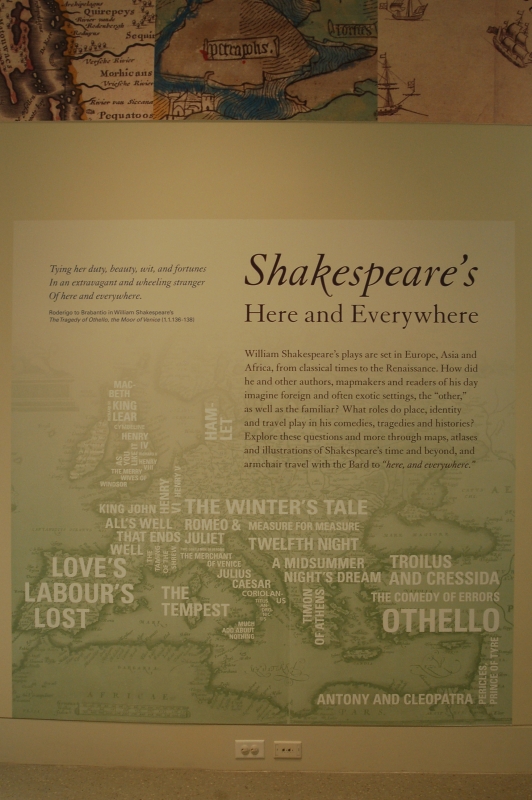

Introduction

Tying her duty, beauty, wit, and fortunes

In an extravagant and wheeling stranger

Of here and everywhere.

– Roderigo to Brabantio in William Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice (1.1.136-138)

William Shakespeare’s plays are set in Europe, Asia and Africa, from

classical times to the Renaissance. How did he and other authors,

mapmakers and readers of his day imagine foreign and often exotic

settings, the “other” as well as the familiar? What roles do place,

identity and travel play in his comedies, tragedies and histories?

Explore these questions and more through maps, atlases and illustrations

of Shakespeare’s time and beyond, and armchair travel with the Bard to

“here, and everywhere.”

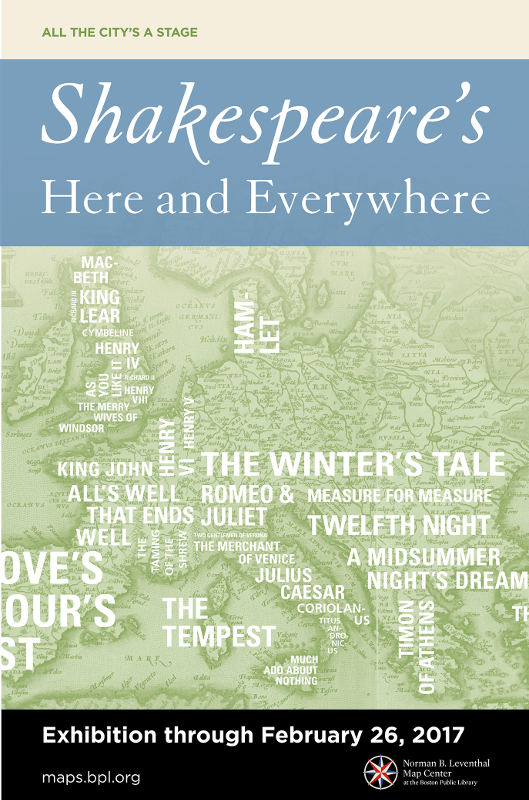

1. The World in the Time of Shakespeare

Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598)

“Typus Orbis Terrarum,” from Theatrum Orbis Terrarum

Antwerp, 1570. Reproduction, 2016.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

In 1570 Dutch mapmaker Abraham Ortelius, a contemporary of William Shakespeare, published a revolutionary item – a book of maps illustrating the entire known world. Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, or “Theater of the World,” was the first modern world atlas, and was wildly popular throughout Europe during its forty years in production. The Theatrum reader was introduced to the known world of the Renaissance, as experienced through the fifty-three maps in the atlas, and could travel the globe without ever having to leave home.

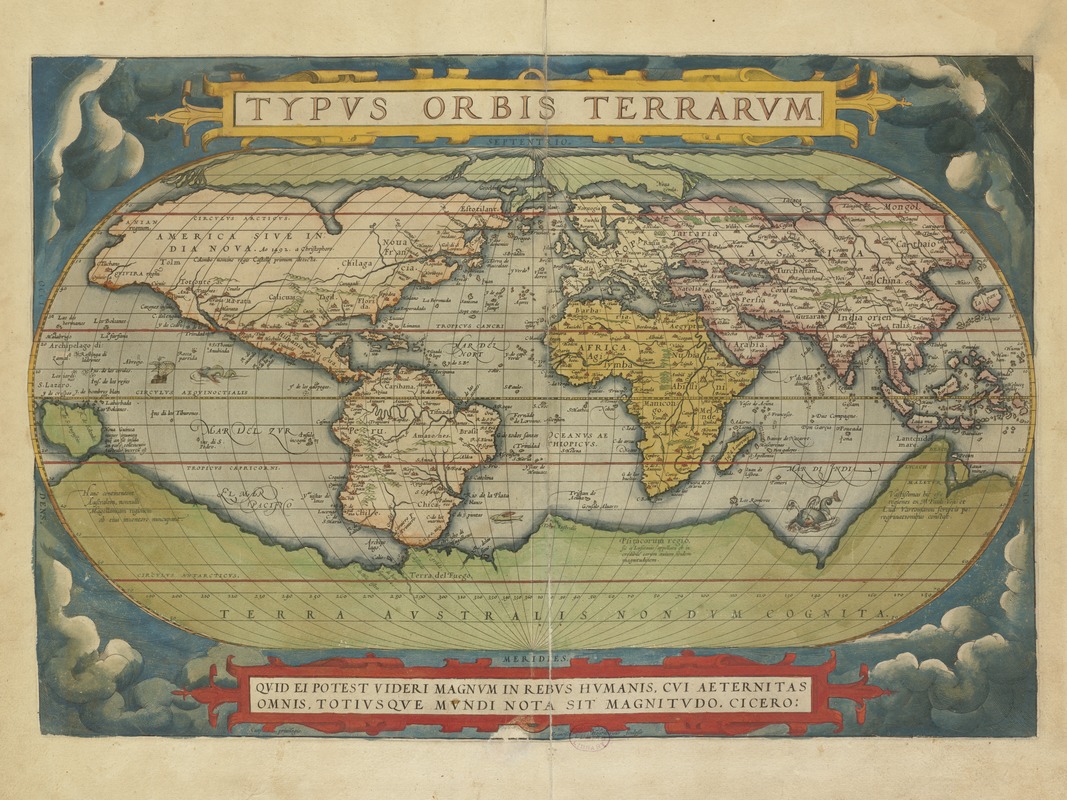

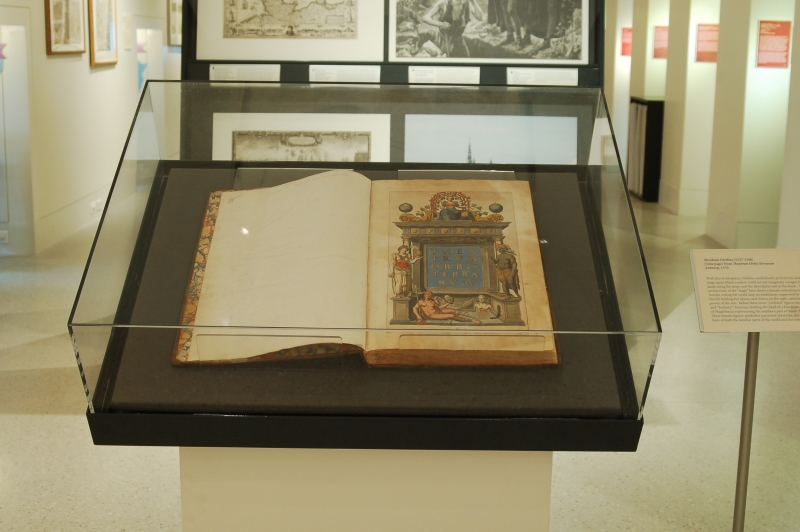

Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598)

Title page from Theatrum Orbis Terrarum

Antwerp, 1570.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

With this frontispiece, Ortelius symbolically presents his atlas as a stage upon which readers could act out imaginary voyages to distant lands using the maps and the descriptive text in the book. The architecture of the “stage” here shows a female embodiment of Europe, ruling the world atop an entablature supported by Asia on the left holding her spices, and Africa on the right, radiating with the power of the sun. Below these more “civilized” figures lies a nude and “barbaric” America, holding the head of a European, near a bust of Magellanica representing the southern part of South America. These female figures symbolize perceived identities, stereotypes and fears of both the familiar parts of the world and the unknown.

Heinrich Bünting (1545-1606)

Die Gantze Welt in ein Kleberblat

Magdeburg, Germany, 1581.

Courtesy Mapping Boston Foundation.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) lived during a time of change, discovery, and creativity. During this time, known as the Renaissance – French for “rebirth – Europeans were redefining their concept of the world, bridging from an insular medieval view to a modern global perspective. This cloverleaf-shaped map exemplifies a medieval world view, with Europe, Africa and Asia revolving around the hub of Jerusalem. Made in the late 16th century, this image reminded its viewers of biblically-focused maps, while referencing the recent discovery of America in the bottom left corner.

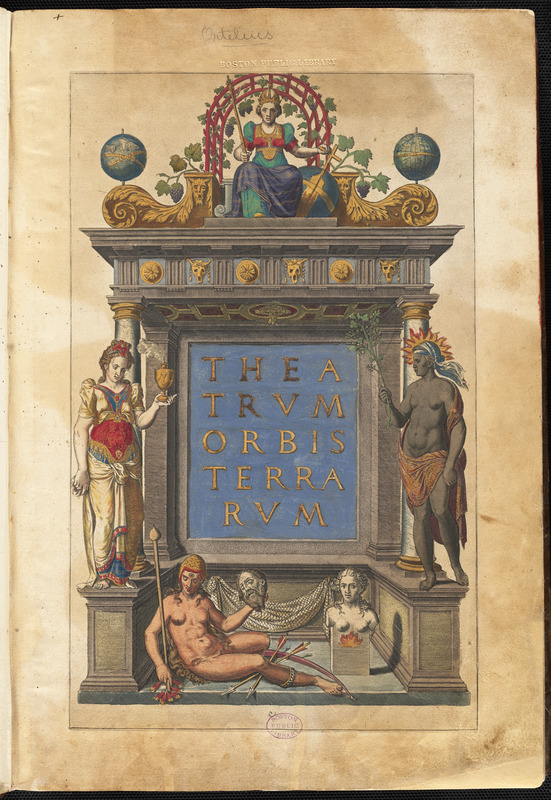

Gerard de Jode (1509-1591)

Uniuersi Orbis seu Terreni Globi in Plano Effigies

Antwerp, 1578.

