Introduction

When reading maps, we expect map makers to use standard conventions, especially in regard to map projection or composition, orientation, scale, and symbols. When a map maker does not use generally-accepted practices, we ask why? What is the story the map maker is trying to tell?

The maps displayed here highlight a variety of unconventional maps spanning the history of the printed map. For each, we demonstrate how it defies convention, and how that particular cartographic design heightens its story.

1. Orientation and Perspective

Andreas Cellarius (fl. 1656-1702)

“Coeli Stellati Christiani Hæmisphærum Prius,” in Harmonia Macrocosmica…

Amsterdam, 1661

While most Renaissance and Baroque geographers mapped the Earth, a few directed their attention to the skies. They observed and mapped the heavenly bodies and theorized about their relationship to the Earth. This increased astronomical knowledge was recorded in a lavish celestial atlas, illustrated with beautifully engraved and hand-colored plates.

Chapters of this treatise describe the magnitude of the stars, various lunar and solar theories, the nature of the planets, and the celestial constellations. In contrast to the generally accepted practice of depicting constellations as classical mythological figures, this plate reconfigures them from a Christian perspective.

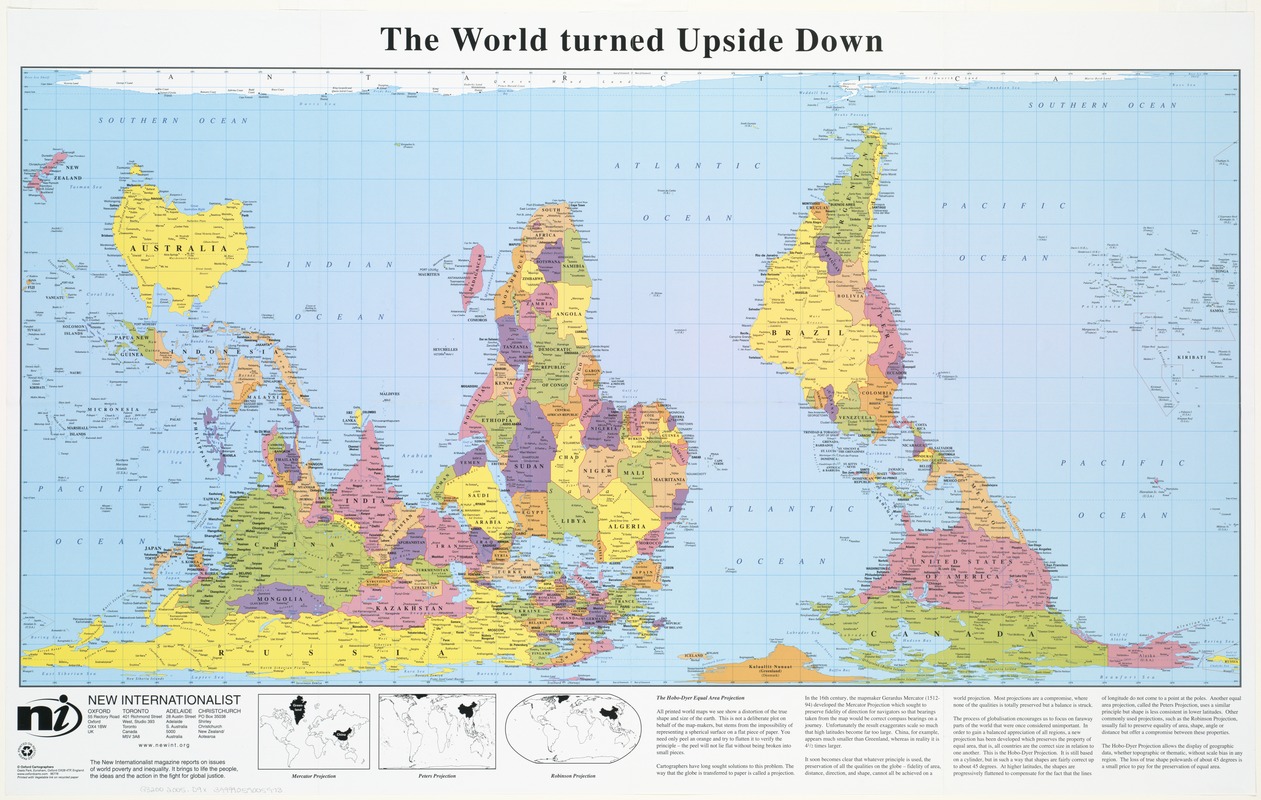

New Internationalist Publications

The World Turned Upside Down

Oxford and Amherst, MA: Oxford Cartographers and ODT, Inc., 2005

Oriented with South at the top, this “upside-down” world map presents a disconcerting image, but clearly conveys a message that unconventional world views can be meaningful. Prepared for an organization that reports on global poverty and inequality, the map helps to teach “people to see the world from a broader, more inclusive perspective.”

Traditional, north-oriented world maps emphasize Europe and North America, implying that other continents are less important. This contrary perspective places Africa and South America in the center, suggesting that the southern hemisphere’s developing countries are equally important.

Giacomo Gastaldi (ca. 1500-1560)

“Prima Tavola,” from Giovani Battista Ramusio, Delle Navigationi et Viaggi

Venice, 1554

Courtesy Afriterra Foundation

Twentieth century, socially-oriented geographers were not the first to turn the world upside down. For example, Venetian geographer Ramusio included this south-oriented map of Africa in his mid-16th century collection of exploration and travel accounts.

Since the Republic of Venice, a world power of commerce and trade, had strong economic ties with the Ottoman Empire, this orientation most likely reflected the Islamic cartographic tradition in which maps were often oriented with South at the top of the map. The geographic content of the map is based on knowledge obtained from Arab geographers and Portuguese discoveries.

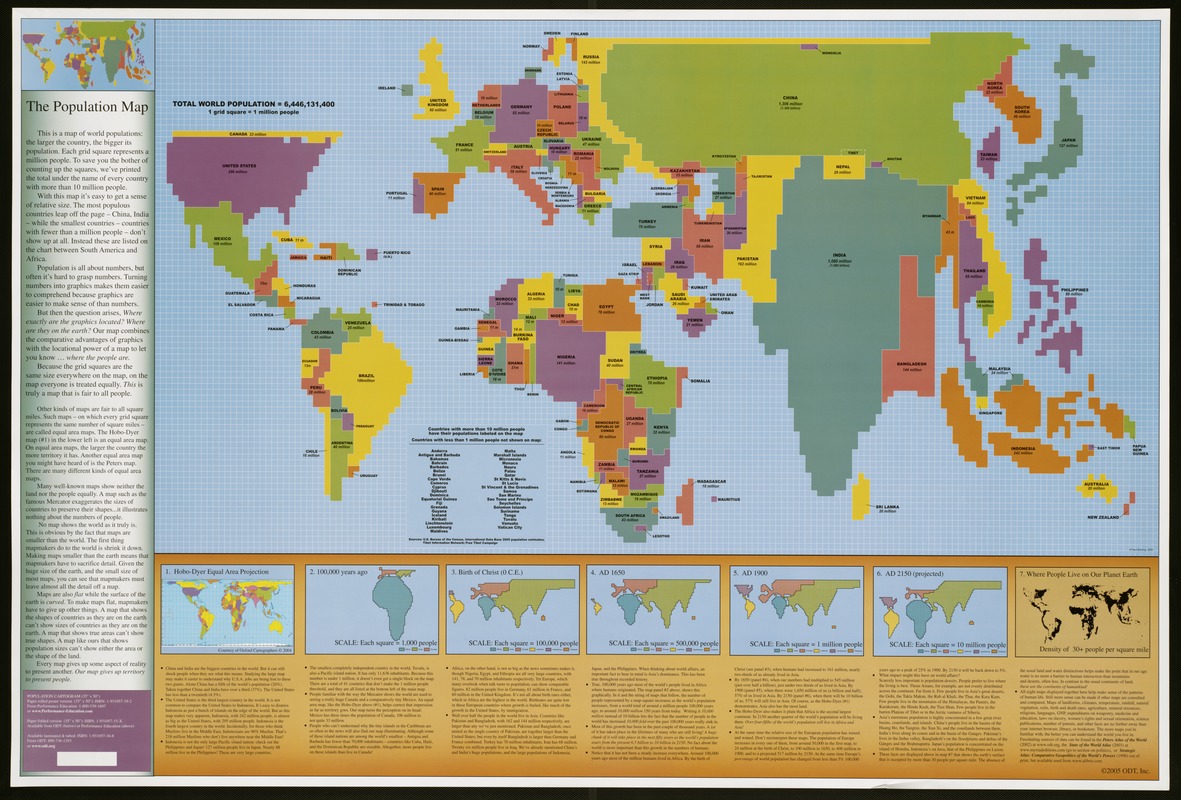

ODT, Inc.

