Introduction

In 1325, an island appeared on a nautical chart, just off the southwest coast of Ireland. This island, shrouded in mist, was said to appear once every seven years and was home to an advanced race that was immune to sickness and the passing of time. This mystical place, known variously as Brasil, Brazil, Breasil, Hy-Brasil, O’Brasil and numerous other names, would appear on maps for the next five centuries. Its exact location on maps would change over the years, and numerous expeditions would venture into the North Atlantic Ocean to find the island. Some mariners claimed to have discovered the legendary island; however, these reports teemed with fantastic accounts of alien beings, and eventually fell into legend.

In actuality, Hy-Brasil appears to derive from oral folklore and written literature from coastal Ireland, combined with geographic knowledge from early discovery. The western coast of Ireland is dotted with many rocks jutting out of the ocean. These numerous natural features, combined with optical illusions and other “tricks of the eye” could account for the presence of Hy-Brasil in the water, and its appearance on maps. However, the story of mythical islands including Hy-Brasil, and the legend of an Elysium or “Land of Youth” is part of the greater Irish-folklore belief in Tír na nÓg, or in English, “The Otherworld,” going back to ancient times.

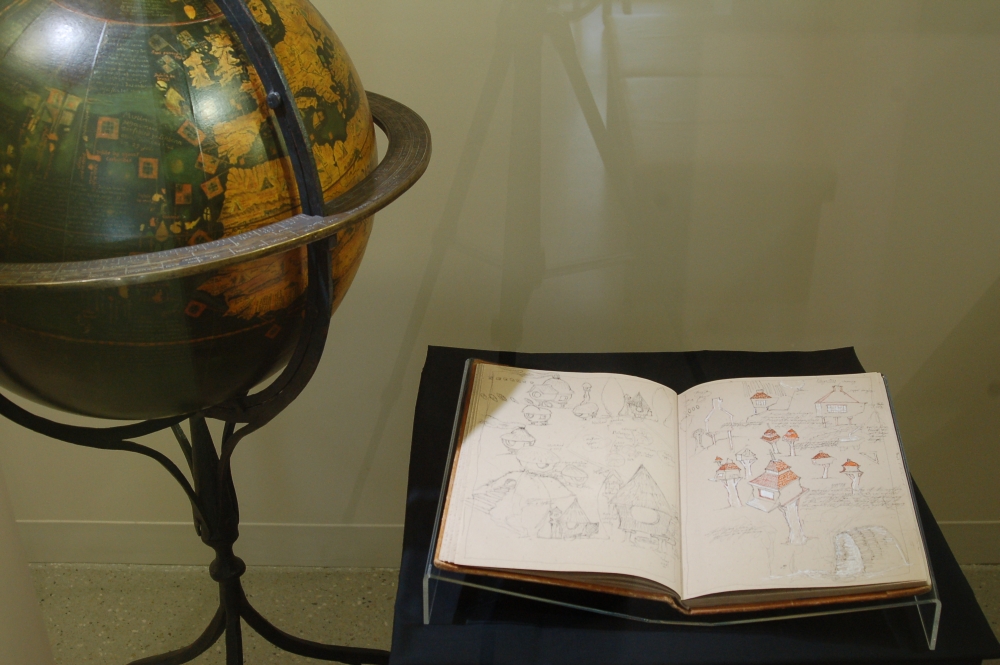

In this online exhibition of forty maps from the collection at the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library and the Mapping Boston Foundation, visitors will see the transition of Hy-Brasil over the course of five centuries from legitimate island destination, to “imaginary” place, to simply a “rock,” before it finally stops appearing on maps in the late 19th century. A variety of map formats are included in the online exhibition, such as portolan charts, woodcut engravings, copperplate engravings and lithographic prints. Hy-Brasil even makes an appearance on a 1492 globe.

In addition, several sketch books and drawings of internationally acclaimed visual artist Caoimhghin Ó Fraithile (Quee-veen Ó Frá-ha-la) (Ireland) will be on display in the Leventhal Map Center gallery from late June-October 2016. Mr. Ó Fraithile’s intricate drawings echo maps found in the collection and invite us to visit the forgotten or hidden lands and places that inhabit our collective imagination. His sketchbooks, however, illustrate images of his site-specific floating artwork entitled “South of Hy-Brasil,” a three-dimensional piece that will be sited in the lagoon behind the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, from late summer through mid-October 2016. His floating work is part of Tír na nÓg, a temporary public art project in the Fenway section of the Emerald Necklace park system. The project also features “The Well House,” a sculptural work by artist Michael Dowling (Boston/Ireland). Tír na nÓg is a fitting name for this temporary art project, as both of these artists explore art as a threshold to otherworldliness and back again.

The outdoor artworks by Mr. Ó Fraithile and Mr. Dowling are part of Ireland’s 2016 Centennial – a global initiative to mark the centenary of the 1916 Easter Rising which set Ireland on its path for independence. Boston is the only U.S. city hosting temporary public art projects to commemorate the 1916 Centennial. These works will also celebrate the 2016 Centennial of the National Park System of which the Emerald Necklace is part. Tír na nÓg, and its related exhibitions and events, are supported by Culture Ireland as part of the Ireland 2016 Centenary Programme. Medicine Wheel Productions is the lead organization for Tír na nÓg and their Cultural Partner is the Fenway Alliance. Additional key supporters of the project are Mayor Martin J. Walsh, the Consulate General of Ireland in Boston, and Boston Parks and Recreation. To learn more about Medicine Wheel and Tír na nÓg, or to see a full listing of project sponsors and collaborators, please visit: http://mwponline.org/wordpress/projects/tir-na-nog/

Please take the Culture Ireland 2016 Centenary Survey to provide feedback on this exhibition http://bit.ly/1sLfBWC

1. Early Depictions of Brasil

Angellino Dulcert (fl. 1339)

[Carte marine de la mer Baltique, de la mer du Nord, de l’océan Atlantique Est, de la mer Méditerranée, de la mer Noire et de la mer Rouge]

1339. Facsimile, 1890.

The island of Hy-Brasil first appeared on a hand-drawn nautical chart in the year 1325. This chart, by Majorcan cartographer Angelino Dulcert, depicted Hy-Brasil as a large, circular landmass off the western coast of Ireland. Displayed here is a 19th-century facsimile of Dulcert’s chart from 1339 – fourteen years after the island originally graced the chart. Early depictions of Hy-Brasil on maps place the island near the western coast of Ireland, nearly at the latitude of southern Ireland. However, as time passes and more sea-faring expeditions by Europeans take place, the mapped location of Hy-Brasil changes.

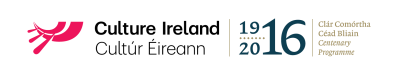

Martin Behaim (1459-1507)

Facsimile von Martin Behaim’s 1492 ‘Erdapfel’

Leipzig, 1992.

Courtesy Mapping Boston Foundation.

Hy-Brasil is included in this facsimile of Martin Behaim’s famous globe, originally produced in 1492. Here, the island sits just off the coast of southwest Ireland. Just five years after Behaim made his globe in Germany, the English navigator John Cabot sailed out of Bristol in search of the fabled island. Cabot did make landfall in Newfoundland in 1497, and soon news circulated that he had indeed found the elusive Brasil island. By the mid-16th century, Hy-Brasil is depicted as being in American waters, off the coast of Newfoundland.

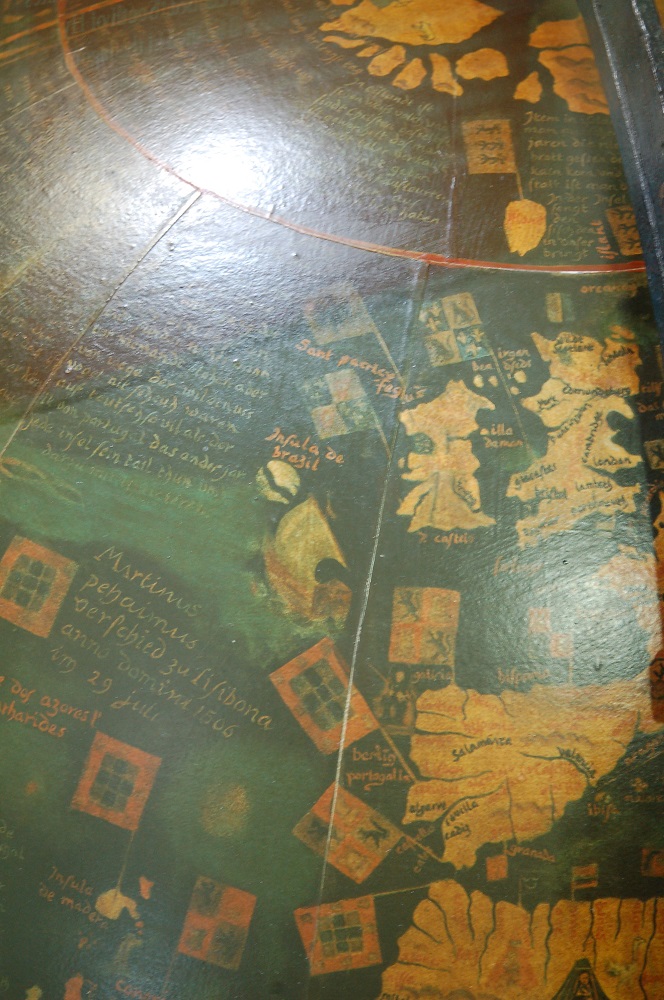

Claudius Ptolemy (2nd Century CE)

Oceani Occidetalis seu Terre Nove Tabula

Strasbourg, France, 1525.

The 1525 edition of Ptolemy’s Geographia, published in Strasbourg, includes a depiction of Hy-Brasil in the map of the Atlantic, or “western,” Ocean. Geographia included maps from the ancient world of Ptolemy, as well as modern maps produced as the result of recent expeditions. This map of the Atlantic Ocean is an example of a modern map in the atlas. Indicated as “Brazil” in this woodcut map, the island is represented as two triangular shapes, pressed back-to-back, with space in between. Although the island is still near the south western coast of Ireland, its shape has changed from earlier depictions. Later maps from the 16th century reveal that Hy-Brasil moves closer to American waters, mainly east of Newfoundland.

Paolo Forlani (fl. 1560-1571)

Il Desegno del Discoperto della Noua Franza …

Venice, 1566. Facsimile, 1892.

By 1566, Hy-Brasil has been relocated from the western coast of Ireland, to the southern coast of Labrador, in North America. Here, Italian map maker Paolo Forlani places Hy-Brasil just southeast of the coast of Labrador in his map of “Noua Franza,” or, New France (Canada). There are a number of maps in this online exhibition that feature a similar placement of Brasil in American waters.

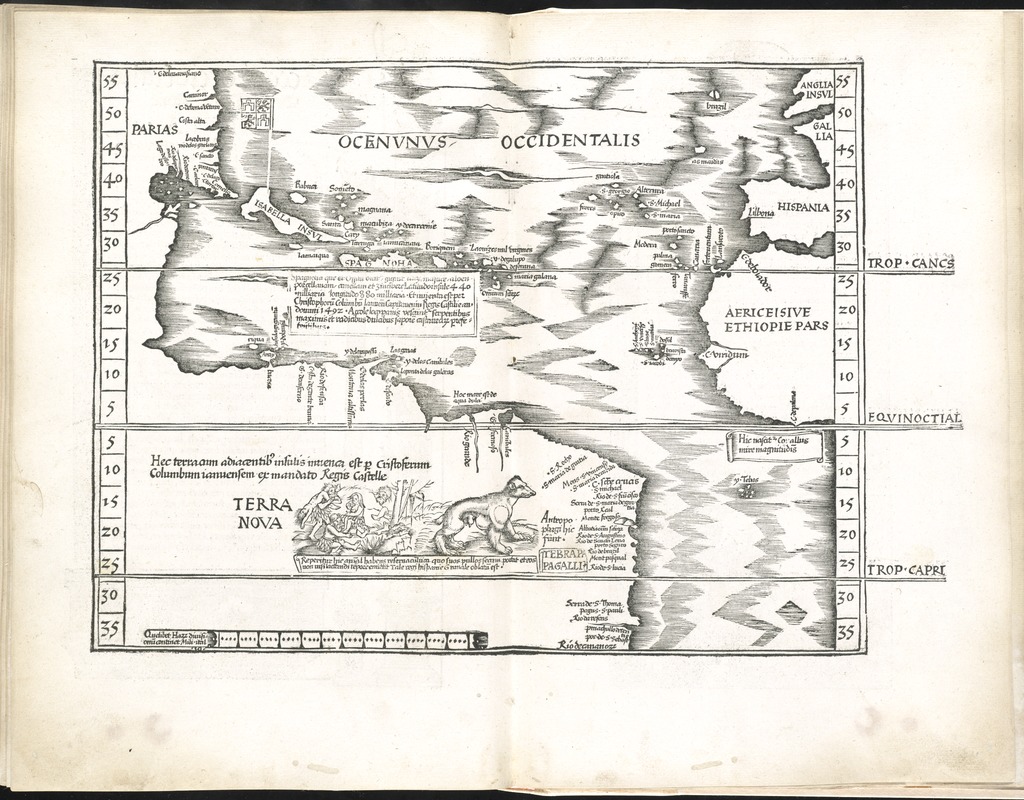

Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598)

“Typus Orbis Terrarum,” from Theatrum Orbis Terrarum

Antwerp, Belgium, 1570.

Abraham Ortelius’ atlas Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, or, Theater of the World, is considered the first modern world atlas. It was the first time that a set of maps, contemporary to the date of publication, was designed, drawn, and engraved with the intention of publishing them in a bound volume. Ortelius includes Hy-Brasil in three maps in the atlas – the world map, the map of Europe, and the map of Northern Europe – and places the island in the vicinity of Ireland. 16th-century mapmakers prior to Ortelius placed Hy-Brasil in American waters; however, in this example, Ortelius returns the mythical island to its original position near to Ireland.

Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598)

“Europae,” from Theatrum Orbis Terrarum

Antwerp, Belgium, 1570.

In Ortelius’ map of Europe from Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, he places Hy-Brasil off the northwestern coast of Ireland – a marked difference from the positioning of Hy-Brasil in the world map from the same atlas.

