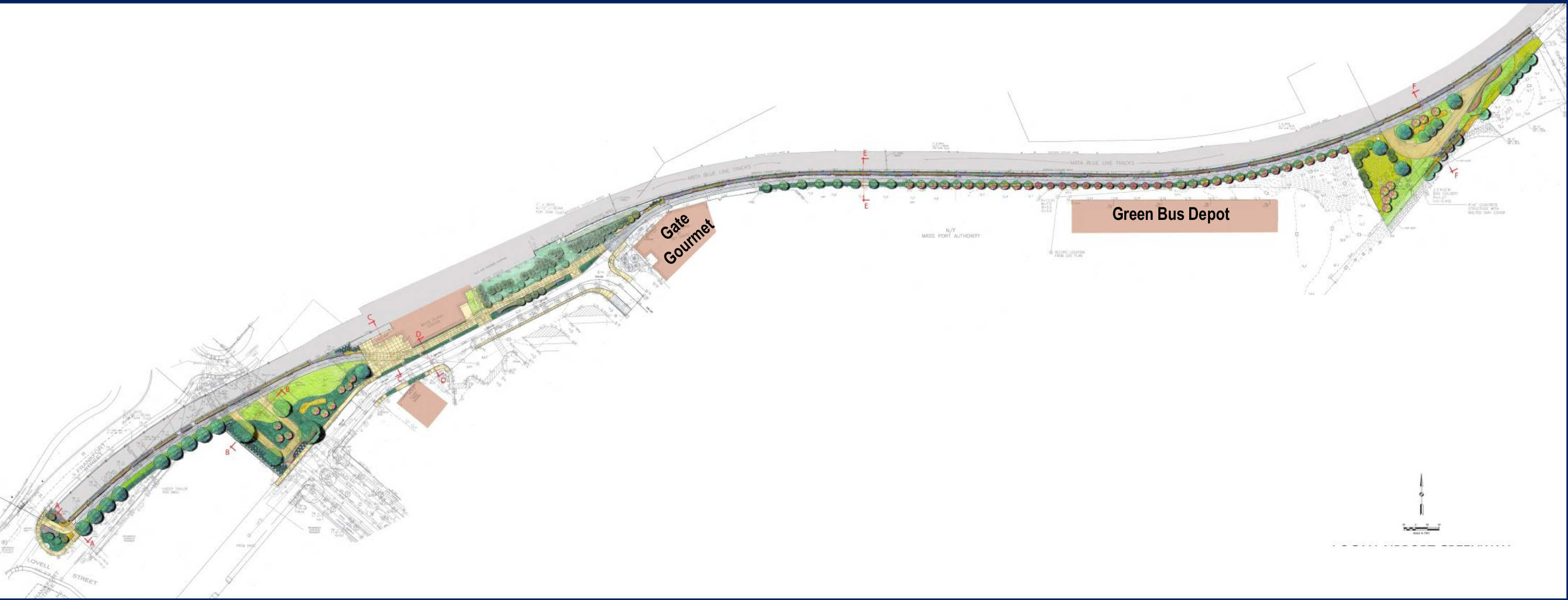

Brown Richardson & Rowe

"Logan Airport Greenway Connector"

Boston, 2012. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of the Massachusetts Port Authority.

Following the leveling of Wood Island Park in the 1960s, the East Boston community fought to preserve its parkland. In 1995, the Trust for Public Land and the Boston Natural Areas Fund outlined plans to develop the East Boston Greenway. Over the next two decades, the organizations worked with community activists, the Massachusetts Port Authority, the Massachusetts Department of Transportation, and the City of Boston to create a linear park that today allows pedestrians and bicyclists to travel 3.3 miles through the heart of East Boston. This plan shows a stretch of the Greenway running from Frankfort and Lovell Streets to the Wood Island Bay Edge Park.

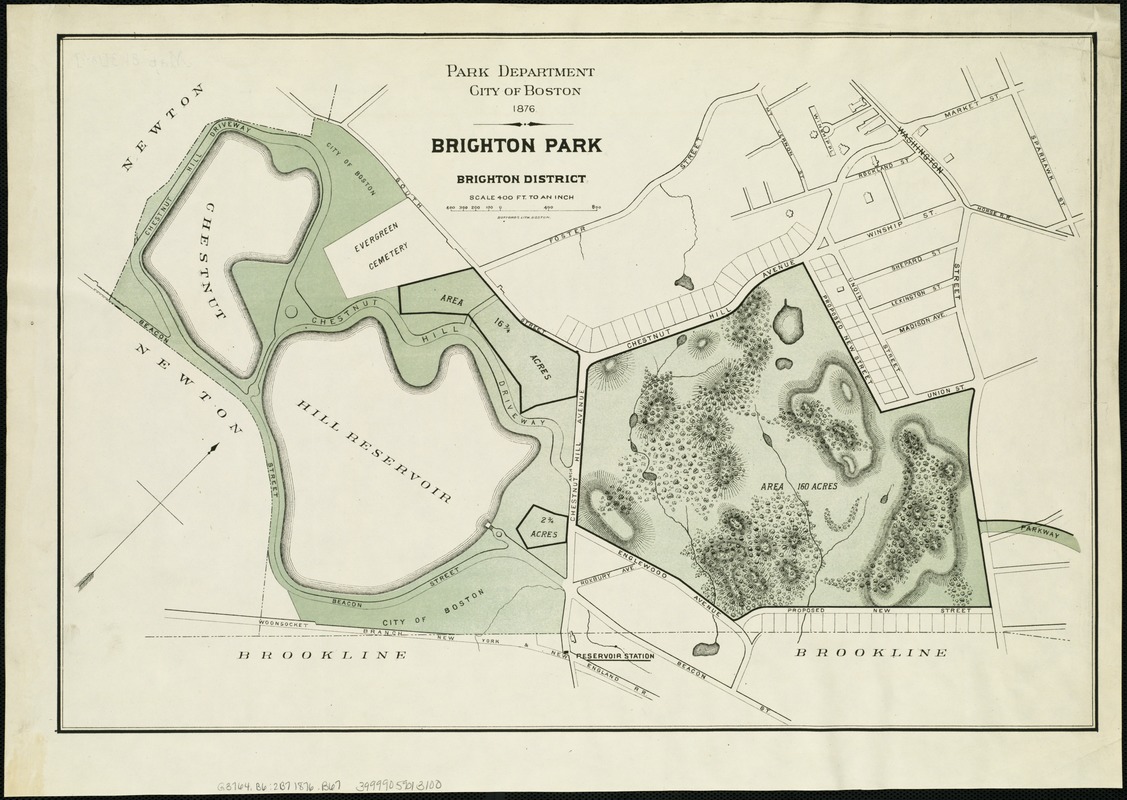

11. Chestnut Hill Reservoir

Boston (Mass.) Park Commissioners

"Brighton Park: Brighton District"

Boston, 1876.

As Boston’s population exploded in the late 19th century, the city constructed the Chestnut Hill Reservoir to supplement the growing demand for water. In addition to its practical purpose, the reservoir was widely extolled in period century guidebooks as “a great pleasure resort” and was a fashionable site for recreational carriage rides. At the time, it was a double reservoir, comprised of two irregular basins divided by a dam, shown here. Only the larger Bradlee Basin remains today, and continues to serve as a recreational park and a back-up water supply for Boston and several other municipalities.

"Chestnut Hill Reservoir"

Boston, [ca. 1865–1965]. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of the Brookline Public Library, Brookline Photograph Collection.

Following the construction of the Chestnut Hill Reservoir, Frederick Law Olmsted conceived the “Chestnut Hill Loop” to join the reservoir with his Boston park system. This colorized photograph shows the carriageway winding through the reservoir complex, described by one tourist guide as a popular drive, its beauty enhanced by “the charming sheet of water, the graceful curvatures of the road, and the neat, trim appearance of the greensward that lines it throughout its entire length.” The picturesque building in the distance is the effluent gate house containing the reservoir’s major control gates.

Oliver Tryon (1883-1922); Massachusetts Metropolitan Water and Sewerage Board

"Distribution Department, Chestnut Hill Reservoir, Lawrence Basin and Pumping Stations, Brighton, Mass., Jul. 3, 1905"

[Boston], 1905. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts State Archives.

This black-and-white photograph shows the Chestnut Hill Reservoir in 1905: Lawrence Basin sits in the foreground, with Bradlee Basin and the Low Service and High Service pumping stations in the background. The popular Chestnut Hill Driveway cuts between the two basins, in turn divided by a manmade dam. Boston College purchased and filled the Lawrence Basin in the 1950s; today, BC’s Alumni Stadium sits in its place.

12. People before Highways

Boston Redevelopment Authority. Comprehensive Planning Division.

"Preliminary Sketch Plan, Boston Regional Core, City of Boston, Metro City Area"

Boston, 1962. Reproduction, 2018.

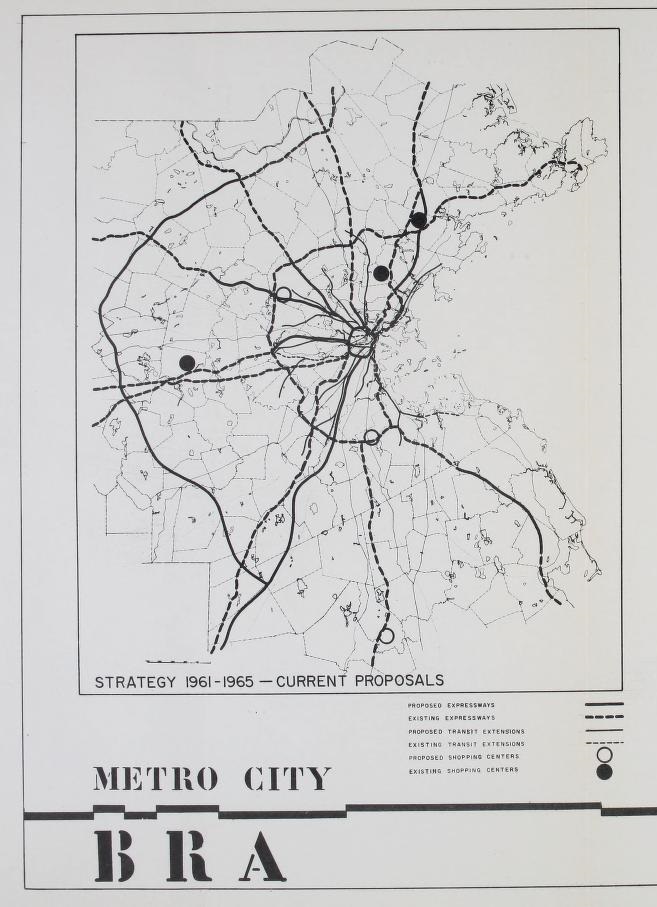

In the 1950s and 1960s, following the construction of the Central Artery through the heart of the city, many Bostonians were wary when transportation planners pushed for the development of two more elevated highways. One, the Inner Belt, was a “ring road” that would loop through Charlestown, Somerville, Cambridge, and Brookline, and back into Boston through the Fenway, Roxbury, and the South End. The Southwest Expressway would connect the city to I-95 by slicing through the communities of Hyde Park, Jamaica Plain, Roxbury, and the South End. Some 7,500 families stood to lose their homes and businesses.

