Introduction

With each election Americans have become accustomed to seeing national maps colored red and blue signifying Republican and Democratic voting patterns. Presenting election results has long intrigued mapmakers as the maps and graphics in this exhibition reveal. Examples range from several early efforts to the most recent campaigns.

The display begins with gerrymandering, 200 years of manipulating political districts for partisan objectives, and includes maps illustrating the extension of the vote to non-property owners, blacks, and women. These issues are represented in many examples that also show the importance of the states as the proxy for the voice of the people they represented. Efforts to legislate behavior, such as prohibition, were another aspect of mapping the political landscape

1. USA, Then and Now

Jean Lattré,

Carte des Etats-Unis

1784.

This is the first map of the new United States issued after the ratification of the Treaty of Paris, formally ending the war with England in 1783. The ship depicted in the cartouche symbolizes the course set by this new independent nation. The distinct delineation of individual state boundaries, however, was an important reminder that the union was composed of individual states, then operating under the Articles of Confederation, and unwilling to cede power to a strong central authority. The map was published in France, America’s primary ally during the Revolution.

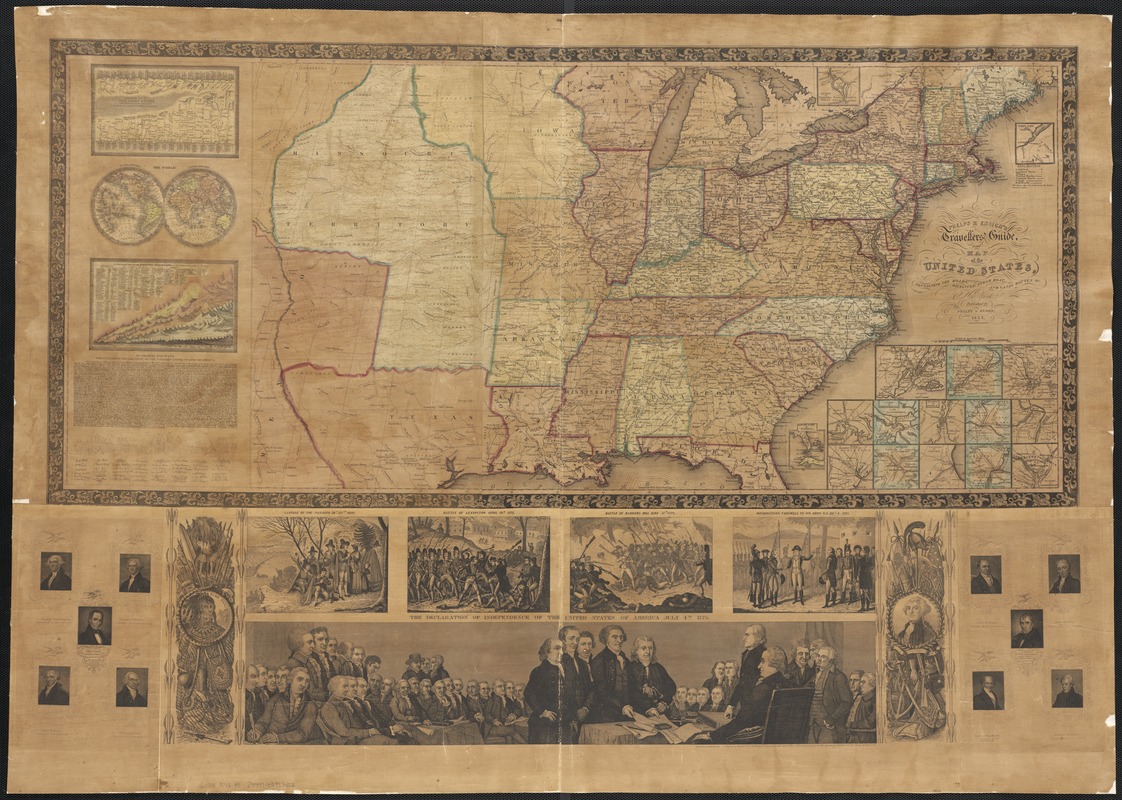

Phelps & Ensign

Map of the United States

1842.

While intended as a traveler’s guide, this large wall map displays a number of patriotic illustrations. Historic moments such as the landing of the Pilgrims, the Battle of Bunker Hill, Washington’s farewell to his troops, and the signing of the Declaration of Independence are highlighted. The full text of this defining document and portraits of the nation’s first ten presidents are included. The map itself provides a snapshot of the nation 50 years after its founding, when the country consisted of 26 states and three territories.

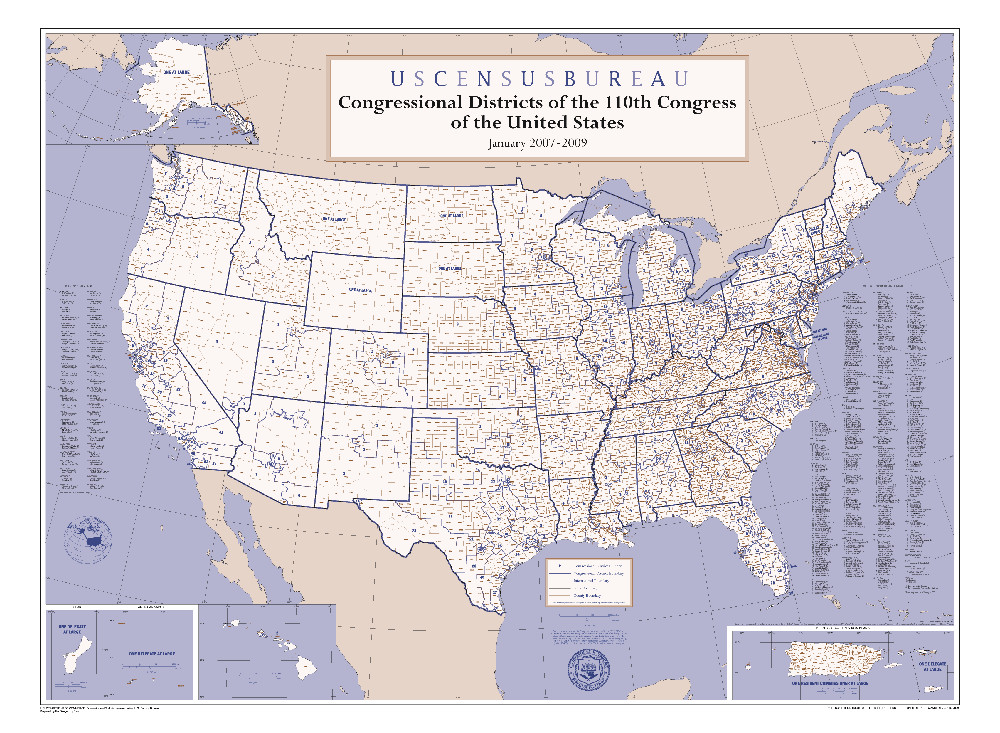

U.S. Census Bureau, Geography Division

Congressional Districts of the 110th Congress of the United States, January 2007-2009

2007.

Citizens of each state in the union are represented in Washington by two senators and proportionately in the House of Representatives according to population. Consequently, the Federal government conducts a census every ten years to determine the number of representatives allotted to each state. This map delineates the boundaries of the Congressional Districts that have been in effect since the 2000 census. Based on the 2010 census, the boundaries are again being redrawn in 17 states (including Massachusetts and Texas) and will be finalized for the Fall 2012 elections.

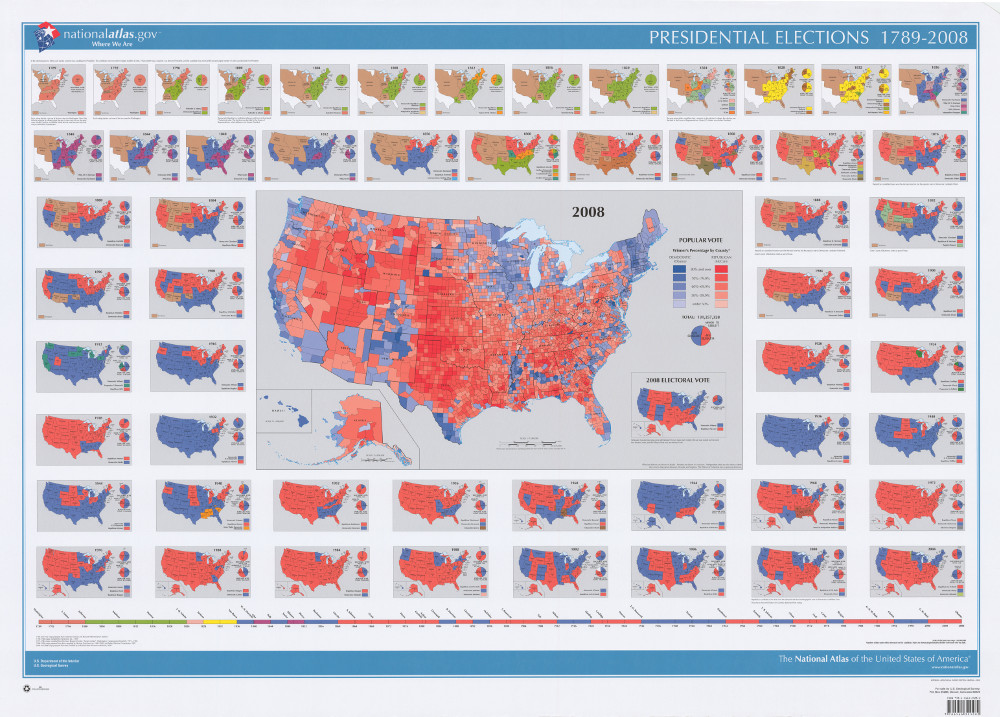

U.S. Geological Survey

The National Atlas of the United States of America: Presidential Elections, 1789-2008

2009.

Image from Iowa Digital Libraries

The results of every presidential election are summarized by state on this comprehensive poster. A large inset map provides more detailed returns for the 2008 contest between John McCain and Barack Obama. The cartographer has provided a county-by-county reporting of this election. Rather than simply seeing each state as supporting a single candidate, the viewer understands the variation within a state. For example, while Obama only won 18 of Pennsylvania’s 67 counties, he carried the heavily populated areas that included Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, thus garnering its 21 electoral votes.