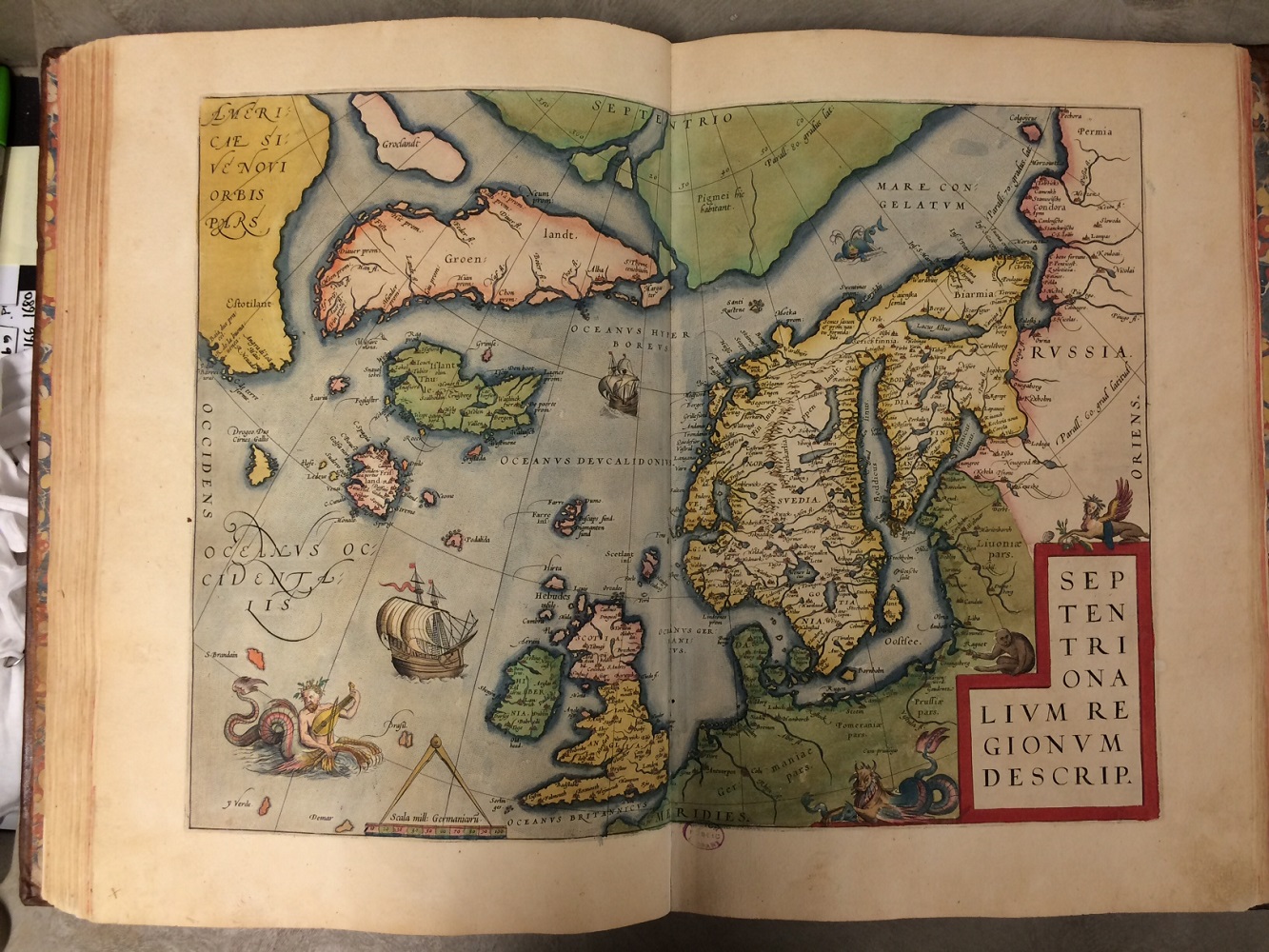

Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598)

“Septentrionalium Regionum Descrip.,” from Theatrum Orbis Terrarum

Antwerp, Belgium, 1570.

Ortelius includes Hy-Brasil in a third map from his Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. In this map of Northern Europe, Ortelius places Hy-Brasil off the western coast of Ireland, and depicts the island in a similar style as was seen in the 1525 edition of Ptolemy above. In addition, the mythical island of St. Brandan is included in this map. The story of St. Brendan also comes from Irish folklore, although its presence on maps was short-lived compared to that of Hy-Brasil.

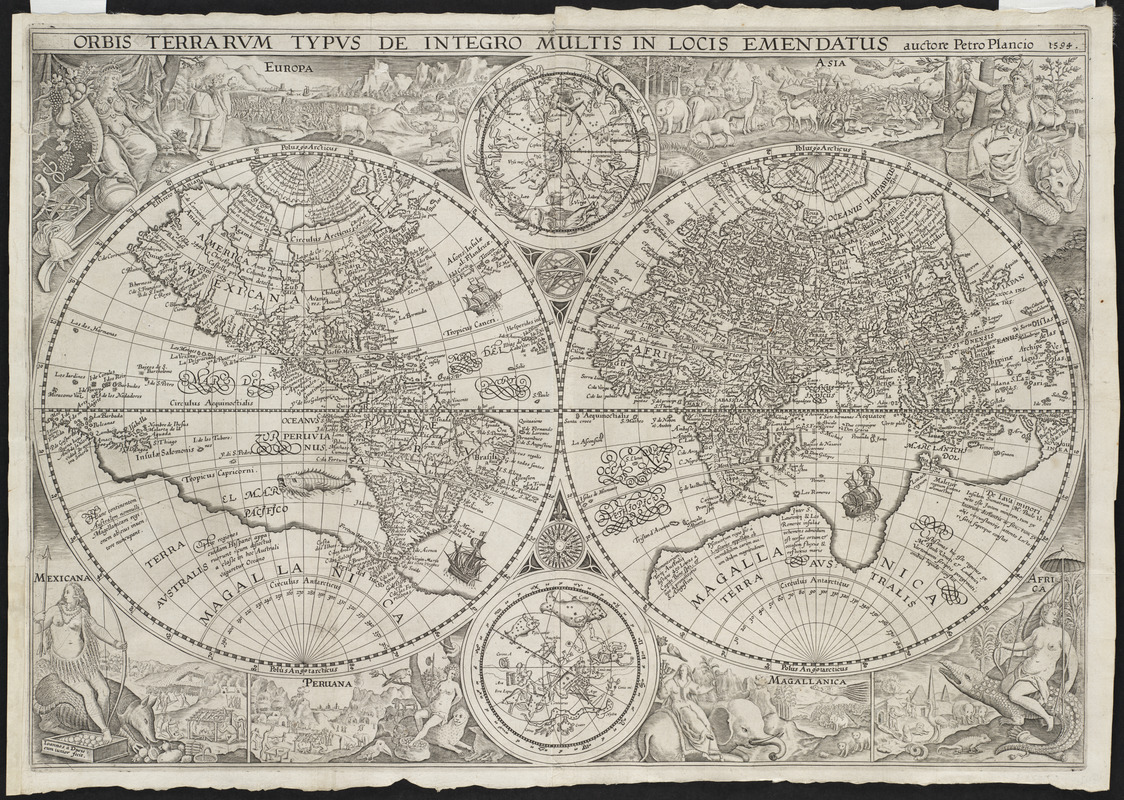

Petrus Plancius (1552-1622)

Orbis Terrarum Typus de Integro Multis in Locis Emendatus

Amsterdam, 1594.

Courtesy Mapping Boston Foundation.

In this double-hemisphere map of the world by Petrus Plancius, Hy-Brasil assumes its original position off the western coast of Ireland. The additional maps executed in this format included here also keep Hy-Brasil in the eastern hemisphere, near Ireland.

2. 17th Century – Maps of the World and America

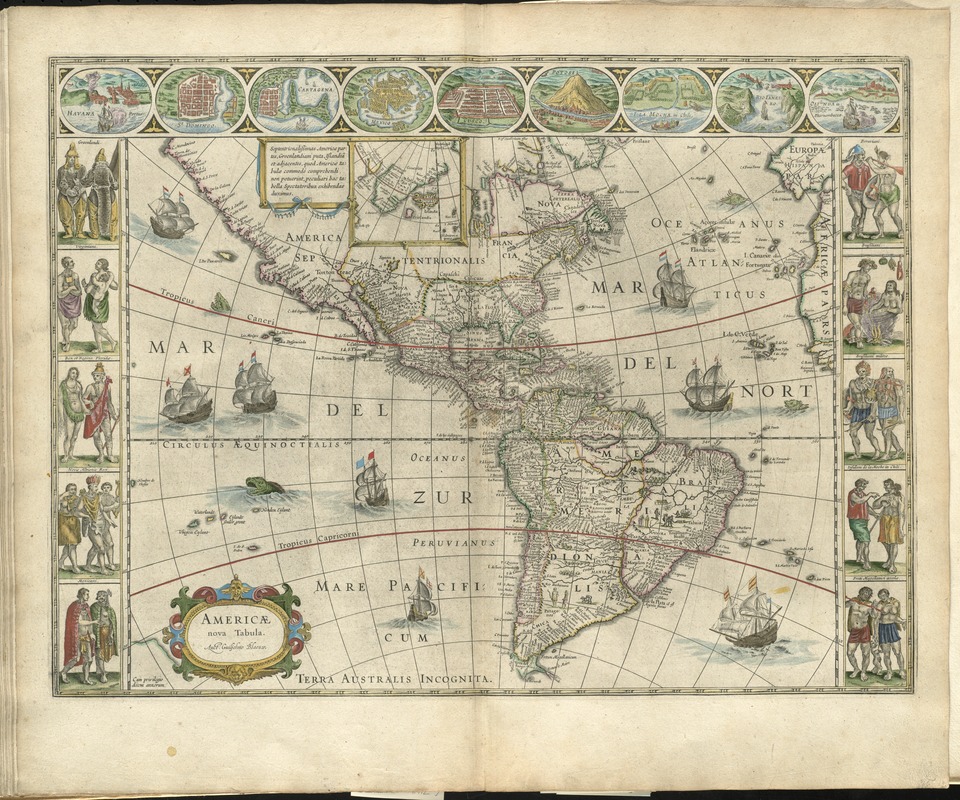

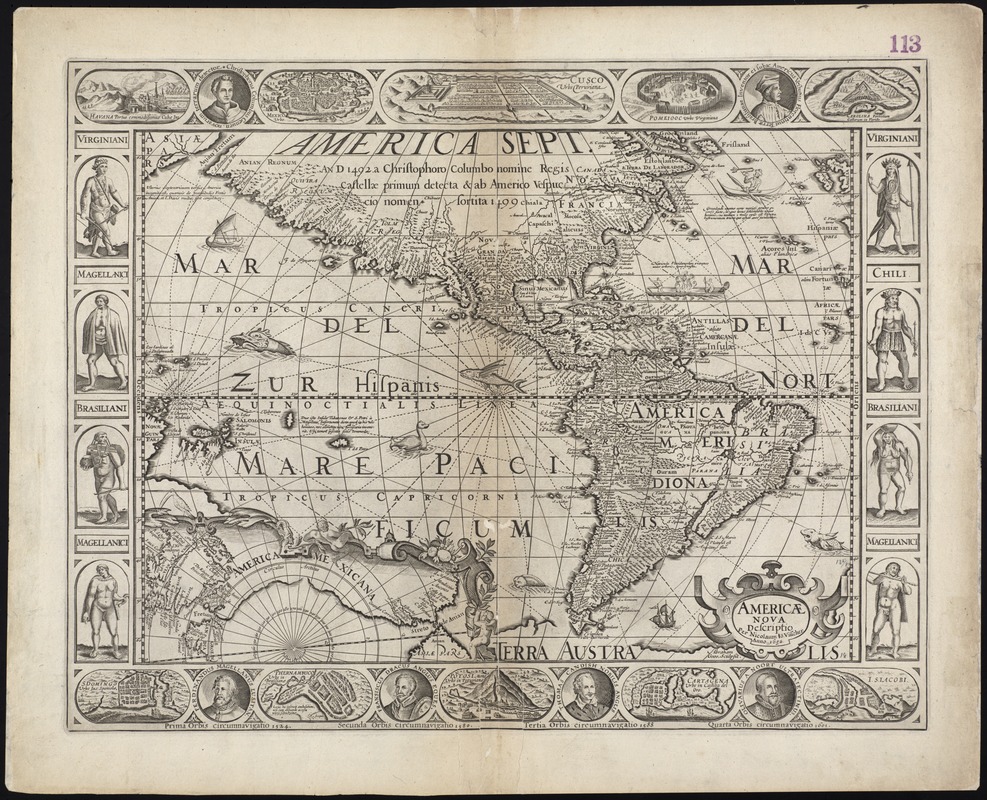

Jodocus Hondius (1563-1612)

America

Amsterdam, [between 1609 to 1633]

Early 17th-century maps of the Americas also included Hy-Brasil, although the Island is most often depicted in Irish waters. In his map of America published circa 1609, Jodocus Hondius provides reference to the far western parts of the European continent by including the countries of Ireland, England and Portugal. Hondius also includes an illustration of a navigator from Greenland near the Island of Brasil and describes his sailing vessel and equipment, while pointing his trident towards a sea-bird off the coast of Scotland.