While the state’s Department of Public Works pushed for the construction of Boston’s highways, residents of the affected communities organized. A diverse coalition of anti-highway activists made common cause against the highways’ social, economic, and environmental impacts in their communities. In 1970, Governor Francis Sargent placed a moratorium on highway construction in the city, famously admitting, “Nearly everyone was sure highways were the only answer to transportation problems for years to come. But we were wrong.” Sargent reallocated federal highway funds for mass transit, making Massachusetts the first state to implement what came to be known as the “Boston Provision” in the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1973.

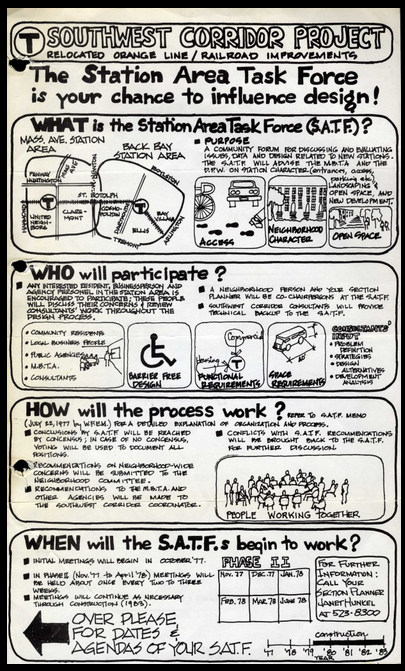

"[Station Area Task Force flyer]," Ann Hershfang Papers

[Boston], 1977.

Courtesy of the University Archives and Special Collections Department, Joseph P. Healey Library, University of Massachusetts Boston: Ann Hershfang papers.

Over the course of the 1970s and 1980s, neighborhood advocates partnered with government transportation authorities to develop the Southwest Corridor project, a plan that improved the existing transit and rail systems, and created the Southwest Corridor Park, a linear park reminiscent of the Emerald Necklace, featuring footpaths, bikeways, playgrounds, basketball and tennis courts, and community gardens. Eight Station Area Task Forces guided the extension of the Orange Line through the Southwest Corridor, shaping the design of the stations and surrounding open spaces. Flyers such as this one recruited neighborhood residents to participate in these community-driven committees.

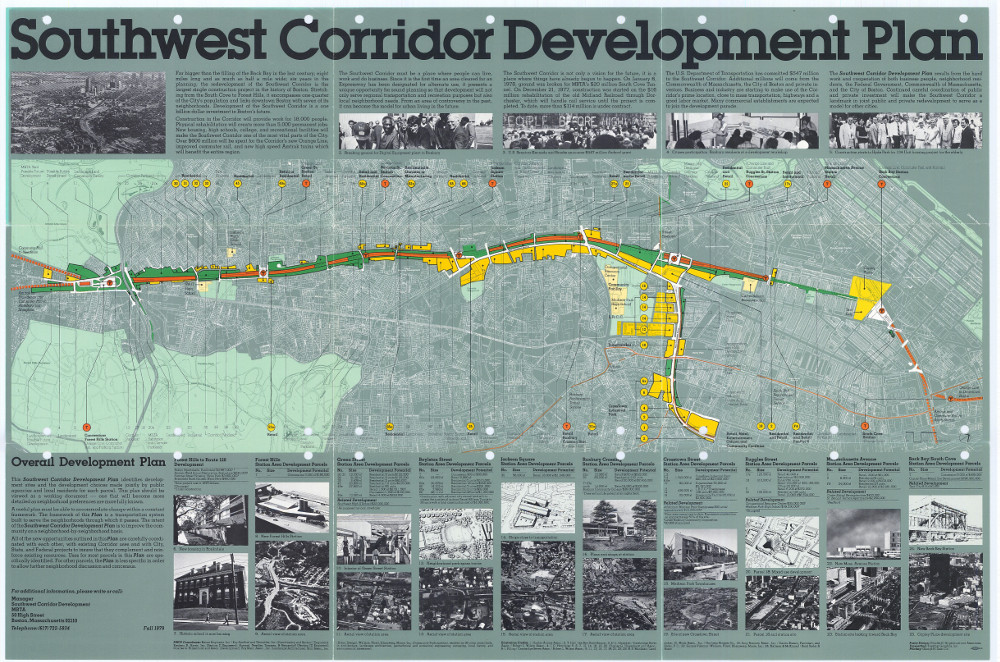

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority

"Southwest Corridor Development Plan"

Boston, 1979. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of the Boston Planning & Development Agency.

Construction on the Southwest Corridor began in 1979, after nine years of rallies, community meetings, public hearings, and environmental impact studies. To ensure that the Corridor project served the needs of the surrounding communities, Station Area Task Forces remained involved in the preparation of the Southwest Corridor Development Plan, one version of which is shown here. It is no accident that the plan prominently features a photograph of a railroad embankment in Jackson Square emblazoned with the words, “PEOPLE BEFORE HIGHWAYS.” Painted by activists, this graffiti slogan became the refrain of the anti-highway movement that culminated in an extraordinary community victory.

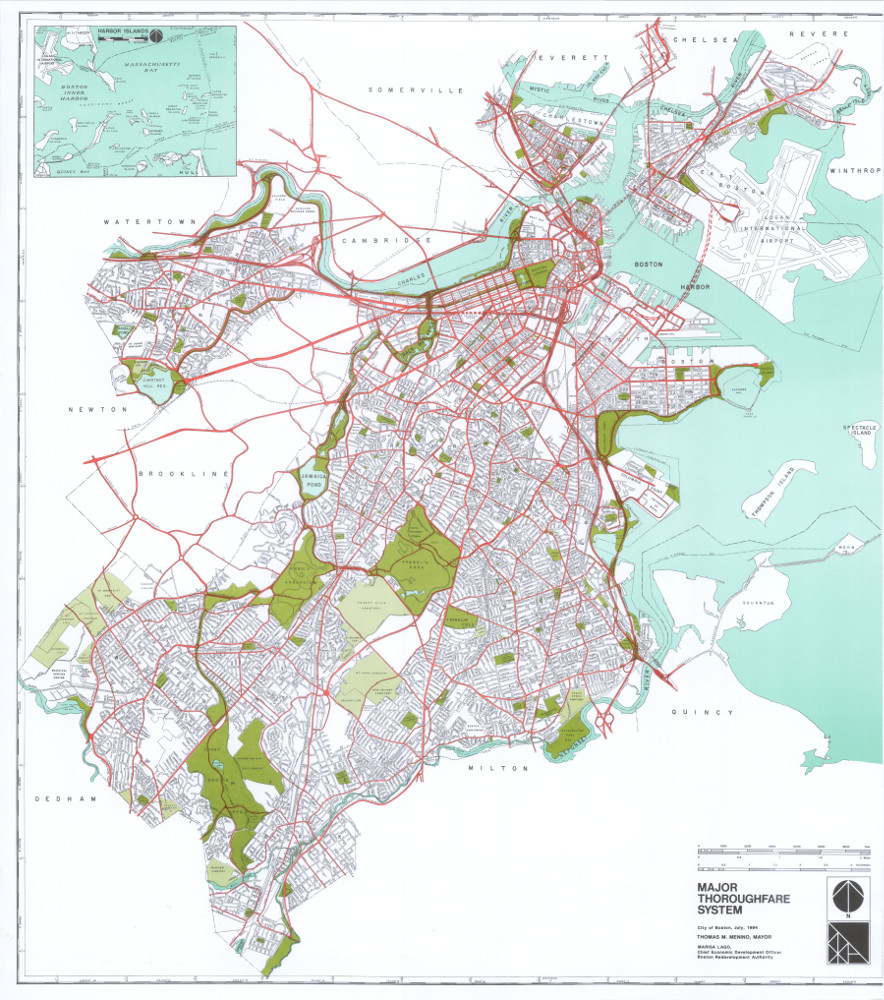

Boston Redevelopment Authority

"Major Thoroughfare System"

Boston, 1994. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of the Boston Planning & Development Agency.

Produced in 1994 by the Boston Redevelopment Authority (now the Boston Planning & Development Agency), this map of Boston’s major roads also highlights a number of the city’s green spaces and mass transit infrastructure. In place of the Southwest Expressway that nearly came to fruition in the middle of the century, a faint set of train tracks denotes the relocated Orange Line running along the Southwest Corridor, and replacing the Washington Street elevated line.

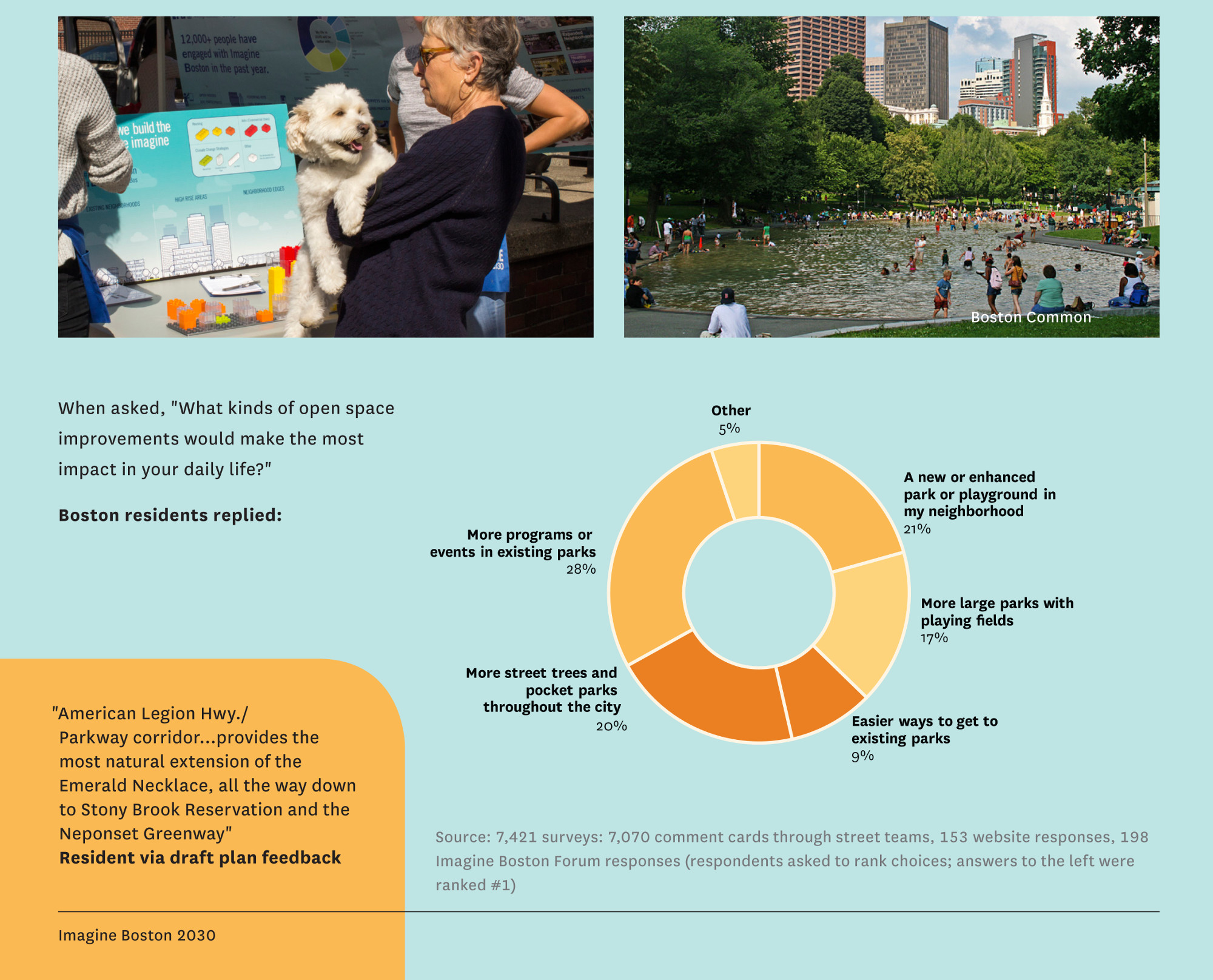

Imagine Boston 2030

“Open Space,” from "Imagine Boston 2030"

Boston, 2017. Reproduction, 2018.

