Introduction

Maps of imaginary places have accompanied literature for centuries. Visualizing the fanciful worlds described in works of fiction sets the stage for events taking place in a story, and often provides insight into the characters themselves. In this exhibition of forty items, visitors will discover maps from a variety of fictional genres, learn how authors create imaginary worlds, and appreciate why descriptive geography is essential to the story. People and creatures, even those who exist only in tales, are related to place, and maps of their imaginary worlds allow readers to be transported into the geography of fantasy.

1. Real World

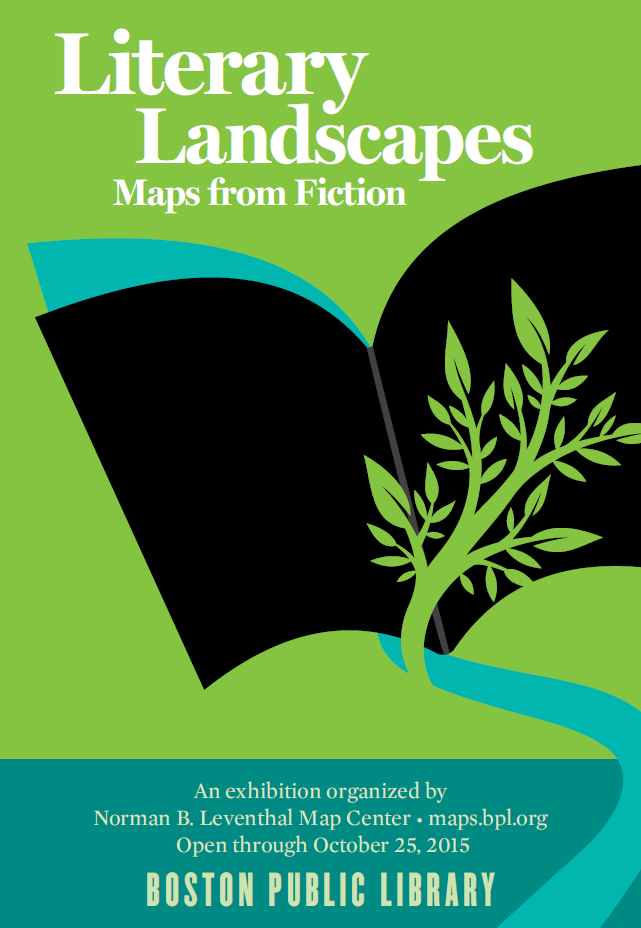

Holling C. Holling

Paddle-To-The-Sea

Boston, ©1969.

Used by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company

Many works of fiction take place in the geography of the real world. The natural and cultural world of the Great Lakes region is described in this tale of geographical fiction by Michigan-born author Holling C. Holling. Paddle-to-the-Sea tells the story of Paddle, a toy canoe carved by a young Indian boy, and its journey from the Lake Helen Reserve in Nipigon, Ontario, to the Atlantic Ocean and beyond. The map displayed here illustrates Paddle’s exciting four-year journey from the cabin on the northern shore of Lake Superior to the coast of France.

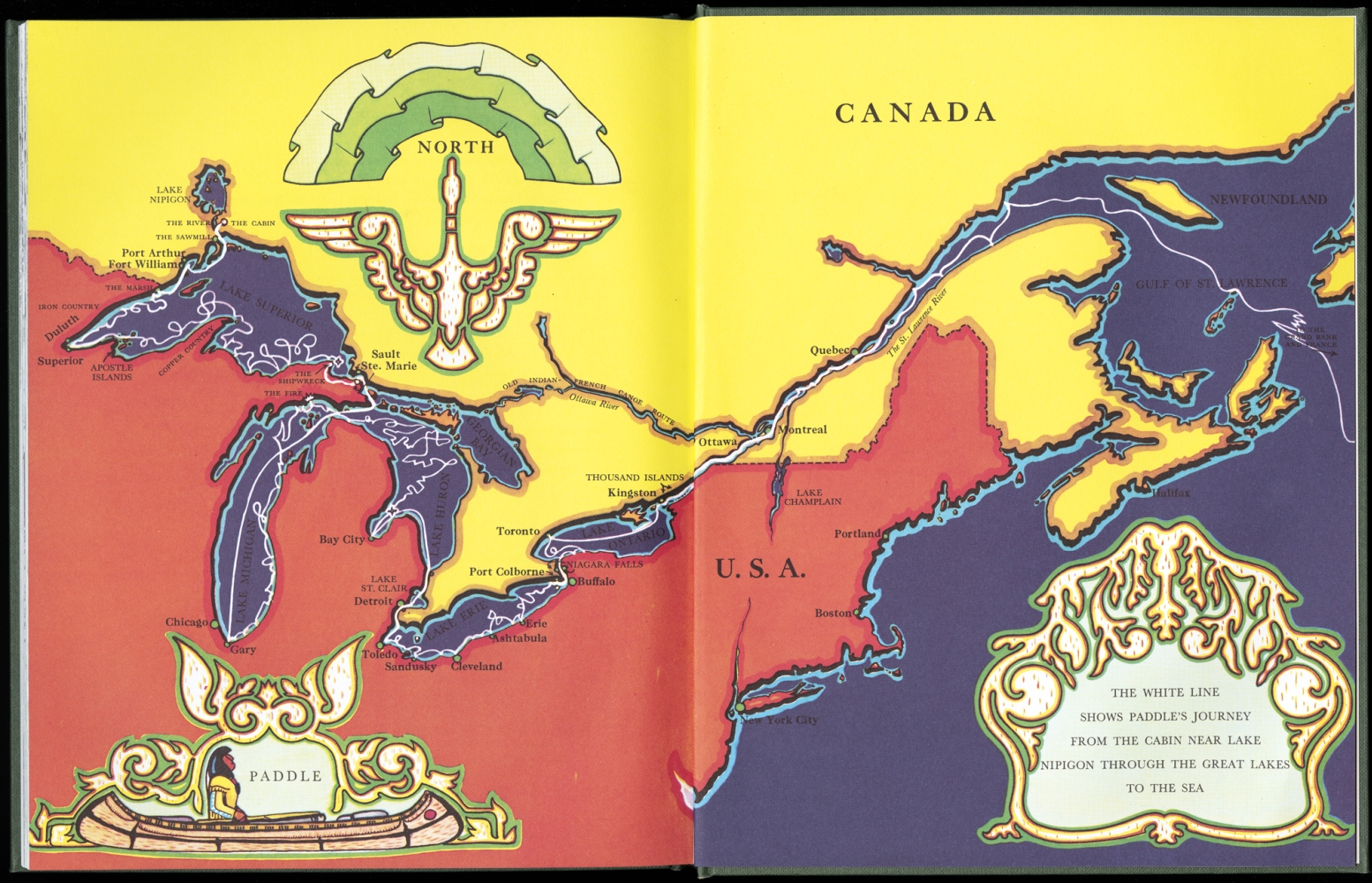

Molly Maguire, Designer; Jim Wolnick, Illustrator

The Sherlock Holmes Mystery Map

Los Angeles, 1987.

