Introduction

American schoolchildren have studied geography since the late 18th century. Traditionally viewed as an essential subject for boys’ and girls’ education, geography was taught to children in primary school, and to young adults studying in high school and college settings. In this display of forty maps, globes, games, atlases and related objects, we see the evolution of geographic education, examine the visual aids used by teachers in the classroom, and marvel at unique student-produced geography projects from the late 18th to the 20th centuries.

1. Models

Trippensee Planetarium Company

The Trippensee Planetarium

Detroit, MI, 1908-25.

The celestial model displayed here, referred to as an orrery, was used as an educational tool to demonstrate the movements of the Earth, moon and Venus relative to one another and the sun. Invented in England in 1713, orreries were originally available only to the very wealthy; however, they gradually became more affordable and were used as visual aids in classrooms. Astronomy was closely linked to geographic education at the time, and would have been the first subject studied in geography textbooks of the 18th and 19th centuries. This orrery was produced in Detroit, Michigan in the early 20th century, and similar models are still manufactured today.

Ellen Eliza Fitz

Fitz Globe

Boston, [1879]

This classroom globe was published in Boston by the textbook firm of Ginn and Heath. The mounting system, with two vertical rings showing the changing daylight, twilight and nighttime hours any place on the Earth, was patented by Ellen Fitz, a governess from New Brunswick. Fitz was the first woman involved in the design and manufacturing of globes, and her unique contribution to this educational tool – the globe’s mounting – was intended to help students understand the effects of the Earth’s daily rotation on its axis and yearly revolution around the sun. A Fitz globe is visible in the photograph of Miss Howe’s class.

2. Schools

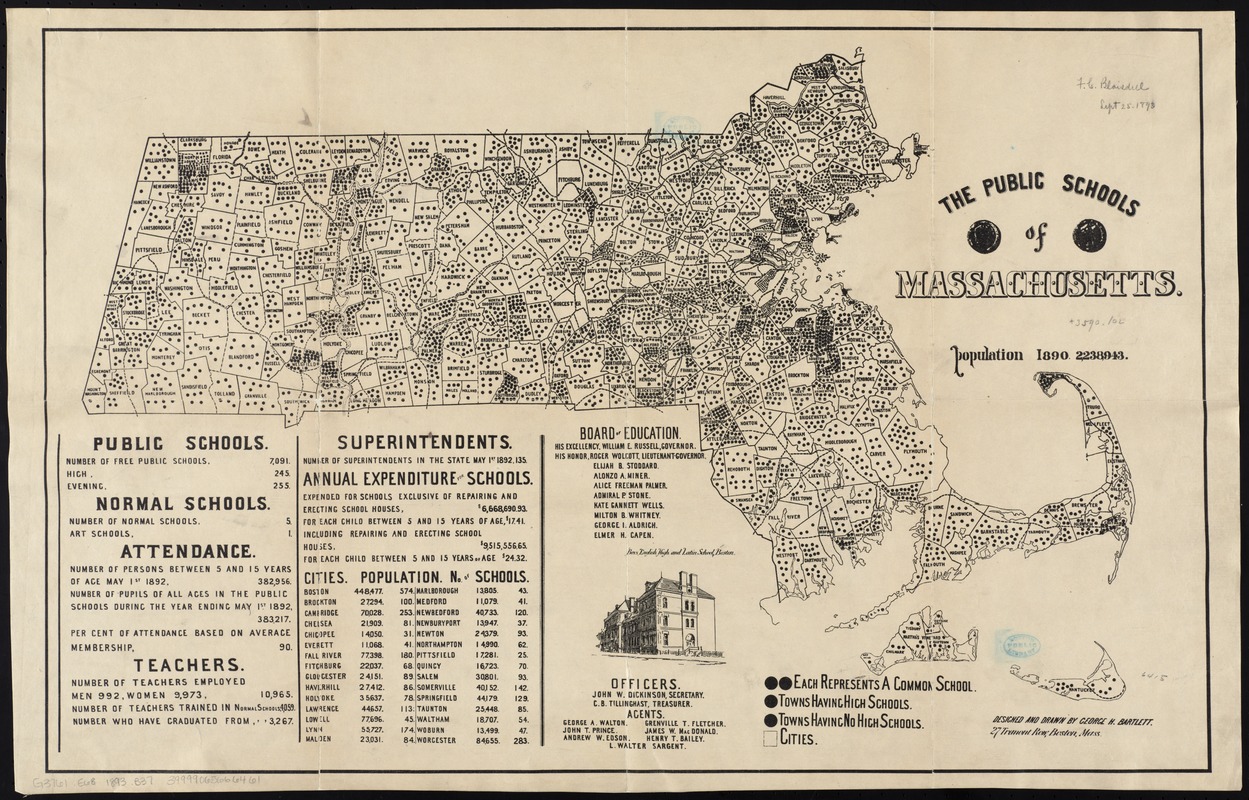

George Hartnell Bartlett

The Public Schools of Massachusetts

Boston, 1893.

Massachusetts has historically been a leader in providing free education for children since the late 18th century. After the American Revolutionary War, public education at the elementary level was open to both male and female children, and geography was consistently part of the curriculum. George Bartlett, an artist and school principal, produced this map illustrating the number of public schools by town throughout the state in 1892. At this time, there were over 7,000 public schools throughout the Commonwealth, with women accounting for over 90% of teachers.

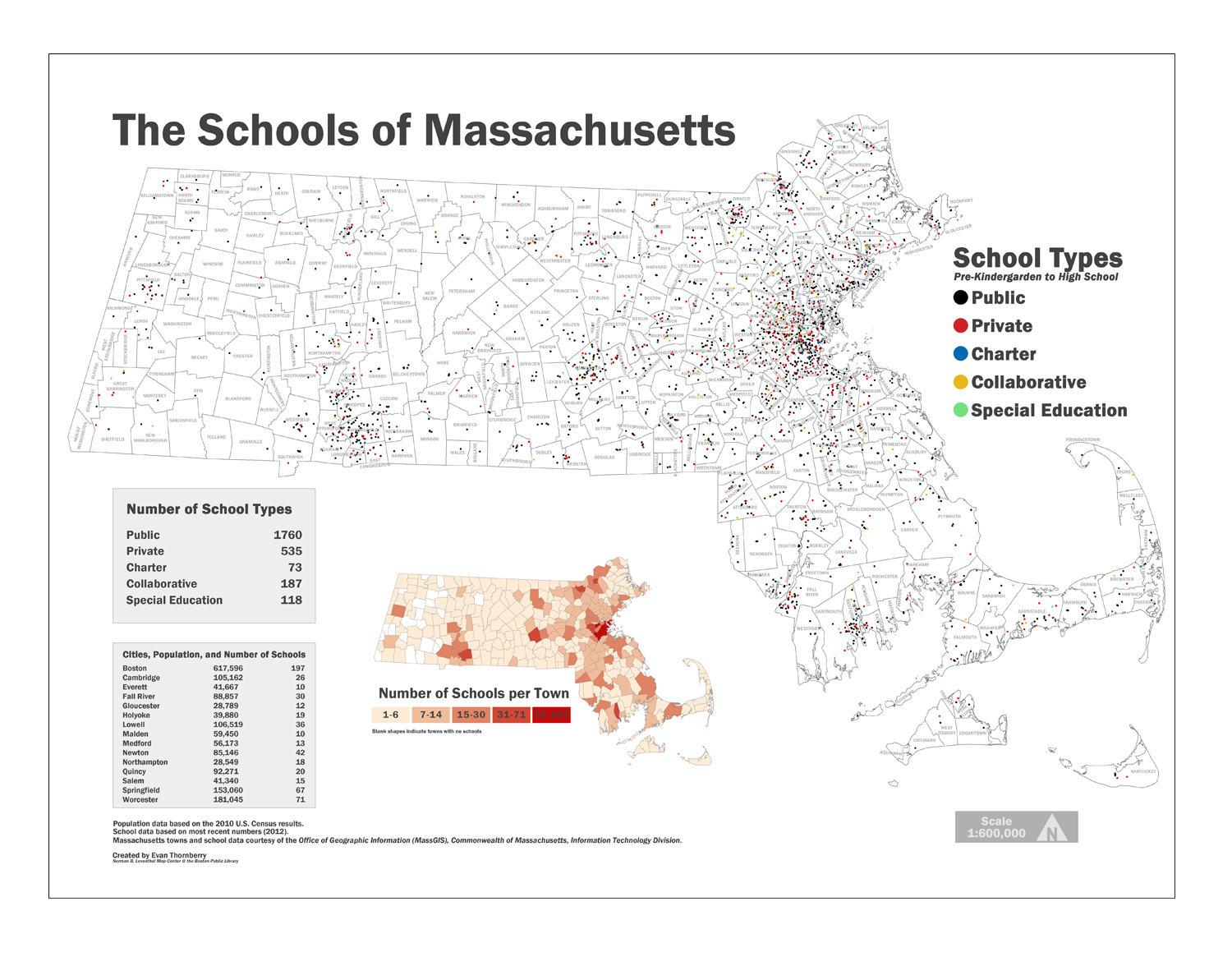

Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DOE) and MassGIS

Schools (PK-High School)

Boston, 2012. Map created by Evan Thornberry, 2014.

Courtesy MassGIS.

This modern map of Massachusetts illustrates the location of schools throughout the state for children from the pre-kindergarten through high school level. In contrast to the 19th century map, this contemporary map records not only public schools, but includes private, charter, collaborative programs and approved special education facilities as well. Based on data from February 2012, the modern map indicates that there were 1,860 public schools in operation in the state, as opposed to over 7,000 public schools in the late 19th century.

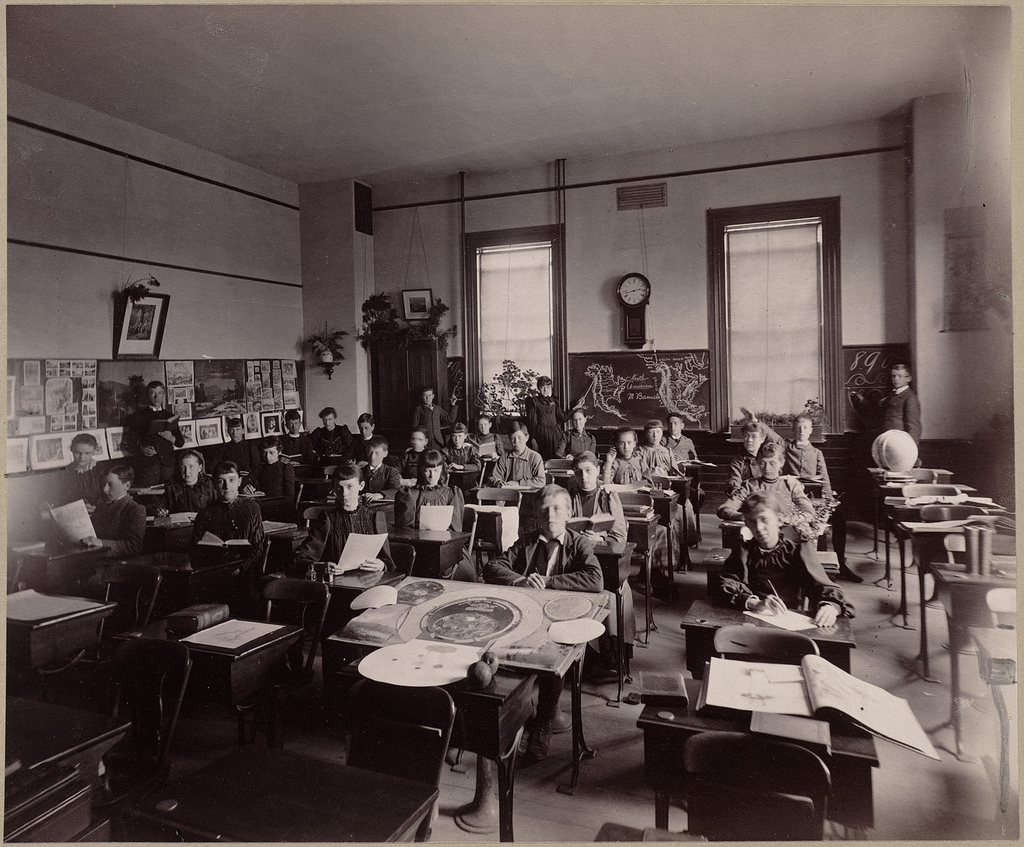

Augustine H. Folsom

Harris School, Class II. (Miss Howes)

Boston, 1892.

Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Print Department.