Last year, the City of Boston released "Imagine Boston 2030", its first citywide development plan since the General Plan of 1965 pushed for highway construction at the expense of Boston’s neighborhoods. Following in the footsteps of the Southwest Corridor Development Plan, "Imagine Boston" is intended to serve as a road map for future development in the city. More than 15,000 residents from every neighborhood contributed to the plan through workshops, community meetings, open houses, and surveys. Based on this input, the plan calls for mixed-use development, affordable housing, infrastructure improvements, and more accessible green spaces. Over 7,400 Bostonians shared their hopes for open space improvements, illustrated in this graphic.

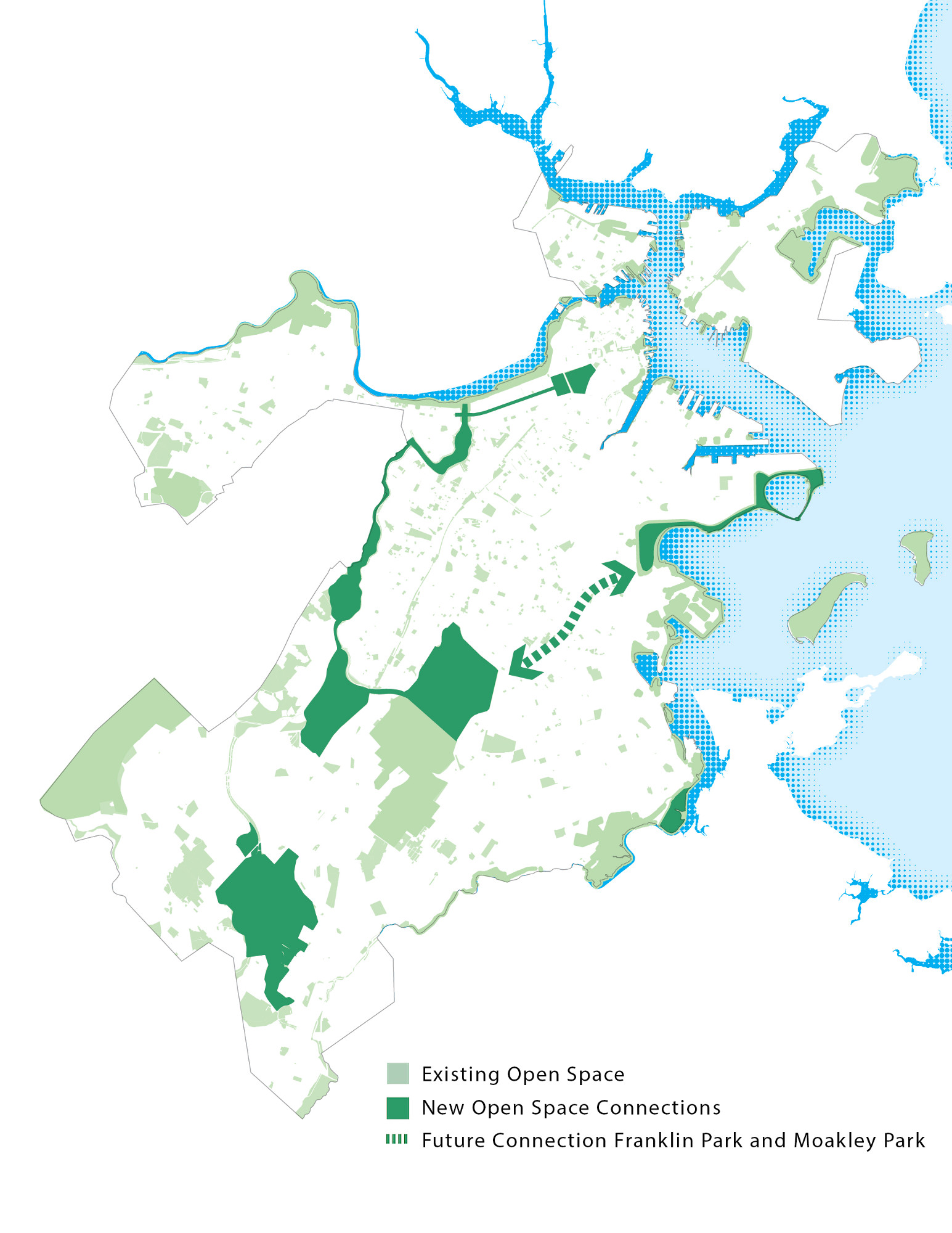

Imagine Boston 2030

“Existing Open Space,” from "Imagine Boston 2030"

Boston, 2017. Reproduction, 2018.

Based on the input of Boston residents, the "Imagine Boston 2030" “Open Space Initiative” calls for the development of “green links” connecting the Emerald Necklace to a citywide network of green spaces, including the waterfront as originally intended by Frederick Law Olmsted. Other initiatives include improving existing parks, developing resilient waterfront parks, and investing in diverse and accessible open spaces in neighborhoods and commercial centers. This map highlights existing open spaces, new open space connections, and the proposed green link between Franklin Park and Moakley Park (represented by the big dotted arrow).

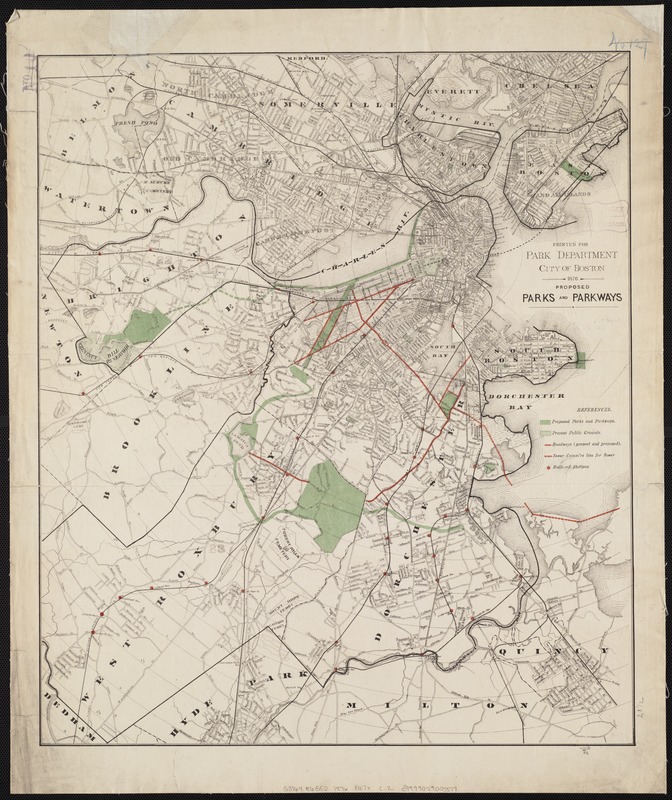

13. The Emerald Necklace

Boston (Mass.) Park Commissioners

"Proposed Parks and Parkways"

Boston, 1876.

In 1876, a group of concerned Bostonians held a public meeting in Faneuil Hall to address the public health issues facing the city: an ever-rising population, widespread illness, a surging death rate, air pollution, and diminishing public space. The solution, they determined, lay in a public park system. This map shows the Boston Park Commissioners’ early vision of a system of connected parks and parkways winding through the city. Two years later, Boston tasked Frederick Law Olmsted with creating such an urban park system; once completed, his “Emerald Necklace” would be the country’s first integrated system of public parks.

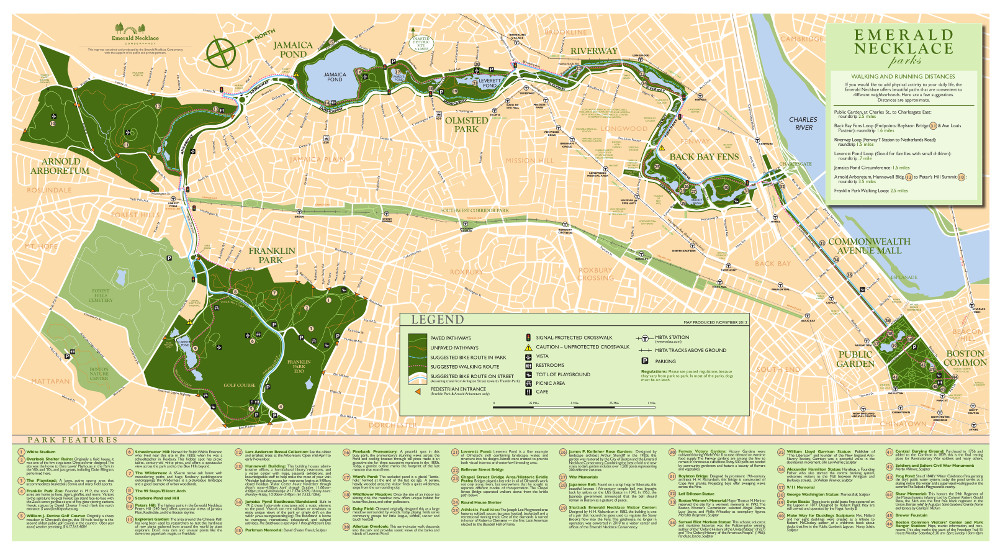

Emerald Necklace Conservancy

"Emerald Necklace Parks"

Boston, 2017. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of the Emerald Necklace Conservancy.