Courtesy Molly Maguire and Aaron Silverman

The adventures of Arthur Conan Doyle’s eccentric detective Sherlock Holmes are illustrated on this late-20th century pictorial poster. Two magnifying glasses, containing maps of Victorian-era England and London, are numbered to identify locations associated with the Holmes stories. Illustrations from a number of tales surround the map, and feature characters such as Holmes’ loyal colleague Dr. John Watson, his adversary Professor Moriarty, and a vicious hound from “The Hound of the Baskervilles.”

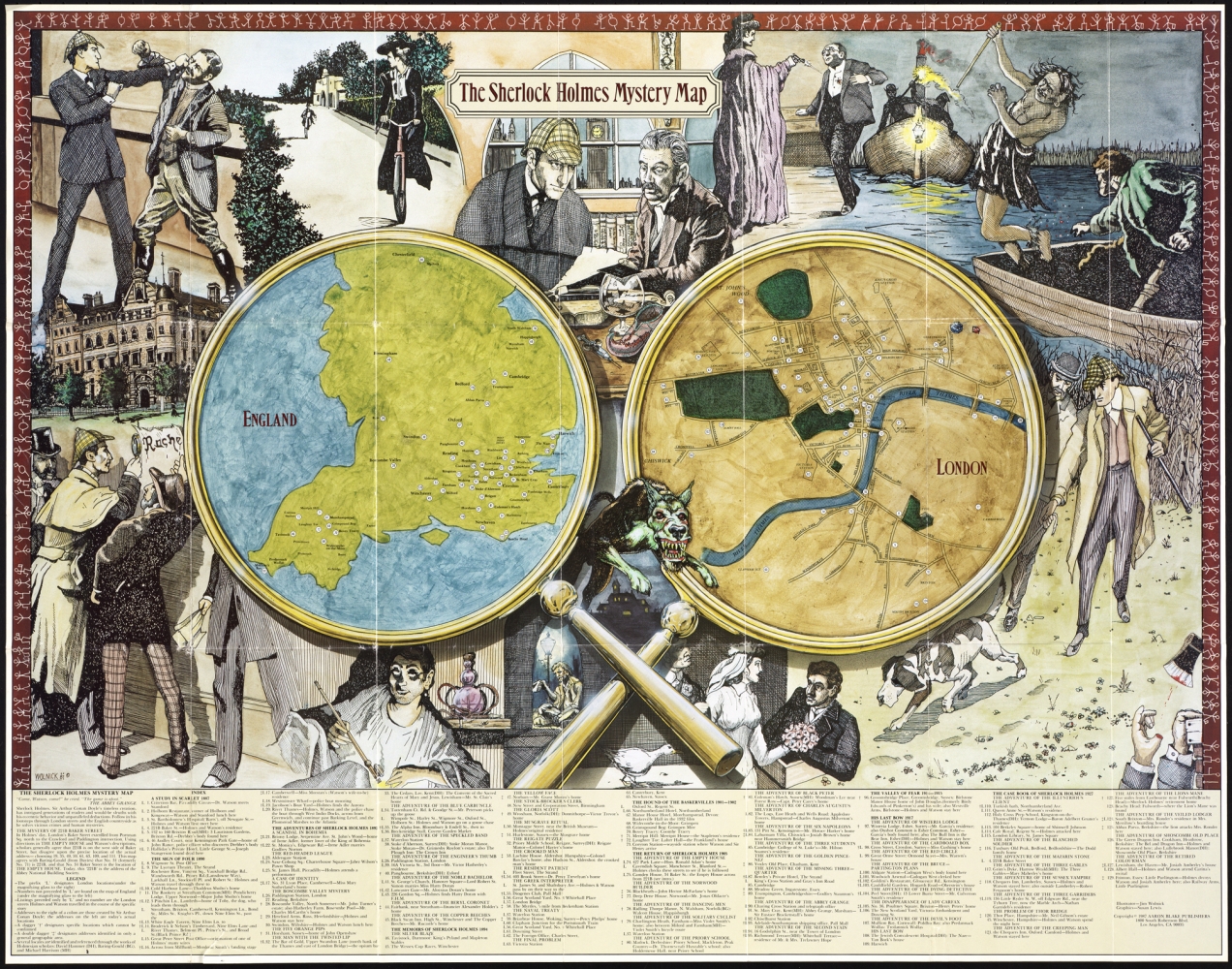

Everett Henry

The Voyage of the Pequod from the Book Moby Dick by Herman Melville

Cleveland, Ohio, 1956. Images copyright © 2000 by Cartography Associates

Courtesy Cartography Associates

Maps appear in many tales of exploration. Herman Melville’s adventurous tale of the crew of the Pequod and their journey in search of the great white whale begins on the island of Nantucket. The suspenseful voyage, depicted by a yellow-orange current on this mid-20th century map, takes the crew from the island to the South Seas. Revenge-driven Captain Ahab leads the crew to a deadly encounter with Moby Dick in the Pacific Ocean, leaving Ishmael as the lone survivor, and the narrator of the story. Main characters appear on this pictorial map, as do vignettes from life on a whaleship.

