Introduction

Boston was the metropolis of Great Britain’s North American colonies, with the largest population and one of the busiest economies of any urban center through the 1750s. It was also the leading producer of printed maps, including major milestones such as the first map printed in the colonies, as well as the earliest city map, battle plan, and map engraved on copper.

This exhibition brings together, for the first time in decades, a majority of these maps “made in Boston” in the century before the American Revolution. As a group they are remarkable for their contributions to geographical knowledge and often unconventional style.

These maps also afford a unique perspective on the ambitions, anxieties and sense of identity of colonial Bostonians: pride in their flourishing city, the hazards of navigating New England’s coast, disputes over land ownership, and struggle with the native inhabitants and French for mastery of North America.

1. Mapping New England

From the earliest days of settlement, New England comprised several semi-autonomous colonies. Each had its own government and to some degree its own culture, and at times they competed fiercely. Yet they shared an identity as “New Englanders,” responsible for establishing a foothold in North America, where they would be free to enjoy both the rights of Englishmen and the freedoms and material wealth of the New World. This regional identity is evident from some of their earliest maps, which reveal their attempts to impose order on a vast, mysterious and often terrifying wilderness.

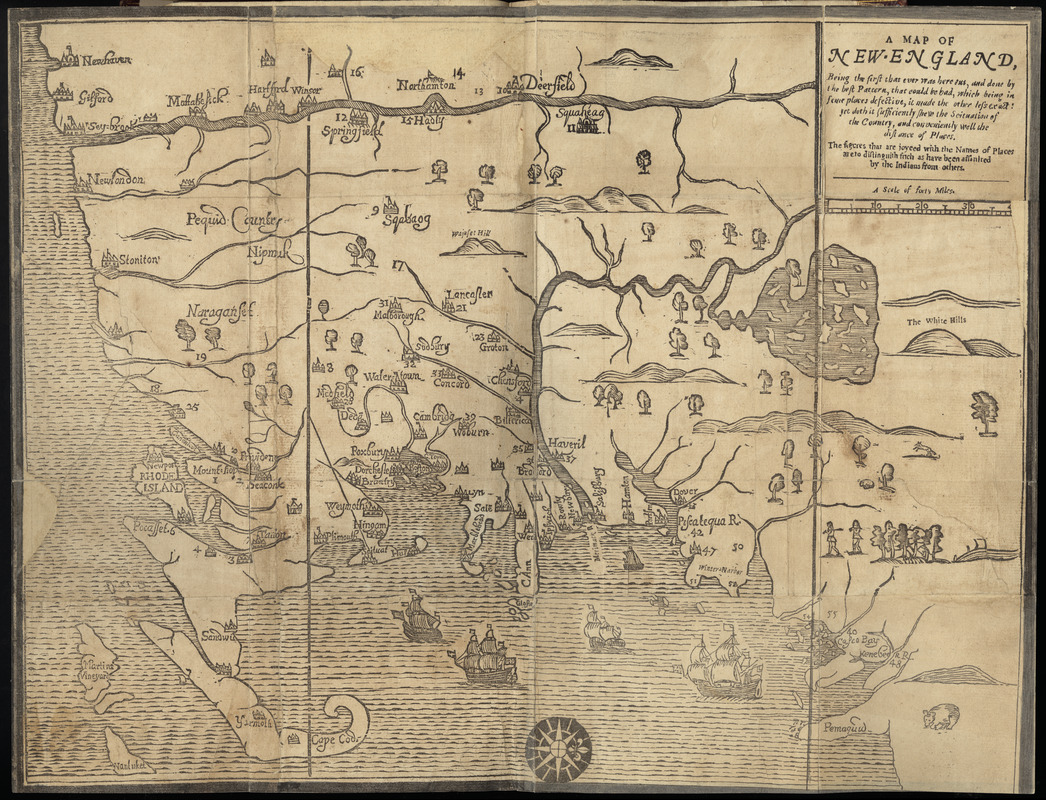

John Foster.

A Map of New-England, Being the First That Ever Was Here Cut…

1677

Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library –Rare Books Department

This map was the first to be printed in the British Colonies, and though crude in appearance was for its time the best available map of the region. Based on a 1665 survey by Bostonian William Reed, it was repurposed by Foster to illustrate William Hubbard’s Narrative of the Troubles with the Indians in New England. The Narrative described King Philip’s War of 1675-76, a horrific conflict between New England colonists and Algonquin Indians. By war’s end the native population had been decimated and dozens of colonial towns (shown numbered on this map) ravaged.