Olmsted adapted the Commissioners’ original plan, designing a park system in tandem with the surrounding natural landscape and built environment. Olmsted’s philosophy of landscape architecture centered on his belief that city dwellers might heal their physical and social ills through exposure to the natural landscape. He intended his park system to be an integral part of the city: a green oasis freely accessible to all. Today, the Emerald Necklace runs over seven miles from end to end, meandering from Boston Common to Franklin Park. The parks designed by Olmsted are managed by the Emerald Necklace Conservancy in partnership with the Boston Parks & Recreation Department, Brookline Parks and Open Space, Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation. The “pre-Olmsted” parks—Boston Common, the Public Garden, and the Commonwealth Avenue Mall—are maintained by the Friends of the Public Garden and the Boston Parks & Recreation Department.

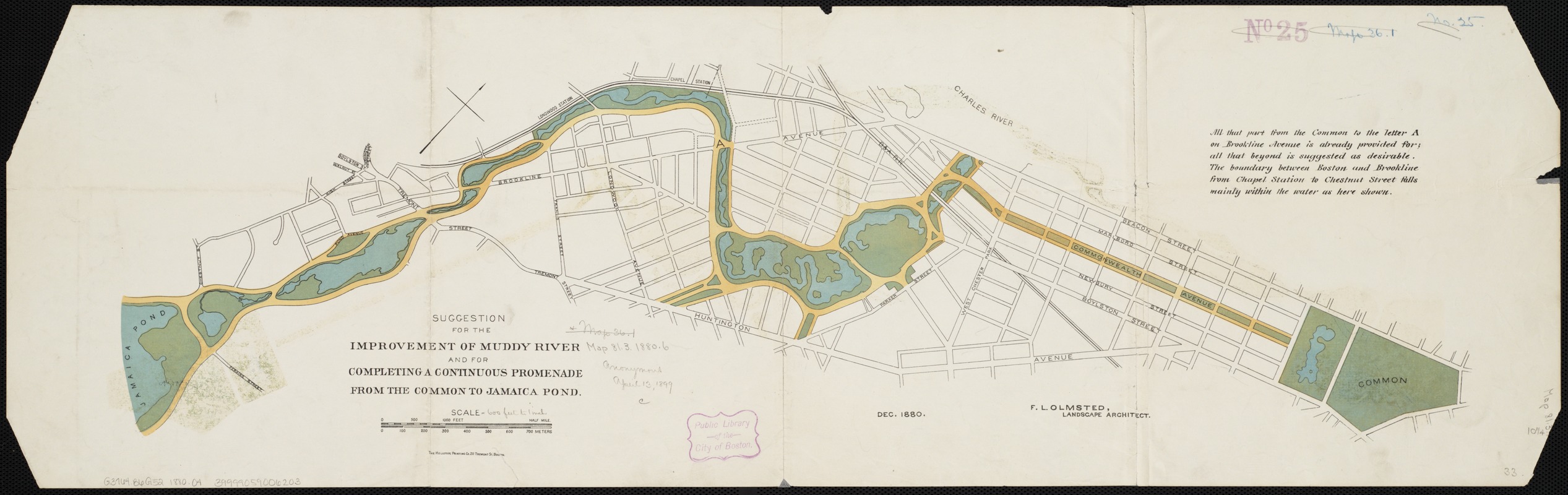

Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903)

"Suggestion for the Improvement of Muddy River and for Completing a Continuous Promenade from the Common to Jamaica Pond"

Boston, 1880.

Conservation of this piece was funded by an anonymous donor.

Originally part of the Back Bay salt marsh, the narrow, tidal Muddy River formed the boundary between Boston and Brookline. By 1880, urban growth had taken its toll, and the once-flowing tributary was notoriously polluted and prone to flooding. The simple schematic plan shown here was Olmsted’s preliminary design for improving the waterway. In it, he sculpted the erratic river into a gently meandering stream, and transformed the swamp south of Tremont Street into a large pond. Olmsted would later alter this plan, going so far as to reroute the river and shift the Boston-Brookline border; this change was legally adopted in 1890.

Marion Pressley/Pressley Associates

"Rendering – Muddy River Restoration Project, Phase 1 (now Boston’s Justine Mee Liff Park)"

Boston, 2012. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of the Muddy River Restoration Project Maintenance and Management Oversight Committee.

In 1959, a stretch of the Muddy River was forced into narrow underground culverts, or tunnels, to accommodate a parking lot, creating a “missing link” in the Emerald Necklace and leaving the area once again vulnerable to flooding. For decades, local activists, advocacy groups, and government officials worked to rehabilitate the river. In 2016, the long-buried stretch of river was “daylighted,” or unearthed, as part of the Muddy River Restoration Project, an effort to preserve the historic landscape, mitigate flood risk, improve water quality, and restore the local habitat. Created in 2012, this artist’s rendering imagined what the river might look like after daylighting.

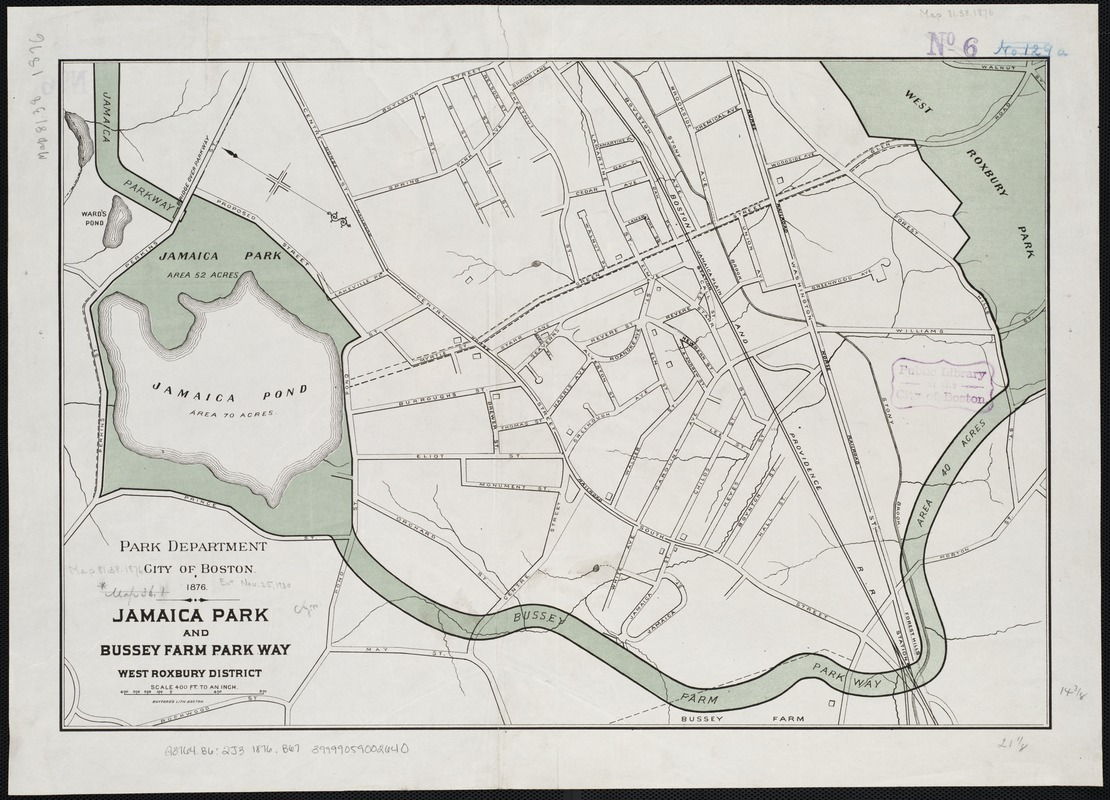

Boston (Mass.) Park Commissioners

"Jamaica Park and Bussey Farm Parkway: West Roxbury District"

Boston, 1876.

Leon H. Abdalian (1884-1967) and George A. Braun

"Jamaica Pond, Perkins Street, Parkman Drive Side"

[Boston], 1928. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Print Department, Leon Abdalian Collection.

Boston’s largest body of fresh water, Jamaica Pond had long served both as a recreation spot and water source for the city. To Olmsted, the pond was a natural setting for a park, describing it in 1882 as “a natural sheet of water, with quiet, graceful shores, rear banks of varied elevation and contour, for the most part shaded by a fine natural forest-growth.” Unlike other parks in the Emerald Necklace, Olmsted did relatively little to alter the terrain. Shown here, Jamaica Park connects to the Necklace by two parkways: Jamaicaway to the north, and Arborway, formerly Bussey Farm Parkway.

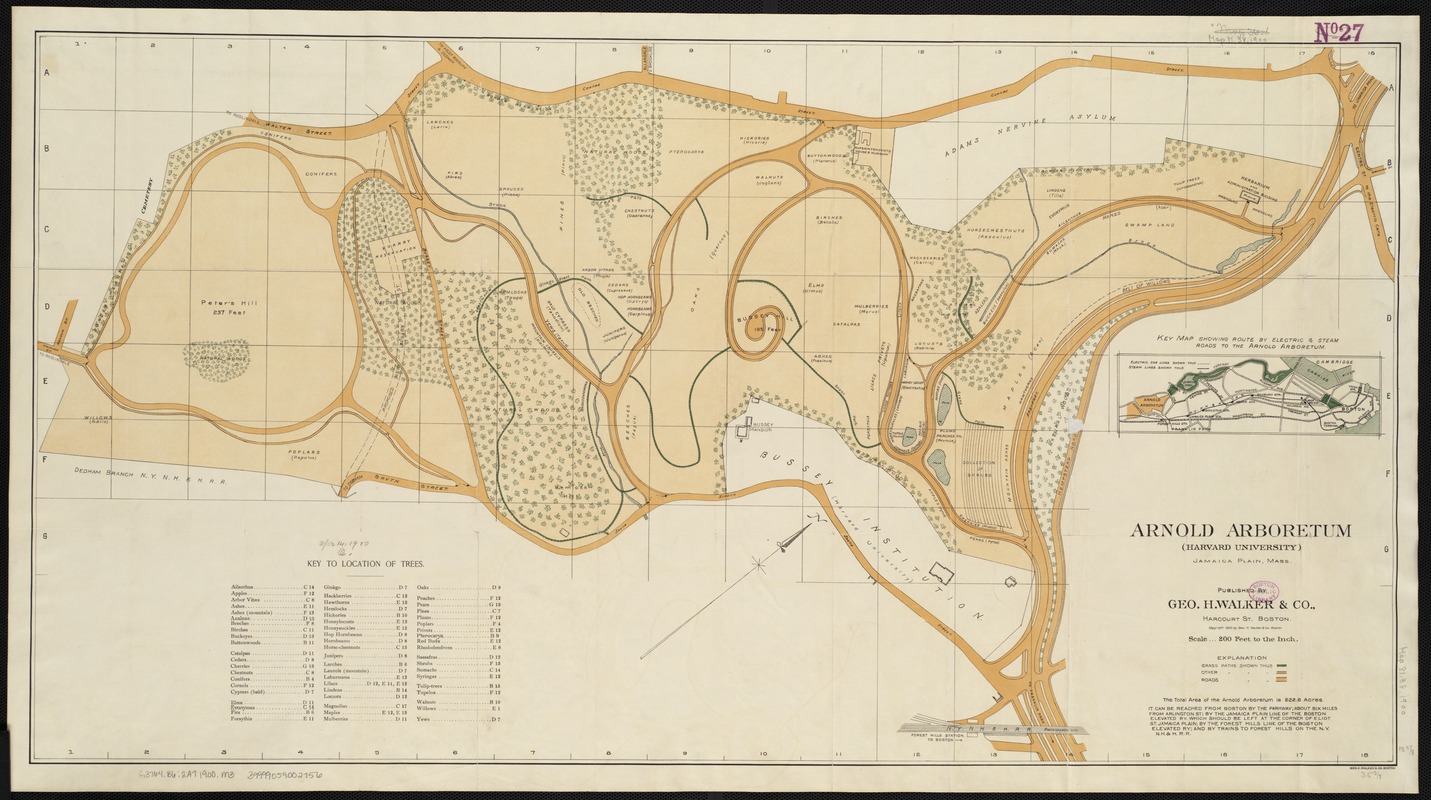

Geo. H. Walker & Co.