Courtesy Mapping Boston Foundation.

Created during Shakespeare’s lifetime, this map illustrates the late 16th-century concept of the world. Europe and the Mediterranean regions were well understood and confidently mapped, while Africa and Asia were also mapped. The Americas are shown with recognizable east coasts, but the west coasts are based on conjecture. The unknown territories in the Americas and stories of the natives played into the fears of people in Europe. Maps of these areas display imaginative “barbarians,” “cannibals,” and dangerous alien creatures constituting a threat to “civilized” society.

Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598)

“Europae,” from Theatrum Orbis Terrarum

Antwerp, 1570. Reproduction, 2016.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

Abraham Ortelius, an older contemporary of William Shakespeare, created the groundbreaking atlas Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, including this map of Europe, the Mediterranean, Northern Africa, and Western Asia. These regions were heavily traveled for trade and known by reputation to educated people of Renaissance Europe. Many of Shakespeare’s characters traveled from their homeland to the far corners of these regions, bringing back reports of unfamiliar and exotic cultures. These “different” societies would have held a certain allure and wonder for Shakespeare’s audiences, yet at the same time implied a threat, creating an effective tension for dramatic performance.

2. Britain in the Time of Shakespeare

Robert Morden (d. 1703)

A New Mapp of England Scotland and Ireland

London, [1687]

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

The Elizabethan Age was one that strived for regulation and obedience, but was marked by religious tension and political turmoil. Britain was ruled by Queen Elizabeth I from 1558 to 1603, with King James I succeeding her. This map illustrates late 17th-century Britain, some seventy years after Shakespeare’s death, and indicates the numerous cities, towns and roads of the time. A royal family tree details each successor to the throne after William the Conqueror. In his history plays, Shakespeare dramatized the reigns of Kings John, Richard II, Richard III, Henry V, and others who appear on this family tree, as well as that of Henry VIII, a collaborative work with John Fletcher.

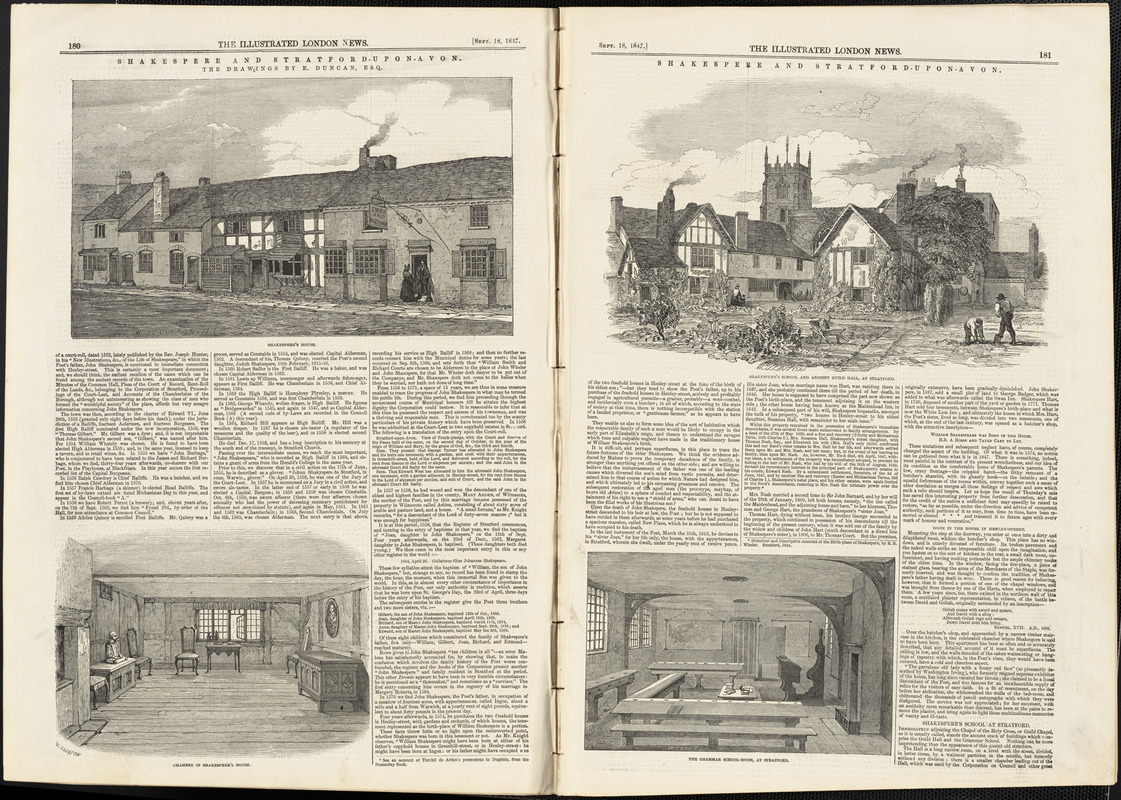

3. Shakespeare's Birthplace

E. (Edward) Duncan, Esq. (1803-1882)

“Shakespeare and Stratford-upon-Avon,” from The Illustrated London News

London, 1847 September 18.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

William Shakespeare is believed to have been born on April 23, 1564, in the town of Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, some 100 miles from London. His father John was a glove maker and eventually Mayor of Stratford, and his mother Mary was the daughter of a prosperous farmer. The 19th-century images displayed here illustrate the house where William was born, the grammar school he attended, and other places of interest in Stratford. Shakespeare’s career took him to London by 1592, while his wife Anne Hathaway and their three children remained in Stratford. Shakespeare returned to his hometown during the summers, retired there after 1613, and died there in 1616.

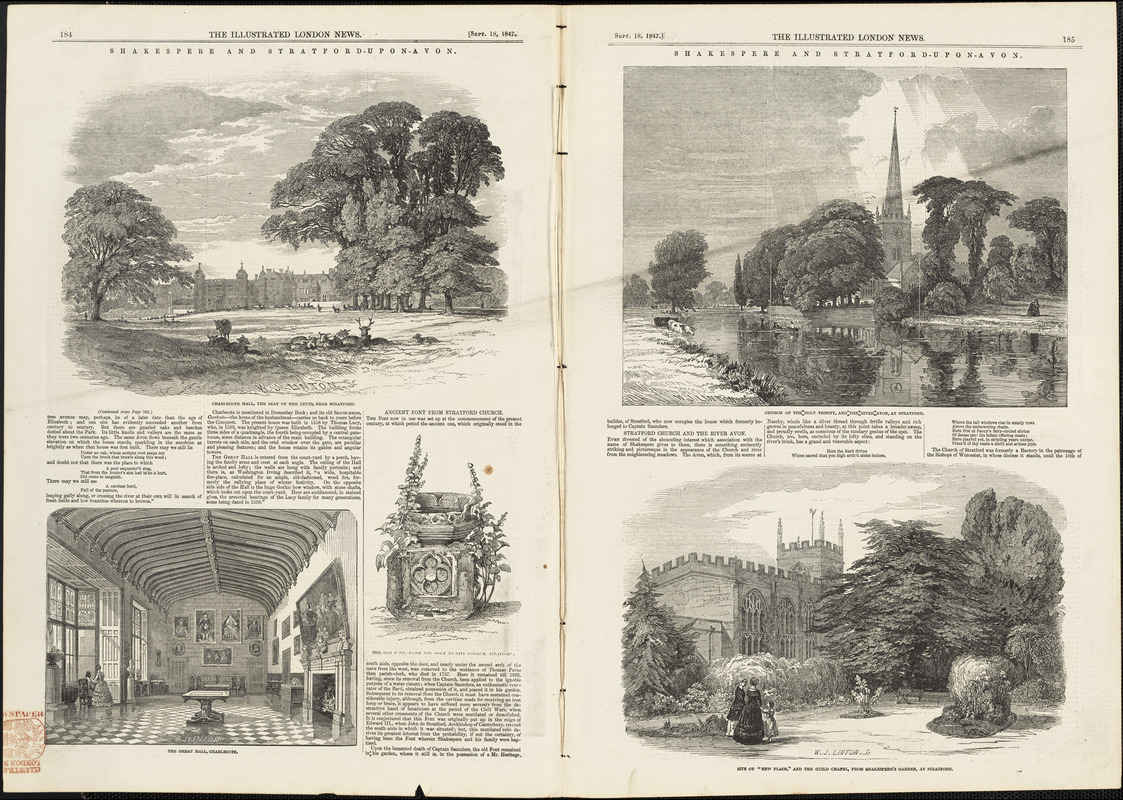

W. Hemings (active 19th cent.)

Plan of Shakespeare’s Birth-Place

[London], 1824.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

William Shakespeare was born into a middle-class family in Elizabethan England, and grew up in a comfortable home on Henley Street in Stratford-upon-Avon. The early 19th-century house plan displayed here shows what Shakespeare’s boyhood home looked like in 1824 – 260 years after his birth – along with neighboring properties and their owners. On the first floor there are a number of rooms in which to prepare food, such as a kitchen, pantry and buttery. These utilitarian rooms were separated from the living quarters, which were on the second floor. The glove shop run by Shakespeare’s father John was in the adjoining property.

Harper & Brothers

Views of London in 1616 and 1890

New York, 1890. Reproduction, 2016.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

The arts were flourishing in Britain when Shakespeare worked and wrote in London. He was a member of the acting company the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, later upon the accession of James I called the King’s Men, which by law was allowed to perform for the public only because of its patron sponsorship.

This 1890 panoramic view compares 1616 and 1890 scenes of London and shows the Globe Theater. Shakespeare was a part owner of the playhouse along with his fellow actors. Opened in 1599, the Globe was destroyed by a fire in 1613, rebuilt, and endured until 1642, when it was closed in response to Puritanical laws forbidding the performance of plays.

J. Nichols (Publisher)

“The Bear Garden; The Globe Theatre,” from Gentleman’s Magazine

London, 1816 February.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

Published two centuries after his death, this small print depicts Shakespeare’s round, open-air Globe Theater situated on the Southwark side of the Thames River, as well as a neighboring arena, The Bear Garden.

Abraham Ortelius’ atlas entitled “Theater of the World” provided maps as stage settings for global events. William Shakespeare’s theater, aptly named the Globe, was a venue for human imagination and performance not bound by geographic borders or distances.