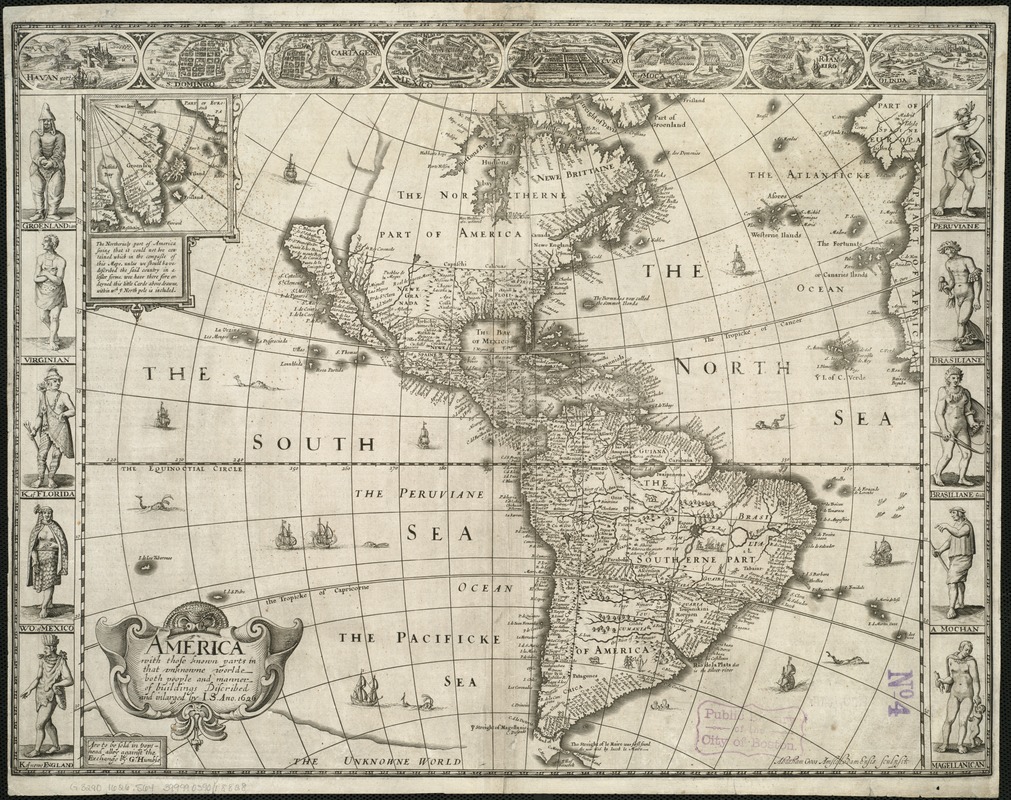

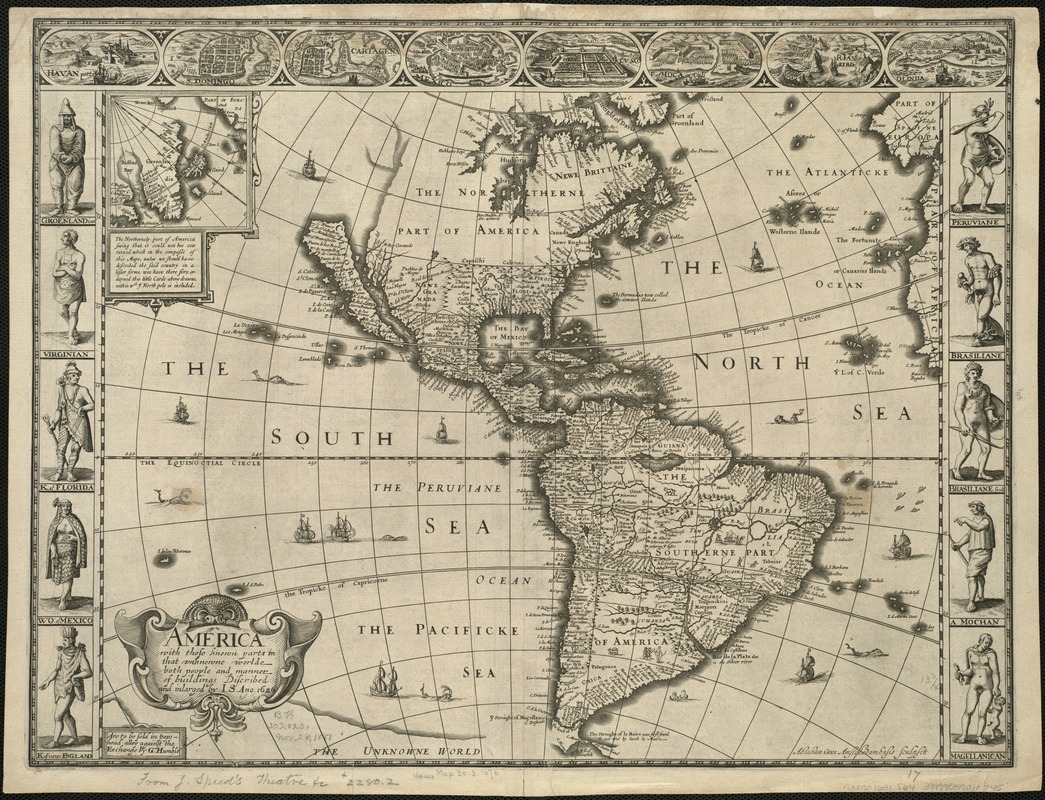

John Speed (1552?-1629)

America with Those Known Parts in That Unknowne Worlde Both People and Manner of Buildings

London, 1626.

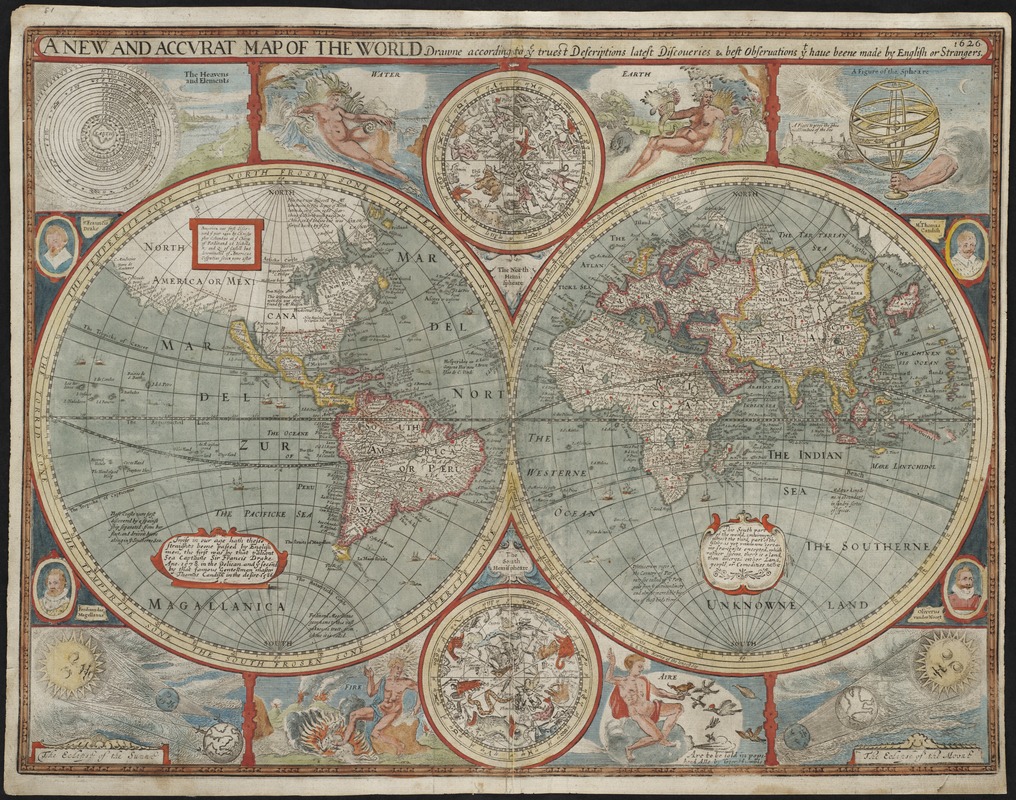

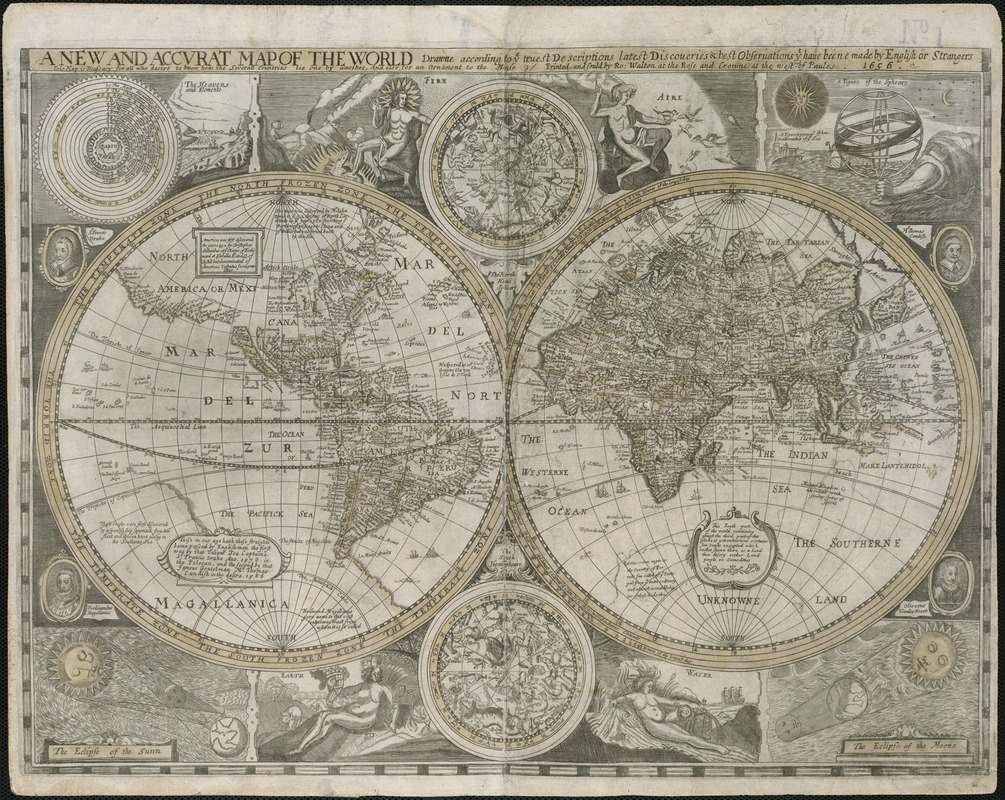

John Speed (1552?-1629)

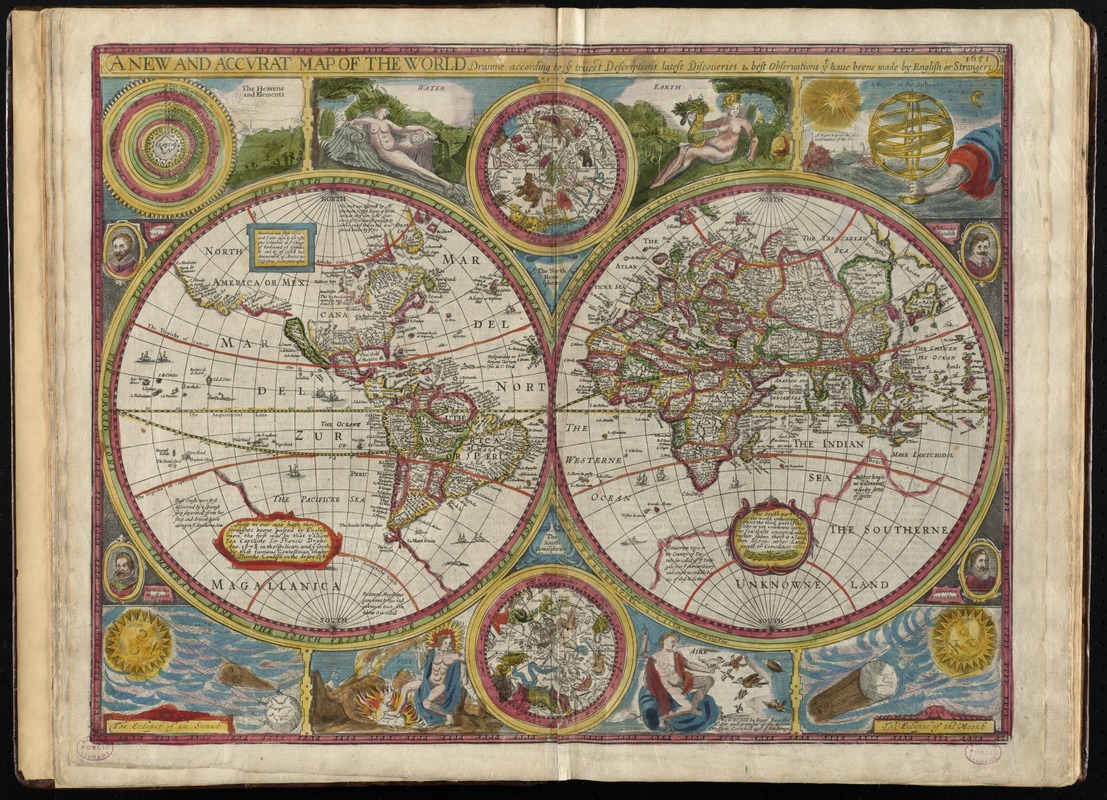

A New and Accurat Map of the World, Drawne According to ye Truest Descriptions Latest Discoveries & Best Observations yt Have Beene Made by English or Strangers, 1626

[London, 1627]

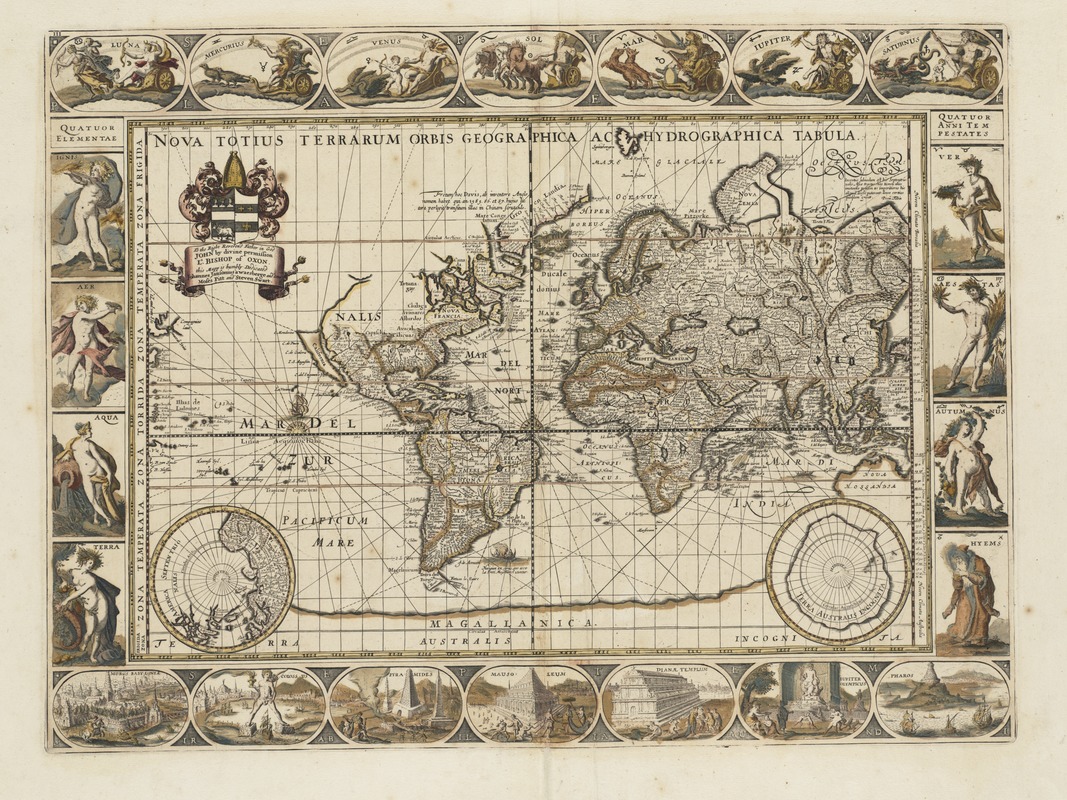

Hendrik Hondius (1597-1651)

Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Geographica ac Hydrographica Tabula

Amsterdam, 1630.