"Map of Arnold Arboretum Showing Location of the Trees and Shrubs"

Boston, [1900].

Leon H. Abdalian (1884-1967) and George A. Braun

"Arnold Arboretum, Lilacs on the Hilltop"

[Boston], 1933. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Print Department, Leon Abdalian Collection.

Leon H. Abdalian (1884-1967) and George A. Braun

"Path in Arnold Arboretum"

[Boston], 1920. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Print Department, Leon Abdalian Collection.

Arnold Arboretum’s design was the result of a collaboration between Frederick Law Olmsted and amateur horticulturalist Charles Sargent. Situated on the former site of the Bussey family farm, the Arboretum was established in 1872 with the bequest of James Arnold, a New Bedford whaling merchant. In 1882, Harvard and the City of Boston reached a unique arrangement: Harvard transferred the Arboretum’s land to the City as part of its public park system; in turn, the City leases the property to Harvard for a thousand years, leaving control of the collections with Arboretum staff. Created in 1900, this map shows the locations of trees, shrubs, and pathways designed by Olmsted, which remain largely unchanged to this day.

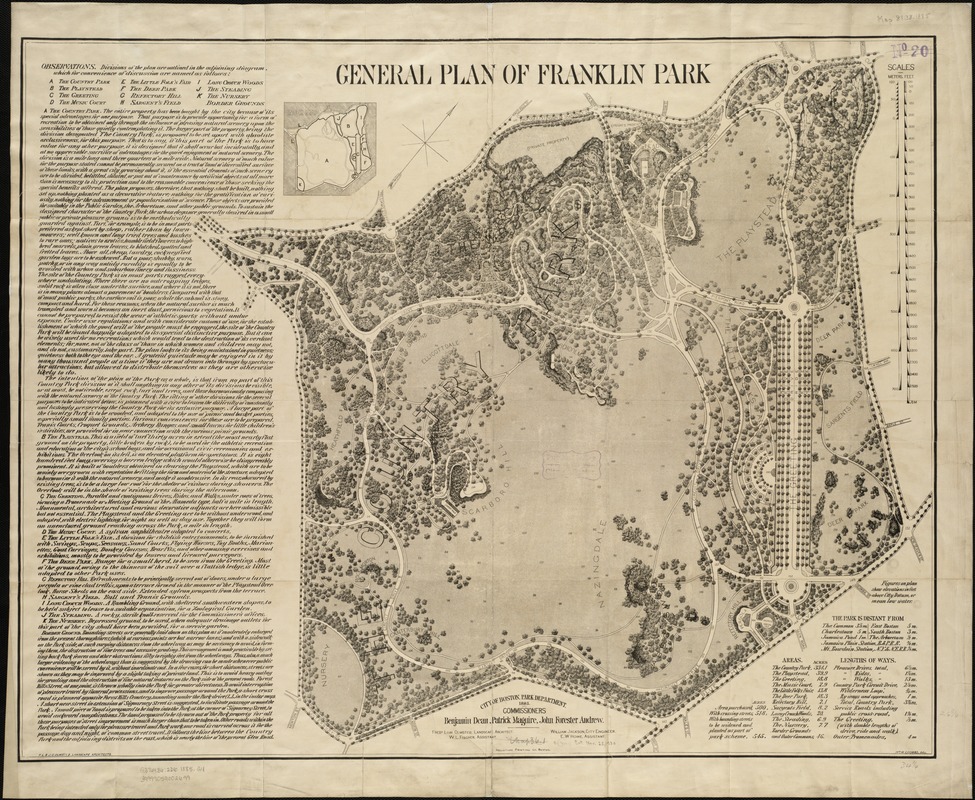

Leon H. Abdalian (1884-1967) and George A. Braun

"Rock Garden, Franklin Park, Taken from Tower"

[Boston], 1936. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Print Department, Leon Abdalian Collection

Boston’s largest park, Franklin Park is considered the “crown jewel” of the Emerald Necklace. To Olmsted, rural scenery offered a physical and visual contrast with the crowding and artificiality of the city, allowing visitors to relax physically and emotionally, consciously and unconsciously. This park plan features dense marginal text in which Olmsted laid out his vision for a country park adorned simply with paths, natural ledges, and native plantings, trimmed not by lawn mowers but by grazing sheep. Franklin Park never fully achieved Olmsted’s original vision, but evolved to feature a woodland preserve and open fields, as well as a zoo, public golf course, pedestrian and bridle paths, a stadium, and other recreational facilities.

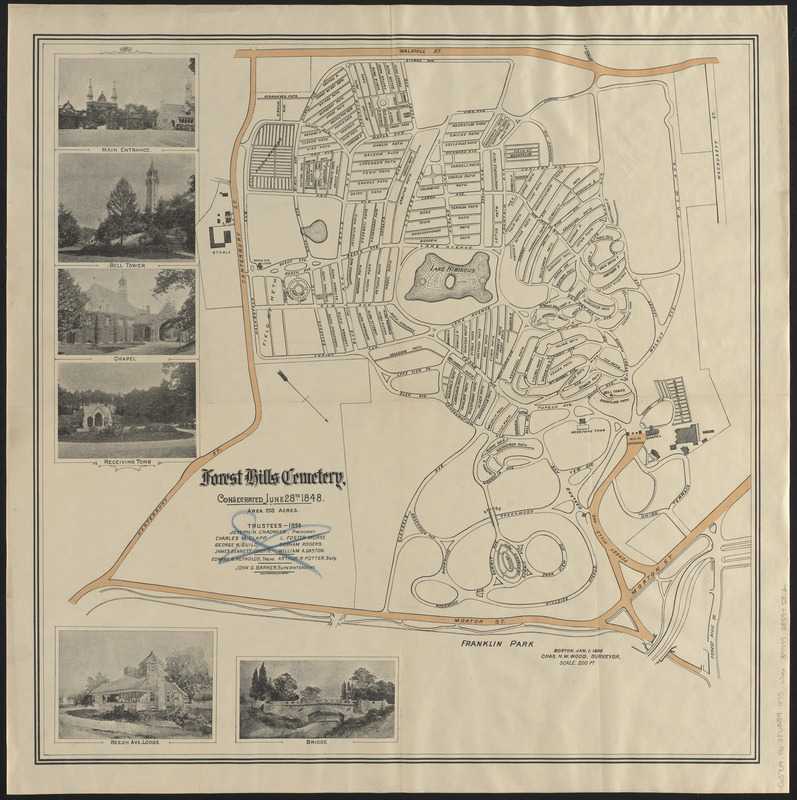

Charles H. W. Wood

"Forest Hills Cemetery"

Boston, 1895.

Conservation of this piece was funded by an anonymous donor.

"View across Lake Hibiscus -- Forest Hills Cemetery, Boston, Mass."

Boston, [ca. 1930–1945]. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Print Department, The Tichnor Brothers Collection.

In 1848, Henry Dearborn, the mayor of Roxbury, spearheaded the project to develop Forest Hills Cemetery to alleviate overcrowded burial grounds. Nearly two decades prior, Dearborn had designed Mount Auburn Cemetery, the nation’s first rural cemetery. Like its predecessor, Forest Hills was designed in the picturesque romantic style, featuring curvilinear paths and roads lined by naturalistic plantings, and dramatic tombs and monuments. Today, Forest Hills remains an active burial ground, open-air museum, green space, and arboretum. Though not part of the Emerald Necklace, Forest Hills abuts Franklin Park and is a short distance from Arnold Arboretum, forming an informal supplement to the park system.

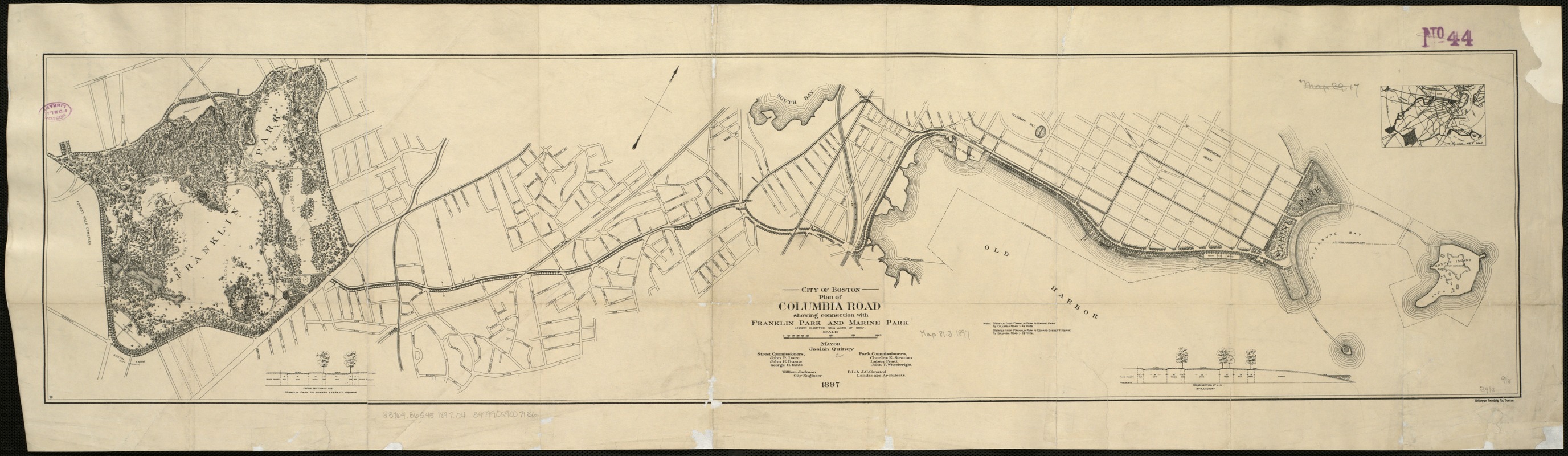

Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903)

"City of Boston Plan of Columbia Road, Showing Connection with Franklin Park and Marine Park: Under Chapter 394 Acts of 1897"

Boston, 1897.