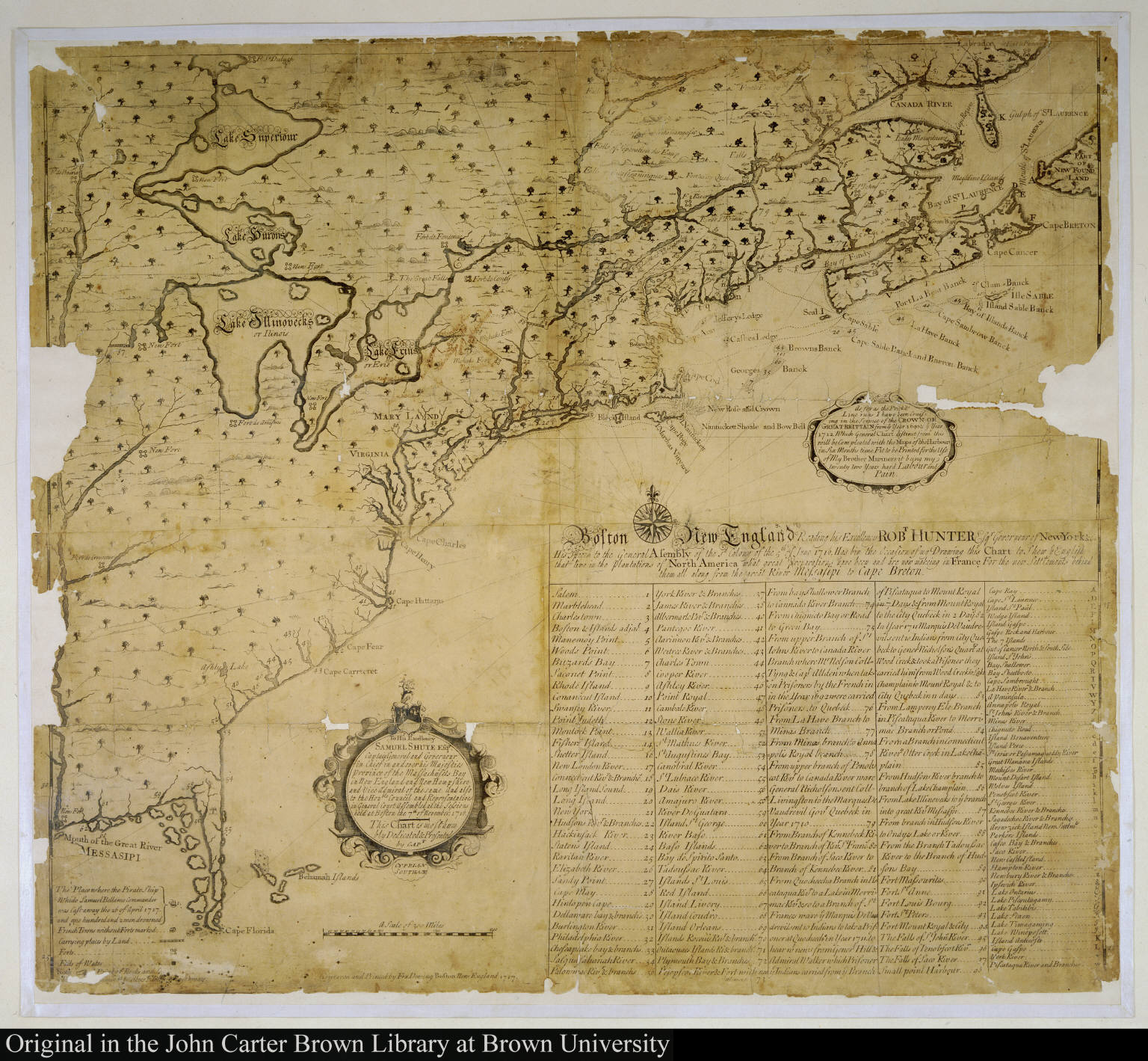

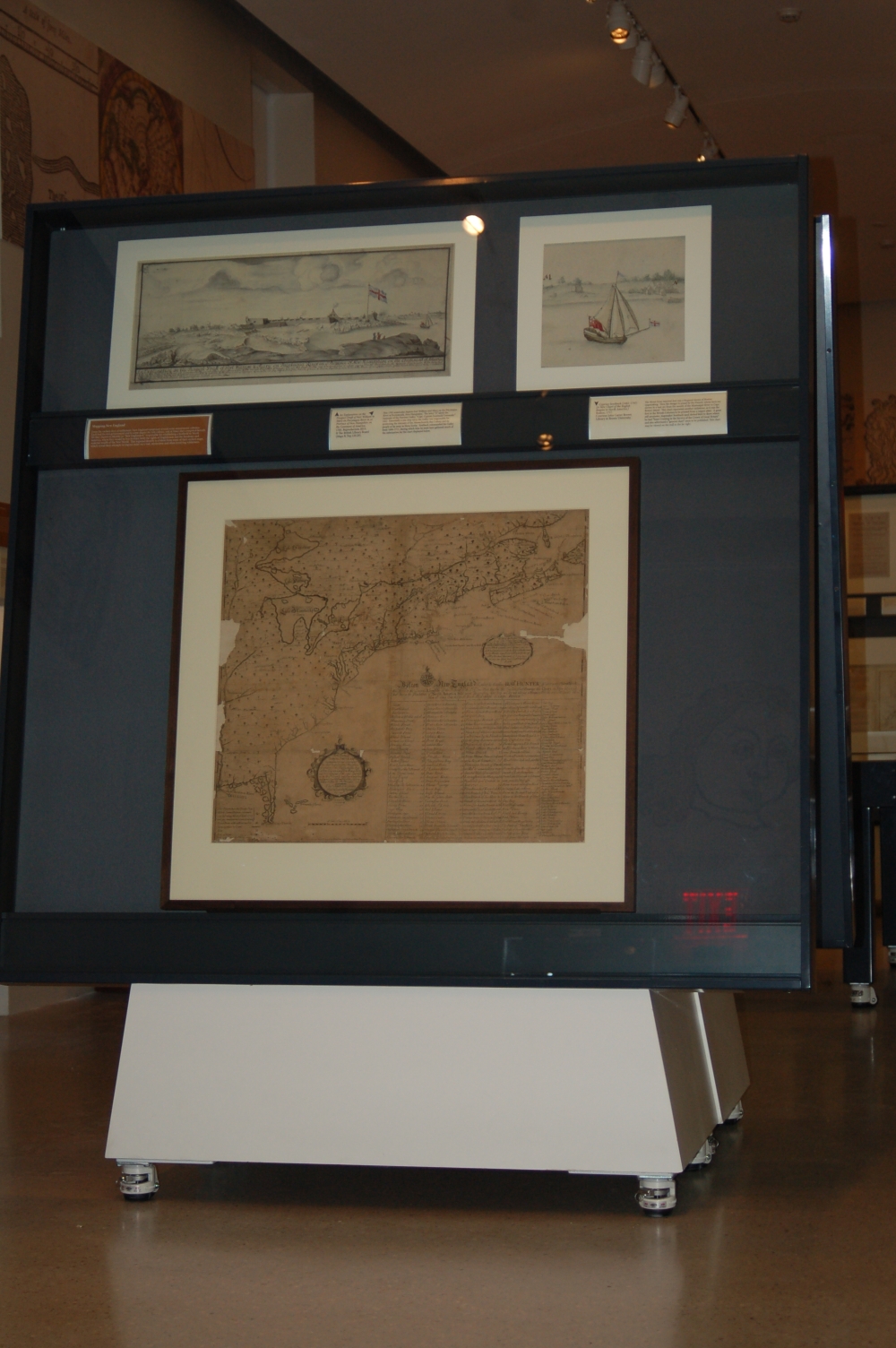

Cyprian Southack.

[A New Chart of the English Empire in North America]

1717

Courtesy John Carter Brown Library at Brown University

The threat from external foes was a frequent theme of Boston mapmaking. Here the danger is posed by the French, whose forts are shown in a vast arc from the mouth of the Mississippi River to Cape Breton Island. This map represents another milestone, as it was the first in the British Colonies to be printed from a copper plate. A great self-promoter, mapmaker Southack used dotted lines to show where he had “been Cruising in the Service of the Crown of Great Britain” and also advertised a “general chart” soon to be published.

Fort William & Mary on Piscataqua River in the Province of New Hampshire on the Continent of America

1705

© The British Library Board (Maps K.Top.120.29)

This 1705 watercolor depicts Fort William and Mary on the Piscataqua River at Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The letter “S” labels the topmasts of the Province Galley, “Capt. Cyprian Southack Comander” [sic]. Essentially a one-ship navy, the Galley was responsible for protecting the interests of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and its people as far away as Nova Scotia. Southack commanded the Galley from 1696-1711, during which time he must have gathered much of the information for his chart of New England.

William Douglass.

This Plan of the British Dominions of New England in North America, Composed from Actual Surveys

[1755]

Courtesy Library of Congress Map and Geography Division

A Scottish physician who arrived in Boston in 1718, Douglass drew this map by combining hundreds of local surveys with observations from his own “perambulations.” It outlines township boundaries and treats river systems in detail, both firsts for a map of New England. Such a detailed map could only have been produced by a resident with strong personal connections throughout the region and the ability to dig through local records. Douglass intended to distribute it free of charge to every town depicted but died before publication. It was instead engraved in London and published by his executors.

Thomas Jefferys.

A Map of the Most Inhabited Part of New England…

1755/1759

Boston mapmaking was influential in forming Great Britain’s perception of the New England colonies. For example, though William Douglass made his map of New England for local consumption, London publisher Thomas Jefferys targeted the English market by adapting it to illustrate a larger struggle for empire. Using Douglass’ map as his primary source, Jefferys made additions based on other colonial surveys and added an inset plan of Fort Saint Frederic, a French “incroachment” on Lake Champlain. This map went through several editions and for over 50 years was the pre-eminent map of New England.