The Population Map

Amherst, MA, 2003

This strange “lego”- like map is known as a cartogram, a diagram combining map and graph qualities. It distorts the size and shape of countries to portray their population (number of people) rather than their geographic territory (number of square miles).

Since this is a map about people, it has a totally different appearance than conventional maps. China and India occupy the most space because they have the largest populations. On the other hand, Russian Siberia and Canada, which cover large expanses of geographic territory, have much smaller populations and appear as narrow linear strips.

Heinrich Bünting (1545-1606)

“Die gantze Welt in ein Kleberblat …,” from Itinerarium Sacrae Scriptura …

Magdeburg, 1581

Courtesy Mapping Boston Foundation

Using a cloverleaf to depict the world, this cartographic curiosity reflects the traditional Medieval world view, with each leaf representing one of the three continents — Asia, Europe, and Africa. Jerusalem is clearly marked at their intersection.

This Venn-like diagram was one of several whimsical diagrams included in a book, which was essentially the Bible rewritten as an illustrated travel book. The author, a professor of theology in Hannover, Germany, used the trefoil or cloverleaf coat of arms of his native city to represent the world, making this map more a statement of civic pride than a serious attempt at cartography.

2. Views

Charles R. Parsons (1821-1910) and Lyman W. Atwater (1835-1891)

The City of Boston

New York: Currier & Ives, 1873

Bird’s-eye or perspective views as imagined from 2,000-3,000 feet provided a popular format for depicting American cities during the last half of the 19th century. Boston was documented in forty such views, but north, the generally accepted orientation for maps, was rarely at the top.

These views depicted the city from all around the peninsula, with each emphasizing a different aspect of the city’s geography. This colorful example, viewing the city from the northeast, placed the waterfront with numerous ships, wharves, and warehouses in the foreground. This vantage point emphasized the importance of maritime trade to the city’s economy.

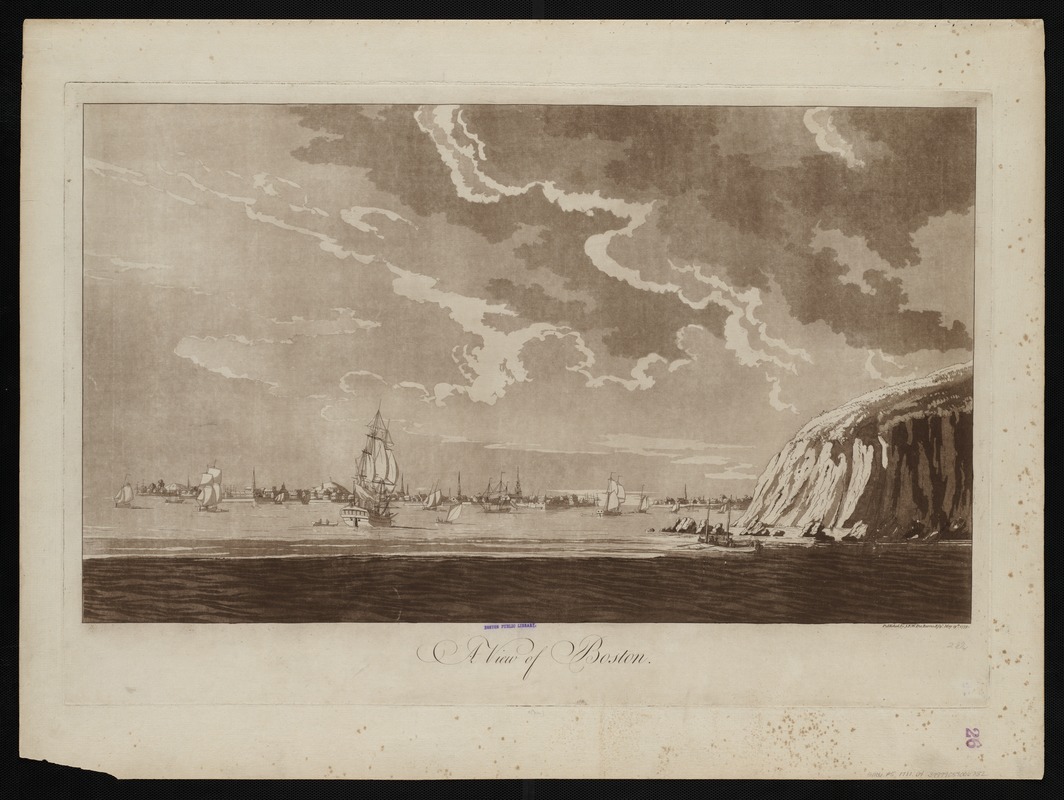

Joseph F.W. Des Barres (ca. 1729-1827)

“A View of Boston,” from The Atlantic Neptune

London, 1779

Viewing Boston from the ocean was not a novel concept originated by 19th century bird’s eye view artists. This Revolutionary War era landscape scene, published with a collection of nautical charts, depicted Boston Harbor as it would have appeared to approaching ships.

While not technically a map or chart, coastal and headland views were also considered navigational aids. Such graphic images assisted ship captains in identifying prominent landmarks as they entered the harbor. Clearly visible on Boston’s late 18th century skyline are numerous church spires and a flag on Beacon Hill.

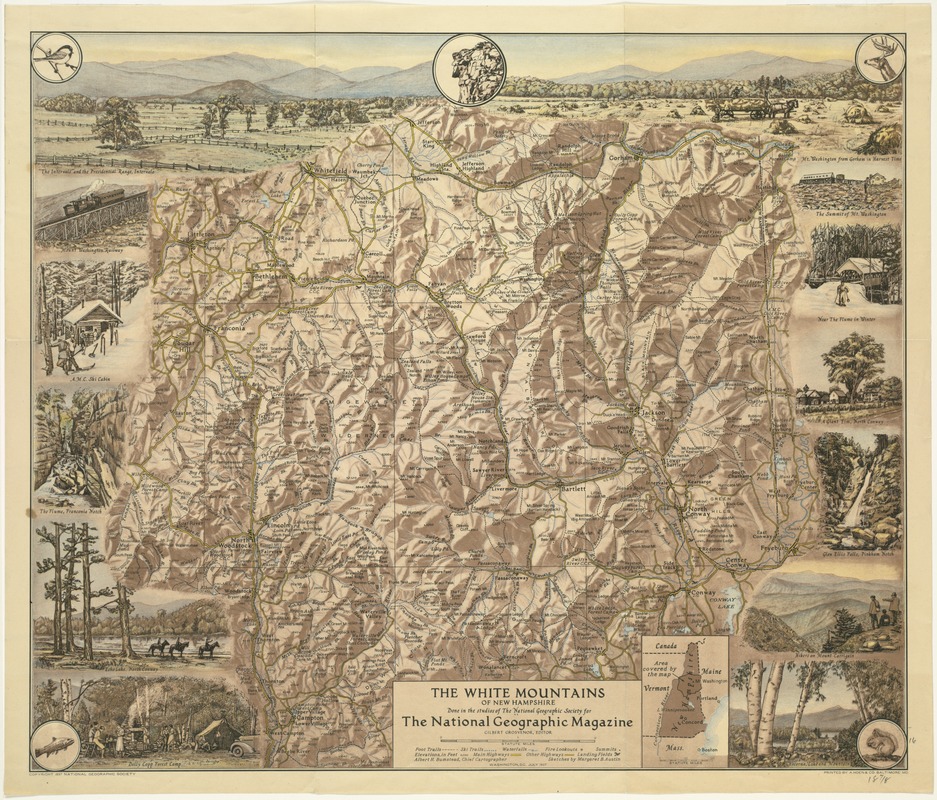

National Geographic Society

The White Mountains of New Hampshire

Washington, DC, July 1937

A challenge for map makers has been the representation of topography or physical relief. Several methods that were practiced widely during the 19th and 20th centuries and have become generally accepted as standard conventions utilize short hachure marks, contour lines, and shading.

The later technique, which is the most visually attractive, is illustrated with this National Geographic map of New Hampshire’s White Mountains. Marginal vignettes also help readers appreciate this mountainous landscape. Three very unusual and creative examples of White Mountain maps, which are displayed here, demonstrate the drama of depicting the physical terrain.