When Olmsted first conceived the Boston park system, Columbia Road was intended to be a greenway connecting Franklin Park to Marine Park, as shown in this 1897 plan. This vision was never realized, as Columbia Road was already lined with buildings and used for commercial traffic. Today, Columbia Road is a busy thoroughfare bisected by a sparsely planted median. As part of its 2030 vision for a healthier, better connected city, the City of Boston plans to develop the Columbia Road Greenway, a green corridor with improved pedestrian and bike paths. The proposed greenway will link Franklin and Moakley Parks, finally completing the Emerald Necklace.

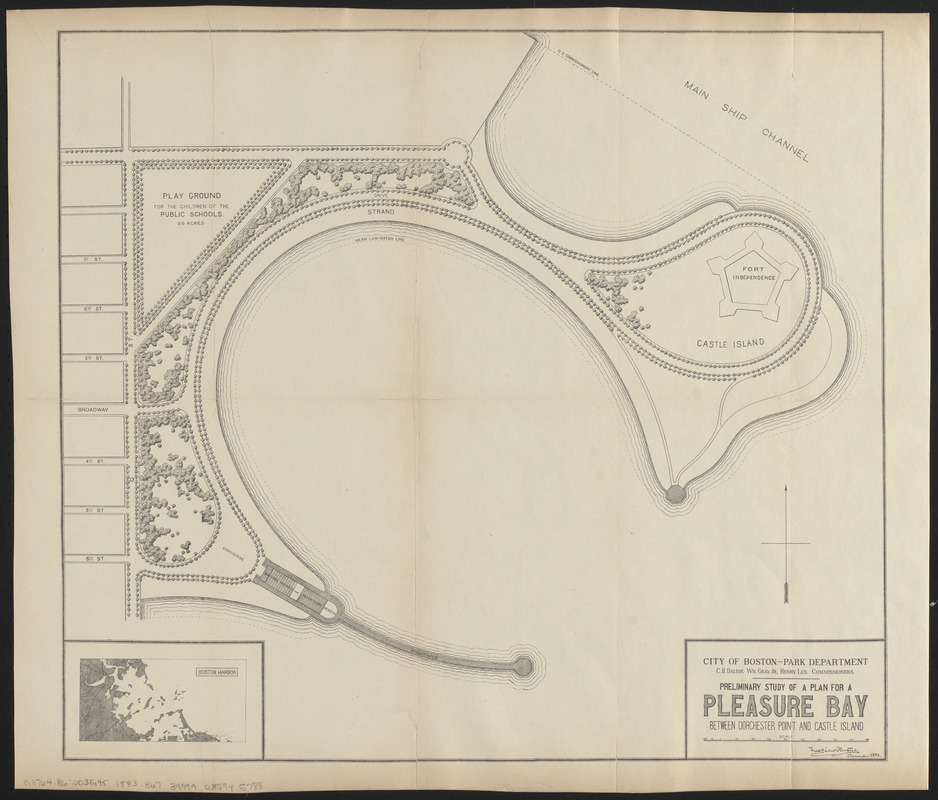

Boston (Mass.) Department of Parks

"Preliminary Study of a Plan for a Pleasure Bay between Dorchester Point and Castle Island"

Boston, 1884.

Conservation of this piece was funded by an anonymous donor.

Leslie Jones (1886-1967)

"Beach Crowd at Pleasure Bay, City Point, South Boston"

Boston, [ca. 1930]. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection.

Olmsted envisioned Marine Park as the final jewel in the Emerald Necklace, linked to Franklin Park by a greenway along Columbia Road. The greenway was never constructed and Marine Park remains disconnected from the park system. However, the City of Boston has proposed a green link along Columbia Road to realize Olmsted’s vision. Shown here, Olmsted’s plan expanded City Point, shaping a semi-circular cove for swimming and boating. The plan includes a boardwalk for promenades along the water and a playground for schoolchildren. In the 1920s, Castle Island was connected to Marine Park by filling land and constructing stone causeways and mechanical tide gates.

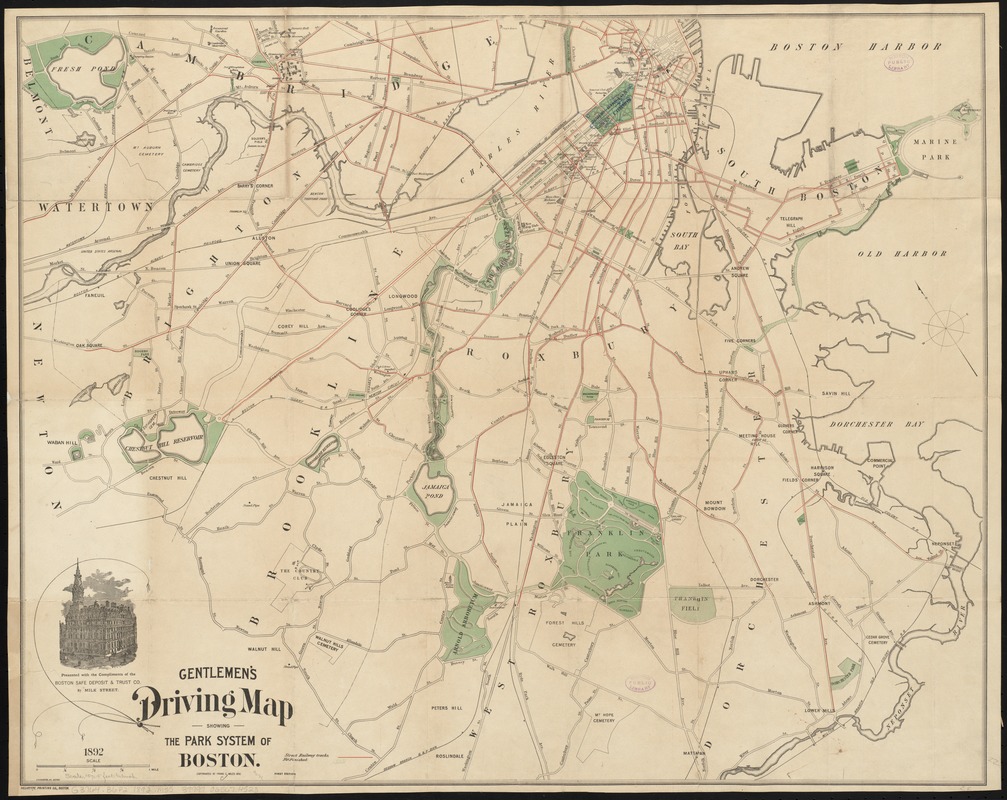

Frank C. Miles

"Gentlemen's Driving Map Showing the Park System of Boston"

Boston, 1892.

Toward the end of the 19th century, industrial advances made carriages more affordable, leading to increased mobility for many. Pleasure driving in horse-drawn vehicles, a leisure activity once reserved for wealthier Americans, was now a more widely accessible hobby. Olmsted’s parks featured carriage promenades, and the parkways connecting the Emerald Necklace system were designed as pleasure routes for carriages. Produced in 1892, this map shows Boston’s carriage drives, highlighting the park system; the whips emanating from the title hint at the map’s audience. The map also features streetcar routes for those wishing to reach the parks by another, more affordable, means.

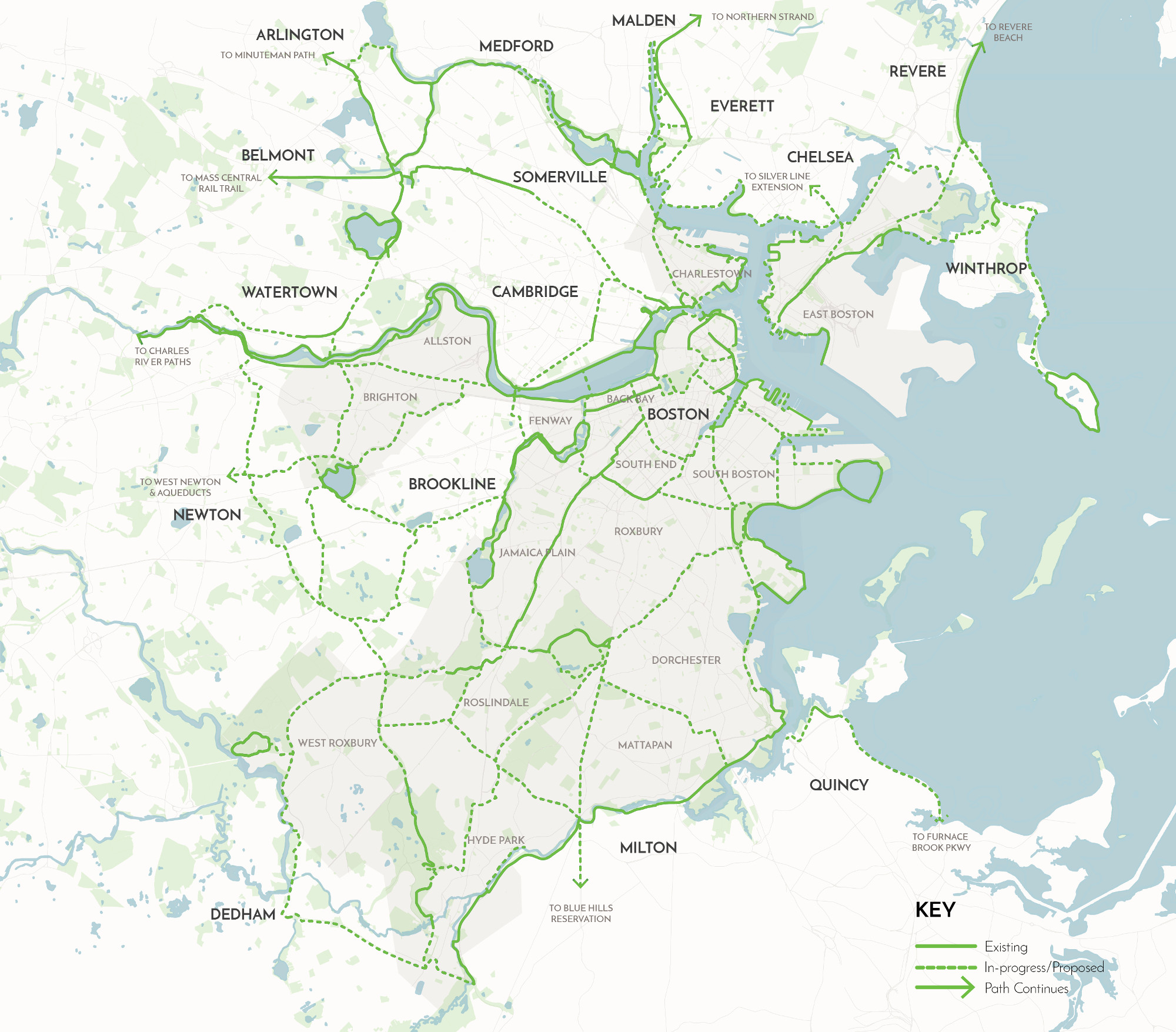

LivableStreets Alliance

"The Emerald Network"

[Boston], 2015. Reproduction, 2018.

