Introduction

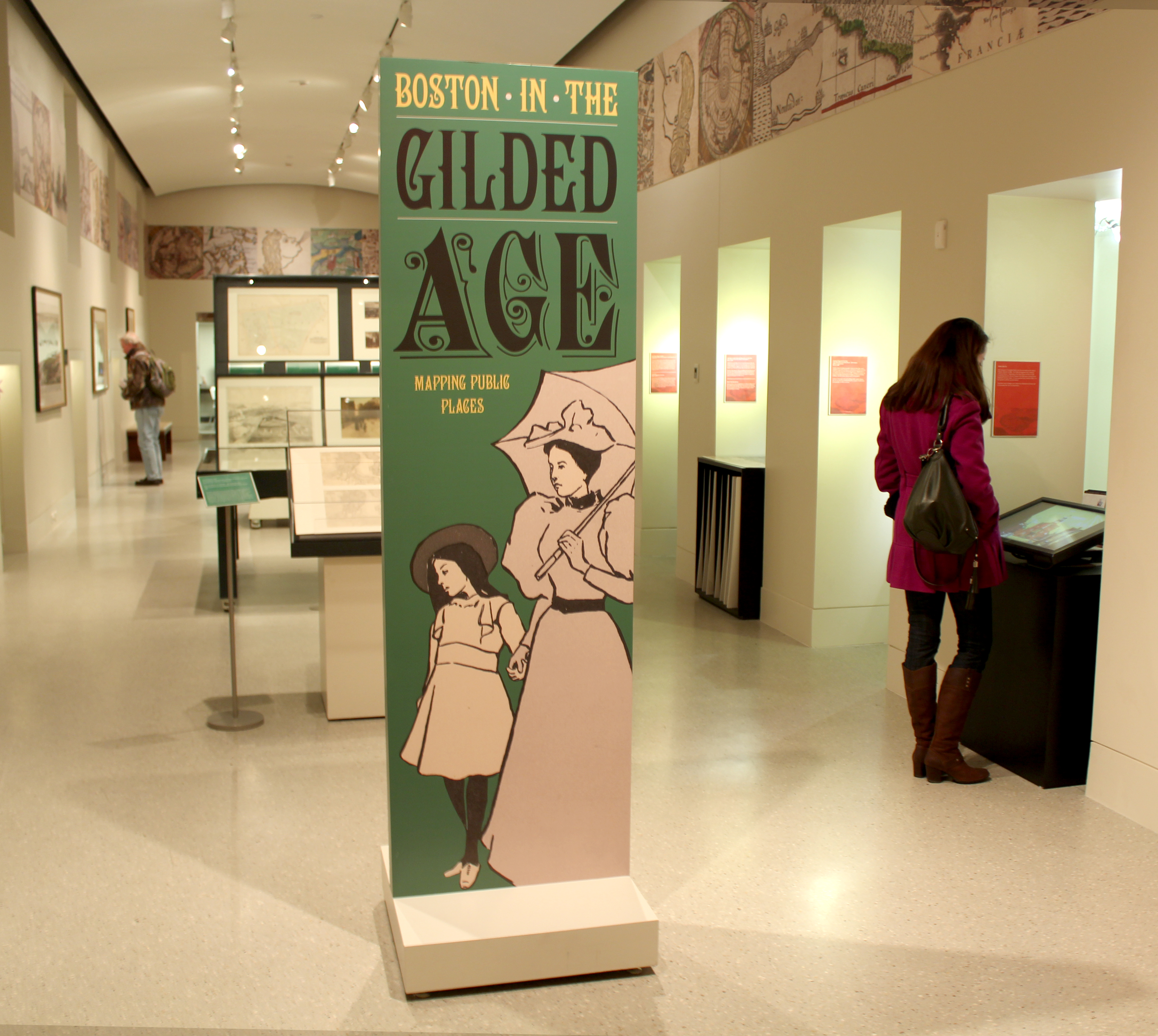

The Gilded Age–the era from the late 1860s to the late 1890s–was a period of significant growth and transformation in Boston. Ingenious engineering projects allowed the city to expand, and a devastating fire led to swift and progressive redevelopment of the commercial district. Designed to document Boston’s radically changing geography, this exhibition focuses on the evolving street pattern and emerging park system, developed for the City’s growing population.

This story begins with the Boston Common and Public Garden. Moving west, the exhibition examines the growth of open spaces in Back Bay, then south to Frederick Law Olmsted’s Emerald Necklace, finishing with the development of Copley Square – the permanent home of the Boston Public Library.

1. Filling in the Back Bay, 1858-1882

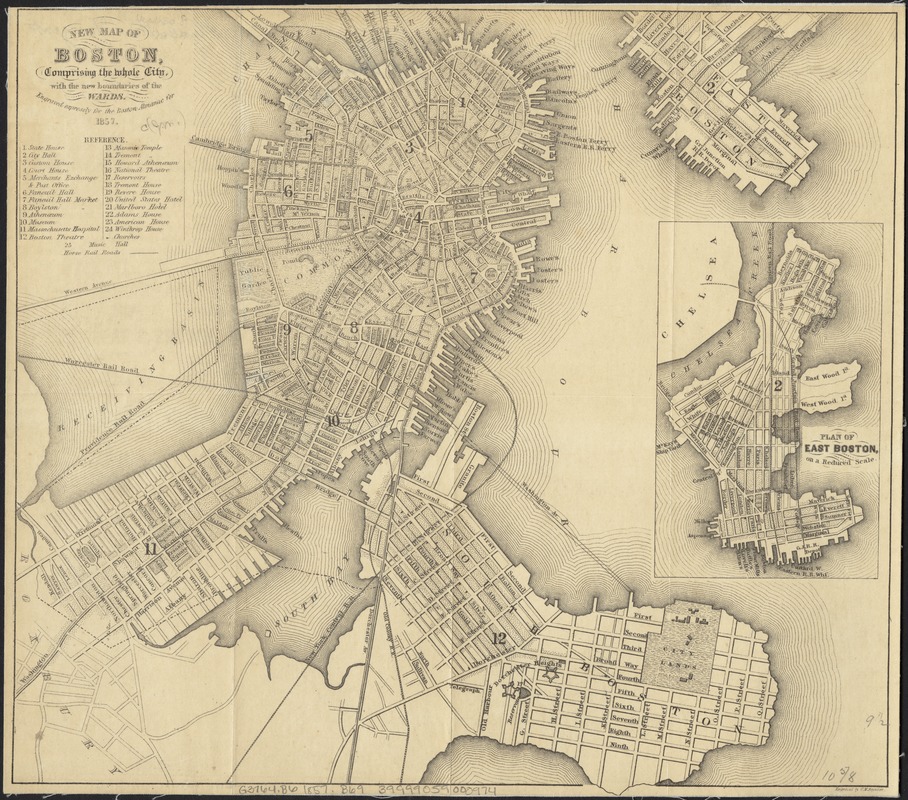

George W. Boynton

New Map of Boston, Comprising the Whole City, With the New Boundaries of the Wards

1857.