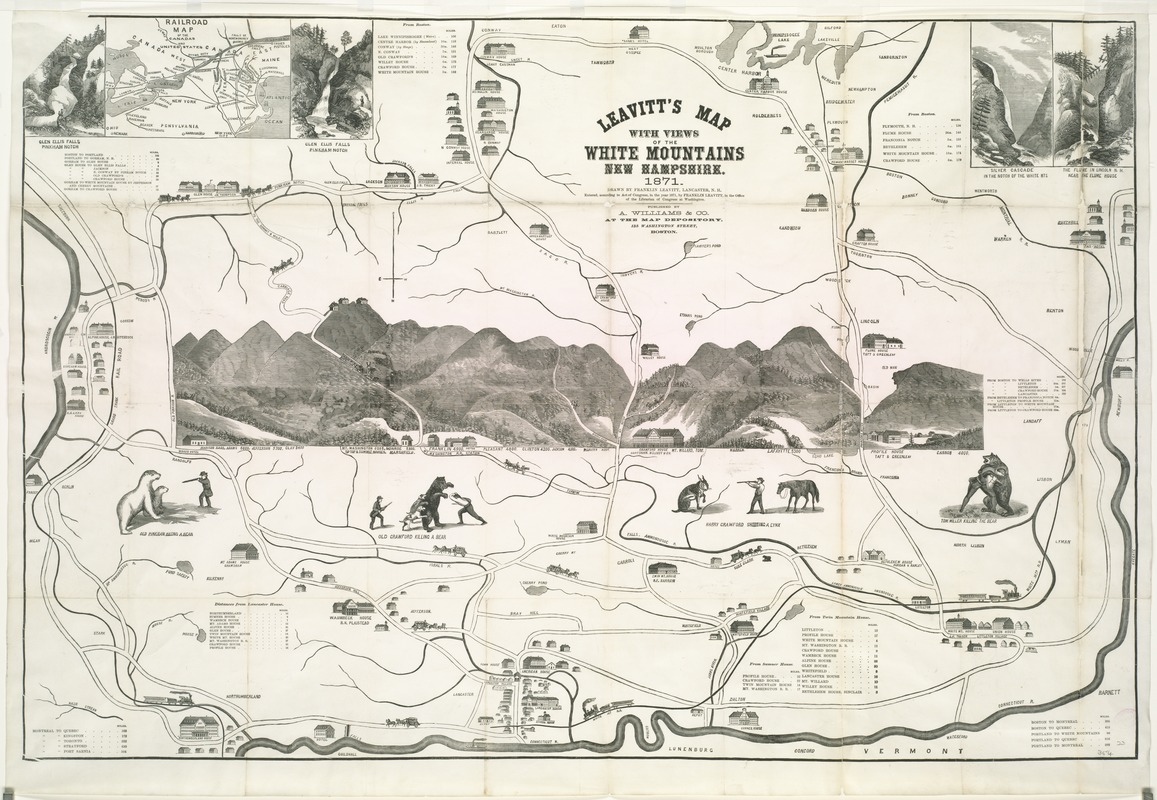

Franklin Leavitt,

Leavitt’s map with views of the White Mountains

New Hampshire, 1871

Combining folk art with a schematic tourist map, this unusual map views the White Mountains from the northwest. In the center, the mountains were drawn in landscape format surrounded by curious vignettes including “Old Crawford Killing a Bear” and “Harry Crawford Killing a Lynx”. Along the top are a railroad map and views of waterfalls, while symbolic images of hotels, stage coaches, and trains alert readers to the region’s tourist amenities.

Leavitt, a laborer, mountain guide, and self-taught mapmaker, created this pictorial map. Reflecting his regional bias, he located Lancaster, his hometown, and the Connecticut River in the center foreground.

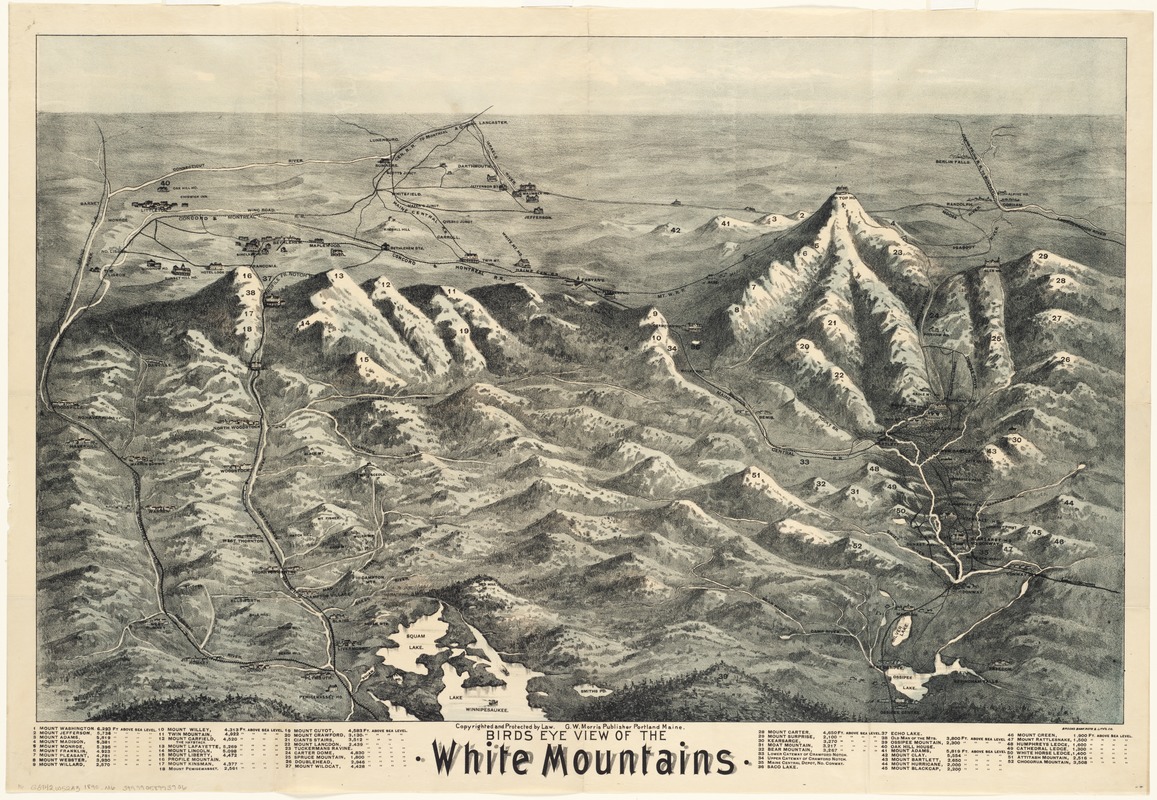

G. W. Morris (fl. 1886-1890)

Bird’s Eye View of the White Mountains

Portland, ME, 1890

Looking north from Lake Winnipesaukee toward the White Mountains, this bird’s eye view provides an aerial perspective of the northern part of New Hampshire. Bird’s eye views, which were very popular for depicting cities and towns during the last half of the 19th century, were also used to advertise popular tourist destinations.

In this rendition of the White Mountains, the most important peaks were emphasized with their elevations intentionally exaggerated. These mountains were numbered, with a legend listing names and elevations above sea level. Pictorial symbols identify hotels, resort communities, and railroads, providing further information for prospective tourists.

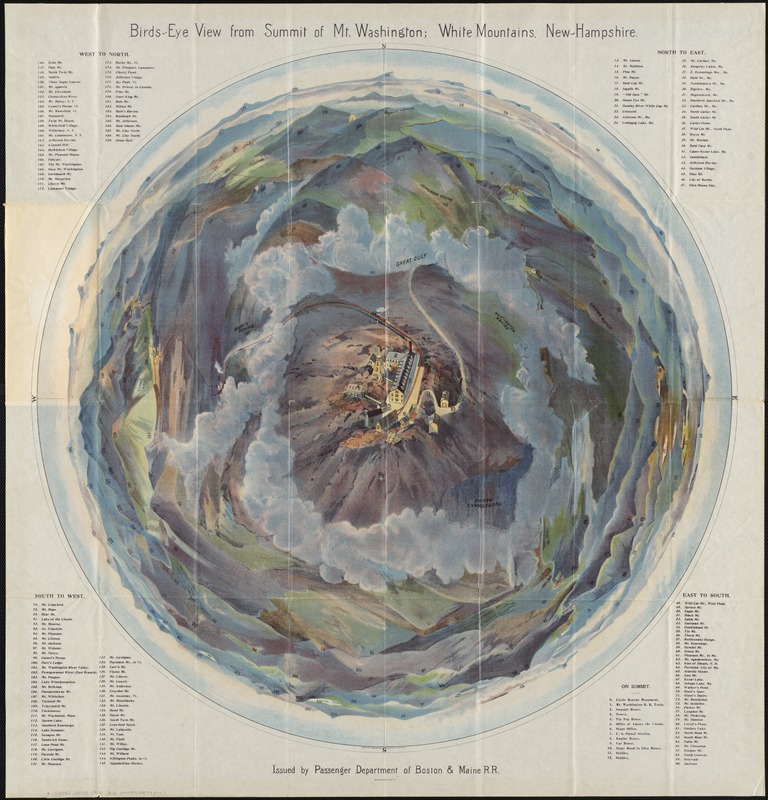

Boston and Maine Railroad, Passenger Department

Bird’s Eye View from the Summit of Mt. Washington, New Hampshire

Boston, 1902

Although entitled a bird’s-eye view, this colorful presentation provides a fish-eye or 360-degree panoramic perspective. It distorts the topography of Mount Washington from a single vantage point directly above the mountain.