2. From Gerrymander to Bushmander

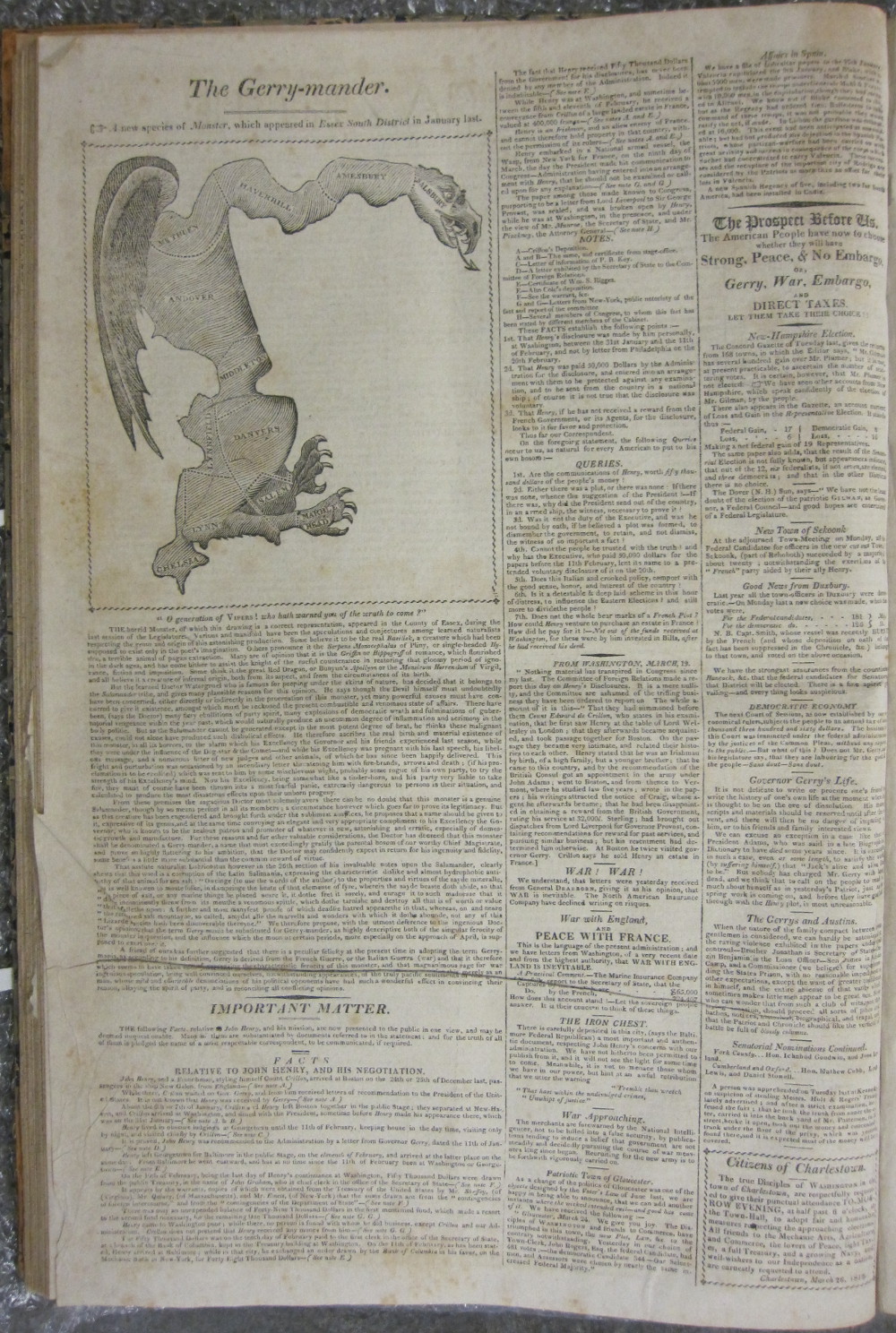

[Elkanah Tisdale]

“The Gerry-mander, a new species of monster, which appeared in Essex South District in January last,” in Boston Gazette

March 26, 1812.

Courtesy American Antiquarian Society.

The concept of “gerrymandering” originated 200 years ago in Massachusetts with the redrawing of state senatorial districts based on the 1810 census. The word first appeared in print in this Boston newspaper. The accompanying cartoon-map characterized the new northwestern district of Essex County as a monster with claws, wings, and dragon head. The term was coined by combining the name of Governor Elbridge Gerry, an advocate of the proposed redistricting plan, with a mythical “salamander” whose shape the district was said to resemble. This word has become a standard term referring to the manipulation of election district boundaries to benefit a specific political party or interest group.

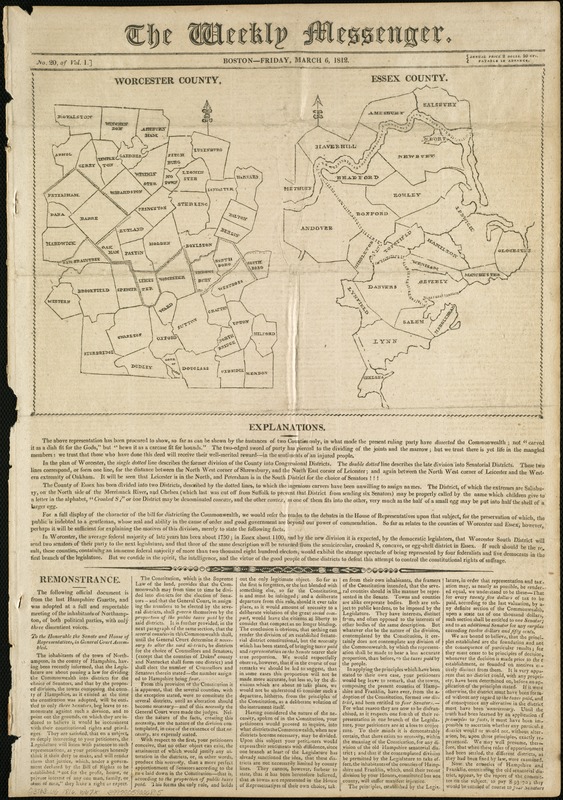

“[Maps of] Worcester County [and] Essex County,“ in Weekly Messenger, vol. 1, no. 20

March 6, 1812.

During the first weeks of March 1812, several Boston newspapers published this map which inspired the creation of the “gerrymander” cartoon. The map illustrates the new senatorial districts in Worcester and Essex Counties. The article explains that these counties had an “immense Federal majority,” but would likely elect four Federalists and five Jeffersonian Democrat-Republicans, the party of Governor Elbridge Gerry. In criticizing this redistricting plan, the influential Federalist newspapers commented that the ruling party carved the Commonwealth, “not … as a dish fit for Gods’ but ‘hewn it as a carcase fit for hounds.’”

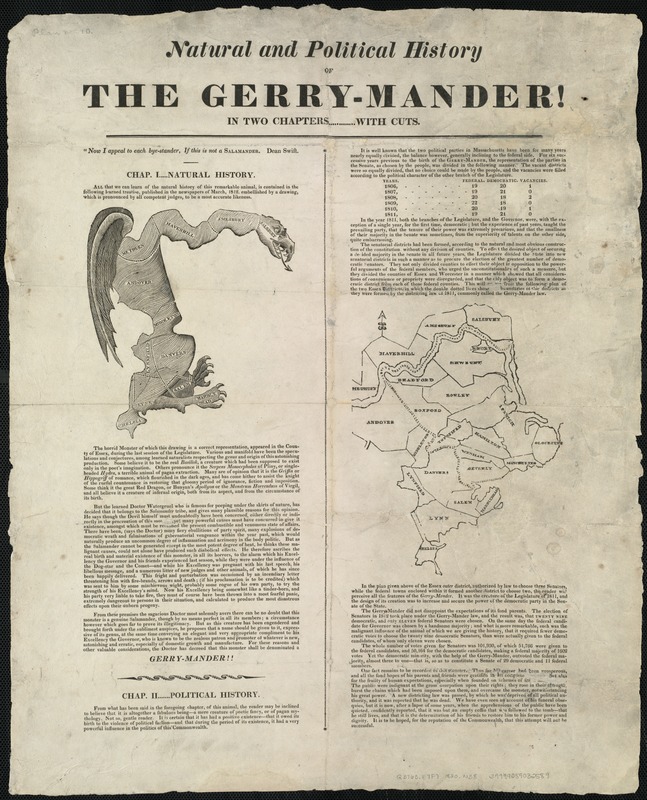

Natural and Political History of the Gerry-mander!

[ca. 1820].

Published about 1820, this broadside reprinted the original 1812 newspaper article and cartoon illustrating the first use of the term “Gerry-mander.” It also included a new essay entitled “Political History,” that explained its origins in the Massachusetts’ 1812 senate redistricting plan and confirmed that the results of the subsequent election favored the Democrat-Republicans as anticipated. Although the editors called for the death of the “Gerry-mander,” the practice survived. Two hundred years later, it remains a powerful part of our political lexicon as both a concept and a partisan strategy employed on both sides of the aisle.

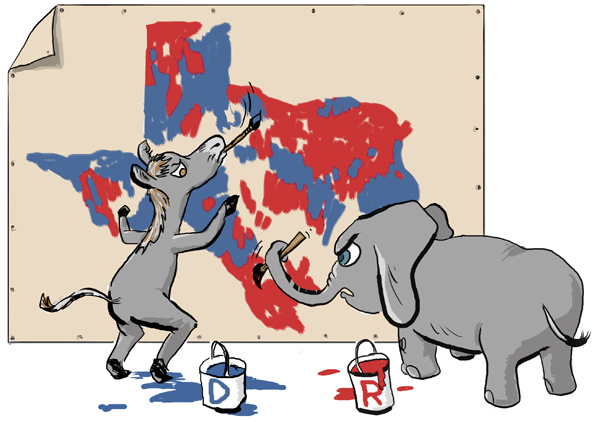

José-Luis Olivares

“Redistricting Texas Style”

Published online by University of Texas at Austin, Liberal Arts Instructional Technology Services, January 2004.

Courtesy of the artist.

The 2004 article “Redistricting Texas Style” explored years of creating partisan-drawn Congressional districts. As the accompanying cartoon suggests, both the elephant and donkey seek to influence the process, making sure to ‘color’ the state to its own advantage. Their determined looks and ‘slap dash’ approach indicate the nature of the process—acquire as much territory as possible with little regard for the resulting logic of the districts drawn. The artist, José-Luis Olivares from Medford, MA, captures the circus-like nature of the proceedings that seem to characterize the process of repeatedly re-arranging the political landscape.

U.S. Geological Survey

The National Atlas of the United States of America: Congressional Districts, 112th Congress (January 2011 – January 2013), Texas

2011.

Based on the 2010 census, Texas gained four electoral votes, necessitating a redrawing of its Congressional districts. This process has been fraught with partisanship and rancor at the state and Federal levels, prompting litigation, and intervention by state and Federal courts. In addition to concerns of apportionment and minority rights, is the underlying issue of a state government’s right to create its own Congressional districts while also being in compliance with Federal mandates to guarantee fairness, as outlined in the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The resulting districts perpetuate 200 years of a gerrymandered political landscape.