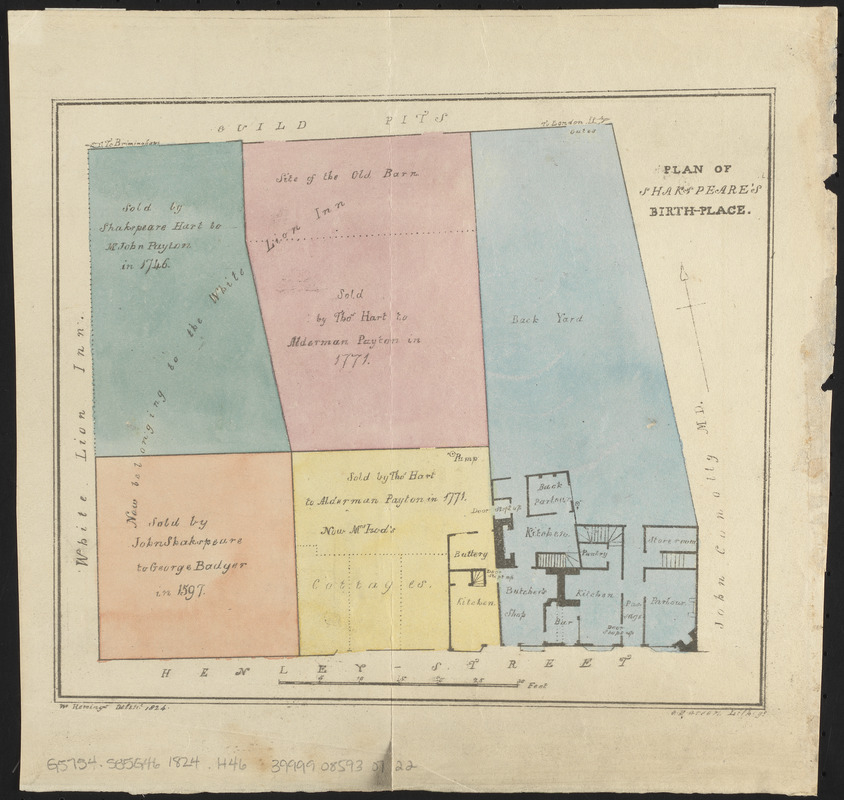

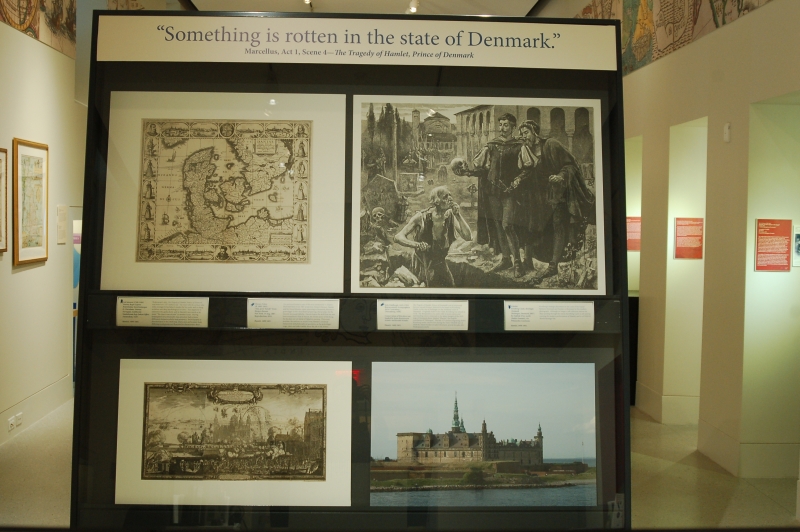

4. Northern Europe

“Something is rotten in the state of Denmark.”

-(Marcellus, Act 1 Scene 4 - Hamlet)

Jan Jansson (1588-1664)

Daniae Regni Typum Potentissimo Invictissimoque D. Christiano, Daniae, Norvegiae, Gotthorum Vandalorum Regi Lubens Offert

Amsterdam, 1629.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

Hamlet, 1600-1601.

Shakespeare’s play, The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, was based on a 12th-century tale. The story tells of a prince who seeks revenge for his father’s murder by his uncle, and in doing so delves into deep psychological territory. This negativity is echoed in Marcellus’ line “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark,” and in Hamlet’s own words as he states “The time is out of joint” in 1.5.188. During Shakespeare’s era, Denmark’s class structure had extreme differences between nobility and peasantry. Such disparity is demonstrated in this 1629 map, where men and women from differing social groups are illustrated in characteristic dress.

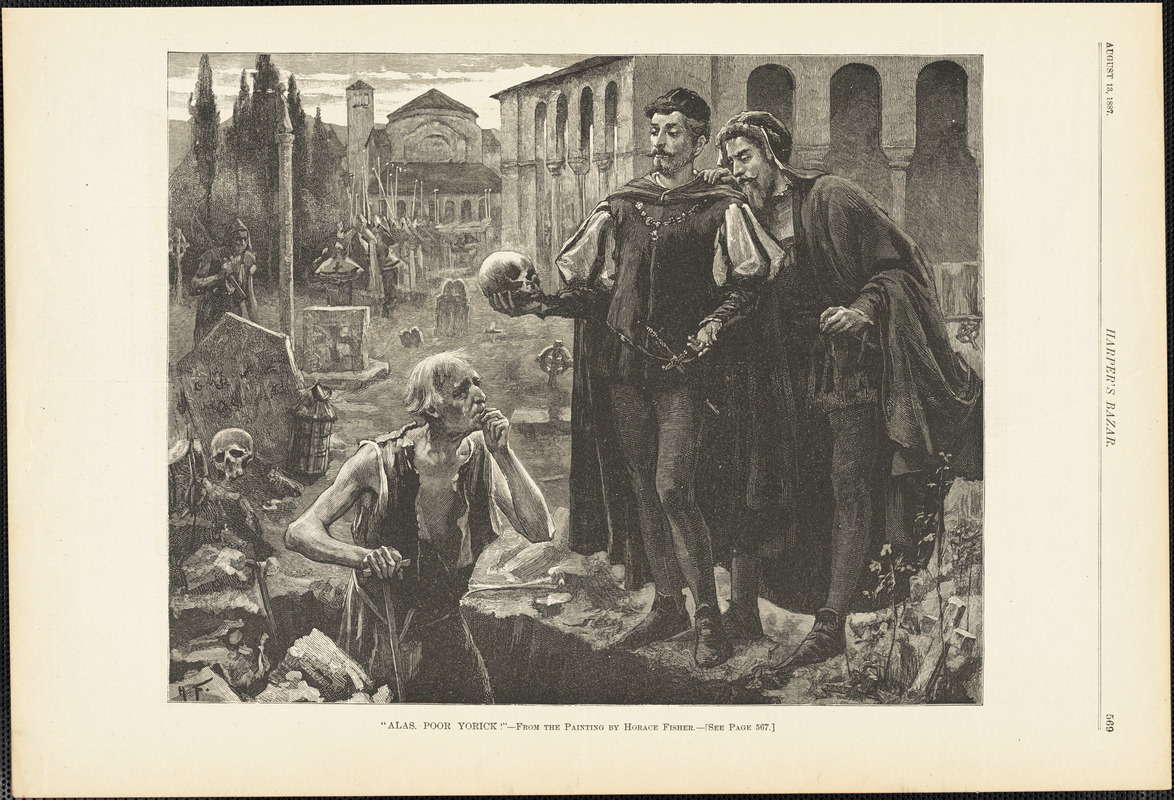

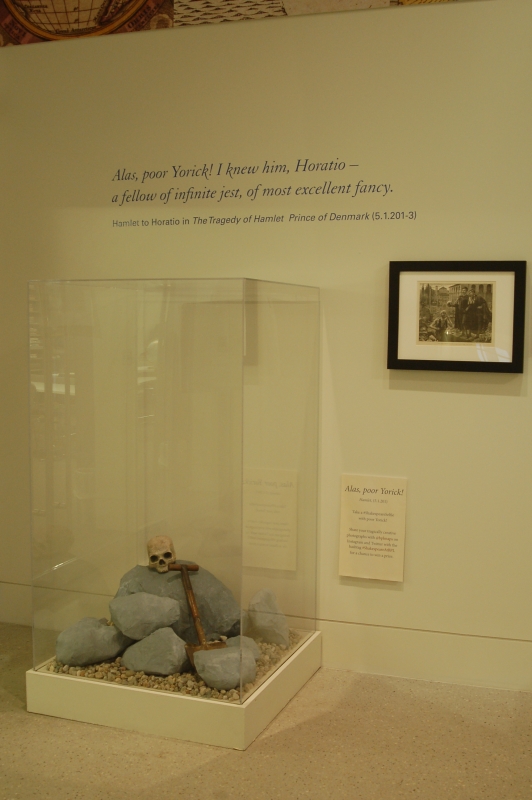

Horace Fisher (fl. 1882-1893)

“Alas, poor Yorick!” from Harper’s Bazaar

New York, 13 Aug. 1887. Reproduction, 2016.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

Hamlet, 1600-1601.

The graveyard scene is one of the most memorable in Hamlet. Illustrated here in an 1887 print from Harper’s Bazaar, Hamlet, upon returning to Denmark, and his friend Horatio discover a gravedigger in the churchyard preparing a burial place for the recently deceased Ophelia. Hamlet learns the skull that has just been unearthed is that of Yorick, the former jester of the King, but he does not yet know of Ophelia’s passing. This scene provides the audience with more than a respite from Hamlet’s continual melancholy and philosophical questions, as the gravedigger sings, jokes and talks frankly to the Prince about his job.

Erik Dahlbergh (1625-1703)

Repraesentatio Scenographica Arcis Cronenburg …

[Nuremberg, 1696]

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

Conservation of this piece was funded by Anna Kuznetsova-Schafer and Ronald Schafer.

Hamlet, 1600-1601.

The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark is set in a fictional fortress named Elsinore, believed to be based on Kronborg Castle, and its environs in the city of Helsingør on the northeast coast of Denmark. Originally built in the 1420s, Kronborg was rebuilt in 1574. The Renaissance-era castle with its iconic spires and surrounding town is depicted in the upper margin of the 1629 map of Denmark, labeled “Elsenor,” the English translation of “Helsingør.” The late 17th-century engraving shows Kronborg under cannon fire during the Dano-Swedish war of 1658-60, when Sweden invaded Denmark, several decades after Shakespeare’s death.

Fiskfisk

Kronborg Castle, Helsingør, Denmark

[Helsingør, Denmark, 2007]

By Fiskfisk (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Hamlet, 1600-1601.