Prior to the Civil War, the area west of the Public Garden was marshland, as depicted in this 1857 map. By the late 1840s, the marsh had become so polluted it was considered a health hazard, and officials had no choice but to act. The solution was to fill in the quagmire, in a land reclamation project that would double the size of the original Boston peninsula. The project began in 1858 and finished in 1882.

Boston, Massachusetts. View of Back Bay in 1857

1857.

Courtesy Print Department.

The polluted marshland of the Back Bay is depicted in this 1857 photograph, taken on the eve of the landfill project. The project began in 1858 and finished in 1882.

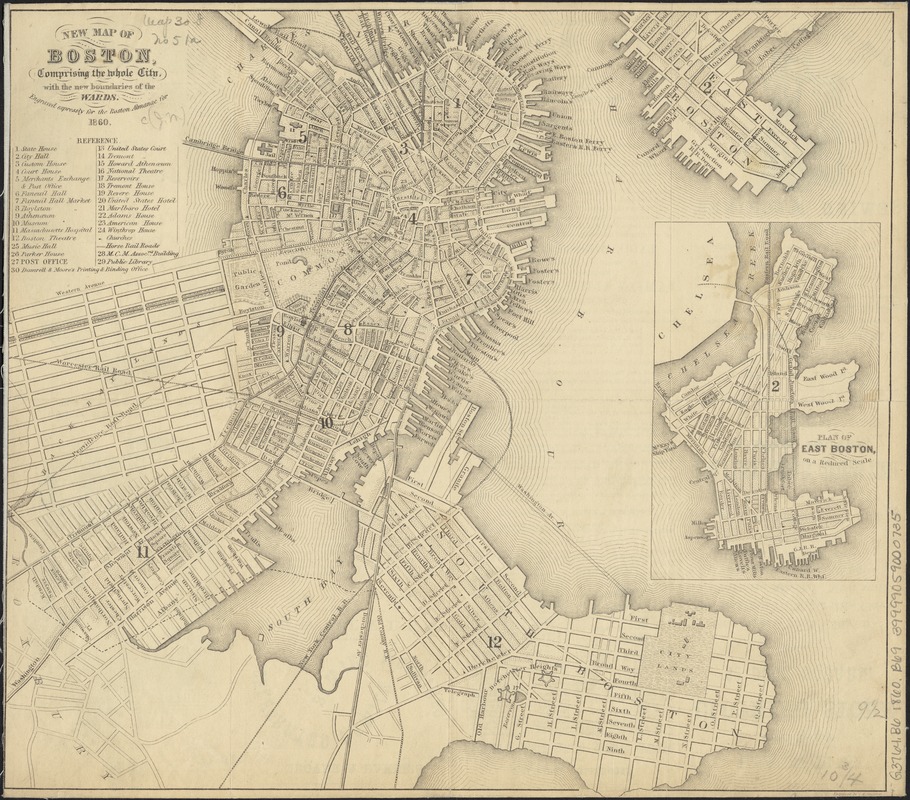

George W. Boynton

New Map of Boston. Comprising the Whole City, With the New Boundaries of the Wards

1860.

By the late 1840s, the marshland west of the Public Garden had become so polluted it was considered a health hazard, and officials had no choice but to act. The solution was to fill in the quagmire, in a land reclamation project that would double the size of the original Boston peninsula. The project began in 1858 and finished in 1882. This 1860 map illustrates proposed streets of the Back Bay. The area was designed as a grid with Commonwealth Avenue as the central boulevard of five east-west corridors, and eight north-south cross streets named for English nobility.

Back Bay

1895.

Courtesy Print Department.

This 1895 photograph depicts the completed Back Bay neighborhood. The area was designed as a grid with Commonwealth Avenue as the central boulevard of five east-west corridors, and eight north-south cross streets named for English nobility.

O.H. Bailey and J.C. Hazen

The City of Boston

1879.

This large and detailed aerial view depicts the city from the southeast as if the artist was positioned above South Boston. Consequently, he placed the rail lines terminating in the vicinity of present-day South Station and the busy eastern waterfront in the foreground, with the central business district dominating the central portion of the drawing. By 1879 the burned district had been rebuilt, and Back Bay had been mostly reclaimed, although the new real estate was only partially developed. The Common and Public Garden are focal points, highlighting the importance of these public places.

Albert E. Downs

Boston …

1899.

By the time this aerial view was published, the filling in and development of Back Bay was nearly complete, doubling the original size of the city. The Common and Public Garden are centrally located, with the new Back Bay neighborhood to the west. The burned district has not only been rebuilt, but has expanded to include a bustling waterfront, illustrating how Boston was an important regional commercial hub. As Boston’s business district grew, public places and green spaces had to be developed on the edges of the urbanized area.

2. The Great Boston Fire, 1872

Charles R. Parsons

“Bird’s-Eye View of Boston, Showing the Burned District” from Harper’s Weekly

November 30, 1872.

Gift of Bank of America.

The most devastating fire in Boston’s history began on the evening of November 9, 1872. Three weeks later, Harper’s Weekly published this view outlining the extent of the burned district. With a limited water supply, outdated infrastructure, cramped buildings and no horses to pull heavy equipment, firefighters struggled to extinguish the blaze that began at 83-85 Summer Street. Boston’s commercial center suffered severe losses by the time the fire had been fully quenched – nearly two days after it began.

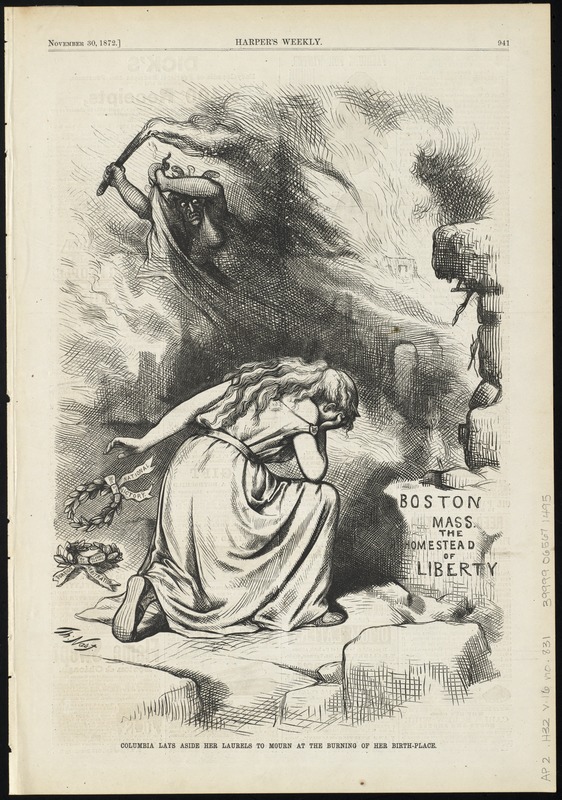

Thomas Nast

“Columbia Lays Aside Her Laurels to Mourn at the Burning of Her Birth-Place” from Harper’s Weekly

November 30, 1872.