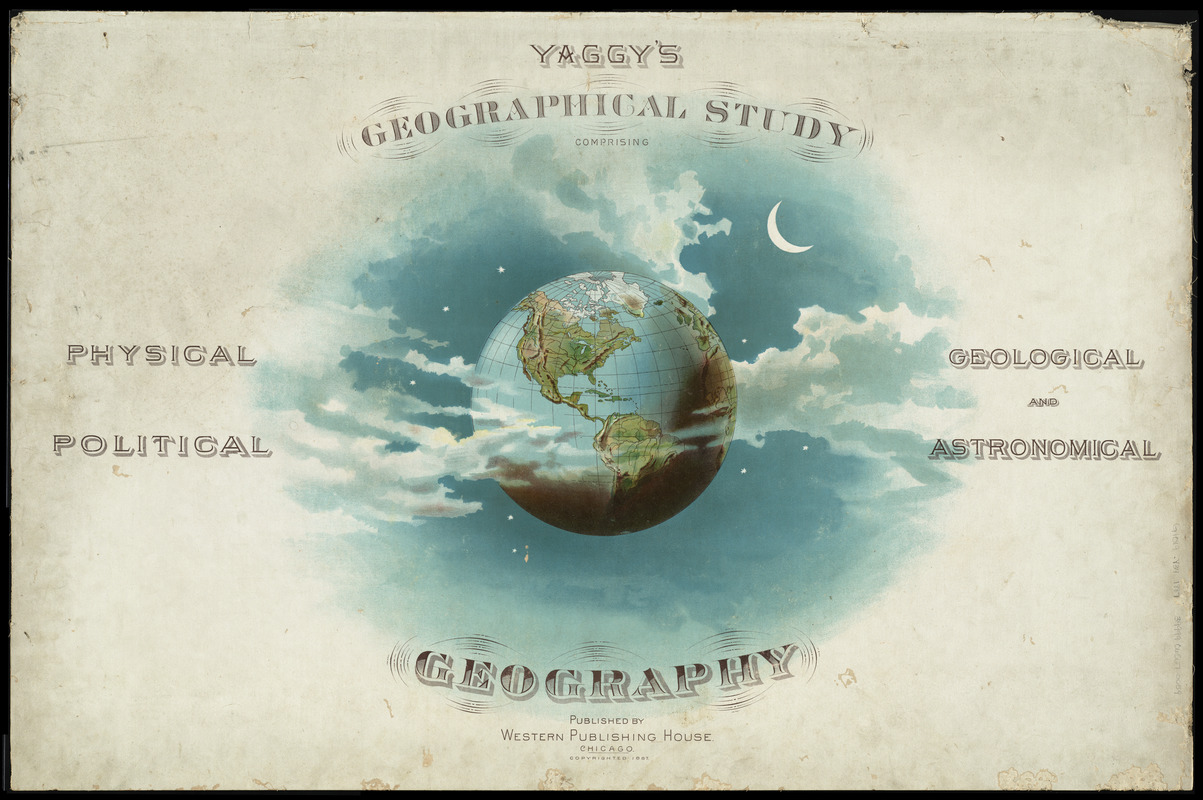

Photographer A. H. Folsom produced a series showing Boston public school classrooms as part of a survey commissioned by the school department in 1892-93. This photograph depicts Miss Howes’ class in the midst of a geography lesson, which is apparent from the copy of Levi Yaggy’s Geographical Study open on the front desk, a Fitz globe on a desk in the back of the classroom, and a teacher pointing to a map of North America on the blackboard. The Harris School was located at the corner of Adams and Mill Streets in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood.

Levi W. Yaggy

“Title page,” from Yaggy’s Geographical Study: Comprising Physical, Political, Geological and Astronomical Geography

Chicago, c1887.

One of many educational products produced by writer Levi Yaggy in the late 19th century, the Geographical Study was a collection of maps, charts and diagrams bound into an oversize carrying case. The maps and charts focus on subjects such as planetary systems, climate, population, economics, relief maps and physical geography. Yaggy intended for this collection to be used in classrooms by students, and issued a teacher’s handbook to assist with instruction. As seen in Folsom’s photograph, the Study was indeed used for geography lessons – right here in the city of Boston.

3. Female Education

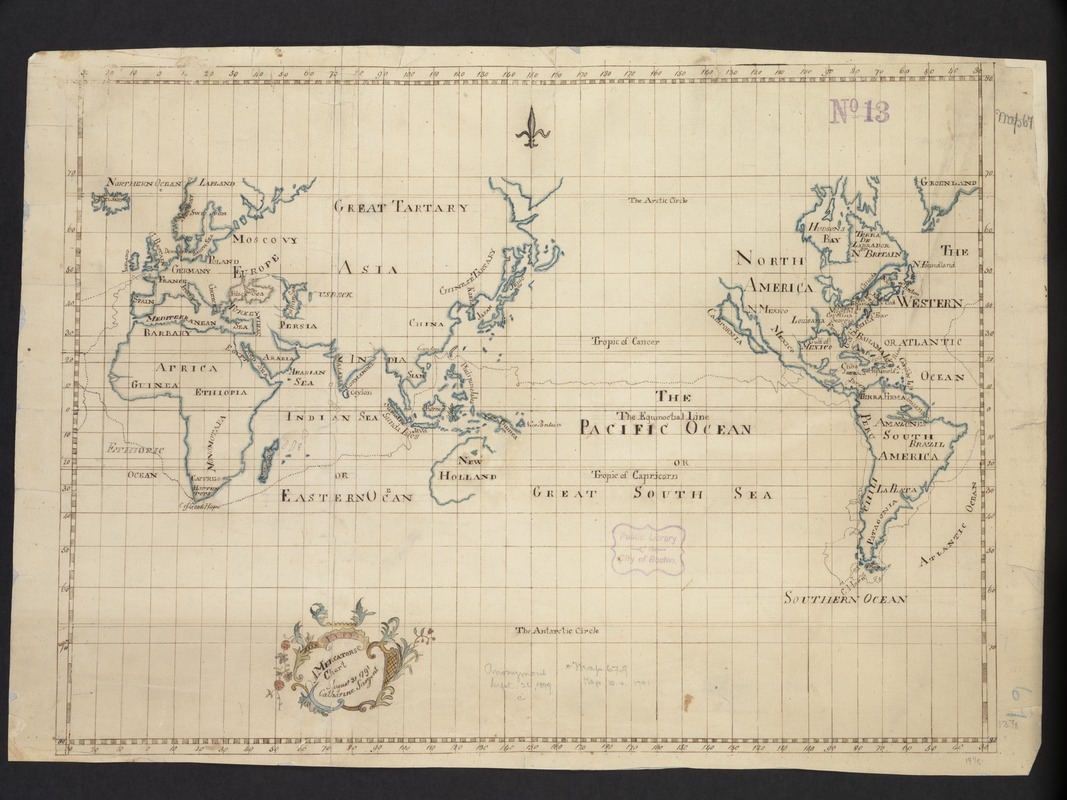

Catharine Sargent

A Mercator’s Chart

1791.

Catharine Sargent, a Boston schoolgirl in the late 18th century, created this manuscript map of the world most likely as a school geography project. During the late 18th and early 19th century, it was common practice for British and American female students attending private academies to prepare maps of various parts of the world by copying maps from books or atlases. Ms. Sargent’s map exercise is almost an exact copy of “A Chart Shewing the Track of the Centurion Round the World,” which accompanied George Anson’s account of his voyage around the world, first published in 1748.

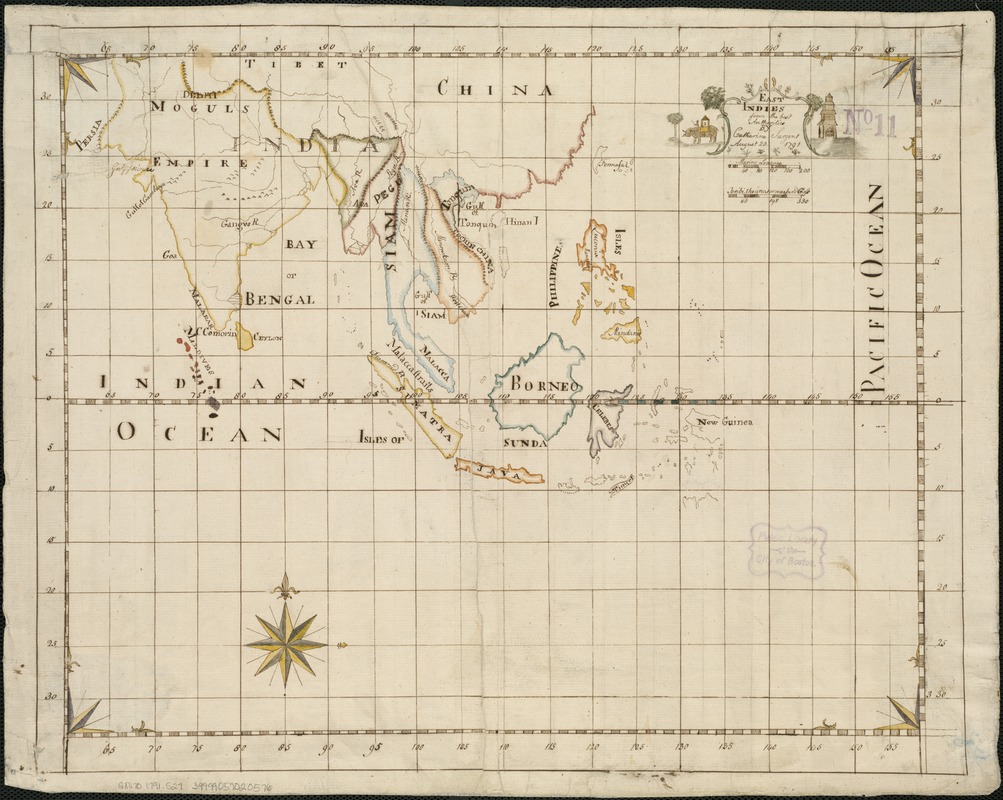

Catharine Sargent

East Indies from the Best Authorities

August 20, 1791.

Another example of Catharine Sargent’s manuscript school maps is her map of Asia, complete with a decorative title cartouche. Prior to the American Revolutionary War, females received little formal education. However, this changed in the new Republic. Dame schools, run by women in their homes, taught reading, writing and numbers to young children, and needlework to girls. Private female academies, founded in the late 18th century, greatly expanded upon the subjects previously taught to girls. The academies taught not only the basic subjects, but geography, history, and natural science as well.

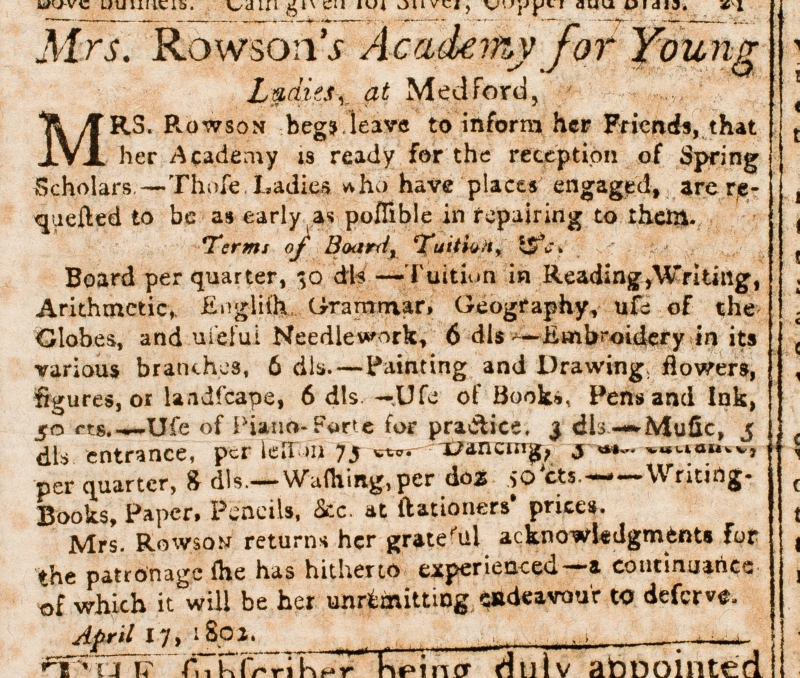

“Mrs. Rowson’s Academy for Young Ladies, at Medford,” from the Columbian Centinel. Boston, April 21, 1802.

Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

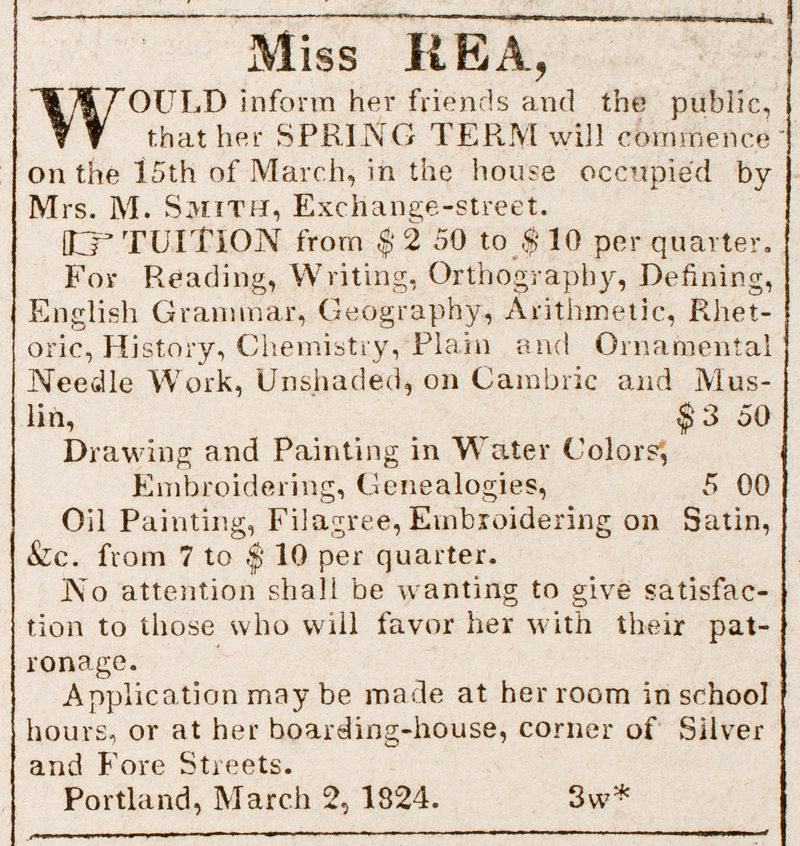

“Miss Rea …” from the Eastern Argus. Portland, Me., March 2, 1824.

Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

Private academies were a popular choice for middle-class and wealthy New England families who wished to formally educate their daughters. These 19th century advertisements from newspapers in Boston, Massachusetts and Portland, Maine, promote openings at two such schools. Susanna Rowson ran a successful academy in Medford, Massachusetts, and taught her students geography, the “use of globes,” and “useful needlework.” Miss Rea, based in Maine, similarly instructed young ladies in geography, needlework, and for an extra fee, embroidering on satin. Girls attending such academies could expect to receive instruction in academic subjects, as well as home economics.

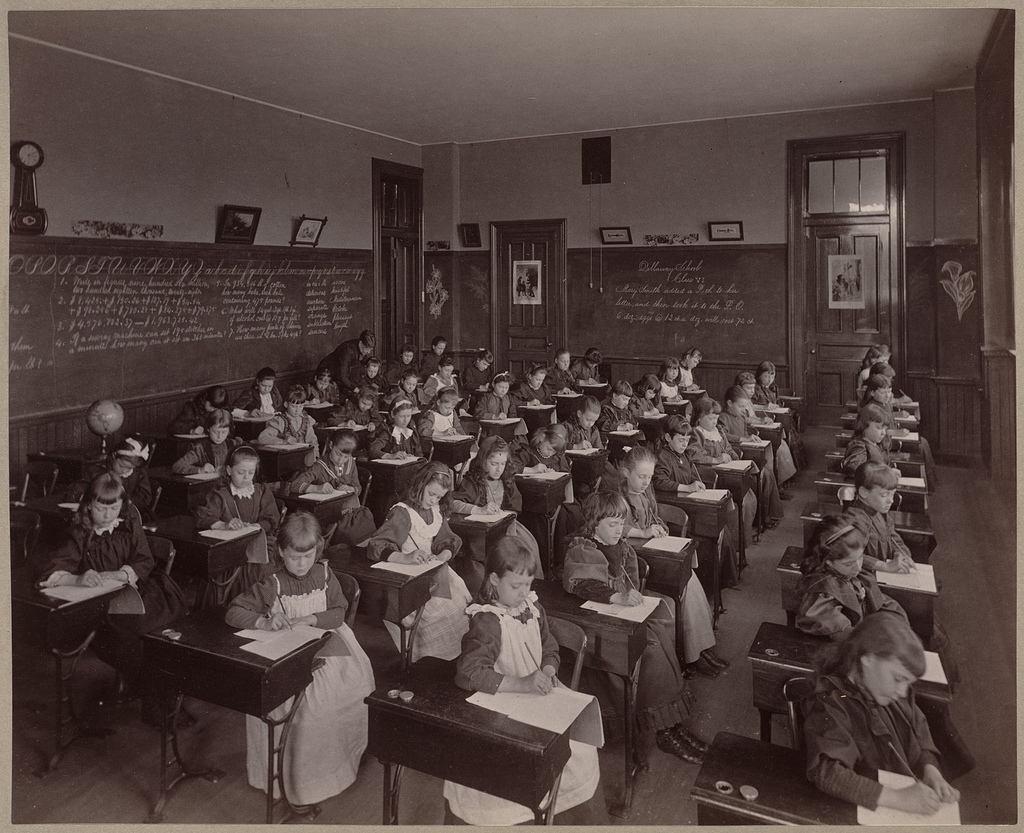

Augustine H. Folsom

Grammar School, class VI. Dillaway District

Boston, 1892.

Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Print Department.

In the early 19th century, tax-supported public institutions began to offer free education to both males and females in Massachusetts. By 1852, school attendance for children between the ages of 8 and 14 for at least 12 weeks of the year, was mandatory in the Commonwealth. A Joslin terrestrial globe sits on a desk at the far left in this grammar school class of a girls’ school in Roxbury. These globes were purchased by the City for every Boston classroom above the primary level at the time.

[Terrestrial Globe]

Westtown, Penn., [ca. 1810-1843]

Embroidered globes, such as the one displayed here, were unique to the Westtown School – a Quaker boarding school in West Chester, Pennsylvania. Made only at this school by the female students between 1804 and 1844, these items were intended to teach mathematical geography, astronomy, the use of globes and needlework simultaneously. Young girls learned sewing skills by first making samplers, while older girls produced items such as pocket books, pin cushions, and globes. As Quakers, Westtown girls produced simple objects rather than ornate needlework pictures such as the embroidered satin map.

How the globes were made: Each Westtown globe is between 5 to 6 inches in diameter, and are made of silk over a stitched canvas form, which is stuffed with raw wool. The form was made first, and then the silk gores were stitched together. A seam was left open in the silk to insert the form. The outlines and graticule (latitude and longitude lines) were made with simple stitches, as were parallels and meridians. The lettering was then inked onto the silk. Only a few of the 30 known globes show the maker’s name. The globes were designed to be used, and many were mounted on wooden stands – the globe displayed here is an example of that variety. Westtown teacher Samuel Gummere’s Definitions and Elementary Observations in Astronomy was used as a reference when constructing the globes.

4. Games

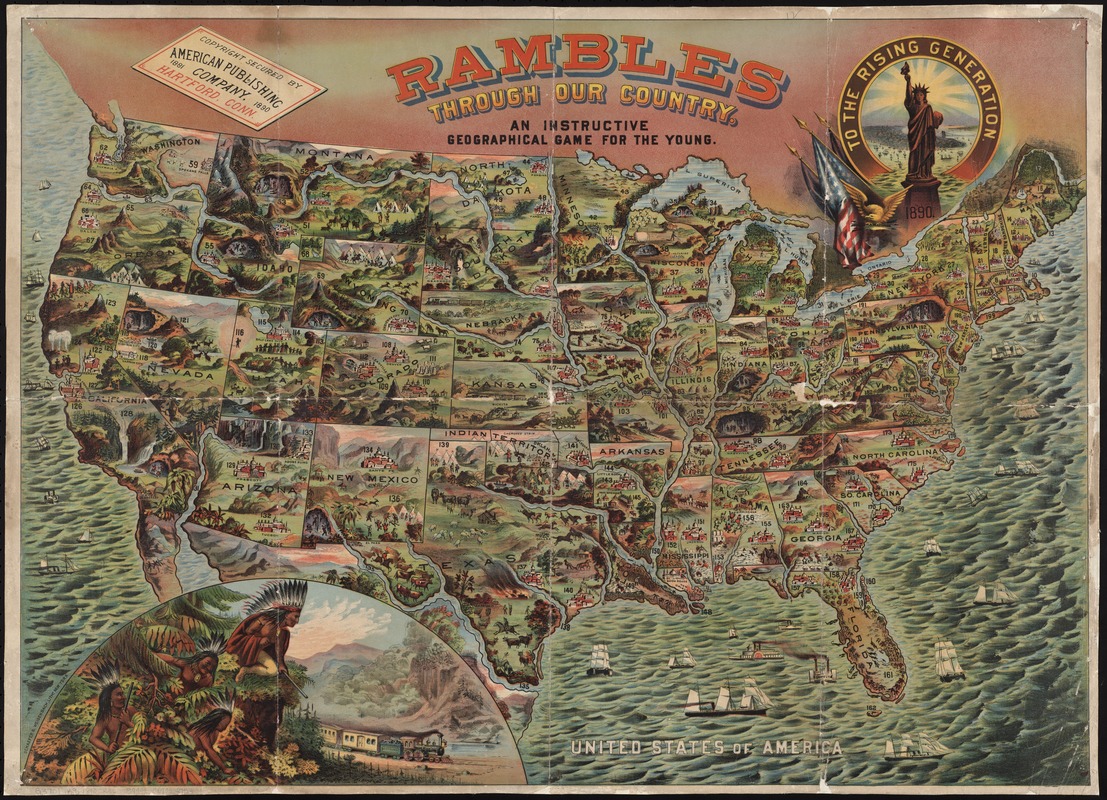

American Publishing Company

Rambles Through Our Country: An Instructional Geographical Game for the Young

Hartford, Conn., c1890.

Educational games were a popular way of teaching geography, map reading and history to children in the 19th century. Displayed here is an example from 1890, in which players had to complete a “grand tour” across a colorful and detailed map of the United States. Play began in Hartford, Connecticut, where the game was published, and finished in New York City. There are 200 stops on the tour. Each player spun a numbered wheel in order to advance. At each stop, the player read aloud a description of that location from a corresponding booklet.

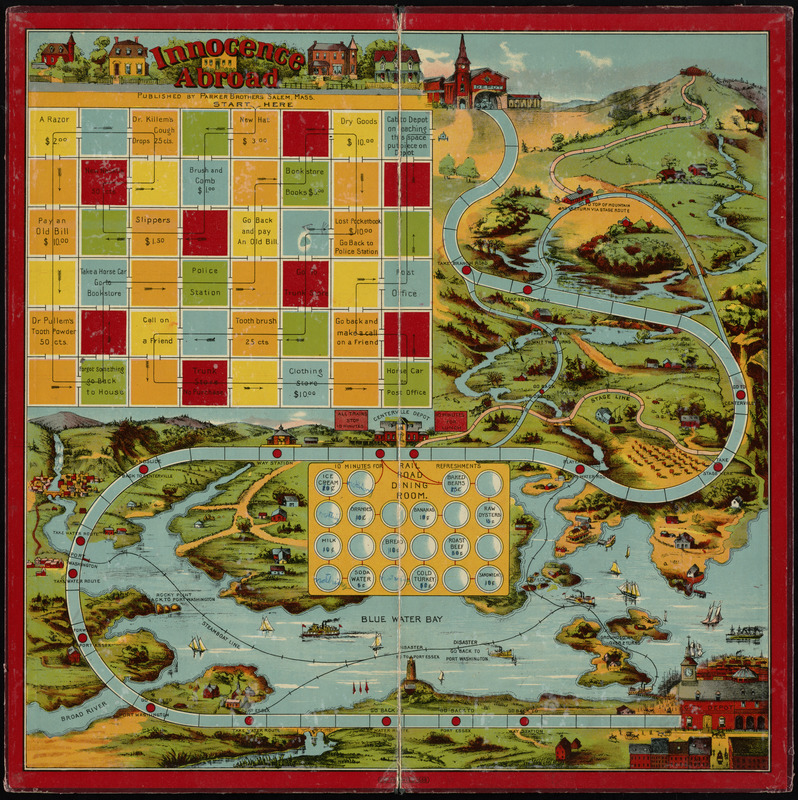

Parker Brothers

The Good Old Game of Innocence Abroad

Salem, Mass., 1888.

The colorful and engaging board game displayed here was based on a popular book by the best-selling author Mark Twain, entitled The Innocents Abroad. As did the characters in Twain’s book, players ventured across the land for a memorable journey, experiencing costs and perhaps troubles as they would in real life. Appealing to many Americans’ desire to travel and experience new places, the game was quite popular, and the company sold many thousands of copies.