2. Mapping Boston

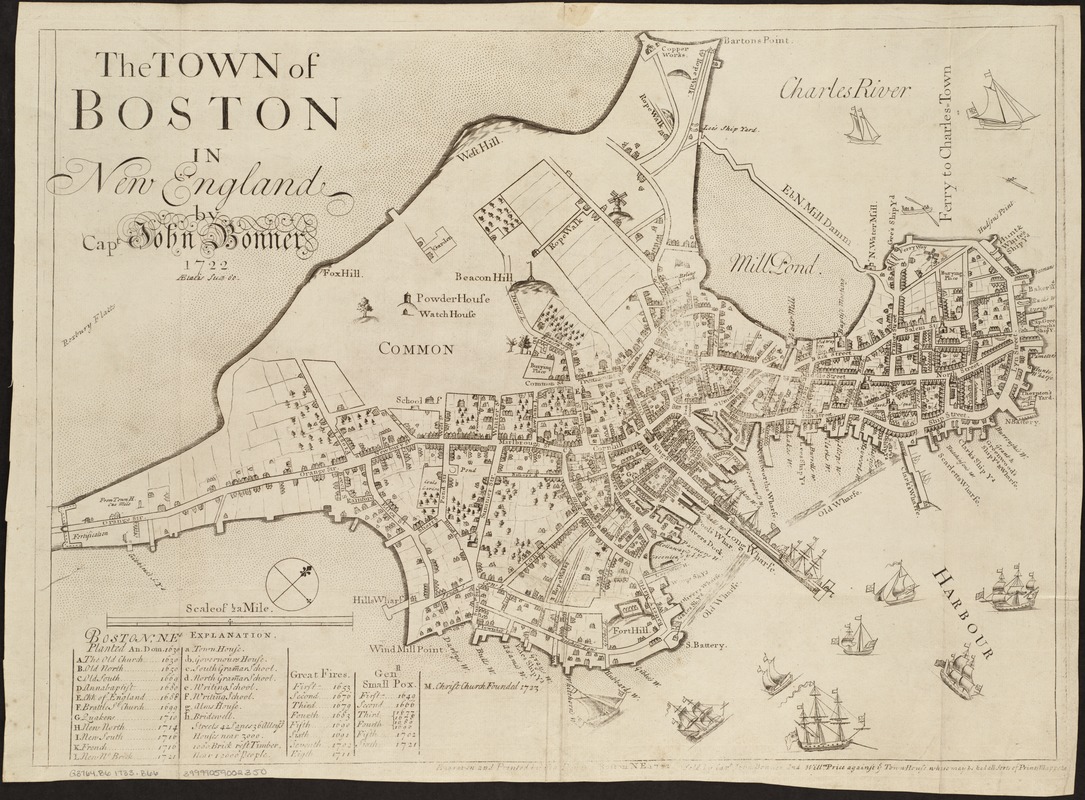

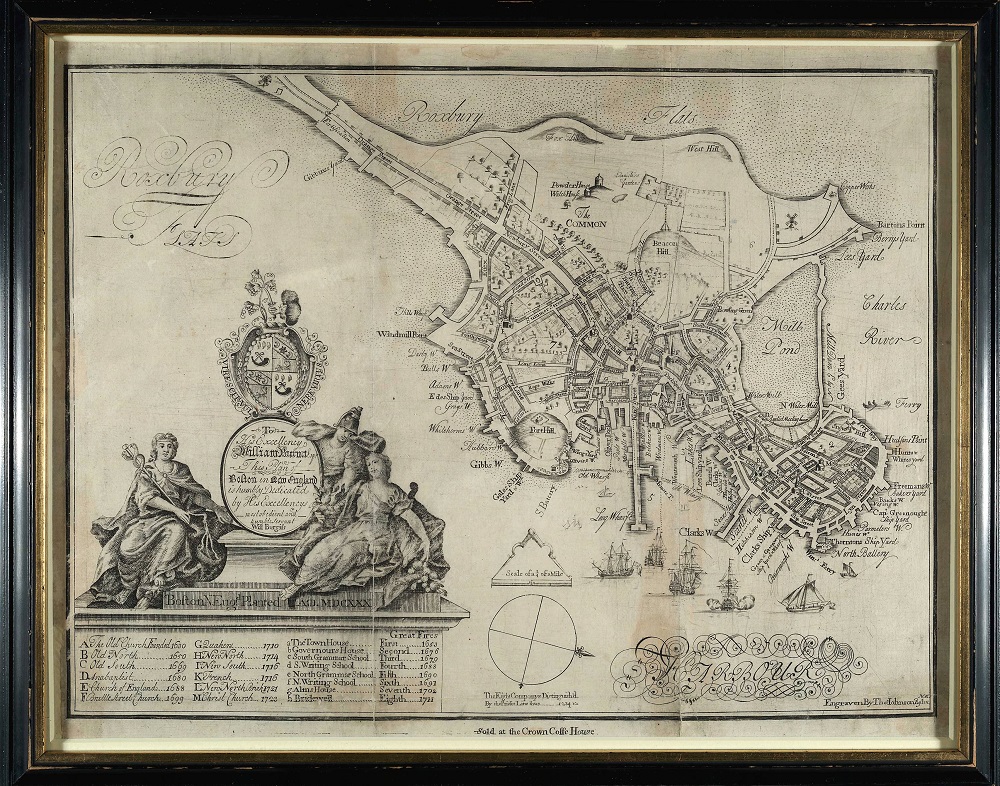

John Bonner.

The Town of Boston in New England

[1725-1728]

Bonner’s map depicts Boston before centuries of landfill transformed its coastline. His distinctive design combines plan and perspective views to convey maximum information and achieve decorative effect. It shows clearly the patterns of settlement, dense in the North End and along Cornhill and King Streets but thinning toward the south and west. The abundance of wharves, shipyards and ropewalks reflects Boston’s flourishing maritime economy. Captain Bonner was more comfortable drawing sailing vessels than topography: the shipping in the harbor is carefully rendered, whereas simple bumps near the Common represent the “Trimontane” that once dominated the town.

William Burgis.

… Boston N. Engd. Planted A.D. MDCXXX

[1728]

Courtesy Boston Athenaeum

William Burgis was an English artist who arrived in Boston in 1722. He is remembered today for publishing a remarkable view of the town (on the wall to your right), another of New York, and the plan displayed here. For this plan, Burgis borrowed heavily from John Bonner, but wisely engaged Thomas Johnston, a skillful engraver. The result is artistically superior, due in part to the ornate cartouche bearing the arms of Governor Burnet. It also includes important additions, notably the use of dotted lines indicating ward boundaries. This is one of only three known examples of the plan.

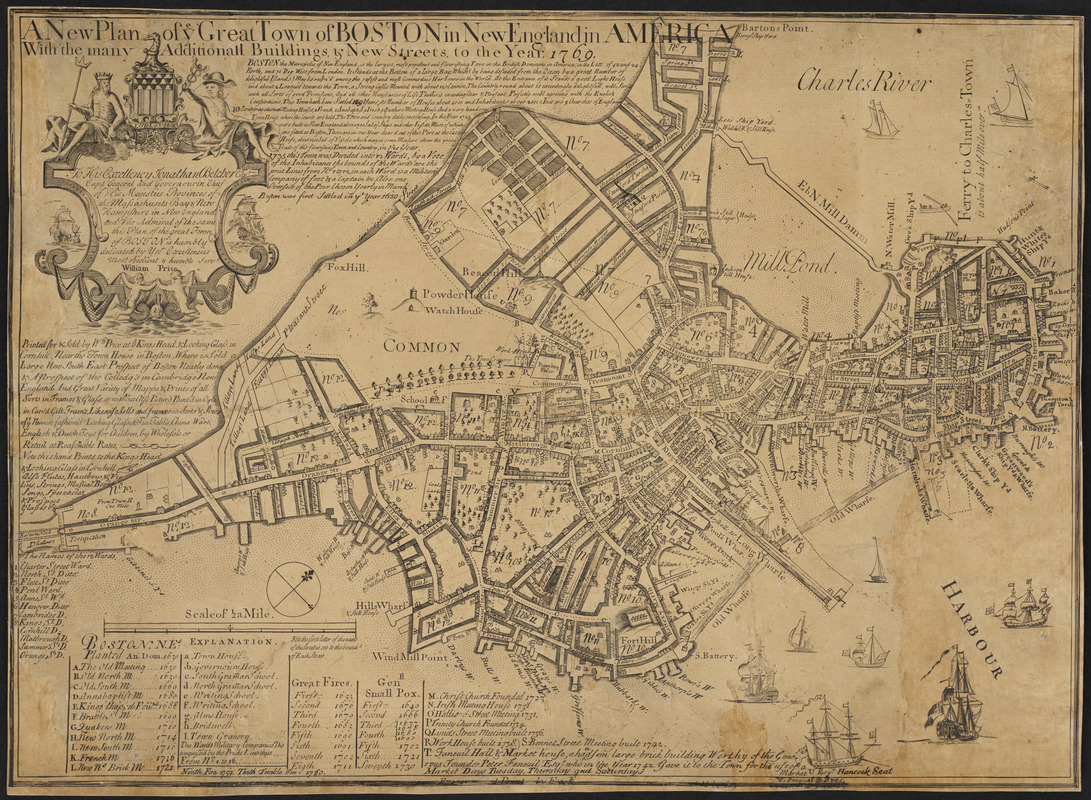

William Price.

A New Plan of Ye Great Town of Boston in New England in America

1769

After Bonner’s death in 1726, his partner William Price assumed sole ownership of the Boston plan, which he reissued several times over the next 40 years. Facing competition from Burgis’ attractive plan, Price made numerous changes, notably the addition of a decorative cartouche. He also added numerous streets in the south and west and along Boston Neck, with buildings shown by shading rather than perspective view. The re-engraving was done by Thomas Johnston, who had also engraved Burgis’ plan. The result is overcrowded and even overwhelming, but the map remains the best visual record of pre-Revolutionary Boston.

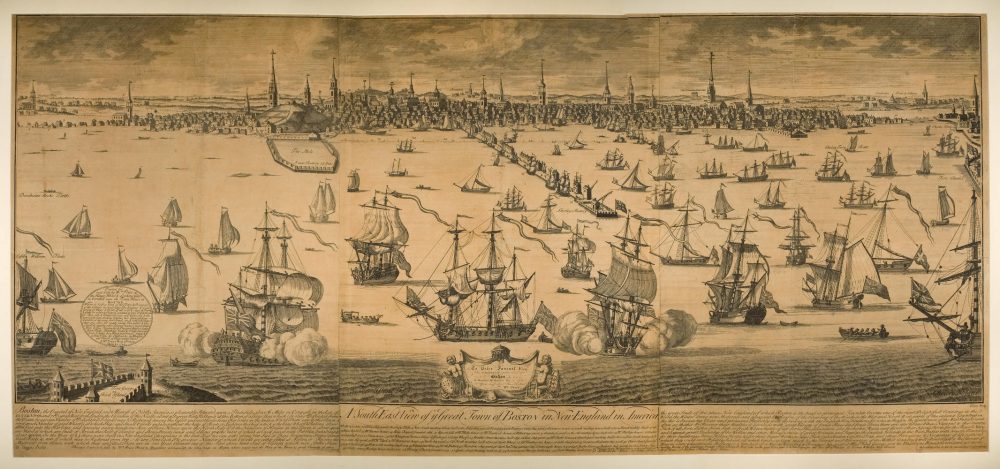

William Burgis.

A South East View of Ye Great Town of Boston in New England in America

1743

Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

This monumental view depicts Boston as seen from Castle Island, today part of the South Boston waterfront. Burgis emphasizes the town’s “capacious” harbor, “pleasant” climate, fine civic architecture, and the importance of its economy to the British Empire. The view first appeared in 1725, but displayed here is a 1743 revision. The changes include the addition of “Cambridge Town & Colleges” at upper right, though Harvard faces the wrong way and appears to “float” above the landscape. The view was originally engraved in London, but the revisions were likely made by a local engraver.

Paul Revere.