3. Mapping Massachusetts Congressional Districts

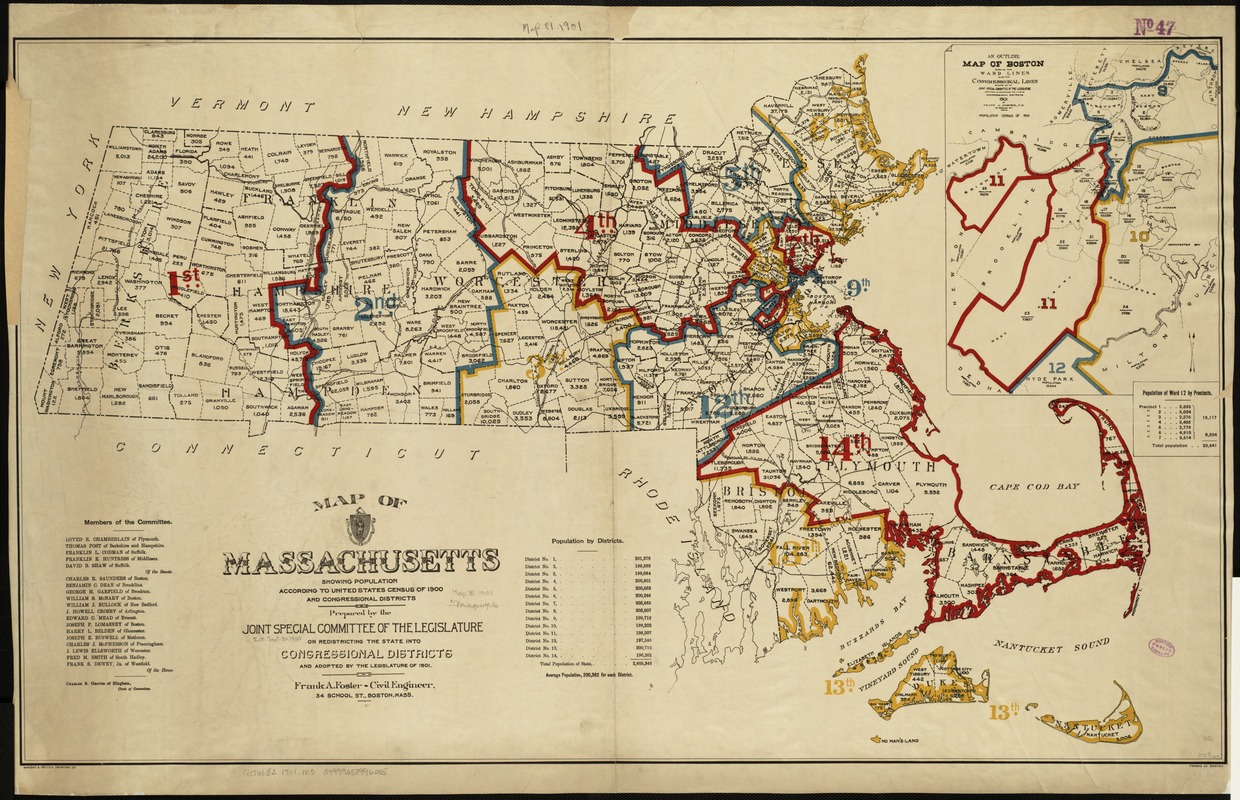

Frank A. Foster

Map of Massachusetts Showing Population According to the United States Congress of 1900 and Congressional Districts

1901.

In 1900, Massachusetts had 13 Congressional Districts. After the 1900 census, it needed to add another and this map shows the new boundaries. Districts were drawn to encompass adjacent areas when possible, but as the site of the original gerrymander, eastern Massachusetts has long had oddly shaped voting districts. The expansion of Boston in the late 19th century to incorporate Allston and Brighton also resulted in non-adjacent areas being included in the same district as the inset map of the 11th indicates. Population figures for towns within districts help viewers understand the link between geographic area and population density.

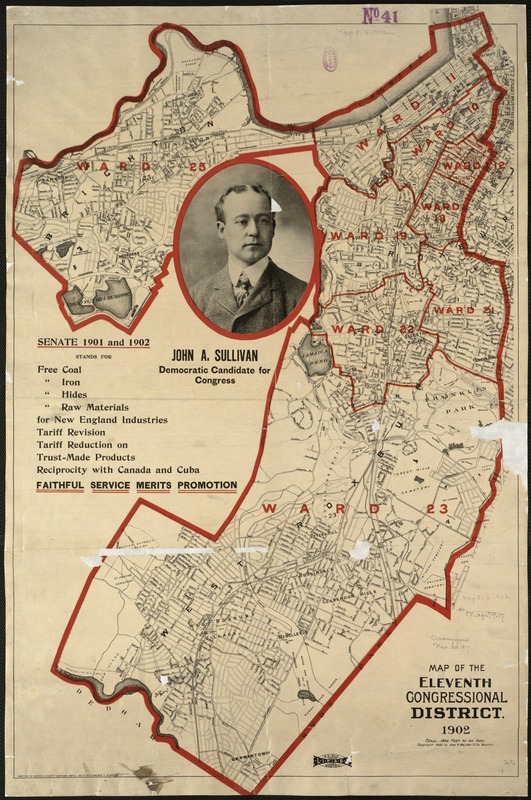

Geo. H. Walker & Co.

Map of the Eleventh Congressional District, 1902

1902.

John Sullivan, Democratic candidate for the Massachusetts 11th, used this map as the basis for his campaign poster. Illustrating the local nature of city politics, it highlighted the wards within the district, showing the literal political landscape. His campaign slogans echo key urban, industrial themes of the era—encouraging business while supporting workers who suffered from higher prices caused by increased tariffs that protected domestic industry. Implicit in his message were the realities of city politics, as promised in his slogan, “Faithful Service Merits Promotion.” He represented the 11th District for two terms in Congress.

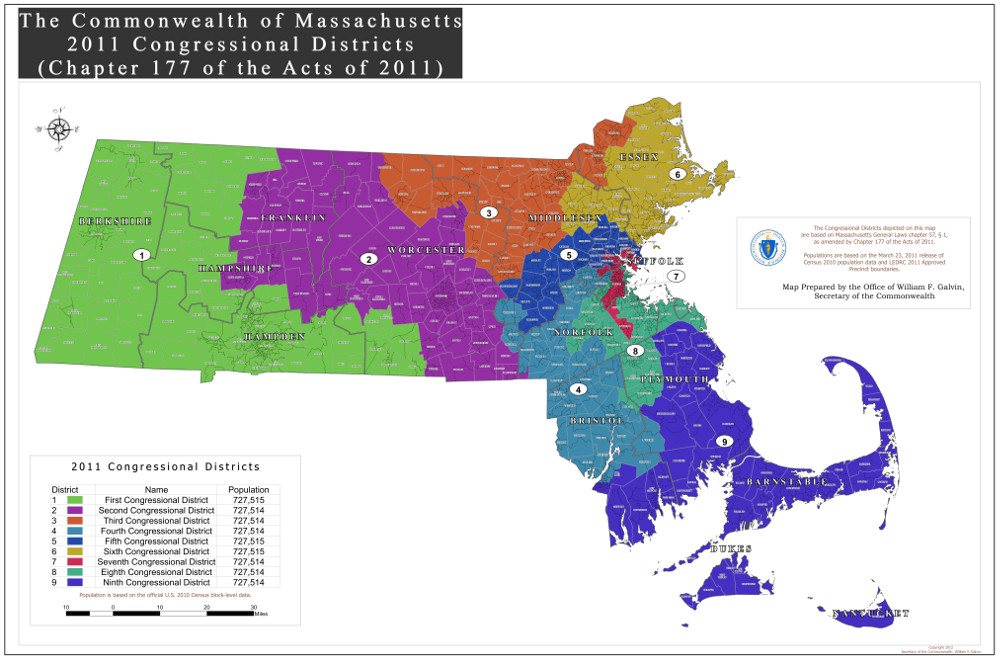

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 2011 Congressional Districts, Chapter 177 of the Acts of 2011

2012.

As a result of the 2010 census, Massachusetts lost one of its electoral votes and was forced to eliminate a Congressional district for the first time since 1980. The resulting redistricting led to this new map. The state has long had non-contiguous districts, a process which has sought to balance geographic proximity with the rights of minority voters. The new districts are more geographically compact, although vestiges of odd formations persist, particularly in the 4th and 8th districts. All current Congressional representatives found their incumbency challenged to some extent in this new landscape.

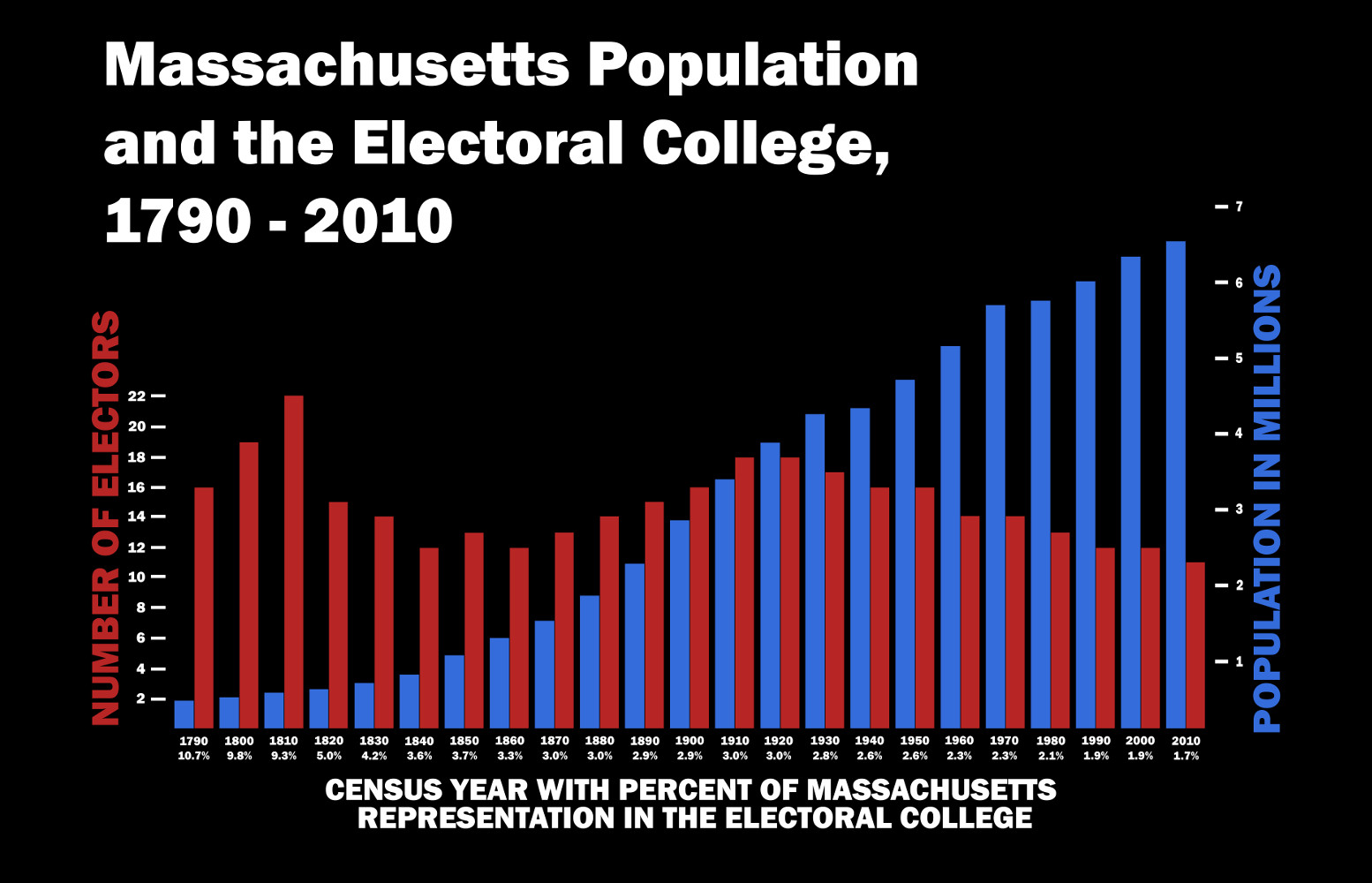

Evan Thornberry

Massachusetts Population and the Electoral College, 1790 to 2010

2012.

As one of the original 13 states, Massachusetts has participated in every Presidential election. It has had anywhere from 10 to 22 electoral votes. Yet its overall influence has declined over the course of time. Originally 10 per cent of the Electoral College, its proportional power has remained at approximately 2 per cent since Congress capped the total number of representatives at 435 in 1928. As its population stabilized or dropped relative to other states, Massachusetts’ power on the national stage has declined as this bar graph indicates.