Kronborg’s strategic placement on the coast of the Sound between Denmark and Sweden is illustrated in this modern photograph. Although no longer a toll collection station for ships passing through the sound, Kronborg Castle is still used as a setting for modern performances of Hamlet, and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

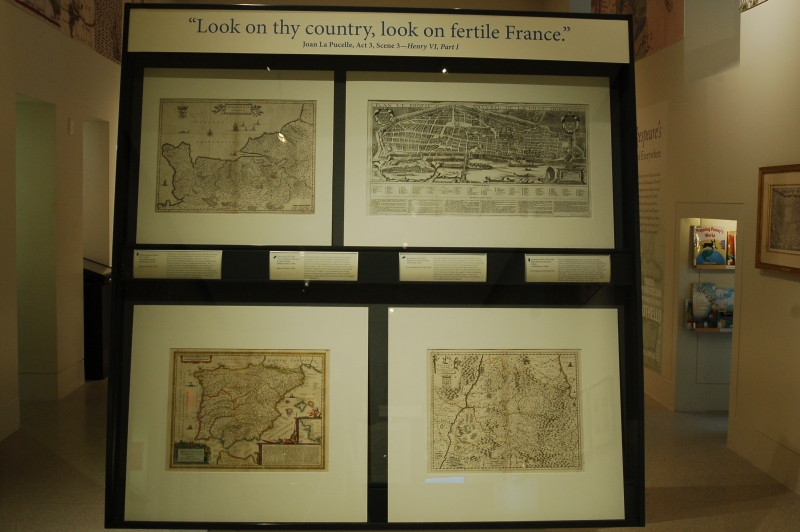

5. Western Europe

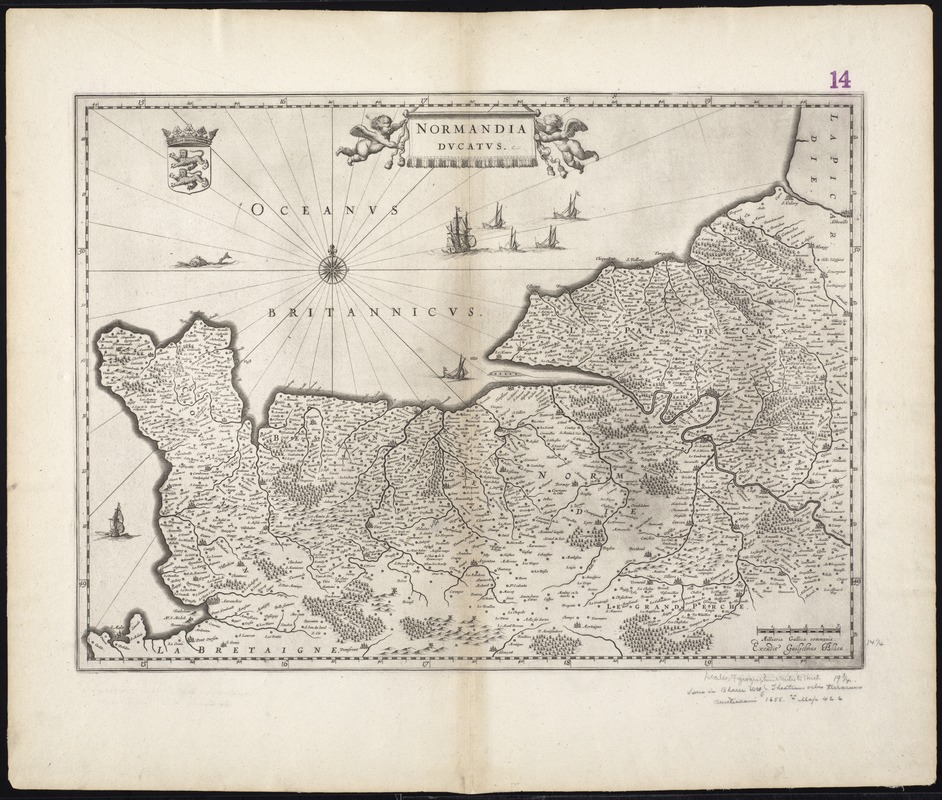

Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1571-1638)

Normandia Ducatus

[Amsterdam, 1635]

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

Henry VI, Part I, 1592.

Shakespeare wrote a number of history plays, which were based on earlier works by other authors. However, the Bard did not always follow history to the letter. In Henry VI, Part I, probably a collaborative work with several other dramatists, Shakespeare manipulates dates of actual events, as well as facts related to people, to create a greater dramatic effect. For example, the character Joan La Pucelle, based on Joan of Arc, was portrayed as an unwed mother and witch in the play, contrary to actual facts. The area near Rouen in Normandy, as illustrated in this 1635 map, was one of the settings for Henry VI, Part I, wherein Joan urged her countrymen to “Look on thy country,” and reclaim France for themselves.

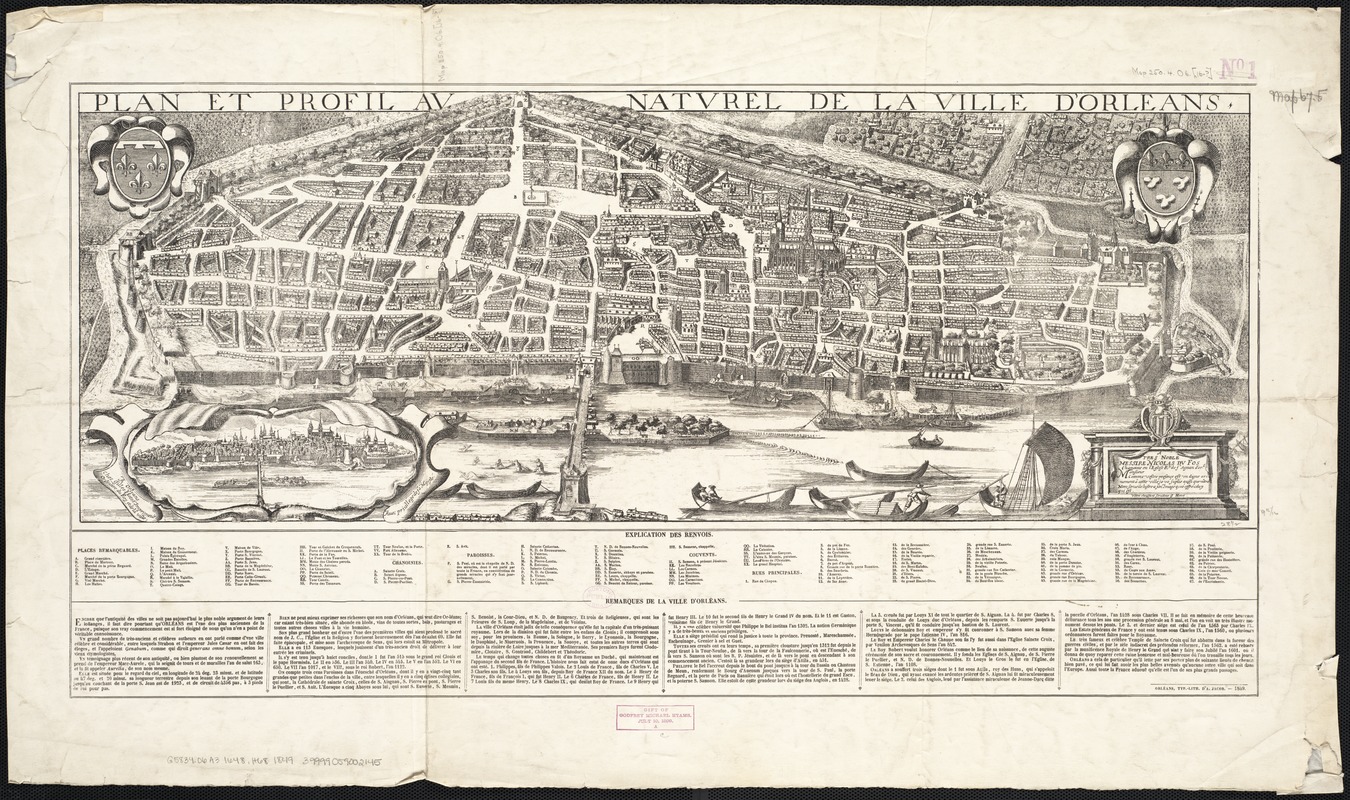

Gilles Hotot

Plan et Profil au Naturel de la Ville d’Orleans

Orléans, France, 1849.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

Henry VI, Part I, 1592.

France and England had a fractured relationship during the Renaissance, as the two sides battled regularly against one another for control of French lands. The town of Orléans, depicted in this view originally from 1648, was the site of a famous siege in 1429. It was here that young Joan of Arc (Joan La Pucelle) rallied the French army behind her, and recaptured Orléans from the English. In its villainizing of the French characters and triumph of English heroes, Henry VI, Part I supported a feeling of pride in country and monarch in England under Elizabeth I.

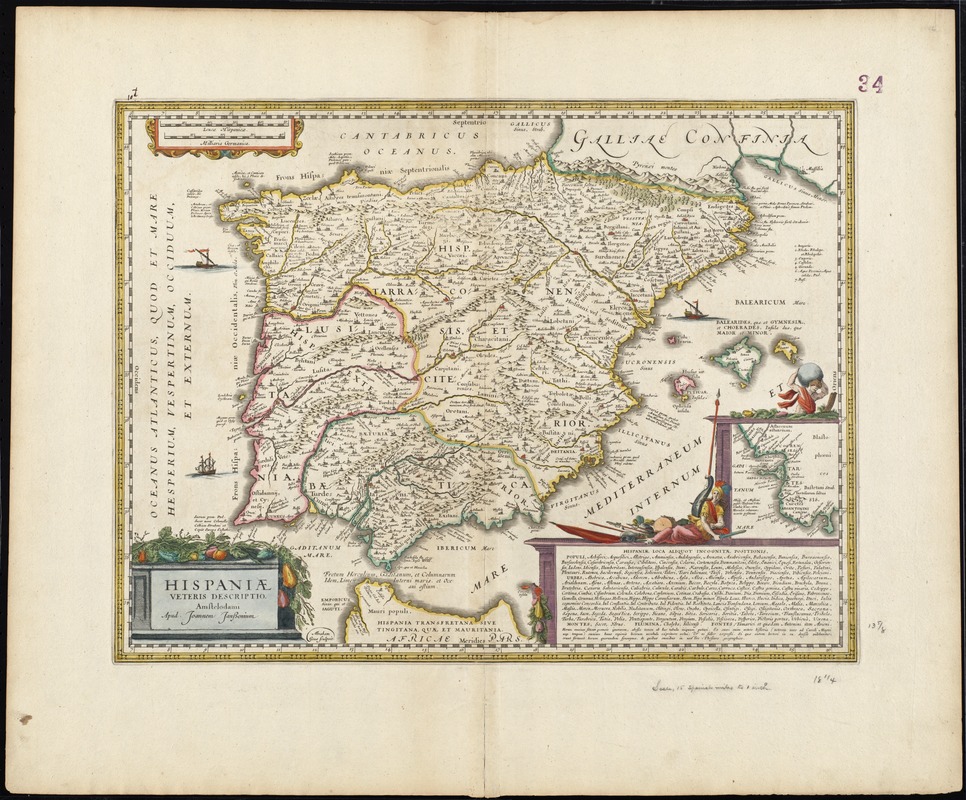

Jan Jansson (1588-1664)

Hispaniae Veteris Descriptio

Amsterdam, 1638.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

Love’s Labours Lost, 1594-1597.