A View of Part of the Town of Boston in New-England and British Ships of War Landing Their Troops!

[1770]

Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

In 1768 the British sent regular troops to maintain order in Boston, as protests against English rule were rendering the town unmanageable. Like Burgis’ view, this engraving by Patriot Paul Revere depicts Boston from the southeast and emphasizes Long Wharf as its most striking feature. The message is however very different: Revere depicts the troops arriving as a hostile force with “cannons loaded, a Spring on their Cables, as for a regular Siege.” The view’s message was rendered all the more powerful by its publication just weeks after the Boston Massacre.

John Bonner, Capt. (1641/42-1725/26)

[ca. 1690]

Courtesy New England Historic Genealogical Society

Oil painting.

3. Cyprian Southack

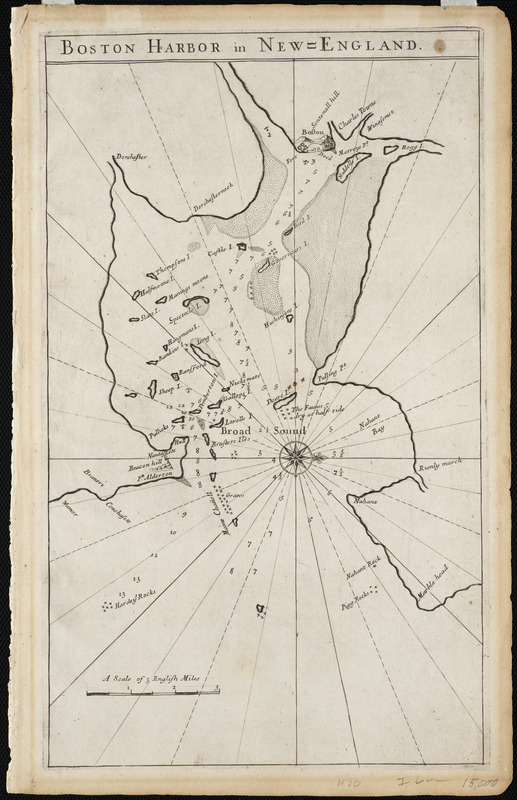

[Cyprian Southack].

Boston Harbor in New England

[1769]

Courtesy Mapping Boston Foundation

Southack’s earliest known effort was a chart of Boston Harbor, probably drawn in the late 1680s but now lost. It remains available, however, through two derivatives. This derivative is the very first printed map to focus on Boston, which appeared in The English Pilot, the first English nautical atlas. Though the cartography is crude, this chart is an important example of how the work of colonial mapmakers was circulated back in the home country.

Augustine Fitzhugh.

A Draught of Boston Harbour by Capt. Cyprian Southake

1694. Manuscript copy of original, 1884.

Southack’s earliest known effort was a chart of Boston Harbor, probably drawn in the late 1680s but now lost. It remains available, however, through two derivatives. This derivative is an 1884 copy of an ornate manuscript made in 1694 by London draughtsman Augustine Fitzhugh. Though the cartography is crude, this chart is an important example of how the work of colonial mapmakers was circulated back in the home country.

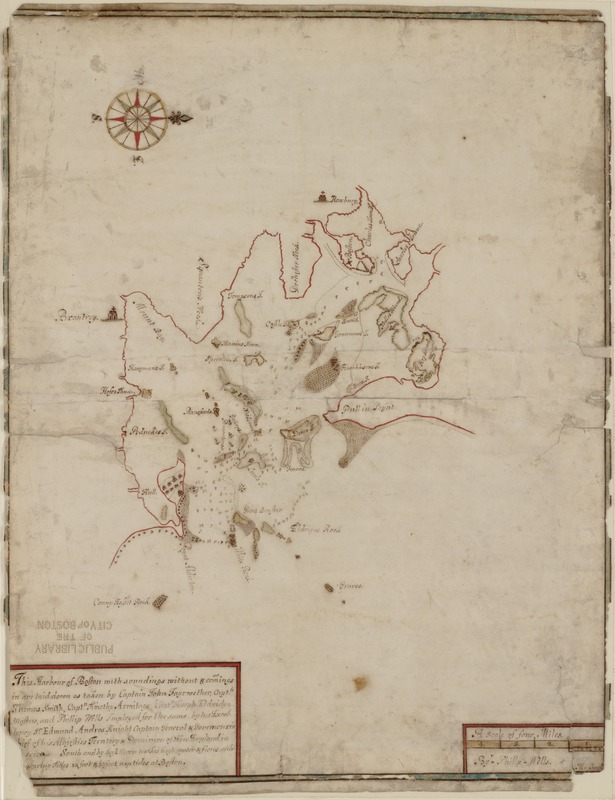

Phillip Wells.

This Harbour of Boston with Soundings Without & Comings Within…

[1686-89?]

Phillip Wells served as New York Surveyor General and was then appointed by Governor Andros to the same post in New England. Unlike Cyprian Southack’s chart, this effort compiled by Wells is impressively accurate in defining the position and shape of Boston, the major harbor islands, and the main shipping channel. The chart was found by a dealer in a group of papers of the Penn family of Pennsylvania, sold in 1871 to famed Americana collector George Brinley, and acquired thereafter by the Boston Public Library.

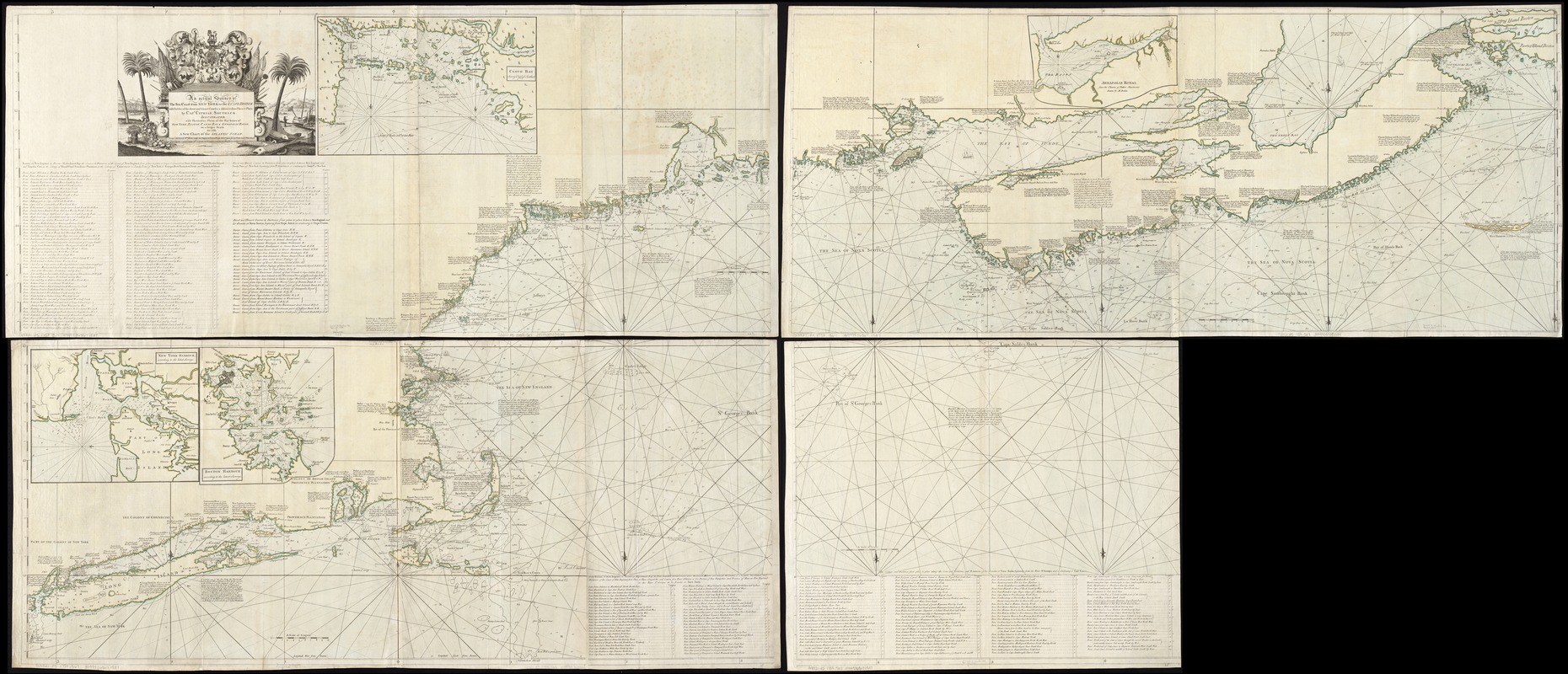

Cyprian Southack.

An Actual Survey of the Sea Coast from New York to the I. Cape Briton

[ca. 1729/1758?]