4. Mapping Presidential Election Results

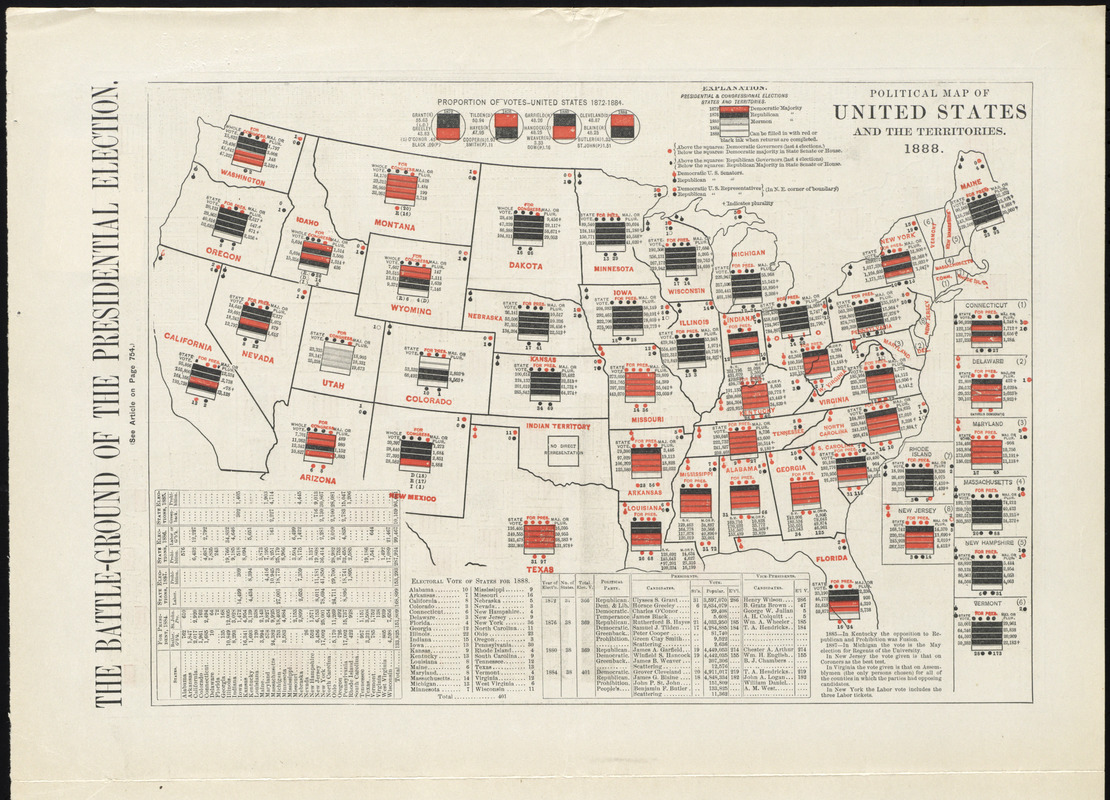

“The Battle-Ground of the Presidential Election. Political Map of the United States and the Territories, 1888,” from Harper’s Weekly

October 6, 1888.

Since the late 19th century, map makers have experimented with various graphic techniques for displaying Presidential election results. One of the earliest and most complex attempts was published in anticipation of the 1888 election between Republican Benjamin Harrison and Democrat Grover Cleveland. Each state was overlaid by five rectangular bars. The first four bars were colored either black for a Republican majority or red for a Democratic majority, signifying the results of the four previous elections. The fifth bar was left blank for recording the 1888 results. A series of colored dots also signified the party affiliation of governors, senators, and representatives.

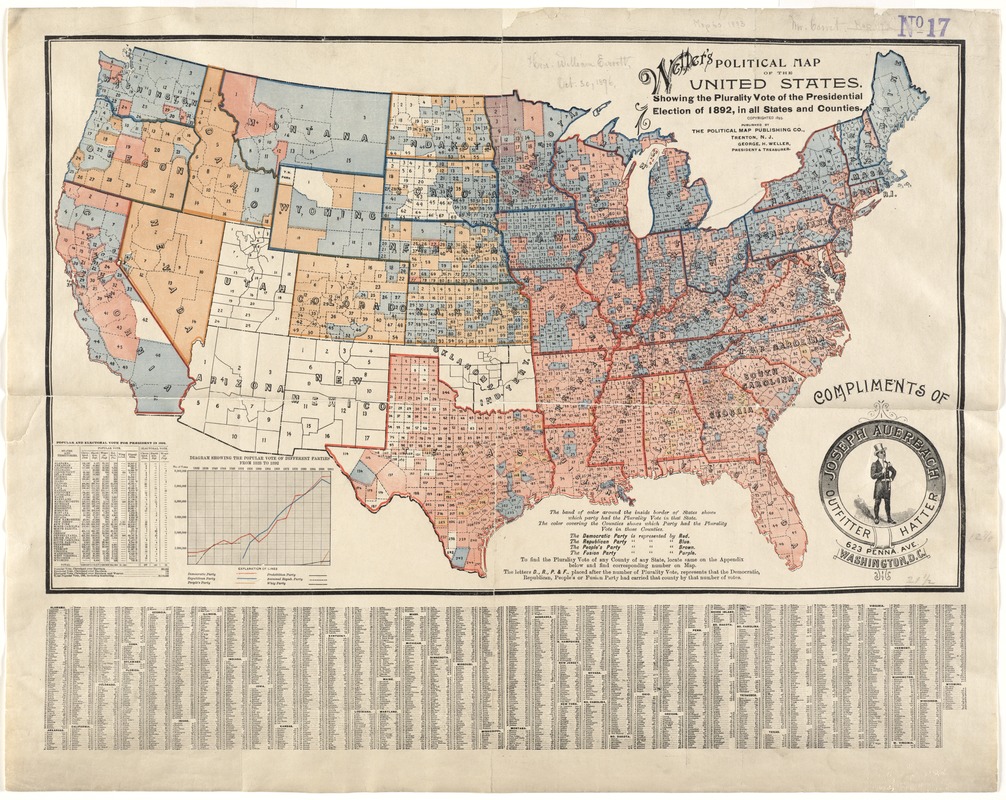

George H. Weller

Weller’s Political Map of the United States Showing the Plurality Vote of the Presidential Election of 1892 in all States and Counties

[1893?]

Prepared after the 1892 election, which pitted Republican Benjamin Harrison against Democrat Grover Cleveland for a second time, this map displayed the pluralities or majorities at both the county and state levels. Counties were shaded red, blue, or brown to signify Democratic, Republican, or Peoples party majorities. State boundaries were highlighted with the appropriate party color to indicate majorities for the entire state. In contrast to the 1888 election when Harrison won the electoral vote but not the popular vote, Cleveland won both the electoral and popular vote in 1892.