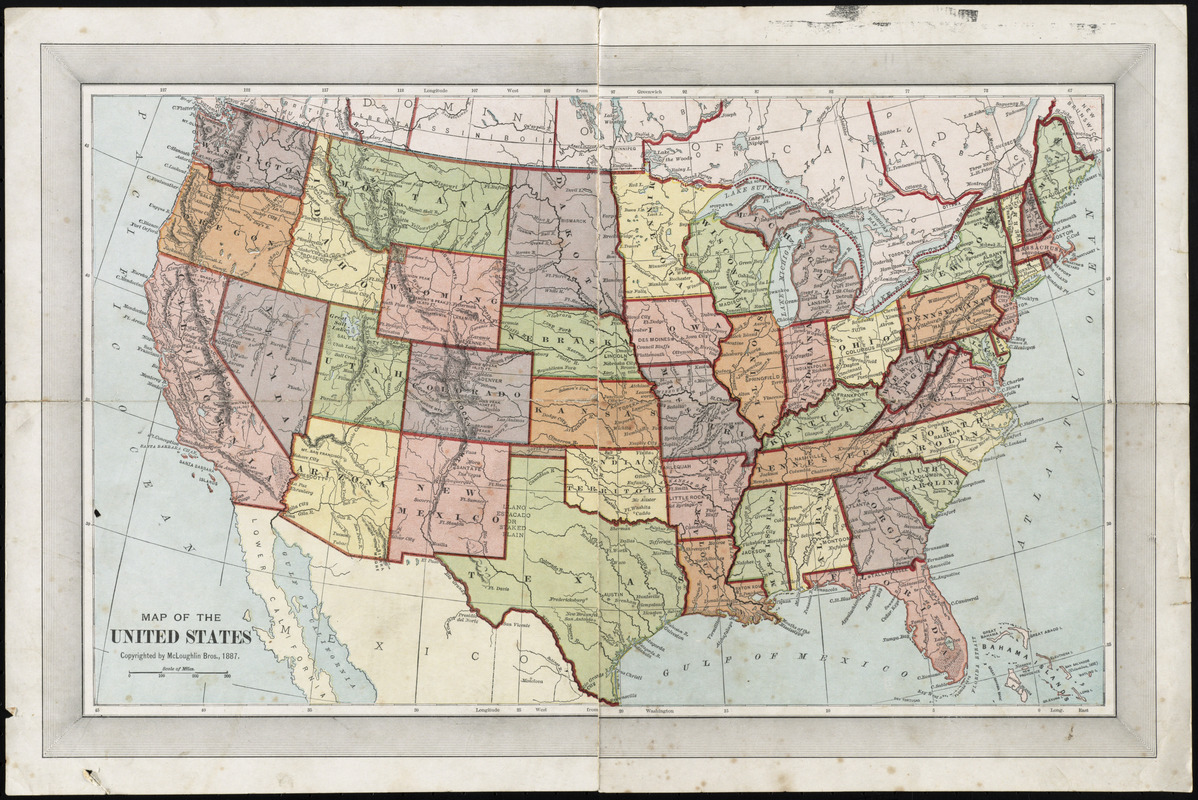

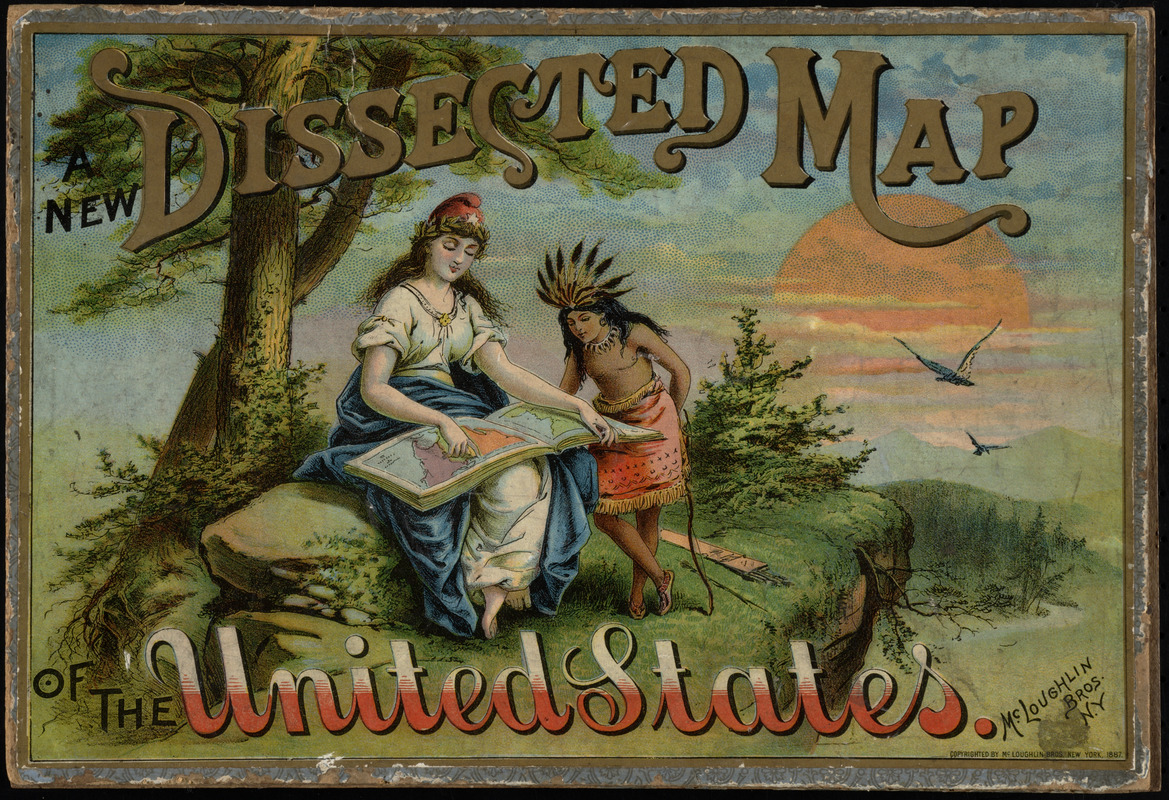

Produced by the most successful game maker of the time, this jigsaw puzzle was another method of making geography fun and interesting. Designed as learning tools, the earliest puzzles, known as “dissected maps,” did not contain randomly cut pieces, but rather followed country or state borders. Jigsaw puzzles with random pieces eventually replaced this practice. In this puzzle dating from 1887, a child would become familiar with United States geography. The puzzle is housed in a decorative box depicting symbols of America, including a seated Columbia holding an atlas, and a Native American in indigenous dress.

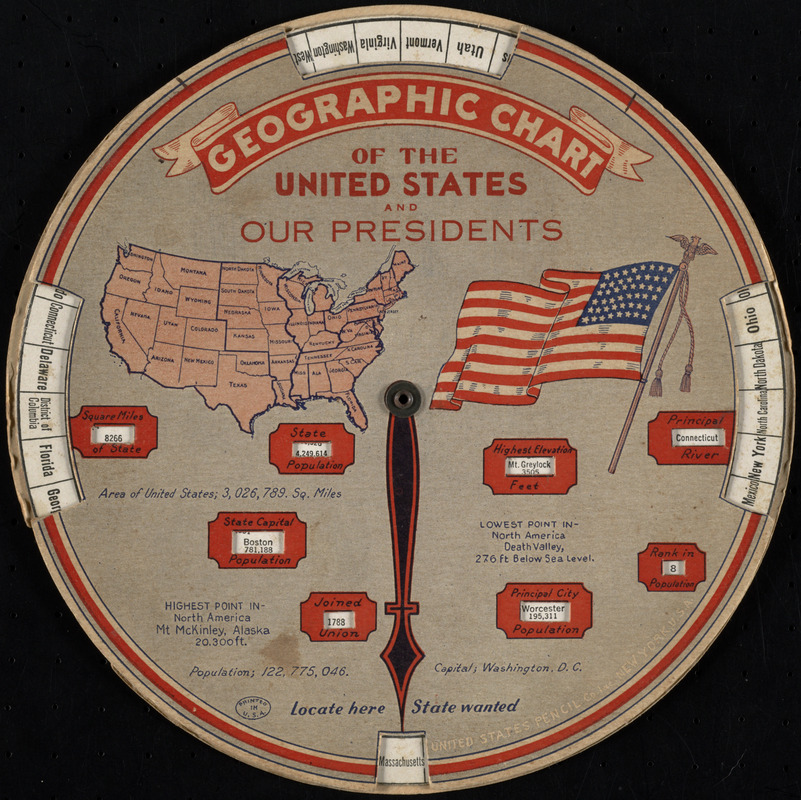

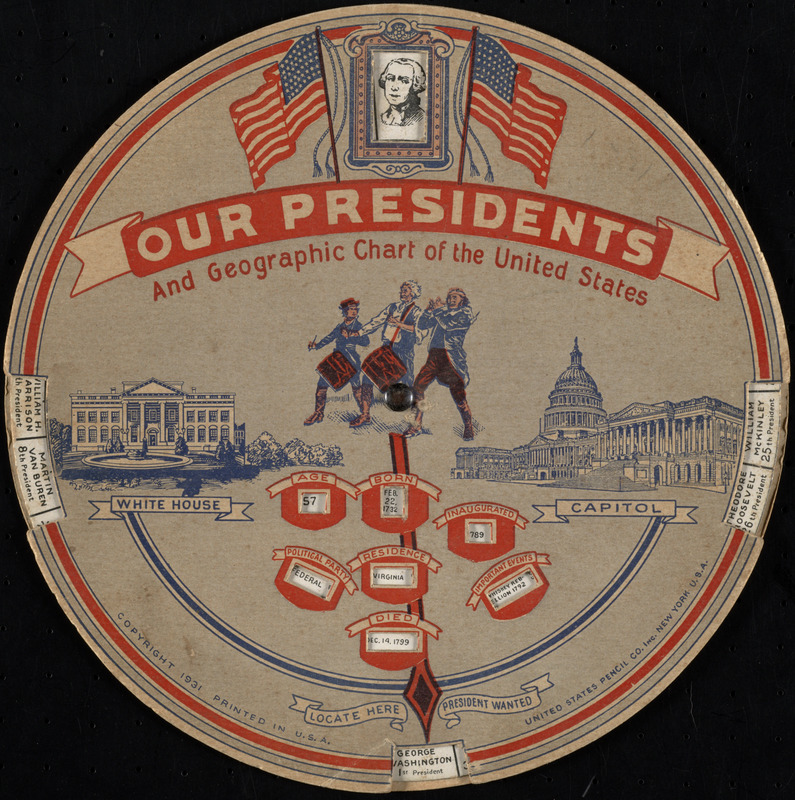

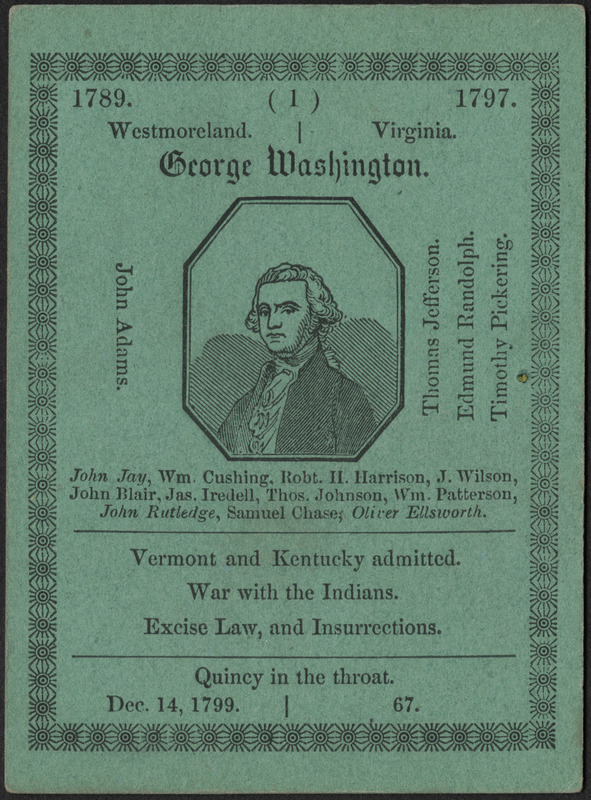

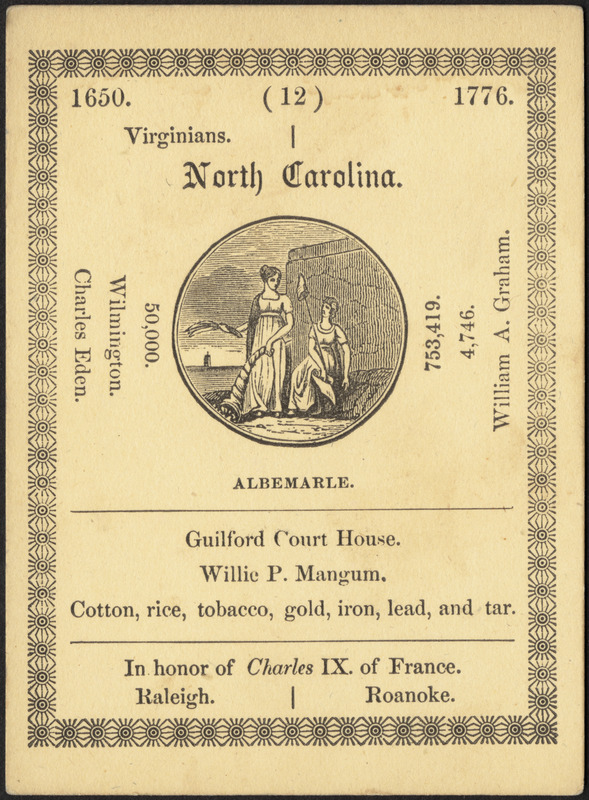

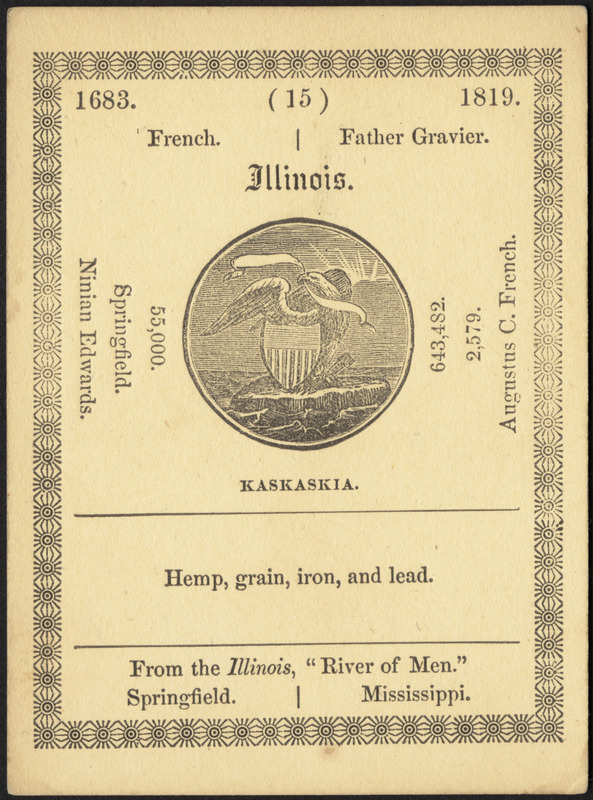

United States Pencil Company

Our Presidents and Geographic Chart of the United States

New York, c1931

William Chauncy Langdon

The Game of American Story and Glory

New Orleans, La., 1846.

These two objects focus on geography and the history of the Presidency of the United States. William Langdon’s mid-19th-century card game contains 40 cards – 1 explanatory card, 11 featuring Presidents, and 28 describing the states of the Union. The object of the game was to collect all cards by correctly stating facts related to the cards that were not in the player’s hand. An early 20th century chart similarly presents facts related to the Presidents and each state.