Southack first published this enormous chart in book form between 1729 and 1734 as The New England Coasting Pilot. This is a later version, with additions including inset charts of Boston Bay, Casco Bay, and New York Harbor. The chart bears many autobiographical notes, such as Southack’s 1717 voyage to Wellfleet to salvage the wreck of the pirate ship Whydah. A contemporary writer dismissed the chart as “one continued error, and … of pernicious consequence in trade and navigation.” Yet it remains a monument of colonial mapmaking, being vastly more informative than any earlier effort to map New England’s coast.

Cyprian Southack.

The Harbour of Casco Bay and Islands Adjacent

1720

For many years English settlers in coastal Maine were targets for attack by the French-backed Abenaki and other indigenous groups. Consequently, Southack made many trips to Casco Bay, including one in 1702, when as captain of the Province Galley he raised a siege of Fort Casco. During these visits he assembled an impressive body of knowledge reflected in the detailed geography and soundings on this chart.

4. Contest for Empire

Eighteenth-century North America was the scene of a global struggle for empire between France, Great Britain, Spain, and the tens of thousands of Native Americans who had survived the depredations and plagues of the 17th century. Bostonians were deeply involved in this conflict, fighting the French and their native allies as far afield as New York, Maine, Nova Scotia and the St. Lawrence. Displayed here are several maps reflecting Boston’s role in King George’s War (1744-48) and the French and Indian War (1754-1763).

Richard Gridley.

A Plan of the City and Fortress of Louisbourg with a Small Plan of the Harbour

1746

Courtesy Massachusetts Historical Society

The massive French fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island controlled access to Canada and provided a base for raiding the northern British colonies. It was thus a great triumph for New England when in June 1745 it was besieged and captured by an expedition organized by Massachusetts Governor William Shirley. Portraitist Peter Pelham (1697-1751) engraved this exquisite plan drawn by fellow Bostonian Richard Gridley, who had commanded artillery at the siege. The print is an example of how Pelham, Thomas Johnston, James Turner and other Boston engravers supplemented their income by applying their talents to mapmaking.

Thomas Johnston

A Chart of Canada River

1746

After the conquest of Louisburg, Governor Shirley began organizing an attack on Quebec. During the preparations, this chart of the St. Lawrence River was engraved by Johnston, a “Boston house painter, japanner, engraver, painter of coats of arms, church singer, publisher of singing-books and pioneer New England builder of organs.” The chart notes French settlements and provides some hydrographic data, all based on an unidentified “French draft.” Given how little was known about the area, it was fortunate that the expedition was cancelled, perhaps due to British concerns that another military success might encourage the colonies to pursue a more independent course.

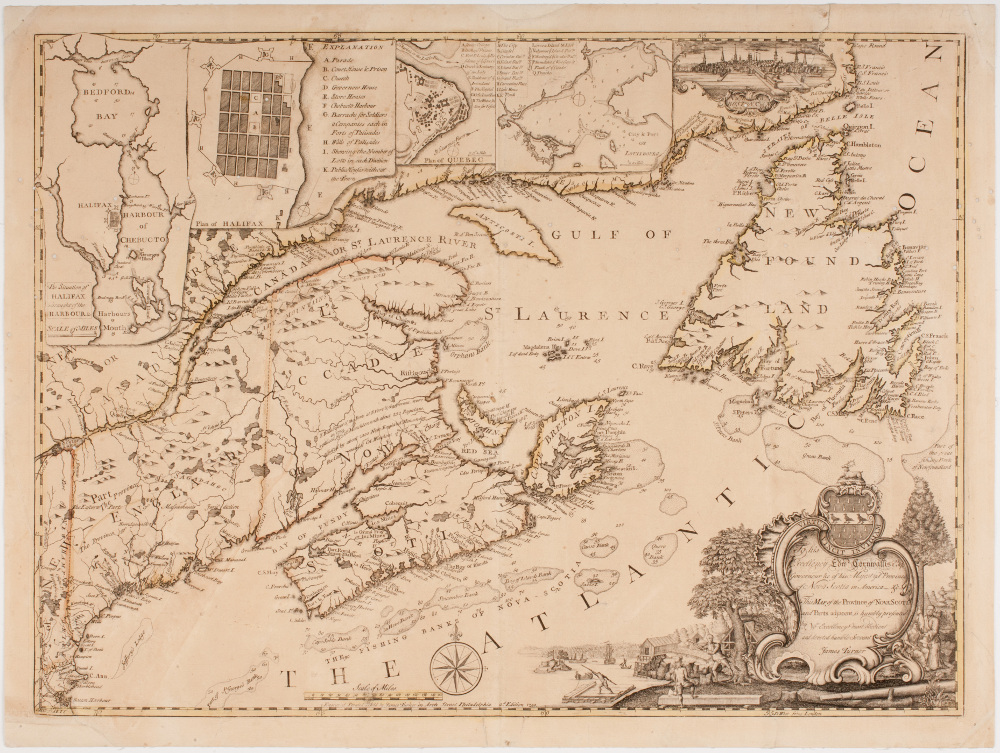

James Turner.

This Map of the Coasts of Nova-Scotia and Parts Adjacent …

[1750]

Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

This map documents the founding of Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1749. The new settlement was intended to counter French Louisbourg and became the main British naval base in North America. Most Boston maps of the colonial era were highly original creations, presenting new and detailed information available only to those “on the ground.” Here, however, Turner produced a composite from maps that had originally appeared in the Gentleman’s Magazine, published in London. He also introduced a tiny view of Boston, highlighting the connection between its security and that of Halifax.

Samuel Blodget.

A Prospective Plan of the Battle Fought Near Lake George on the 8th of September 1755 …

[1755]

Courtesy Massachusetts Historical Society

In late summer 1755, a force of colonial militia advanced up the Hudson River with the goal of capturing the French fortress of Saint Frederic on Lake Champlain. Near Lake George they were ambushed by a large force of French and Indians and suffered terrible losses. The enemy was eventually forced to retreat, allowing the colonials to claim victory even though they abandoned the campaign against Fort Saint Frederic. This remarkable plan was drawn by Samuel Blodget of Haverhill, Massachsuetts, who probably served as a sutler (supplier of food and other necessities) to the militia.

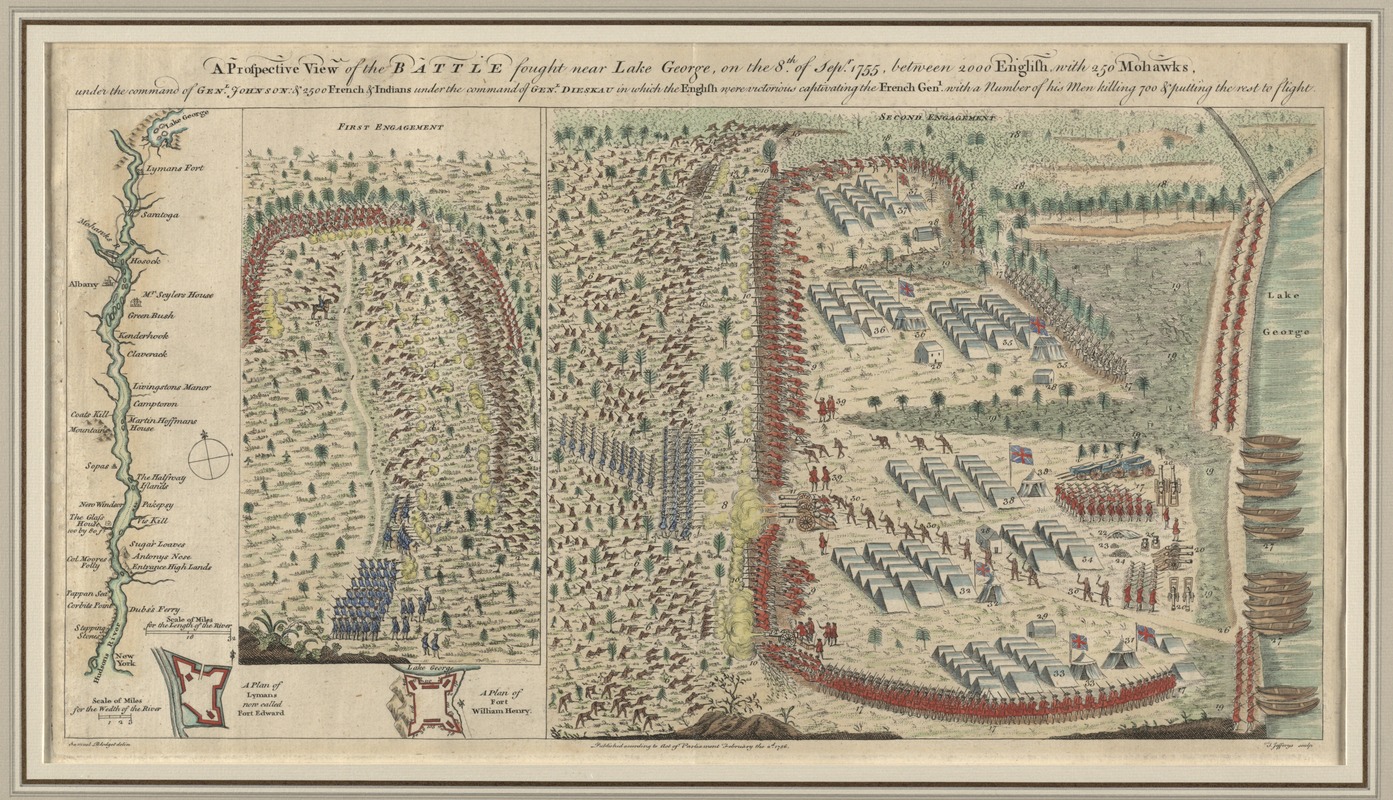

Samuel Blodget.