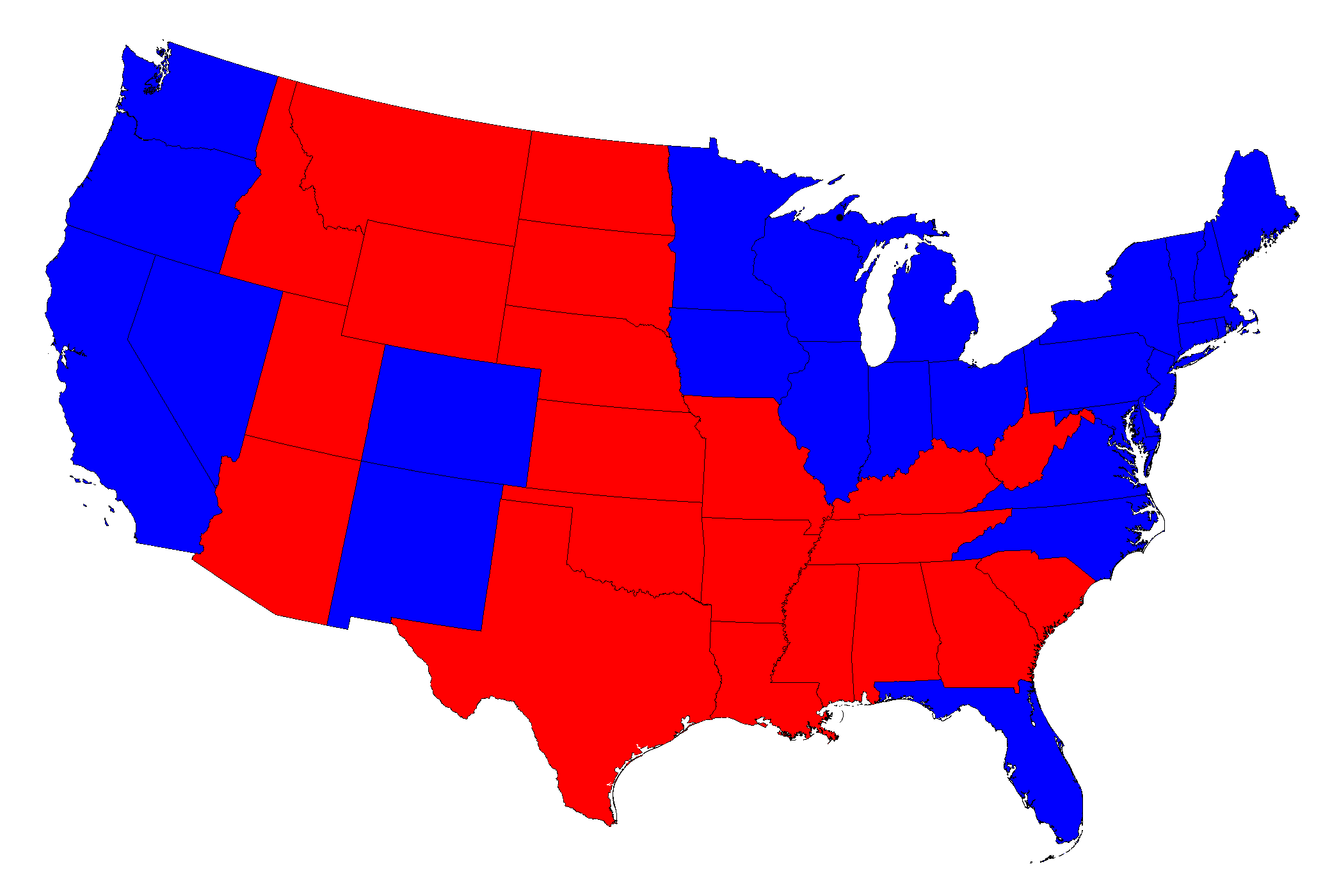

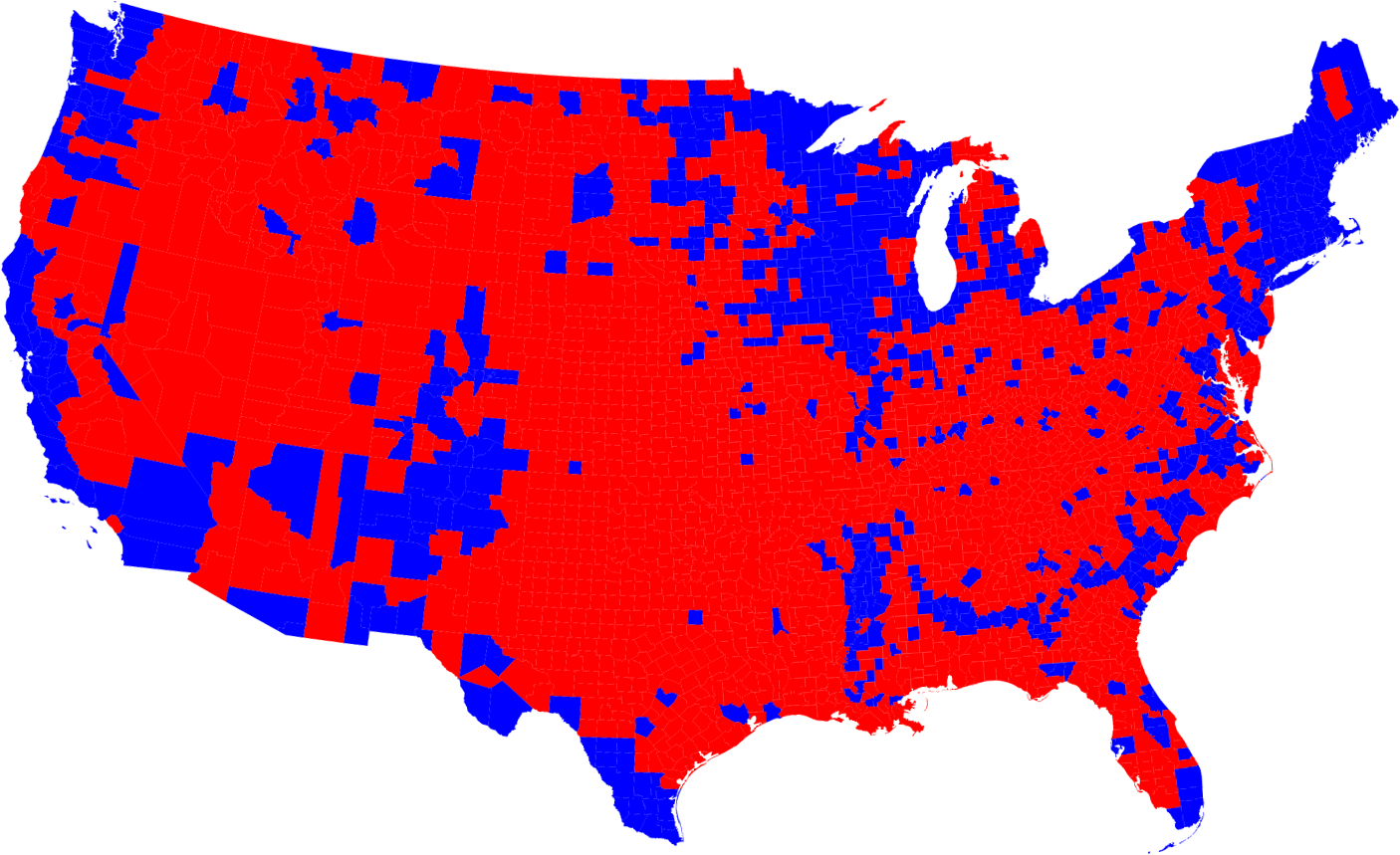

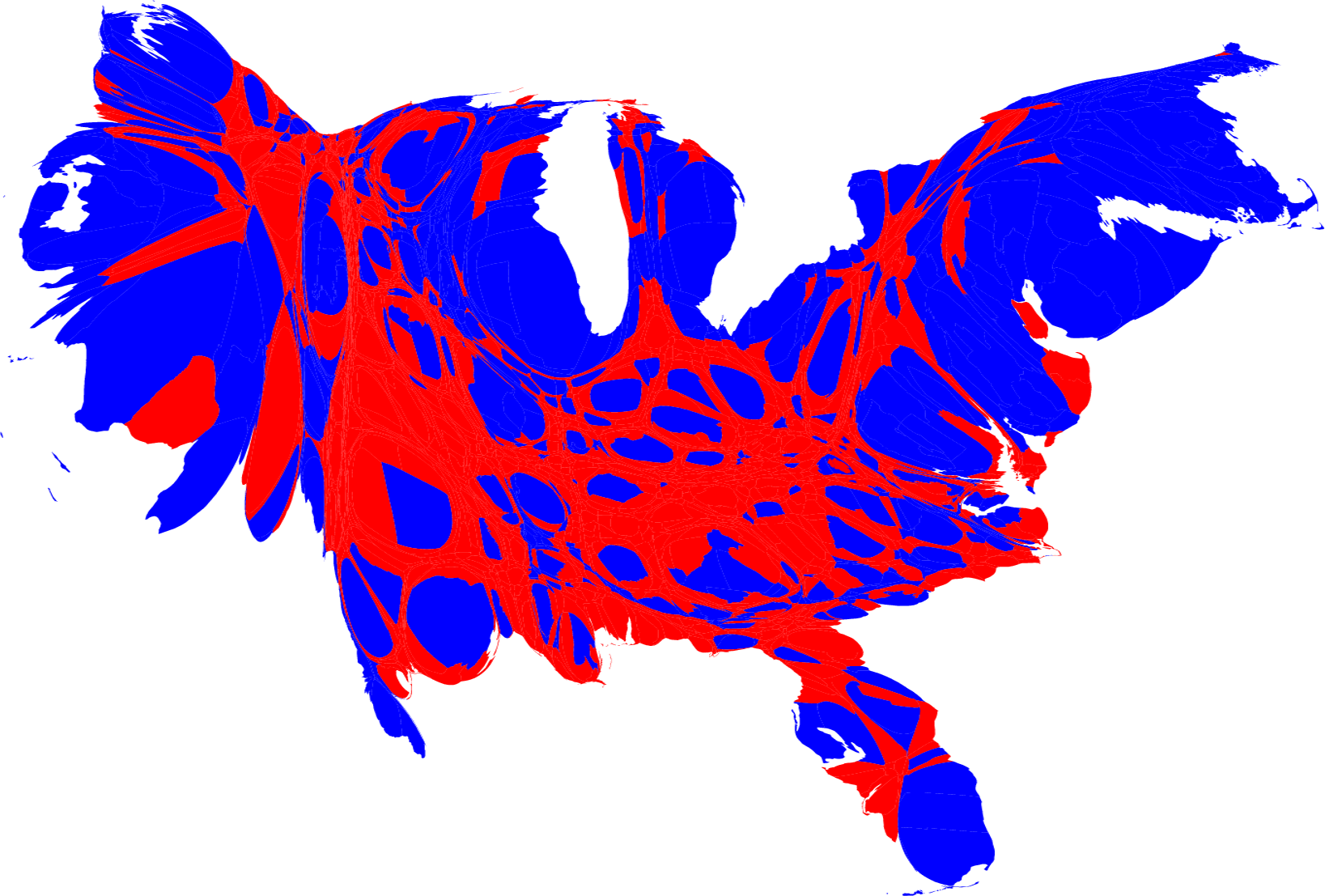

Mark Newman

[Election Results Based on State and County Maps] from Maps of the 2008 US Presidential Results

Published online.

Courtesy of the author.

The results for the 2008 Presidential election are shown on these standard state and county maps of the nation that portray geographic areas based on their acreage. This practice creates a false visual impression in Presidential elections where population, not acreage, determines victory. Therefore, a large physical state with a small population has little overall influence in a general election. These maps, known as choropleth maps, give the mistaken notion that Republican John McCain won the election because there is more red than blue on both maps. In actuality, Democratic Barack Obama won the election capturing over 67 percent of the Electoral College vote.

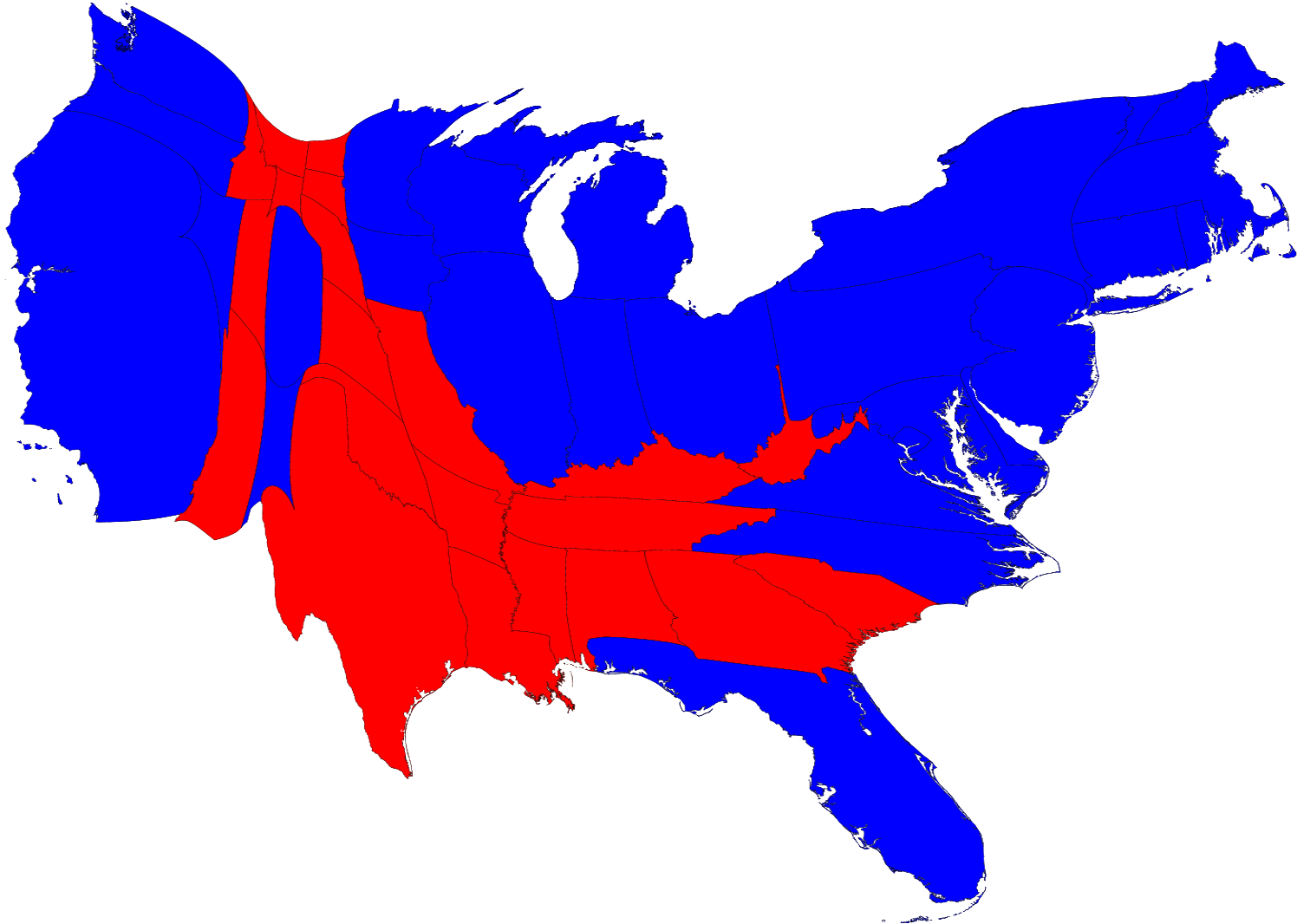

Mark Newman

[Election Results Based on State and County Cartograms] from Maps of the 2008 US Presidential Results

Published online.

Courtesy of the author.

Standard state and county maps show acreage but fail to note population distribution. In reporting the results of a Presidential election, these maps misrepresent areas of low and high population density. By using a cartogram, in which the map is rescaled to each state’s or county’s population rather than its acreage, a different impression is created. Now that the states and counties have been stretched and squeezed, there is clearly more blue than red.