John Speed (1552?-1629)

America with Those Known Parts in that Unknowne Worlde both People and Manner of Buildings

London, 1631.

Matthaeus Merian (1593-1650)

America Nouiter Delineata

[Frankfurt, Germany, 1634]

17th-century maps of the world, executed on the Mercator projection, also include the island of Hy-Brasil, such as this 1634 map by Swiss cartographer Matthaeus Merian. Here, Hy-Brasil is positioned in its original area near southwest Ireland. The same is true for Blaeu’s world map from 1638 included below.

Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1571-1638)

Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Geographica ac Hydrographica Tabula

Amsterdam, 1638.

Courtesy Mapping Boston Foundation.

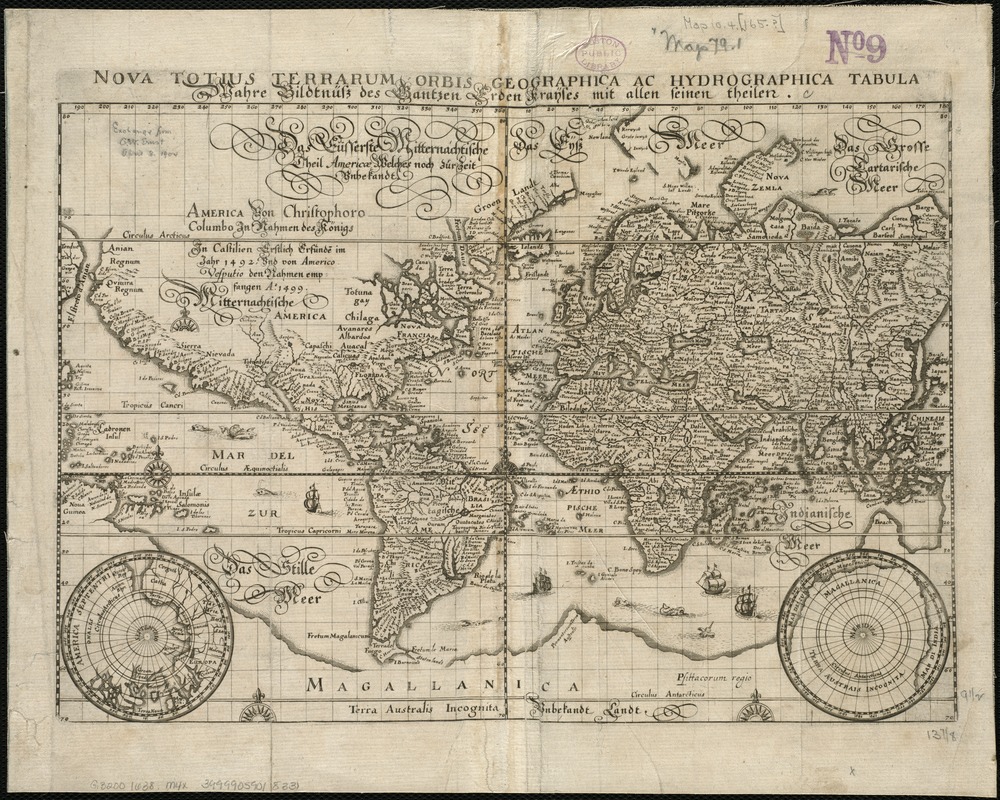

Matthaeus Merian (1593-1650)

Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Geographica ac Hydrographica Tabula = Wahre Biltnüss des Gantzen Erden Kraÿses mit Allen Seinen Theilen

[Germany?, 1638]

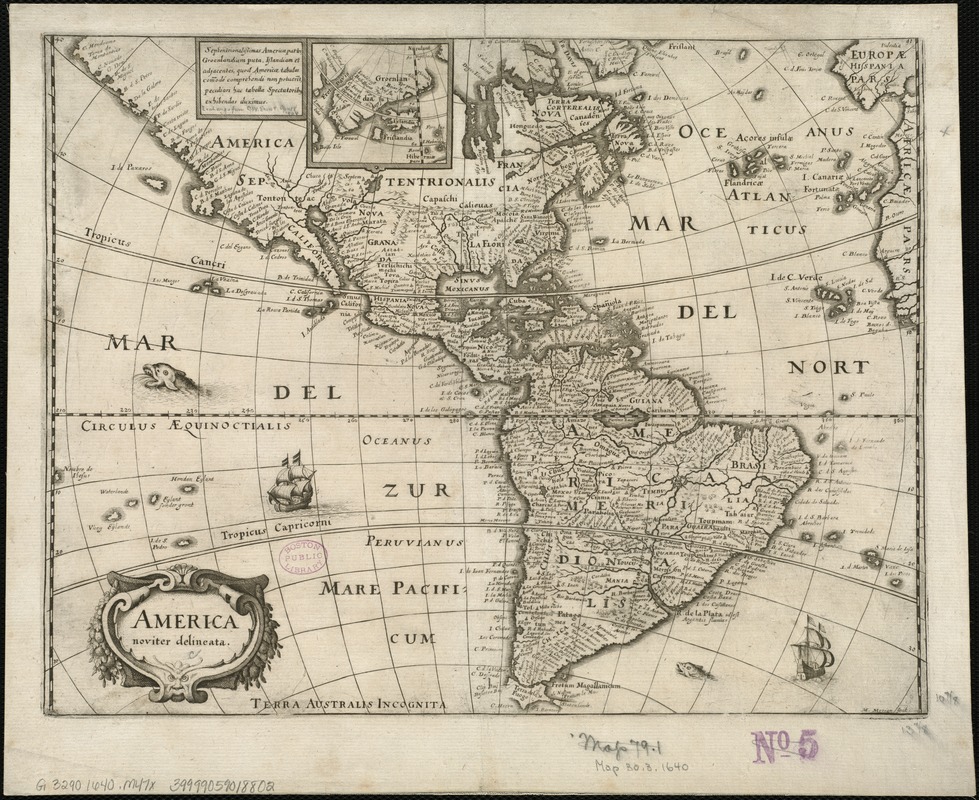

Matthaeus Merian (1593-1650)

America Noviter Delineata

[Germany?, 1640?]

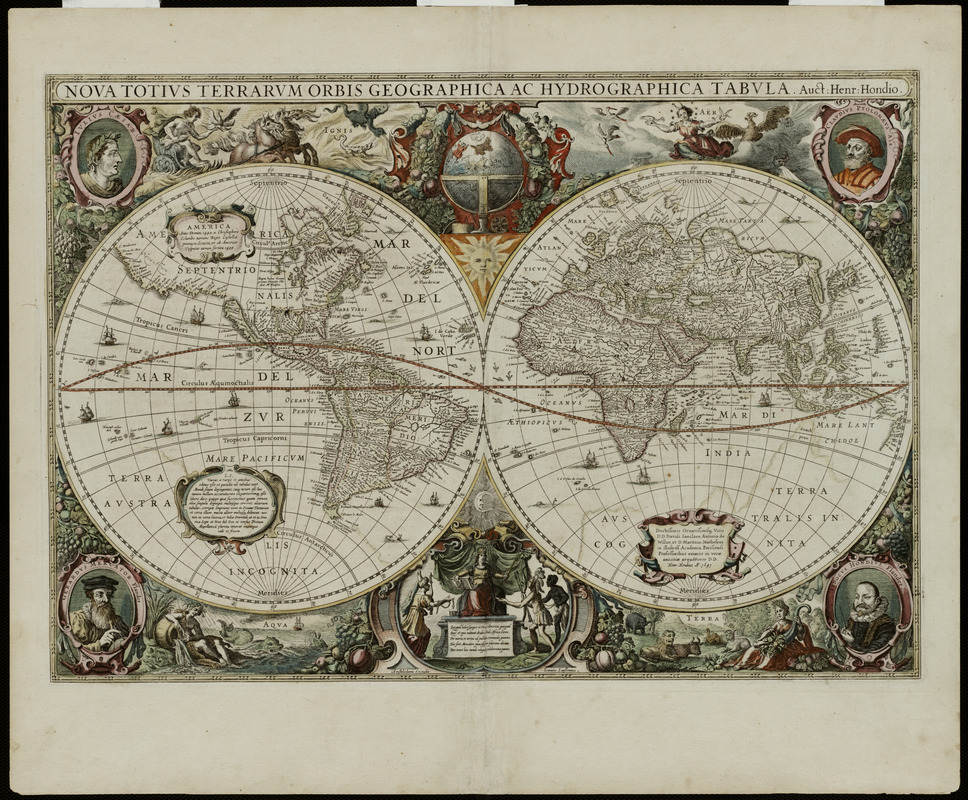

Hendrik Hondius (1597-1651)

Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Geographica ac Hydrographica Tabula

[Amsterdam, 1641]

Courtesy Mapping Boston Foundation.