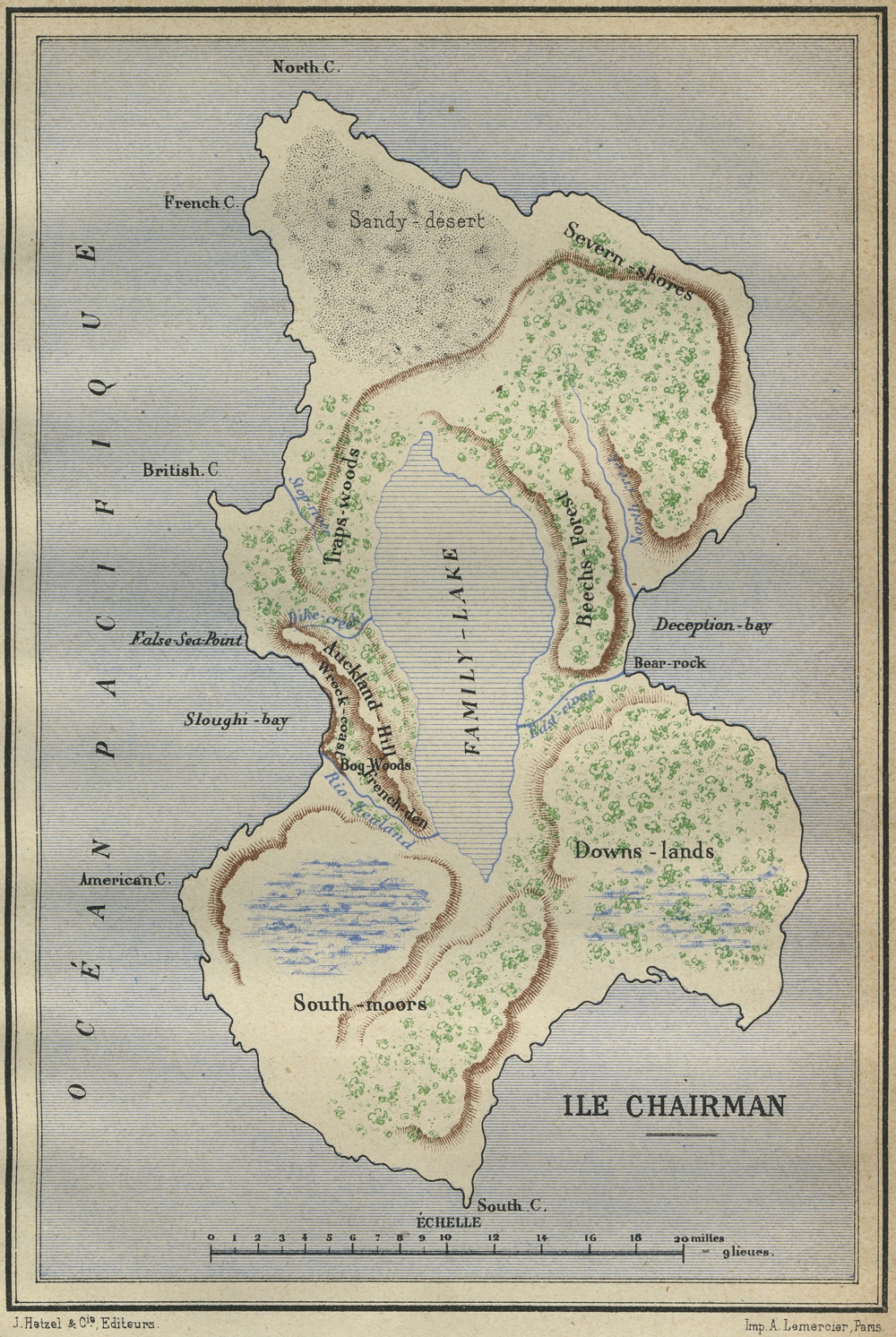

Jules Verne

“Ile Chairman” from Deux Ans de Vacances in Magasin Illustré d’Éducation et de Récréation

Paris, 1888.

Courtesy Trustees of the Boston Public Library

Adventure writer Jules Verne often combined both real and imaginary places and events in his works. For his multi-part story Deux Ans de Vacances (Two Years’ Vacation), the author created an imaginary island as the setting. A group of schoolboys traveling from New Zealand are stranded on the desert island after their ship is caught in a storm. They name the island “Ile Chairman,” and for two years survive many wild adventures until a ship passes by and they escape imprisonment. Verne’s map details the topography of the island, complete with forests, hills and a large lake.