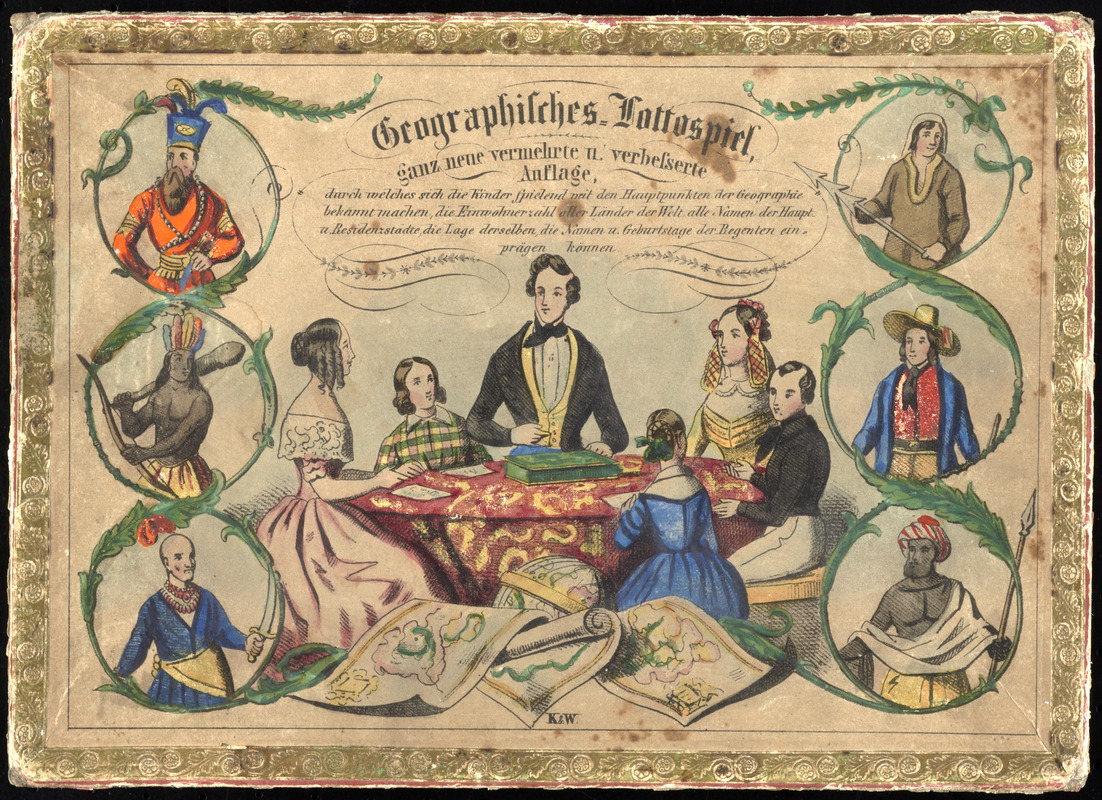

E. Serre

Loto des 5 Parties du Monde: Races Humaines Productions Végétales et Animales

Paris, ca. 1905.

Games designed to teach geography were prevalent in Europe as well. Displayed here are two “lotto” games, which are similar to modern-day Bingo games. A 19th-century German version depicts a family playing the game on the cover, surrounded by peoples of the world, and an early 20th-century French game illustrates people, vegetation and natural landscapes from around the world. The object of both games was to fill each board, representing geographic locations, by collecting tiles or cards corresponding to those locales. These games not only imparted geographical knowledge, but also taught social, cultural, and natural science.

5. Atlases

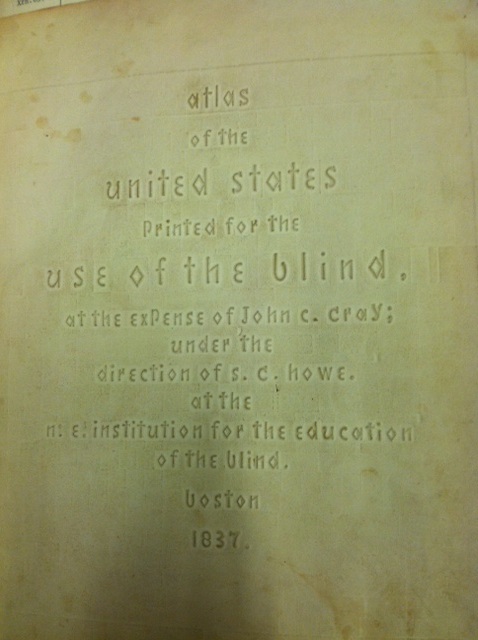

Samuel Gridley Howe

Atlas of the United States, Printed for the Use of the Blind

Boston, 1837.

Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Rare Books and Manuscripts Department.

Atlases were an essential part of a 19th-century classroom. Samuel Gridley Howe, first director of the Perkins School for the Blind, created this atlas to teach his students the geography of the United States. The pages of Howe’s atlas are composed of raised stylized letters, rather than Braille code, invented only 16 years earlier in France. Students could feel the outlines, shapes and boundaries of 23 states. Features such as rivers, towns, and population statistics were also included on each map. Howe’s development of embossed maps revolutionized the way blind students learned geography in the 19th century.

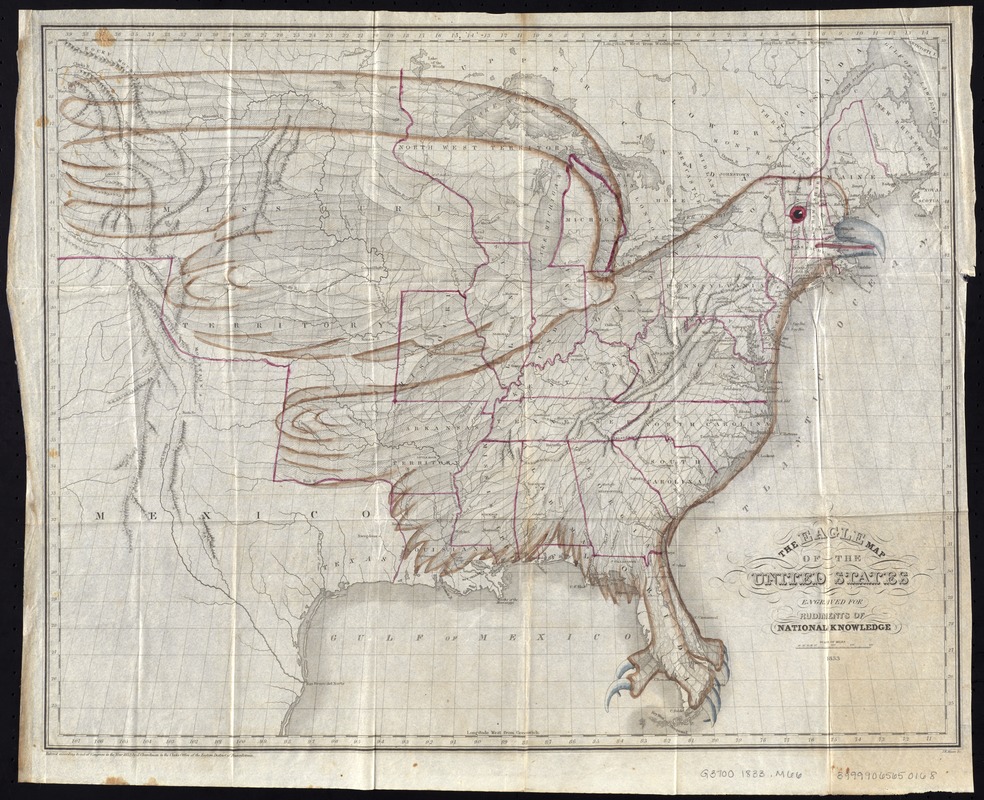

Joseph Churchman and Isaac W. Moore

The Eagle Map of the United States

Philadelphia, 1833.

From Rudiments of National Knowledge … a geography book published in 1833, this unique map shows the states in outline color with an eagle sitting on top of the nation. Intended to teach geography, children could memorize the location of the states by referring to parts of the bird, such as the talons which represent Florida. Indigenous to North America, the bald eagle became the national bird of the United States in 1782, symbolizing strength, courage and freedom. Relating the Nation’s geography to a representation of national identity solidified the importance of geographic education at the time.

Nathaniel Gilbert Huntington

The Common School Atlas, Drawn and Engraved on Steel, to Illustrate and Accompany the Introduction to Modern Geography

Hartford, Conn., [1836].

These two school atlases from the early decades of the 19th century provided visual aids in the form of maps to supplement geography textbooks. At this time, geography textbooks were constructed as catechisms – long passages of text from which the student was to read from then answer questions. These paragraphs on countries listed places and natural features such as mountains and rivers. This type of rote memorization was common in teaching methods of the time. The school atlases displayed here contain maps which would help students answer questions, and illustrations which depict historical events to supplement their geographical learning.

William Harvey

“Germany,” from Geographical Fun: Being Humorous Outlines of Various Countries

London, [1869].

The unique atlas referenced here contains twelve maps of European countries, each being portrayed as a stereotypical caricature of the location. Similarly to the creators of the Eagle Map, the atlas’ author, William Harvey, believed that visualizing geography in such a way would make the subject easier to understand, and more educational. Thus, he drew the major European countries as human figures reflecting national stereotypes, such as England in the form of Queen Victoria, and Scotland as a bagpipe player dressed in a kilt. Germany portrayed as a lady dancing is reproduced here.

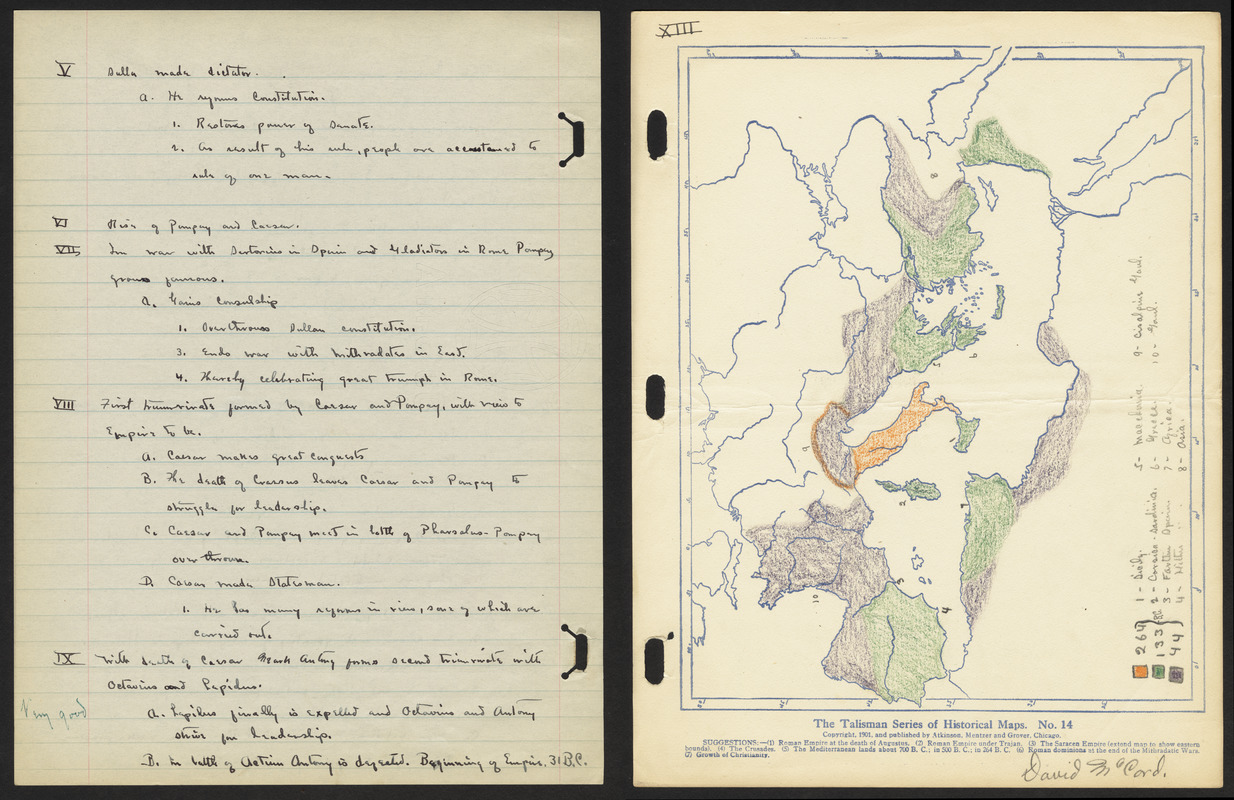

David W. McCord

History 2

1914.

Progressive 19th-century educators such as Emma Willard and William Channing Woodbridge emphasized the importance of teaching history and geography simultaneously. This practice, which continued into the early 20th century, is evident in the notebook of Lincoln High School student David McCord, displayed here. David’s book from his history class in 1914 contains notes with corresponding maps, such as those related to the Roman Empire. Historical maps allowed students to visualize places in the past, as David’s map of the Holy Roman Empire does.

6. Globes

A variety of globes were available for personal, educational, and institutional use in the 19th century. Displayed here are reproduced pages of a sales catalog from New York distributor Baker, Pratt & Co., who specialized in school merchandise. The company offered every size model, from handheld pocket globes to desk-size globes and large globes on elaborately carved stands. As illustrated by photographs in this exhibition, Boston classrooms featured desk-top globes, as well as pedestal style models.

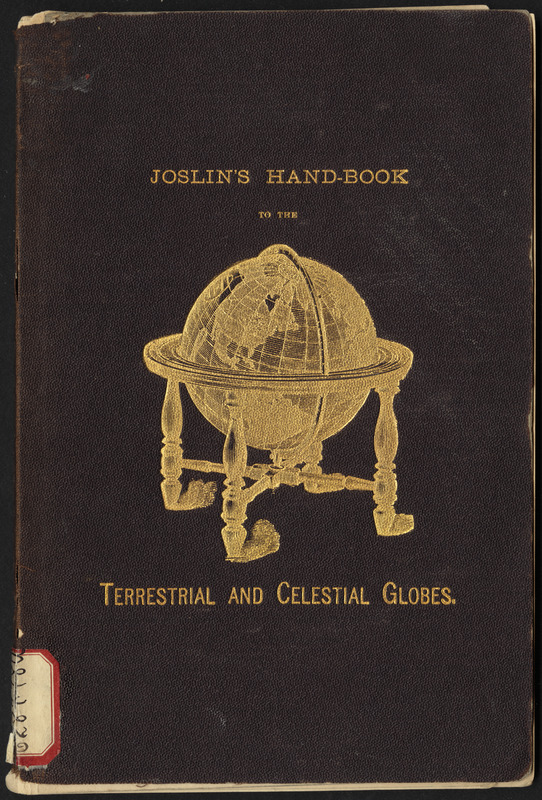

Gilman Joslin.