Set in the kingdom of Navarre, Spain, Love’s Labour’s Lost is a romantic comedy about four young Spanish men, who, despite their best efforts to avoid romance and focus on their studies, fall in love with four French women. The play appears to be an original by Shakespeare, and may have been written for a specific, private audience in mind. As illustrated in this 1638 map, Renaissance-era Spain was a place of numerous separate kingdoms, ruled by different heads of state. Navarre and bordering France had a tenuous relationship, as did Navarre with neighboring Spanish kingdoms.

Frederick de Wit (1630-1706)

Regni Navarrae Accurata Tabula

Amsterdam, ca. 1680.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

Love’s Labours Lost, 1594-1597.

Today, the self-governing province of Navarre, located in northern Spain, borders France in a region called Basque Country. The area as it looked in the 17th century is illustrated in this map. During Shakespeare’s time, Navarre was divided into Spanish and French lands, but remained an important place as a bridge between the two countries. Henry IV was king of Navarre from 1572-89, and king of France from 1589-1610. The monarch was well regarded in matters of war, but carried a notorious reputation as a womanizer – the exact opposite to Shakespeare’s character of Ferdinand, King of Navarre, who actively tried to deny Cupid’s will.

6. Southern Europe

Herman Moll (d. 1732)

A New Map of Italy Distinguishing all the Sovereignties in it, Whether States, Kingdoms, Dutchies, Principalities, Republicks, &c …

London, 1714.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

During the Renaissance, Italy was a nation of separate city-states, regions that were either republics, loyal to a sovereign, or under the authority of the Pope in Rome. Italian culture was also transitioning from a medieval way of life, to a modern one where people could own businesses, although there remained a large gap between the aristocracy and the working-class. The map displayed here shows how Italy was divided in the early 18th century. Each of these regions had a distinct history and culture, which would have been known to Shakespeare and his contemporaries through a variety of literary and historical sources. Twelve of the Bard’s plays take place in Italy.

“What's the news from Venice?”

-(Gratiano; Act 3, scene 2 – The Merchant of Venice)

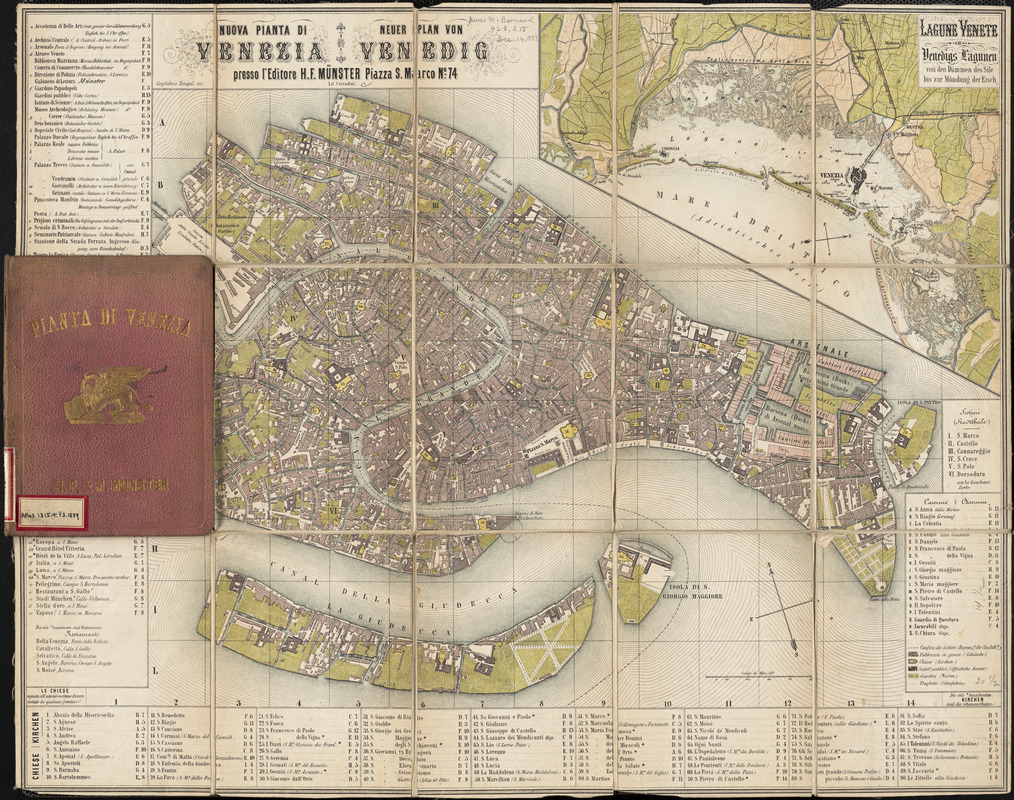

H.F. Münster (Firm)

Nuova Pianta di Venezia = Neuer Plan von Venedig

[Venice], 1859.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

The Merchant of Venice, 1596-98 and Othello, the Moor of Venice, 1601-02.

Venice was an important and powerful republic in Renaissance Italy, having long been a major player in trade and maritime activities. The city was also a melting pot, serving as a trading center between Europe and the Middle East and Asia. Two of Shakespeare’s most tormented figures have their stories unfold in Venice. Othello, a Moor and military officer, and Shylock, a Jewish moneylender, both represent the diversity, or “otherness” that was to be found in the real-life city, as well as in Shakespeare’s dramas. These two characters were perceived by the Elizabethan theater audience as having distinct morals and values – traits that were based on geographical biases that had roots dating back centuries.

"There is no world without Verona walls."

-(Romeo; Act 3, scene 3 – Romeo and Juliet)

Georg Braun (1540 or 41-1622) and Frans Hogenburg (ca. 1539-1590?)

“Magnifica Illa Civitas Verona; Colonia Augusta Verona Nova Gallieniana,” from Civitates Orbis Terrarum

Cologne, Germany, 1582.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

Romeo and Juliet, 1596.

Romeo sorrowfully laments in act three, scene three of Romeo and Juliet, “There is no world without Verona walls.” Faced with banishment from Juliet, Romeo pleads with Friar Laurence to grant him any other fate than expulsion from Verona, and despite their affection for one another, Romeo and Juliet tragically cannot escape the animosity that their families had for each other. The 1582 map displayed here illustrates Verona, known as a center for art and architecture, in two views, complete with vignettes of perhaps the star-crossed lovers on the left, and the Arena – a remnant from the city’s importance in Roman times – on the right.

7. Eastern Europe

"Seem'd Athens as a paradise to me"

-(Hermia; Act 1, scene 1 – A Midsummer Night’s Dream)

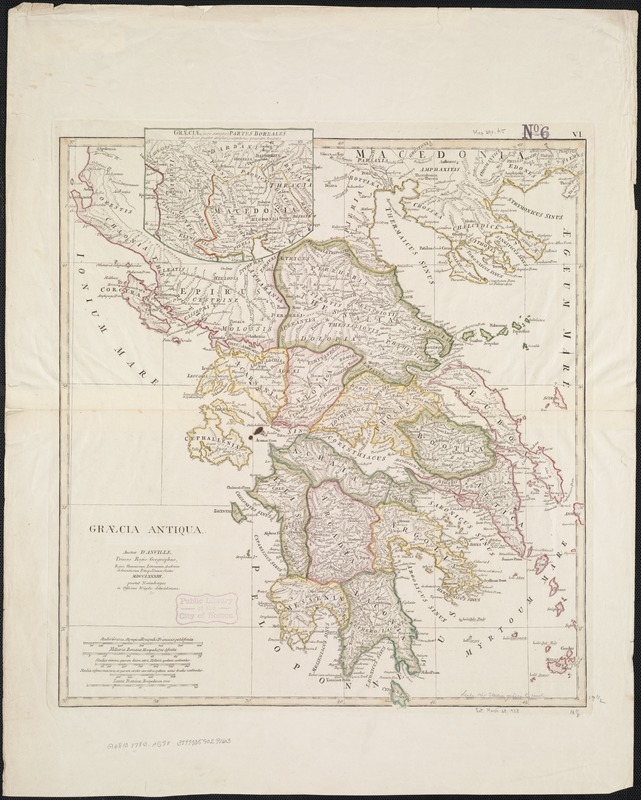

Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville (1697-1782)

Graeciae Antiquae

Nuremberg, 1783.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 1595-96.

Shakespeare’s whimsical play about four lovers and their romantic mix-ups takes place in classical Athens, depicted in this 18th century map, and in a nearby magical forest, home to fairies and mischievous spirits. Midsummer’s Eve – the summer solstice, or the longest day of the year - was celebrated in Europe before Christianity, and is a recognized holiday today. Customs symbolizing ancient fertility rites are still practiced, and the festival has close ties to the natural world. Shakespeare intertwines the ancient world with the fantasy realm of fairies in this comedy, which combines elements from folklore, classical writing, and his own imagination.