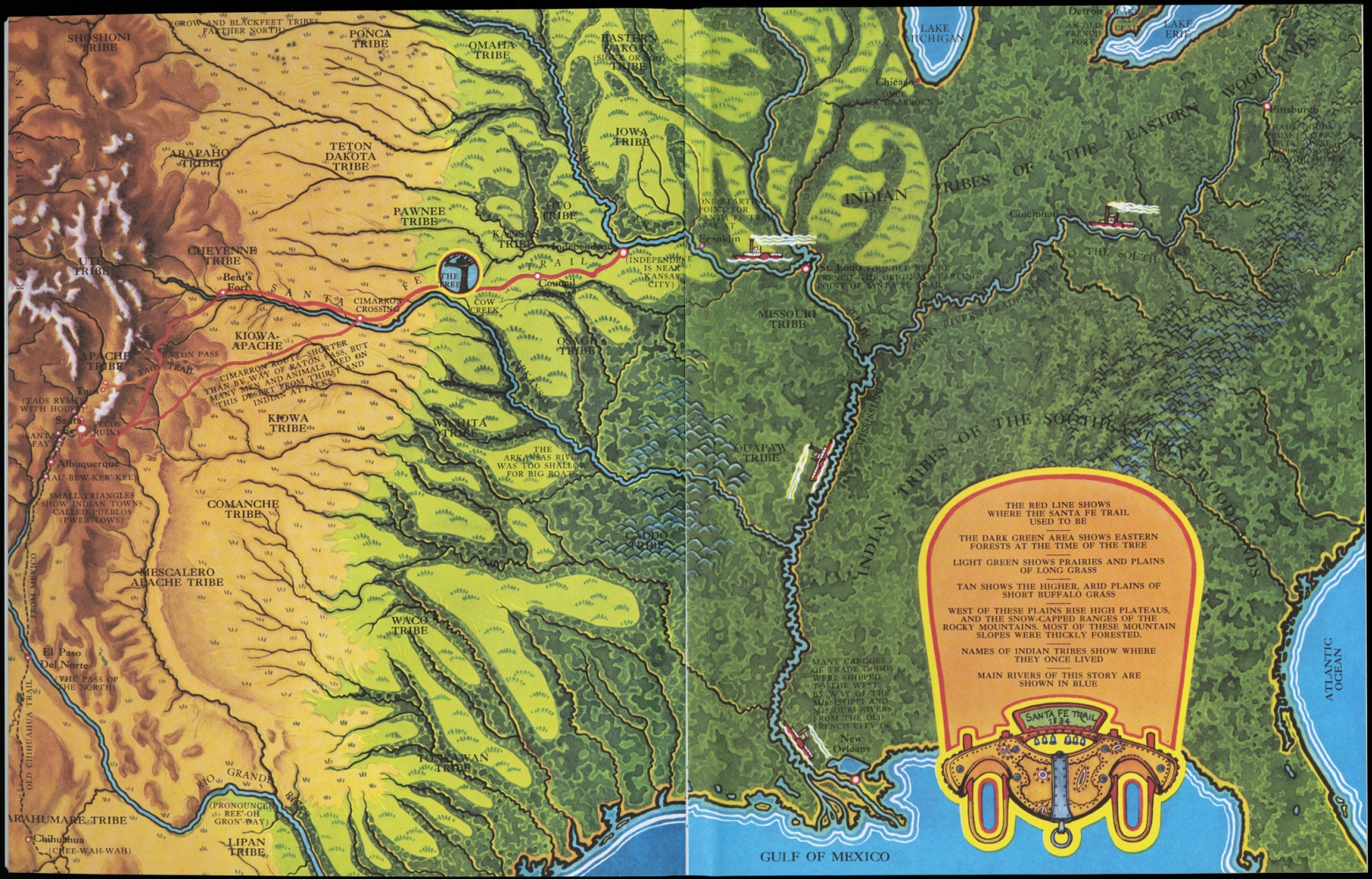

Holling C. Holling

Tree-In-The-Trail

Boston, ©1942.

Used by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company

Holling C. Holling’s tale about the life of a revered cottonwood tree on the Santa Fe Trail discusses geography, history and commerce in the Great Plains and the Southwestern United States. The Trail, starting in western Missouri and ending in Santa Fe, New Mexico, was a trading route for centuries among Native Americans and later by Europeans. The story begins with a young boy of the Kansas tribe who rescues a small cottonwood tree from a buffalo stampede. The tree survives for hundreds of years and is viewed throughout its life as a protector, a meeting place, and a post-office. The location of the trail is outlined on this map.

2. Travel to Other Worlds

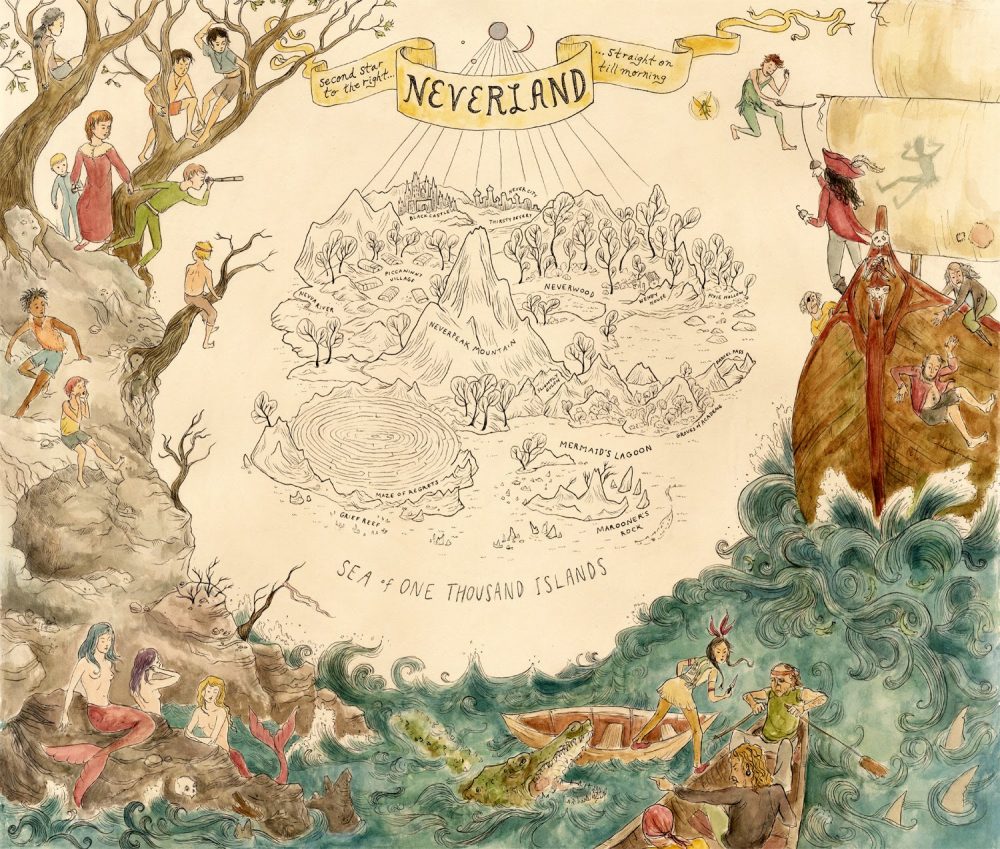

Jacqueline McNally

Neverland

Baltimore, 2011.

Courtesy Jacqueline McNally

Travel to other worlds is a common theme in many fantasy stories where characters journey from the ordinary, “real” world to a realm of magic and wonder. Characters learn valuable, often life-changing, lessons in the enchanted world and return home for the better. In J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan and Wendy, the Darling children fly from their London nursery to Neverland with Peter, a magical boy who would never grow up. The tale ends with Wendy and her brothers realizing that home is where they belong, and they return with the memories of their adventure. Artist Jacqueline McNally illustrates Neverland in the map displayed here. Characters surround the island which features a mermaid lagoon, a maze, mountains, forests and villages.