“[Cover]” and “[Page 5]” from Joslin’s Terrestrial and Celestial Globes.

Boston, 1885.

A number of instructional manuals on the use of globes were written in the 19th century. Manuals were written by educators to assist children using globes in the classroom, or by globe makers themselves, to explain the functions of their product. Globe maker Gilman Joslin published his instructional manual on the use of his terrestrial and celestial globes in the late 19th century. His concise work describes features of his globes, and why they are useful educational tools. Joslin’s desk globe was present in every elementary level Boston classroom in the late 19th century.

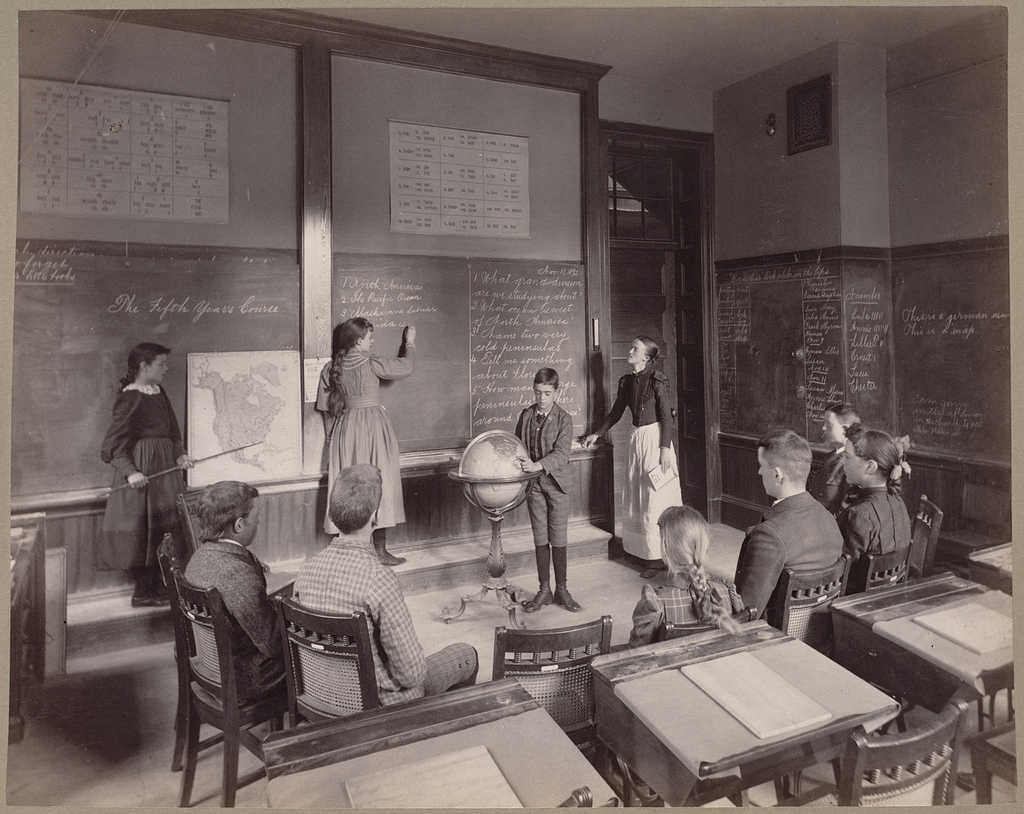

Augustine H. Folsom

Geography

Boston, 1892.

Reproduction Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Print Department.

A.H. Folsom captured this scene of a geography lesson at the Horace Mann School for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing in 1892. This school opened in Allston, Massachusetts in 1869, making it the oldest public day school for the Deaf in the nation. In this photograph, a girl points to the state of Florida on a map of North America, while a boy points to the location on a globe. A girl at the blackboard writes the state’s name for the class to see. Large pedestal globes such as the one seen here, were costly items, and would have been shared by the entire class.

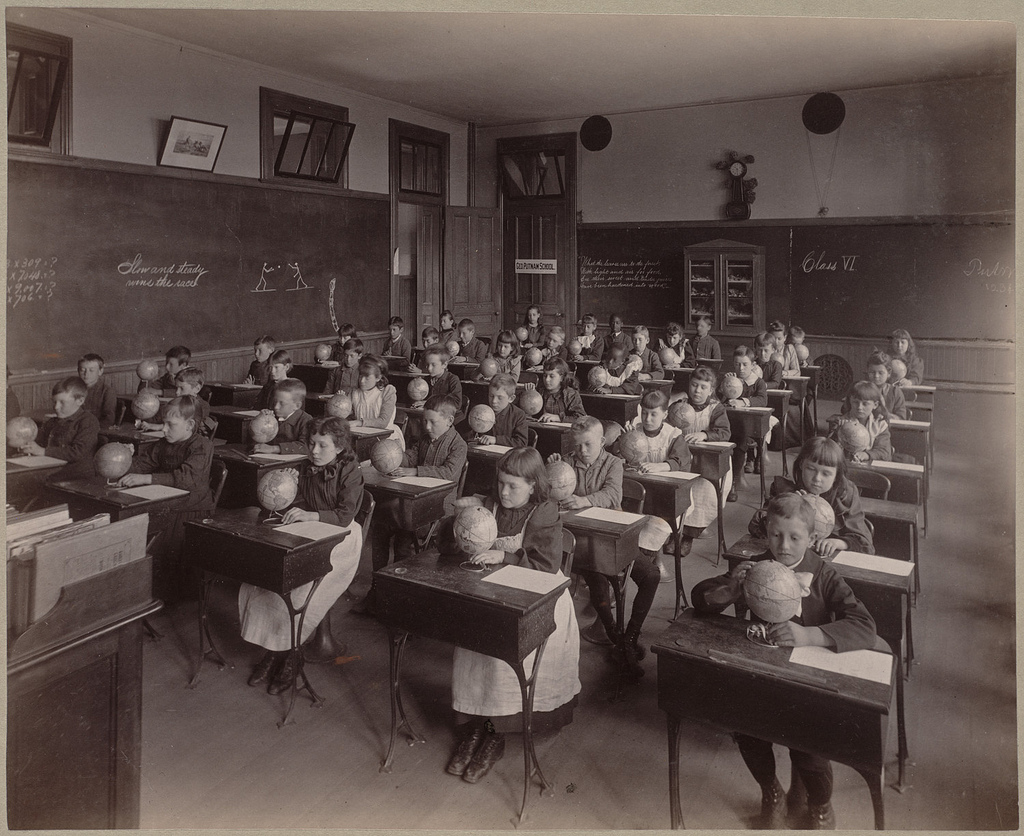

Augustine H. Folsom

Fourth Grade – George Putnam School

[Boston], 1892.

Reproduction Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Print Department.

A.H. Folsom also took this picture of a fourth-grade class with nearly every student examining a small desk globe in 1892. As in his other photographs in this exhibition, Folsom’s snapshot speaks to the importance of geography in the late-19th-century Boston Public School curriculum. This classroom was at the George Putnam Grammar School which was located at 2025 Columbus Avenue. Today, the site of the Putnam school is across the street from the Egleston Square Branch of the Boston Public Library.

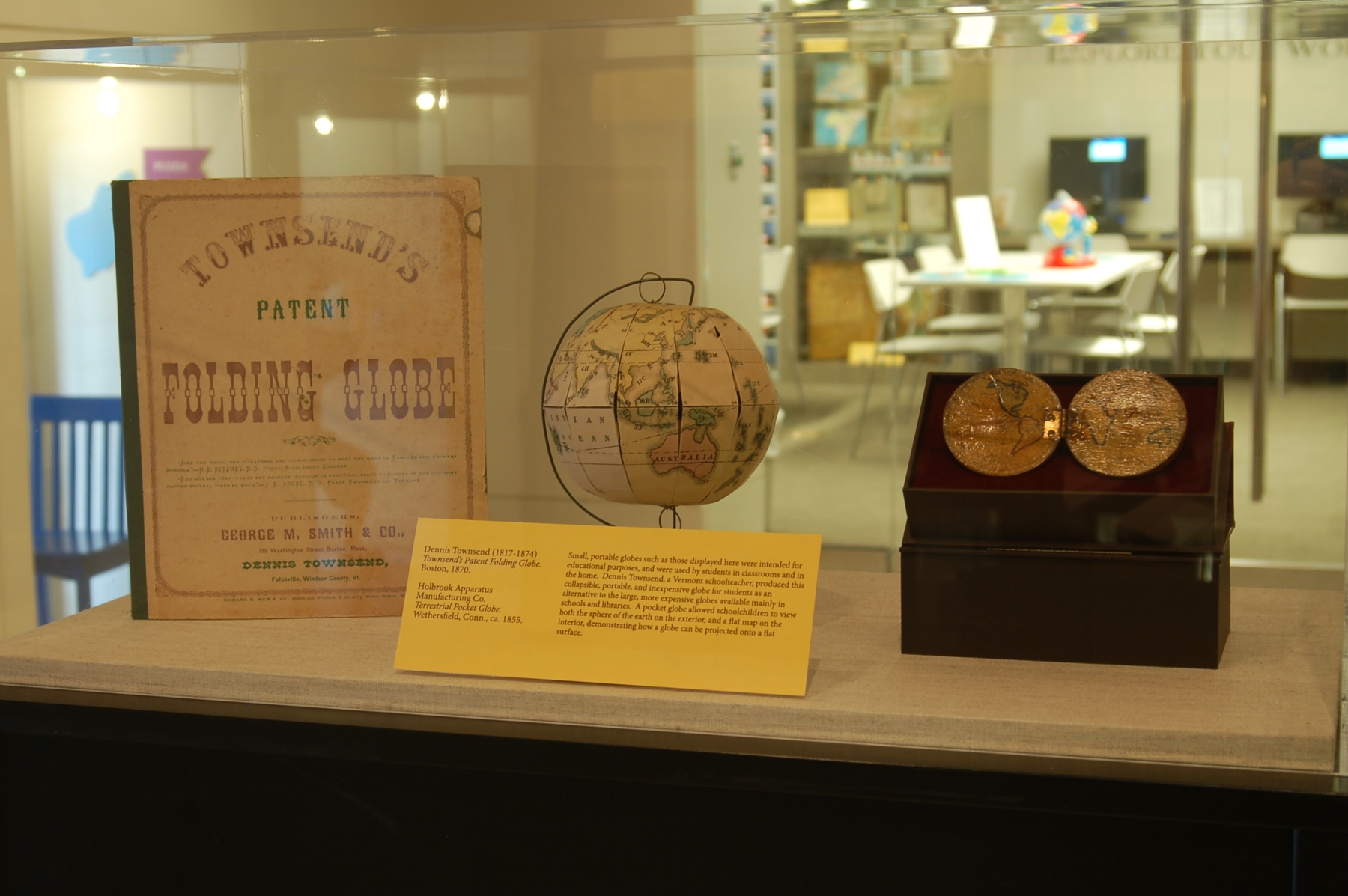

Small, portable globes such as those displayed here were intended for educational purposes, and were used by students in classrooms and in the home. Dennis Townsend, a Vermont schoolteacher, produced this collapsible, portable, and inexpensive globe for students as an alternative to the large, more expensive globes available mainly in schools and libraries. A pocket globe allowed schoolchildren to view both the sphere of the earth on the exterior, and a flat map on the interior, demonstrating how a globe can be projected onto a flat surface.

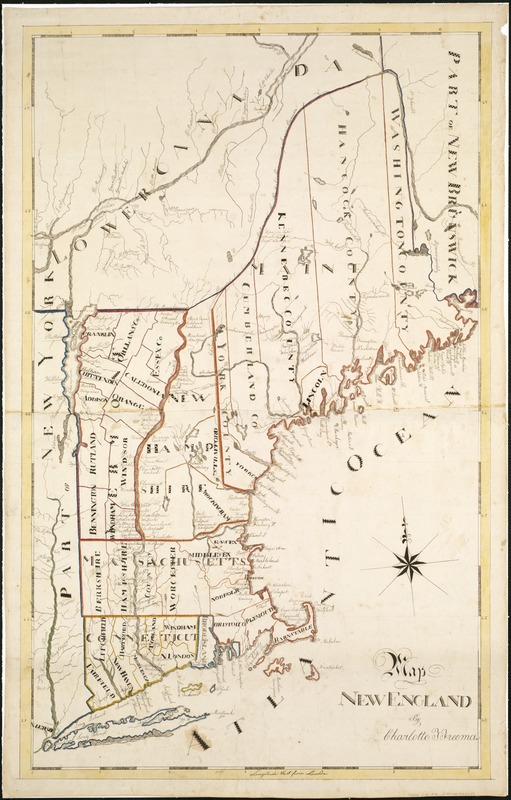

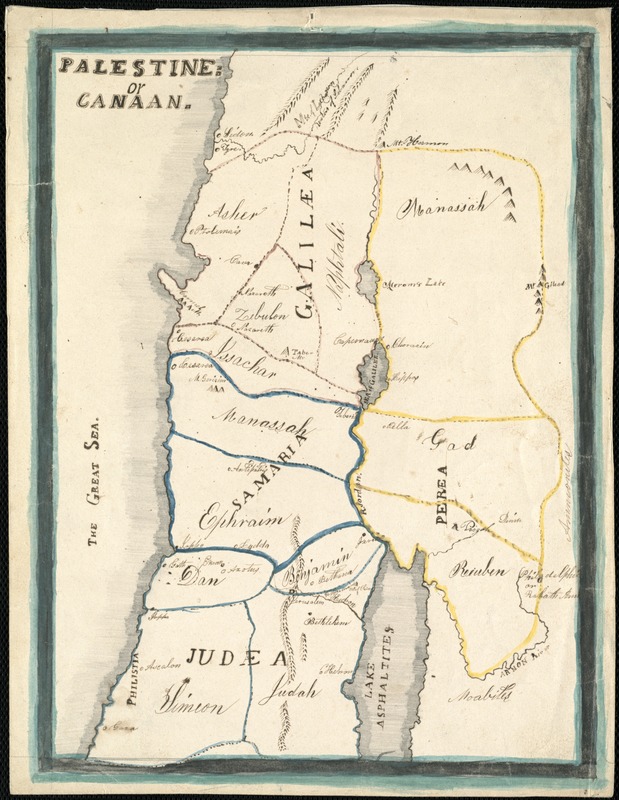

7. Geography Projects

Copying maps onto paper was a common assignment for both girls and boys attending academies in the 19th century, as students practiced geography and penmanship simultaneously. The maps displayed here represent geography projects of two 19th-century schoolgirls. Charlotte Freeman’s map of New England details towns, counties and natural features such as rivers and lakes from Maine to Connecticut. Phebe Nichols produced her map of Palestine while a student at the Windham Phonetic School – a Quaker boarding school in Windham, Maine. As was the practice at Quaker schools, this map was executed in a plain, utilitarian style.

