Introduction

Boston and Beyond: A Bird’s Eye View of New England celebrates the Boston Public Library’s remarkable collection of bird’s eye views. These views represent a unique genre of cartographic materials that were drawn as if the artist viewed a town from an elevated or bird’s eye view perspective. They were compiled and published primarily in North America during the last half of the 19th century and the early decades of the 20th century.

The collection consists of approximately 500 such views. The exhibit displays a selection of approximately 50 views of New England towns and cities focusing on Boston, its suburbs, and a variety of communities in both coastal and interior settings extending from Cape Cod to the Connecticut River. Most of these images were drawn and published by artists in the Boston area, including Howard H. and Oakes H. Bailey, Edwin Whitefield, Albert F. Poole, and George W. Walker.

While 17th- and 18th-century European cartographers depicted many important cities from an elevated aerial perspective, the 19th-century North American genre is very distinctive. It proved to be a much more democratic medium, documenting large cities, towns and small villages in equal style and grandeur.

By comparing these views with late 19th-century topographic maps, it is evident that the artists often displayed a perspective and bias in selecting a particular (non-north) orientation. A few surviving field sketch notes and manuscript drawings reveal that the artists did not actually view their subjects from an elevated perspective, but walked the streets sketching individual buildings. Then they prepared a composite drawing depicting the town to its best promotional advantage.

Themes

The Changing Urban Landscape

Cities and towns change and grow just like everything else . During the last half of the 19th century, Boston was in a period of major change, growing both horizontally (expanding its shoreline and borders) and vertically (raising its skyline).

By comparing the Boston views chronologically, it is possible to document the outward expansion of Boston’s original Shawmut Peninsula as the Back Bay was filled-in and eventually settled.The contrast is clear between Freeman Richardson’s 1864 landscape view in which the Back Bay reclamation has not yet begun and Oakley Bailey’s 1879 map in which it is complete and new real estate developments are rapidly taking hold.

As Boston’s population outgrew its original physical location, the city also expanded beyond the peninsula into the neighboring townships.Eventually, the City of Boston annexed such communities as East Boston, Roxbury, Dorchester, Jamaica Plain, and Hyde Park.

Boston’s fast-growing population was the result of an active, growing economy and, just as its borders were expanding out, its skyline was also expanding up. In Albert Poole’s 1905 map of Boston, we see the 19th century’s three and four-story buildings replaced by high rise commercial and office buildings.

As shown in these illuminating maps, Boston’s landscape was changing outward and upward – the natural result of its place at the center of New England commerce and culture.

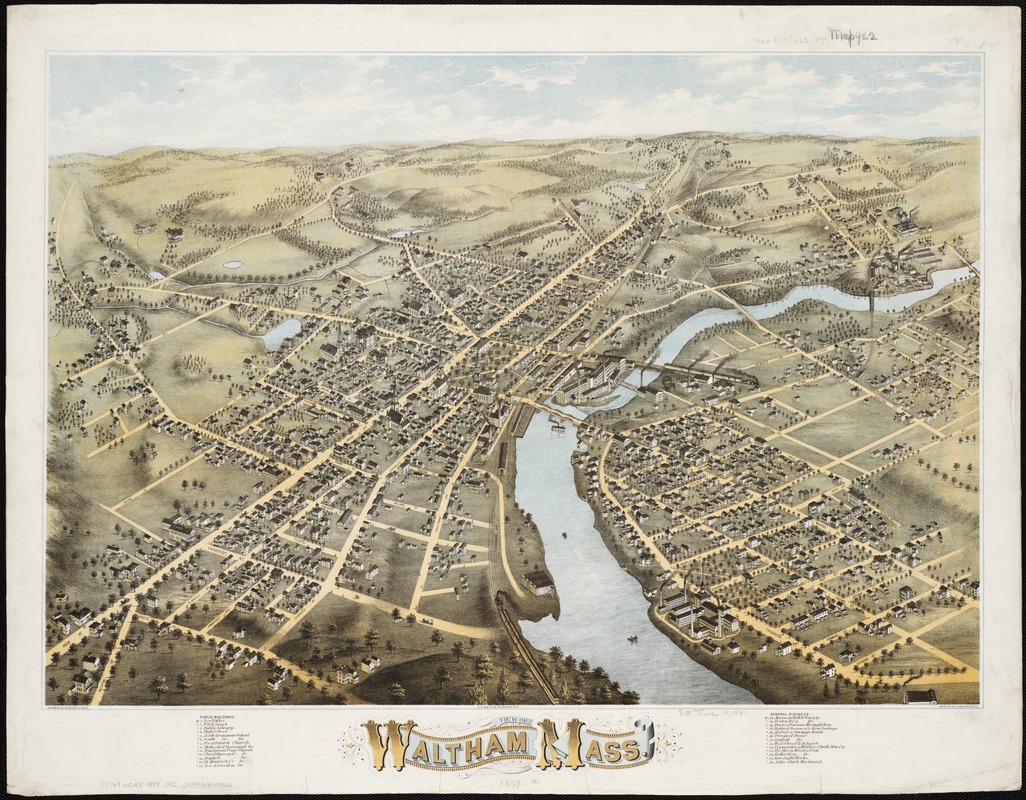

Water Power and Smoke Stacks

With the introduction of the Industrial Revolution into New England in the late 18th century and the early 19th century, the region’s economy changed dramatically. Formerly agricultural towns like Waltham, shown in the 1877 view, became industrial centers. Initially small factories were constructed to take advantage of water power sites on New England’s many fast flowing rivers and streams. By the last half of the 19th century when the bird’s eye views were created, these original industrial sites became large industrial complexes utilizing steam power.

Fulfilling their role as agents of boosterism, the bird’s eye view artists emphasized the fast-growing urban functions of their subject cities and towns. In the Waltham view, we see that the focal point is the Boston Manufacturing Company at the heart of a large industrial complex on the Charles River.

Sails, Ships and the Summer Crowd

New England’s coastal towns, many of which date back to the first European settlements in the 17th century, have long looked to the sea for their economic livelihood. Shipping, ship building, whaling and fishing prospered well into the middle of the 19th century. However, as steamships overtook the swift clipper ships and petroleum products replaced whale oil, these communities adapted to changing circumstances. A few, such as Gloucester, continued to prosper as fishing communities. Others, especially those on Cape Cod and the Islands, retained their maritime focus but became summer resorts, offering a relaxing haven for artists and the wealthy. Finally, some including Plymouth, New Bedford, and Providence turned to industry, building factories on the small tributary streams feeding in to the harbor or utilizing steam power.

All Aboard! Connection Towns by Rail

With the adaptation of the steam engine to transportation, trains and their associated iron rails became a major component of southeastern New England’s transportation network during the 19th century. Railroads supplemented already existing roads, turnpikes, and canals, but quickly grew to be the most expeditious means of moving manufactures goods and people over long distances, connecting the inland manufacturing town with each other and Boston, the region’s commercial hub. They proved to be an essential ingredient in New England’s urban and industrial growth in the last half of the 19th century. The prominence of railroad stations in many of the bird’s eye views illustrates both the importance of this transformative transportation technology.

Howard Bailey’s 1875 view of Nashua, New Hampshire, actually shows a railroad station that had yet-to-be built and placed it very prominently in his drawing. In the 1883 depiction of the same city, Bailey’s brother, Oakley, presented the station as it was actually constructed but with much less emphasis, positioning it in the lower right corner.

The State House Dome, Court House Cupolas, and Church Spires

Public buildings, such as the Massachusetts State House, county court houses, city halls, churches and schools, as well as public spaces, including town commons and parks, appear in almost every bird’s eye view. However, in some bird’s eye views, the artists displayed these buildings more prominently.

For example, Fuch’s 1870 view of Boston, which commemorates a July4th celebration, places the Commons, Public Garden, and State House in the center foreground The 1881 view of Malden, published the same year it was incorporated as city, identifies City Hall as number 1 in the legend and places it in the center of the image. In some views, such as the 1877 view of Waltham, the churches appear to be drawn out of proportion to the other buildings,, or in towns, such as Dedham and Barnstable, that serve seats of county government, the county court houses and jails appear in the center of the drawing.

1. Beyond but Before

Although bird’s eye views of North American cities and towns published during the last half of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th century are considered a unique cartographic genre, there was a precedent for their creation in the history of mapping and imaging cities.

With the advent of the printing press, European cartographers could employ different perspectives to depict their cities. Some of these views included:

- The landscape view -- viewing the town at ground-level;

- The bird’s eye view -- viewing the town from an oblique angle 2,000 -3,000 feet above the ground;

- The traditional map or street plan -- viewing the town directly overhead or from a position perpendicular to the ground.

Some of the earliest books, especially travel narratives published during the 16th century, included urban views and maps, but the first comprehensive collection of town plans and views was published in 1572 by the German cleric Georg Braun and engraved by Franz Hogenberg. Braun and Hogenberg continued to collect and publish town plans and views, illustrating approximately 500 towns from a variety of perspectives.

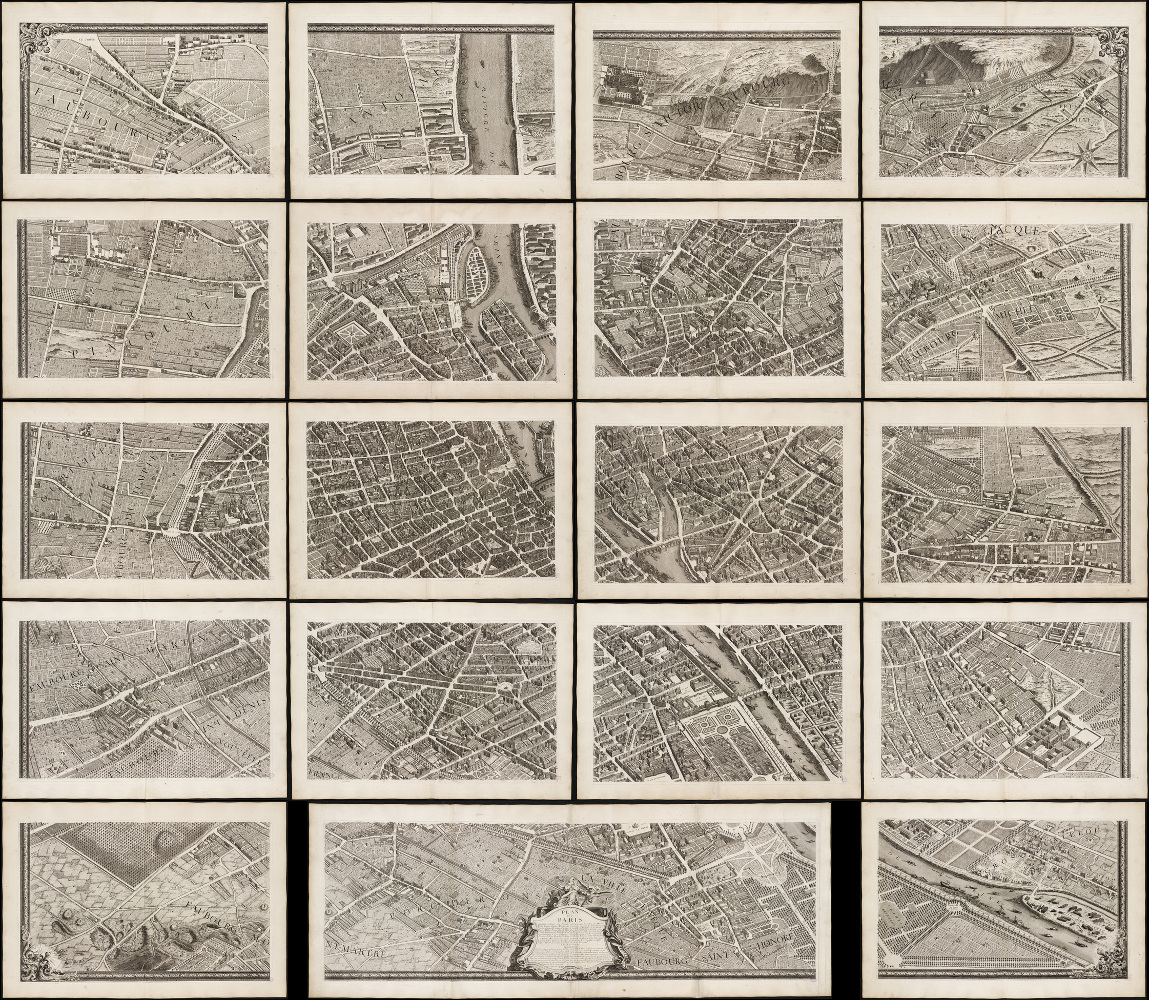

A distinct 18th-century variation of urban mapping was large multi-sheet wall maps of large and important European cities. Cities mapped in this manner included London, Dublin, Rome, Vienna, Prague, and Paris. Some of these, like the one of Paris displayed here, were drawn from a bird’s-eye perspective.

Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg - 1617

“Hierosoyma urbs sancta Judeae . . .”

In Civitates Orbis Terrarum (Cologne)

Jerusalem, a city sacred to three of the world’s major religions, was depicted as four different images in Braun and Hogenberg’s comprehensive collection of town views. The second volume offers a detailed and realistic-appearing bird’s eye view of the city. In this image, the city is viewed as if the artist was standing on the Mount of Olives looking west.

Muslim control of Jerusalem at this time is represented by the figures in oriental costume in the foreground and the buildings with domes and minarets topped with crescents.

This view records a Christian pilgrimage to the Holy City and, while unsigned, appears to be based on a 1546 drawing by Venetian artist Domenico dalle Greche, while on pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

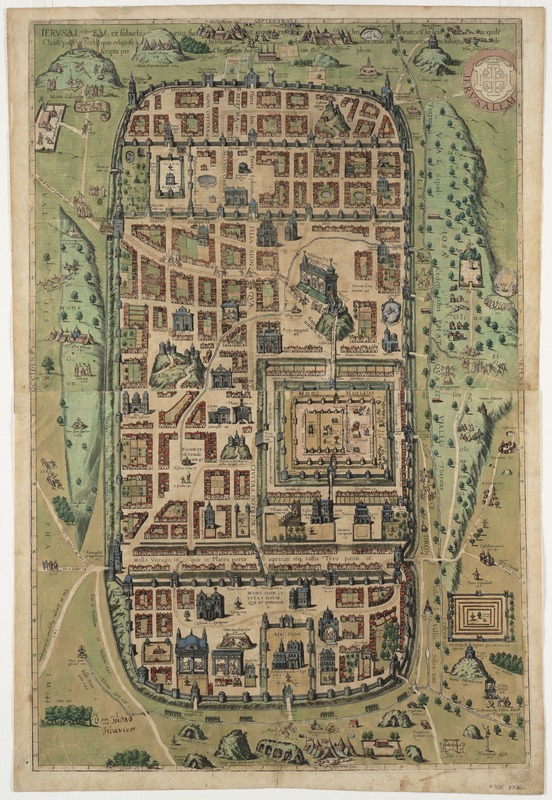

Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg - 1617

“Jerusalem, et suburbia eius . . .”

From Civitates Orbis Terrarum (Cologne)

This final image of Jerusalem in Civitates Orbis Terrarum is the most dramatic. Rather than a bird’s eye view, this depiction is more of a pictorial map, showing the facades of buildings placed adjacent to the streets and not drawn in perspective.

As the extended title indicates, the map was compiled by Christiaan van Adrichem, a Dutch theologian and cartographer, to depict Jerusalem at the time of Christ. The original map was oriented with west at top. In the Civitates, the map was rotated to a vertical format, placing north at the top.

The map presents an imaginary conception of the city, with many buildings depicted as 16th century European structures. In addition there are 270 numbered and captioned scenes, showing events mentioned in the Bible and other historical sources.

Gérard Jollain (d. 1683)

Nowel Amsterdam in L’ Amerique

[Paris], 1672

One of the earliest European attempts to publish a view of a North American city from a bird’s eye perspective is this image titled New Amsterdam. Issued in 1672 by French publisher, Gérard Jollain, it was deliberately mislabeled. Eight years earlier, the British had captured the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam and renamed it New York.

Not only is the map outdated, it is also completely fictitious! In fact, the street pattern, the buildings, and the hilly topography are those of late 16th-century Lisbon, Portugal.

As if he was trying to prove the view’s geographical accuracy, Jollain added an inset showing the relative location of New Amsterdam within the New Holland colony. He also added place names showing the adjacent British colony of Massachusetts and neighboring Indian groups.

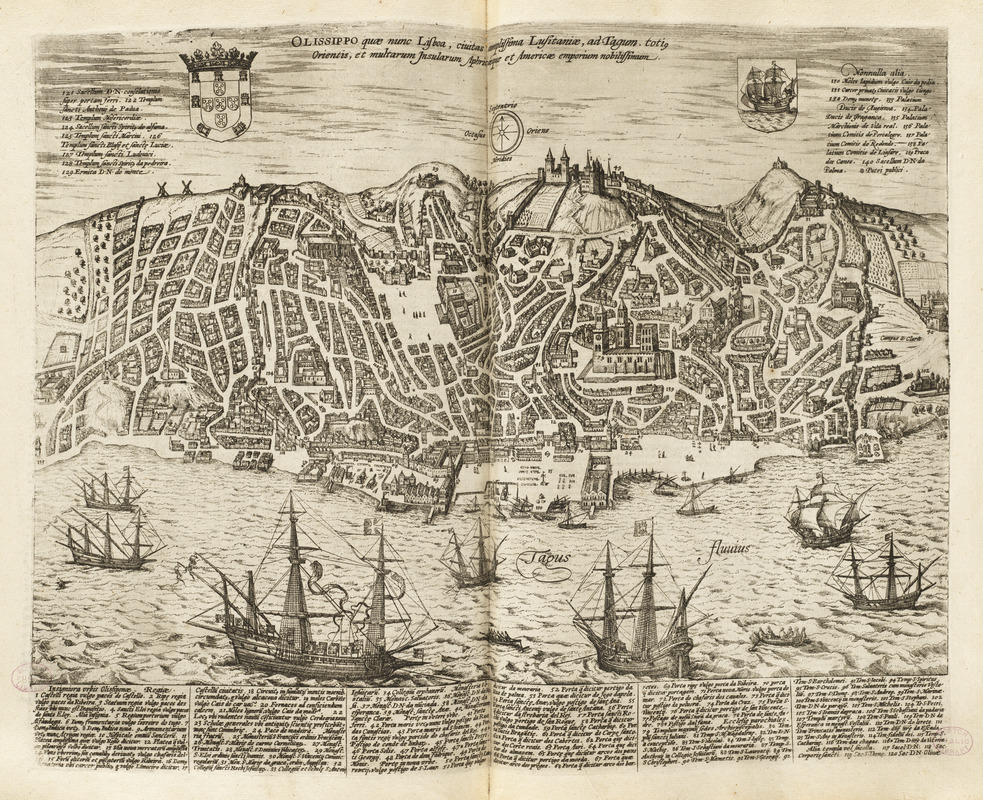

Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg - 1617

“Olissippo, quae nunc Lisboa . . .”