The mountain’s summit, with accurately delineated buildings and the approaching road and railroad, is the central focus. Everything else is distorted. The surrounding mountains appear in the distance as non-distinctive colored hills, but each is numbered and identified in corresponding lists in the map’s four corners. Published by the Boston and Maine Railroad, this artistic piece would certainly appeal to tourists visiting New England’s tallest landmark.

3. Pictorial Maps

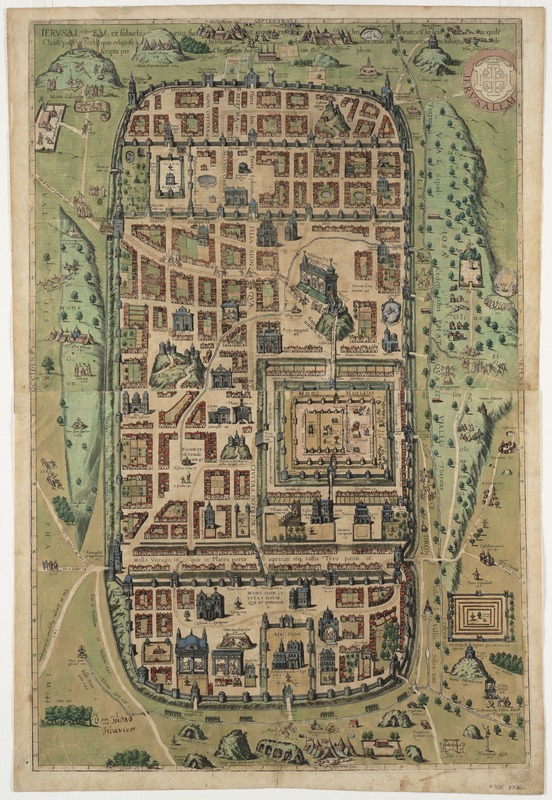

Christiaan van Adrichem (1533 – 1585)

“Jerusalem, et suburbia eius . . . ,” from Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg, Civitates Orbis Terrarum

Cologne, 1572 – 1617

Illustrations of ships and monsters adorn many early maps, often filling the empty spaces of unexplored territories. However, this map of Jerusalem published in the late 16th century used pictorial elements as symbols to help convey the map’s message.

Compiled by a Dutch theologian, this historical map reportedly recreates Jerusalem at the time of Christ. Many buildings were depicted as 16th century European structures, with their facades placed adjacent to the streets rather than drawn in perspective. In addition, there are 270 numbered and captioned scenes, showing sites or events mentioned in the Old and New Testaments.

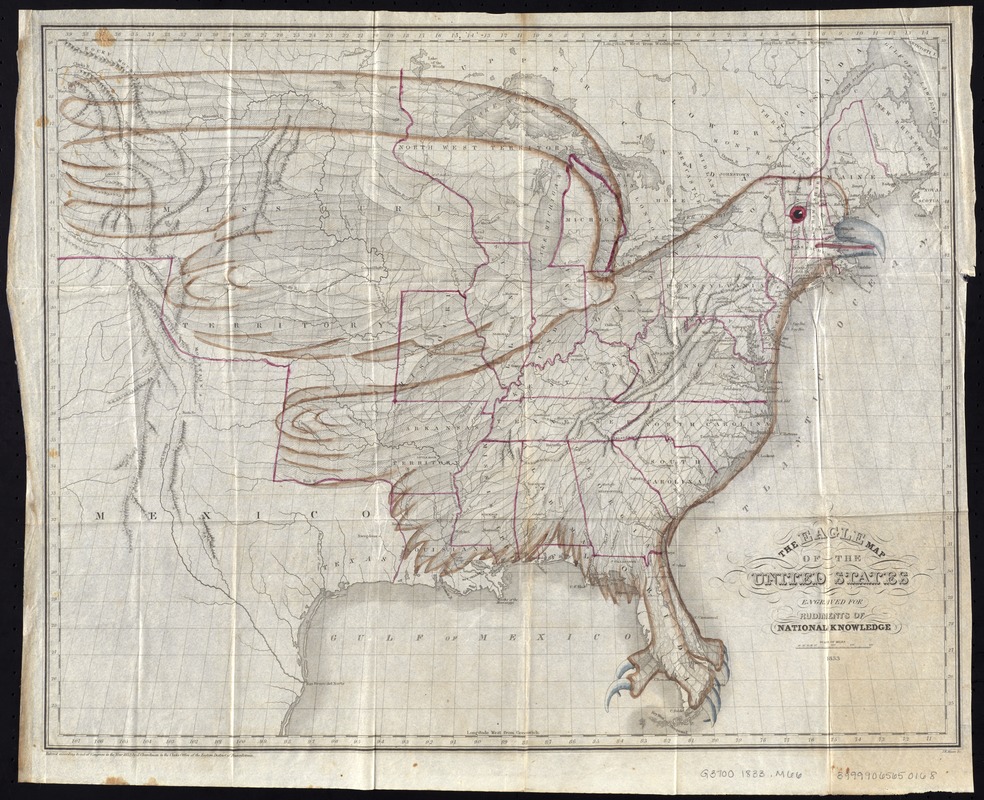

Joseph Churchman (1767-1837)

“The Eagle Map of the United States,” from Rudiments of National Knowledge, Presented to the Youth of the United States

Philadelphia, 1833

In this unusual map, one pictorial image — an eagle — was superimposed on a map of the United States. The author of the accompanying geography book stated that the map was designed to serve as a memory device for young students learning the country’s geography and history. He explained that the eagle was selected for its visual and iconic appeal.

The author also made the point that secession could disfigure this national icon, suggesting that the map was intended to promote unity at a time when political debates about tariffs, slavery, and states’ rights were part of the national discourse.

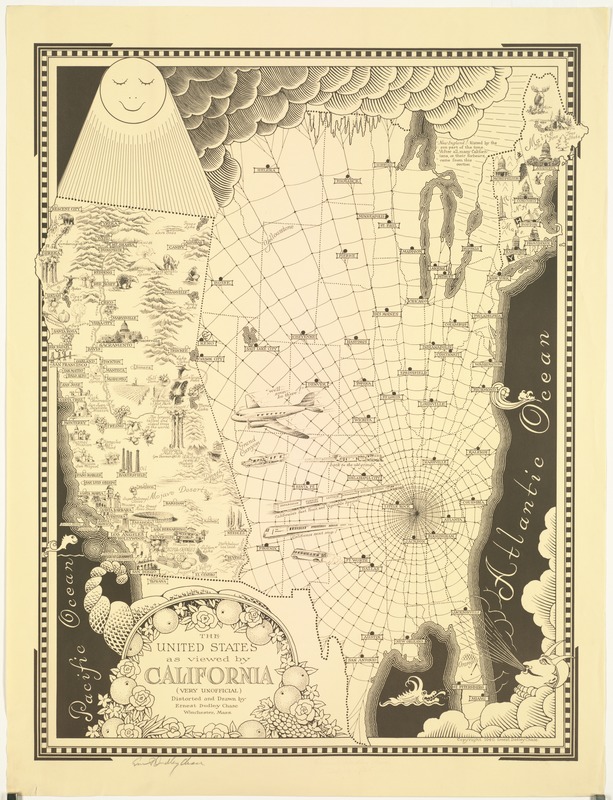

Ernest Dudley Chase (1878-1966)

The United States as Viewed by California (very unofficial)

Winchester, MA, 1940

Recognized for his whimsical pictorial maps, Chase created this highly distorted view of the United States as perceived by Californians. One-third the size of the rest of the country, the state is perpetually drenched by the sun. A bustling California is also depicted as a cornucopia of plenty, teaming with industry, agriculture, recreational activity, and natural wonders.