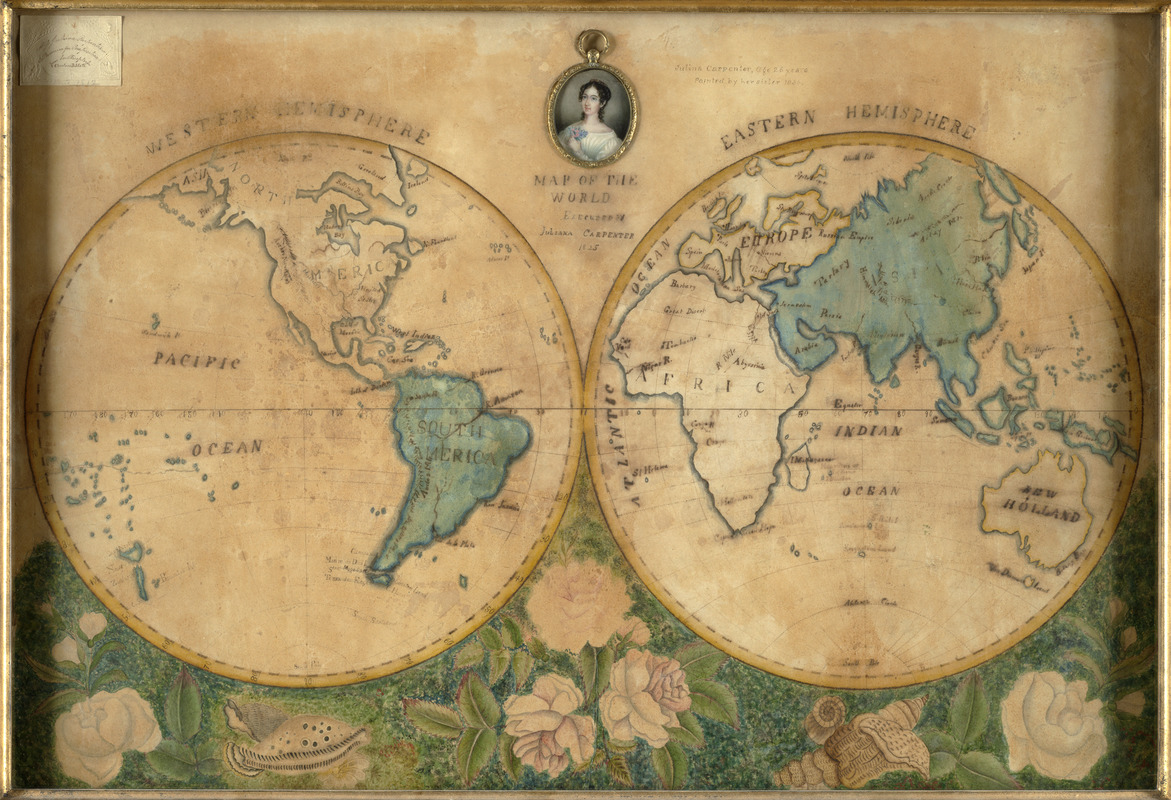

Juliana Carpenter

Map of the World

1825.

Private Collection.

Drawing maps of the world in two hemispheres was a popular geography project of 19th century schoolchildren. A young woman named Juliana Carpenter created this example when she was 15 years old. A reward for skill in map composition is in the upper left corner, and a miniature portrait of the artist at age 26, painted by her sister, is in the center. The addition of the large floral border suggests that this map was made at a private academy. This example stands in stark contrast to the simpler Quaker-made maps, which typically have fewer embellishments and simple garlands of vines and leaves.

The World With all the Modern Discoveries

England, [late 18th-early 19th century].

Private Collection.

Recent international conflicts and voyages by Captain Cook and others made the study of geography exciting at the time this map was made. Elaborate embroidered maps such as the English example displayed here, were executed by wealthy girls in formal academic settings using costly materials such as satin and silk. Such projects were designed to combine instruction in both geography and needlework, as sewing skills were essential for the production of clothing and monogramming linens at the time. The decorative map shown here depicts the world on a double hemisphere, and would have been proudly displayed on a wall.

Thankful Vincent

The World

1823.

Private Collection.

This double-hemisphere world map may be the work of a Quaker girl from Plainfield, Vermont, and is backed on an 1829 newspaper published near Montpelier. A young Thankful Vincent decorated her world map with simple garlands of vines and flowers around the title and her name. She also included embroidery along the margins of the map, at the top center, and in each corner. This schoolgirl map is a charming example of a young student’s combined geography, penmanship and needlework project.