In Civitates Orbis Terrarum (Cologne)

Jollain’s representation of New Amsterdam was based on this image of Lisbon, originally published about 1598 in part five of Braun and Hogenberg’s comprehensive collection of urban views, Civitates Orbis Terrarum. So popular was this view that it was repeatedly republished in other atlases during the 17th century.

This view portrays Lisbon at the height of its prosperity during the European Age of Discovery and Exploration. Clearly evident are the medieval street pattern shaped by a hilly terrain, the castle and cathedral dominating the city’s skyline, and a busy port filled with ocean-going vessels.

Louis Bretez (d. 1738)

Plan de Paris, commencé de l’année 1734

[Paris, 1739]

In marked contrast to the small, single-page city views appearing in late 16th and 17th century town atlases, were large, multi-sheet wall maps and bird’s eye views published during the 18th century. These richly detailed urban images depicted Europe’s largest and most important cities. Displayed here is one page from a 20-sheet view of Paris, drawn from a bird’s eye perspective.

This large scale drawing of Paris was prepared by Louis Bretez, a sculptor, painter, and specialist in perspective drawings. It took Bretez five years to complete this work. Here the city is viewed from the northwest, looking southeast, with the Seine River running through the middle of the composition. Bretez also places Île de la Cité and Île St. Louis, the historic heart of the city, near the center of the image.

2. Boston

As New England’s largest city and commercial hub, Boston was documented in more urban views than any other New England community. Nine of these, dating from 1850 to 1905, are displayed here. They view the city from different elevations and different perspectives or orientations.

Several are landscape views, but most depict the city from a bird’s eye perspective. The views are from all around the peninsula – northwest, northeast, east, southeast, southwest, and west. Consequently, each view emphasizes a different aspect of the city’s geography – public spaces (State House, Commons, and Public Garden), transportation facilities (harbor wharves and warehouses, railroad stations), and central business district (commercial and financial buildings).

This chronological sequence also documents the city’s changing geography during the last half of the 19th century. These views provide evidence of the city’s physical growth as various land fill projects were completed, such as infilling between wharves and land reclamation in the Back Bay and South Cove areas.

The tension between ship and rail is evident, as the city’s significance as a railroad center outdistanced its maritime activities. Simultaneously the city’s changing skyline, initially marked by the State House, the Bunker Hill Monument, churches, and three or four-story commercial buildings, became increasingly dominated by ten to twelve-story commercial buildings, highlighting the city’s emerging importance as a financial and commercial hub.

John Bachmann (fl. 1849-1885)

Bird’s Eye View of Boston

New York, 1850

John Bachmann, a German immigrant, was one of the earliest and finest producers of urban bird’s eye views. During his career, he published two views of Boston – one in 1850 and the other in 1877.

In this early version, Bachmann viewed the city from the southwest, looking directly at the Public Garden and the Common, with the remainder of the downtown greatly diminished by perspective. While various railroads appear along the edges of this image, the bustling harbor, filled with many ships, occupies the upper center portion of the drawing.

Such a perspective highlights the city’s pride in its most prominent public spaces, but it also underscores the importance of shipping to the city’s economy during the first half of the 19th century.

John Bachmann (fl. 1849-1885)

Boston, Bird’s-Eye View from the North

Boston, 1877

This later Bachmann view depicts the city from the northwest side of the peninsula, placing the State House, the Common, the Public Garden, and the newly reclaimed and developing Back Bay in the center of the drawing.

Beacon Hill, the West End, and the Bullfinch Triangle with various railroad lines feeding into North Station appear in the foreground of the image.

With smoke belching from trains approaching and leaving the North End stations, this view highlights the importance of rail traffic to the city’s growth during the last half of the 19th century. The docks and ships illustrated in the foreground attest to the former importance of maritime trade and activity to the city’s economic growth.

Gift from Bank of America

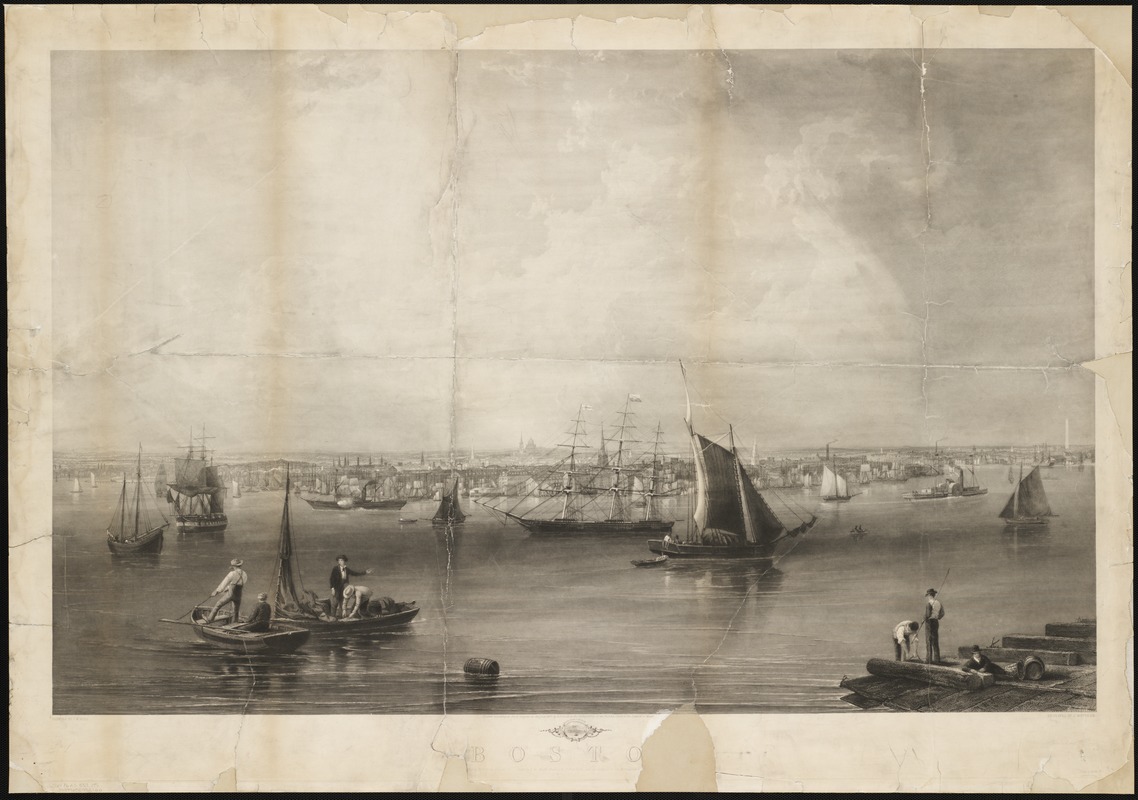

John W. Hill (1812-1897)

Boston [proof sheet]

New York and Boston, 1857

This romantic view of the city of Boston was painted by the accomplished artist John W. Hill. In composing his rendition, Hill employed a traditional ground-level or landscape perspective. He places the waterfront and the cityscape in the bottom two fifths of the drawing while filling the upper three fifths with the dramatic setting of a cloud-filled sky.

Hill portrays the city from the northeast as if standing across the harbor in East Boston. His drawing emphasizes the city’s waterfront and wharves, with a number of ships and workmen dominating the foreground. The city’s prominent buildings are depicted most accurately with the State House providing the central focal point. Church steeples, smoke stacks, and the Bunker Hill Monument poignantly pierce the skyline.

As indicated in the lower left margin, this was a “proof” sheet and is uncolored.

Freeman Richardson (fl. 1860s)

Environs of Boston, from Corey Hill, Brookline, Mass.

Boston, 1864

Richardson’s 1864 landscape view of Boston’s environs provides another example of a ground-level or low-elevation urban view published during the 1850s and 1860s when bird’s eyes views were just beginning to gain in popularity. Published in 1864 at the end of the Civil War, this pastoral landscape belies the notion that Boston was an active participant in a turbulent and destructive war that the Union barely survived.

In this presentation, Boston is viewed from the southwest. Using Corey Hill in Brookline as his vantage point, the artist placed Brookline’s semi-rural landscape in the foreground, with the yet unfilled Back Bay and city proper fading into the horizon. While Brookline appears to be a residential community, Boston proper is more densely settled, with smoke stacks, church steeples, and commercial buildings punctuating the skyline.

Gift from Bank of America

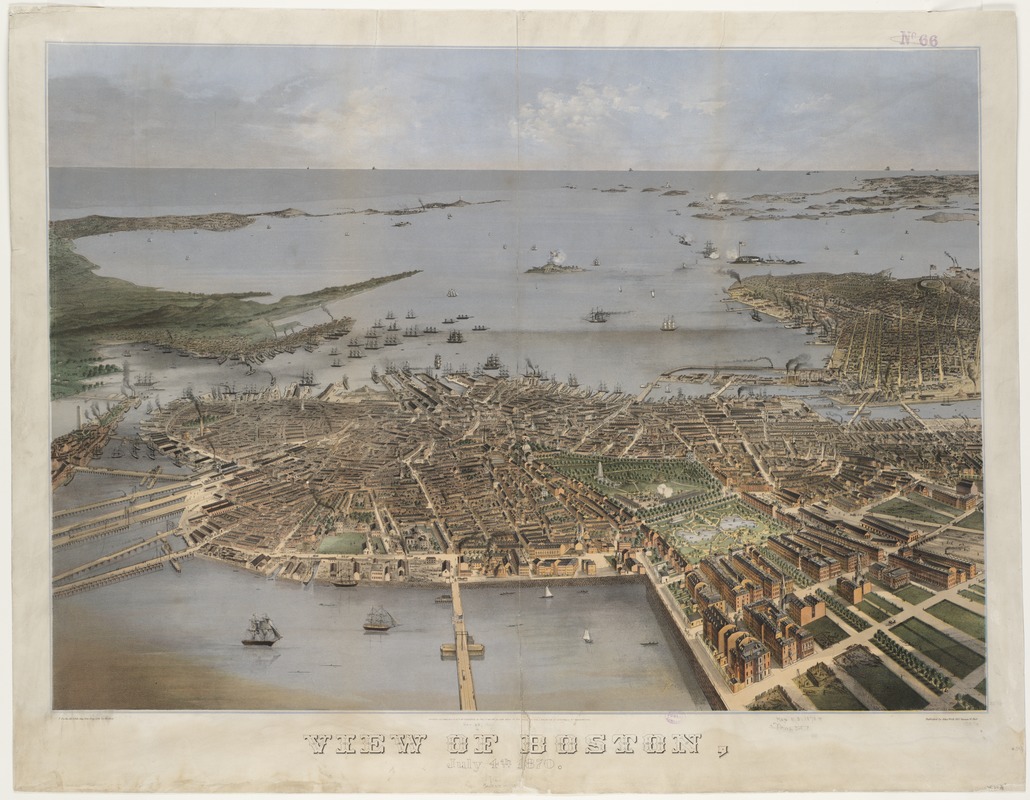

F. Fuchs

View of Boston, July 4th 1870

Philadelphia, 1870

This view of Victorian Boston portrays a prosperous city during its 1870 Independence Day celebration. The artist created this view looking at the city from the west.

In the Boston Common a military re-enactment is taking place. Boston Harbor and Bay occupy the upper half of the composition, with cannons firing and American flags flying proudly over the forts on Governor and Castle Islands.

The artist shows a city undergoing rapid change. Industries are beginning to crowd portions of the waterfront. Although the harbor is full of the clipper ships that brought fame to Boston in the 1850s, the placement of the railroad facilities in the foreground of the image confirms the success of this popular new mode of transportation.

[Charles R. Parsons]

Bird’s-eye View of Boston, Showing the Burned District

From Harper’s Weekly (New York), November 30, 1872

Most bird’s eye views were not designed to depict a specific date. However, this view is tied to an actual event, similar to Fuchs’ view dated July 4, 1870. Three weeks after Boston’s great fire of November 9 and 10, 1872, Harper’s Weekly published this view illustrating the extent of the burned district.

In this journalistic presentation, the city is viewed from the east with the burned district highlighted by shading. The designated area includes that portion of today’s Financial District bordered roughly by Summer, Washington, Milk, and Broad Streets. The fire engulfed more than 60 acres of some of the most valuable real estate in the city, destroying 930 businesses valued at approximately $100,000,000 (about $3.5 to $4 billion in current dollars).

Gift of Bank of America

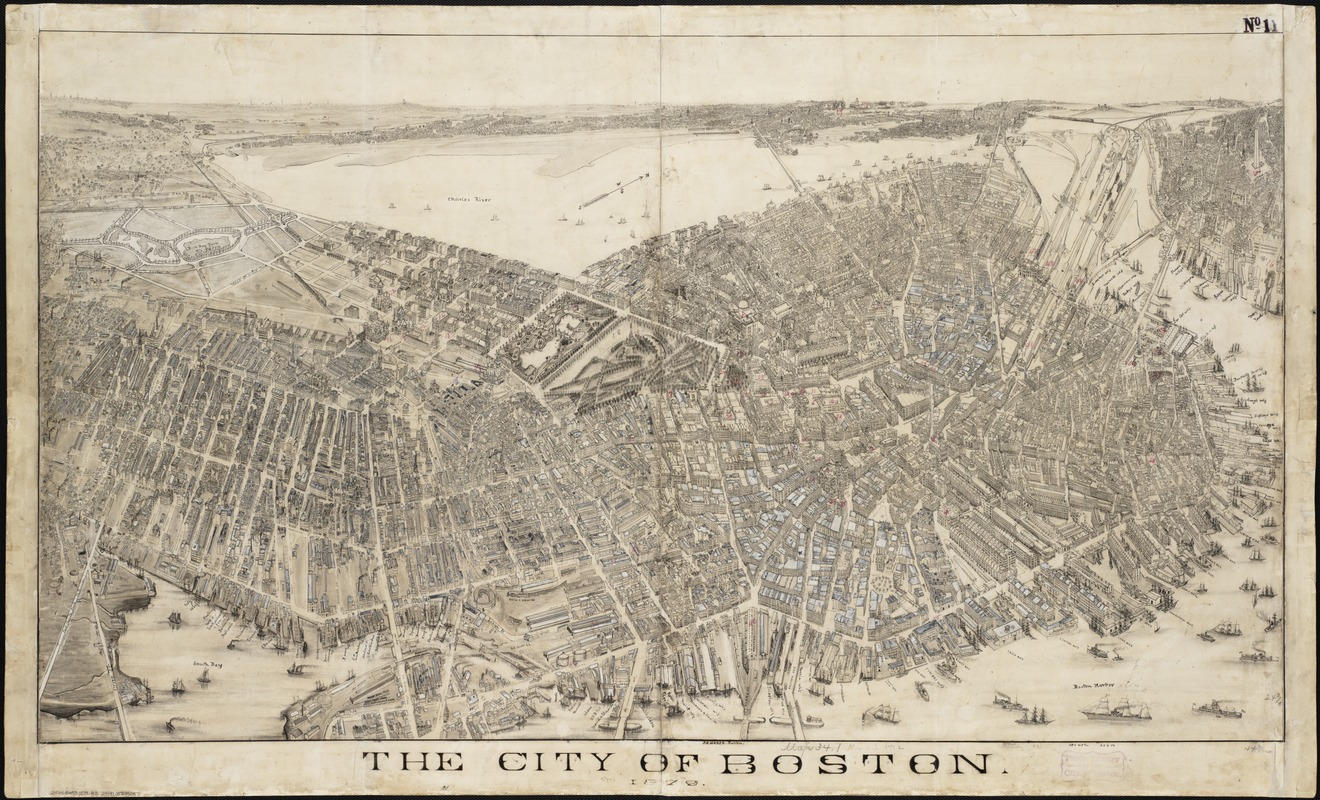

Charles R. Parsons (1821-1910) and Lyman W. Atwater (1835-1891)

The City of Boston

New York, 1873

Published by the New York firm of Currier and Ives, this dramatic and colorful bird’s eye view depicts the city from the northeast. It places the eastern waterfront with numerous ships, wharves, and warehouses in the foreground. As was the custom with Currier and Ives urban views, the buildings in the immediate foreground and center portions are shown in the greatest detail, while the upper half of the drawing is generalized and buildings are only suggested as the city fades into the background.

One assumes that this image is a portrayal of the city as it existed in 1873, the year of its publication. However, it does not show any of the destruction resulting from the November 1872 fire. Parsons’ sketches of the city, from which the lithograph was derived, were apparently recorded before the fire.

Oakley H. Bailey (1843-1947) and James C. Hazen (1852-1908)

The City of Boston [lithograph]

Boston, 1879

This is the largest and most detailed bird’s eye view of Boston proper. It depicts the city from the southeast as if the artist is positioned above South Boston. Consequently, he places the rail lines terminating in the vicinity of present-day South Station and the busy eastern waterfront in the foreground, with the central business district dominating the central portion of the drawing.

By 1879, the burned district had been rebuilt and Back Bay had been completely reclaimed, although this new real estate was only partially developed. Almost all the buildings within the city are shown in fine, realistic detail.