Courtesy of LivableStreets Alliance.

Greenways come in many shapes and sizes, but can generally be defined as linear, vegetated, multi-use paths that connect and are comprised of other open space areas. Although Olmsted’s vision for a continuous park loop has not yet been realized, today there are 100 miles of greenway infrastructure in Boston and its adjacent cities. The LivableStreets Alliance is working with park groups, community volunteers, and other organizations to develop a 200-mile network of greenways connecting every neighborhood between the Mystic River in the north and the Neponset River in the south. This map shows the Emerald Network’s existing and proposed greenways.

Bibliography

Allison, Robert. A Short History of Boston. Beverly, Massachusetts: Commonwealth Editions, 2004. [F73.3 .A45 2004]

Arrison, Julie. Franklin Park. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2009. [F73.65 .F83A77 2009x]

Ball, Joanne. "A Future Grows from Struggles of the Past." Boston Globe, November 03, 1986. Accessed February 12, 2018. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1955988517?accountid=9675.

Baxter, Sylvester. "Economic and Social Influences of the Bicycle," The Arena, VI, October 1892, 580-583. [PER AP2 .A6]

Berg, Shary Page. Cultural Landscape Report: The Esplanade, Boston, Massachusetts. Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2007. https://esplanadeassociation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Esplanade-CLR-Final-from-Shary-Berg-8.14.12-sm.pdf.

Beveridge, Charles. “Olmsted — His Essential Theory.” National Association for Olmsted Parks. Accessed February 15, 2018. http://www.olmsted.org/the-olmsted-legacy/olmsted-theory-and-design-principles/olmsted-his-essential-theory.

“The Blue Hills Reservation: Foot Paths and Roads for Horseback Riders Will be Ready in the Spring.” Boston Globe, January 31, 1894.

Boston Landmark Commission. Report of the Boston Landmark Commission on the Potential Designation of the Chestnut Hill Reservoir and Pumping Stations as a Landmark. Boston, Massachusetts: Environment Department, 1989. https://www.cityofboston.gov/images_documents/Chestnut%20Hill%20Reservoir%20Pump%20Stations%20Study_tcm3-19719.pdf.

Boston (Mass.). Board of Health. A Communication From the City Physician on Asiatic Cholera: Is It A Contagious Disease? Boston, Massachusetts: J. E. Farwell, 1866. [7791.160]

Boston (Mass.). Committee on Internal Health. Report of the Committee on Internal Health on the Asiatic Cholera, Together With A Report of the City Physician on the Cholera Hospital. Boston, Massachusetts: J.H. Eastburn, 1849. [3765.54 No. 8]

Boston (Mass). Parks and Recreation Department. "Open Space and Recreation Plan 2015 – 2021." Boston.gov. 2015. Accessed February 24, 2018. https://www.boston.gov/environment-and-energy/open-space-and-recreation-plan-2015-2021.

Boston (Mass.). Parks and Recreation Department. "Urban Wilds Initiative." Boston.gov. July 14, 2016. Accessed February 24, 2018. https://www.boston.gov/environment-and-energy/urban-wilds-initiative.

Boston (Mass.). Superintendent of Common and Public Grounds. Annual Report of the Superintendent of Common and Public Grounds. Boston, Massachusetts: Rockwell and Churchill, 1889. [6359.45]

Boston (Mass.). Transportation Department. Go Boston 2030: Vision and Action Plan. 2017. https://www.boston.gov/sites/default/files/go_boston_2030_-_full_report_to_download.pdf.

Boston Preservation Alliance. East Boston Preservation Priorities Report, December 2011. Boston, 2011. http://www.bostonpreservation.org/programs/documents/EASTBOSTONFINALNPPREPORT.pdf.

Boston Redevelopment Authority. 1965/1967 General Plan for the City of Boston and the Regional Core. 1964. Accessed February 13, 2018. https://archive.org/details/19651967generalp00bost.

Boston Redevelopment Authority. Preliminary Sketch Plan, Boston Regional Core, City of Boston, Metro City Area. 1962. [GOV DOCS BRA/5031]

Boston Water Works. Description of the Boston Water Works. Chicago, Illinois: Engineering News, 1878. [5943.53]

Bowen, Abel. Bowen's Picture of Boston, or the Citizens and Stranger's Guide to the Metropolis of Massachusetts, and Its Environs. Boston, Massachusetts: Otis, Broaders and Company, 1838. [CS43 .G44x]

Charles A. Maguire and Associates. The Master Highway Plan for the Boston Metropolitan Area Submitted to Robert F. Bradford, Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts by the Joint Board for the Metropolitan Master Highway Plan. Boston, Massachusetts, 1948. [FINE ARTS 8123.04-331]

"The Corridor is a Definite Plus." Boston Globe, December 3, 1979. Accessed February 12, 2018. https://search.proquest.com/docview/747355452?accountid=9675.

Crocket, Karilyn. People before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and a New Movement for City Making. Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press, 2018. [HE355.3.C58 C76 2018]

Cushing, Elizabeth Hope. “‘So Near the Metropolis’—Lynn Woods, a Sylvan Gem in an Urban Setting.” Arnoldia 48, no. 4 (1988): 37-51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42954328.

Donham, Parker. "War Protest due Today on Common." Boston Globe, April 15, 1970. Accessed February 5, 2018. https://search.proquest.com/docview/367015982?accountid=9675.

Dumanoski, Diane. “Parks, Lost and Found.” Land & People, Spring 2001. https://www.tpl.org/magazine/parks-lost-and-found%E2%80%94landpeople#sm.0001ylf5ogexgfjmvu01glslspinj.

Eliot, Charles and Olmsted, Olmsted, & Eliot. Vegetation and Scenery in the Metropolitan Reservations of Boston. Boston, Massachusetts: Lamson, Wolffe and Company, 1898. [RARE BKS SB483.B73 E6]

Eliot, Charles W. Charles Eliot, Landscape Architect. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin, 1902. [SB470.E6 E6]

Eliot, Charles W., Donald M. Graham, and David A. Crane. "Boston: Three Centuries of Planning." Ekistics 18, no. 105 (1964): 81-84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43614079.

Encyclopædia Britannica, s.v. "Boston Fire of 1872," accessed February 7, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/event/Boston-fire-of-1872.

Foster, Catherine. “Subway with a Park on Top: Boston's Southwest Corridor Has Train Tracks below, Green Areas and Recreation above.” Christian Science Monitor, February 24, 1989. Accessed February 12, 2018. https://www.csmonitor.com/1989/0224/dorange.html.

Friends of Post Office Square. “History of Boston’s Post Office Square.” Norman B. Leventhal Park. 2016. Accessed February 7, 2018. http://www.normanbleventhalpark.org/about-us/history-of-post-office-square/.

Friends of the Public Garden. Boston Common. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2005. [F73.65 .B67B67 2005]

Friends of the Public Garden. The Public Garden, Boston. Boston, Massachusetts: Friends of the Public Garden, Inc., 2000. [F73.65 .P83 2000x]

Grauerholz, Mary. “Smart Park.” USGBC+, May-April 2017. Accessed February 7, 2018. http://plus.usgbc.org/smart-park/.

Haglund, Karl. Inventing the Charles River. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2003. [F72 .C46H33 2003]

Hardy, Stephen. How Boston Played. Knoxville, Tennessee: The University of Tennessee Press, 2003. [GV584.5.B6 H37 2003]

Hutton, Carole. "7000 March in Hub to Back Job Rights for Homosexuals." Boston Globe, June 19, 1977. Accessed February 5, 2018. https://search.proquest.com/docview/747234723?accountid=9675.

Imagine Boston 2030. Imagine Boston 2030. 2017. Accessed February 13, 2018. https://imagine.boston.gov/imagine-boston-plan/.

Johnson, Glen. "Artery Officials, Land Trust Tussle Over Park Payment." Boston Globe, February 7, 2005. Accessed February 24, 2018. https://search.proquest.com/docview/404940404?accountid=9675.

Jordan, Robert. "The Economy: $300m SW corridor plan reborn." Boston Globe, February 11, 1976. Accessed February 12, 2018. https://search.proquest.com/docview/656118334?accountid=9675.

Jordan, Robert. "Rapid Change Foreseen for Roxbury Properties." Boston Globe, November 23, 1985. Accessed February 12, 2018. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1821500778?accountid=9675.

Kenney, Michael. "Thousands Pack Common for Vietnam Moratorium." Boston Globe, April 16, 1970. Accessed February 12, 2018 https://search.proquest.com/docview/367038675?accountid=9675.

King, Moses. King’s Handbook of Boston, 5th ed. Cambridge, Massachusetts: M. King, 1883.

Kinney, Thomas A. The Carriage Trade: Making Horse-drawn Vehicles in America. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004. [HD9709.5 .U62K56 2004]

Kittredge, Walter. "The Middlesex Fells, a Flourishing Urban Forest." Arnoldia 70, no. 3 (2013): 2-11. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42955541.

Levenson, Michael. "The Greenway is Putting Down Roots." Boston Globe, August 18 2013. Accessed February 6, 2018. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1425572622?accountid=9675.

Krieger, Alex, David Cobb, and Amy Turner, eds. Mapping Boston. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1999. [GA430 .M36 1999]

MacDonald, Christine. "Jockeying For Parks, Recreation." Boston Globe, December 12, 2004. Accessed February 24, 2018. https://search.proquest.com/docview/404926623?accountid=9675.

Marchione, William P. “Water for Greater Boston.” Brighton-Allston Historical Society. 2001. Accessed February 8, 2018. http://www.bahistory.org/HistoryWaterForBoston.html.

Martin, Justin. Genius of Place: The Life of Frederick Law Olmsted. Boston, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press, 2011. [SB470 .O5M37 2011]

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. Southwest Corridor Development Plan. Boston, Massachusetts, 1979. [GOV DOCS M3/TA/79.2 or BRA/3033]

Massachusetts Committee on Charles River Dam. Evidence and Arguments before the Committee on Charles River Dam Appointed Under Resolves of 1901, Chapter 105: December 16, 1901 to January, 1903. Boston, Massachusetts: Wright & Potter Printing Company, 1903.

Massachusetts Committee on Charles River Dam. Report of the Committee on Charles River Dam. Boston, Massachusetts: Wright & Potter Printing Company, 1903. [TC425.C4 A3 1903]

Massachusetts. Department of Conservation and Recreation. Charles River Basin Master Plan. 2002. Accessed February 8, 2018. https://www.mass.gov/guides/master-plans.

Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation. Chestnut Hill Reservation Resource Management Plan. 2006. Accessed February 9, 2018. https://www.mass.gov/service-details/chestnut-hill-reservation-resource-management-plan.

Massachusetts Department of Environmental Management. The Emerald Necklace Parks Master Plan. 2001. [GOV DOCS M3/EM/01.2]

Massachusetts Department of Public Works. Preliminary Relocation Survey: Roxbury District of the City of Boston. 1965. [GOV DOCS BRA/2227]

Massachusetts Department of Transportation. “The Central Artery/Tunnel Project – The Big Dig.” Massachusetts Department of Transportation. http://www.massdot.state.ma.us/highway/TheBigDig.aspx.