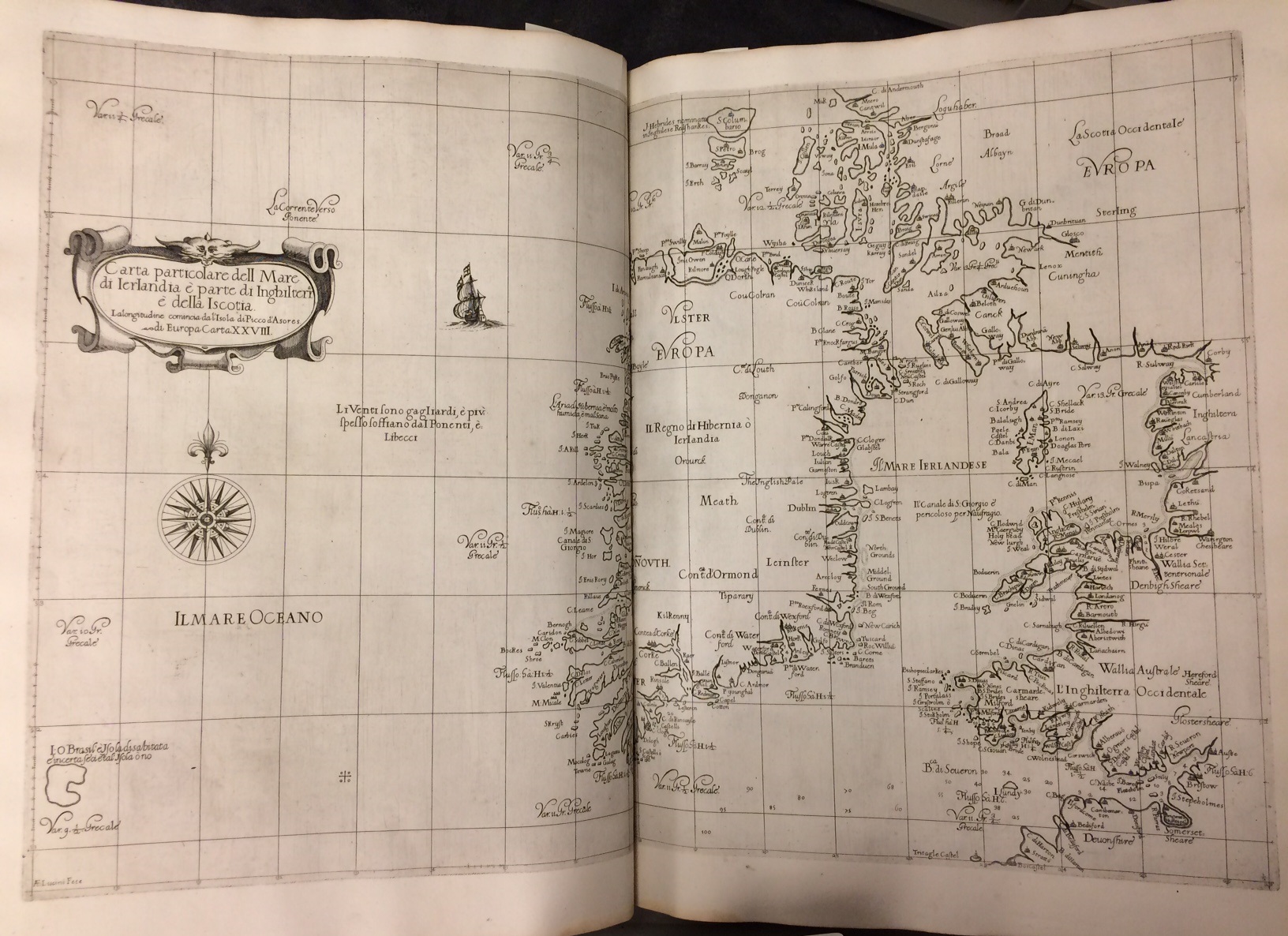

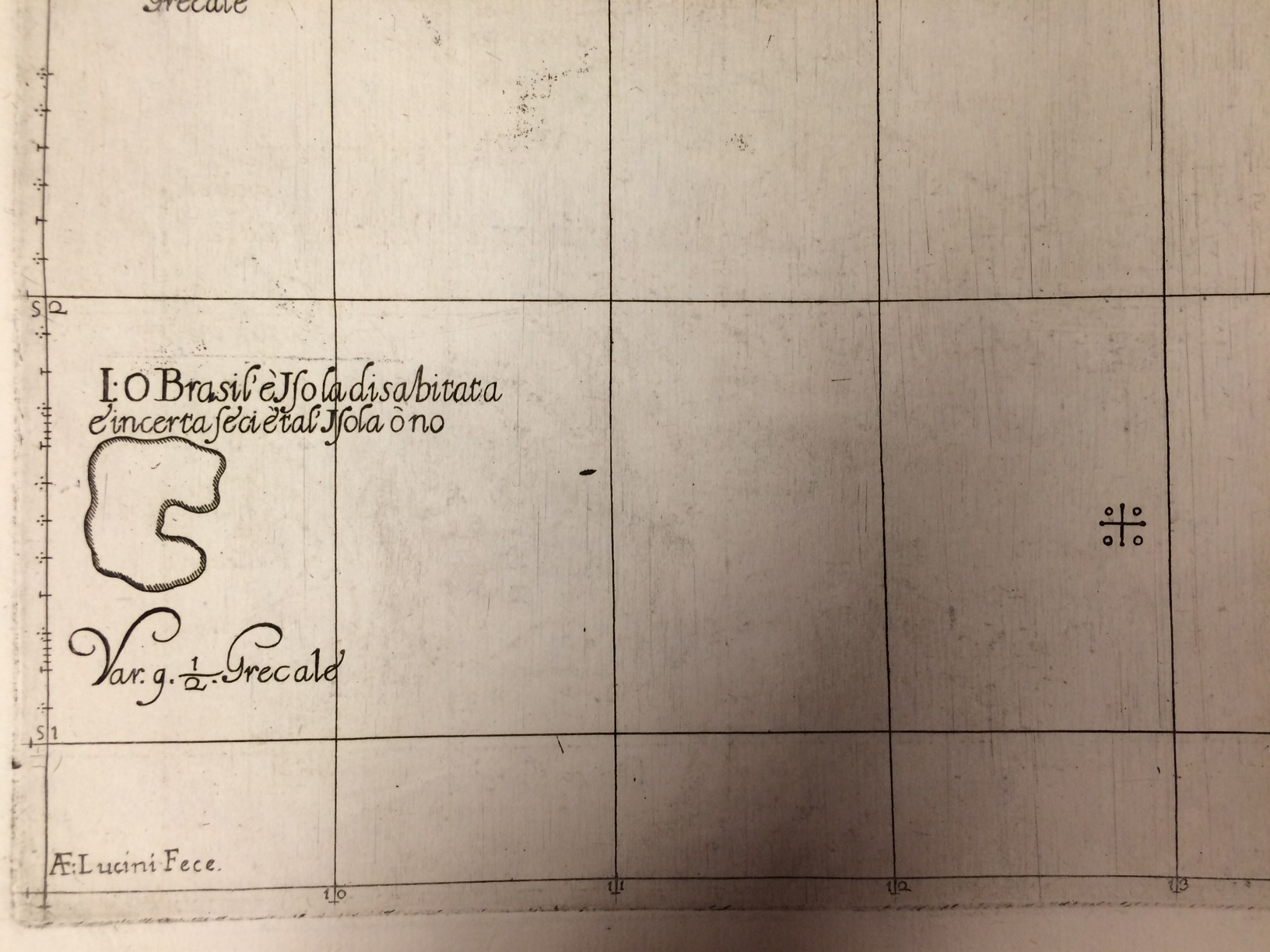

Robert Dudley (1574-1649)

“Carta Particolare dell Mare di Ierlandia é Parte di Inghilterr é della Iscotia,” from Dell’arcano del Mare

Florence, 1646-47.

Robert Dudley’s navigational atlas Dell’arcano del Mare was the first sea atlas to include charts from the entire known world. In his map of Ireland and the western coast of England, he includes Hy-Brasil, along with the following description: “I.O Brasil è Isola disabitata è incerta secietal’ Isola ò no.” In English, this phrase roughly translates to “Island [of] O Brasil. Island is uninhabited; is uncertain [friendly] island or not.” Here, Dudley states that Hy-Brasil is indeed in the North Atlantic Ocean, and is uninhabited, but is unsure of whether there is a “friendly society” living on the island. The shape of the island has changed yet again, and is represented here as a horseshoe, or an atoll [a ring-shaped coral reef]. Hy-Brasil executed in this shape was first depicted on a Catalan map of 1375.

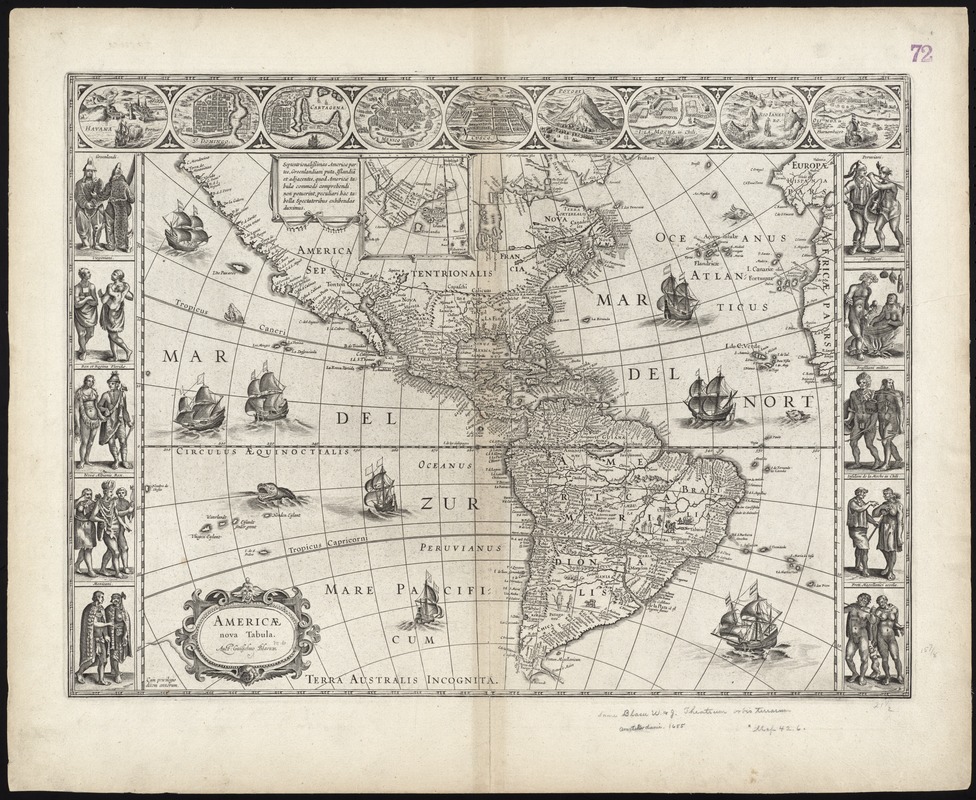

Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1571-1638)

Americae Nova Tabula

[Amsterdam, 1650]

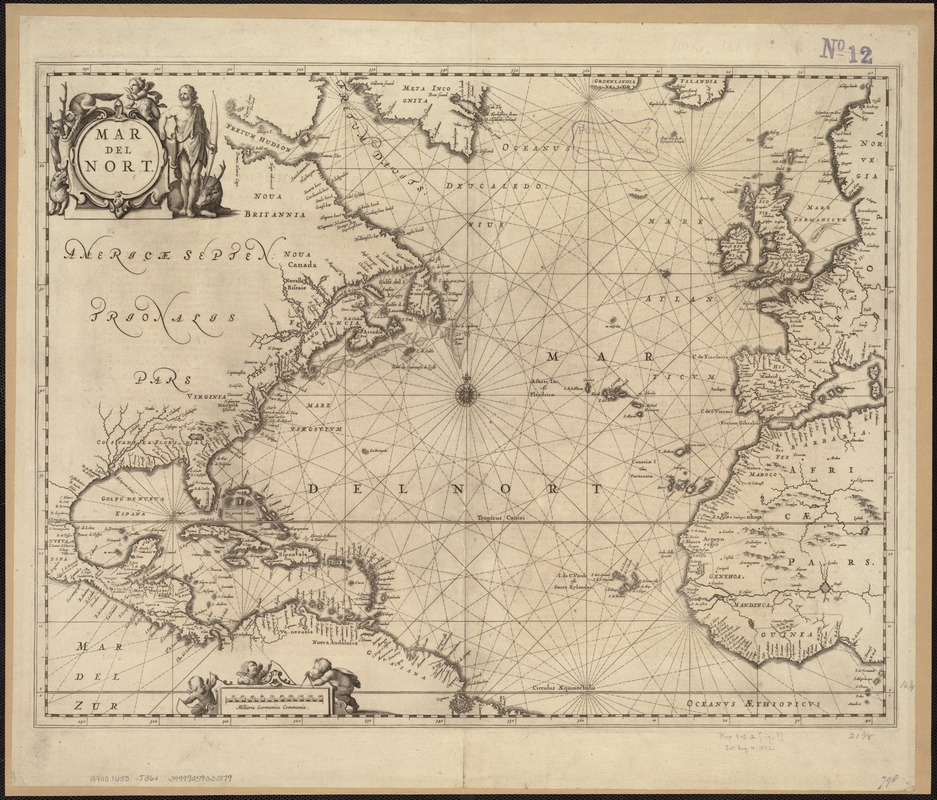

Jan Jansson (1588-1664)

Mar del Nort

Amsterdam, 1650.

Nicholaes Visscher (1649-1702)

Americae Nova Descriptio

Amsterdam, 1652.

Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1571-1638)

Americae Nova Tabula

Amsterdam, 1655.

John Speed (1552?-1629)

A New and Accurat Map of the World Drawne According to ye Truest Descriptions Latest Discoveries & Best Observations yt Have Beene Made by English or Strangers

London, 1656.

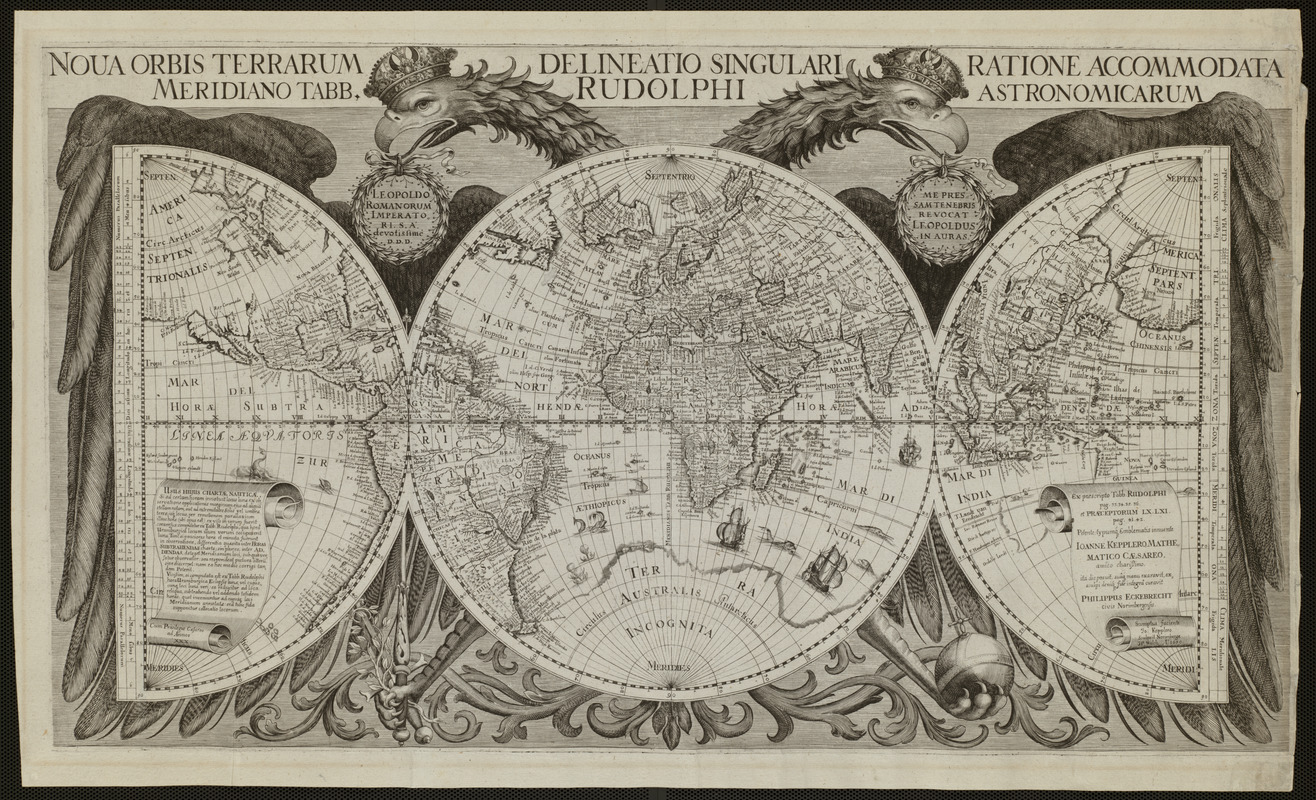

Philipp Eckebrecht (1594-1667)

Nova Orbis Terrarum Delineatio Singulari Ratione Accommodata Meridiano tabb. Rudolphi Astronomicarum

[Ulm, Germany, 1658?]

This 17th-century map by German merchant Philipp Eckebrecht includes a number of unique features. The world is portrayed by one full circle, or hemisphere, flanked by two half-circles, which is an unusual presentation. The prime meridian of the full circle runs through Uraniborg, Sweden, the site of astronomer Tycho Brahe’s observatory, while the double-headed eagle represents the Holy Roman Empire, which was in power at the time the map was produced. Eckebrecht’s map contains a number of references to contemporary figures and politics, however, he also indicated the presence of mythical “Brasil” to the west of Ireland.