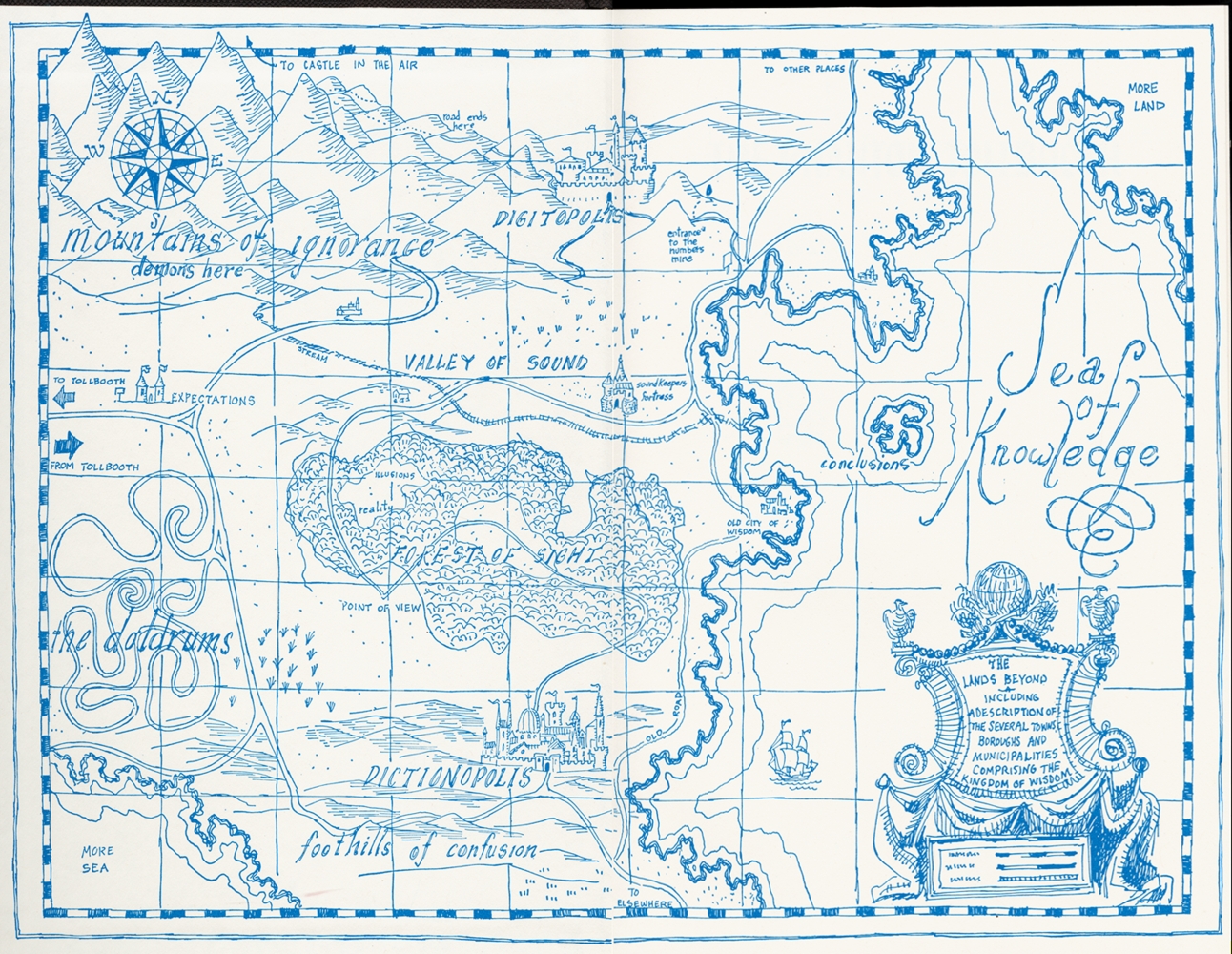

Norton Juster and Jules Feiffer

“The Lands Beyond” from The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster

New York, c1961; reproduction, 2014.

Courtesy Penguin Random House

A boy named Milo takes an educational journey in Norton Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth. Milo is unambitious and always bored, until one day he builds a toy tollbooth, pays his fare, and drives to The Lands Beyond in his electric car. The map displayed here illustrates this world of two rival kingdoms– Dictionopolis, where words are worshipped, and Digitopolis, where numbers rule. Regions of knowledge are surrounded by those of unawareness, such as the “Mountains of Ignorance” and “The Doldrums.” Milo’s adventure was one of learning, and he returns home the better for it.

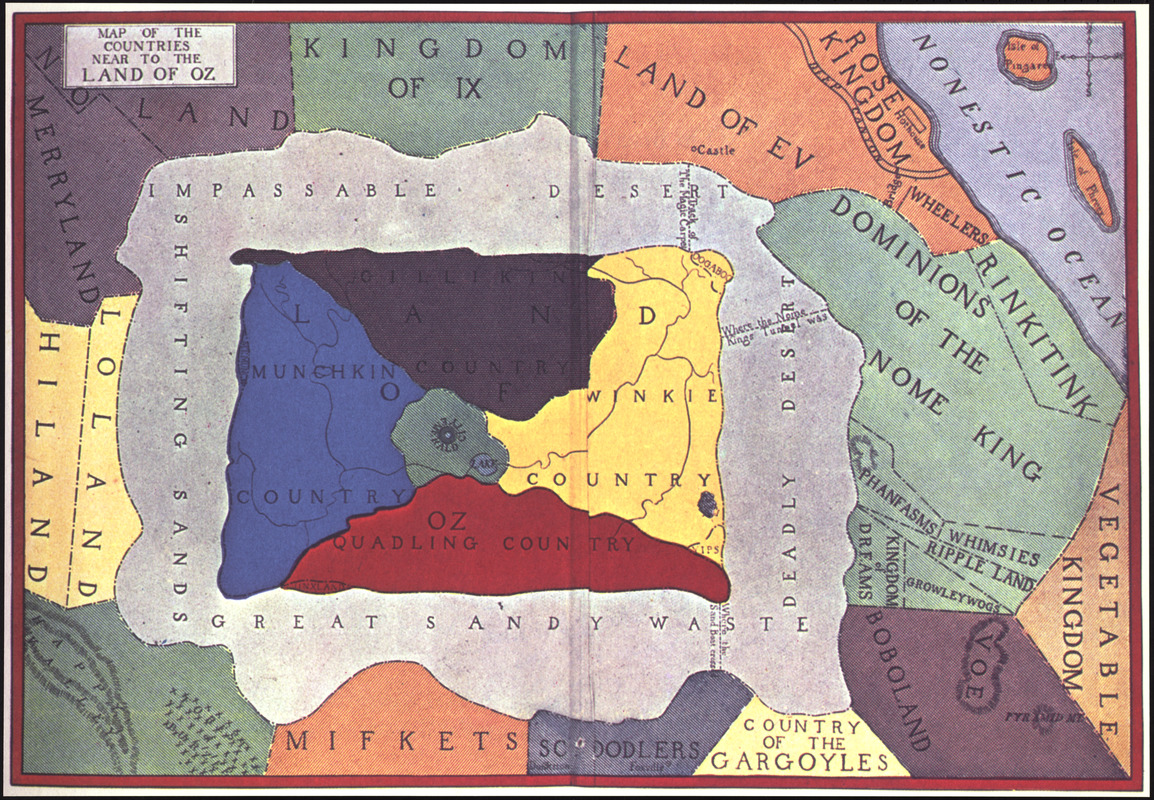

John R. Neill

“Map of the Countries Near to the Land of Oz,” from Tik-Toc of Oz by L. Frank Baum

Chicago, 1914; reproduction, 2014.

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz tells the story of Dorothy, a young girl living on a Kansas farm, who is transported with her dog Toto to the magical and utopian Land of Oz by a cyclone. Dorothy and her companions set out on a quest to see the Wizard in Emerald City, each of them searching for a different part of themselves. By overcoming challenges throughout their journey, the travelers discover their innate potential. The map displayed here illustrates the Land of Oz and surrounding countries, incorporating places described through Baum’s eighth Oz story, where Betsey Bobbin from Oklahoma travels to the whimsical land.