Thomas Nast’s dramatic and symbolic representation of the devastation caused by the Great Fire was published in Harper’s Weekly, three weeks after the event. Columbia, the historical female personification of the United States, is depicted in despair at the destruction of the city. A hideous Gorgon sweeps fire across the sky, as Columbia shields her eyes from the monstrous flames that consume Boston – the proverbial birth place of liberty. Casting aside her victory laurels representing recent political events, the goddess is overcome by grief to see the “Athens of America” succumb to the inferno.

J.H. Bufford’s Lith. Words and music by C.A. White

Homeless To-Night or Boston in Ashes

1872.

Written by Boston’s preeminent song writer C.A. White, this somber ballad was told from the perspective of the two young girls portrayed on this sheet music cover. The youths are depicted fleeing the scene of the blaze which swept through the commercial district destroying many homes and businesses, and taking a number of lives. As the city crumbles around them, the girls sing, “Lone and weary through the streets we wander, for, we have no place to lay our heads, not a friend on earth is left to shelter us, for, both our parents now are dead.”

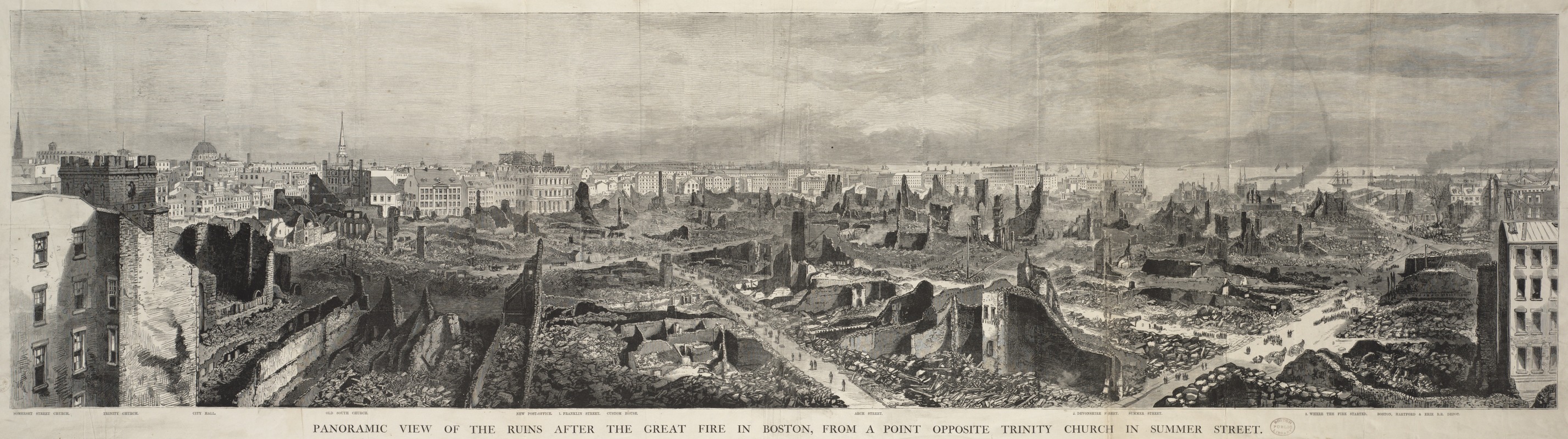

[After James Wallace Black]

Panoramic View of the Ruins After the Great Fire in Boston, From a Point Opposite Trinity Church in Summer Street

1872.

Courtesy Print Department.

The destruction left behind by the Great Fire of 1872 was colossal, as depicted in this panoramic view of the smoldering burned district, based on a photograph by J.W. Black. Sixty-five acres of buildings were lost in the blaze. This striking image shows a Boston that has literally been leveled, as firefighters resorted to detonating explosions and destroying buildings in the path, in a futile attempt to stop the spread of the fire. Remarkably, the area was rebuilt and back to business within two years.

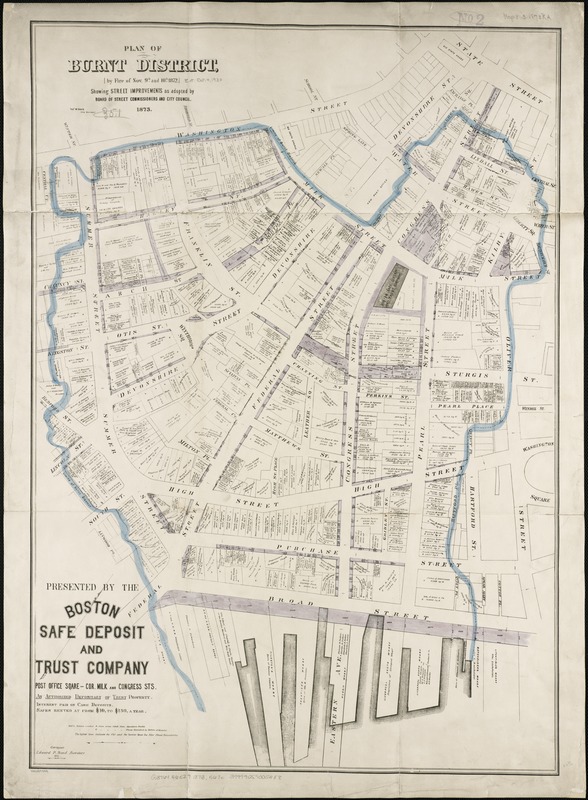

Thomas W. Davis

Plan of Burnt District (By Fire of Nov. 9th and 10th, 1872): Showing Street Improvements as Adopted by Board of Street Commissioners and City Council

1873.

The fire destroyed many businesses in the district including Boston’s publishing houses. However, the citizens’ spirit and civic pride were revealed, as they quickly rebuilt and implemented reforms in fire and building codes. This 1873 map outlines the burned district, and includes plans for improving streets within that vicinity. Realizing that poorly planned and overcrowded lanes had allowed the fire to spread so easily, the City widened seventeen streets and extended four in the area. Land was cleared to create Post Office Square, new firefighting infrastructure was constructed, and a new downtown rose out of the ashes.