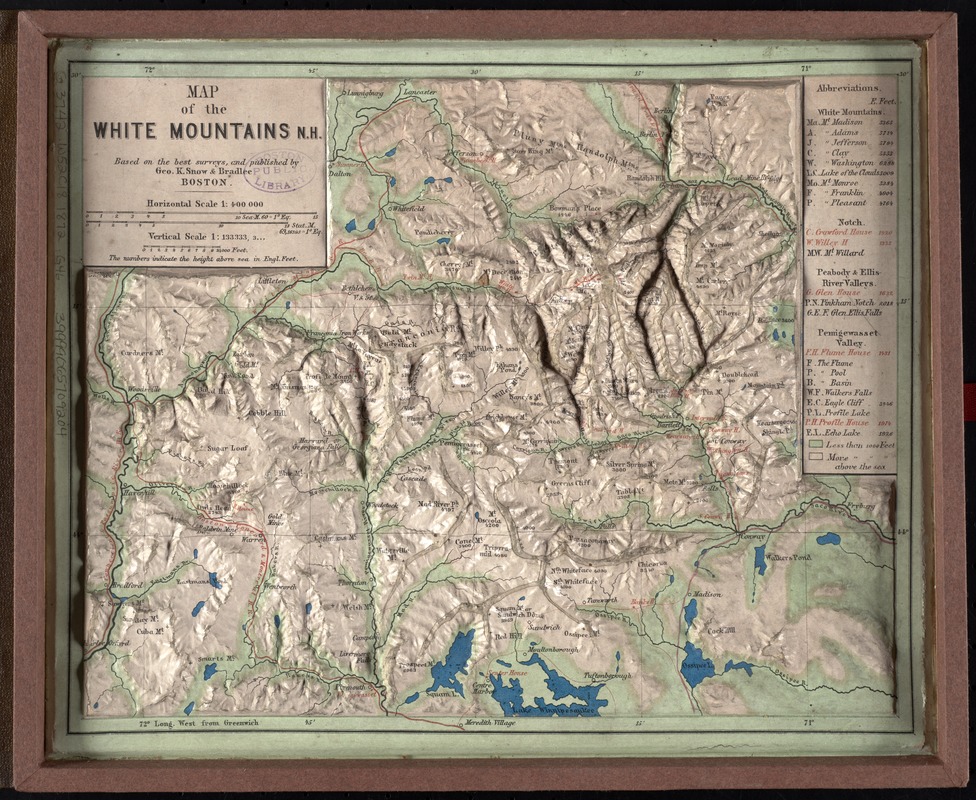

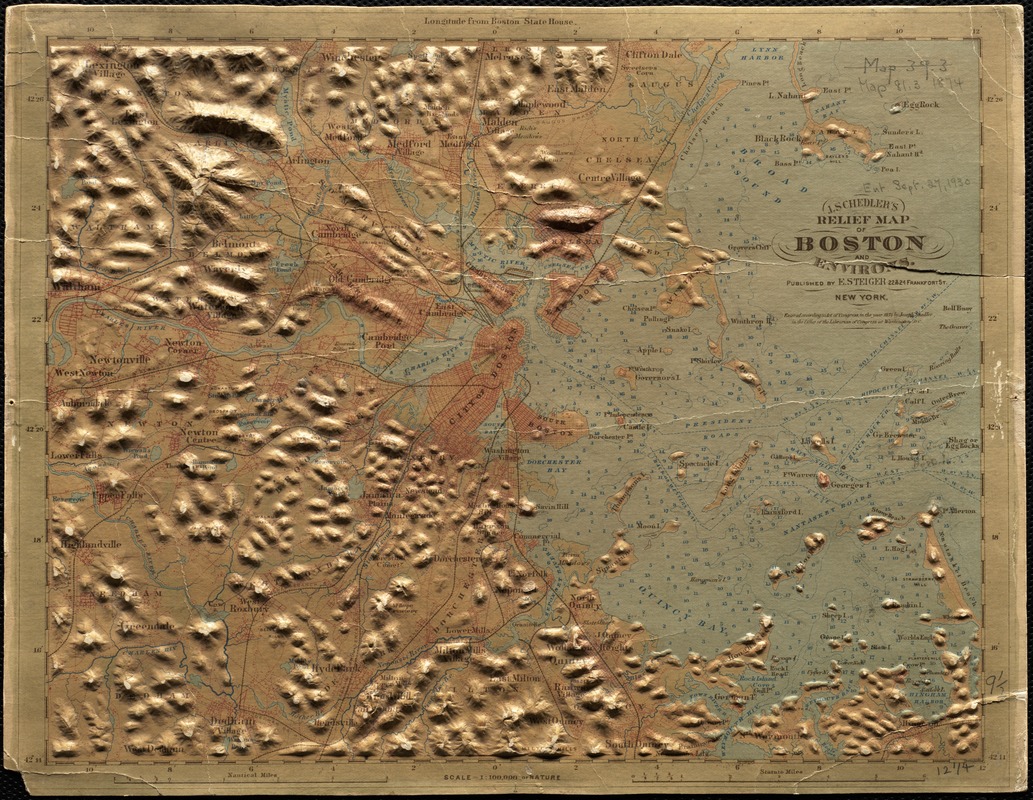

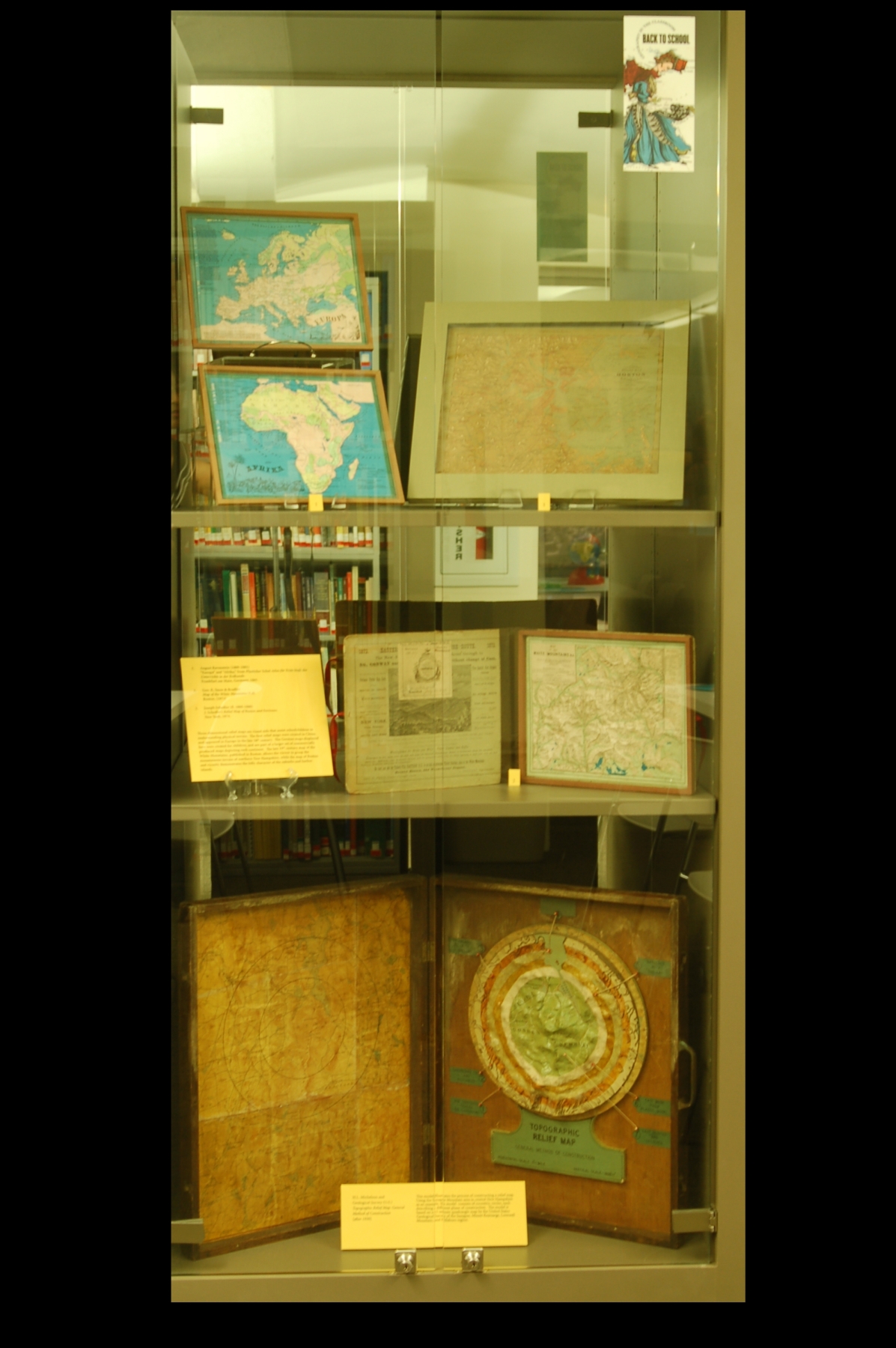

8. Relief Maps

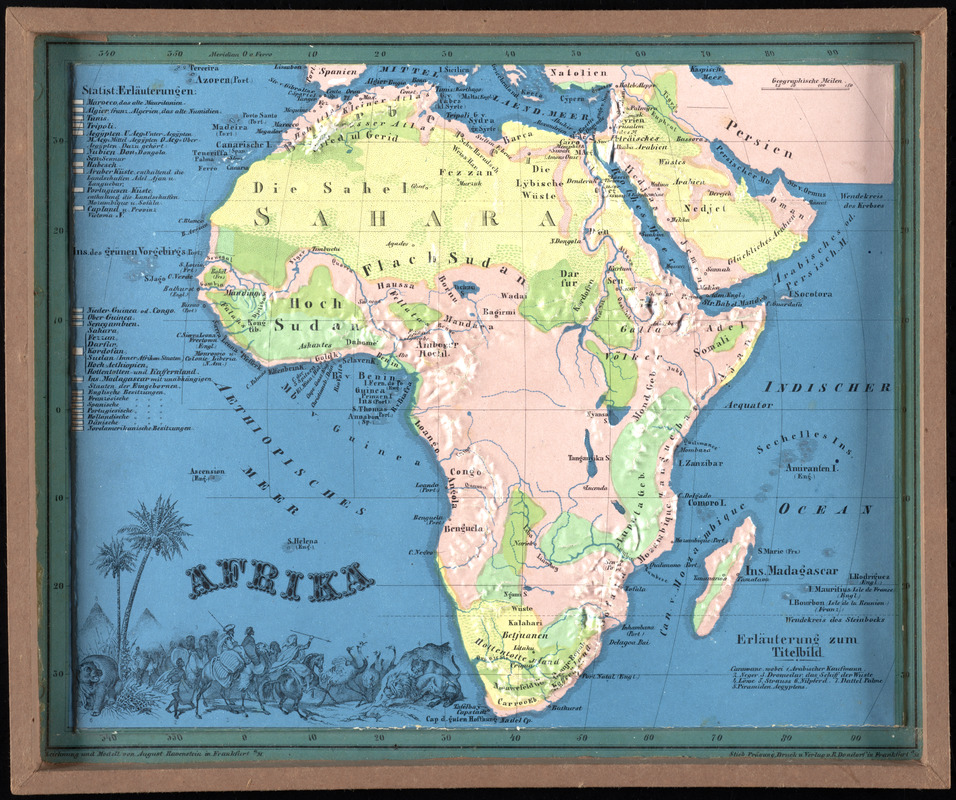

August Ravenstein

“Europa” and “Afrika,” from Plasticher Schul-Atlas für Erste Stufe des Unterrichts in der Erdkunde

Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1865.

Three-dimensional relief maps are visual aids that assist schoolchildren in understanding physical terrain. The first relief maps were created in China, and appeared in Europe in the late 18th century. The German maps displayed here were created for children, and are part of a larger set of commercially produced maps depicting each continent. The late 19th-century map of the White Mountains, published in Boston, allows the viewer to grasp the mountainous terrain of northern New Hampshire, while the map of Boston and vicinity demonstrates the hilly character of the suburbs and harbor islands.

9. In the Classroom

Gilman Joslin

Joslin’s six inch terrestrial globe, containing the latest discoveries

Boston, [1870s?].

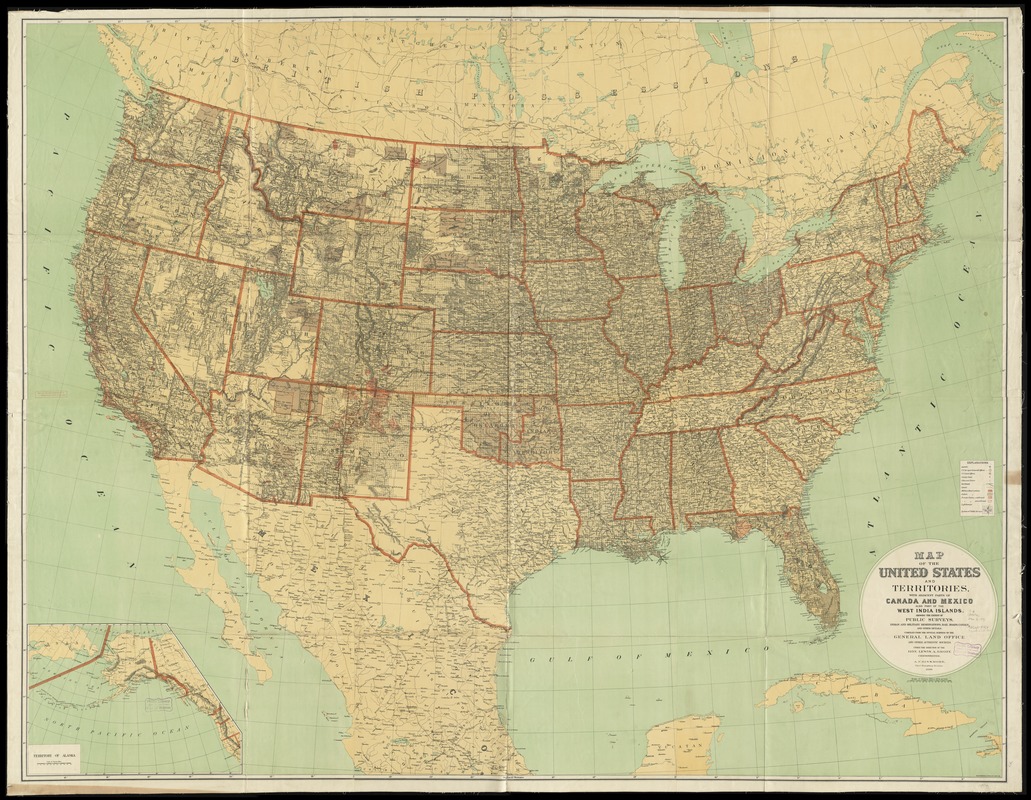

United States. General Land Office

Map of the United States and Territories with Adjacent Parts of Canada and Mexico, also Part of the West India Islands

Washington, D.C., 1890.

The items displayed here would have been found in a Boston public school classroom in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A Joslin globe was present in every classroom above the primary level in the city at the time. Maps, such as the example shown here, were also present in most classrooms of the time period.

Bibliography

Andrews, Jeanmarie. “Holding the World in Stitches.” Early American Life Apr. 2014: 54-57. [E162 .E214]

Blaisdale, Silas. Primary Lessons In Geography: Consisting Of Questions Adapted To Worcester’s and Woodbridge’s Atlases. Fourth ed. Boston: Marsh, Capen, and Lyon, 1832. [6283.53 No.1-10]

Bolton, Ethel Stanwood, and Eva Johnston. Coe. American Samplers. New York: Dover Publications, 1973. [NK9112 .B6 1973]

Boston (Mass.). School Committee. “School Document No. 3 – 1893: Expenditures for the Public Schools. Report of Committee on Accounts.” Documents of the School Committee of the City of Boston, for the Year 1893. Boston: Rockwell and Churchill, 1893. 59-60.

Burrowes, Thomas H., ed. The Pennsylvania School Journal. Vol. VI. Lancaster: W.B. Wiley, 1857.

Calhoun, Daniel H. “Eyes for the Jacksonian World: William C. Woodbridge and Emma Willard.” Journal of the Early Republic 4.1 (Spring, 1984): 1-26. [PER E164 .J68]

Course of Study in Geography, Nature Study and Elementary Science and Elementary Science. New York: Dept. of Education, 1907. [3597.328]

Crocker, Lucretia. Methods of Teaching Geography: Notes of Lessons. Second ed. Boston: Boston School Supply, 1884. [2289a.54]

Edmonds, Mary Jaene. Samplers & Samplermakers: An American Schoolgirl Art, 1700-1850. New York: Rizzoli, 1991. [FINE ARTS NK9112.E3 1991]

“Geographical Fun Atlas.” General Maps. Library of Congress. Web. 18 Apr. 2014. <http://www.loc.gov/collection/general-maps/articles-and-essays/#geographical-fun-atlas>.

Going To School in the 1820s. Barkhamsted: Clippership Publications, 2008.

“Maps of Great Smoky Mountains National Park.” Mapping the National Parks. Library of Congress. Web. 18 Apr. 2014. <http://www.loc.gov/collection/national-parks-maps/articles-and-essays/maps-of-great-smoky-mountains-national-park/>.

Millburn, John R. “Benjamin Martin and the Development of the Orrery.” The British Journal for the History of Science 6.4 (1973): 378-88. [PER Q125 .B77]

Norton, Mary Beth. Liberty’s Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women, 1750-1800. Boston: Little, Brown, 1980. [HQ1418 .N67]

Orbanes, Philip. The Game Makers: The Story of Parker Brothers from Tiddledy Winks to Trivial Pursuit. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School, 2004. [HD9993 .G354P376 2004]

Prescott, Edith. “Women’s Studies at Emma Willard School.” Women’s Studies Newsletter 8.1 (Winter, 1980): 7-8. [BPL online resource]

Report and Catalogue of the Boston Normal School for the Years 1890-1891. Rep. no. 5-1891. Boston: Rockwell and Churchill, 1891.

Ring, Betty. American Needlework Treasures. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1987. [TT753.R56 1987x]

Ring, Betty. Girlhood Embroidery. New York: Knopf, 1993. [FINE ARTS NK9112 .R57 1993]

Rittenhouse, David, and Smith, Dr. “A Description of an Orrery, Executed on a New Plan.” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 1 (Jan. 1, 1769-Jan. 1, 1771): 1-3. [BPL online resource]

Sargent, Emma Worcester, and Charles Sprague Sargent. Epes Sargent of Gloucester and His Descendants. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1923. [4432.440]

Schulten, Susan. “Emma Willard and the Graphic Foundations of American History.” Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007): 542-64.

Schulten, Susan. Mapping the Nation: History and Cartography In Nineteenth-Century America. Chicago: U of Chicago, 2012. [GA405.5 .S38 2012]

Schwartz, Harold. Samuel Gridley Howe; Social Reformer, 1801-1876. Cambridge: Harvard U, 1956. [HV1624.H7S35]

Stock, Phyllis. Better than Rubies: A History of Women’s Education. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1978. [LC 2031 .S76 1978]

Tyner, Judith. “Following the Thread: The Origins and Diffusion of Embroidered Maps.” Mercator’s World Mar.-Apr. 2001: 36-41. [PER GA101 .M47]

Tyner, Judith. “Geography Through The Needle’s Eye: Embroidered Maps and Globes In the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries.” Map Collector Spring 1994: 3-7.

Tyner, Judith. “Stitching the World: Westtown School’s Embroidered Globes.” Piecework Sept.-Oct. 2004: 28-31. [PER TT740.P54]

Tyner, Judith. “The World in Silk; Embroidered Globes of Westtown School.” Map Collector Spring 1996: 11-14.

Webster, Noah. “Education of Youth in the United States.” Early American Imprints, Series 2. American Antiquarian Society and NewsBank, Inc. Web. 2 Dec. 2013. <http://tinyurl.com/patqymp>.

Willard, Emma, and Ezra Brainerd. A Plan for Improving Female Education / by Emma Willard. And, Mrs. Emma Willard’s Life and Work in Middlebury. Marietta, GA: Larlin, 1987. [LC1756 .W65 1987]

“Yaggy`s Geographical Study Comprising Physical Political Geological and Astronomical Geography.” Boston Rare Maps. Boston Rare Maps. Web. 23 Apr. 2014. <http://www.bostonraremaps.com/catalogues/BRM1182.HTM>.

Credits

Stephanie Cyr

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center Staff

Lauren Chen, Cataloger

Alison Cody, Development and Program Manager

Stephanie Cyr, Assistant Curator of Maps

Ronald Grim, Curator of Maps

Michelle LeBlanc, Director of Education

Janet Spitz, Executive Director

Evan Thornberry, Reference and

Preservation Librarian

Catherine Wood, Office Manager

Graphic Design and Production

Framing and Matting

Andrew Leonard

Digital and Web Services

Tom Blake

Bahadir Kavlakli

Contributors to the Exhibition

Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Print Department

Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Rare Books and Manuscripts Department

Support generously provided by:

Martayan Lan & Augustyn, Inc.

Press

Leventhal Map Center

Museum Open House

Library highlights geography in education

The Huntington News, September 11, 2014

Boston-area to do list

Boston Globe, September 5, 2014