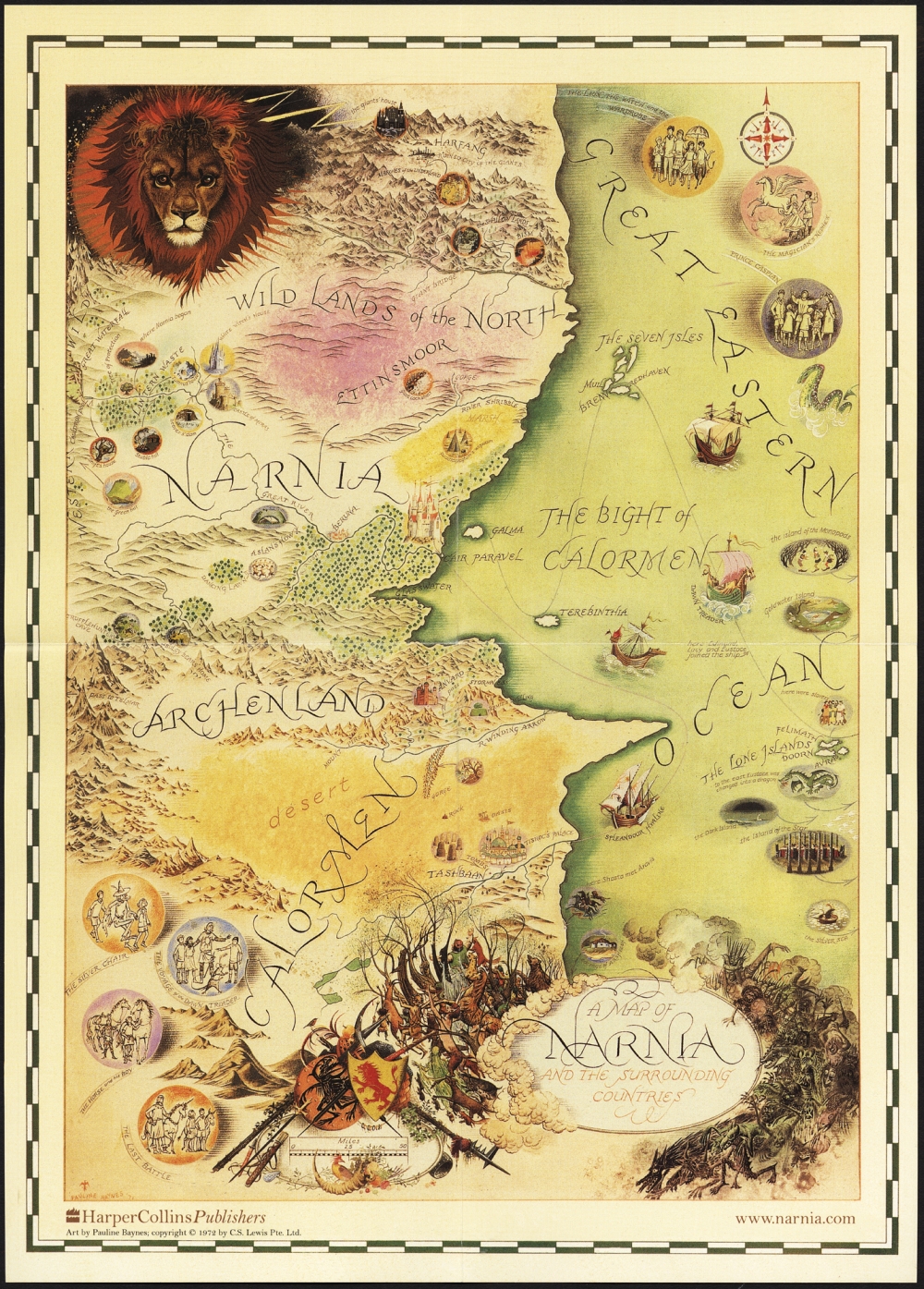

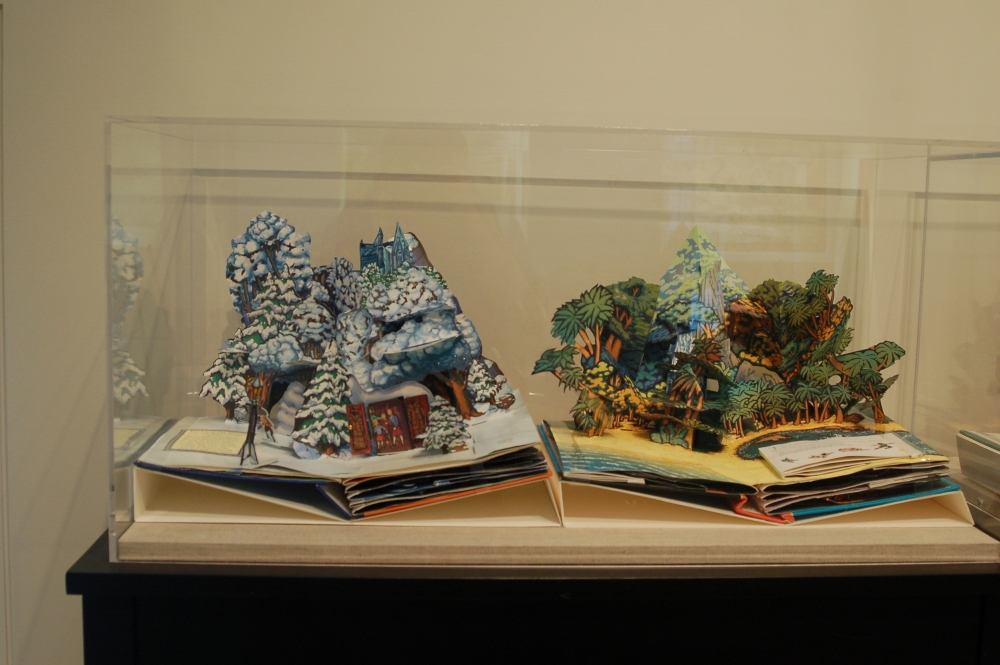

Pauline Baynes.

“A Map of Narnia and the Surrounding Countries,” from The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis.

New York, 2006; reproduction, 2014.