3. Boston Common and Public Garden

John Bachmann

Bird’s Eye View of Boston

1850.

In this early aerial view by German artist John Bachmann, the city is depicted from the southwest. Looking directly at the Public Garden and the Common with the remainder of downtown greatly foreshortened, Bachmann highlights the city’s oldest and most prominent public places. The foreground is filled with water, as the natural land at this time ended at present-day Arlington Street. The Back Bay land reclamation project would not begin for another eight years.

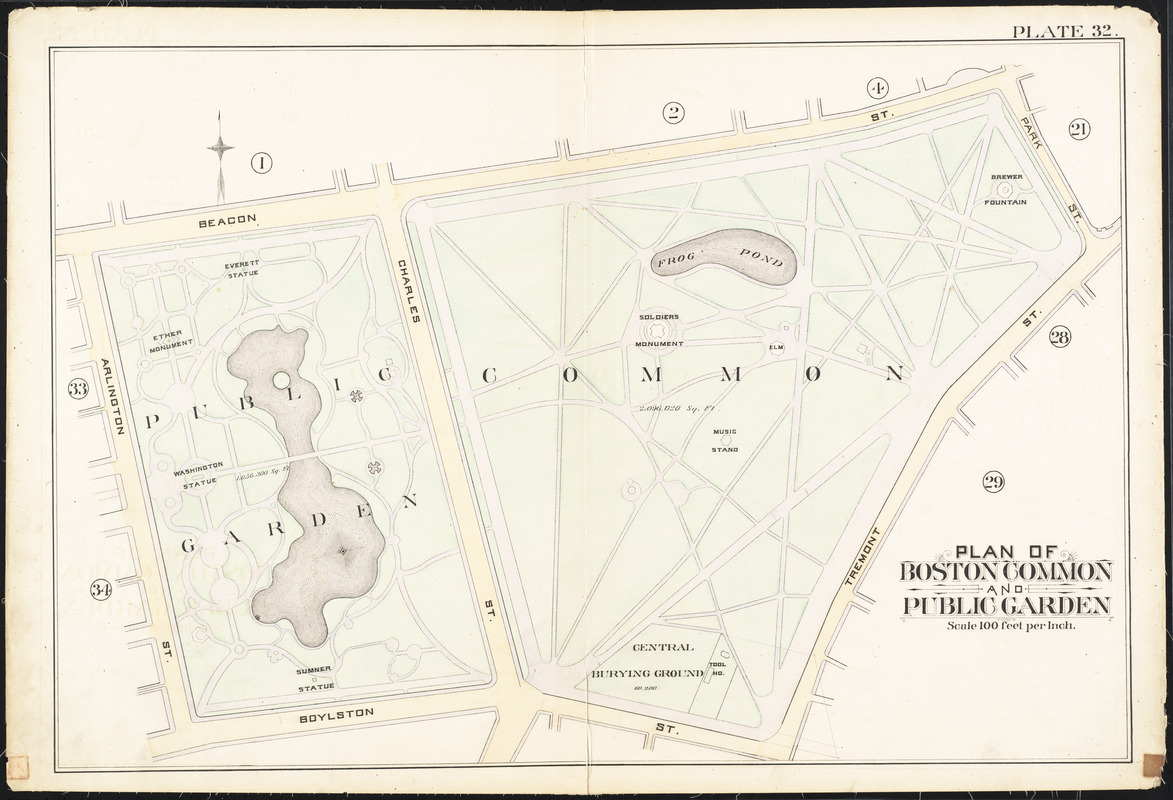

G.W. Bromley & Co.

“Plan of Boston Common and Public Garden,” plate 32 from Atlas of the City of Boston, Vol. 1

1888.

The story of Boston’s park system begins at the Boston Common – the oldest park in the country. This 50 acre pastoral expanse was originally used for grazing cattle, and was converted to park space in the early 1800s. Abutting the Common is the Public Garden – America’s first public botanical park. Completed in 1860, it was Boston’s answer to Central Park. Intended to encourage leisurely strolls while taking in the exotic plant-life, the Garden serves as the gateway to a vast network of green spaces throughout the city.

No. 13 Public Garden, Boston, Mass.

1880.

Courtesy Print Department.

This photograph of the Public Garden shows how the space was arranged to encourage meandering. Unlike the Common, whose straight throughways enabled quick passage across the city, the undulating pathways of the Public Garden encouraged visitors to linger and absorb the scenery. Whereas the Common had a utilitarian and pastoral feel, the Public Garden was a place that stimulated the senses, and incorporating art and a feeling of refinement into the space. At a time when ornamental garden design was in vogue, the Public Garden represented the best that a city of learned, cultured citizens could desire in an outdoor botanical space.

Tremont Street Mall, Boston Common

1880.

Courtesy Print Department.

This photograph of the Tremont Street Mall in Boston Common, whose straight throughways enabled quick passage across the city, is in stark contrast to the undulating pathways of the Public Garden which encouraged visitors to linger and absorb the scenery. The Common had a utilitarian and pastoral feel, whereas the Public Garden was a place that stimulated the senses, incorporating art and a feeling of refinement into the space.

