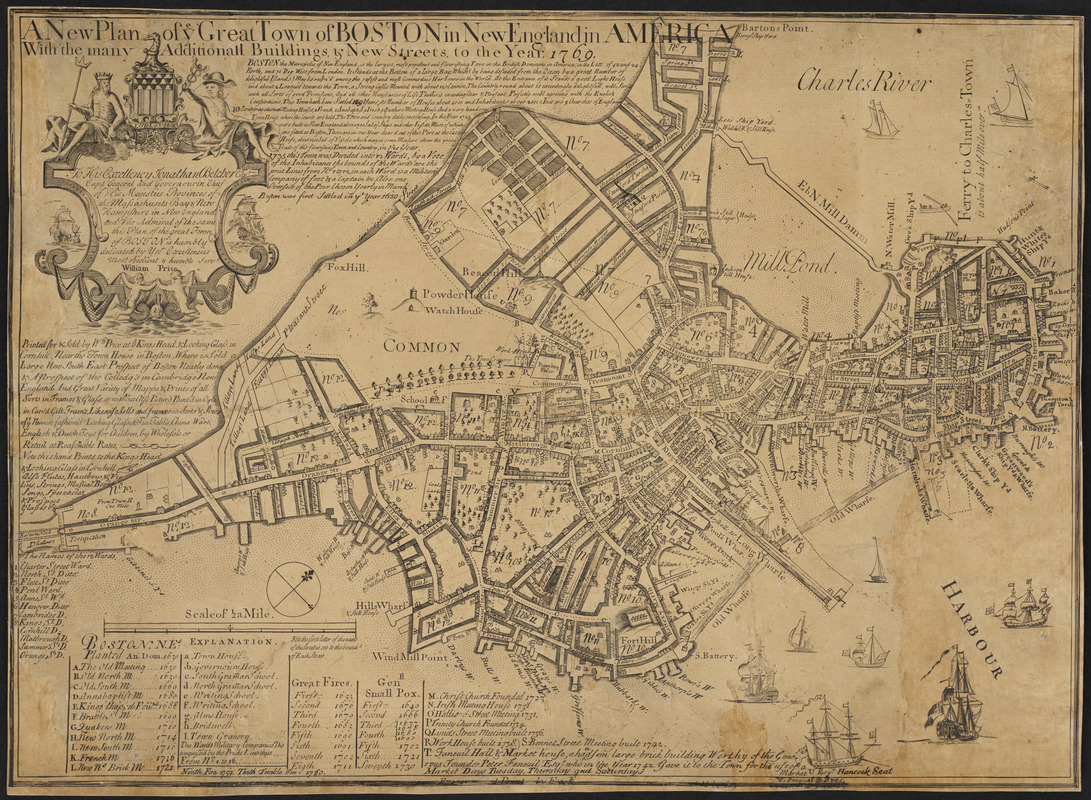

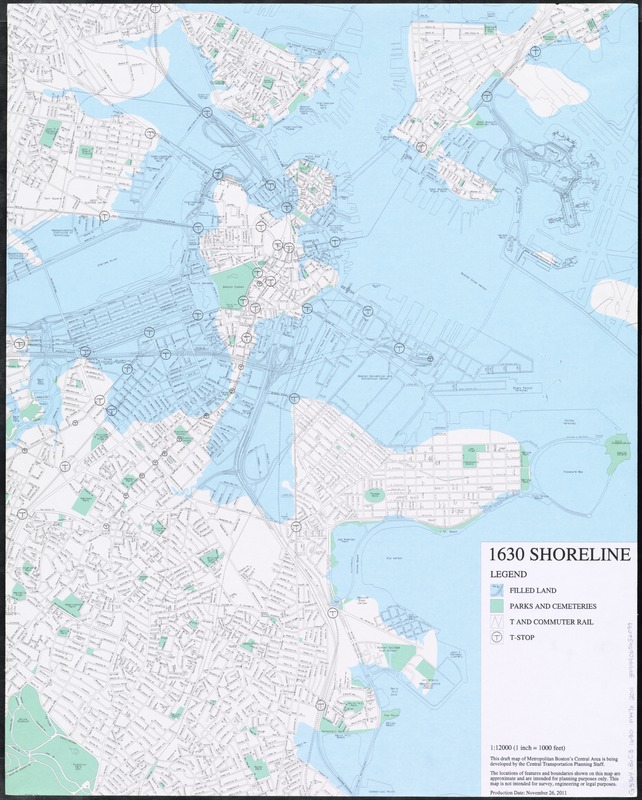

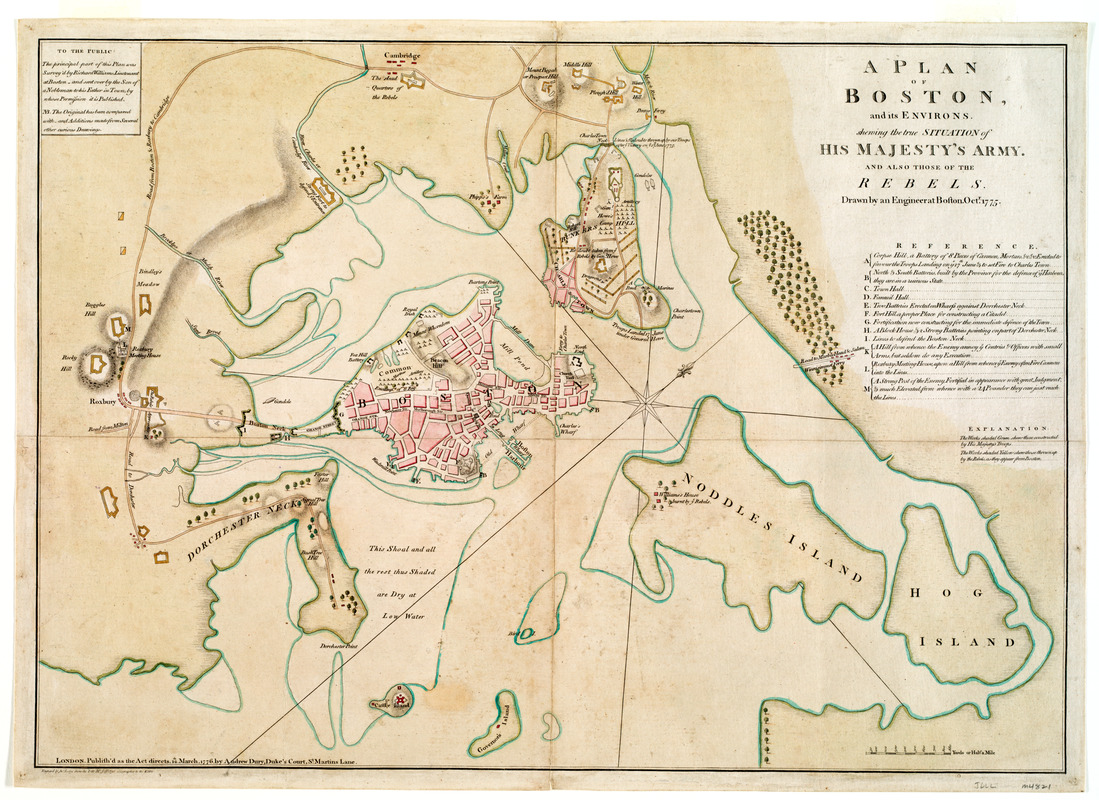

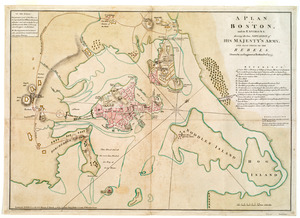

Colonial Boston was a flourishing city of 20,000 by the 1760s. The maps in this set depict its topography with hills, harbors, and narrow attachment to the mainland; its streets, structures and wharves; key sites associated with commerce, government and gatherings of all kinds. And then, of course, these maps document its role as the center of revolution, both before and after the fateful date of April 19, 1775, when the “shot heard round the world” signaled the beginning of the American Revolution.