Massachusetts Joint Board upon Improvement of Charles River. Report of the Joint Board Consisting of the Metropolitan Park Commission and the State Board of Health Upon the Improvement of Charles River from the Waltham Line to the Charles River Bridge. Boston, Massachusetts: Wright & Potter Printing Co., 1894. [4454.259]

Massaschusetts. Metropolitan Area Planning Council. “Orange Line Opportunity Corridor Report.” Massachusetts Association of Community Development Corporations. 2013. https://macdc.org/sites/default/files/research/Orange_Line_Opportunity_Corridor_Report.pdf.

Massachusetts Water Resources Authority. “Metropolitan Boston's Water System History.” MWRA Online. September 2, 2015. Accessed February 8, 2018. http://www.mwra.state.ma.us/04water/html/hist1.htm.

“Massport Celebrates Opening of Greenway Connector in East Boston.” Massport.com. August 21, 2014. Accessed February 24, 2018. http://www.massport.com/massport/media/newsroom/massport-celebrates-opening-of-greenway-connector-in-east-boston/.

Morgan, Keith N. "Charles Eliot, Landscape Architect: An Introduction to His Life and Work." Arnoldia 59, no. 2 (1999): 2-22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42954565.

Newton, Norman T. Design on the Land: The Development of Landscape Architecture. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971.

“Norman B. Leventhal Park: Boston, Massachusetts.” American Planning Association. 2018. Accessed February 7, 2018. https://www.planning.org/greatplaces/spaces/2013/leventhalpark.htm.

Olmsted, Frederick Law. Civilizing American Cities: A Selection of Frederick Law Olmsted’s Writings on City Landscape. Edited by S. B. Sutton. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1979. [HT167 .O44 1979x]

Olmsted, Frederick Law. The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted: The Early Boston Years, 1882–1890. Edited by Charles E. Beveridge, Ethan Carr, Amanda Gagel, and Michael Shapiro. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013. [FINE ARTS SB470.O5 A2 1977]

Olmsted, Frederick Law. "Reforesting the Boston Harbor Islands: A Proposal (1887)." Arnoldia 48, no. 3 (1988): 26-27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42955607.

Paneth, Nigel, Peter Vinten-Johansen, Howard Brody, and Michael Rip. “A Rivalry of Foulness: Official and Unofficial Investigations of the London Cholera Epidemic of 1854.” American Journal of Public Health 88, no. 10 (1998): 1545–1553. doi:10.2105/ajph.88.10.1545.

Peterson, Jon A. "The Impact of Sanitary Reform upon American Urban Planning, 1840-1890." Journal of Social History 13, no. 1 (1979): 83-103. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3786777.

Plotkin, A. S. "Sargent Urges More Public Transit." Boston Globe, February 12, 1970. Accessed February 8, 2018. https://search.proquest.com/docview/367086878?accountid=9675.

Pregill, Philip and Nancy Volkman. Landscapes in History: Design and Planning in the Eastern and Western Traditions. Second ed. New York, New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1999. [SB470.5 .P74 1999]

Primack, Mark. "Twenty Years After: The Revival of Boston's Parks and Open Spaces." Arnoldia 48, no. 3 (1988): 10-17. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42955601.

Rawson, Michael. Eden on the Charles: The Making of Boston. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2010. [F73.44 .R39 2010]

Reichenbach, Kristina. "Greenways: Cornucopia of Opportunities." Parkways, Greenways, Riverways: The Way More Beautiful. Edited by Woodward S. Bousquet, Thomas E. Rash, and Mark H. Suggs, 270-275. Boone, North Carolina: Appalachian State University, 1989. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1xp3mr6.37.

Richburg, Julie A. and William A. Patterson. "Historical Description of the Vegetation of the Boston Harbor Islands: 1600-2000." Northeastern Naturalist 12 (2005): 12-30. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4130738.

The Rose Kennedy Greenway Conservancy. "History." The Rose Kennedy Greenway. 2018. Accessed February 07, 2018. https://www.rosekennedygreenway.org/about-us/greenway-history/.

Rosenberg, Charles E. The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849, and 1866. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press, 1987. [RC131.A2 R67 1987]

Sammarco, Anthony Mitchell. East Boston. Dover, New Hampshire: Arcadia Publishing, 1997. [F73.68.E2 S36 1997x]

Sammarco, Anthony Mitchell. Forest Hills Cemetery. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2009. [F73.61 .A5S35 2009x]

Scott, Frank. “The Palaces of America.” The Gardener's Monthly and Horticultural Advertiser. Vol. 11. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Brinckloe & Marot, 1869. [PER 7993.50]

Sears, Robert. A Pictorial Description of the United States; Embracing the History, Geographical Position, Agricultural and Mineral. Boston, Massachusetts: John A. Lee & Co., 1876.

Seasholes, Nancy. Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2003. [F73.3 .S46 2003]

Snow, John. On the Mode of Communication of Cholera. London, England: J. Churchill, 1849.

Stanwood, Edward. Boston Illustrated. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1886.

Stark, J. H. Illustrated History of Boston Harbor: Compiled from the Most Authentic Sources, Giving a Complete and Reliable History of Every Island and Headland in the Harbor, from the Earliest Date to the Present Time. Boston, Massachusetts: Photo-Electrotype Company, 1880. [F73.63 .S79 1880]

Stratton, Ezra M. The World on Wheels; Or, Carriages, With Their Historical Associations from the Earliest To the Present Time, Including a Selection from the American Centennial Exhibition. New York, New York, 1878. https://archive.org/details/cu31924003597071.

Toomey, Daniel. Massachusetts of Today: A Memorial of the State, Historical and Biographical, Issued for the World's Columbian Exposition at Chicago. Boston, Massachusetts: Columbia Publishing Company, 1892.

U.S. National Park Service. Boston Harbor Islands, a National Park Area, General Management Plan: Environmental Impact Statement. Boston, Massachusetts: National Park Service, 2000. [GOV DOCS F73.63.B66 2000x]

U.S. National Park Service. “Forest Hills Cemetery.” Massachusetts Conservation. Accessed February 21, 2018. https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/massachusetts_conservation/forest_hills_cemetery.html.

Vrabel, Jim. A People’s History of the New Boston. Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press, 2014. [F73.52 .V73 2014]

Wakefield, Mary M. B. "The Boston Public Garden, Showcase of the City." Arnoldia 48, no. 3 (1988): 32-47. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42955609.

Zaitzevsky, Cynthia. Frederick Law Olmsted and the Boston Park System. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1982. [SB483.B73 Z34 1982]

Zaitzevsky, Cynthia and Boston Redevelopment Authority. Final Report: Architectural and Historic Surveys of Park Square, Jamaica Plain, Forest Hills Cemetery, Olmsted Park System and Pierce Square, Dorchester, Lower Mills. 1970. Accessed February 21, 2018. https://archive.org/details/finalreportarchi01zait.

Credits

Curator

Dory Klein, Map Librarian

Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center Staff

Connie Chin, President

Lynn Brown, Education and Outreach Coordinator

Lauren Chen, Reference and Cataloging Librarian

Alison Cody, Development Manager

Ronald Grim, Curator of Maps

Michelle LeBlanc, Director of Education

Education materials created by:

Michelle LeBlanc, Director of Education

Lynn Brown, Education and Outreach Coordinator

Interactive displays and digital maps created by:

Peter Hutt-Sierra, Cartographic Project Assistant

NBBJ

The Trust for Public Land

Framing and Matting

Andrew Leonard

Boston Public Library Staff

Communications Department

Digital Services

Facilities Department

IT Department

Research Services

Graphic Design and Production

Neva Corbo-Hudak Graphic Design

The Market King

Lenders

The University Archives and Special Collections Department, Joseph P. Healey Library, University of Massachusetts Boston

Special Thanks

Alan Auger, Creative Manager, Rose Kennedy Greenway Conservancy

Adrian Benepe, Senior Vice President and Director of City Park Development, The Trust for Public Land

Jesse Brackenbury, Executive Director, Rose Kennedy Greenway Conservancy

Evan Bradley, Marketing and Communications Coordinator, Emerald Necklace Conservancy

Patricia L. Bruttomesso, Archival Collections Project Manager, The University Archives and Special Collections Department, Joseph P. Healey Library, University of Massachusetts Boston

Derek Cascio, Asst. Professor of Industrial Design, Wentworth Institute of Technology; Co-founder Design Museum Boston

Chris Cook, Commissioner, Boston Parks and Recreation Department

Margaret Dyson, Director of Historic Parks, Boston Parks and Recreation Department

Kevin Essington, Director, Southern New England Area, The Trust for Public Land

Louisa Gag, Program Coordinator, LivableStreets Alliance

Fran Gershwin, Chair, Maintenance and Management Oversight Committee, Muddy River Restoration Project

Spencer Grant, freelance photographer

Liz Holbrook, Consulting Registrar, Museum & Collector Resource

Christina Kim, Boston Planning & Development Agency

Gavin Kleespies, Director of Programs, Massachusetts Historical Society

Charles Kozlowski, ASLA, Vice President, Principal, Halvorson Design Partnership, Inc.

Tony Lechuga, Program Manager, LivableStreets Alliance

Karen Mauney-Brodek, President, Emerald Necklace Conservancy

Charlie McCabe, Director, Center for City Park Excellence, The Trust For Public Land

Jen Mergel, Curator

Pamela C. Messenger, General Manager, Friends of Post Office Square

Keith N. Morgan, FSAH, Professor Emeritus, History of Art & Architecture and American & New England Studies, Boston University

Jason Ruggiero, Assistant Manager, Urban and Community Affairs, Massachusetts Port Authority

Veronika Trufanova, Director of Development and External Relations, Emerald Necklace Conservancy

Natalia Urtubey, Executive Director, Imagine Boston 2030

Renata Von Tscharner, President, Charles River Conservancy

Philip Weiser, State Director of Philanthropy, Massachusetts & Rhode Island, The Trust for Public Land

Laurie Zapalac, Tour Leader, Friends of the Boston Harborwalk

Community Partners

Arnold Arboretum· Boston Harbor Now Boston Map Society· Boston Parks and Recreation Department· Boston Planning & Development Agency Brookline Parks and Open Space· Charles River Alliance Charles River Conservancy· Charles River Watershed Association· Emerald Necklace Conservancy· Environmental League of Massachusetts· Esplanade Association Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site· The Freedom Trail Foundation · Friends of Post Office Square· Friends of the Public Garden· Imagine Boston 2030· Livable Streets Alliance ·Department of Conservation and Recreation – State Parks· Massachusetts Historical Society· Massachusetts Port Authority· Mount Auburn Cemetery· Muddy River Restoration Project Maintenance and Management Oversight Committee ·Rose Kennedy Greenway Conservancy ·Sasaki ·The Trust for Public Land · Trustees ·University of Massachusetts Boston Archives and Special Collections Department

Press

Tracing the Growth of Green Space in Boston

Boston Globe, March 29, 2018