The rest of the county is overshadowed by a dark cloud and a vast, depressing spider web. Other states are distorted or are omitted entirely. However, Chase’s native New England retains its shape and receives some sunlight for half of the year.

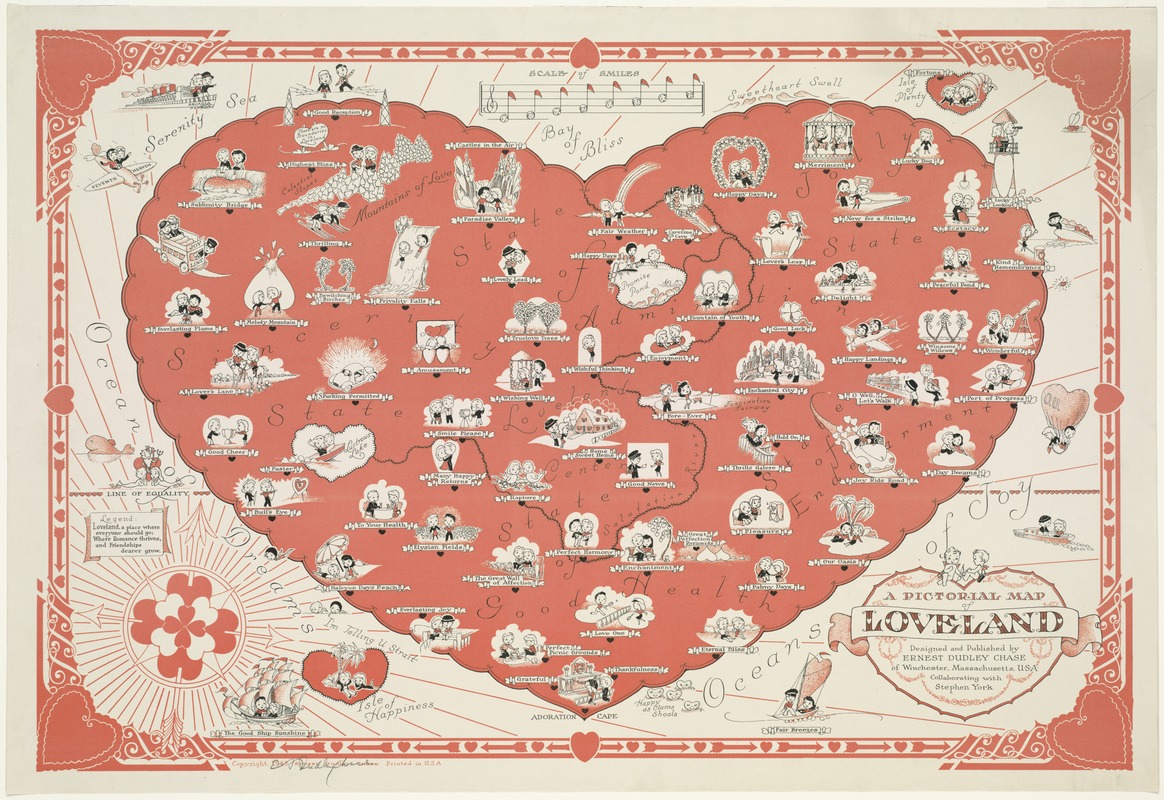

Ernest Dudley Chase and Stephen York.

A Pictorial Map of Loveland

Winchester, MA, 1943

During his career as a greeting card designer, Chase published approximately fifty pictorial maps, generally displaying a sense of humor. While most used illustrations to highlight geographical information in real places, he also created maps of imaginary places.

This fictitious map of a heart-shaped place called Loveland merged the sentimentality of greeting cards with standard cartographic conventions. Loveland was appropriately portrayed with meticulously drawn and cleverly labeled images. From its decorative border to conventional map elements, Chase completely committed to the theme of love. Even the compass rose was composed of a cluster of hearts pieced by three arrows.

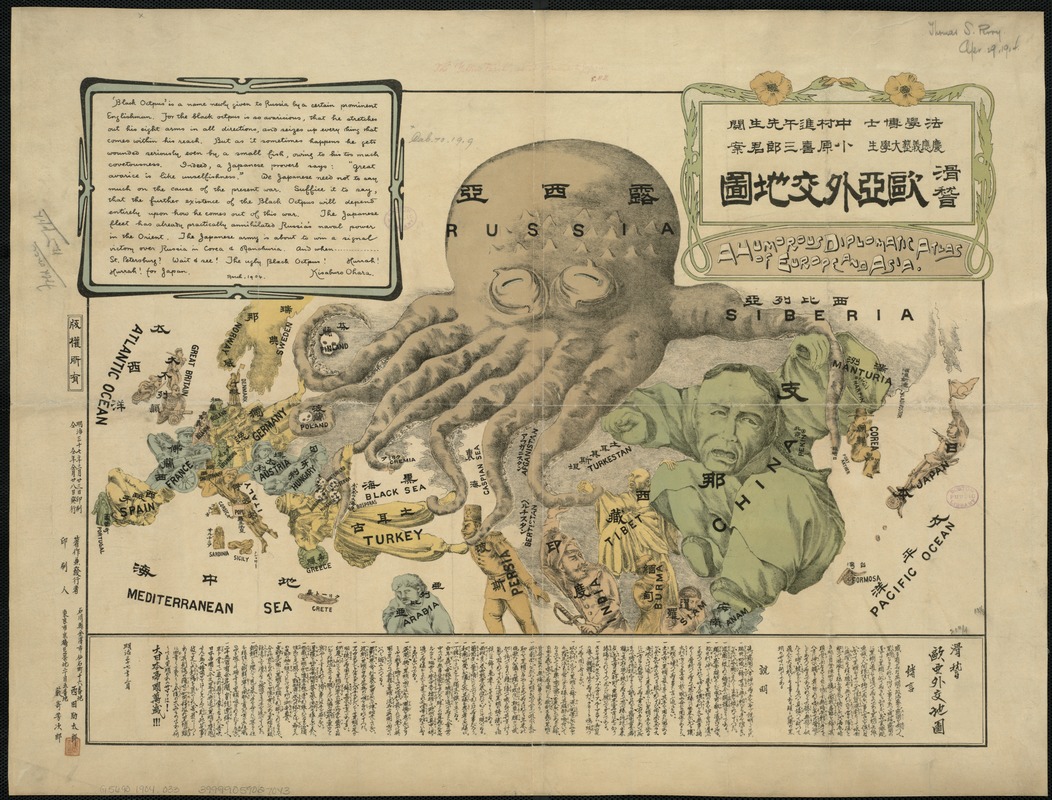

Kisaburo Ohara

A Humorous Diplomatic Atlas of Europe and Asia

Tokyo, 1904

Created during the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) by a student at Keio University, this propaganda map presents a negative image of the Russian Empire. It is depicted as an over reaching “black octopus” extending its tentacles throughout Europe and Asia, with the other countries represented as human figures. Some countries like China thwart the attack, while others, including Persia and Tibet, are firmly in its grasp.

Labeled in both Japanese and English, the map is definitely pro-Japanese. The author portrays Japan as a battle-ready soldier facing the octopus with a gun in one hand and a flag in the other.