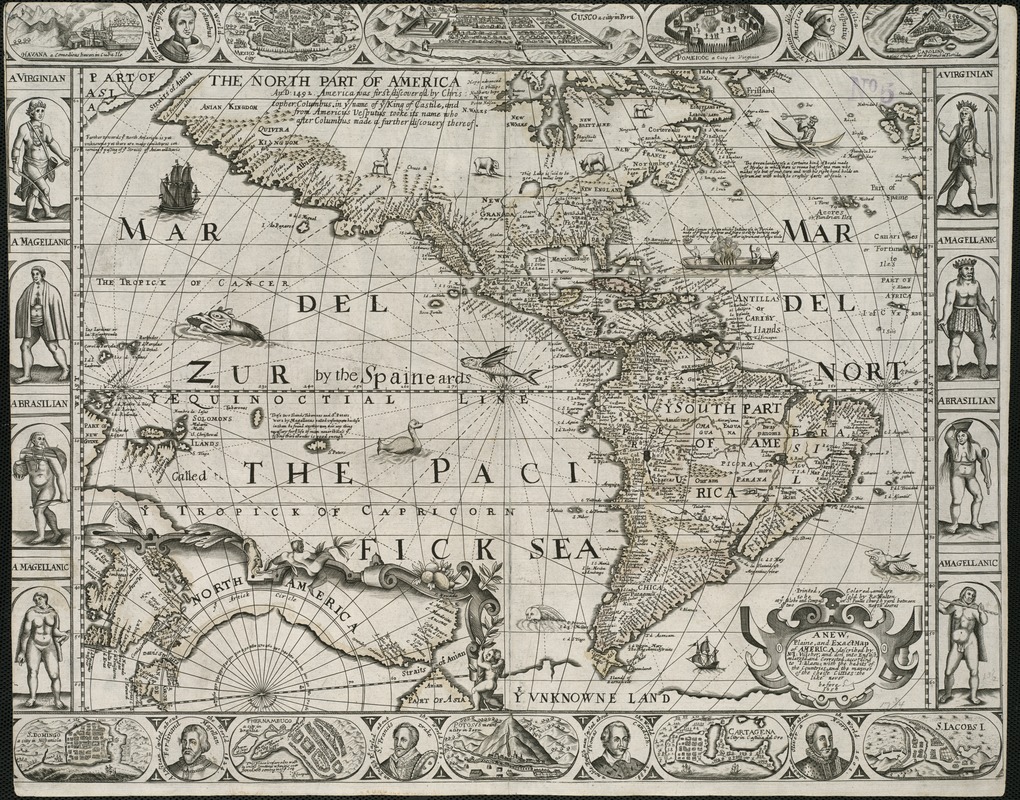

Nicholaes Visscher (1649-1702)

A New, Plaine, and Exact Map of America Described by N.I. Visscher, and don into English, Enlarged, and Corrected, according to I. Blaeu, with the Habits of the Countries, and the Manner of the Cheife Citties, the Like Never Before

London, 1658.

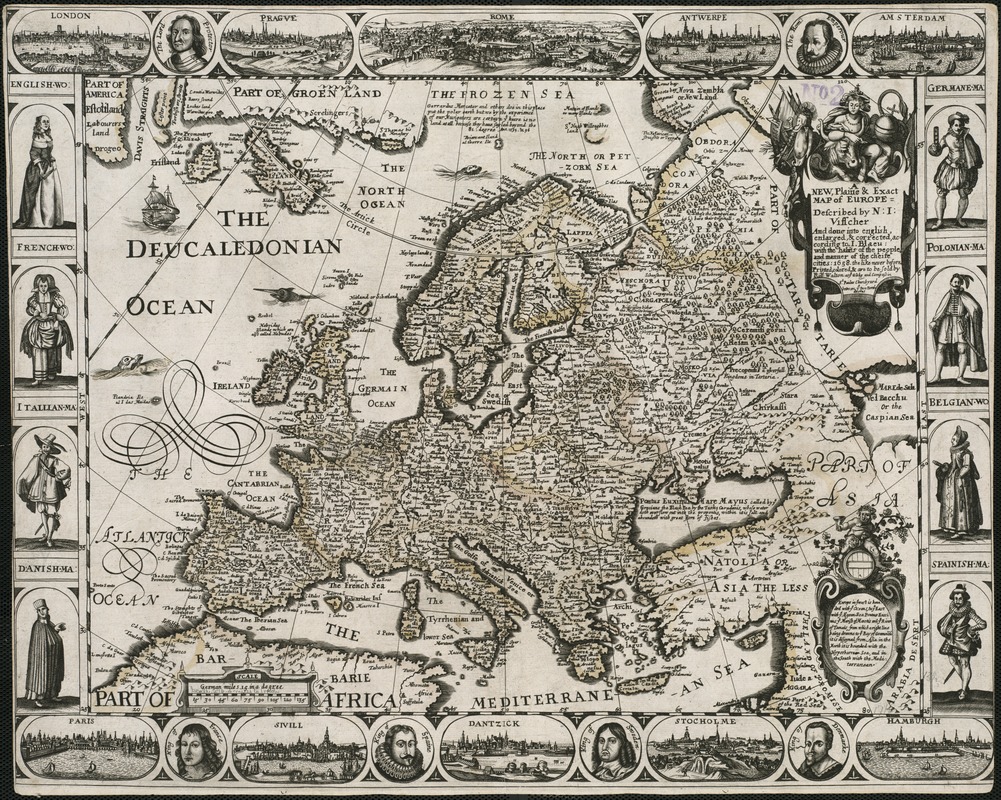

Nicholaes Visscher (1649-1702)

A New, Plaine & Exact Map of Europe, Described by N.I. Visscher and Done into English, Enlarged & Corrected According to I. Blaeu, with the Habits of the People, and Manner of the Cheife Cities, 1658, the Like Never Before

London, 1658.

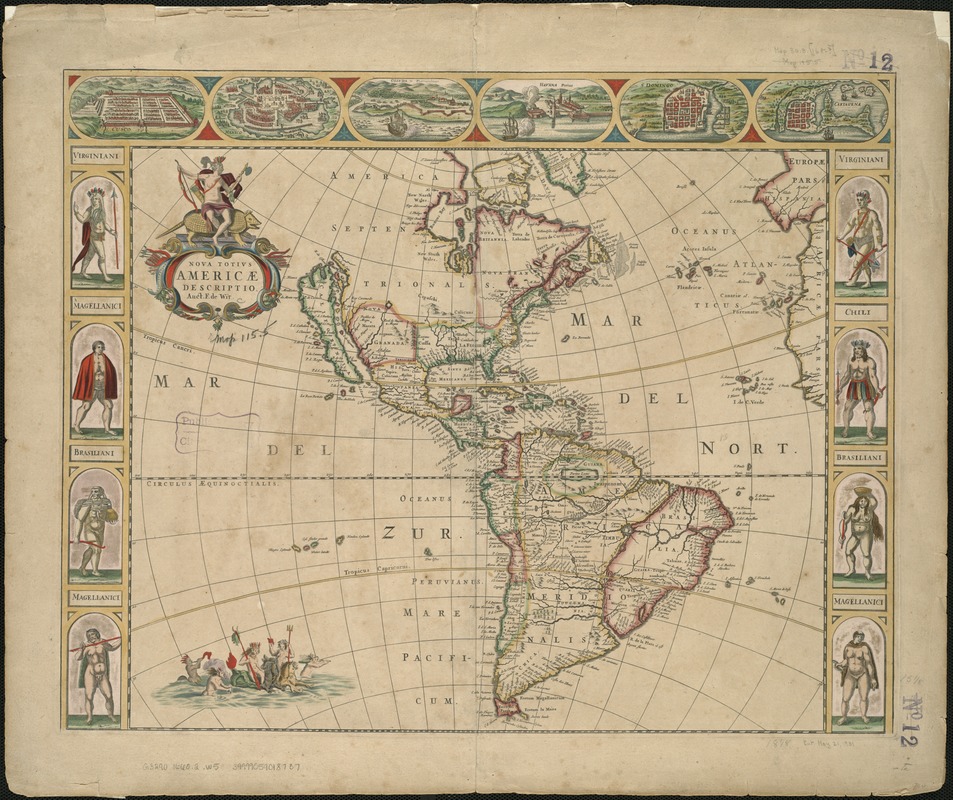

Frederik de Wit (1629 or 1630-1706)

Nova Totivs Americae Descriptio

Amsterdam, 1660.

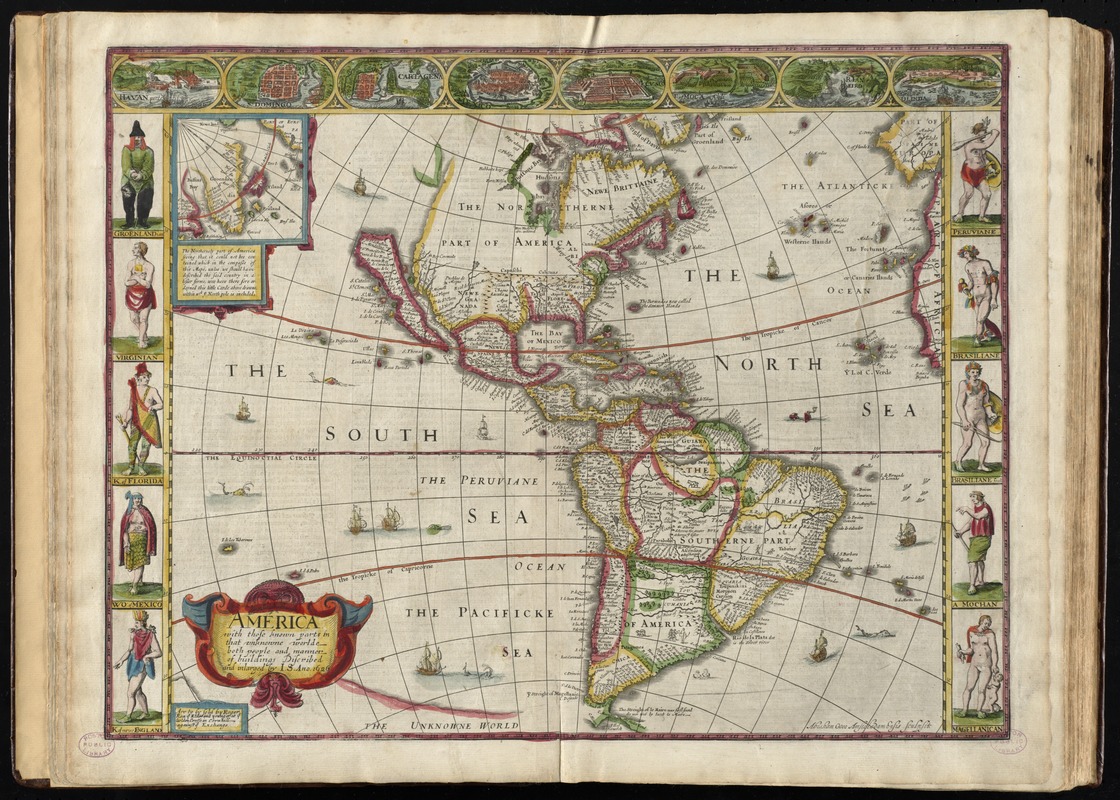

John Speed (1552?-1629)

America: with Those Known Parts in that Unknowne Worlde both People and Manner of Buildings Discribed and Inlarged

London, 1662.

John Speed (1552?-1629)

A New and Accurat Map of the World

London, 1662.