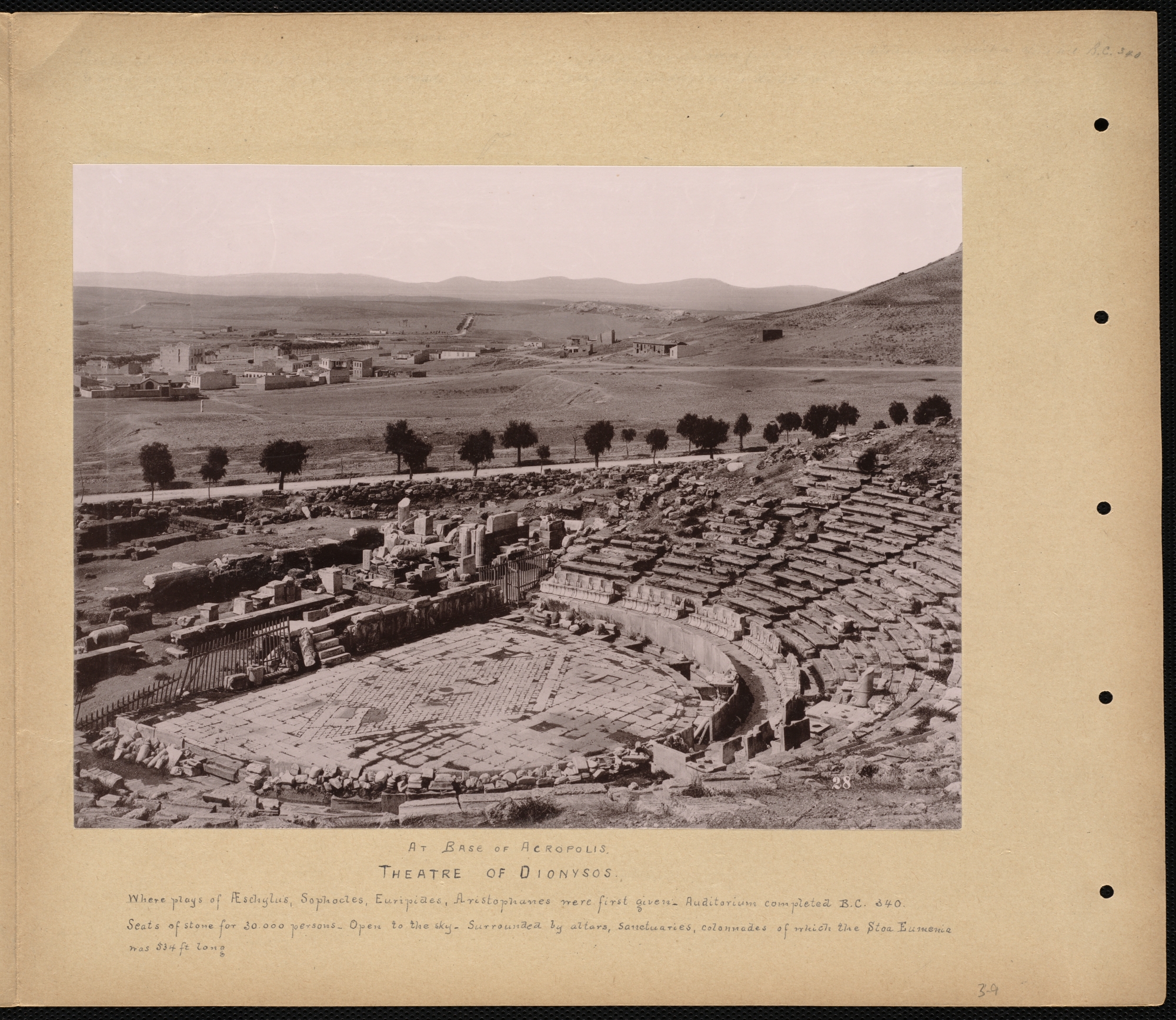

William Vaughn Tupper (1835-1898)

“At Base of Acropolis. Theatre of Dionysos,” detail from Tupper Scrapbooks Volume 3, Athens

[Athens, Greece, 1893]. Reproduction, 2016.

Boston Public Library, Print Department.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 1596

Theatrical performance was an important art form in classical times, and the Greeks and Romans built many theaters to stage plays. The two theaters pictured above are found in Athens, adjacent to one another near the Acropolis. The theater in the top photograph hosted tragic, then later comedic dramas, beginning in 500 BCE, and is dedicated to the Greek god Dionysos – god of wine and ecstasy – whose annual festival historically featured the performance of a tragedy. Comedies became more popular in the following century, and these too were dedicated to Dionysos. The odeon pictured at the bottom served as a concert hall for musicians or speakers, and was where players rehearsed for larger productions in the Theatre of Dionysos.

Bernard Sleigh (1872-1954)

An Anciente Mappe of Fairyland Newly Discovered and Set Forth

London, 1917.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 1596

Much of A Midsummer Night’s Dream takes place in a fantastic forest, separate from the more realistic court setting. Shakespeare borrowed from folktales of fairies and sprites in his comedy, and made these fantastic creatures come to life after his characters fell asleep. This dream world is illustrated in this pictorial map, originally created to amuse the author’s children. Fairyland depicts places from nursery rhymes, fairy tales, Arthurian legends and folktales of many cultures, and includes the Bard’s characters Oberon, King of the Fairies, his Queen Titania and her attendants, and the mischievous sprite Puck. In this play, the mythological worlds of Athens and Fairyland combine to provide a setting where anything is possible.

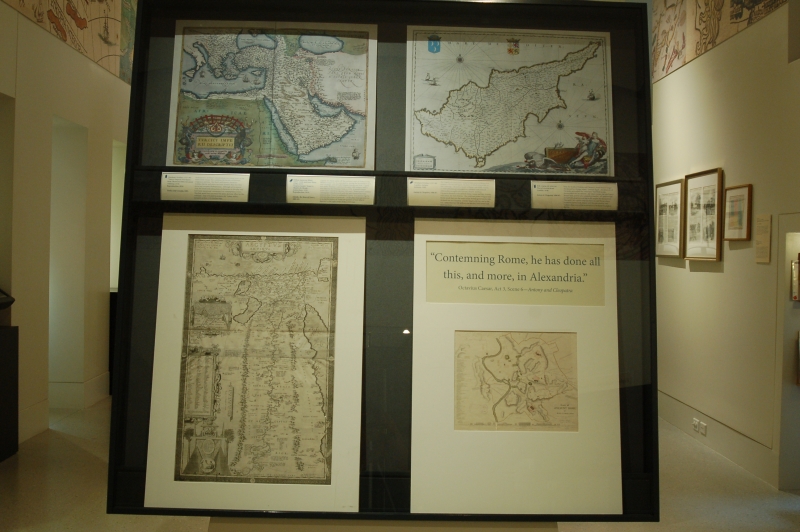

8. Asia & Africa

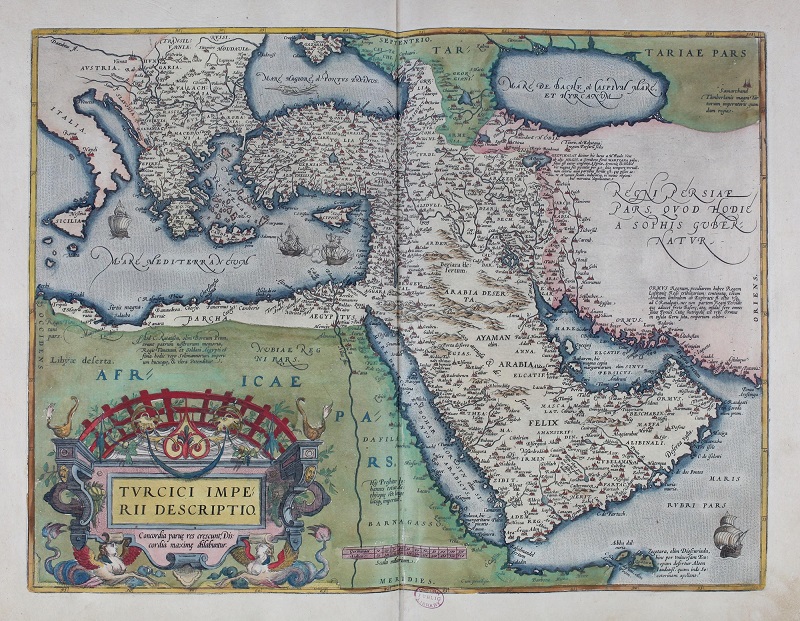

Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598)

“Turcici Imperii Descriptio,” from Theatrum Orbis Terrarum

Antwerp, 1570. Reproduction, 2016.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

Troilus and Cressida, 1601.

Shakespeare’s “problem” comedy about two lovers in the midst of the Trojan War combines the themes of dishonor, vengeance and loss. The Bard’s well-known characters Achilles, Hector and others are from Homer’s Iliad, but their stories are uniquely Shakespearian. Although set in ancient Troy, the events and interactions of characters in this play may have been intentional commentary on contemporary events, particularly the War of the Theatres with Ajax as a version of Ben Jonson. This link would have increased the play’s dramatic effect for the audience. Troy is located in modern-day Turkey, and is included on this 1570 Ortelius map.

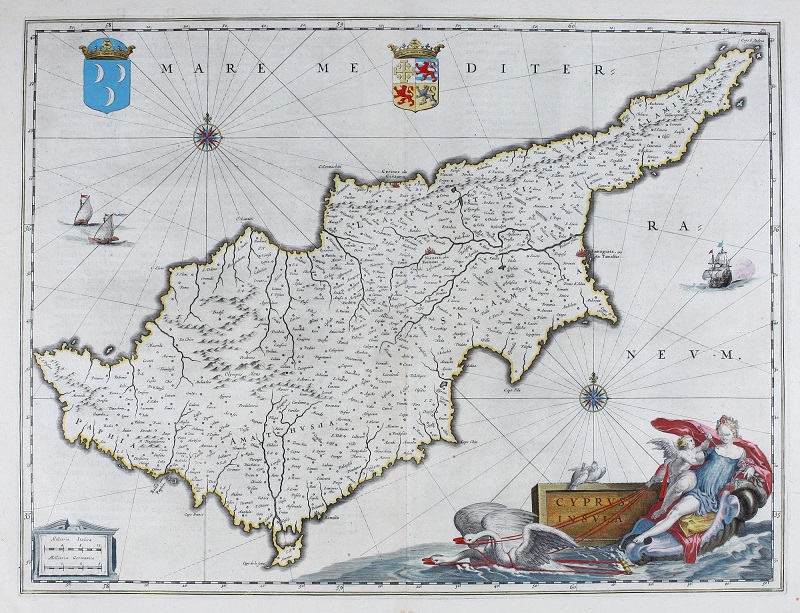

Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1571-1638) and Joan Blaeu (1596-1673)

“Cyprus Insula,” from Le Theatre du Monde, ou, Nouuel Atlas

Amsterdam, 1650. Reproduction, 2016.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

Othello, the Moor of Venice, 1601-02.

Cyprus, an island nation off the southern coast of Turkey in the Mediterranean Sea, became wealthy during the Renaissance as it was a strategic port of trade between Europe and Asia. Cyprus was under Venetian control in the early 16th century, until it was taken by the Ottoman Turks in 1570. It would remain under their control for the next 300 years. Shakespeare’s military commander Othello travels with his wife Desdemona from cosmopolitan Venice to embattled Cyprus. In a jealous rage he commits the crime of uxoricide – in the place that was believed to be the birthplace of Aphrodite, the goddess of love, who is depicted in the right corner of this 1650 map.