The legend in the bottom margin identifies 59 important buildings and localities, highlighting the political, commercial, transportation, religious and cultural activities in the city.

[Oakley H. Bailey (1843-1947)] and James C. Hazen (1852-1908)

The City of Boston [manuscript, pen and ink, with white highlights]

Boston, 1879

This manuscript version of the 1879 Boston view was most likely the final finished drawing used in preparing the lithographic stone for this image. Very few examples of such manuscript drawings have survived.

In comparing the two images, it is apparent that the printed version provided a faithful, although not exact, replication of the manuscript drawing.

The creation of the published version of this view is attributed to O. H. Bailey and J.C. Hazen. Bailey, who moved to Boston in 1874, was one of the most prolific view makers, publishing at least 374 views during a career that spanned fifty-six years. However, the manuscript version is attributed only to Hazen. He was associated with O.H. Bailey in preparing approximately thirty bird’s eye views from 1877 through 1880.

Albert F. Poole (1853-1934)

Twentieth Century Boston

Boston, 1905

This is one of the last recorded bird’s eye views of Boston proper. It foreshadows the vertical growth of downtown during the 20th century, when the late 19th-century skyline composed of buildings no higher than six stories, was replaced with a skyline dominated by high-rise commercial and office buildings.

This image looks at the city from the east as if approaching through Boston Harbor. In the foreground the harbor is filled with a variety of ships, most of which are now steam powered vessels. The central focus of the drawing is the central business district where the skyline is starting to change, with many buildings approaching or exceeding ten stories.

This drawing was created by Bert Poole, a native of Brockton who was also employed as a commercial and newspaper artist.

3. Annexed Suburbs

In addition to the dramatic and stunning depictions of Boston Proper, many bird’s eye views were also prepared for Boston’s suburban neighbors. These images document the suburbanization stimulated by a growing network of street car lines and annexation during the last half of the 19th century.

Many of these neighboring communities, now part of the larger Boston metropolitan region, were established as separate townships during the 17th century. They developed as small agricultural villages during the 18th century, while their neighbor Boston, whose growth was confined to the original Shawmut Peninsula, became the primary port for the Massachusetts colony. As Boston’s growth expanded beyond the peninsula through the various landfill projects, these independent towns were engulfed in Boston’s suburban expansion.

East Boston, Roxbury, Jamaica Plain, Mattapan and Hyde Park were annexed by Boston. Although part of the incorporated City of Boston, they still represent identifiable neighborhoods, but often without discreet boundaries. Brookline, Cambridge, Arlington, Malden, Newton, Watertown, Waltham, Quincy, and Dedham remained independent towns. All are located within Boston’s primary circumferential beltway (Route 128) and are an integral part of Boston’s urbanized area.

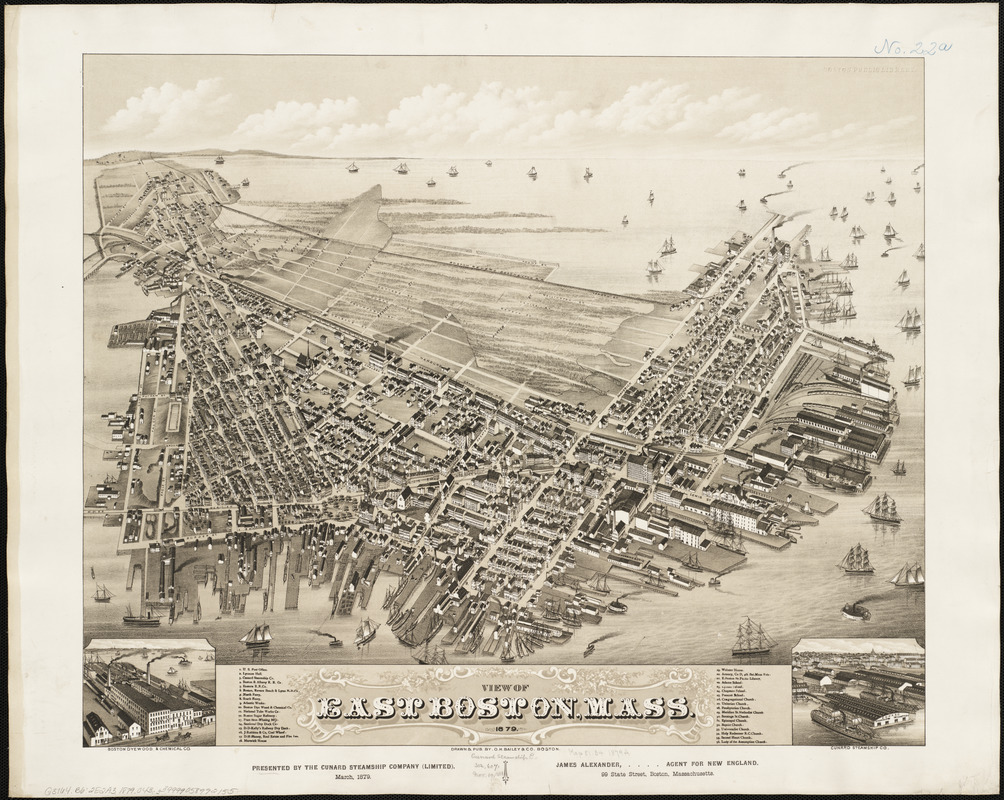

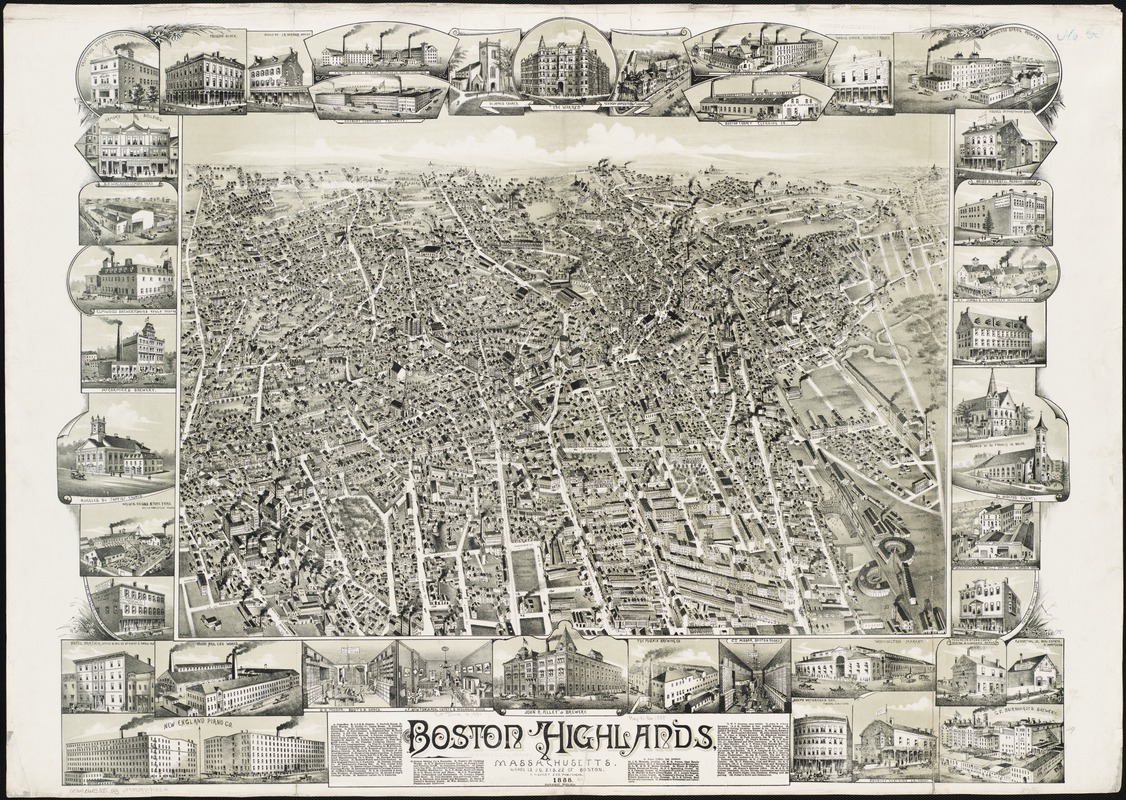

Oakley H. Bailey (1843-1947)

View of East Boston, Mass.

Boston, 1879

Bailey composed this view as if he was positioned above Boston’s North End and Charlestown looking east across the harbor at East Boston. He prominently places the community’s waterfront, docks, and shipyards in the foreground, emphasizing East Boston’s reliance on maritime activities.

In 1844, Donald McKay, who would become America’s leading designer and builder of clipper ships, established his shipyard in East Boston. In this 1879 view, McKay’s waterfront location in the lower left corner of the drawing has been replaced by the Boston Dyewood and Chemical Company.As though symbolic of the clipper ships’ decline this view includes two inset illustrations in opposing corners – on the left, the Dyewood Company, with the hull of an incomplete ship at the adjacent dock, and on the right, the Cunard Steamship Company.

Oakley H. Bailey (1843-1947)

Boston Highlands, Massachusetts, Wards 19, 20, 21 & 22 of Boston

Boston, 1888

This view of Boston looks towards the southwest, as if the artist is positioned above Washington and Shawmut Streets at the base of the original peninsula. Entitled Boston Highlands, it encompasses much of Roxbury, looking out toward Grove Hall, Franklin Park and Jamaica Plain.

During the first half of the19th century Roxbury was developing into a suburban community, and was annexed as part of Boston in 1868. As depicted here, Roxbury exemplifies the classical late-19th-century streetcar suburb. An unsegregated mixture of various types of residential structures, churches, schools, commercial buildings, factories, and railroad facilities dominate the foreground and central portions of the drawing.

The legend and 40 marginal illustrations provide a virtual business directory for the community. The Boston Baseball Grounds appear in the lower right hand corner adjacent to the railroad round houses.

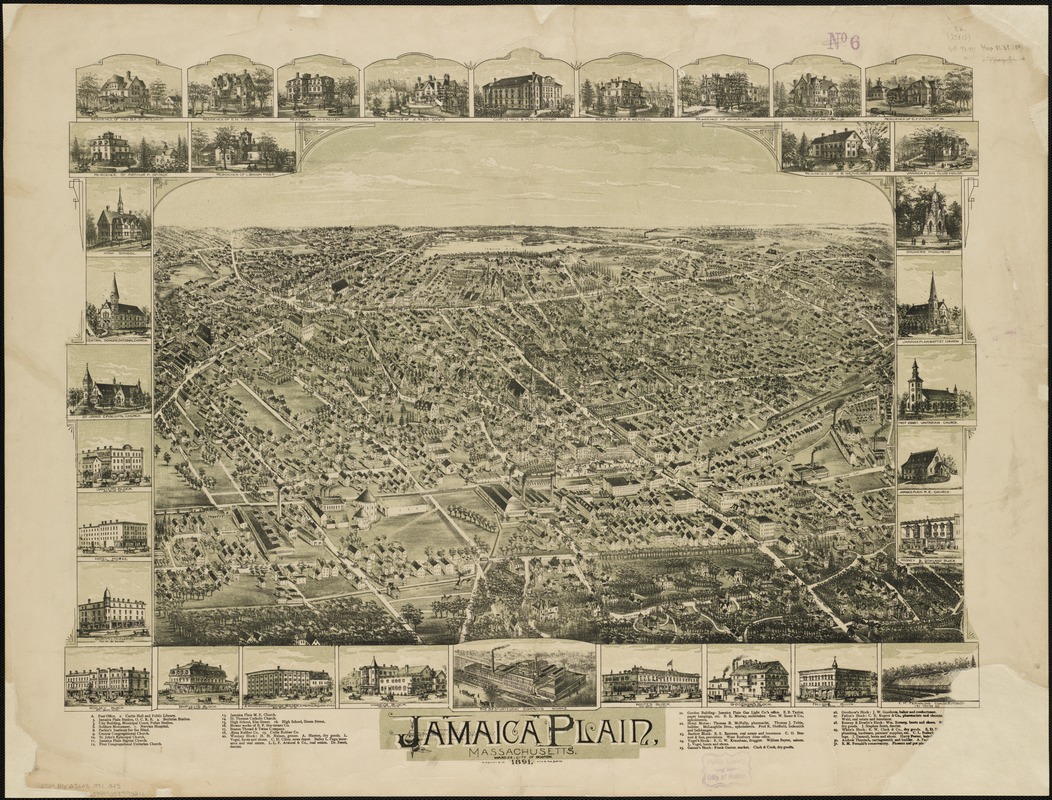

Oakley H. Bailey (1843-1947)

Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts, Ward 23, City of Boston

Boston, 1891

Jamaica Plain is located in the northern part of the town of West Roxbury, which was annexed by Boston in 1874. During the early 19th century, Jamaica Plain was known as a summer resort for wealthy Bostonians but later developed into a street car suburb and an industrial community in its own right.

Viewed from the southeast looking northwestward with Jamaica Pond and Brookline on the horizon, this image emphasizes the village’s industrial base. The B.F. Sturtevant Company, a manufacturer of fans and blowers, was placed both in the drawing’s center foreground and as an illustration in the bottom center of the view. Three other factories, which produced rubber goods, thread, and twine, also appear in the foreground because they are near the railroad tracks that are featured in the lower portion of the drawing.

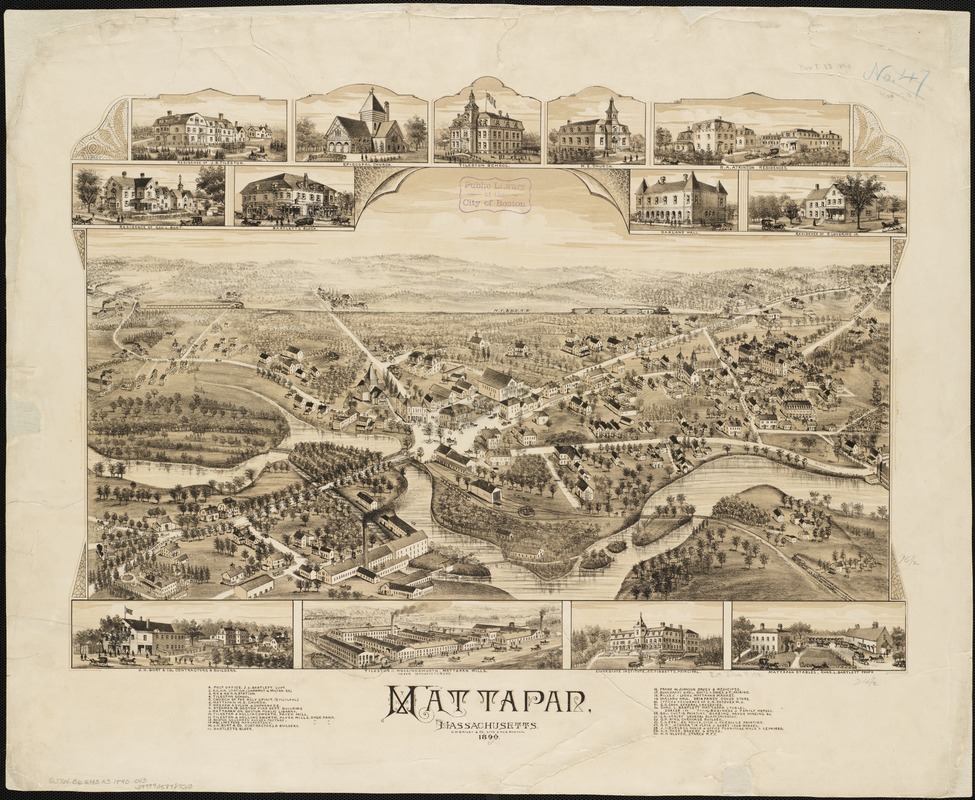

Oakley H. Bailey (1843-1947)

Mattapan, Massachusetts

Boston, 1890

Mattapan, a smaller village located on the Neponset River directly east of Hyde Park, is depicted in this view.

When Mattapan was annexed by Boston the two neighboring communities were separated politically; however, they appear to have been connected economically. Separate plants of the Tileston and Hollingsworth Paper Mill were located in each village, and an inset drawing of the factories is included in each image.

But look closely! The factory depicted in the Mattapan inset is not the same factory that appears directly above in the view. Rather, it repeats the image appearing on the Hyde Park print! Considering that the residence of J.B. Tileston was also placed as the first marginal inset of the Mattapan view, it would appear that the paper company was a major sponsor of both drawings.

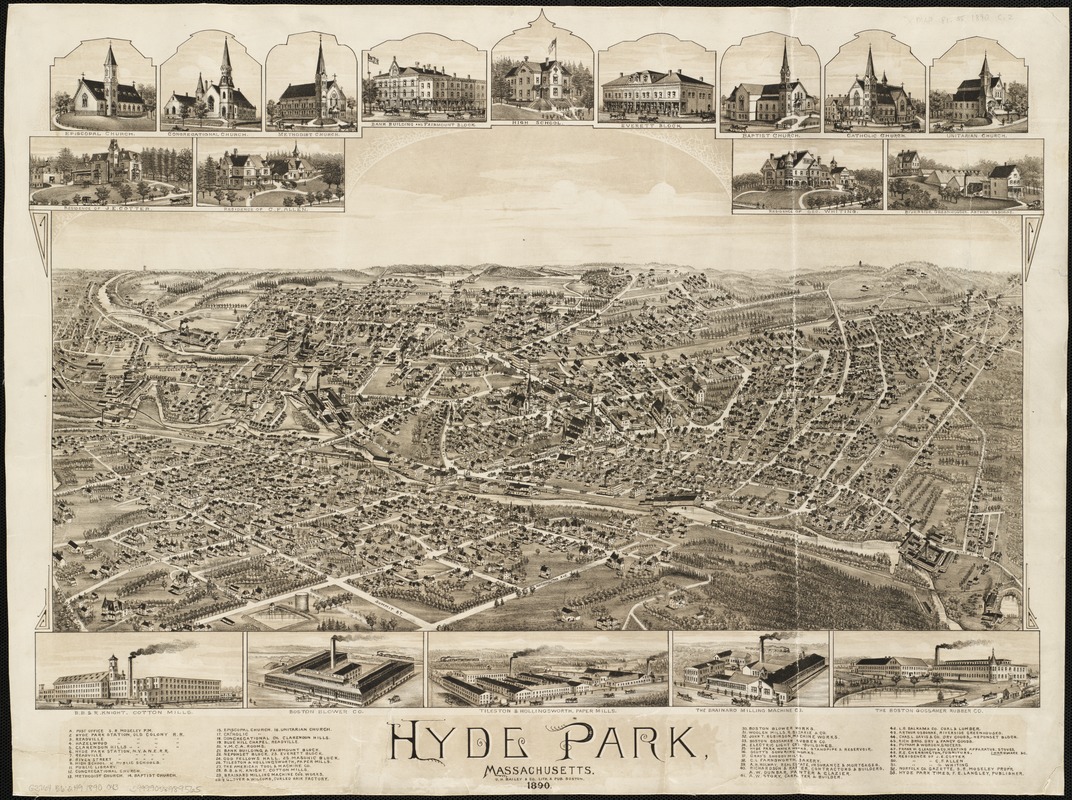

Oakley H. Bailey (1843-1947)

Hyde Park, Massachusetts

Boston, 1890

Located on the Neponset River, defining Boston’s southeastern boundary, Hyde Park developed into a street car suburb of Boston during the last half of the 19th century. In this drawing, the village is viewed from the east.