4. Back Bay

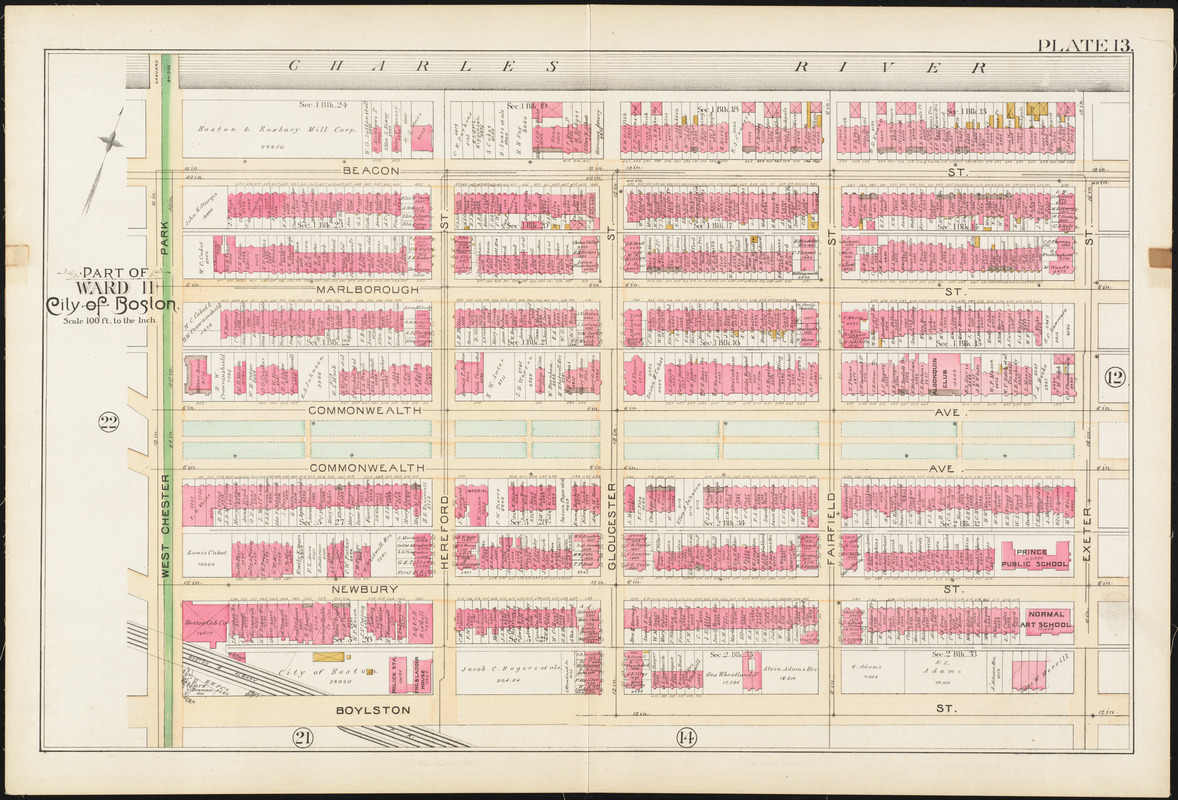

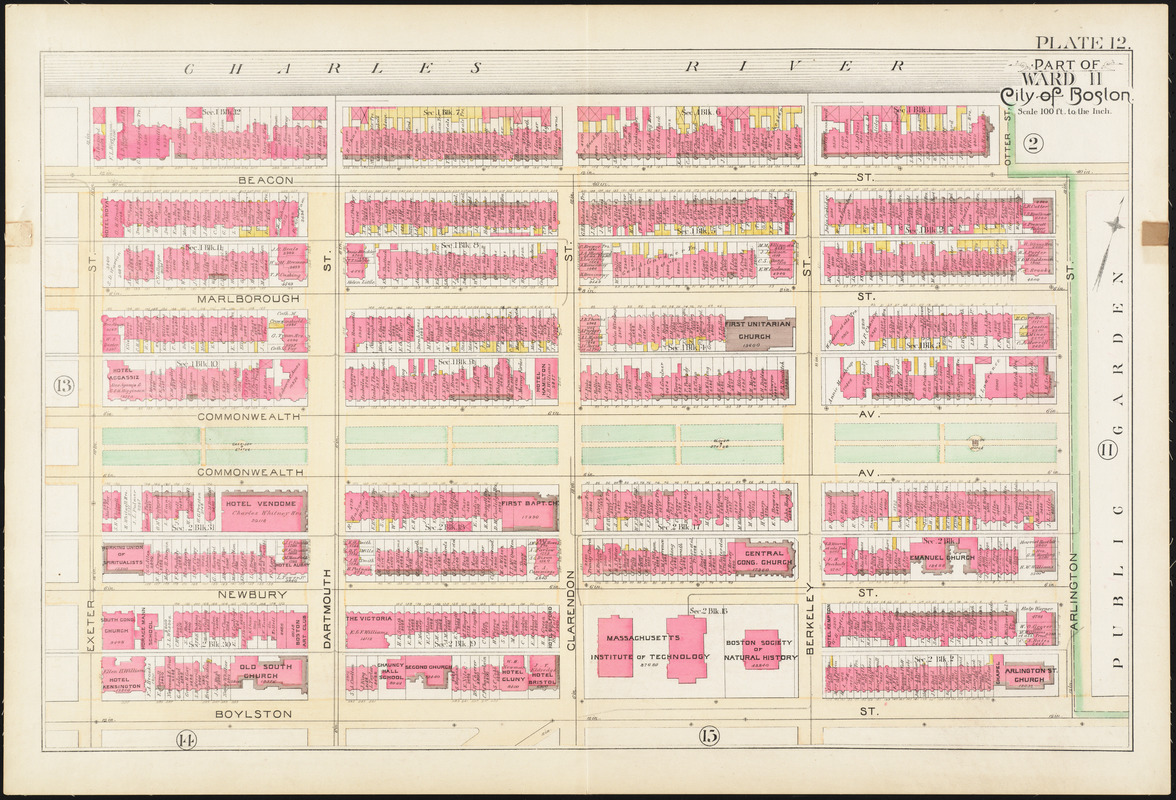

G.W. Bromley & Co.

“Part of Ward 11, City of Boston,” plate 13 from Atlas of the City of Boston, City Proper and Roxbury

1890.

Providing the link between the Public Garden and the Emerald Necklace, the Commonwealth Avenue Mall was Boston’s answer to majestic Parisian boulevards. Designed by architect Arthur Gilman, and incorporated into the park system in 1894, Commonwealth Avenue Mall was the centerpiece of the Back Bay’s widest and most manicured thoroughfare. The Mall extends from the Public Garden to present-day Massachusetts Avenue. To create a uniform and appealing space, strict building codes were enforced along the avenue. The result is a grand spatial corridor comprised of stately homes and deliberate green spaces.

This map shows the extent of the Mall from Exeter Street to West Chester Park (now Massachusetts Avenue).

G.W. Bromley & Co.

“Part of Ward 11, City of Boston,” plate 12 from Atlas of the City of Boston, City Proper and Roxbury

1890.

Providing the link between the Public Garden and the Emerald Necklace, the Commonwealth Avenue Mall was Boston’s answer to majestic Parisian boulevards. Designed by architect Arthur Gilman, and incorporated into the park system in 1894, Commonwealth Avenue Mall was the centerpiece of the Back Bay’s widest and most manicured thoroughfare. The Mall extends from the Public Garden to present-day Massachusetts Avenue. To create a uniform and appealing space, strict building codes were enforced along the avenue. The result is a grand spatial corridor comprised of stately homes and deliberate green spaces.This map shows the extent of the Mall from Arlington Street to Exeter Street.

Commonwealth Avenue in Process

1872.

Courtesy Print Department.