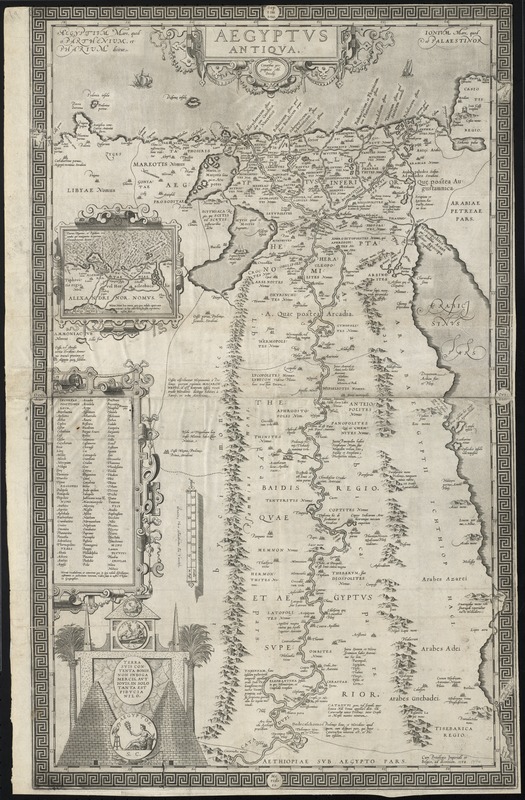

Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598)

Aegyptus Antiqua

Antwerp, 1584.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

Antony & Cleopatra, 1606-07.

The tragedy of Antony and Cleopatra takes place in the ancient empires of Rome and Egypt, the latter of which is depicted on this 1584 map. Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt, and Mark Antony, co-ruler of Rome are entangled in a romantic and political relationship fraught with betrayal, despair, and love. Cleopatra famously seduced both Julius Caesar and later Antony, with whom she had children. The combined power of Egypt and Rome struck fear into the hearts of the Roman government, who declared war on Cleopatra. Antony fought with her, and rather than face life without one another, both lovers took their own lives.

"Contemning Rome, he has done all this, and more,/In Alexandria."

(Octavius Caesar, Act 3, Scene 6, 1-2) Antony and Cleopatra

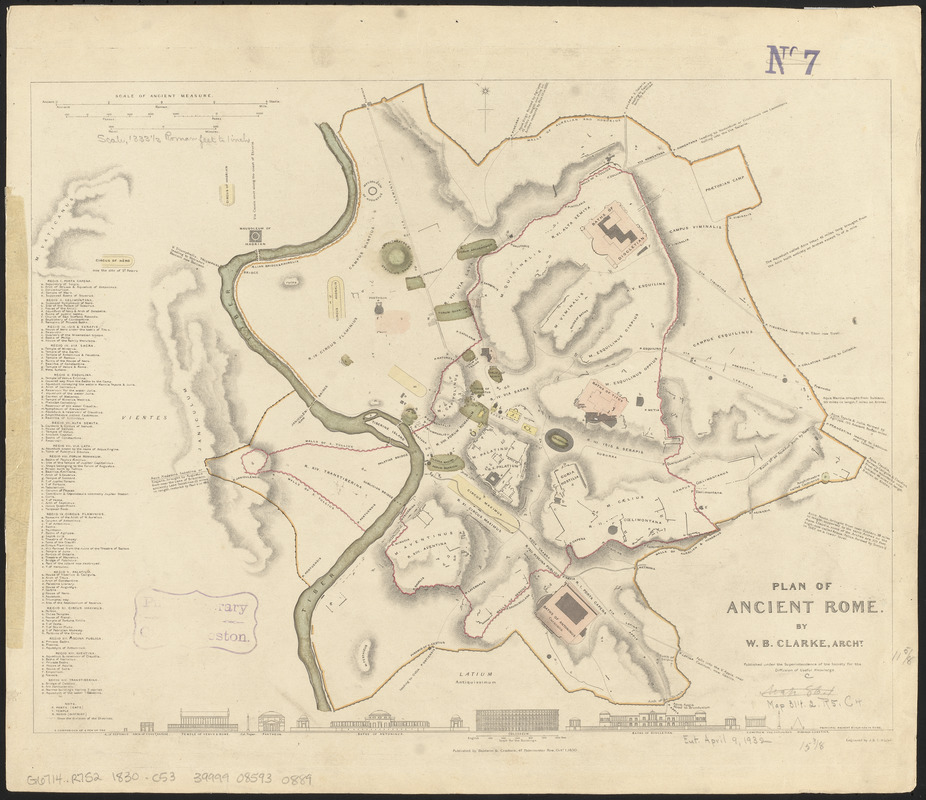

W.B. Clarke

Plan of Ancient Rome

London, 1830.

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

Antony & Cleopatra, 1606-07.

With the deaths of Antony and Cleopatra, Rome was no longer threatened by a foreign power – namely, Egypt. The character of Cleopatra personified the “otherness” that Shakespeare incorporated in his dramas – she was a woman, she was from a distant land, and she was extremely powerful – all qualities that stirred both attraction and fear in the people she encountered. This early-19th century map illustrates ancient Rome, where numerous scenes from Antony and Cleopatra unfolded, and includes depictions of the monuments to be found throughout the city.

Bibliography

"About Us." Shakespeare’s Globe, The Shakespeare Globe Trust, 2013. Web. <http://www.shakespearesglobe.com/about-us>.

Allison, Amy. Shakespeare’s Globe. San Diego: Lucent Books, 2000. Print. [PR2920 .A56 2000]

"Anne Hathaway’s Cottage." Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Web. <https://www.shakespeare.org.uk/visit/anne-hathaways-cottage/>.

"Antony and Cleopatra." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 30 Jun. 2016 <http://library.eb.com/levels/reference/article/136>.

Armstrong, Jane. The Arden Dictionary of Shakespeare Quotations. Walton-on-Thames: Thomas Nelson, 1999. Print. [PR2892 .A69 1999x]

Barber, Peter. "Was Elizabeth I Interested in Maps – and Did It Matter?" Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 14 (2004): 185-198. Web. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/3679314>.

"Basque Country." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 5 Jul. 2016. <http://library.ebonline.com/levels/adults/article/13647>.

Black Africans in Renaissance Europe, edited by T.F. Earle and K.J.P. Lowe. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005. Print.

Bouzrara, Nancy and Tom Conley. "Chapter 14: Cartography and Literature in Early Modern France." In The History of Cartography, Volume 3: Cartography in the European Renaissance, edited by David Woodward, 427-437. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007. Web. <http://www.press.uchicago.edu/books/HOC/HOC_V3_Pt1/HOC_VOLUME3_Part1_chapter14.pdf>.

Brotton, Jerry. Trading Territories Mapping the Early Modern World. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998. Print. [GA201 .B75 1998]

"Byzantine Empire." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., Web. 19 Jul. 2016. <http://library.ebonline.com/levels/adults/article/106111>.

Cachey Jr., Theodore J. "Chapter 16: Maps and Literature in Renaissance Italy." In The History of Cartography, Volume 3: Cartography in the European Renaissance, edited by David Woodward, 450-460. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007. Web. <http://www.press.uchicago.edu/books/HOC/HOC_V3_Pt1/HOC_VOLUME3_Part1_chapter16.pdf>.

"Cleopatra." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 19 Jul. 2016. <http://library.ebonline.com/levels/adults/article/24335>.

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. Coleridge on Shakespeare: The Text of the Lectures of 1811-12, edited by R.A. Foakes. Charlottesville: The University Press of Virginia, 1971. Print. [PR2899 .C58 1971]

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. Coleridge's Criticism of Shakespeare, edited by R.A. Foakes. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1989. Print. [PR2975 .C65 1989]

Conley, Tom. "Chapter 12: Early Modern Literature and Cartography: An Overview." In The History of Cartography, Volume 3: Cartography in the European Renaissance, edited by David Woodward, 401-411. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007. Web.

<http://www.press.uchicago.edu/books/HOC/HOC_V3_Pt1/HOC_VOLUME3_Part1_chapter12.pdf>.

Cormack, Lesley B. "Chapter 24: Maps as Educational Tools in the Renaissance." In The History of Cartography, Volume 3: Cartography in the European Renaissance, edited by David Woodward, 622-636. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007. Web. <http://www.press.uchicago.edu/books/HOC/HOC_V3_Pt1/HOC_VOLUME3_Part1_chapter24.pdf>.

"Cyprus." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 19 Jul. 2016. <http://library.ebonline.com/levels/adults/article/109746>.

Davis, Michael Justin. The England of William Shakespeare. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1987. Print. [PR2910.D38 1987x]

De Grazia, Margreta. Hamlet Without Hamlet. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007. Print. [PR2807 .D38 2007x]

Dickson, Andrew. "Global Shakespeare." British Library. British Library Board. Web. <http://www.bl.uk/shakespeare/articles/global-shakespeare>.

Dickson, Andrew. "Multiculturalism in Shakespeare’s Plays." British Library. British Library Board. Web. <http://www.bl.uk/shakespeare/articles/multiculturalism-in-shakespeares-plays>.

Dickson, Andrew. "Shakespeare’s Life." British Library. British Library Board. Web. <http://www.bl.uk/shakespeare/articles/shakespeares-life>.

"Dionysus." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 13 Jul. 2016. <http://library.ebonline.com/levels/adults/article/30551>.

Dobson, Michael and Stanley Wells, eds. The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2015. Print. [PR2892.O94 2015x]

Flachmann, Michael. The Moral Geography of Othello. Web. 19 Jul. 2016. <http://www.bard.org/study-guides/the-moral-geography-of-othello>.

Gillies, John. Shakespeare and the Geography of Difference. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1994. Print. [PR3014 .G55 1994]

"The Globe." Shakespeare’s Globe. The Shakespeare Globe Trust, 2013. Web. <http://www.shakespearesglobe.com/uploads/files/2014/01/the_globe.pdf>.

Greenblat, Stephen. Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2004. Print.

Griffith, Eva. "William Shakespeare." In Europe, 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World, edited by Jonathan Dewald. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2004. Biography in Context. Web. <http://ic.galegroup.com/ic/bic1/ReferenceDetailsPage/ReferenceDetailsWindow?zid=1a7d10eee0ab69a0e251ff8c248b15c4&action=2&catId=&documentId=GALE%7CK3404901040&userGroupName=clov94514&source=Bookmark&u=clov94514&jsid=787ac70aa8b9668788c0d78146adcc8e>.

Gurr, Andrew. Rebuilding Shakespeare’s Globe. New York: Routledge, 1989. Print. [PR2920 .G87 1989]

"Helsingør." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 30 Jun. 2016 <http://library.eb.com/levels/referencecenter/article/39934>.