Besides being a residential suburb, Hyde Park had its own industrial base, with ten large factories identified in the legend and marginal insets. All of these are located near the river and its tributary, Mother Brook, which runs diagonally through the middle of the picture. Proximity to water power was doubtless an important consideration in determining the original location of these factories. Two railroad lines running through the village provide access to the industrial sites.

The town of Hyde Park was incorporated as a township in 1868 and was annexed by Boston in 1912.

4. Adjacent Suburbs

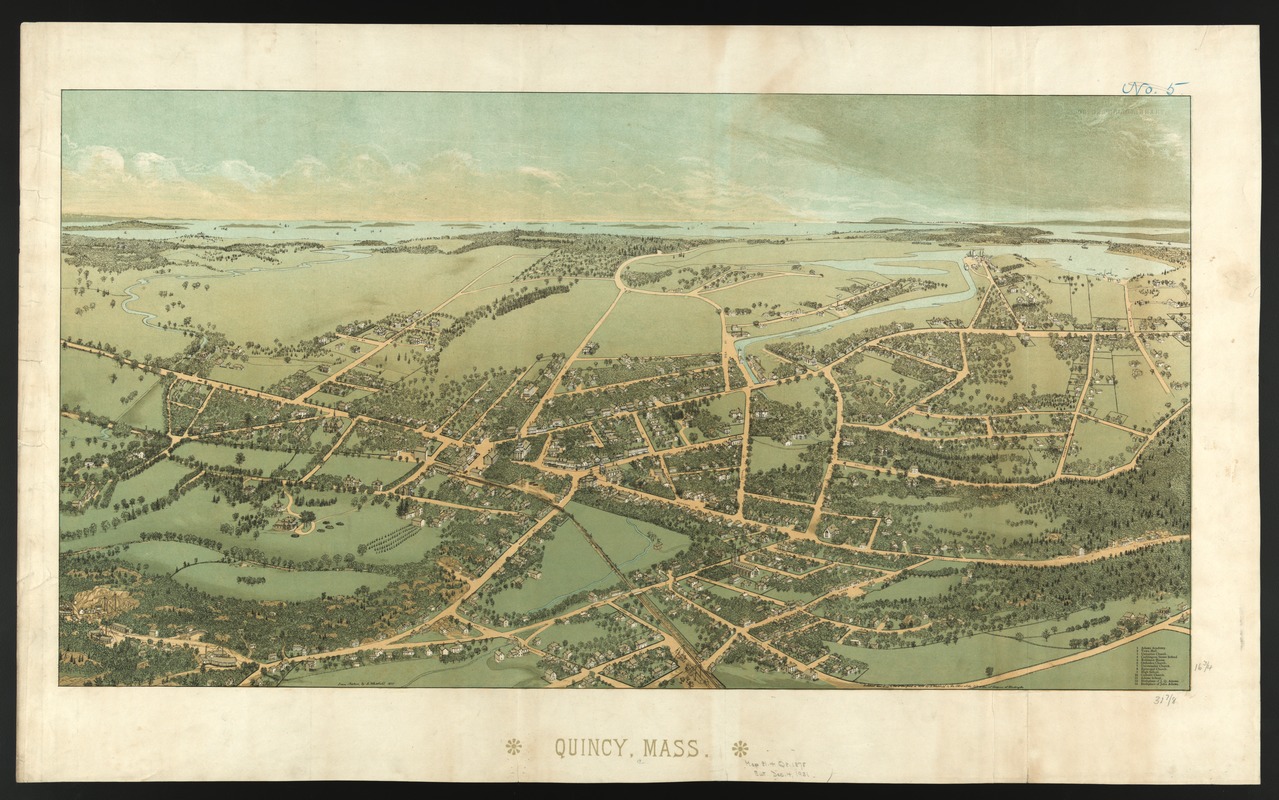

Edwin Whitefield (1816-1892)

Quincy, Mass.

[Boston], 1878

One year after Whitefield completed the Dedham view, he published this bird’s eye view of Quincy, a nearby town also in Norfolk County.

Like Dedham, Quincy was depicted as a quiet, country village. Whitefield chose to identify Quincy’s town hall, five churches, four schools, and the birthplaces of John and John Quincy Adams (numbers 12 and 13). The granite quarries, for which Quincy was noted, are visible in the lower left corner at the end of Granite and Quarry Streets, while docks and shipyards appear in the upper right hand corner.

In composing this presentation, Whitefield viewed the town from the south looking slightly northeast toward Boston Bay. In addition, he drew the railroad running through the center of the drawing.

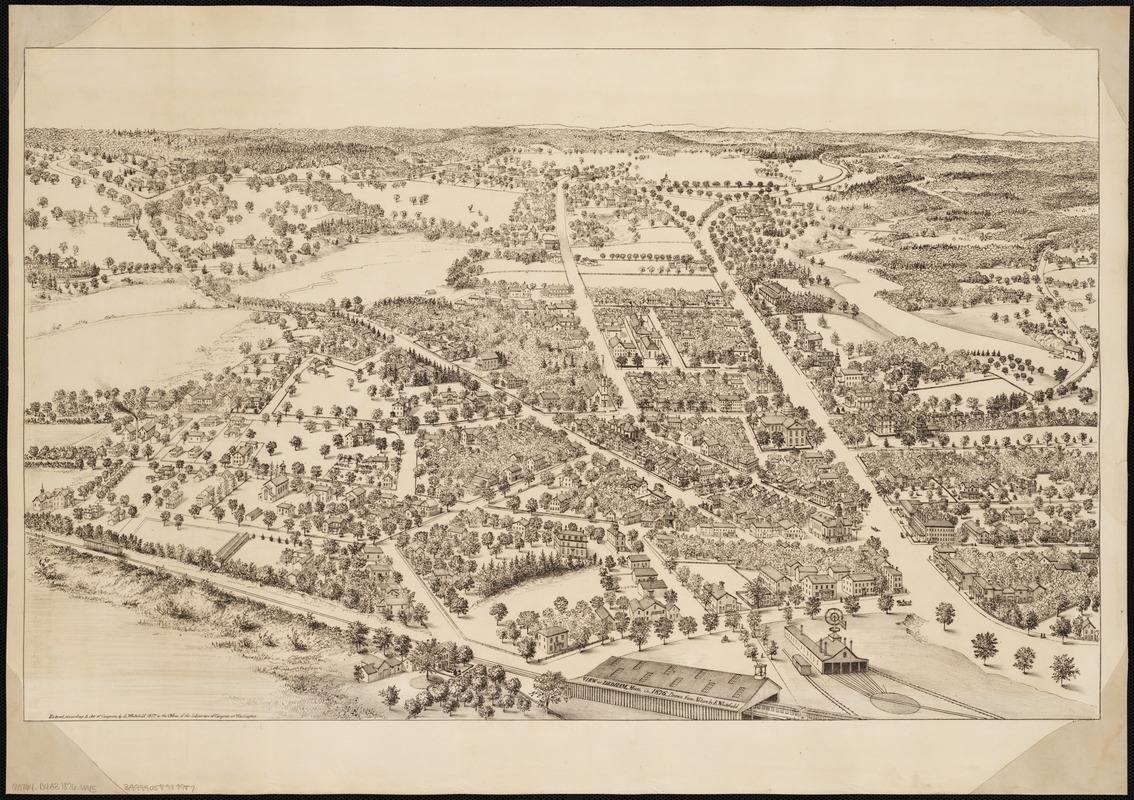

Edwin Whitefield (1816-1892)

View of Dedham, Mass. in 1876, Drawn from Nature

[Boston], 1877

Whitefield was well known as an artist of urban views during the middle of the 19th century. Between 1845 and 1878 he produced fifty-nine lithographic views of cities and towns throughout the northeastern United States and eastern Canada.

In comparison to bird’s eye views produced by other artists, Whitefield’s appear stark and spare. There is little sense of boosterism. None of the buildings appear exaggerated or drawn out of proportion to the other buildings and the unlabeled streets are minimally populated.

What is pictured is a quiet country village, which was a fairly accurate portrayal. Dedham, founded in 1635 as one of the colony’s first inland towns, became the county seat of Norfolk County in 1793. Although a center of transportation, it was not noted for its heavy industry.

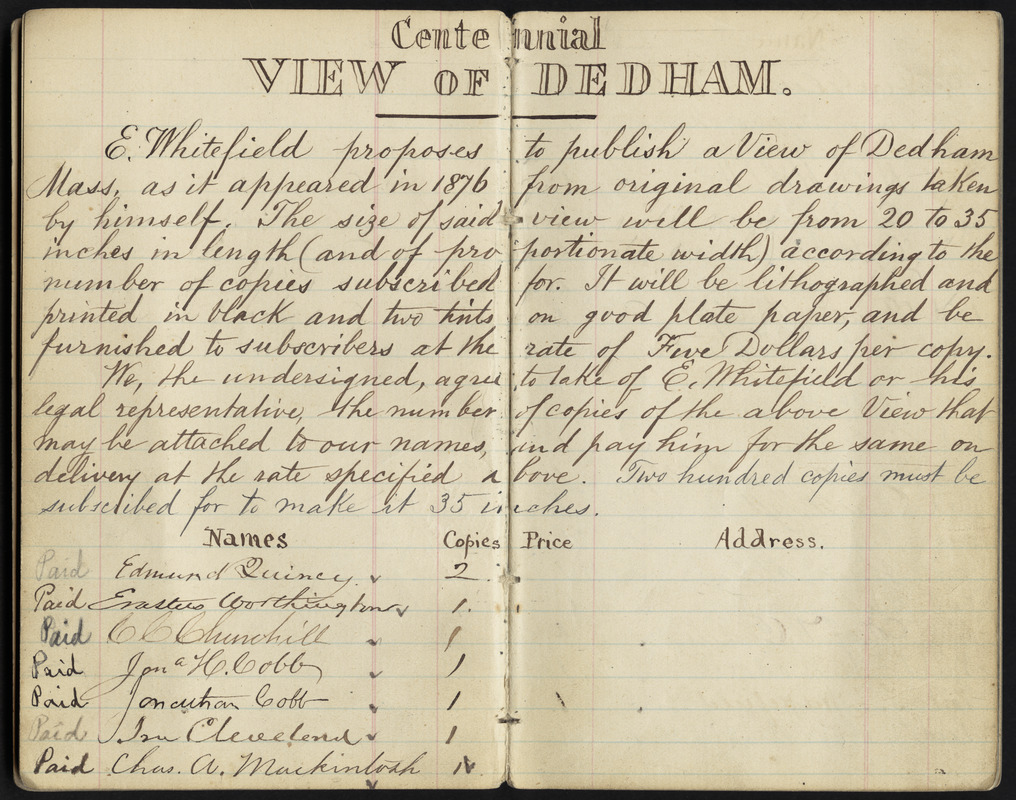

Edwin Whitefield (1816-1892)

“[Subscription list for] Centennial View of Dedham,” in manuscript notebook entitled Dedham, ink and pencil on paper, ca. 1876

Boston Public Library, Print Department, Whitefield Collection

In a small notebook labeled “Dedham,” Whitefield maintained the subscription list for his bird’s eye view of the central village. In his introductory comments, he stated his intention of publishing a “centennial” view of Dedham as it appeared in 1876.

He indicated that it would be compiled from original drawings that he recorded. He also proposed that the published view would measure from 20 to 35 inches, reaching the latter dimension only if he was able to obtain 200 subscriptions at $5.00 per copy. Apparently, Whitefield did not meet his goal since only about 100 subscribers agreed to purchase the view and the lithographic view measures 28 inches in length.

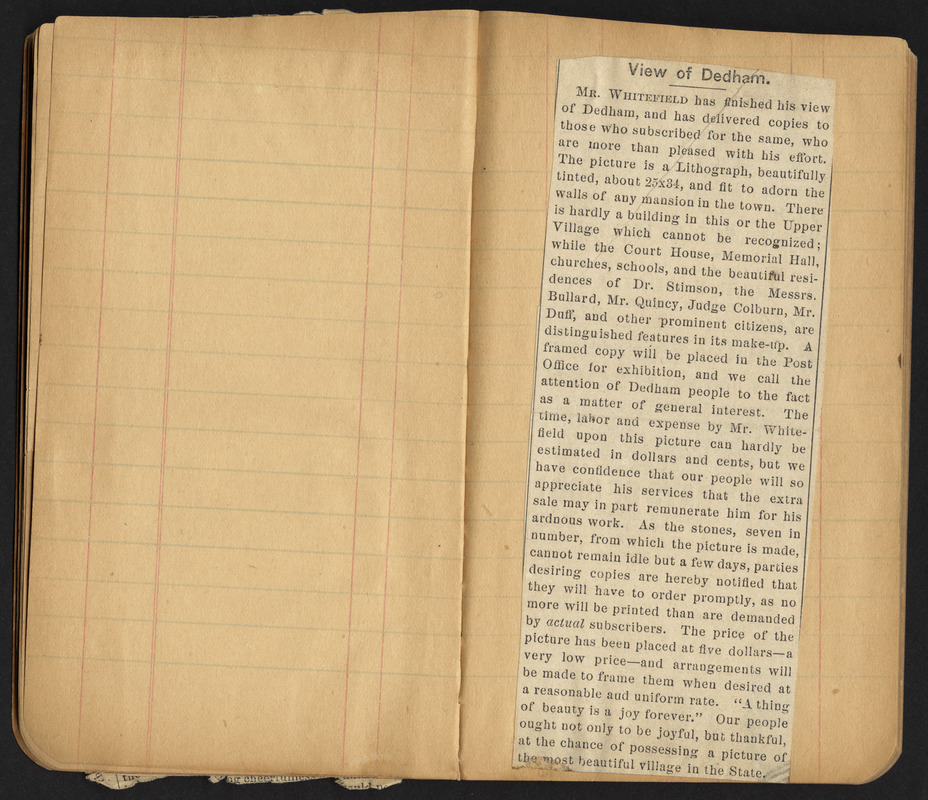

Edwin Whitefield (1816-1892)

“[Notice for] View of Dedham,” in scrapbook entitled Notices of My Views, Books, etc, ca. 1854 – 1876.

Boston Public Library, Print Department, Whitefield Collection

A notice pasted into a small scrap book announced the publication of the view. It indicated that the published view was distributed to the subscribers who “were more than pleased with his efforts.” The advertisement also advised other potential purchasers to order promptly, because the seven lithograph stones which were used to print the view could "not remain idle more than a few days” and “no more will be printed than are demanded by actual subscribers.”

As a means of enticing further sales, he stated that the “beautiful residences” of several prominent citizens were “distinguished features in its make-up.” In a final promotional appeal, he remarked, “Our people ought not only to be joyful, but thankful, at the chance of possessing a picture of the most beautiful village in the State.”

Franklin View Company

City of Cambridge, Mass.

Boston, 1877

Oriented with north at the top, this view includes all of Cambridge. The original village center focusing on Harvard Square and Harvard University is positioned just left of center. Cambridgeport with its numerous commercial activities is clustered around Central Square, and the industrial activities of East Cambridge are located in the upper right hand corner of the drawing.

Several brickyards are prominently displayed on the left side of the view. Meanwhile, the city’s largest employer, the New England Glass Company, appears in the upper right hand corner, north of the Boston and Lowell Railroad.

The Franklin View Company combined elements of a conventional map with the currently popular bird’s eye view. The street pattern was replicated with little distortion, but the buildings were shown in three dimensions and the horizon displayed a high oblique perspective.