The development of Commonwealth Avenue was not a continuous process. As land was created, lots were sold and homes were built, although a recession in 1873 slowed sales for years. An 1872 photograph documents the area in the midst of construction.Overcrowding downtown was forcing professionals and business owners into the suburbs. In hopes of retaining a wealthy population in the city, Back Bay was developed to appeal to affluent sensibilities. Removed from the commercial district, with its beautiful residences, tree-lined boulevards, and cultural institutions, prosperous Bostonians were proud to call the area home.

No. 1 Commonwealth Ave., Boston, Mass.

(1878-1910).

Courtesy Print Department.

The development of Commonwealth Avenue was not a continuous process. As land was created, lots were sold and homes were built, although a recession in 1873 slowed sales for years.Overcrowding downtown was forcing professionals and business owners into the suburbs. In hopes of retaining a wealthy population in the city, Back Bay was developed to appeal to affluent sensibilities. Removed from the commercial district, with its beautiful residences, tree-lined boulevards, and cultural institutions, prosperous Bostonians were proud to call the area home. This photograph taken after 1878 documents the area as development was proceeding.

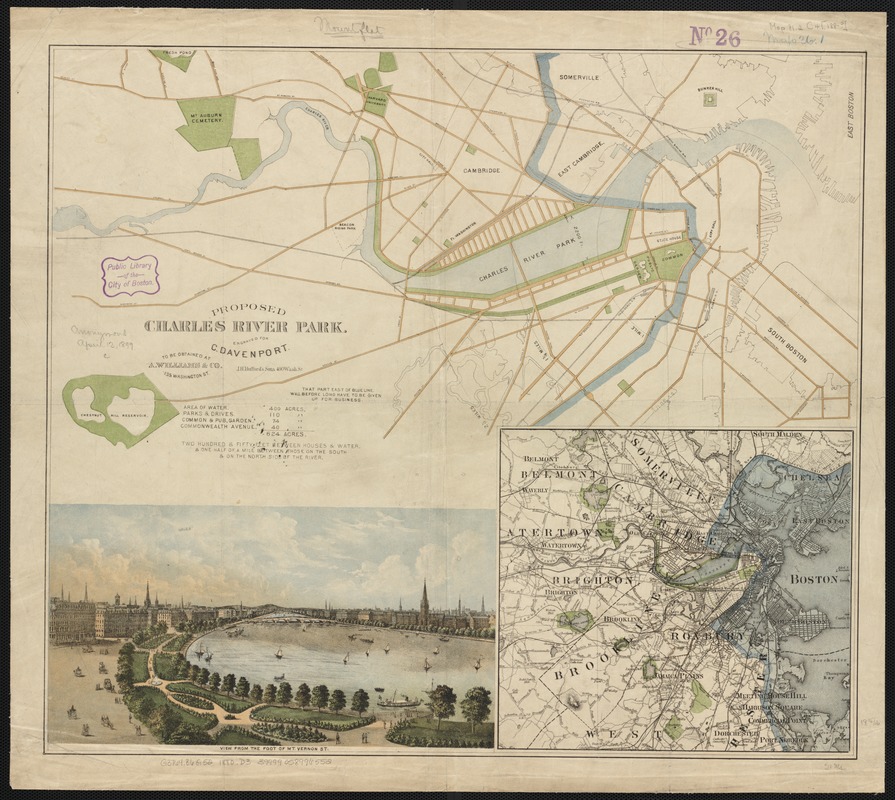

Charles Davenport

Proposed Charles River Park

1880.

Boston was home to numerous manufacturing companies in the late 19thcentury, where jobs tended to be sedentary and performed in closed, dirty spaces. To provide relief to factory workers from daily stresses, open spaces such as the Charles River Park were proposed.An 1880 broadside depicts the plan for an esplanade parallel to Commonwealth Avenue. This park, a literal “breathing place,” provided fresh air from the river in an attempt to cleanse the mind and body of not only Boston’s burdened factory worker, but of all citizens in the densely populated metropolis.

Developed for the residents of the overcrowded West End, Charlesbank was a revolutionary space. Designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, it provided two open-air gymnasiums, free preschool daycare services, and the first sandboxes for children. Previously located between Leverett and Cambridge Streets, the park was intended to lower the summertime death rate from cholera infantum that decimated the youth population in the area, as enlightened thinkers of the time saw parks as environmental preventatives to ill-health. Neighborhood youngsters are seen in this 1905 photograph enjoying the park.

5. Suburban Parks

Boston (Mass.) Park Department

Map of Boston and of a Part of its Suburbs, Showing Public Recreation Grounds, Burial Grounds and Certain Other Public Properties Generally Free From Buildings

1886.

Published during the height of the growth of green spaces throughout the city, this map shows the numerous areas where citizens could receive respite from the crowded city streets. Fully developed public recreation grounds were shown, as well as lands intended for future use as park spaces.In addition to parks, numerous cemeteries were also included. Before the establishment of Boston’s park system, garden cemeteries such as Mount Hope in Mattapan served as sites of outdoor recreation for the local residents, and became an impetus for the development of municipal parks.