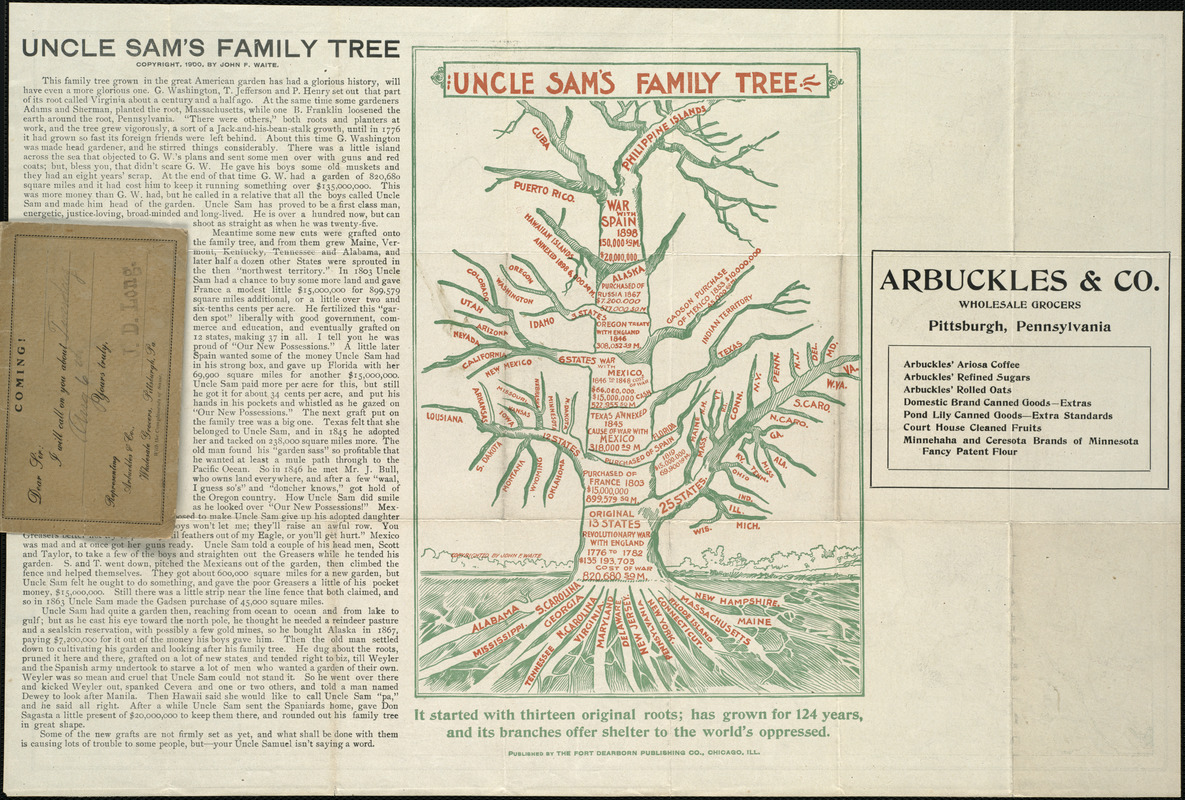

John F. Waite (fl. 1894-1900)

Uncle Sam’s Family Tree

Chicago, 1900

Created as an advertisement for Arbuckles, a wholesale grocer, the territorial growth of the United States is compared to an orchard tree. Printed on the verso of a United States map, this unusual graphic is essentially a geographical time line, charting the chronological growth of the nation.

In representing the United States, the cartographer uses a tree that sits in “the great American garden” and is tended by the mythical figure Uncle Sam. The roots symbolize the original thirteen colonies, while subsequent “grafts” and branches represent other states added by war, purchase, and annexation.

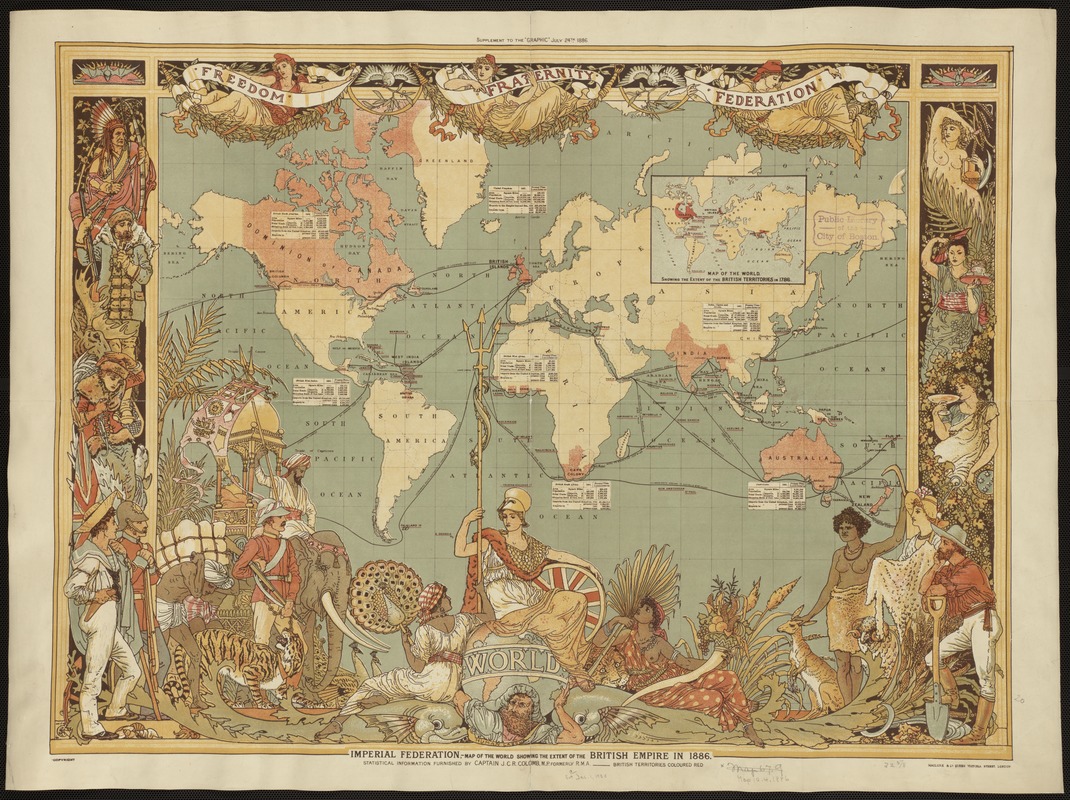

Maclure & Co.

Imperial Federation, Map of the World Showing the Extent of the British Empire in 1886

London, Supplement to The Graphic, July 24, 1886

Published for a British weekly illustrated newspaper, everything about the design of this elaborately decorated world map glorifies the late-19th-century British Empire. It used a Mercator projection centered on the Greenwich Prime Meridian, placing Great Britain just above the map’s central focal point.

All of the British colonies spreading out to the east and the west were highlighted with red, while other geographical areas were left blank, virtually without place names. The words “Freedom, Fraternity, Federation,” suggesting a peaceful co-existence within the British Empire, were prominently placed along the map’s top margin, but the remainder of the map’s illustrations loudly proclaim “colonialism.”

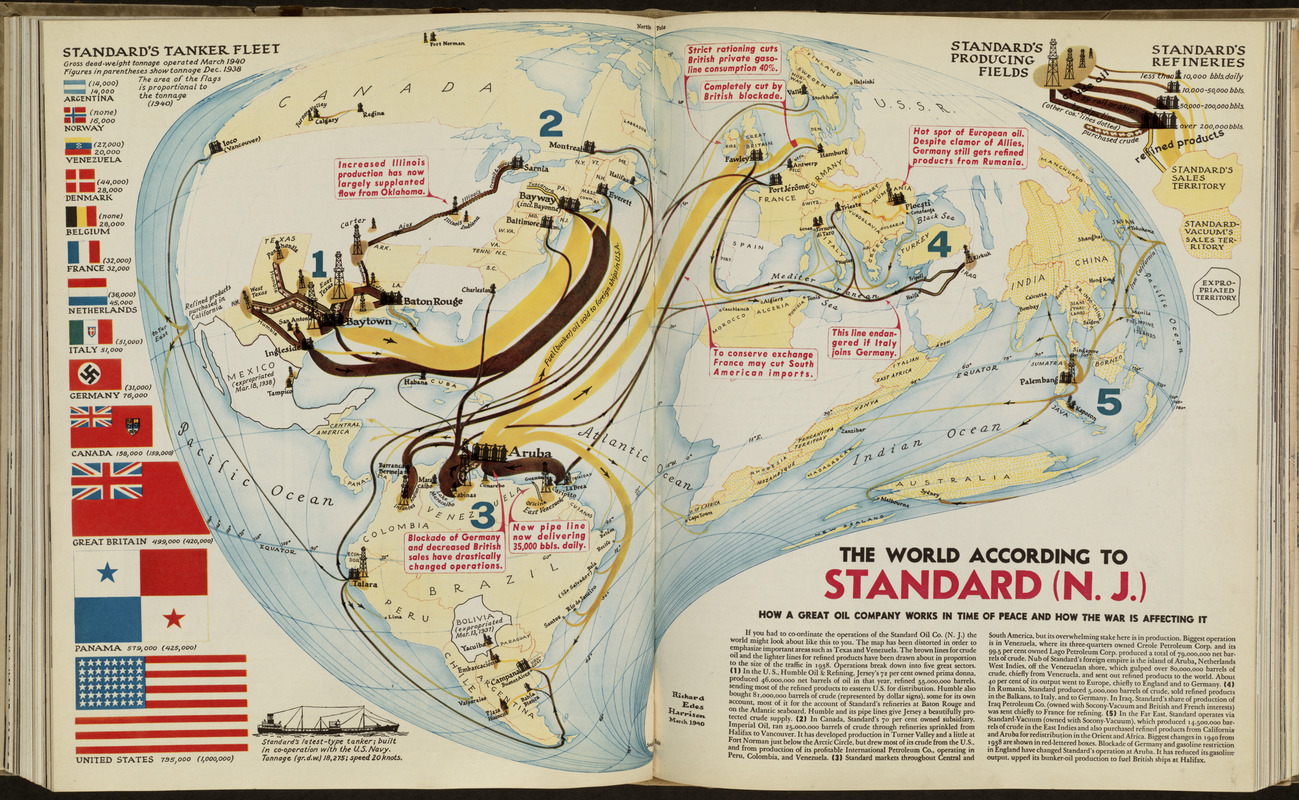

Richard Edes Harrison (1901-1994)

“The World According to Standard (N.J.)" in Fortune 21, no. 5

May 1940

This obviously distorted world map was prepared by freelance cartographer Richard Harrison to illustrate a magazine article discussing Standard Oil Company’s international operations at the beginning of World War II. Recognized for his innovative solutions in cartographic design, Harrison invented an “oil drop” world projection, which emphasized Texas and Venezuela, Standard Oil’s major areas of crude oil production.