Boston became a center of opposition to British policies, which were intended to raise money to pay for troops stationed in the colonies during the French and Indian War between 1756 and 1763. In 1765, when officials tried to enforce the Stamp Act that had been passed by Parliament, colonists responded with actions which ranged from carefully framed arguments circulated throughout the towns and colonies in pamphlets, newspapers and letters to public demonstrations and riots. The Sons of Liberty ensured that “no taxation without representation” became a rallying cry. Legal debates were supplemented by economic measures such as refusal to consume British goods or goods coming on British ships. Customs commissioners and others collecting duties and taxes were intimidated in a climate of increasing outrage and threat.

The potential for violence escalated when British troops arrived in this volatile city in 1768, a measure meant to suppress the protests and restore order. The stationing of 4,000 soldiers in a city of 20,000 people squeezed onto a narrow peninsula had the opposite effect. The Boston Massacre two years later was a tragic consequence.

Committees of Correspondence, essentially emergency governments formed by Patriot leaders in the colonies to coordinate information and actions, contributed to coordinated resistance throughout Massachusetts and the other colonies. The Boston Tea Party in 1773 was another tipping point in the mounting tensions. By 1774, the countryside around occupied Boston was in rebellion. Towns began sending their tax money to the outlawed government—the Provincial Congress—and raising Minute companies to defend their communities and their “charter rights”. The Provincial Congress ordered that military supplies be stockpiled in Concord, twenty miles west of Boston.