A Prospective View of the Battle Fought Near Lake George on the 8th of Septr. 1755

1756

Courtesy Richard H. Brown

This unusual plan of the Battle of Lake George was published in London by Thomas Jefferys just months after the events depicted. It is based closely on a plan of similar title engraved in Boston by Thomas Johnston. Cartographic plagiarism was rampant during this era, and though Blodget is credited in the lower-left margin, it is not clear whether Jefferys had obtained his permission to republish the plan. Unlike almost all known examples, this one is remarkable for displaying original color.

Timothy Clement.

This Plan of Hudsons Rivr: from Albany to Fort Edward

1756

Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

Surveyor Timothy Clement was also present at the Battle of Lake George, and produced this plan based on papers captured from the French commander supplemented by his own surveys. Like Blodget, Clement used both insets and a blend of plan and bird’s-eye views; but, being a more sophisticated map maker, drew his version to scale. Both residents of Haverhill, the two men must have been well acquainted; it would be interesting to know Blodget’s reaction upon learning that his fellow townsman had produced a competing plan and gone so far as to employ the same engraver, Thomas Johnston.

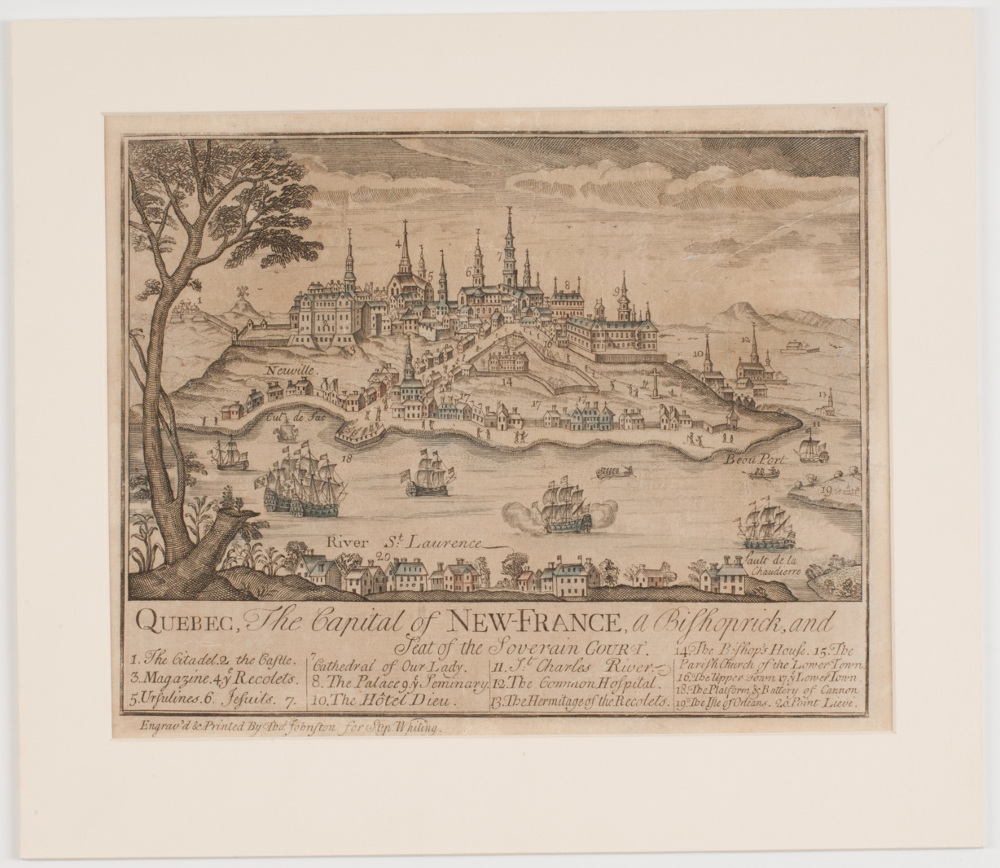

Thomas Johnston.

Quebec, The Capital of New-France, a Bishoprick, and Seat of the Soverain Court

[1759]

Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

Johnston advertised this print in August 1759, while General Wolfe was besieging Quebec and Bostonians were eager for news. The view is taken from Point Levi, across the St. Lawrence River from the city and the site of a British artillery battery. The Île d’Orléans, where Wolfe had his headquarters, can be seen at far right, while the site of the decisive British victory on the Plains of Abraham is out of view to the left. Johnston presented his engraving as fresh and “newsy,” but it was copied from a view that had appeared on a French map in 1718.

5. Contest for Land

Carelessly written land grants, primitive surveying instruments and methods, and sheer greed all contributed to boundary disputes, both within and between Britain’s North American colonies. These provided another important subject for Boston’s mapmakers, and several of the maps produced in the town documented land controversies. Featured here are examples relating to two such disputes: one between the “Plymouth Company” and “Brunswick Proprietors” over lands along the Maine coast, and another involving claimants to land around Elizabeth, New Jersey.

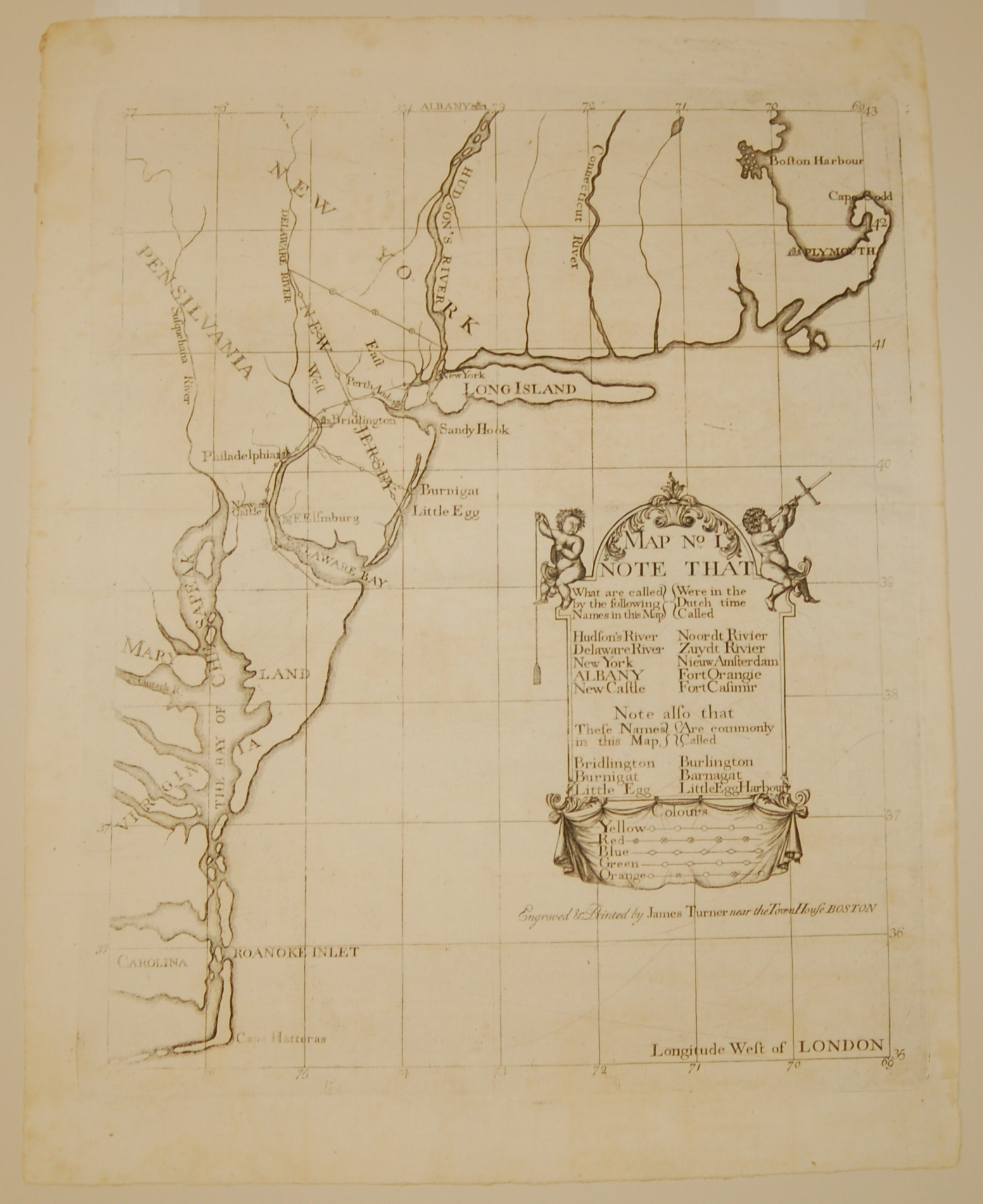

James Turner.