5. States’ Rights and Agendas

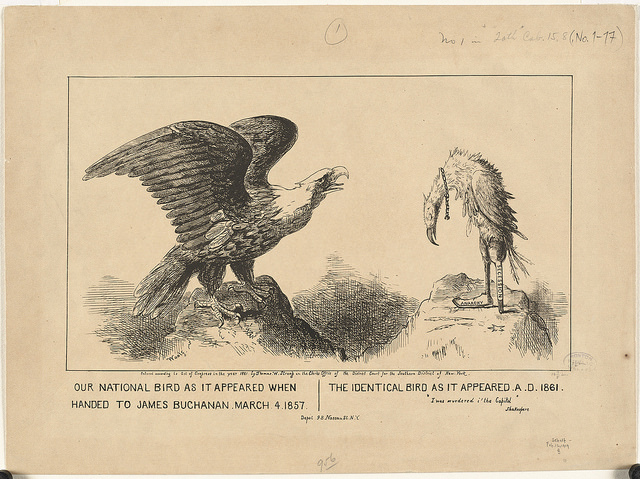

Thomas Strong

Our national bird as it appeared when handed to James Buchanan, March 4, 1857. The identical bird as it appeared A. D. 1861

1861.

Courtesy Print Department.

The iconic national bird, representing the Union, is strong and healthy at the beginning of Democrat James Buchanan’s administration, but by the time Republican Abraham Lincoln assumed the Presidency, it is gaunt and emaciated reflecting the secession of 11 southern states from the Union. This political cartoon highlights the rising tensions over states’ rights during the antebellum period and the ultimate dissolution of the Union in 1861. The fact that Buchanan’s administration was riddled with corruption and charges of bribery and graft, only worsened the toll that years fighting over slavery and states’ rights had taken on the nation’s vitality.

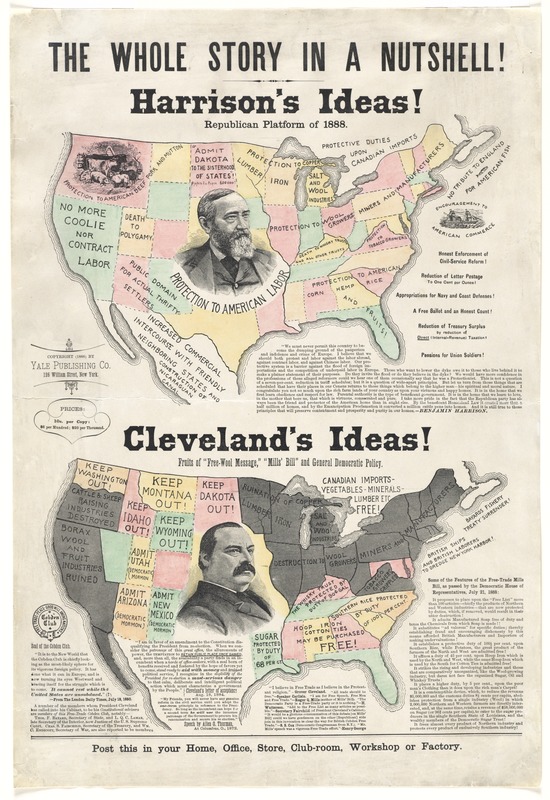

Republican Party

The Whole Story in a Nutshell!

1888.

Major differences between incumbent Democrat Grover Cleveland and his Republican rival Benjamin Harrison during the 1888 Presidential campaign are emphasized on this campaign poster. During this era of rapid industrialization, Harrison promoted himself as the candidate best suited to national and international concerns while still being aware of important issues at the state level. The map imagery highlights Harrison’s expansionist position while underscoring Cleveland’s limited appeal, particularly in states colored gray. The fact that Harrison’s party and administration worked against organized labor did not prevent him from making it a central claim in his campaign poster.

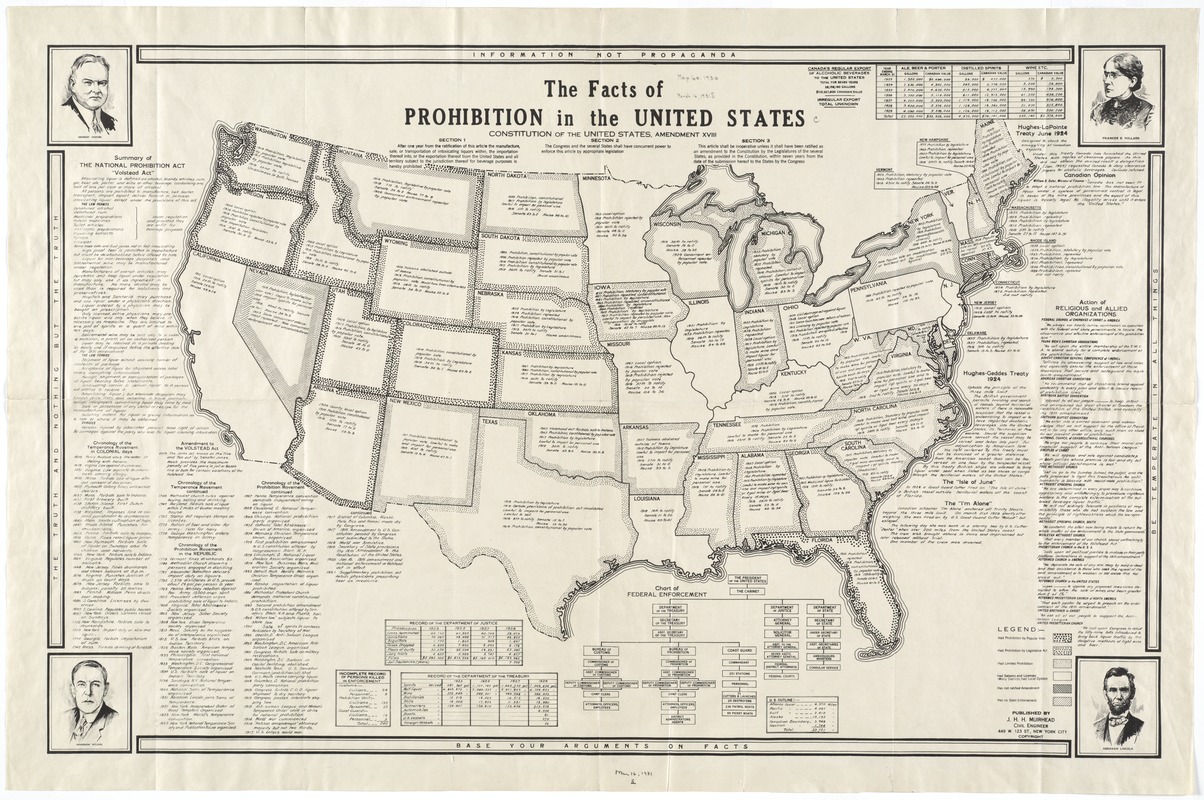

James Herbert Hawksworth Muirhead

The Facts of Prohibition in the United States

[ca. 1924]

The notion of legislating certain behaviors has long divided America. Restricting the sale and consumption of alcohol seems morally justified to some and outlandish to others. Certain forces converged to fight for Prohibition in the early 20th century. They understood that residents in large urban areas would work against them and as this map indicates, state by state they would use a Constitutional amendment to bring out the necessary change to the American landscape, appreciating that even within states, there would be local sensibilities about which strategies to pursue. The story of this battle surrounds the map.

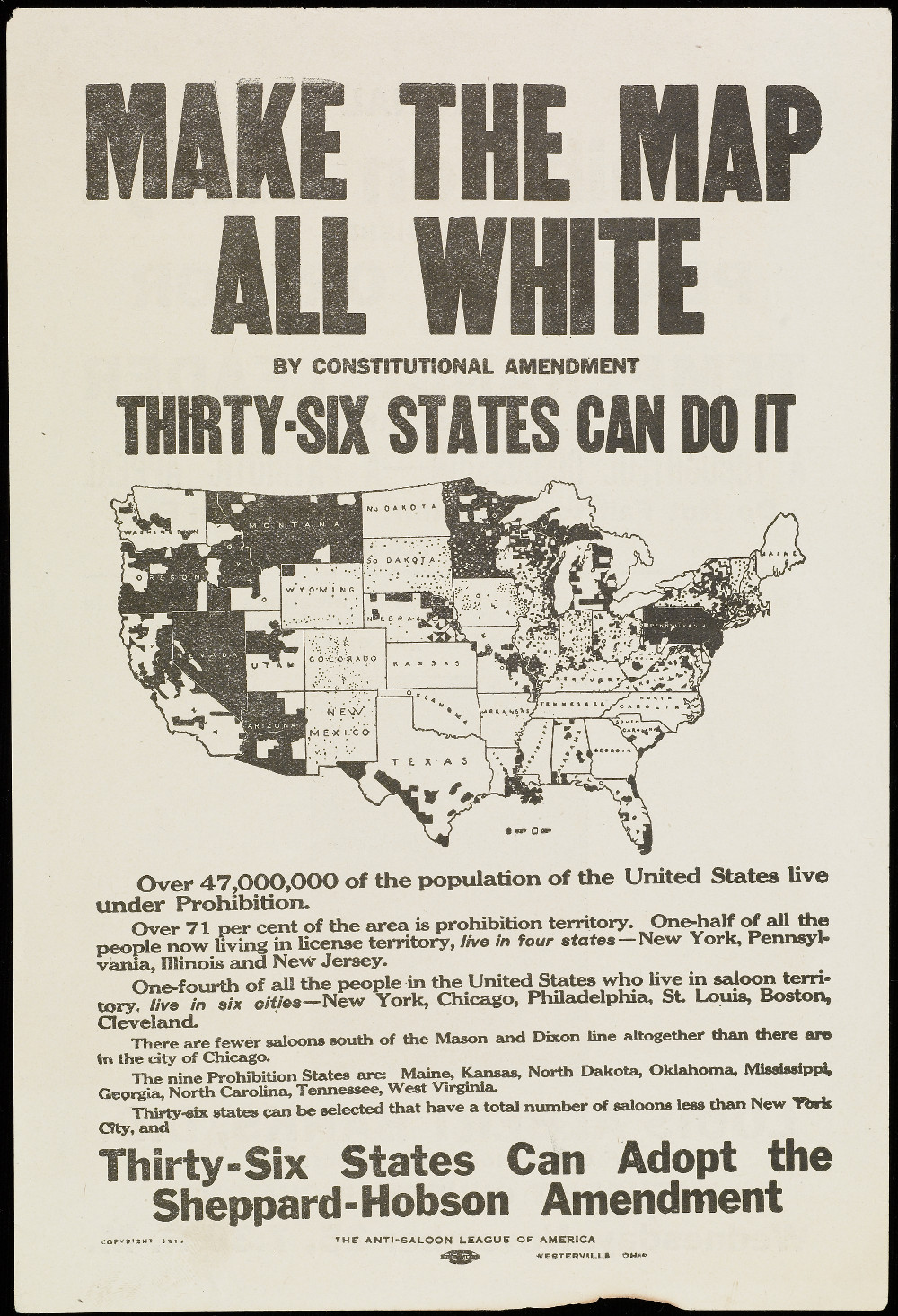

Make the Map All White by Constitutional Amendment

1914.

Courtesy University of Virginia, Special Collections.