Combined with creative symbols, he illustrated the complexity of the company’s operations. Pictorial symbols (oil derricks and refineries), drawn in various sizes, identified areas of oil production. Proportional flow lines traced the movement of crude and refined oil by pipeline or tanker.

4. Projections

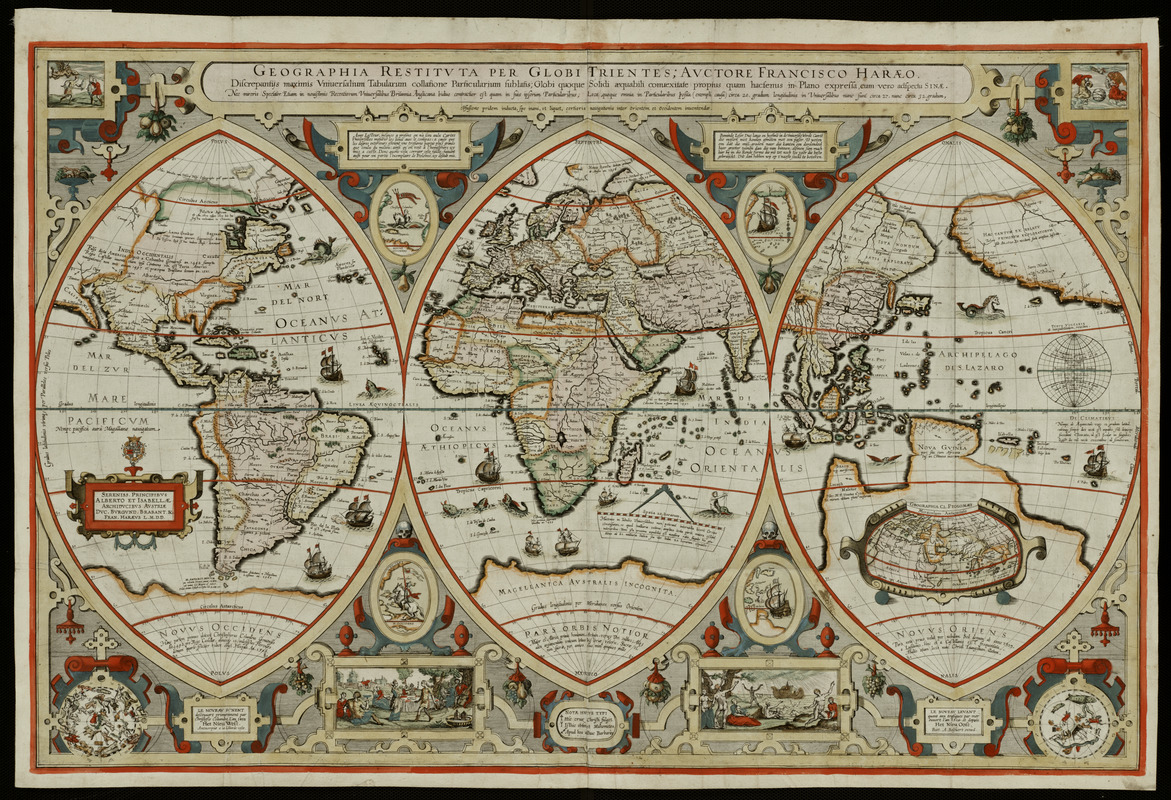

Franciscus Verhaer (c. 1555-1631)

Geographica Restituta per Globi Trientes …

Amsterdam, c. 1618

Courtesy Mapping Boston Foundation

Portraying the world on a triptych or three-part projection was very uncommon during the Golden Age of Dutch cartography. Such a format, however, was commonly used in altarpieces and would have been familiar to a 17th-century Christian audience.

This design reflects Verhaer’s training as a theologian and classical historian. The central section encompasses the Old World – Europe, Africa, and western Asia, with Jerusalem serving as the focal point. The left section displays European discoveries to the west (Novus Occidens), while the right depicts discoveries to the east (Novus Oriens). The rich decorative elements illustrate religious and exploration themes.

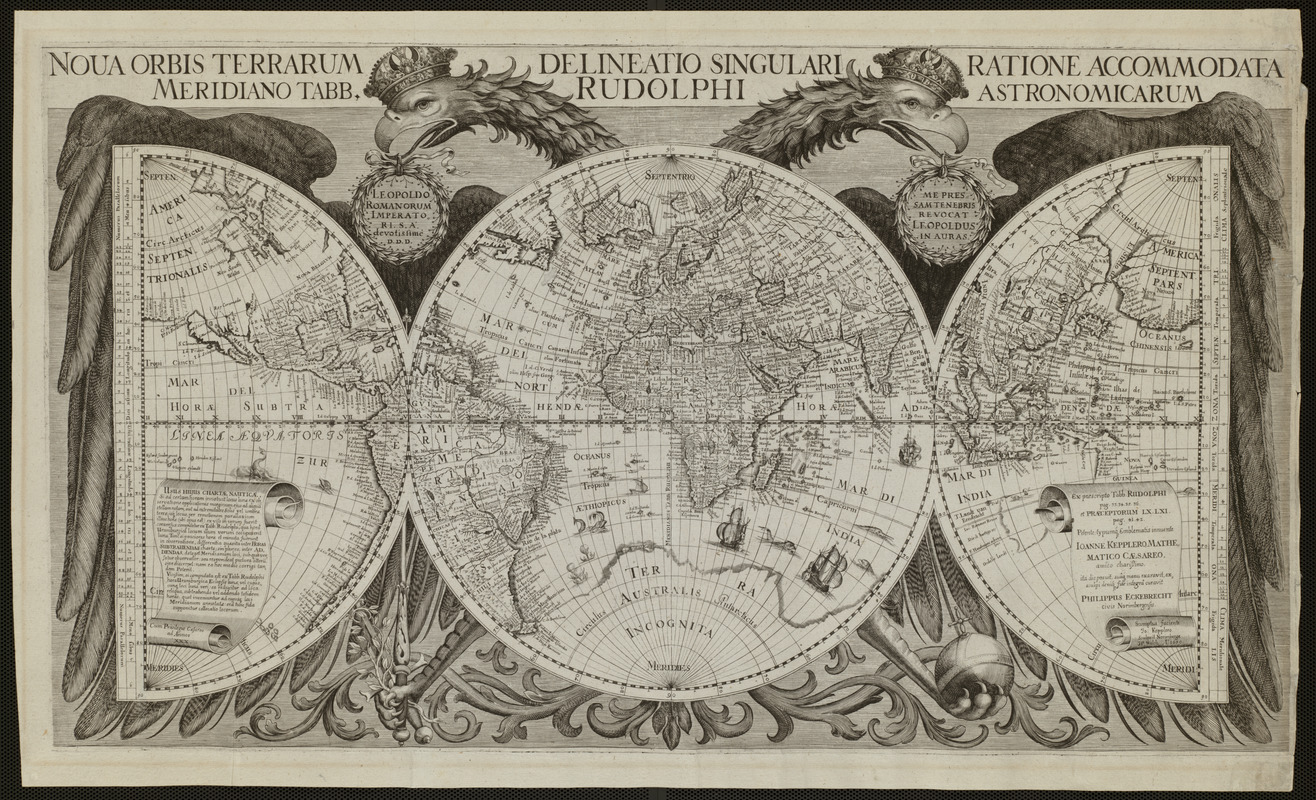

Philip Eckebrecht (1595-1677)

Nova Orbis Terrarum Delineatio Singulari Ratione Accommodata Meridiano Tabb. Rudolphi Astronomicarum

[Ulm, after 1658]

In this striking image, the world is portrayed on one full circle (or hemisphere), flanked by two half circles. This unusual geometrical configuration is embraced by a double-headed eagle, an emblem associated with the Holy Roman Empire.