THE MAP OF NARNIA by Pauline Baynes © copyright CS Lewis PTE Ltd 1998

C.S. Lewis commissioned illustrator and trained mapmaker Pauline Baynes to create a map of the lands portrayed in his Chronicles of Narnia series. In The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, the first published book in the series, the Pevensie children discover a large wardrobe in an empty room in the home of Professor Digory Kirke. The children enter the wardrobe, and emerge in the land of Narnia on the other side. The map displayed here illustrates the lands north and south of Narnia, along with a great ocean to the east. In a battle against the forces of evil, the Pevensies prevail and are crowned Kings and Queens of Narnia before returning home to England.

3. Toy and Animal Fantasy

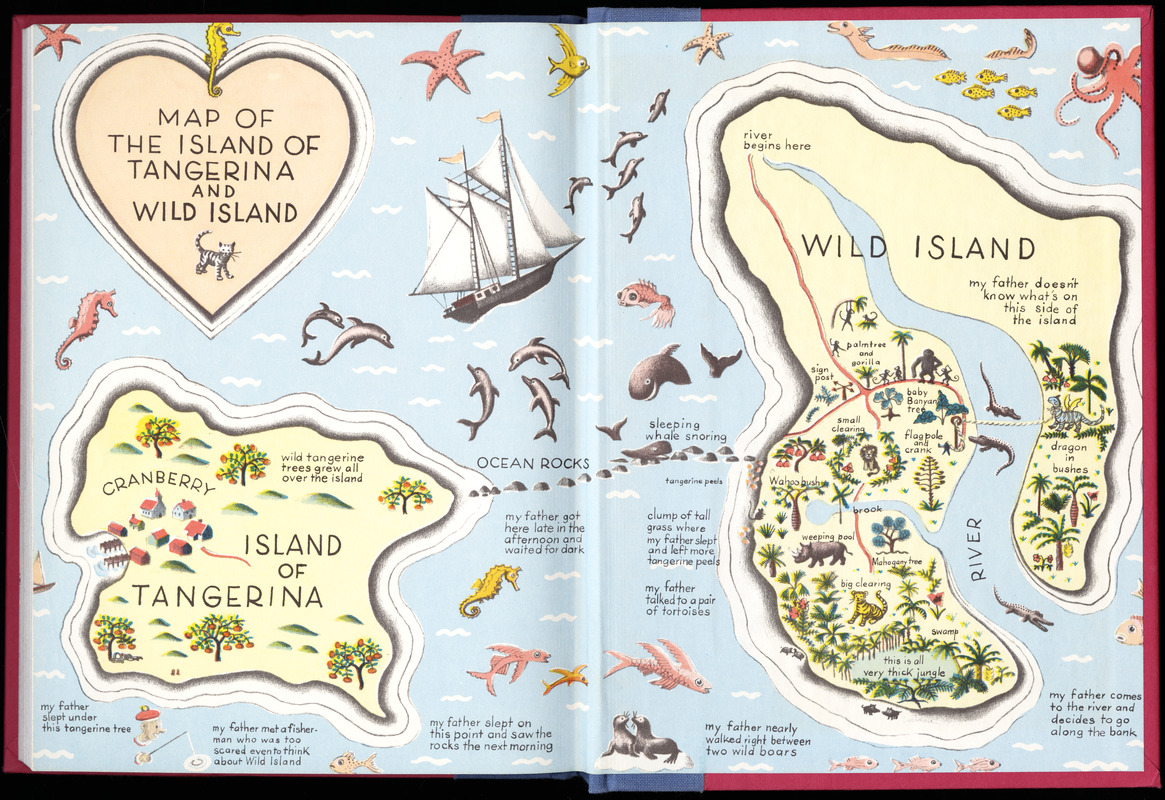

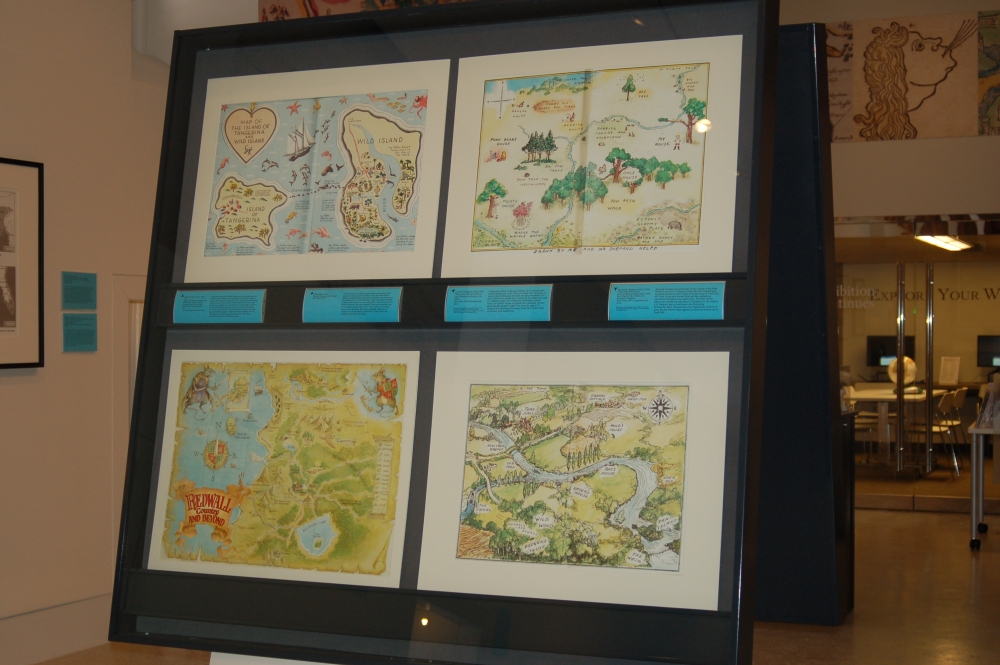

Ruth Chrisman Gannett

“Map of the Island of Tangerina and Wild Island,” from My Father’s Dragon by Ruth Stiles Gannett

New York, c1948; reproduction, 2014.

Courtesy Penguin Random House

Children’s fantasy often includes animals and toys, emulating stories children invent with their own playthings. In My Father’s Dragon, a stray cat tells young Elmer Elevator about a baby dragon who is being forced to carry the lazy animals of Wild Island across a river. Elmer packs various supplies and runs away to rescue the dragon. He sails to the Island of Tangerina and crosses the ocean rocks to Wild Island. Once there, Elmer searches for the dragon, distracting the unfriendly animals with chewing gum, toothpaste and other supplies. The map, showing Elmer’s path on his quest, was drawn by the author’s stepmother, an illustrator of children’s books.