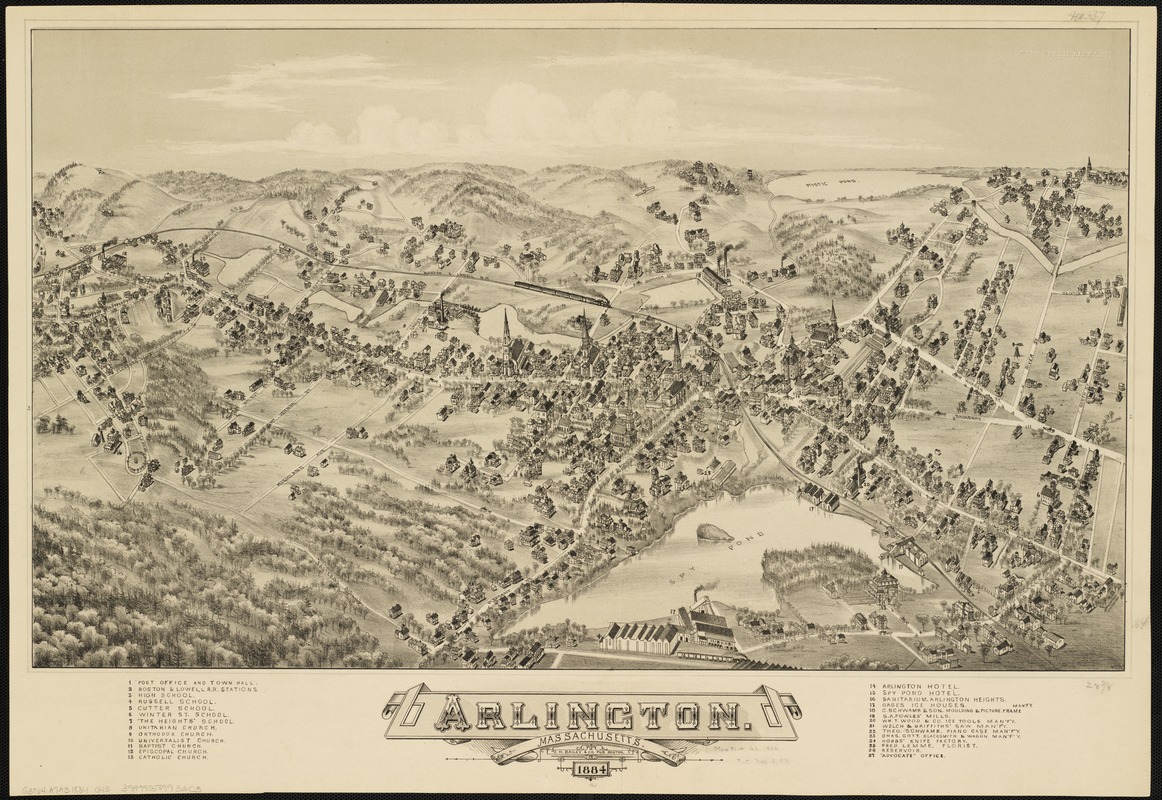

Oakley H. Bailey (1843-1947)

Arlington, Massachusetts

Boston, 1884

In this composition, Arlington is depicted at the height of its industrial activity and as it was starting to become a residential suburb of Cambridge and Boston. Almost all the churches and the town hall are located in the center of the drawing, focusing attention on the residential portion of the community.

Spy Pond, appearing in the center foreground, was the location of Arlington’s most important ice cutting and shipping industry. The other six industries were located near mill ponds that flowed into Mystic Pond.

Known as Menotomy throughout the colonial period, Arlington was settled in 1635. It saw extensive military action in the opening battle of the Revolutionary War. In 1807, it was incorporated as a separate town, called West Cambridge, but was renamed Arlington in 1867 in honor of the soldiers buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Oakley H. Bailey (1843-1947) and [Albert E. Downs]

City of Malden

Boston, 1881

This view celebrates Malden’s incorporation as a city in 1881. “City Hall” was identified as number one in the legend and was positioned near the center of the drawing.

The city is viewed from the south, looking north along the Malden River. With a population of more than 12,000 at the time, the city was both an industrial center and a residential suburb. The legend identifies twenty-eight structures, including six factories that manufactured rubber shoes, sand and emery paper, and leather goods.

The legend also identifies nine churches, four schools, a post office, a public library, and seven railroad stations on the two rail lines. Together with a horse-drawn street car line running along Main and Pleasant Streets these structures give proof of the city’s identity as a residential suburb.

Oakley H. Bailey (1843-1947)

View of Watertown, Mass.

Boston, 1879

In 1879, Bailey published a view of Watertown, using a format and style similar to the Newton view. However, he changed the orientation and depicted the town from the southwest (Newton side of the river), looking northeast.

Watertown’s economy is shown in this view, as diversified and with its own industrial base. The legend identifies eighteen important structures including two factories, a stock yard, two banks, two hotels, a railroad station, five churches, and a number of public buildings.

The Watertown Arsenal, not included in this view, was a major U.S. Army installation for the storage and manufacture of munitions from 1816 to 1968. The only hint of its existence is the street named Arsenal Road running by the stockyard.

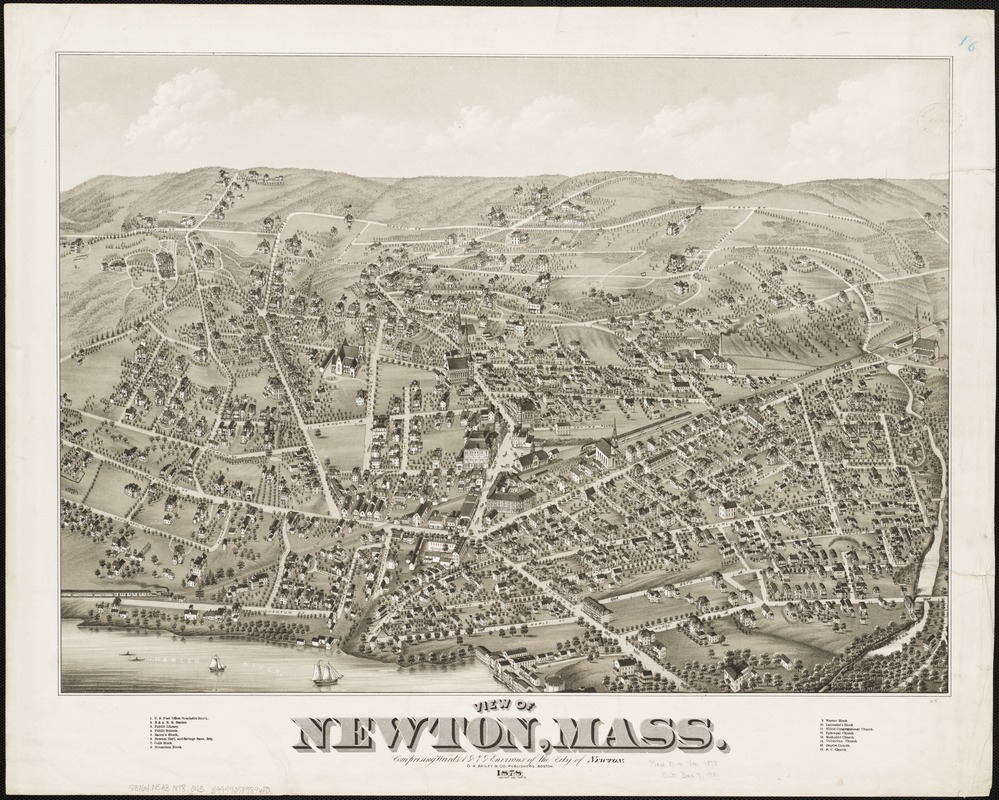

Oakley H. Bailey (1843-1947)

View of Newton, Mass., Comprising Wards 1 & 7 & Environs of the City of Newton

Boston, 1878

Towns located on rivers were often viewed from the river. For example, O.H. Bailey prepared separate views of Newton and Watertown, which were located opposite sides of the Charles River. In each view, he placed the river in the foreground.

In this image, the village of Newton Corner is depicted from the northeast (or Watertown) side of the river. It was the oldest of thirteen villages comprising Newton Township, which was incorporated in 1688. Most of these villages developed during the 19th century as residential suburbs of Boston.

The residential character of the village is evident in this view. The legend identifies sixteen prominent structures, but none of them are factories. In the 1960s, the Massachusetts Turnpike was constructed along the Boston and Albany Railroad’s right of way, resulting in the division of the village into two separate parts.

Oakley H. Bailey (1843-1947)

View of Waltham, Mass.

Boston, 1877

This view of Waltham emphasizes the town’s location straddling the Charles River. The central focus of the image is the town’s two major industries, the Boston Manufacturing Company and the American Watch Company.

Located on the Charles River eight miles west of Boston, Waltham is often called the true birthplace of America’s Industrial Revolution. Although Waltham was incorporated as a separate town in 1738, it was primarily a farming community until 1814 when Francis Cabot Lowell built the first integrated textile factory in America, incorporating both spinning and weaving into the same location. The twelve-foot waterfall in Waltham was used to power this factory.

Accentuating this sense of prosperity, the view also prominently displays five churches, which appear to be drawn out of proportion to the town’s other structures.

5. Coastal Towns

New England’s urban network developed within two different physical landscapes – at the edge of the ocean shore and along interior rivers and streams. These settings provided the basis for towns with different economic activities.

Arriving primarily from England, the first European settlers established their towns and villages along the coastline, taking advantage of the many well protected harbors. Seaports and fishing communities prospered in these locations. During the colonial period, these coastal communities developed an active maritime trade, carrying goods to and from England, the Caribbean, and the other British North American colonies. In addition, shipping, fishing, and whaling became important occupations. These pursuits prospered well into the 19th century, but declined as the swift clipper ships were replaced by steamships and whale oil was replaced with petroleum products.

As maritime activities diminished in the coastal towns during the last half of the 19th century, some of these communities turned to industry, building factories on the small tributary streams feeding into the harbor or utilizing steam power. Others, especially those on the Cape and the Islands, became summer resorts, offering a relaxing haven for the nation’s and the region’s wealthy citizens.

It was during this transitional period, that the bird’s eye view artists captured New England’s coastal towns. The artists typically viewed the towns from the water as if approaching from the sea, emphasizing their maritime activities. Orienting the views from a seaward approach meant that most did not have north at the top of the page.

E.H. Bigelow and James C. Hazen (1852-1908)

Newburyport, Mass., 1880

[Boston], 1880

Incorporated as a town in 1763, Newburyport is located near the mouth of the Merrimack River. It flourished as a center for shipping, shipbuilding, and whaling during the colonial period and as a port for privateering during the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812.

During the 19th century, shipbuilding continued to be an important, but declining, activity. In the 1830s and 1840s, the town’s economy became more industrialized with the establishment of four textile mills, a distillery, an iron foundry, and several other factories which produced shoes and combs.

This view’s perspective highlights the town’s waterfront, suggesting its former reliance on maritime activities. The artists have also used significant vertical exaggeration to accentuate the height and importance of the industrial buildings, the churches, and other public buildings.

Franklin Lithograph Co.

City of Gloucester, Mass.

Boston, [1873?]

Gloucester was established as a town in 1642 and incorporated as a city in 1873. By the middle of the 18th century it was an important shipbuilding center, especially known for its schooners. It also developed a major fishing industry, as the town’s fishermen exploited the resources of the Grand Banks off the coast of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. These activities continued to be important throughout the 19th century.

Viewed from a conventional cartographic perspective with north at the top of the sheet, this late 19th-century drawing is dominated by Gloucester’s superb natural harbor. There is no evidence of heavy industrial activity and most of the businesses pertain to maritime activities. John Pew and Sons, became the town’s most famous seafood business, eventually known as the Gorton-Pew Fisheries and currently, Gortons of Gloucester.

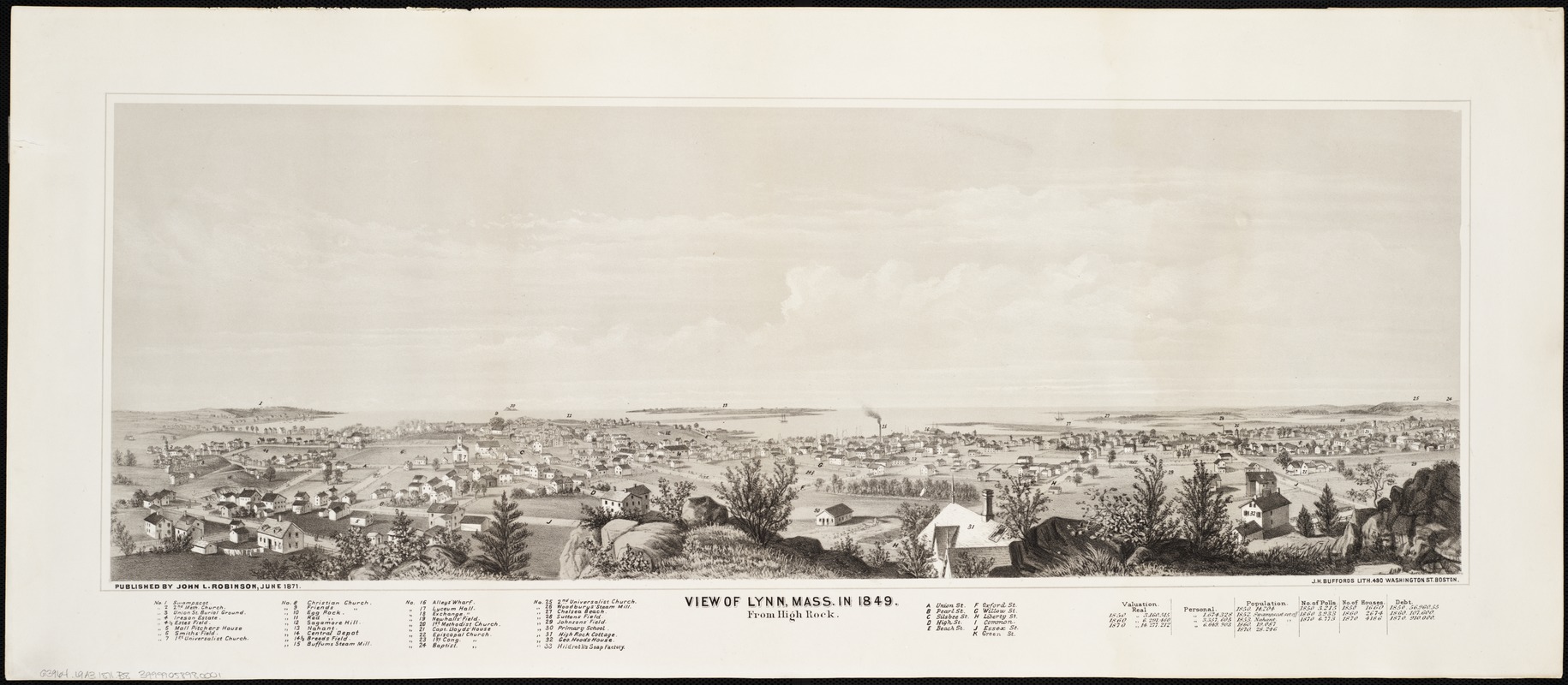

[Edwin Whitefield] and John L. Robinson

View of Lynn, Mass. in 1849, from High Rock

Boston, 1871

Drawn from a low-angle perspective and an inland vantage point, this view was not typical for coastal towns. However, as the harbor fades into the horizon, the view recalls Lynn’s colonial origins as a coastal port.

This view appears to be an historical recreation of the town as it existed in 1849. John Robinson, the publisher of this 1871 printing, added a legend and a table of population and real estate statistics from 1850 to 1870, documenting the community’s dramatic growth during the middle of the 19th century.

Of the thirty-three places identified in the legend, there is no mention of the shoe industry, which originated during the colonial period and continued through the first half of the 19th century as an in-home, handmade cottage industry until the introduction of the shoe-sewing machine in 1849.

Oakley H. Bailey (1843-1947) and James C. Hazen (1852-1908)

Manufacturing Center of Lynn, Mass.

Boston, 1879

This very typical bird’s eye view, created as a visual directory of the town’s “manufacturing center”, was published by O.H. Bailey in 1879. It provides a high elevation perspective of Lynn, viewing it from the southeast as if approaching from the sea.

Although the city’s waterfront is in the foreground, it does not appear to have been very busy. The viewer’s attention is drawn to the center of the drawing where a large concentration of factories is clustered along Central Street between Central and Park Squares.

Until the end of the 19th century, Lynn was noted as the nation’s leading producer of shoes, especially women’s shoes. This reputation is confirmed by the view’s legend citing thirty-one shoe manufacturers out of forty-one industries. Thirty-one of these were listed as makers of boots and shoes, while an additional seven were shoe-related industries.

Oakley H. Bailey (1843-1947)

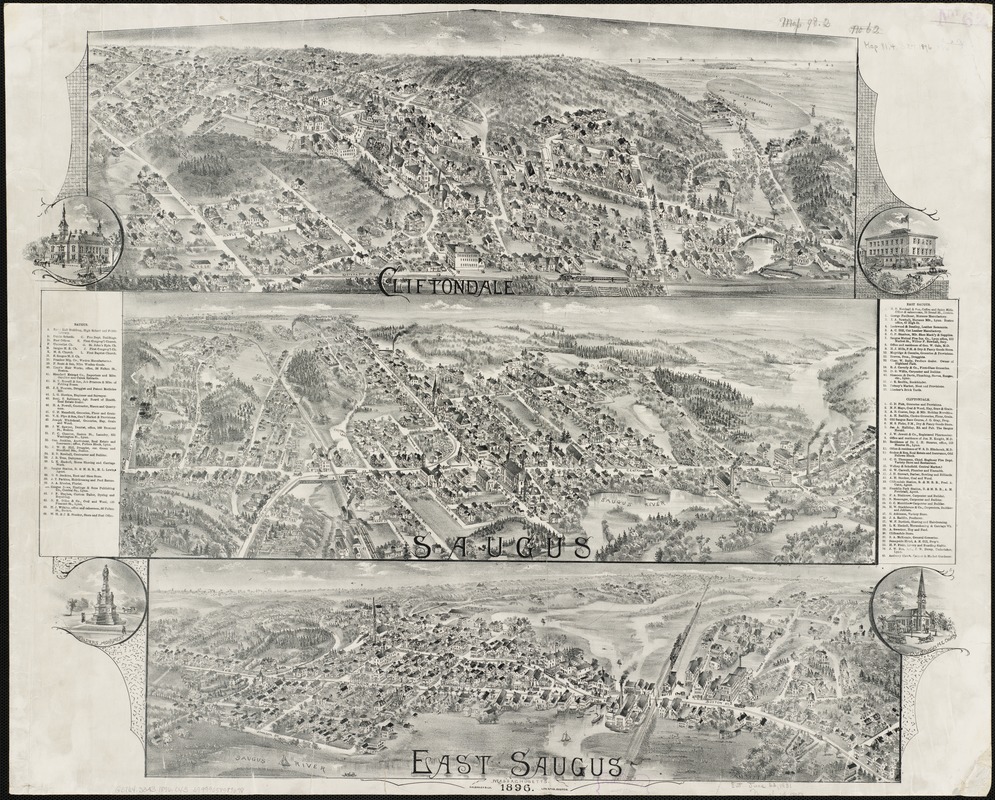

Cliftondale, Saugus, East Saugus, Massachusetts

Boston, 1896

This very unusual single image consists of three separate bird’s eye views of equal size, and different orientations.