The map was prepared as an illustration for astronomer Johannes Kepler’s published astronomical tables. Implying a strong scientific basis, the map also makes a statement about politics and patronage. The central sphere focusing on Europe, is superimposed on the eagle’s body, while the eagle’s wings embrace the entire world, suggesting the wide extent of the empire to the east and west.

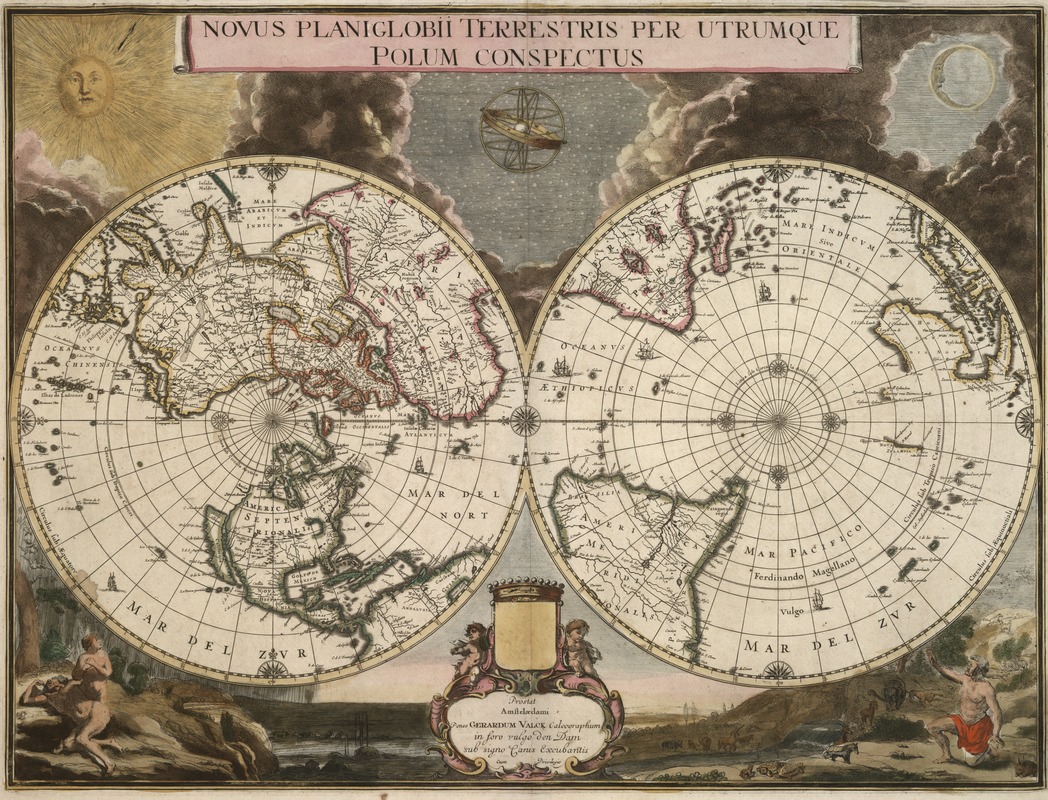

Gerard Valck (1652-1726) after Joan Blaeu (c. 1599-1673)

Novus Planiglobii Terrestris per Utrumque Polum Conspectus

Amsterdam, [c.1695]

While most double hemisphere maps display the world divided into eastern and western hemispheres, a more unusual portrayal uses the northern and southern hemispheres. Gerard Valck’s ornately decorated map exemplifies a polar-oriented projection.

The two spheres, adorned with ships and a symmetrical arrangement of compass roses, are set against an artistic backdrop highlighting the Genesis story of creation. At the top is a dramatic presentation of the sun, moon, and stars emerging from clouds of darkness. Other vignettes depict Adam and Eve leaving the Garden of Eden, and Noah selecting pairs of animals for the ark.

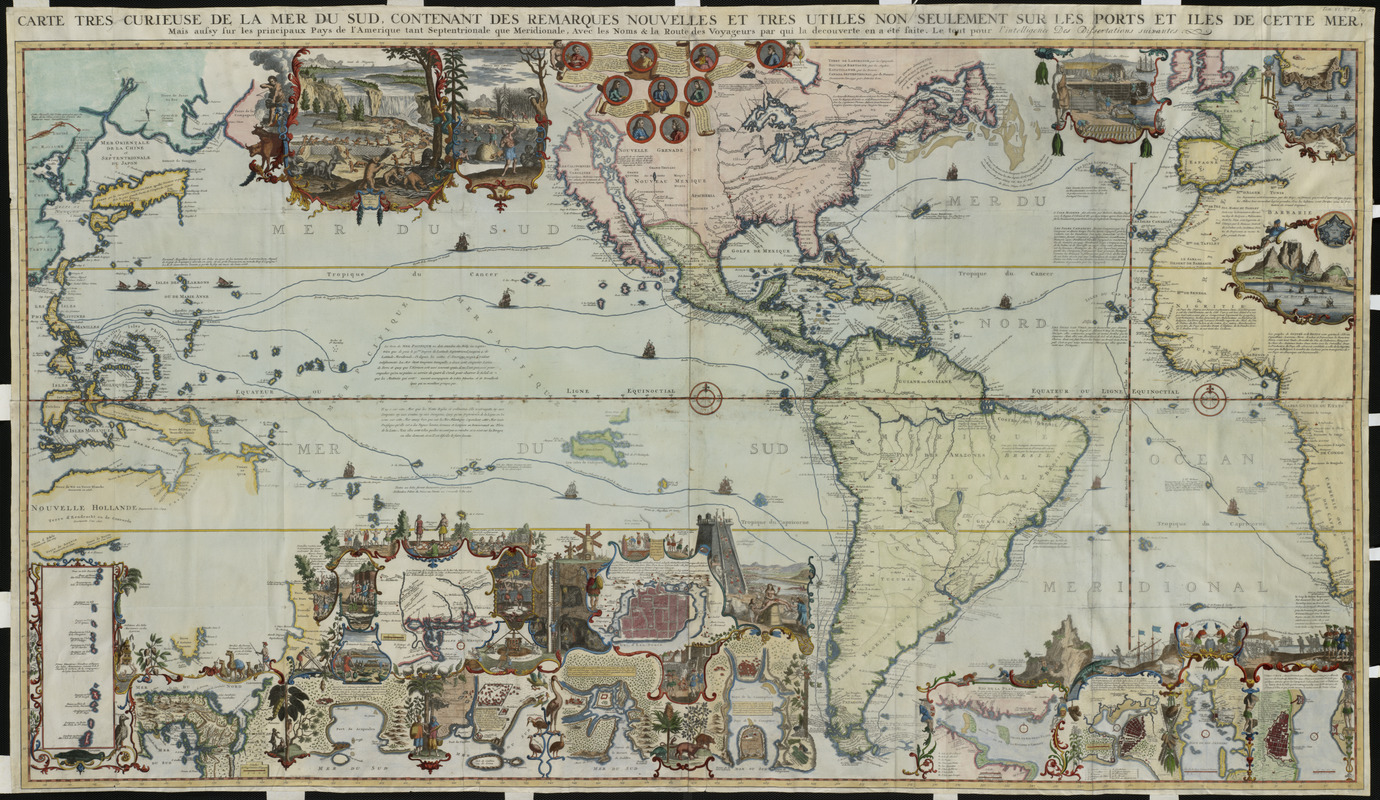

Henri Abraham Châtelain (1684-1743)

Carte très curieuse de la Mer du Sud …mais aussy sur les principaux Pays de l’Amerique tant Septentrionale que Meridionale …

Amsterdam, 1719

The central focus of most pre-18th century maps was the Old World and Atlantic Ocean, but this richly decorated map emphasized the Americas and the Pacific Ocean. Appearing in an encyclopedic, seven-volume work entitled Atlas Historique, it was a celebration of the age of discovery and New World geography.

With more than 35 insets and vignettes, it illustrates such important explorers as Columbus, Vespucci, Magellan, and Drake, as well as colonial economies based on beaver, cod, and sugar. Several large-scale maps portray significant locations, such as the Mississippi Delta and Niagara Falls, as well as numerous cities and towns.

Credits

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center Staff

Debra Block, Director of Education

Lauren Chen, Cataloger

Stephanie Cyr, Senior Cataloger

Ronald Grim, Curator of Maps

Janet Spitz, Executive Director

Evan Thornberry, Reference and Preservation Librarian

Catherine Wood, Office Manager