The battle for prohibiting the sale and consumption of alcohol had its roots in the 19th century temperance movement. By the 20th century, it had been joined by the reform spirit of the Progressive era where it was also cast as part of eliminating political corruption and workplace inefficiency. This map presents the simple and literal black and white argument. Thirty-six states would need to ratify a Constitutional amendment and as the text explains, Wets lived in a few, highly concentrated areas. The Drys, or White areas, could easily get the votes they needed.

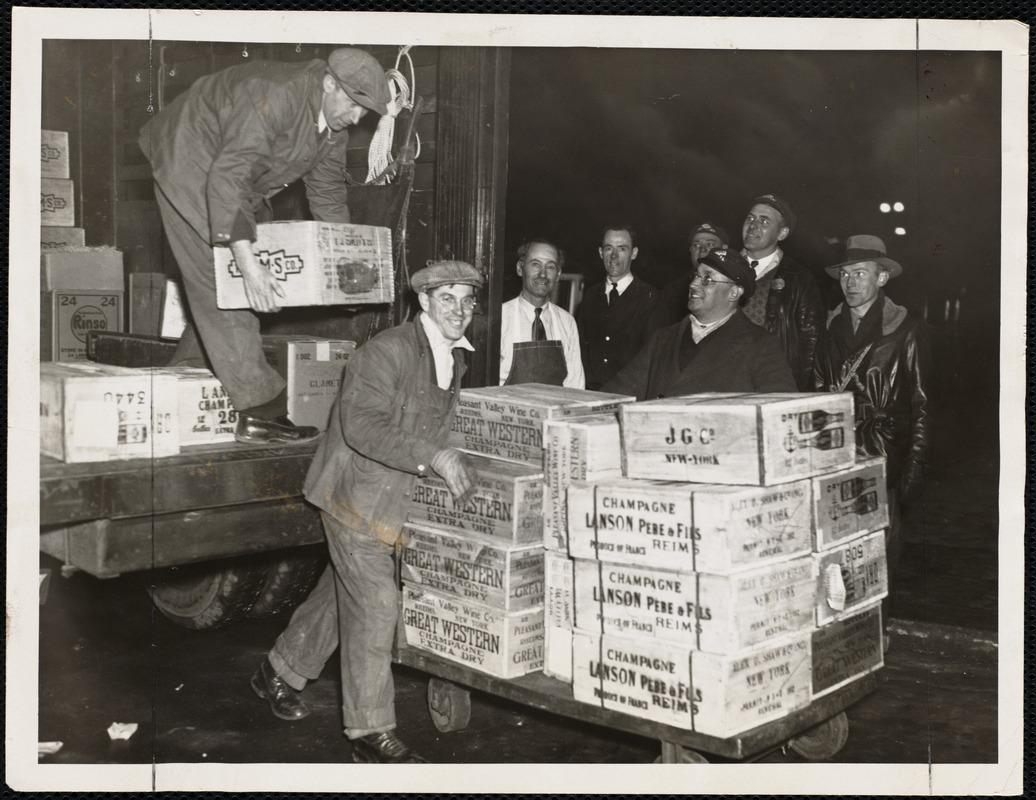

“Booth at Hotel Statler, May 4, 1932” and “First Load at Copley Plaza,” in Boston Herald

December 6, 1933.

Courtesy Print Department.

The prohibition of the sale and consumption of alcohol did little to change behavior and resulted in increased criminality to meet the continued demand. Within five years of its passage, a new national campaign to repeal the 18th Amendment was underway. Again, a state-by-state strategy was pursued as the voters in this 1932 photograph at Boston’s Statler Hotel cast their ballots in favor of the 21st Amendment. This time, however, newly enfranchised women, thanks to the 19th Amendment, would help sway the electorate despite assumptions otherwise. Once passed, alcohol could now be legally unloaded at Boston’s Copley Plaza Hotel as these joyful workers demonstrate.

6. Expanding the Franchise

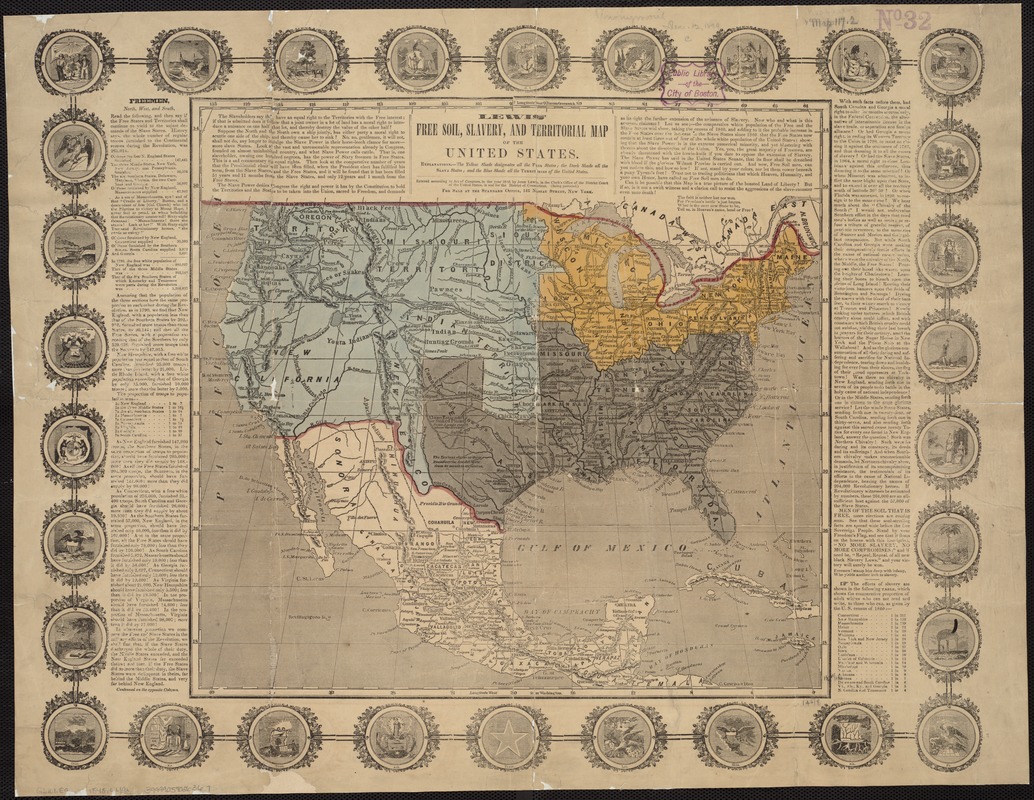

John C. Lewis

Lewis’ Free-Soil, Slavery and Territorial Map of the United States

1848.

The war with Mexico changed the country’s contours. Following the war, a major concern was the status of these newly acquired lands – would they be slave or free? And what rights of citizenship would their residents receive? While state boundaries are not shown on the map itself, the presence of state symbols surround the map and underscore its message: Would the tenuous balance of slave and free states, which had held since the country’s founding, continue or be upset as states were carved out of this new territory?

Metcalf & Clark

The Result of the Fifteenth Amendment, and the Rise and Progress of the African Race in America and its Final Accomplishment, and Celebration on May 19th A.D. 1870

1870.

Courtesy Print Department.

As the various scenes of this 1870 lithograph indicate, the adoption of the 15th Amendment was hailed as a great accomplishment on behalf of the African race. Important figures and events in American history surround the celebration of extending the vote to African Americans. Also noteworthy are the scenes of black children in school, a practice forbidden during slavery. As history would soon prove, it was a hollow victory that merely promised that blacks would not be prevented from voting because of their race—but for the moment, it was time for celebration.

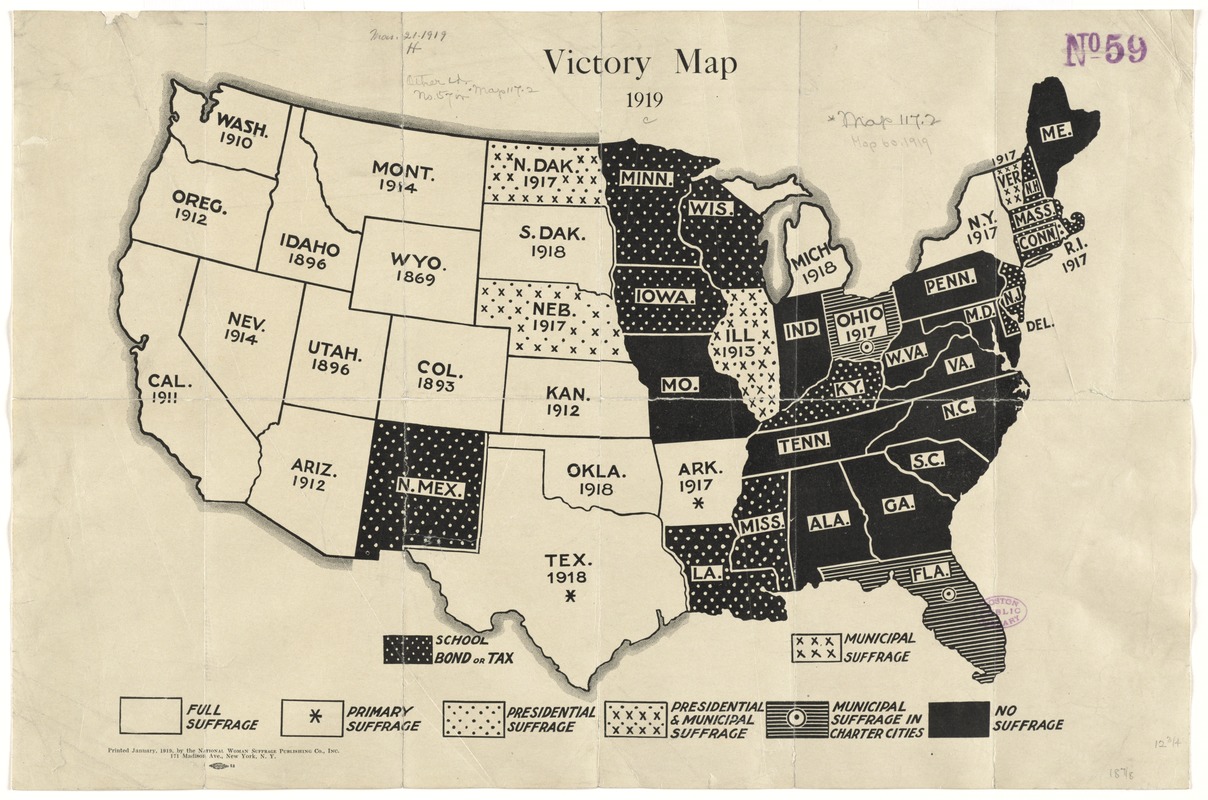

National Woman Suffrage Publishing Co.

Victory Map, 1919

1919.

The campaign to extend the vote to women had been fought for over 70 years and success finally came with the adoption of the 19th amendment in 1920. This battle had been waged state by state and as this map indicates, it was in the western portion of the country where women first gained the right to vote although there was ardent agitation from their sisters in the east. It was in the individual statehouses, controlled by male legislators, that their fate was finally determined. As the map indicates, women accepted partial suffrage before receiving the full vote with the Constitutional Amendment.