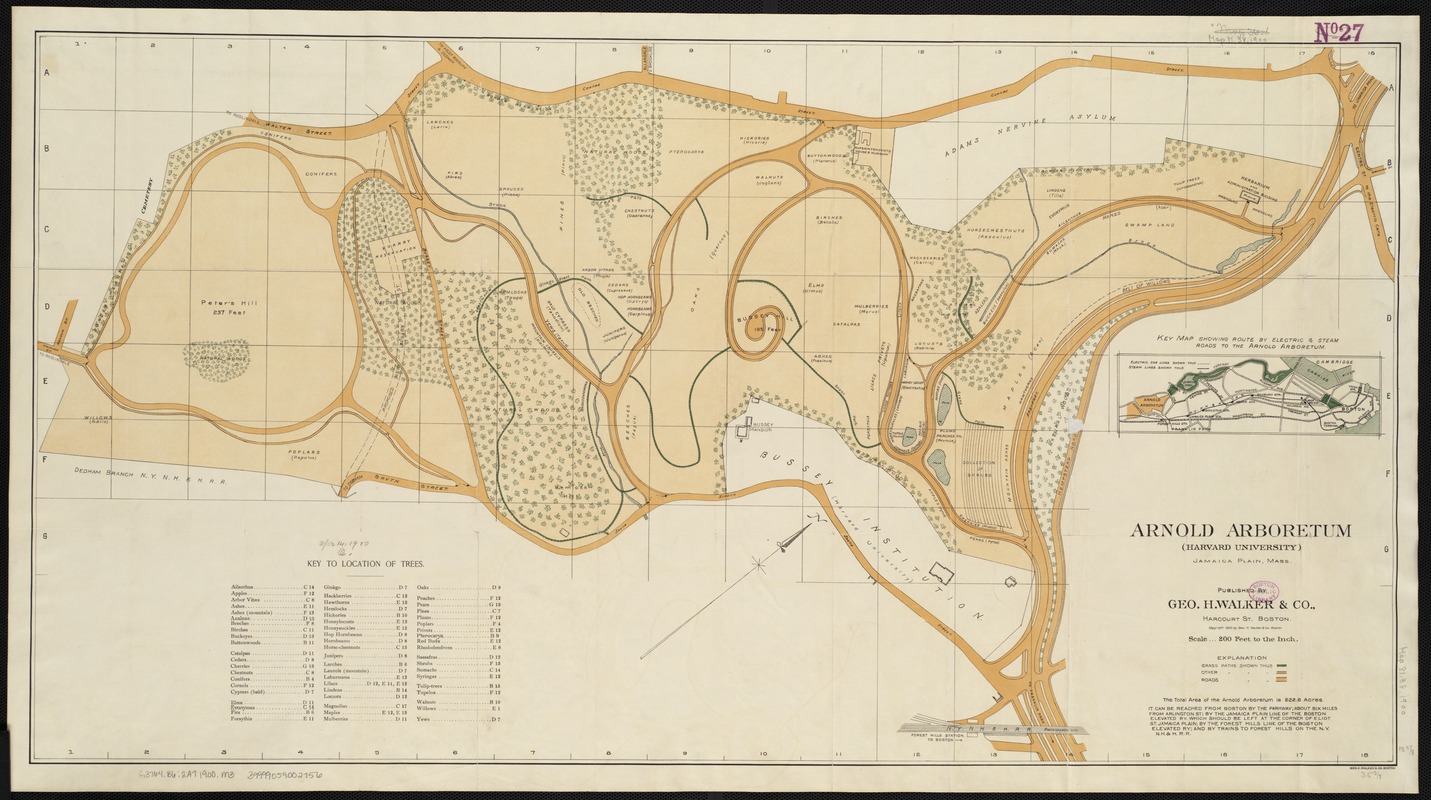

Geo. H. Walker & Co.

Arnold Arboretum (Harvard University), Jamaica Plain, Mass.

1900.

The Emerald Necklace’s Arnold Arboretum was the result of a collaboration between Frederick Law Olmsted and amateur horticulturalist Charles Sargent. The site was once the Bussey Family farm, an informal park that was given to Harvard in 1872 for agricultural education.In an arrangement between Harvard and the City of Boston, the Arboretum became part of the park system in 1882. Serving as a park and an educational institution has allowed for preservation of many original features of the Arboretum, as this 1900 map shows the location of trees, shrubs, and pathways designed by Olmsted, which remain unchanged to this day.

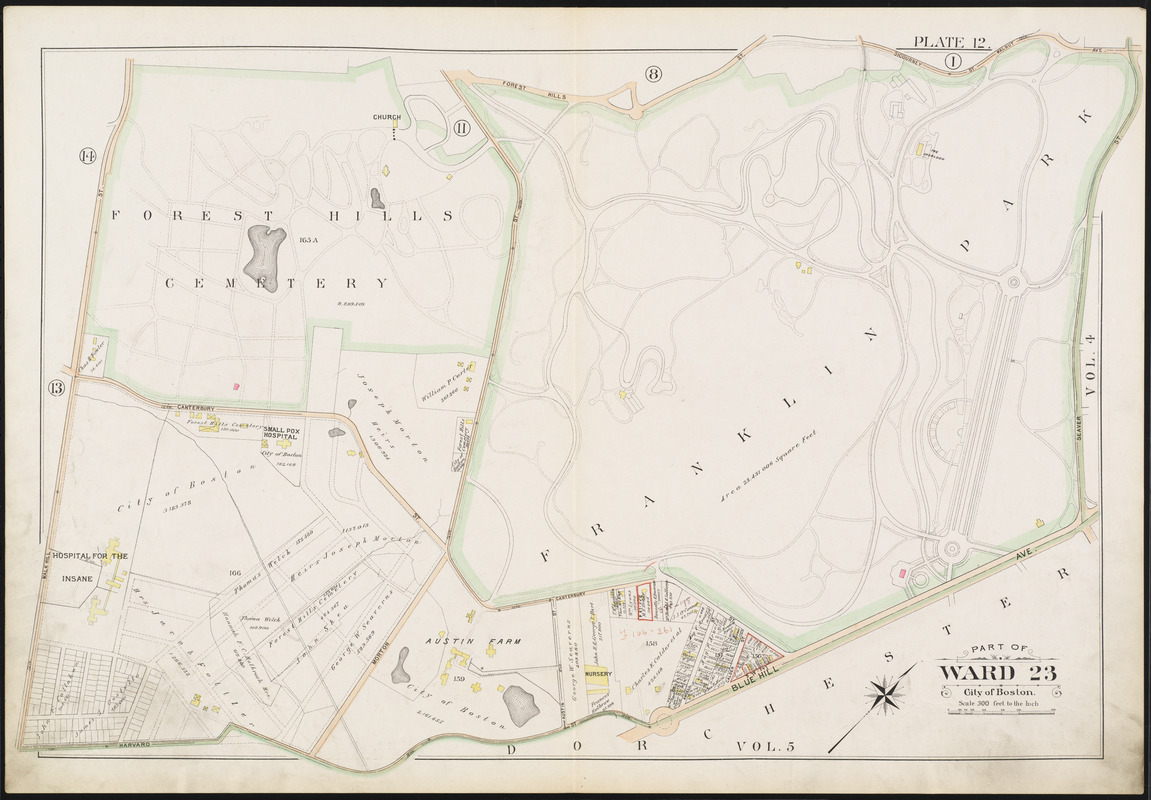

G. W. Bromley & Co.

“Part of Ward 23, City of Boston,” plate 12 in Atlas of the City of Boston, Vol. 6, West Roxbury, 2nd ed.

1896.

Just east of the Arnold Arboretum is Franklin Park, a 485-acre expanse that became part of the park system in 1885. Envisioned by Frederick Law Olmsted as a restful space for Bostonians to recuperate from the stresses of city life, Franklin Park was the place where nature and health met.As this 1896 map illustrates, the park was designed to appeal to a diverse community with designated spaces for quiet repose, as well as those for more invigorating activities such as athletics. However, at the request of citizens, this quiet country park eventually included more stimulating forms of entertainment.

Charles H. Woodbury

Boston Park Guide

1896.

Courtesy Print Department.