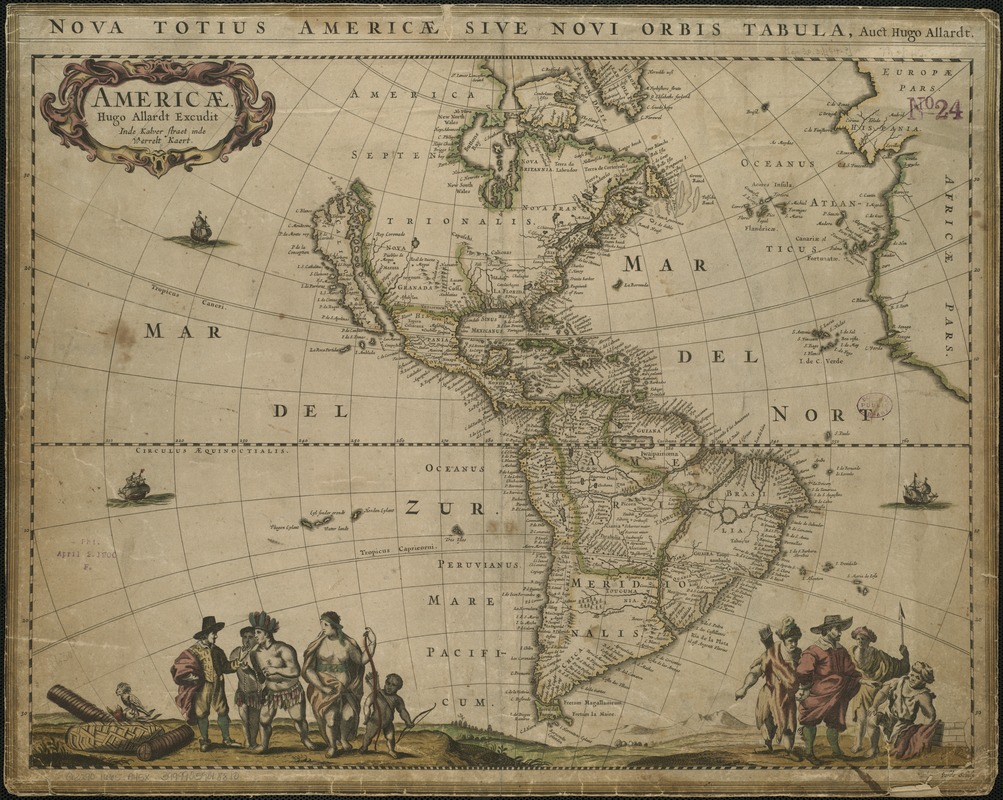

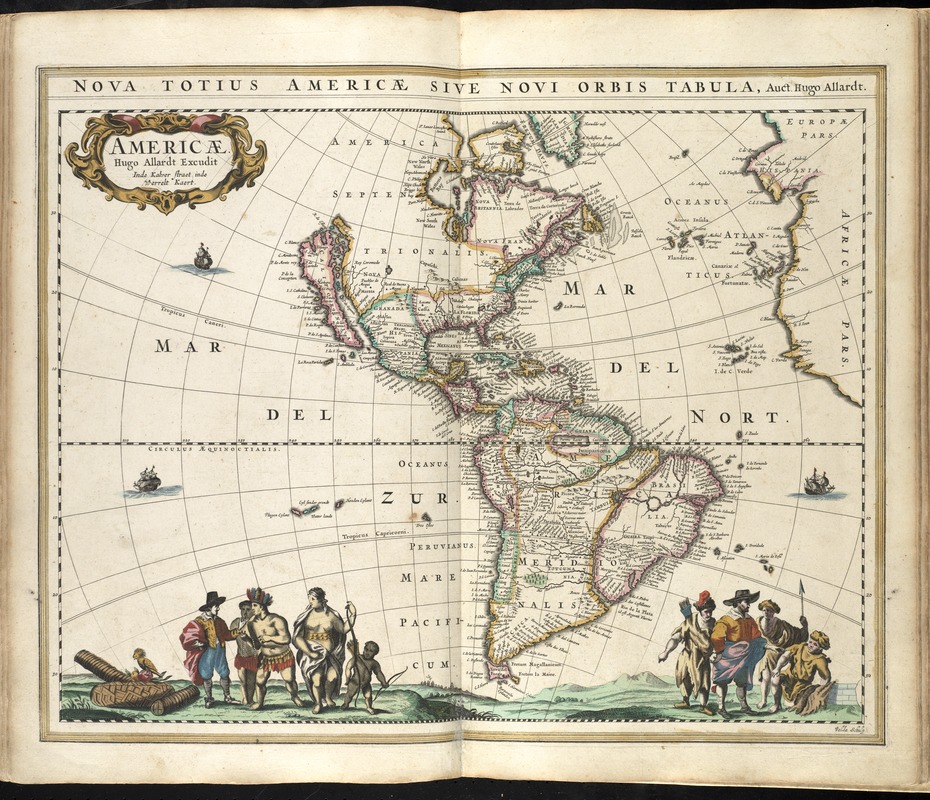

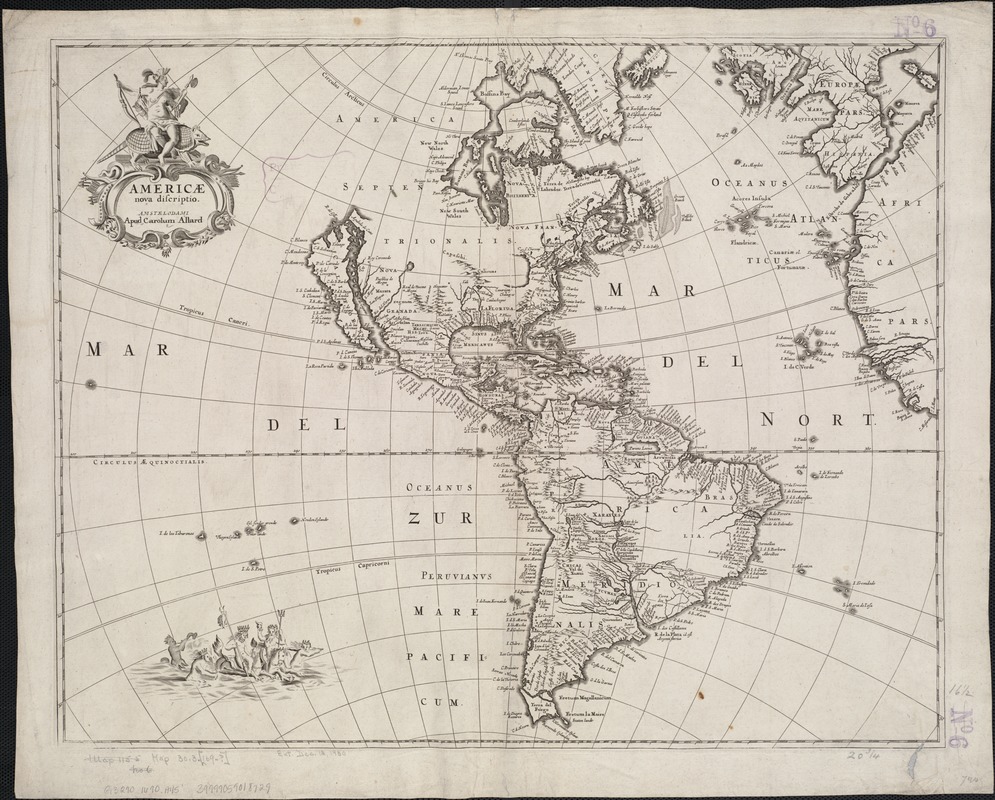

Hugo Allardt (1625-1691)

Americae

Amsterdam, 1665.

Hugo Allardt (1625-1691)

Americae

Amsterdam: Hendrick Doncker, 1665.

Moses Pitt (fl. 1654-1696)

Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Geographica ac Hydrographica Tabula

Oxford, England, 1680.

Nicholaes Visscher (1649-1702)

Novissima et Accuratissima Totius Americae Descriptio

Amsterdam, 1690.

Carel Allard (1648-ca. 1709)

Americae Nova Discriptio

Amsterdam, [1690?]

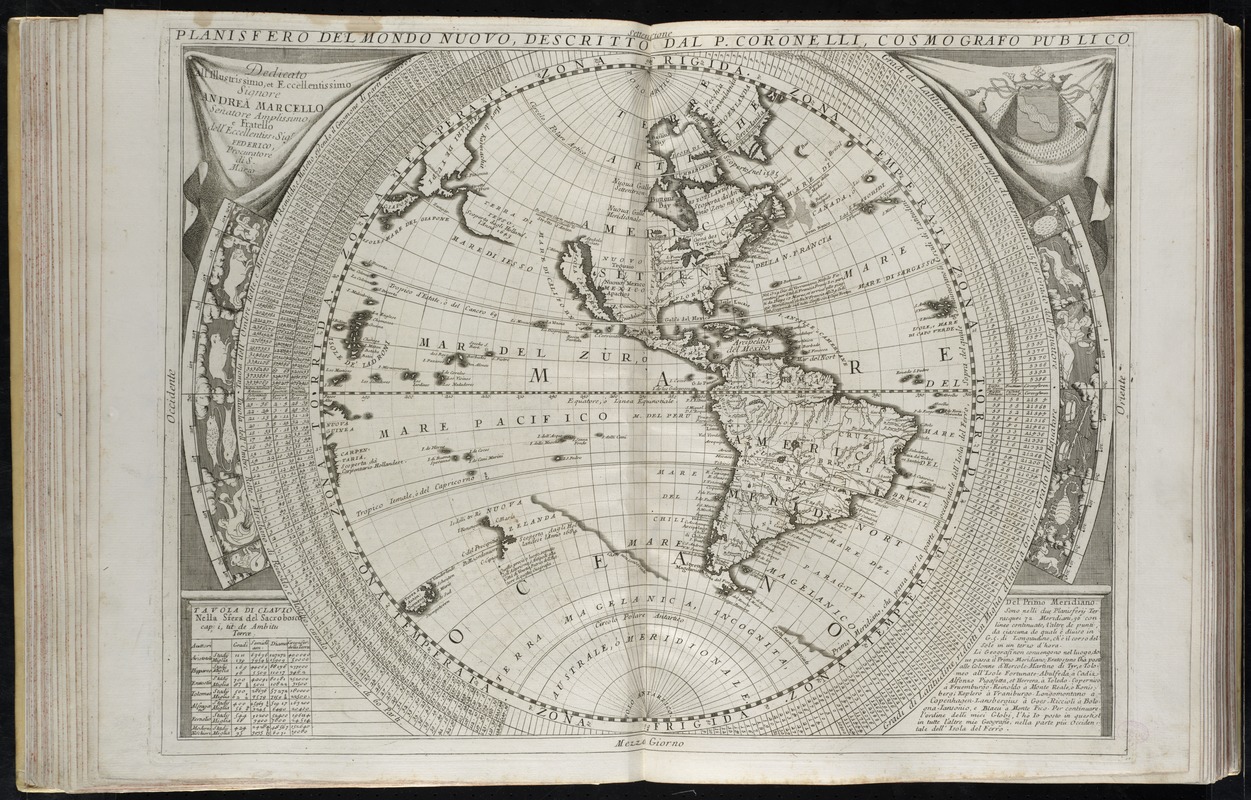

Vincenzo Coronelli (1650-1718)

Planisfero del Mondo Nuovo

Venice, 1691.

3. 18th Century – The Imaginary Isle of O’Brazil

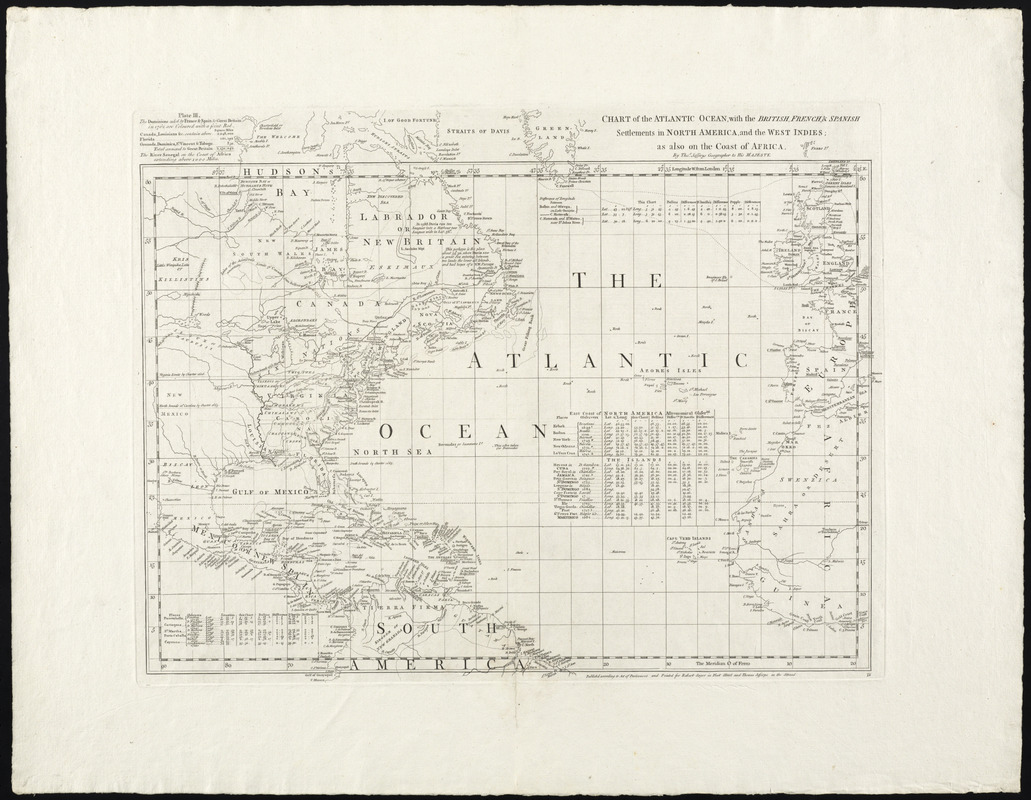

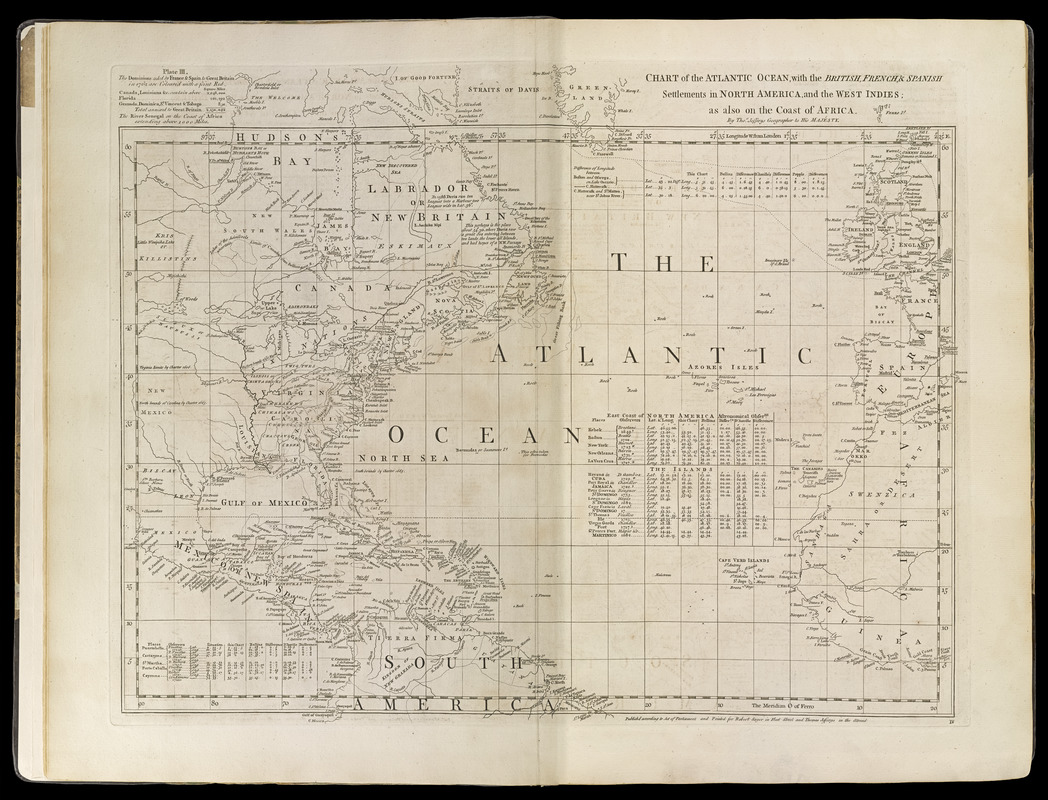

John Green, [né Bradock Mead] (ca. 1685-1757)

Chart of the Atlantic Ocean, with the British, French, & Spanish settlements in North America, and the West Indies: as Also on the Coast of Africa

London, 1753.

Courtesy of the Richard H. Brown Revolutionary War Map Collection.