“Map No. I” from A Bill in the Chancery of New Jersey …

[1747]

Courtesy Dennis Gurtz

The Bill in the Chancery of New Jersey was filed by the Proprietors of East New Jersey to defend their position in a land dispute with settlers around Elizabeth. Displayed here is the first of the volume’s three maps, which provides geographical context for the early grants and charters relevant to the dispute. The involvement of Boston engraver James Turner is evidence of the town’s pre-eminence in the mid-18th century: when the Bill’s author James Alexander needed the maps engraved, Benjamin Franklin advised him that Philadelphia’s craftsmen were not up to the job and recommended Turner instead.

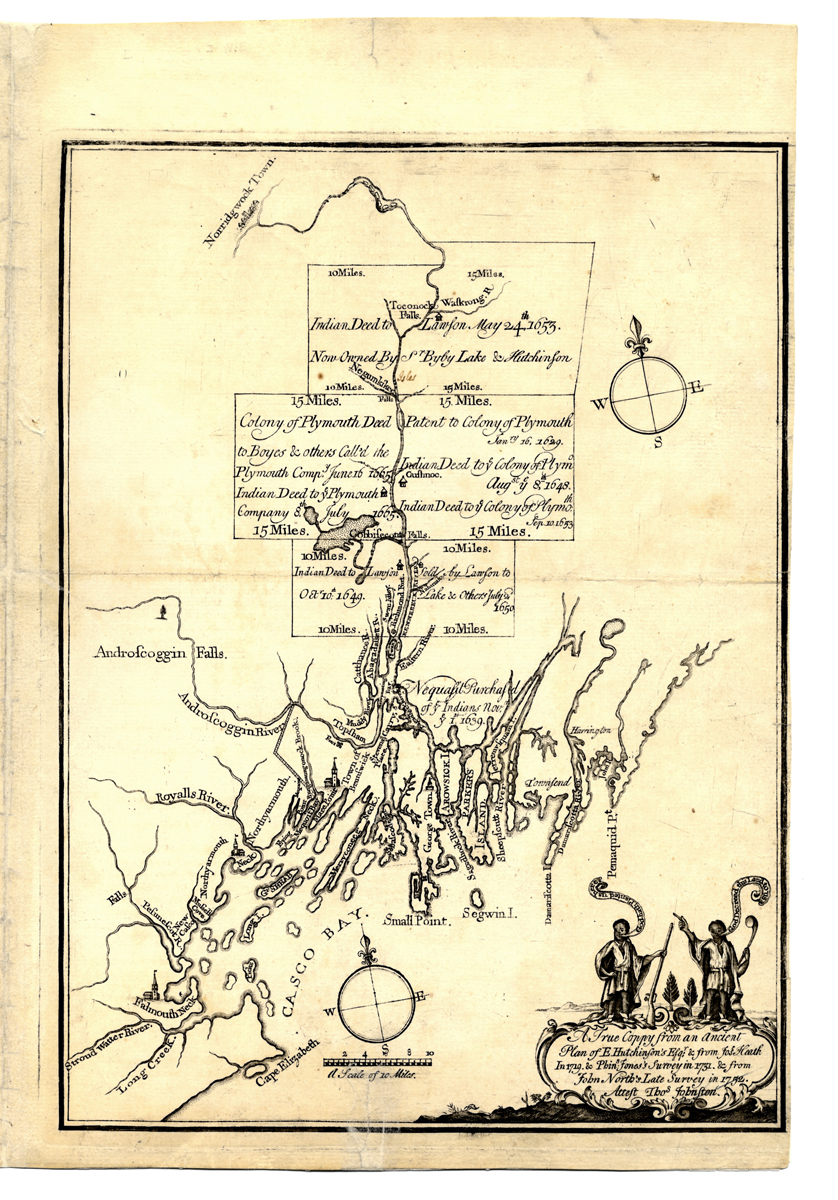

Thomas Johnston.

A True Coppy from an Ancient Plan of E. Hutchinson’s Esqgr…

[1753]

Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

This broadside was published by the Brunswick Proprietors to defend their title to a vast area extending inland from Casco Bay. Their claim was being challenged by the Plymouth Company, which declared that its own grant along the Kennebec River extended all the way to the Bay and thereby superseded the Proprietors’ claim. The complex dispute hinged on obscure questions of place names and was not fully resolved for several decades. Note the captions above the native figures at lower right, which suggest a moral equivalence between the Brunswick Proprietors and Native Americans dispossessed of their land.

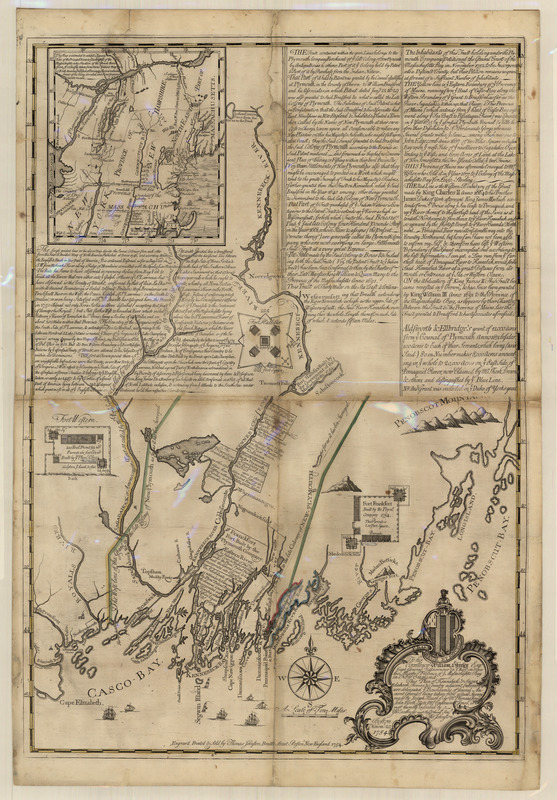

Thomas Johnston.

… This Plan of Kennebeck, & Sagadahock Rivers, & Country Adjacent …

1754

Courtesy Massachusetts Historical Society

Just a year after producing a map supporting the Brunswick Proprietors’ claim, Thomas Johnston issued this plan supporting the position of their opponents in the Plymouth Company. The map depicts the Company’s grant extending to Casco Bay and includes a long note justifying its title to the land. It also places the dispute in the broader context of Anglo-French tensions by highlighting the Company’s role in establishing Forts Franckfort and Western to protect the Maine frontier from French attacks.

Bibliography

General background

- Winsor, Justin, Memorial History of Boston…. Vol. II. The Provincial Period. Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1881. [BPL call no. F73.3 .W77 1881]

Mapping New England

- Black, Jeannette D. The Blathwayt Atlas Volume II Commentary. Providence: Brown University Press, 1975, pp. 63-72.

- Burden, Philip, The Mapping of North America II. Rickmansworth, United Kingdom: Raleigh Publications, 2007. Entry #484. [BPL call no. GA401 .B87 1996]

- Krieger, Alex and David Cobb with Amy Turner, Mapping Boston. Cambridge, Mass. and London: The MIT Press, 1999, pp. 21-116. [BPL call no. GA430 .M36 1999]

- Matthew H. Edney, “The “Percy Map”: Maps and Military Strategy during the Revolution.” Online exhibition, 1998; updated 2012. Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education, University of Southern Maine. http://www.oshermaps.org/special-map-exhibits/percy-map/.

- McCorkle, Barbara, New England in Early Printed Maps 1513 to 1800. Providence, RI: The John Carter Brown Library, 2001. [BPL call no. GA408.5.N49 M38 2001]

Mapping Boston

- Brigham, Clarence S., Paul Revere’s Engravings. New York: Atheneum, 1969, pp. 79-85. [BPL call no. NE539.R5 A57 1969]

- Cyr, Stepanie C., “A lasting impression: the discovery of a new state of the Bonner-Price maps of Boston.” June, 2008 (Unpublished article produced for the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.)