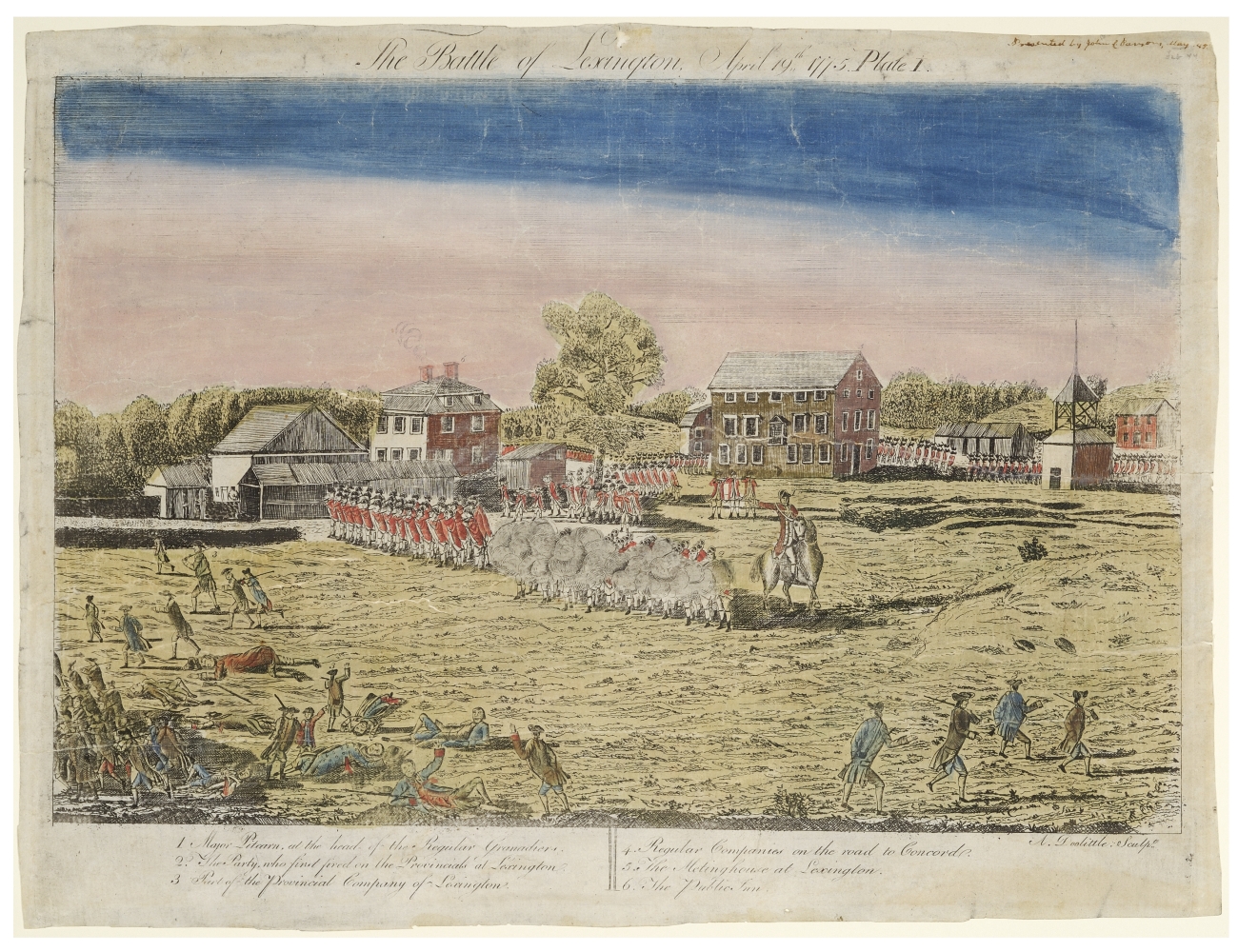

And on the night of April 18, 1775, the commander of all British forces in North America, General Gage, issued the order to destroy those supplies. The colonists had long expected and planned for this move. But did anyone foresee the bloody, calamitous events soon to come, and the long war for independence that followed?

Boston became a center of opposition to British policies, which were intended to raise money to pay for troops stationed in the colonies during the French and Indian War between 1756 and 1763. In 1765, when officials tried to enforce the Stamp Act that had been passed by Parliament, colonists responded with actions which ranged from carefully framed arguments circulated throughout the towns and colonies in pamphlets, newspapers and letters to public demonstrations and riots. The Sons of Liberty ensured that “no taxation without representation” became a rallying cry. Legal debates were supplemented by economic measures such as refusal to consume British goods or goods coming on British ships. Customs commissioners and others collecting duties and taxes were intimidated in a climate of increasing outrage and threat.

The potential for violence escalated when British troops arrived in this volatile city in 1768, a measure meant to suppress the protests and restore order. The stationing of 4,000 soldiers in a city of 20,000 people squeezed onto a narrow peninsula had the opposite effect. The Boston Massacre two years later was a tragic consequence.

Committees of Correspondence, essentially emergency governments formed by Patriot leaders in the colonies to coordinate information and actions, contributed to coordinated resistance throughout Massachusetts and the other colonies. The Boston Tea Party in 1773 was another tipping point in the mounting tensions. By 1774, the countryside around occupied Boston was in rebellion. Towns began sending their tax money to the outlawed government—the Provincial Congress—and raising Minute companies to defend their communities and their “charter rights”. The Provincial Congress ordered that military supplies be stockpiled in Concord, twenty miles west of Boston.

And on the night of April 18, 1775, the commander of all British forces in North America, General Gage, issued the order to destroy those supplies. The colonists had long expected and planned for this move. But did anyone foresee the bloody, calamitous events soon to come, and the long war for independence that followed?

![A new plan of ye great town of Boston in New England in America, with the many additionall [sic] buildings, & new streets, to the year, 1769](https://bpldcassets.blob.core.windows.net/derivatives/images/commonwealth:3f462v50z/image_thumbnail_300.jpg)

![A view of part of the town of Boston in New-England and Brittish [sic] ships of war landing their troops! 1768](https://bpldcassets.blob.core.windows.net/derivatives/images/commonwealth:4m90f851p/image_thumbnail_300.jpg)