The view depicts the neighboring villages of Cliftondale, Saugus, and East Saugus, all located in the town of Saugus. The former is viewed from the west, while the other two are viewed from the east. Despite the disparate perspectives, the railroad displayed prominently in each view provides a unifying element. The same rail line passed through all three villages.

Saugus was first settled in the early 17th century, and the town was established in 1815. At that time, the town’s economy was based primarily on agriculture. This view lists an extensive directory of churches, public buildings, commercial businesses, and factories, within these three communities.

Oakley H. Bailey (1843-1947)

Plymouth, Mass.

Boston, 1882

Most people remember Plymouth as the landing place of the Pilgrims in 1620 and as the first permanent English settlement in New England. However, this late 19th-century view documents an historic town that transformed itself from a small coastal port into an industrial town with a diversified base.

As if recalling the Mayflower’s approach from the sea across Cape Cod Bay, the artist views the town from the northeast looking inland toward the southwest. Using this perspective, he emphasizes not only the harbor and waterfront activities, but also the location of six major industrial complexes running through the center of the drawing.

Six vignettes of factories and several historic monuments are also identified in this view.

Oakley H. Bailey (1843-1947)

View of the City of New Bedford, Mass.

[Boston], 1876

Founded in the late 18th century, New Bedford became the nation’s leading whaling port but following the 1859 discovery of petroleum in Pennsylvania, the town invested its fortunes in a growing textile industry.

Placement of the seaport’s waterfront in the foreground pays homage to the town’s economic activity during the first half of the 19th century, but also reflects its transition to an industrialized economy. Prominently featured are the town’s two new cotton textile factories – the Potomska and Wamsutta Mills. By the end of the 19th century, Wamsutta Mills became the nation’s largest cotton weaving factory.

The image’s legend identifies the many public buildings that served this community whose population in 1880 was 27,000. The variety of churches provides some evidence of the many immigrants who came to work in New Bedford.

[Oakley H. Bailey] (1843-1947)

Providence, R.I.

Boston, 1882

In 1880 Providence had a population of almost 105,000, making it the 20th largest city in the United States. This drawing focuses attention on the harbor facilities along the Providence River in the foreground and center portions of the image. Union Depot is prominently located near the center of the map.

Such an orientation suggests the importance of transportation and shipping to the city’s economy. Although shipping was an important aspect of Providence’s economy during the colonial period, the city was one of the earliest in America to be industrialized. By the 1830s, the city’s economy was dominated by several different types of manufacturing – base metals and machinery, cotton and woolen textiles, and jewelry and silverware.

The legend identifies more than one hundred structures, most of which were industrial, transportation, or commercial enterprises.

John P. Newell (ca. 1831-1898)

Newport, R.I., View from Fort Wolcott, Goat Island

[Boston, ca. 1860]

This low elevation landscape view focuses on Newport’s harbor, which is filled with a variety of sailing vessels. It emphasizes the town’s importance as a seaport, especially during the colonial period.

As the town’s maritime fortunes declined after the Revolutionary War, it became a summer resort for southern plantation families and Boston artists and scholars, and by the end of the century, for the wealthy industrial elite of the Gilded Age.

Newell’s view, drawn just before the Civil War began, represents a traditional landscape view. It portrays the facades of buildings as viewed from a ground level perspective. It also provides a skyline panorama, accentuating the tallest buildings, especially the church steeples. The large building on the horizon is the Ocean House, one of the hotels catering to summer visitors.

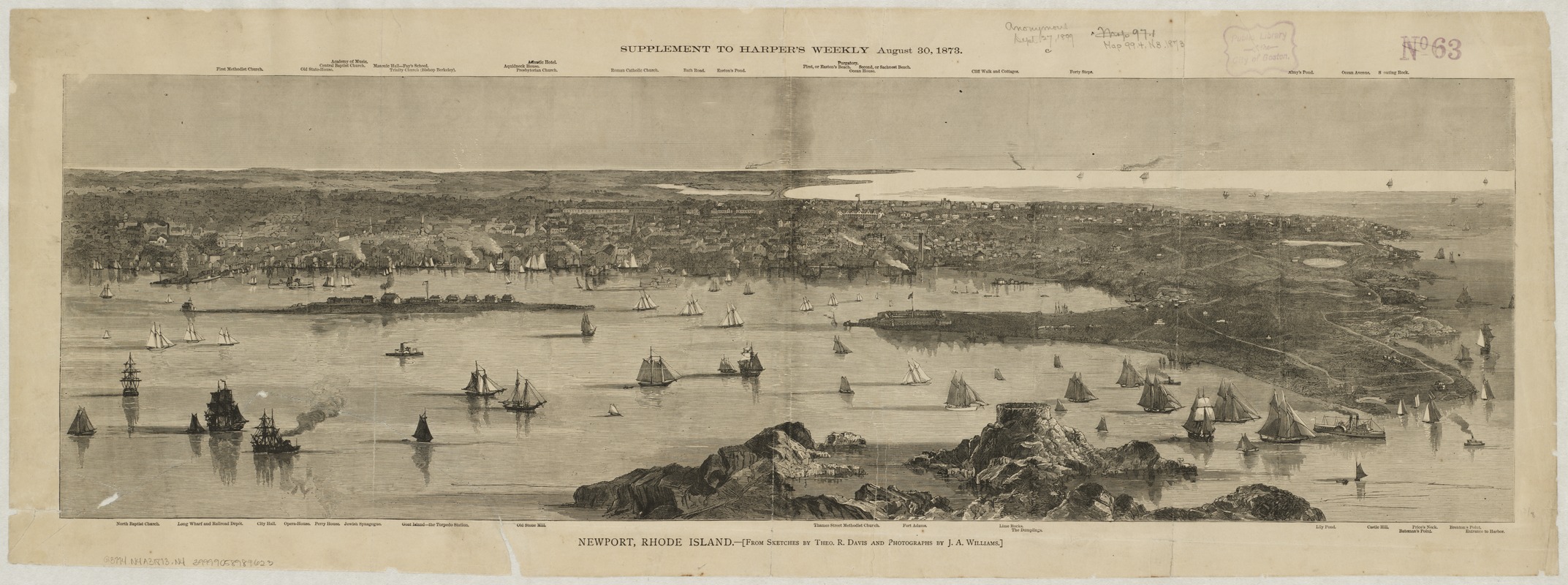

Theodore R. Davis and J.A. Williams

Newport, Rhode Island

[New York], Supplement to Harper’s Weekly, August 30, 1873

A second view portrays Newport from a slightly higher elevation. It provides a broader geographical context, illustrating Newport’s location on the southwestern side of Aquidneck Island.

Published with an article in Harper’s Weekly, it depicts the town from a low to moderate oblique perspective. The street pattern is not drawn and many buildings are generalized. The more prominent ones are identified along the upper and lower margins.

Sailing vessels and steamships, the torpedo station, and Fort Adams provide evidence of the community’s maritime and military significance. The town’s growing reputation as a fashionable “watering place” is shown by the identification of several hotels in the central part of the town and the march of summer “cottages” along the Cliff Walk and Ocean Avenue, on the opposite side of the island.

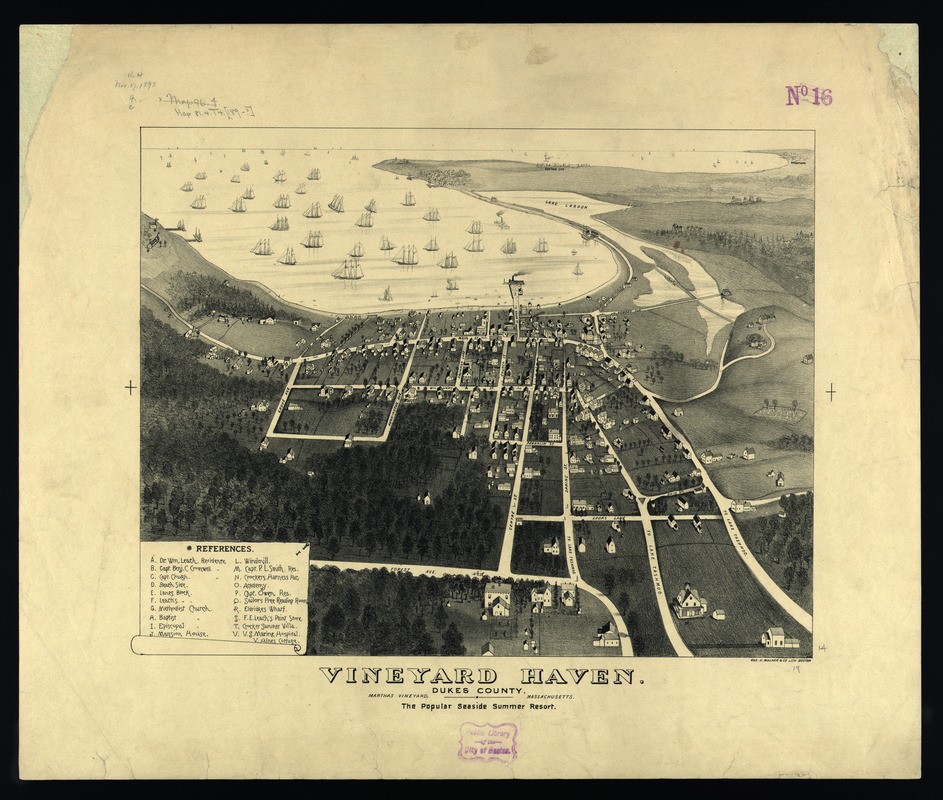

[George Walker]

Vineyard Haven, Dukes County, Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts

Boston, [1893]

This image of Vineyard Haven focuses on the community’s waterfront, which is dotted with many sailing vessels. The drawing is subtitled, “The Popular Seaside Summer Resort,” suggesting the island’s new role as a summer resort. However, it provides ample evidence of the town’s earlier reliance on maritime activities, including two other wharves on the left, a sailor’s free reading room, a U.S. Marine Hospital, and four ship captain’s residences.

Vineyard Haven, the second largest village on Martha’s Vineyard, is the primary village in the town of Tisbury and it still serves as the primary port for ferries bringing summer visitors from the mainland.

Visible in the background are the island’s two other important villages – Edgartown and Cottage City. The latter, now known as Oak Bluffs, originated during the 1830s as a summer location for Methodist revivalist camp meetings.

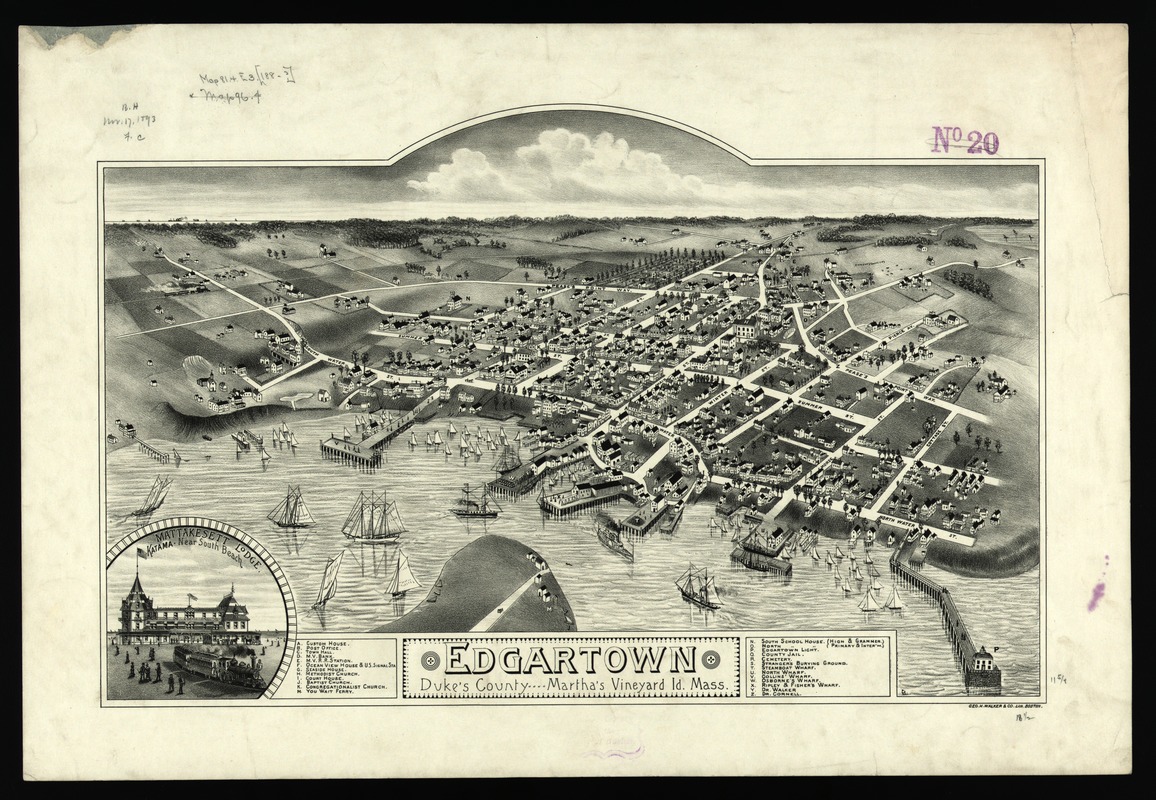

[George Walker]

Edgartown, Duke’s County, Martha’s Vineyard Id., Mass.

Boston, [1886]

This view is reminiscent of Edgartown’s former glory as a whaling port. Its most prominent structures are five major wharves and the lighthouse that guided ships into the harbor. During the first half of the 19th century, this community was one of New England’s major whaling ports. Following the Civil War the town’s fortunes declined as the need for whale oil was replaced by petroleum products.

Running parallel to the shore is Water Street, which is densely populated with businesses and residences. Many of the larger houses were built by prosperous ship captains in the 1830s and 1840s.

By the 1880s, Edgartown, as well as the entire island, was emerging as a major summer resort.

Albert F. Poole

Bird’s Eye View of the Village of Hyannis, Barnstable County, Mass.

Brockton, Mass., 1884

Using an unorthodox perspective for a coastal location was a symbolic means of showing the economic changes that were occurring in this and other Cape Cod communities during the last half of the 19th century. While fishing and maritime activities continued to be important, these communities were becoming fashionable summer retreats for wealthy citizens of Boston, Providence, and other inland New England towns.

Hyannis is the largest of the seven villages in the town of Barnstable. Incorporated in 1639, the town straddles the “bicep” of Cape Cod. The early settlers of this area were farmers, but during the 18th and 19th century, the town’s inhabitants supported themselves primarily by maritime activities.

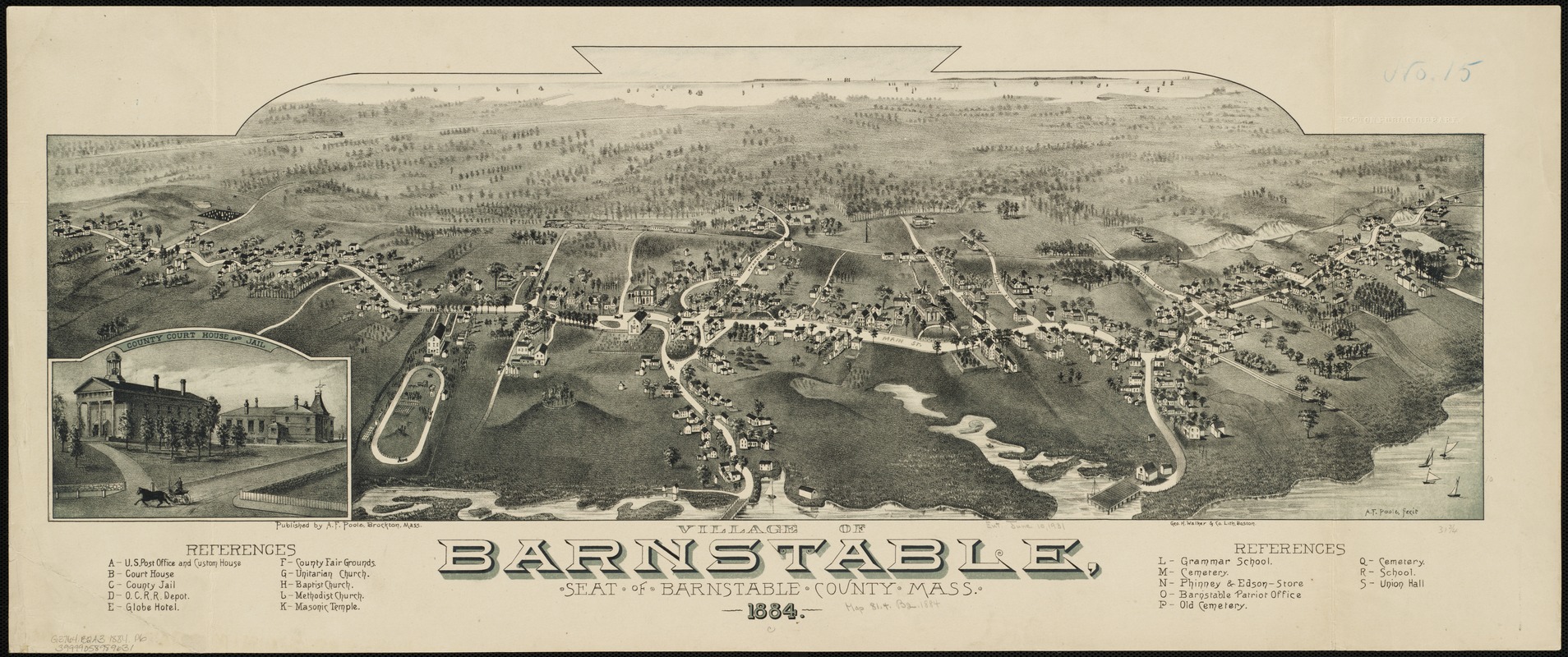

Albert F. Poole

Village of Barnstable, Seat of Barnstable County, Mass.