- Edes, Henry H., “The Burgis-Price View of Boston,” in Transactions, 1906-1907. Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1910. Vol. XI, pp. 245-262. [BPL call no. F61 .C711]

- Holman, Richard B. “William Burgis,” in Boston Prints and Printmakers 1670-1775. Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1973, pp. 57-81. [BPL call no. NE535.M42 B67 1973x]

- Krieger, Alex and David Cobb with Amy Turner, Mapping Boston. Cambridge, Mass. and London: The MIT Press, 1999, p. 174 and plates 24-26. [BPL call no. GA430 .M36 1999]

- Reps, John W., “Boston by Bostonians: The Printed Plans and Views of the Colonial City by its Artists, Cartographers, Engravers and Publishers,” in Boston Prints and Printmakers 1670-1775. Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, pp. 3-56. [BPL call no. NE535.M42 B67 1973x]

- Stokes, I.N. Phelps, and Daniel G. Haskell, American Historical Prints, Early Views of American Cities, Etc., from the Phelps Stokes and other Collections. New York: New York Public Library, 1933, entry 1722 – B-51 and plate 11-a entry C. 1722 – B-53 and plate 10-b, entry 1768 – B-102 and plate 21-a. [BPL call no. NE954.2 .N39 1933x]

- Winsor, Justin, Memorial History of Boston…. Vol. II. The Provincial Period. Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1881, pp. xlix-lv. [BPL call no. F73.3 .W77 1881]

Cyprian Southack

- Brinley, George, Catalogue of the American Library of the Late Mr. George Brinley… Fifth Part. Boston: C.F. Libbie & Co., 1893, p. 144 (lot #9316).

- Burden, Philip, The Mapping of North America II. Rickmansworth, United Kingdom: Raleigh Publications, 2007. Entry #666. [BPL call no. GA401 .B87 1996]

- Chard, Donald F., “Southack, Cyprian,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 3, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed August 27, 2013, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/southack_cyprian_3E.html.

- Hitchings, Sinclair, “Guarding the New England Coast: The Naval Career of Cyprian Southack,” in Seafaring in Colonial Massachusetts. Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1980, pp. 43-65. [BPL call no. F61 .C71 vol. 52]

- Krieger, Alex and David Cobb with Amy Turner, Mapping Boston. Cambridge, Mass. and London: The MIT Press, 1999, p. 98 and plate 15. [BPL call no. GA430 .M36 1999]

- LeGear, Clara Egli “The New England Coasting Pilot of Cyprian Southack,” in Imago Mundi, vol. XI (1954), pp. 137-144. [BPL call no. GA1 .I6]

- Tapley, Harriet, The Province Galley of Massachusetts Bay, 1694-1716. Salem, Mass: The Essex Institute, 1922. (Reprinted from The Historical Collections of the Essex Institute, vol. LVIII. Also available on line at http://archive.org/stream/provincegalleym00taplgoog#page/n8/mode/2up.)

- Winsor, Justin, Memorial History of Boston…. Vol. II. The Provincial Period. Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1881, pp. xlix-lv. [BPL call no. F73.3 .W77 1881]

Contest for Empire

- Anderson, Fred, Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766. New York: Vintage Books, 2000. [BPL call no. E199 .A59 2000]

- Borneman, Walter R. The French and Indian War. New York: Harper Perennial, 2006. [BPL call no. E199 .B67 2006]

- Browne, George Waldo. Hon. Samuel Blodget: The Pioneer of Progress in the Merrimack Valley. Manchester, N.H., 1907.

- Fales, Martha G., “James Turner, Silversmith-Engraver,” in Georgia Brady Barnhill, ed., Prints of New England. Worcester, Mass: American Antiquarian Society, 1991, pp. 1-20. [BPL call no. NE510 .P74 1991x]

- Hitchings, Sinclair, “Thomas Johnston,” in Boston Prints and Printmakers: 1670-1775. Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, pp. 83-132. [BPL call no. NE535.M42 B67 1973x]

- Howe, Fisher, “Notes on the Clement-Johnston Map of Lake George 1756.” Typescript held by the American Antiquarian Society, 1931.

- Howe, Fisher, ALS to Horace Brown, Esq. New York, NY: May 1931. Typescript held by the American Antiquarian Society.

- Oliver, Andrew, “Peter Pelham (c. 1697-1751) Sometime Printmaker of Boston,” in Boston Prints and Printmakers: 1670-1775. Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, pp. 133-173. [BPL call no. NE535.M42 B67 1973x]

- [Sargent, George Henry?], “The Bibliographer,” in Boston Evening Transcript, No. 231 (Oct. 1, 1913), p. 25. [BPL call no. AN2 .M4B6872]

- Stokes, I.N. Phelps, and Daniel G. Haskell, American Historical Prints, Early Views of American Cities, Etc., from the Phelps Stokes and other Collections. New York: New York Public Library, 1933, entry 1755 – C-13 and plate 16, entry P. 1758 – B-17. [BPL call no. NE954.2 .N39 1933x]

Contest for Land

- Edney, Matthew, “Competition over Land, Competition over Empire: Public Discourse and Printed Maps of the Kennebec River, 1753-1775,” in Martin Bruckner, Early American Cartographies. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, pp. 276-305.

- Fales, Martha G., “James Turner, Silversmith-Engraver,” in Georgia Brady Barnhill, ed., Prints of New England. Worcester, Mass: American Antiquarian Society, 1991, pp. 1-20. [BPL call no. NE510 .P74 1991x]

- Hitchings, Sinclair, “Thomas Johnston,” in Boston Prints and Printmakers: 1670-1775. Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, pp. 83-132. [BPL call no. NE535.M42 B67 1973x]

- Miller, George J., “The Printing of the Elizabethtown Bill in Chancery” in Pamphlet Series No. 1: Addresses before the Board of Proprietors of the Eastern Division of New Jersey. Perth Amboy, NJ: George J. Miller, pp. 3-20.

- Wroth, Lawrence, “The Thomas Johnston Maps of Kennebec Purchase,” in In Tribute to Fred Anthoensen, Master Printer. Portland, ME: Anthoensen Press, 1952, pp. 77-107.

Exhibitions and other catalogues

- Burden, Philip, The Mapping of North America II. Rickmansworth, United Kingdom: Raleigh Publications, 2007. [BPL call no. GA401 .B87 1996]

- Grolier Club, Catalogue of an Exhibition of Early American Engraving Upon Copper: 1727-1850. New York: Grolier Club, 1908.

- Hitchings, Sinclair, “A New England Album,” in Archives of American Art Journal. Washington, D.C., 1971. Vol. 9 no. 4, pp. 17-26. [BPL call no. N11.A735 A15]

- McCorkle, Barbara, New England in Early Printed Maps 1513 to 1800. Providence, RI: The John Carter Brown Library, 2001. [BPL call no. GA408.5.N49 M38 2001]

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, A Descriptive Catalogue of an Exhibition of Early Engraving in America, December 12, 1904-February 5, 1905. Cambridge, Mass: University Press, 1904. [BPL call no. NE506 .B6]

- Shadwell, Wendy, American Printmaking: The First 150 Years. City of Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1969. [BPL call no. NE505 .M8x]

- Stauffer, David. American Engravers on Copper and Steel. New York: The Grolier Club of New York, 1907.

- Worcester Art Museum and The American Antiquarian Society, Art in New England: Early New England Printmakers. Worcester: Worcester Art Museum, 1939 (Also available on line at http://archive.org/stream/artinnewenglande00worc#page/n3/mode/2up.)

- Worms, Laurence and Ashley Baynton-Williams, British Map Engravers. London: Rare Book Society, 2011.

- Wroth, Lawrence C. and Marion W. Adams, American Woodcuts and Engravings, 1670-1800. Providence: The Associates of the John Carter Brown Library, 1946. [BPL call no. NE505 .W7 1946x]

Credits

Michael L. Buehler

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center Staff

Lauren Chen, Cataloger

Alison Cody, Development and Program Manager

Stephanie Cyr, Assistant Curator of Maps

Ronald Grim, Curator of Maps

Michelle LeBlanc, Director of Education

Janet Spitz, Executive Director

Evan Thornberry, Reference and

Preservation Librarian

Catherine Wood, Office Manager

Graphic Design and Production

Framing and Matting

Andrew Leonard

Digital and Web Services

Tom Blake

Bahadir Kavlakli

Lenders to the Exhibition

Boston Public Library Rare Books Dept.

Richard H. Brown

Paul DeCoste

Dennis Gurtz

Massachusetts Historical Society

New England Historic Genealogical Society

Support generously provided by:

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps, Inc.

Boston Rare Maps, Inc.

Cohen & Taliaferro LLC

High Ridge Books, Inc.

MapRecord Publications

Martayan Lan & Augustyn, Inc.

The Old Print Shop, Inc.

Press

Museums & Galleries: Map Quest

The Improper Bostonian, February 19-March 4, 2014, p. 76

War Put Boston on the Map

Wall Street Journal, January 21, 2014

Made in Boston

Back Bay Sun, January 14, 2014

Boston-area to do list: Made in Boston

Boston Globe, November 19, 2013