By 1896 the public park system in Boston was well established, and the Emerald Necklace was complete. That year the Metropolitan Park Commission published an illustrated guide documenting the park system of greater Boston. This poster created by local artist Charles Woodbury served as an advertisement for the Boston Park Guide. Woodbury, an MIT educated artist, advocated the importance of commercial posters as serious works of art and executed this colorful print as a testament to that belief. A fashionable woman and child stroll leisurely through the park in this simple, yet effective advertisement.

6. Copley Square

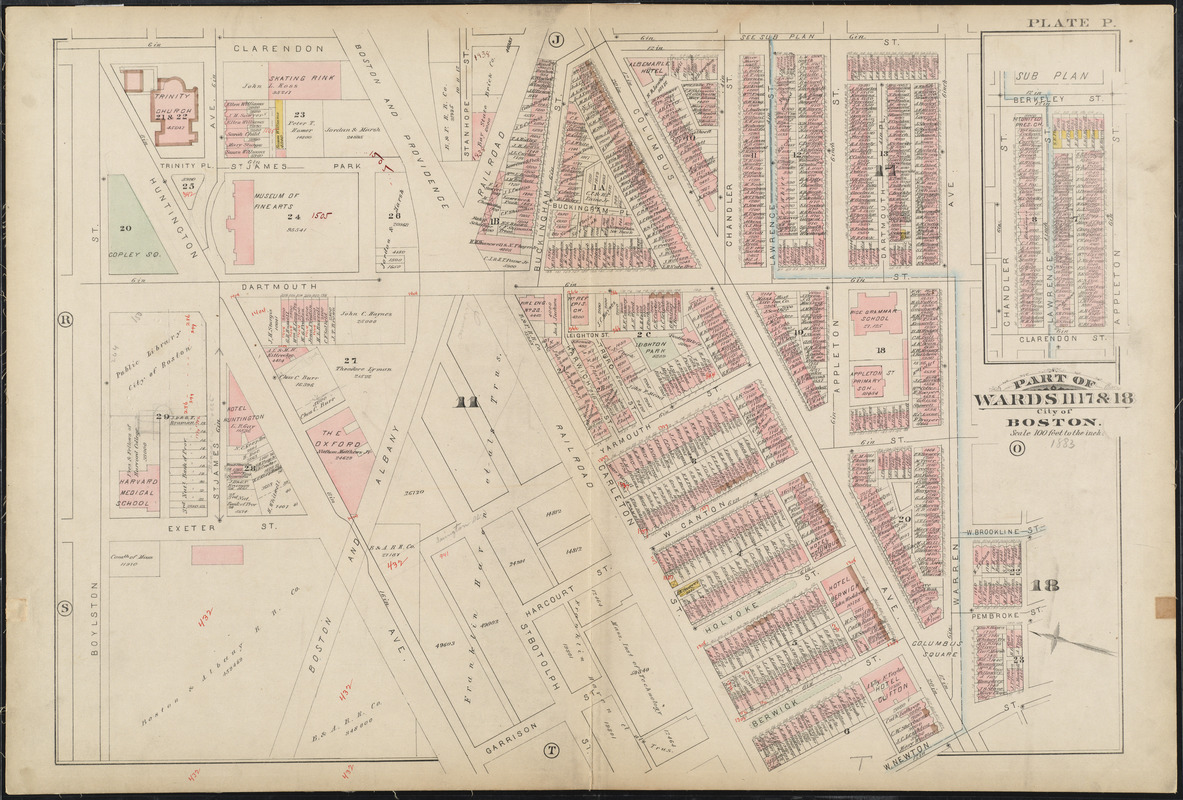

G. W. Bromley & Co.

“Part of Wards 11, 17 & 18,” plate P from Atlas of the City of Boston, Vol. 1, City Proper

1883.

As seen in this 1883 map, Copley Square was once a large triangle. The unique shape of the Square was a result of its location at the junction of the older South End’s and the newer Back Bay’s street grids. Huntington Avenue met Boylston Street at a 45 degree angle, creating a number of triangular spaces in the region. Traffic passed through the square on Huntington Avenue until the late 1960s; however, in the 1980s the area was redesigned to appear as it does today, complete with a large green space for all to enjoy.

Copley Square

1909.

Courtesy Print Department.

Designated as Copley Square in 1883, this open space named for colonial artist John Singleton Copley has always served as a gathering place for locals and visitors alike. However, the square looked much different in the early 20th century than it does today. As portrayed in this 1909 panoramic photograph, the area was once a large triangle, with Huntington Avenue cutting completely across the square to Boylston Street. Taken from the corner of Boylston and Clarendon Streets, this photograph documents the buildings that once stood in “Art Square,” including the S.S. Pierce Building and the Museum of Fine Arts.

Louis H. Ruyl

Public Library – Copley Sq.

1908.

Courtesy Print Department.

American etcher and illustrator Louis Ruyl captured this scene of a bustling Copley Square from the steps of Trinity Church, as pedestrians, trolleys, and cars travel through the busy square in this 1908 drawing. The Boston Public Library had been in operation at this location for sixteen years, and with the Museum of Fine Arts adjacent to the library, the area was also known as “Art Square.” With its many cultural institutions, Back Bay, and Copley Square in particular, became the artistic and intellectual hub of the city in the Gilded Age.

Bibliography

Billington, Ray Allen. The Protestant Crusade 1800-1860: A Study of the Origins of American Nativism. New York : Macmillan, 1938.

Broun, Elizabeth. “Childe Hassam’s America.” American Art., Vol. 13, No. 3 (Autumn 1999), pp. 32-57.

Novels Published in the Gilded Age, or about the Gilded Age

Credits

Stephanie Cyr

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center Staff

Alison Cody, Development and Program Manager

Lauren Chen, Cataloger

Stephanie Cyr, Senior Cataloger

Ronald Grim, Curator of Maps

Janet Spitz, Executive Director

Evan Thornberry, Reference and

Preservation Librarian

Catherine Wood, Office Manager

BPL Research Assistance

John Devine, Government Documents Department

Patricia Feeley, Social Sciences Department

Charlotte Kolczynski, Music Department

Evelyn Lannon, Fine Arts Department

Karen Shafts, Print Department

Stuart Walker, Rare Books and Manuscripts Department

Graphic Design and Production

One2tree

The Market King

Framing and Matting

Andrew Leonard

Digital and Web Services

Tom Blake

Bahadir Kavlakli

Lending Institutions

Boston Public Library Print Department

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Press

Boston in the Gilded Age: Mapping Public Places

The Back Bay Sun, January 29, 2013

Cheap Boston Museums: Free and Discounted Museums in Boston

BostonInno, January 17, 2013

Boston in the Gilded Age: Mapping Public Places

Boston Globe, November 26, 2012

New Exhibition Opens at the BPL’s Norman B. Leventhal Map Center

Press Release, November 9, 2012