Brockton, Mass., 1884

The village of Barnstable is located on the northern coast of Cape Cod. Drawn by the same artist and published in the same year as the view of Hyannis, this view’s background extends south across the peninsula towards Hyannis. Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard are faintly visible on the horizon.

This small village, displaying a linear settlement pattern, serves as the county seat for Barnstable County, which includes all of the towns on the Cape. The view’s central focus is Main Street. Also highlighted are the village’s administrative and governmental functions as well as the county fairgrounds.

Interestingly, the Old Colony Railroad, which was prominently featured in the Hyannis view, is also shown in this view. It runs the length of the drawing, located just south of town, heading towards Hyannis and the southern shore line.

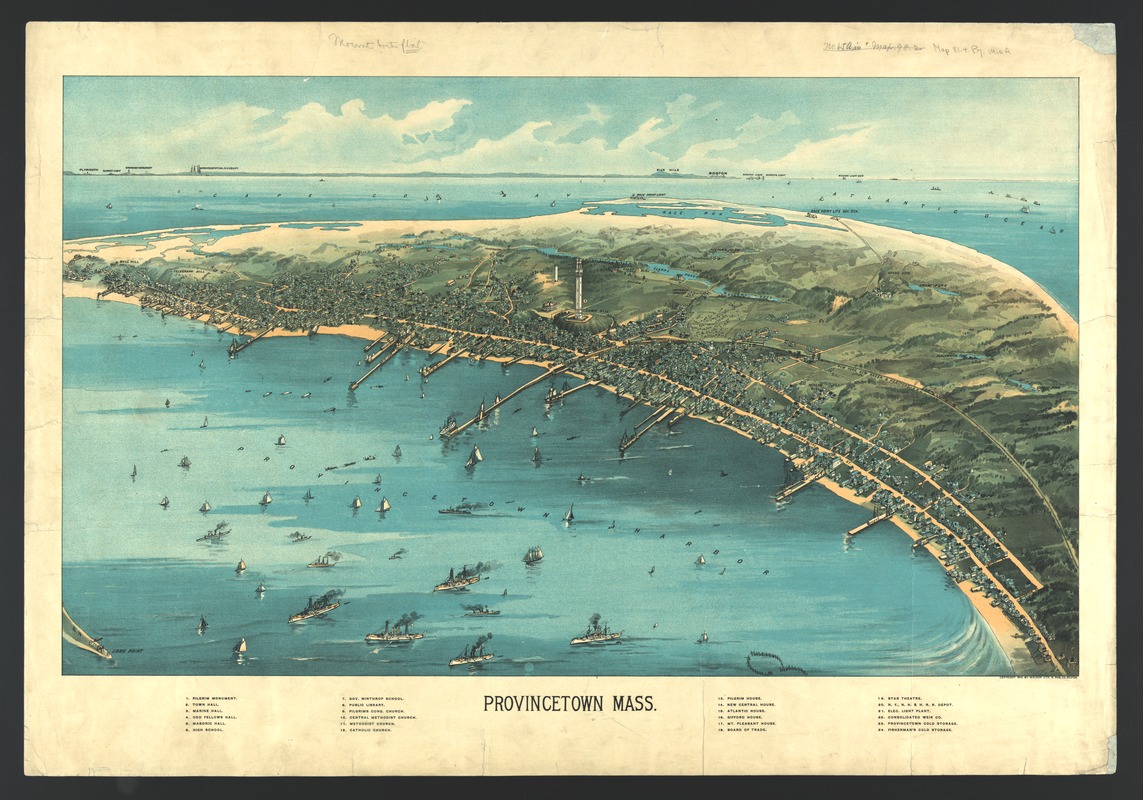

[George Walker]

Provincetown, Mass.

Boston, 1910

Looking in a northwesterly direction toward Cape Cod Bay and the distant Boston shoreline, this bird’s eye view portrays Provincetown at a time when the town was transitioning from a community dependent on fishing to one whose economy and culture were increasingly tied to the seasonal influx of summer residents and a growing artist’s and writer’s community.

The central focus of this view is Provincetown’s most striking architectural feature – the Pilgrim Monument, completed in 1910, the year of this view. The monument was built to commemorate the Mayflower’s five-week stay at the tip of Cape Cod before the Pilgrims decided to shift their base to Plymouth Bay.

Numerous wharves, harbor ships, and three processing plants for fish reflect the town’s reliance on maritime activities during the 19th century. The identification of several hotels foreshadows the town’s developing tourist industry.

6. Inland Towns

As Boston became New England’s primary port, European settlement spread inland from the coastal villages and towns, in a pattern that followed the Charles, Merrimack, Blackstone, and Connecticut Rivers. Initially, as new townships were established, the primary inland settlements were small agricultural villages. With the advent of the industrial revolution at the end of the 18th century and during the first half of the 19th century, some of the earliest factories were constructed near water power sites on the small, fast flowing rivers and tributary streams by these villages. With the construction of canals and railroads to connect these villages to Boston and the adoption of steam powered engines to run the factories, many of these villages grew into major industrial towns during the last half of the 19th century.

It was during the height of this industrial activity, which was tied to railroads and steam powered engines, that the bird’s-eye view artists documented a very large number of southeastern New England’s inland cities, towns, and villages. The artists had no rule books, but they often depicted these communities by placing emphasis on the rivers, the railroads, and the associated factories. No specifications or guidelines told the artists what to include or leave out. They only needed to satisfy the city fathers who commissioned the project and the town’s upper and middle classes, who would become the potential buyers of the published views. Consequently, these bird’s eye views became “Chamber of Commerce” documents promoting local industrial or commercial activities.

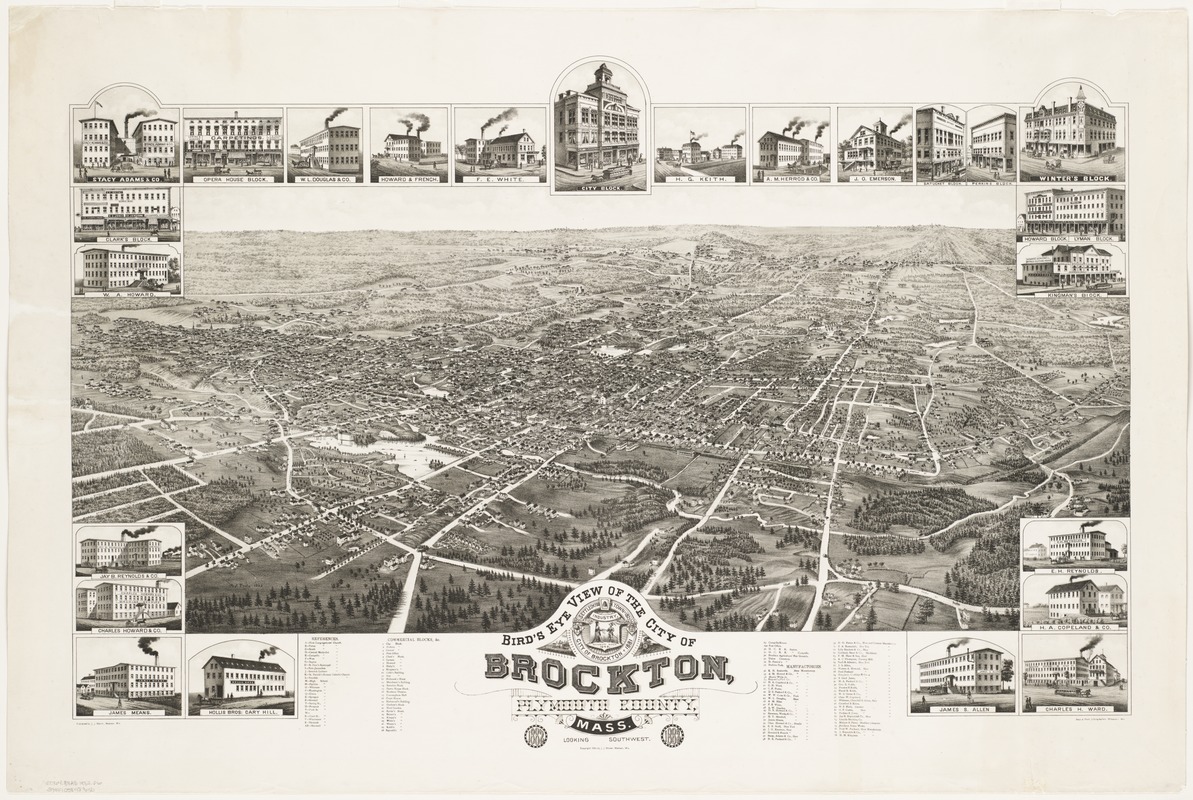

Albert F. Poole (1853-1934)

Bird’s Eye View of the City of Brockton, Plymouth County, Mass., Looking Southwest

Madison, Wis., 1882

Albert Poole, a native son of Brockton, drew this view of his home town one year after it was incorporated as a city. Originating as a small farming village, the community was included in the town of North Bridgewater when it was established in 1821.

Before the Civil War, the village became a center for manufacturing shoes and during the war it processed large orders of boots for the U.S. Army. The shoe industry continued to grow and, by the end of the 19th century, Brockton was the largest shoe-producing city in the United States. When Poole drew this image, the city had a population of approximately 14,000.

Poole started his career as a clerk and school principal in Brockton, but began producing bird’s eye views in 1880. This Brockton view was one of his earliest.

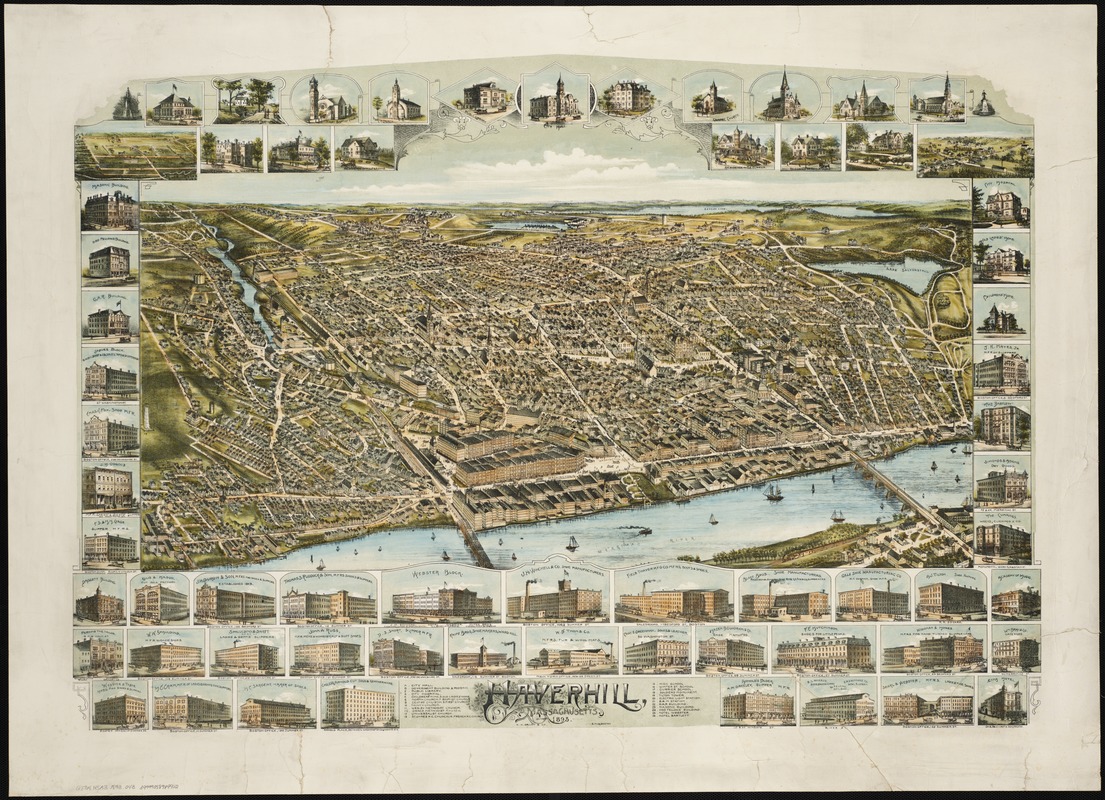

Oakley H. Bailey (1843-1947)

Haverhill, Massachusetts

Boston, 1893

In this colorful bird’s eye view, Haverhill, located on the north side of the Merrimack River, is depicted from the south. This composition focuses on the city’s waterfront and central business district.

However, the true nature of the city’s industrial and commercial activity is captured in the marginal insets. Of the 64 vignettes, 28 depict boot, shoe, and slipper manufacturers, while one portrays a hat factory. Next to Lynn and Brockton, Haverhill was the state’s third most important producer of footwear, primarily fine ladies’ shoes.

The marginal insets identify several public buildings, including the city hall, public library, and high school. Flanking these images are six churches. In addition, there are pictures of seven private residences, most likely of the city’s wealthiest citizens, but also the birthplace of poet, John Greenleaf Whittier.

Howard H. Bailey (1836 -1878) and James C. Hazen (1852-1908)

Bird’s Eye View of Lowell, Mass.

[Boston], 1876

Recognized as the first planned company mill town, Lowell was founded in the 1820s when a group of Boston financiers constructed a textile factory on a canal bypassing the Merrimack River’s Pawtucket Falls. This view depicts a densely settled city resulting from fifty years of industrial growth. According to the 1880 census, it was Massachusetts’ second largest city.

By viewing the city from the north, the artists were able to place the original industrial enterprise, the Merrimack Manufacturing Company, in the center foreground.

This view served primarily as a business directory with the legend listing sixty industrial and commercial activities.

The city’s social and cultural life was not highlighted. The view shows no sign of the vitality of the city’s ethnic neighborhoods that characterized the city’s work force during the last half of the 19th century.

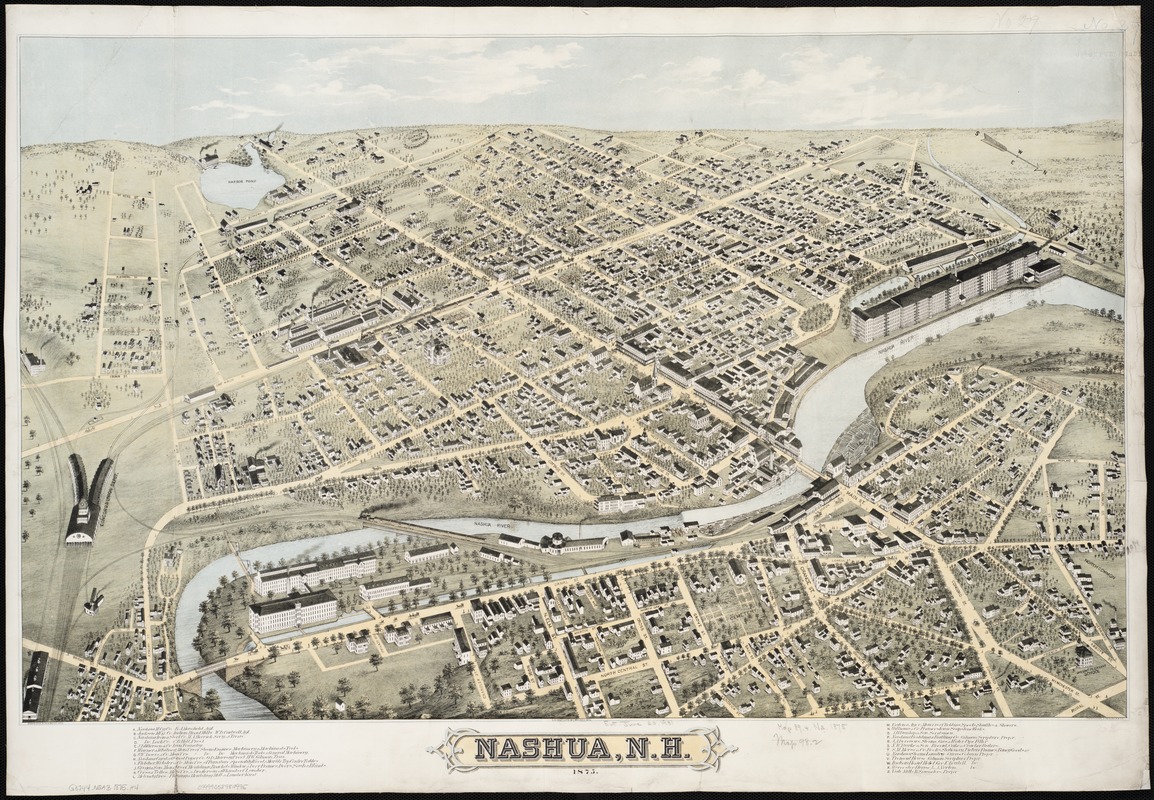

Howard H. Bailey (1836 -1878)

Nashua, N.H.

[Boston], 1875

Nashua, an industrial town located at the juncture of the Nashua and Merrimack Rivers in southern New Hampshire, was recorded on two bird’s eye views. The first was published in 1875 by Howard H. Bailey, and the second by his brother Oakley in 1883.

In the former, Howard views the city from the north, giving prominence to two large textile mills, the Nashua Manufacturing Company on the right and the Jackson Manufacturing Company’s Indian Head Mills on the left.

What makes this drawing especially interesting is the railroad station, labeled as the Concord and Union Depot and prominently displayed on the left side of the drawing. It was apparently based on plans supplied by the railroad company, but not constructed as planned, resulting in Howard being criticized in the local press for this misrepresentation.