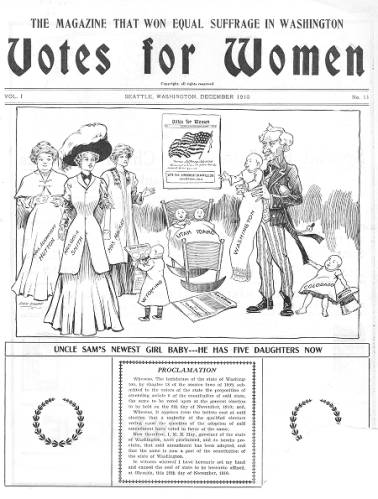

Washington Equal Suffrage Association

“Uncle Sam’s Newest Girl Baby … He Has Five Daughters Now,” in Votes for Women, vol. 1, no. 11

December 1910.

Courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, UW 28335 (page 1).

The right to vote meant different things to different women—an equal voice, a moral influence, the means to protect the less fortunate. After 1900 various groups realized that these different goals could only be accomplished through the powerful and permanent amending of the nation’s Constitution, which required three-fourths of the states to ratify the amendment. As this cartoon shows, women organized on the state level to accomplish this national goal. In December 1910 the newest daughter arrived – the state of Washington.

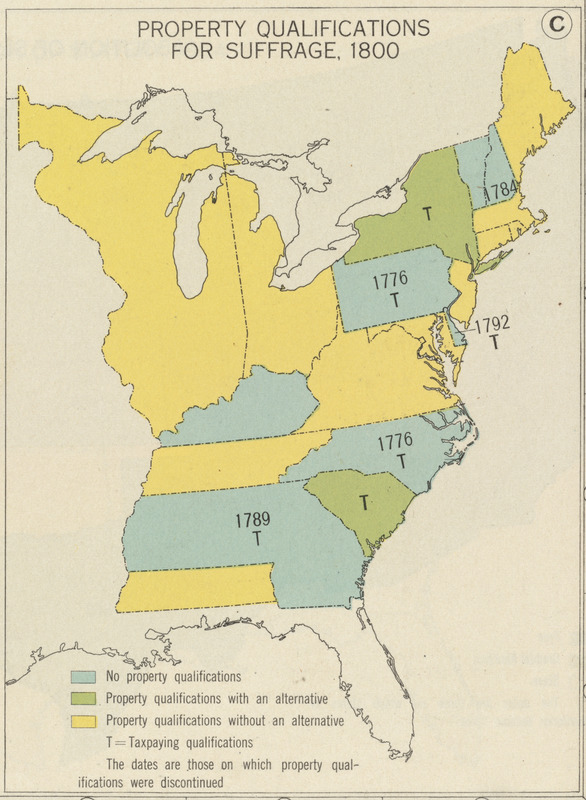

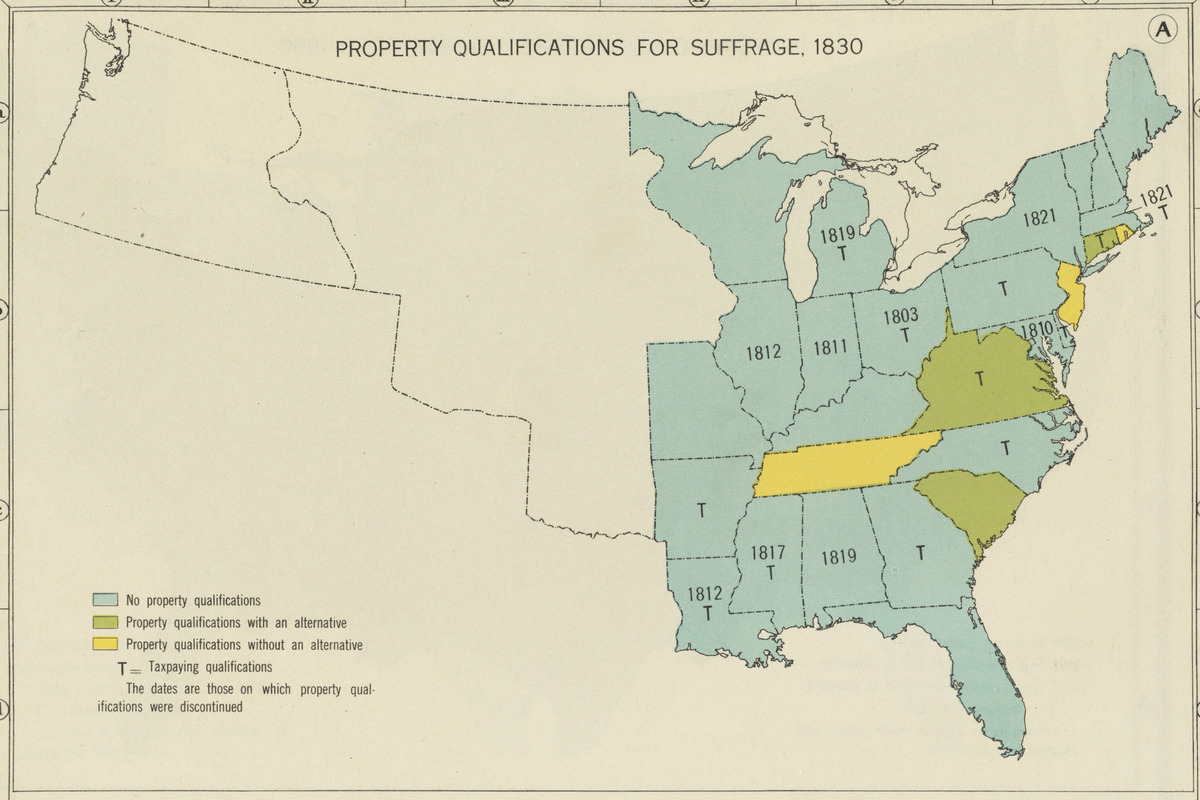

“Property Qualifications for Suffrage, 1800 [and] … 1830” from Charles O. Paullin and John K. Wright, Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States

1932.

When the country was founded, the framers of the Constitution believed that property ownership was a strong indicator of the virtue necessary to participate in the government. Taken together, these two maps tell the story of the evolution of property requirements for voting. In 1789, most of the original 13 states had property or taxed-based criteria. By 1830, between westward expansion, the acquisition of inexpensive land, and the advent of Jacksonian democracy, the notion of property requirements had fallen away. The beginnings of an urban working class, who had little hope of acquiring land, also contributed to the demise of this criterion.

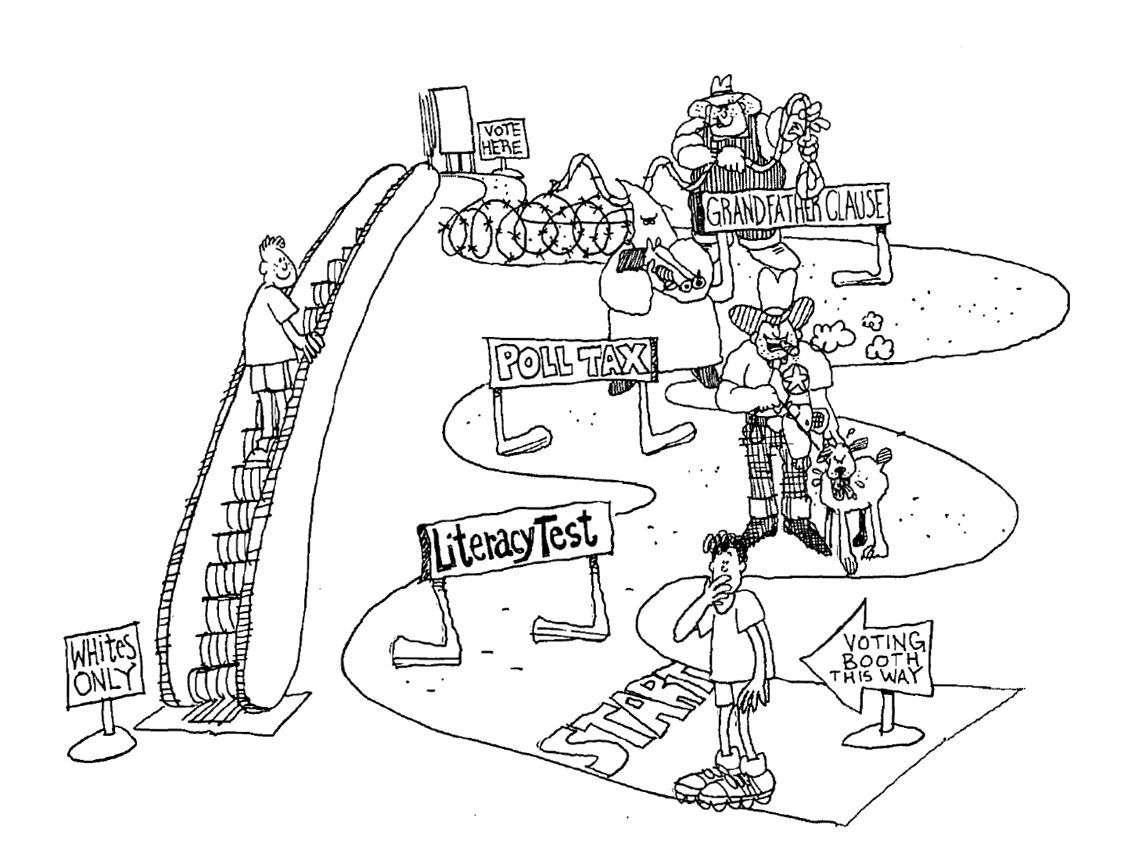

“In what ways did the laws in this illustration deny African Americans the right to vote?” from Kenneth Rodriquez, We the People … The Citizen and the Constitution, Teacher’s Guide

1995.

The right to vote is not guaranteed in the Constitution. The 15th, 19th and 26th Amendments merely state that individuals shall not be prevented from casting ballots based on race, sex or age respectively. As this cartoon illustrates, the 15th Amendment, adopted in 1870, only promised that race would not be an obstacle to voting. Other barriers, such as literacy tests, poll taxes, and grandfather clauses, would be imposed. It would take Federal legislation and 95 years until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 guaranteed blacks the right to vote.

Credits

Curators

Ronald Grim

Debra Block

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center Staff

Debra Block, Director of Education

Lauren Chen, Cataloger

Stephanie Cyr, Senior Cataloger

Ronald Grim, Curator of Maps

Janet Spitz, Executive Director

Evan Thornberry, Reference and

Preservation Librarian

Catherine Wood, Office Manager

Additional Research Assistance

Jane Winton, Print Department, BPL

Lauren Hewes, American Antiquarian Society

Graphic Design and Production

One2tree

The Market King

Framing and Matting

Andrew Leonard

Digital and Web Services

Tom Blake

Allison Blakeslee

Bahadir Kavlakli

Beth Prindle

Lending Institutions and Individuals

American Antiquarian Society

Boston Public Library Print Department

Mark Newman

José-Luis Olivares

University of Virginia Special Collections

University of Washington Libraries Special Collections

Press

“Boston Public Library to Host Open House Exhibit”

The Boston Bulletin

April 19, 2012

Page 6

“Open House at Leventhal Center: Five things to know on Thu, April 19.”

by Cate Lecuyer

Back Bay Patch

April 19, 2012

“Gerrymandering and America Votes”

by Valarie Seabrook

Fenway News Online

July 20, 2012

“Musings on being an American and the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center in Boston”

by Mary Kay

Out and About in Paris (Blog)

June 5, 2012

“Boston City Council Meeting: Five things to know on Wed, Feb. 22. ”

by Cate Lecuyer

Back Bay Patch

February 22, 2012