By the mid-18th century, the former “physical” island of Hy-Brasil had morphed into legend. Irish mapmaker John Green, born Bradock Mead, includes the island on his 1753 chart of the Atlantic Ocean. However, in this case, Green provides the following description near the site “Imaginary Isle of O Brazil.” Green, along with English mapmaker Thomas Jefferys, produced a number of maps during the 1750s and 1760s. These highly detailed maps were based on the latest knowledge gained from expeditions across the Atlantic Ocean, and by the mid to late 19th century, mariners were certain there was no physical island of Hy-Brasil where is had been reported to be for nearly 400 years. Despite this, the island would remain on some maps for the next century.

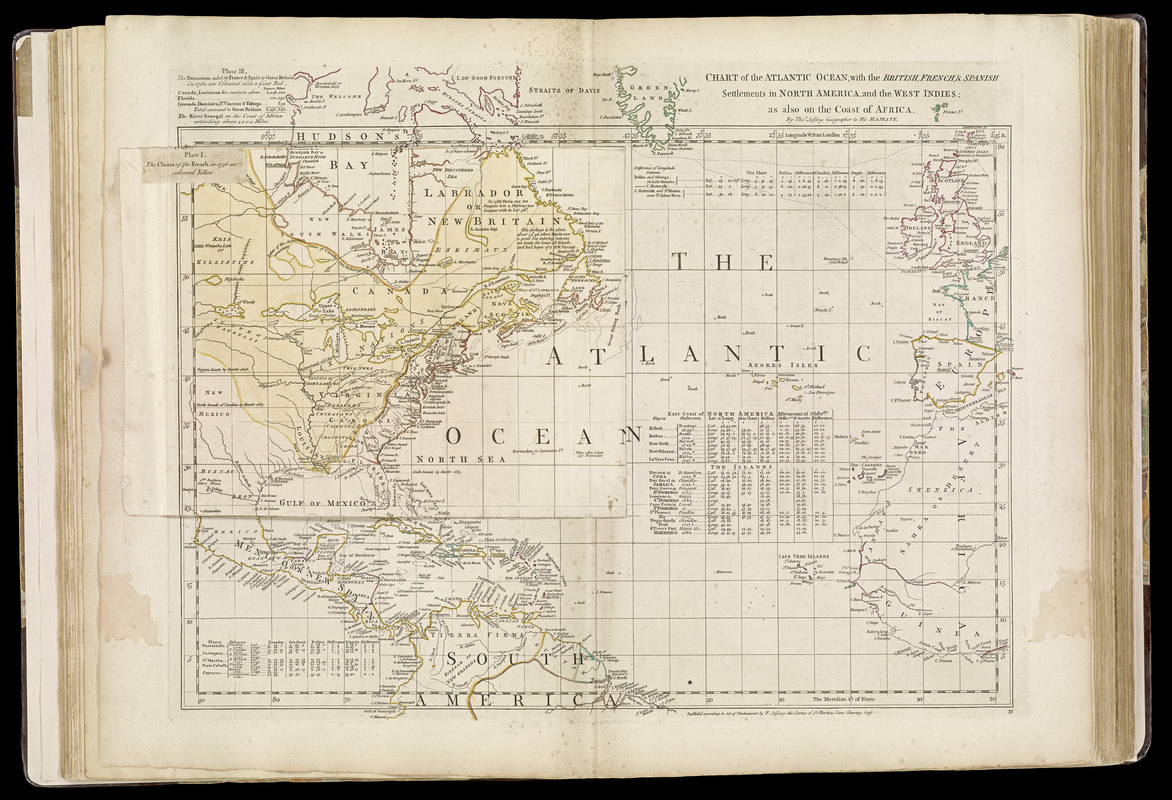

Thomas Jefferys (c. 1710-1771)

Chart of the Atlantic Ocean, with the British, French, & Spanish settlements in North America, and the West Indies

London, [1768]

John Green, [né Bradock Mead] (ca. 1685-1757)

Chart of the Atlantic Ocean, with the British, French, & Spanish Settlements in North America, and the West Indies: as Also on the Coast of Africa

London, 1768.

4. Late 18th century – The Rock of Brasil

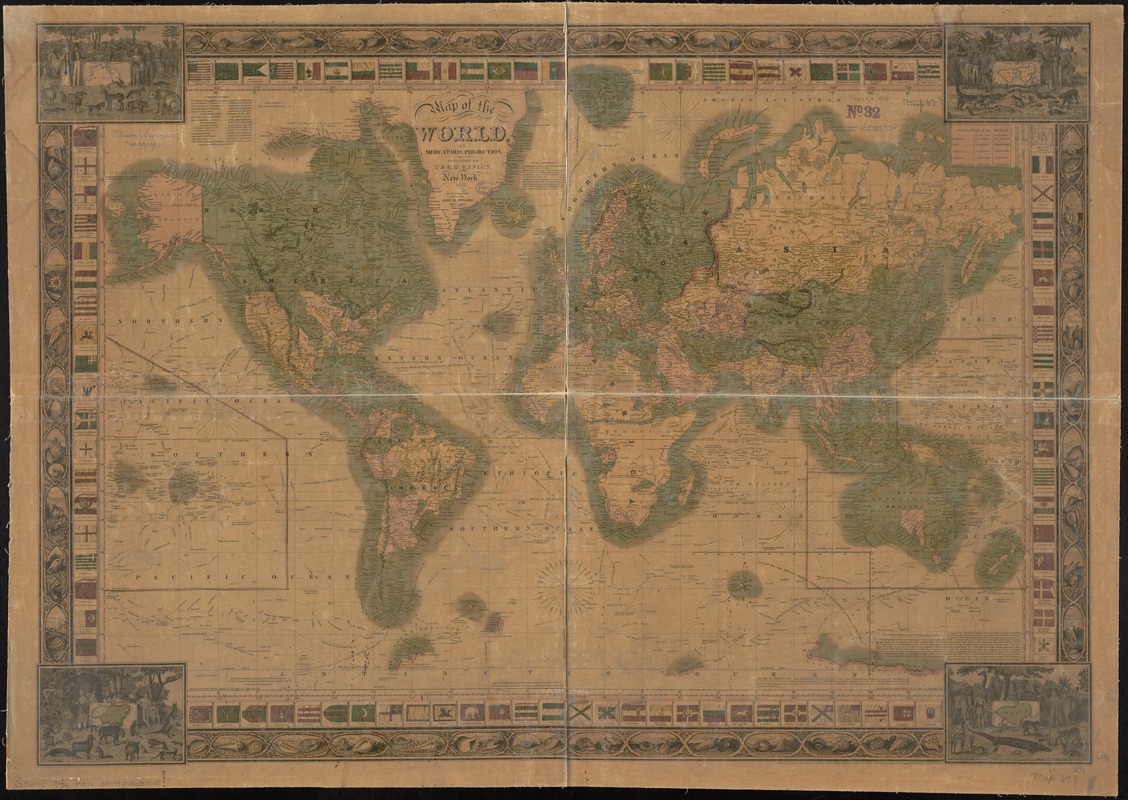

John M. Atwood (fl. 1840-1883)

Map of the World, on Mercator’s Projection

New York, 1846.

By the late 18th century, the name of the elusive island had changed again – this time to the “rock” of Brasil, or “Brazil Rock.” This designation would continue to be used on maps for nearly another century. This 1846 world map produced in New York is the first example of an American-made map that includes Hy-Brasil in this exhibition. All other maps discussed up to this point in the online exhibition have been produced in Europe. In John Atwood’s map displayed here, he labels the island “Basil Rock,” but locates the island in its original position on the southwest coast of Ireland. This map uses the Mercator projection, as did a number of other maps in this exhibition from the 17th and 18th centuries.

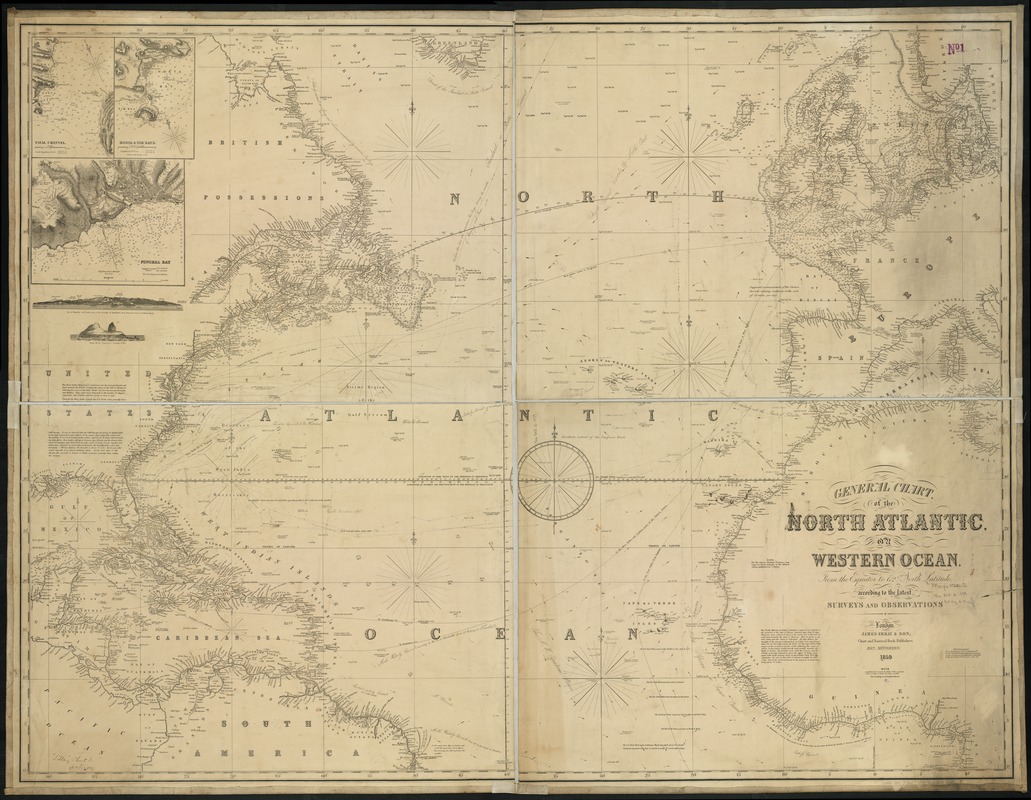

James Imray & Son

General Chart, of the North Atlantic, or Western Ocean, from the Equator to 62° North Latitude, According to the Latest, Surveys and Observations

London, 1859.

James Imray and Son’s 1859 chart of the Atlantic Ocean is the last time we see Hy-Brasil featured on maps in this online exhibition. In this example, filled with thousands of nautical soundings (water depths), the mapmaker lists the once proud Hy-Brasil as “Brasil Rock: high [sic] doubtful.” By the second half of the 19th century, there had been no substantive evidence that any sailor, adventurer or fortunate human had ever truly set foot on Hy-Brasil. Therefore, by 1873, the island was finally removed from British Admiralty navigational charts. The legendary island of Hy-Brasil had managed to remain on maps and charts for over 500 years – a testament to the power of myth, hope and imagination.

Bibliography

Babcock, William H. Legendary Islands of the Atlantic: A Study in Medieval Geography. New York: American Geographical Society, 1922. CALL NO.: G100 .B3

Freitag, Barbara. Hy Brasil: The Metamorphosis of an Island: From Cartographic Error to Celtic Elysium. Textxet Studies in Comparative Literature, vol. 69. New York: Rodopi, 2013.

Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí. “The Mystical Island in Irish Folklore.” In Islanders and Water Dwellers, edited by Patricia Lysaght. Blackrock Co. Dublin: DBA Publications Ltd., [1996]. CALL NO.: GR137.C46 1996x

Johnson, Donald J. Phantom Islands of the Atlantic: The Legends of Seven Lands That Never Were. New York: Avon, 1998. CALL NO.: GR940.J65 1998x

Manguel, Alberto, Gianni Guadalupi. The Dictionary of Imaginary Places. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, c1987. CALL NO.: GR650.M36 1987

Morrison, Samuel E. The European Discovery of America: The Northern Voyages A.D. 500-1600. New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1971. CALL NO.: E101.M85

Post, J.B. An Atlas of Fantasy. Baltimore: The Mirage Press, 1973. CALL NO.: G3122.P6 1973

Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society. (Worcester: Charles Hamilton, 1874), 61: 6-7. Accessed electronically through Internet Archive. <https://archive.org/details/proceedingsamer84socigoog> (19 May 2016).

Ramsay, Raymond H. No Longer on the Map: Discovering Places that Never Were. New York: The Viking Press, c1972. CALL NO.: GN751.R29

Sauer, Carl O. Northern Mists. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1968.

Van Duzer, Chet. Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps. London: The British Library, 2013. CALL NO.: GA781.V36 2013

Westropp, Thomas J. Brasil and the Legendary Islands of the North Atlantic: Their History and Fable: A Contribution to the “Atlantis” Problem. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, vol. 30, sect. C (Dublin: Hodges, Figgis & Co., 1912-13), 223-260. CALL NO.: PER 3300.6

Winsor, Justin, ed. Narrative and Critical History of America. Vol. 1. New York: AMS Press, 1967. CALL NO.: E18.W765 1967

Yeats, W.B., ed. Fairy and Folk Tales of Ireland (Gerrads Cross, Buckinghamshire: Colin Smyth Ltd., 1973). CALL NO.: GR147.Y42 1973

Credits

Curator

Stephanie Cyr

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center Staff

Lauren Chen, Cataloger

Connie Chin, President

Alison Cody, Development Manager

Stephanie Cyr, Assistant Curator of Maps

Ronald Grim, Curator of Maps

Michelle LeBlanc, Director of Education

Evan Thornberry, Reference and

Geospatial Librarian

Catherine Wood, Office Manager

Graphic Design and Production

Framing and Matting

Andrew Leonard

Contributors to the Exhibition

Caoimhghin Ó Fraithile

Special Thanks

Kathleen Bitetti, Medicine Wheel Productions

Press

This Imaginary Island Appeared in Maps for 500 Years

Popular Mechanics, September 24, 2016

How an Imaginary Island Stayed on Maps for Five Centuries

Hyperallergic, September 20, 2016

Leventhal Map Center at BPL spotlights Mythical Irish Island

Boston Irish Reporter, August 17, 2016