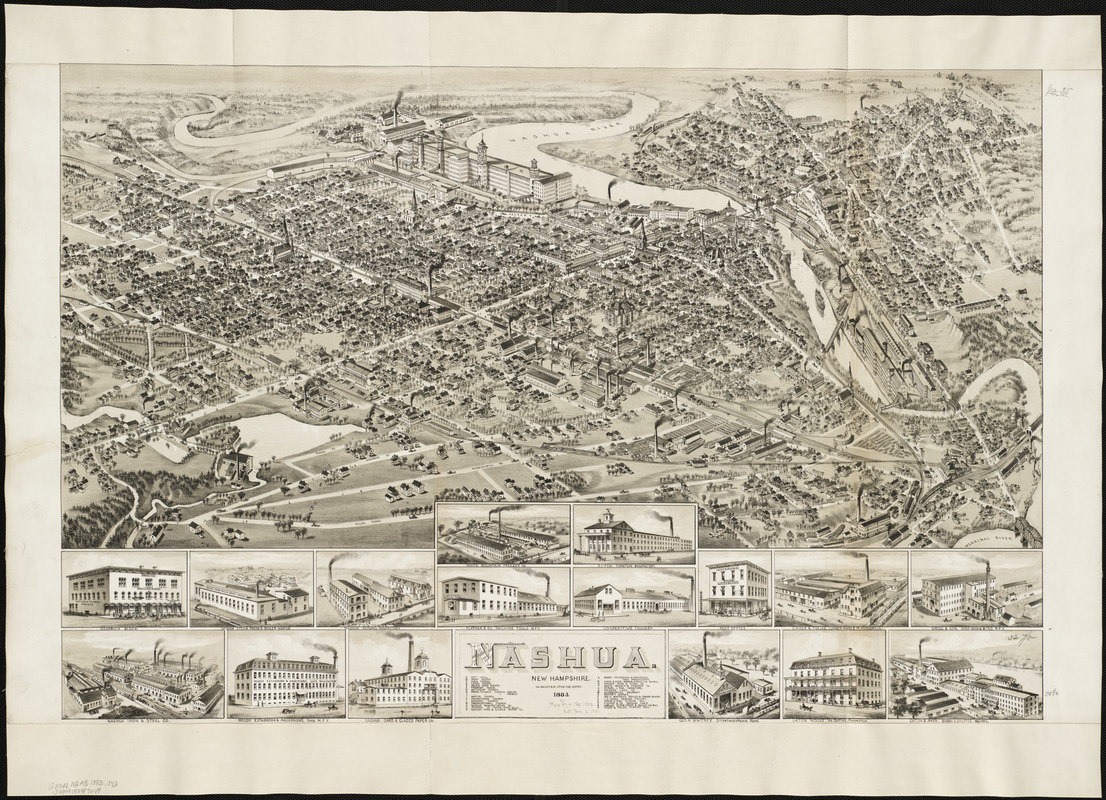

Oakley H. Bailey (1843-1947)

Nashua, New Hampshire

Boston, 1883

Oakley was most likely aware of his older brother’s rendition, since they often worked together. However, Oakley re-orients his presentation, viewing the town from the southeast. He depicts a totally different train station and relegates it to the lower right corner, neither displaying it prominently nor labeling it.

His brother had included a legend identifying twenty-four important structures, primarily factories and commercial buildings but no public buildings. Oakley expands his legend to identify thirty structures, providing a more balanced coverage. His list includes city hall, the court house, a school, seven churches, three hotels, and seventeen factories.

Both drawings prominently display the two large textile complexes. In Oakley’s rendition, their relative positions are reversed with the Nashua Manufacturing Company appearing on the left and the Indian Head Mills on the right.

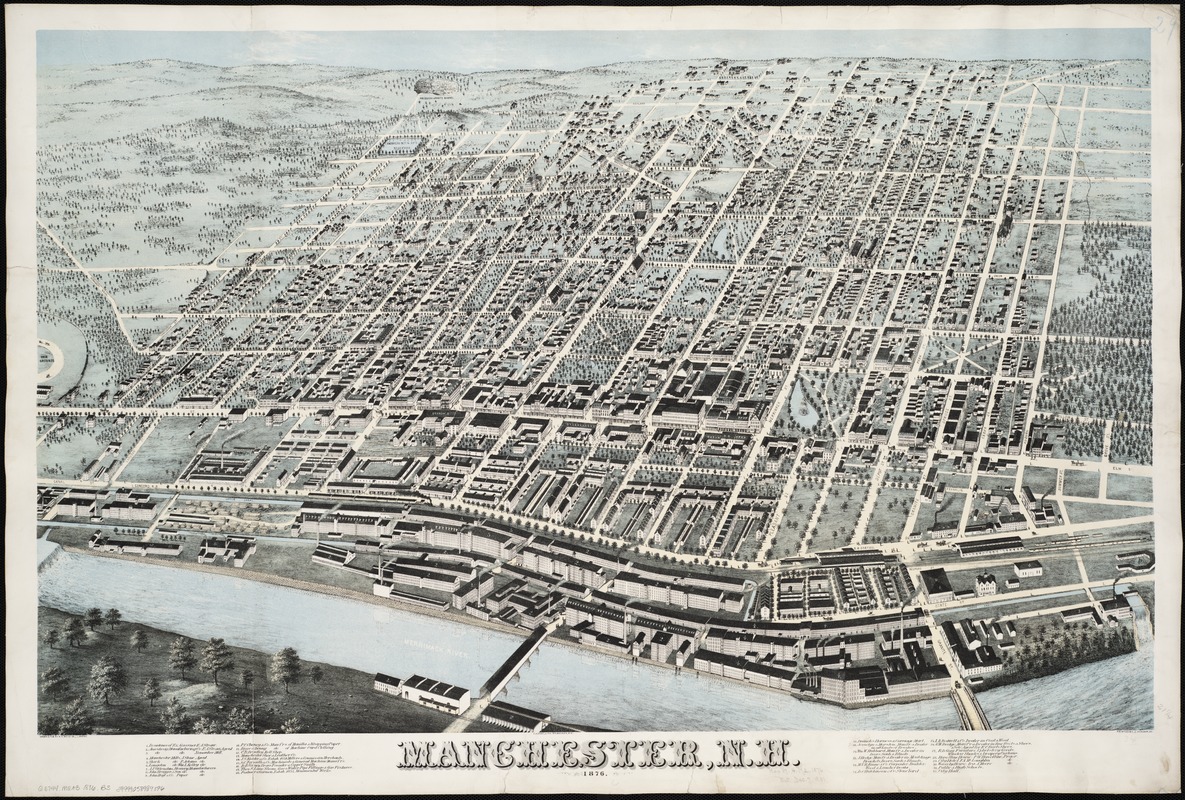

Howard H. Bailey (1836 -1878) and James C. Hazen (1852-1908)

Manchester, N.H.

[Boston], 1876

Located on the Merrimack River, Manchester is viewed from the west bank of the river looking east across the town. By using such an orientation, the artists were able to place the large number of factories located along the river and the parallel canal in the foreground.

Manchester’s Amoskeag Company was established in the 1830s with an influx of capital from Boston financiers. By the end of the 19th century, the company had grown to become the largest cotton textile manufacturer in the world.

The Amoskeag Company was also instrumental in establishing and planning the town. In contrast to most other New England villages, Manchester was designed with a grid street pattern. The plan included wide tree-lined streets and parks. Adjacent to the factories, the company also built long rows of tenement housing for the workers.

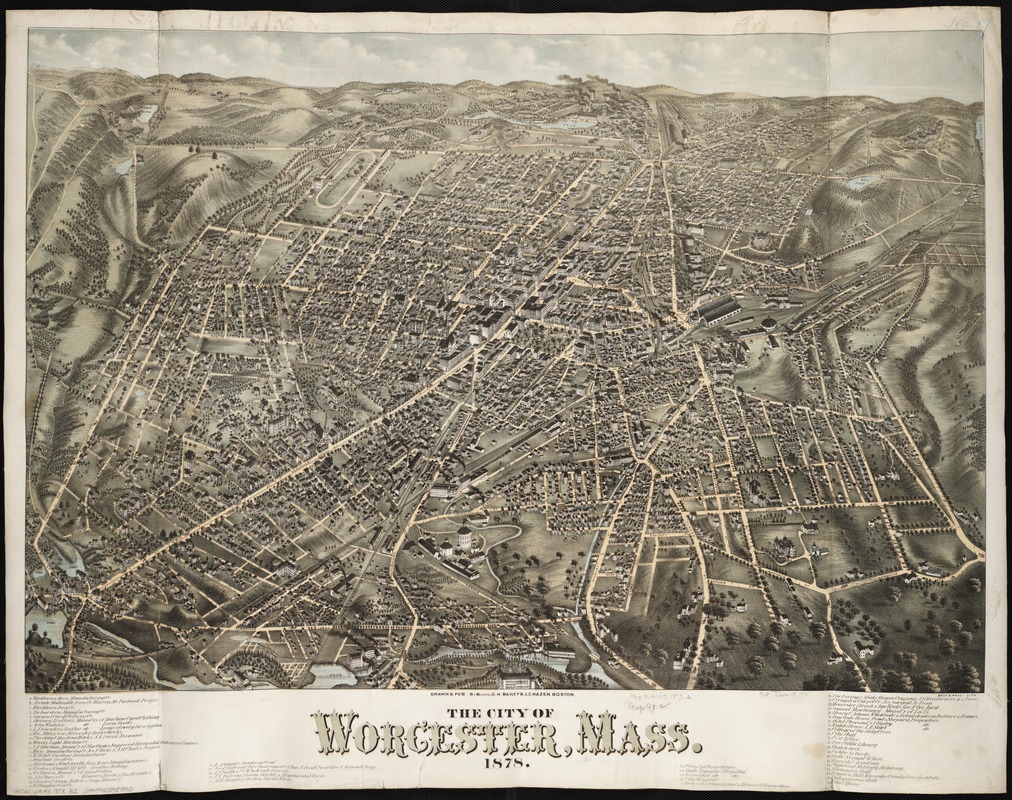

Howard H. Bailey (1836 -1878) and James C. Hazen (1852-1908)

The City of Worcester, Mass.

Boston, 1878

Worcester, the state’s third largest city in1880, is viewed from the south in this Bailey and Hazen view. Using this orientation, the artists place the central business district in the center portion of the drawing and illustrated three rail lines coming from the south converging in the center foreground of the drawing.

Worcester had a diversified industrial base, as evidenced by the thirty factories listed in the legend. Similar to other bird’s eye views published by Howard H. Bailey and Hazen, this one identifies no churches, although public buildings and colleges are listed.

The Washburn and Moen wire manufacturing industrial complex is given prominence in this view. Furthermore, two prominent streets – Main and Summer Streets – converge near the factory, drawing attention to its location on the center horizon.

Oakley H. Bailey (1843-1947)

View of Springfield, Mass.

Boston, 1875

Springfield, the largest city in western Massachusetts, is viewed from the southwest in this presentation. In composing this drawing, the artist placed in the foreground the waterfront, where a number of factories and the railroad yards were located.

The central business district includes the Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company and one of the city’s newspapers, the Springfield Republican. Both of these buildings were also pictured in one of the marginal insets, suggesting that either one or both may have been sponsors of this view’s production.

Some of the city’s major industrial activities included the manufacture of railroad cars and guns. The latter activity centered on the Springfield Armory, established by the Federal Government in the 1790s (upper right quarter of the image), and the Smith and Wesson Company (just right of the central business district).

Howard H. Bailey (1836 -1878) and James C. Hazen (1852-1908)

Bird’s Eye View of Holyoke, Mass.

New York, 1877

Located on a bend of the Connecticut River adjacent to Hadley Falls, the industrial city of Holyoke is viewed from the southeast in this bird’s eye view.

Although settled in the early 18th century, large-scale industrial development did not become important in Holyoke until the late 1840s, when a group of Boston industrialists constructed a dam and canals and planned a company town. Laying out the town with a grid street pattern, these investors envisioned an industrial community comparable to Lowell or Lawrence.

While the grid pattern still displays many empty spaces, the legend contains forty-six entries, most of which were industries. Of these at least sixteen were paper mills, from which the community gained the nickname “Paper City.” Only one public building is identified – city hall. None of the four or five churches are identified.

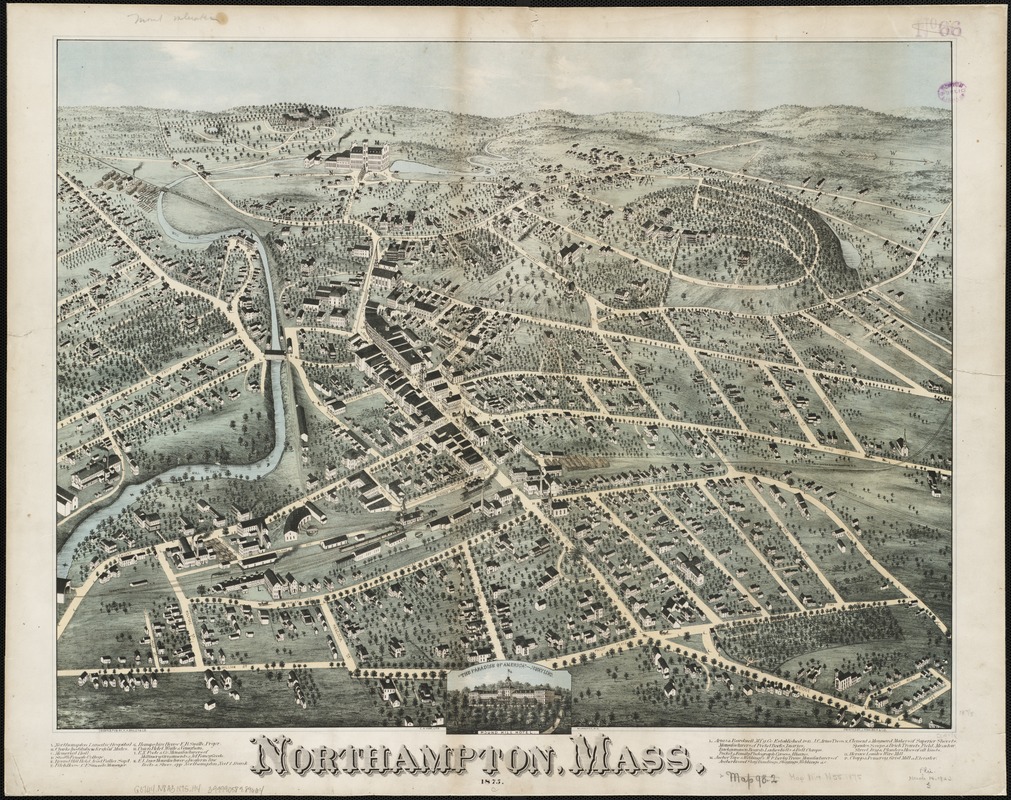

Howard H. Bailey (1836 -1878)

Northampton, Mass.

[Boston?], 1875

Located on the inside of a large meander of the Connecticut River, Northampton is viewed from the east with a vantage point above the river’s wide flood plain. Ignoring the river, the drawing is oriented toward the west, emphasizing its bucolic, hilly setting.

By the end of the 19th century, Northampton, originally an agricultural community, boasted a diversified economy. Most of its factories were located near the Mill River and the railroad track.

The legend also recognizes the city’s importance as a resort destination and the setting for specialized societal institutions. Located on the city’s fringes, these institutions included Smith Female College, founded in 1871 and now the nation’s largest liberal arts college for women; Clarke School for the Deaf, the nation’s oldest oral school for the deaf; and a lunatic hospital, now Northampton State Hospital.

Credits

We gratefully acknowledge the generosity of our supporters who continue to sustain us.

Muriel and Norman B. Leventhal

Associates of the Boston Public Library

Friends of Norman B. Leventhal

Sally and Bill Taylor

Massachusetts Transit Authority

Beehive Media LLC

Chan Krieger Sieniewicz, Inc.

Cabot Family Charitable Trust

Keefe Bruyette & Woods

Pyramid Hotel Group

Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities

Boston Rare Maps

Sovereign Bank

Liz and Robert Pozen

Cohen & Taliaferro, Inc.

MarketKing

In honor of the 90th birthday of Norman B. Leventhal

Irma and Seymour Andrus

Atlantic Trust

Nancy J. Broderick

William A. Bonn

Diane and Philip Brannigan

Karen and Rocco Ciampa

Cushman and Wakefield

John P. Fowler

Steven F. Fusi

Josette and Louis Goldish

Paula and James Gould

Goulston & Storrs

Henry and Sonia Irwig

Richard and Nancy Kelleher

Kathleen M. Laubenthal

Paul R. McDermott

Lisa A. Meomartino

Ann and Kenneth Morris

Adele and Andy Newman

The Penates Foundation

Adrienne and Mitchell Rabkin

Marcia and Al Scaramelli

Judith P. and S. Lawrence Schlager

Susan and Alan J. Schlesinger

Donna and Fred Seigel

Ellen and Kenneth Slater

Frederic E. Wittmann

Exhibit Curators:

Ronald E. Grim, Curator, Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

Roni Pick, Director, Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

Exhibit Design:

Andrea Janzen and Alex Krieger, Chan Krieger Sieniewicz, Inc.

Graphic Design:

Rena Sokolow, One2tree design

Exhibit Interactive

Beehive Media LLC

Conservation for all maps in this exhibit has been underwritten by a grant from Save America’s Treasures, administered by the National Endowment for the Humanities, and matched by an Anonymous donor.

All cartographic materials have been imaged by the Digital Imaging Lab of the Boston Public Library, under the direction of Tom Blake and Maura Marx

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center Board of Directors

Norman B. Leventhal, Founder

Robert M. Melzer, Chair

Richard Brown

Larry Caldwell

Norman Fiering

William M. Fowler

Alex Krieger

Scott A. Nathan

Ronald P. O’Hanley

Paula Sidman

William O. Taylor

Robert F. Walsh

Ann Wolpert

Bernard A. Margolis, ex-officio

Jeffrey B. Rudman, ex-officio

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center Board of Review

Norman B. Leventhal, Founder

Alex Krieger, Chair

Larry Caldwell

Norman Fiering

William M. Fowler

Robert M. Melzer

Dan L. Monroe

Harold Osher

Michael Stone

Ann Wolpert

Trustees of the Library of the City of Boston

Jeffrey B. Rudman, Chair

Angelo M. Scaccia, Vice Chair

Zamawa Arenas

William M. Bulger

James Carroll

Donna M. DePrisco

Berthé M. Gaines

Raymond Tye

Karyn M. Wilson