"Henry VI, Part 1." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 30 Jun. 2016. <http://library.ebonline.com/levels/reference/article/3149>.

Hoenselaars, A. J. Images of Englishmen and Foreigners in the Drama of Shakespeare and His Contemporaries A Study of Stage Characters and National Identity in English Renaissance Drama, 1558-1642. Rutherford, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press; London: Associated University Presses, 1992. Print. [PR658.C47 H64 1992]

"Italy." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 5 Jul. 2016. <http://library.ebonline.com/levels/adults/article/106448>.

Jackson, Gabriele Bernhard. "Witches, Amazons, and Shakespeare’s Joan of Arc." English Literary Renaissance, 18.1 (1988): 40-65. Web. 19 Sep. 2016. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/3257853>.

Johanyak, D.L. Shakespeare’s World. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2004. Print. [PR2895.J64 2004]

"Julius Caesar." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 30 Jun. 2016 <http://library.eb.com/levels/reference/article/3167>.

Karrow, Robert. "Chapter 23: Centers of Map Publishing in Europe, 1472–1600." In The History of Cartography, Volume 3: Cartography in the European Renaissance, edited by David Woodward, 611-621. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007. Web.

<http://www.press.uchicago.edu/books/HOC/HOC_V3_Pt1/HOC_VOLUME3_Part1_chapter23.pdf>.

Karrow, Robert W., Jr. Mapmakers of the sixteenth century and their maps: bio-bibliographies of the cartographers of Abraham Ortelius, 1570. Chicago: Speculum Orbis Press, 1993. Print. [GA198 .K37 1993x]

Kernodle, George R. From Art to Theatre Form and Convention in the Renaissance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1944. Print.

Kernodle, George R. The Theatre in History. Fayetteville, Ark.: University of Arkansas Press, 1989. Print. [PN2037 .K38 1989]

Le Corbeiller, Clare. "Miss America and her sisters: personification of the four parts of the world." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 19.8 (1961): 209-223. Web. 21 Sep. 2016. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/3257853>.

Levin, Carole, and John Watkins. Shakespeare’s Foreign Worlds National and Transnational Identities in the Elizabethan Age. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009. Print. [PR2989 .L438 2009]

"Love’s Labour’s Lost." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 30 Jun. 2016. <http://library.eb.com/levels/adults/article/152>.

"Mark Antony." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., Web. 19 Jul. 2016. <http://library.ebonline.com/levels/adults/article/7914#363.toc>.

Matei-Chesnoiu, Monica. Re-imagining Western European Geography in English Renaissance Drama. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. Print. [R658.G46 M38 2012]

McGrane, Bernard. Beyond anthropology: society and the other. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989. Print. [GN33 .M34 1989]

Melion, Walter S. "Ad Ductum Itineris Et Dispositionem Mansionum Ostendendam: Meditation, Vocation, and Sacred History in Abraham Ortelius’s ‘Parergon’." The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 57, Place and Culture in Northern Art (1999): 49-72. Web. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/20169142>.

"The Merchant of Venice." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 30 Jun. 2016. <http://library.eb.com/levels/reference/article/195>.

"A Midsummer Night’s Dream." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 30 Jun. 2016. <http://library.eb.com/levels/reference/article/181>.

"Midsummer’s Eve." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 11 Jul. 2016. <http://library.ebonline.com/levels/adults/article/438708>.

Mullan, John. "An Introduction to Shakespeare’s Comedy." British Library. British Library Board. <http://www.bl.uk/shakespeare/articles/an-introduction-to-shakespeares-comedy>.

Mulryne, J.R., and Margaret Shewring, eds. Shakespeare’s Globe Rebuilt. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997. Print. [PR2920.S454 1997x]

"Navarra." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 5 Jul. 2016. <http://library.ebonline.com/levels/adults/article/55078>.

"Odeum." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 13 Jul. 2016. <http://library.ebonline.com/levels/adults/article/56763>.

"Othello." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 30 Jun. 2016. <http://library.eb.com/levels/reference/article/21>.

The Oxford Handbook of Shakespeare, edited by Arthur F. Kinney. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2012. Print. [PR2976 .O87 2012]

Paoletti, John T., and Gary Radke M. Art in Renaissance Italy. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2001. Print.

"Philip II." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 1 Jul. 2016. <http://library.ebonline.com/levels/adults/article/59673>.

Picard, Liza. "Cities in Elizabethan England." British Library. British Library Board. Web. <http://www.bl.uk/shakespeare/articles/cities-in-elizabethan-england>.

Picard, Liza. "Exploration and trade in Elizabethan England." British Library. British Library Board. Web. <http://www.bl.uk/shakespeare/articles/exploration-and-trade-in-elizabethan-england>.

Pinet, Simone. "Chapter 18: Literature and Cartography in Early Modern Spain: Etymologies and Conjectures." In The History of Cartography, Volume 3: Cartography in the European Renaissance, edited by David Woodward, 469-476. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007. Web. <http://www.press.uchicago.edu/books/HOC/HOC_V3_Pt1/HOC_VOLUME3_Part1_chapter18.pdf>.

Playing the Globe: Genre and Geography in English Renaissance Drama, edited by John Gillies and Virginia Mason Vaughan. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1998. Print. [PR678.G46 P57 1998]

Rasmussen, Eric and Ian DeJong. "Shakespeare’s London." British Library. British Library Board. Web. <http://www.bl.uk/shakespeare/articles/shakespeares-london>.

Rasmussen, Eric and Ian DeJong. "Shakespeare’s Playhouses." British Library. British Library Board. Web. <http://www.bl.uk/shakespeare/articles/shakespeares-playhouses>.

"Romeo and Juliet." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 30 Jun. 2016. <http://library.eb.com/levels/reference/article/100>.

Ryan, Kiernan. "An Introduction to Shakespearean Tragedy." British Library. British Library Board. Web. <http://www.bl.uk/shakespeare/articles/an-introduction-to-shakespearean-tragedy>.

Shakespeare: An Oxford Guide, edited by Stanley Wells and Lena Cowen Orlin. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2003. Print. [PR2976 .S333 2003]

Shakespeare: The Complete Works, edited by G.B. Harrison. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1968. Print. [PR2754 .H36 1968x]

Shakespeare, William. Henry VI, Part 1. 1623 First Folio. Folger Shakespeare Library. Web. <http://www.folger.edu/henry-vi-part-1>.

Shakespeare: World Views, edited by Heather Kerr, Robin Eaden, and Madge Mitton. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1996. Print. [PR2976 .S3388 1996]

"Shakespeare’s Birthplace." Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Web. <https://www.shakespeare.org.uk/visit/shakespeares-birthplace/>.

"Shakespeare’s Life and Times." Royal Shakespeare Company. Royal Shakespeare Company. Web. <https://www.rsc.org.uk/shakespeares-life-and-times/>.

"Spain." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 1 Jul. 2016. <http://library.ebonline.com/levels/adults/article/108580>

"Theatre of Dionysus." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 13 Jul. 2016. <http://library.ebonline.com/levels/adults/article/30552>.

"Troilus and Cressida." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 30 Jun. 2016. <http://library.eb.com/levels/reference/article/67>.

Turner, Henry S. "Chapter 13: Literature and Mapping in Early Modern England, 1520–1688." In The History of Cartography, Volume 3: Cartography in the European Renaissance, edited by David Woodward, 412-426. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007. Web. <http://www.press.uchicago.edu/books/HOC/HOC_V3_Pt1/HOC_VOLUME3_Part1_chapter13.pdf>.

"Venice." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 5 Jul. 2016. <http://library.ebonline.com/levels/adults/article/108773>

"Verona." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 8 Jul. 2016. <http://library.ebonline.com/levels/adults/article/75136>.

Watts, Pauline Moffitt. "Chapter 11: The European Religious Worldview and Its Influence on Mapping." In The History of Cartography, Volume 3: Cartography in the European Renaissance, edited by David Woodward, 382-400. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007. Web. <http://www.press.uchicago.edu/books/HOC/HOC_V3_Pt1/HOC_VOLUME3_Part1_chapter11.pdf>.

"Western theatre." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 13 Jul. 2016. <http://library.ebonline.com/levels/adults/article/105998>.

Whitfield, Peter. "Chapter Four: The Theatre of the World." In The Image of the World: 20 Centuries of World Maps. San Francisco: Pomegranate Artbooks in association with the British Library, 1994. Print. [Z692.M3 .W48 1994]

Whitfield, Peter. Illustrating Shakespeare. London, U.K.: British Library, 2013. Print. [PR2883 .W47 2013x]

"William Shakespeare." Britannica Library. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2016. Web. 30 Jun. 2016. <http://library.eb.com/levels/reference/article/109536>.

"William Shakespeare." Shakespeare’s Globe, The Shakespeare Globe Trust, 2013. Web. <http://www.shakespearesglobe.com/uploads/files/2014/06/william_shakespeare.pdf>.

Ziegler, Georgianna. "En-gendering the world: the politics and theatricality of Ortelius’s titlepage." European Iconography east and west: selected papers of the Szeged International Conference, June 9-12, 1993, edited by György E. Szönyi, E.J. Brill, 1996, pp. 128-145.

Credits

Curator

Stephanie Cyr

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center Staff

Lauren Chen, Cataloger

Connie Chin, President

Alison Cody, Development Manager

Stephanie Cyr, Assistant Curator of Maps

Ronald Grim, Curator of Maps

Dory Klein, Education Assistant

Michelle LeBlanc, Director of Education

Evan Thornberry, Reference and

Geospatial Librarian

Catherine Wood, Office Manager

Boston Public Library Staff

Communications Dept.

Facilities Dept.

IT Dept.

Graphic Design and Production

Neva Corbo-Hudak Graphic Design

Framing and Matting

Andrew Leonard

Contributors to the Exhibition

Stephanie Cyr

Ronald E. Grim

Special Thanks

Robert Augustyn, Martayan Lan Rare Books and Maps

Elle Despres

Massachusetts Cultural Council

Jay Moschella, Curator of Rare Books, Boston Public Library

John Tobin, PhD, Professor of English, College of Liberal Arts, UMass Boston

Press

Shakespeare’s Here and Everywhere Exhibition

Museum Open House, December 8, 2016

How Maps Shaped Shakespeare

Smithsonian.com, December 5, 2016

Travels with Shakespeare

The Boston Globe, October 28, 2016

Mapping How Shakespeare Saw the World

CityLab, September 21, 2016

Map Exhibit Honors 400th Anniversary of Shakespeare’s Death

Associated Press, September 19, 2016

Map Out Shakespeare’s World

MassLive, September 18, 2016