4. High Fantasy

Daniel Reeve

Middle Earth

New Zealand, 2012.

Courtesy Weta Workshop

In works of high fantasy, the reader encounters an alternate world from the first page. J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth is one such location, and this complex realm is described throughout the author’s The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and Silmarillion tales. Home to men, elves, and creatures of all sorts, Middle-earth is where good battles evil throughout the ages. Displayed here is a modern map of the land by artist Daniel Reeve. The varied topography includes mountains, hills, forests, grassy plains, rivers and more, all of which are bounded by a great sea to the west and the land of Rhûn to the east.

Mike Schley

Menzoberranzan

Renton, Washington, 2012. ©Wizards of the Coast, Inc.

Courtesy Mike Schley

R.A. Salvatore’s epic tale of dark elf Drizzt Do’Urden has been engaging readers of Dungeons and Dragons stories since the late 1980s. Drizzt and his kin, known as the drow, hail from the underground city of Menzoberranzan – the City of Spiders. Artist Mike Schley’s map of this complex and treacherous realm is displayed here. The city, along with the lake Donigarten; Narbondel, a column of rock that extends from floor to ceiling; and three crevasses known as rifts, are all found inside the great cavern of Araurilcaurak. Darkness envelops the drow and all they do, contributing to their culture of evil and cruelty.

5. Folklore and Mythology

Bernard Sleigh

An Anciente Mappe of Fairyland Newly Discovered and Set Forth

London, 1917.

This map of Fairyland depicts places from nursery rhymes, fairy tales, Arthurian legends and the folktales of many cultures. Sleigh, a fairy and mythology enthusiast, initially sketched a map of fairyland to entertain his children, adding characters and places from their favorite stories. This map was published in 1917 and intended to decorate nurseries. After Sleigh retired in 1937, the print was turned into a decorative fabric for Rosebank Fabrics. The print was so popular that Rosebank commissioned Sleigh to design other fairy tale patterns for fabrics.

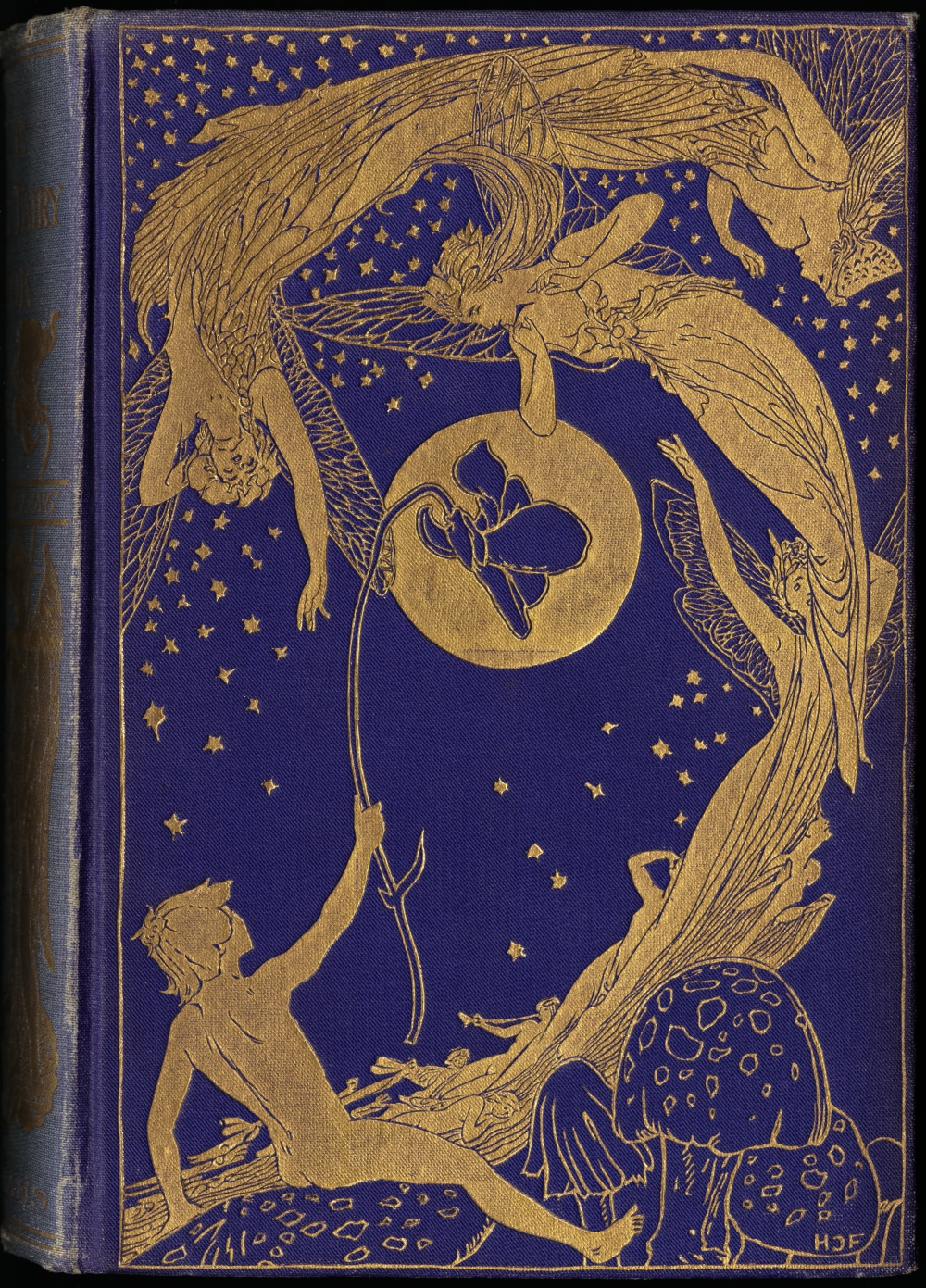

Andrew Lang. Violet Fairy Book (London, 1901)

Crimson Fairy Book (London, 1903)

Orange Fairy Book (London, 1906)

Brown Fairy Book (London, 1910).

Courtesy Trustees of the Boston Public Library

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, children mainly read realistic stories. Fairy tales were considered harmful to children because they contained non-existent creatures and violence. In 1889, Andrew Lang released a collection of fairy tales called The Blue Fairy Book. Its popularity led to 12 colored fairy books over 25 years, with stories from around the world. Four of these are displayed here. Lang supervised the anthologies and credited his wife, nieces and other women with translating and writing the stories. H.J. Ford, who illustrated the covers and stories, also illustrated some of Lang’s other collections, such as his collection of Greek mythology.

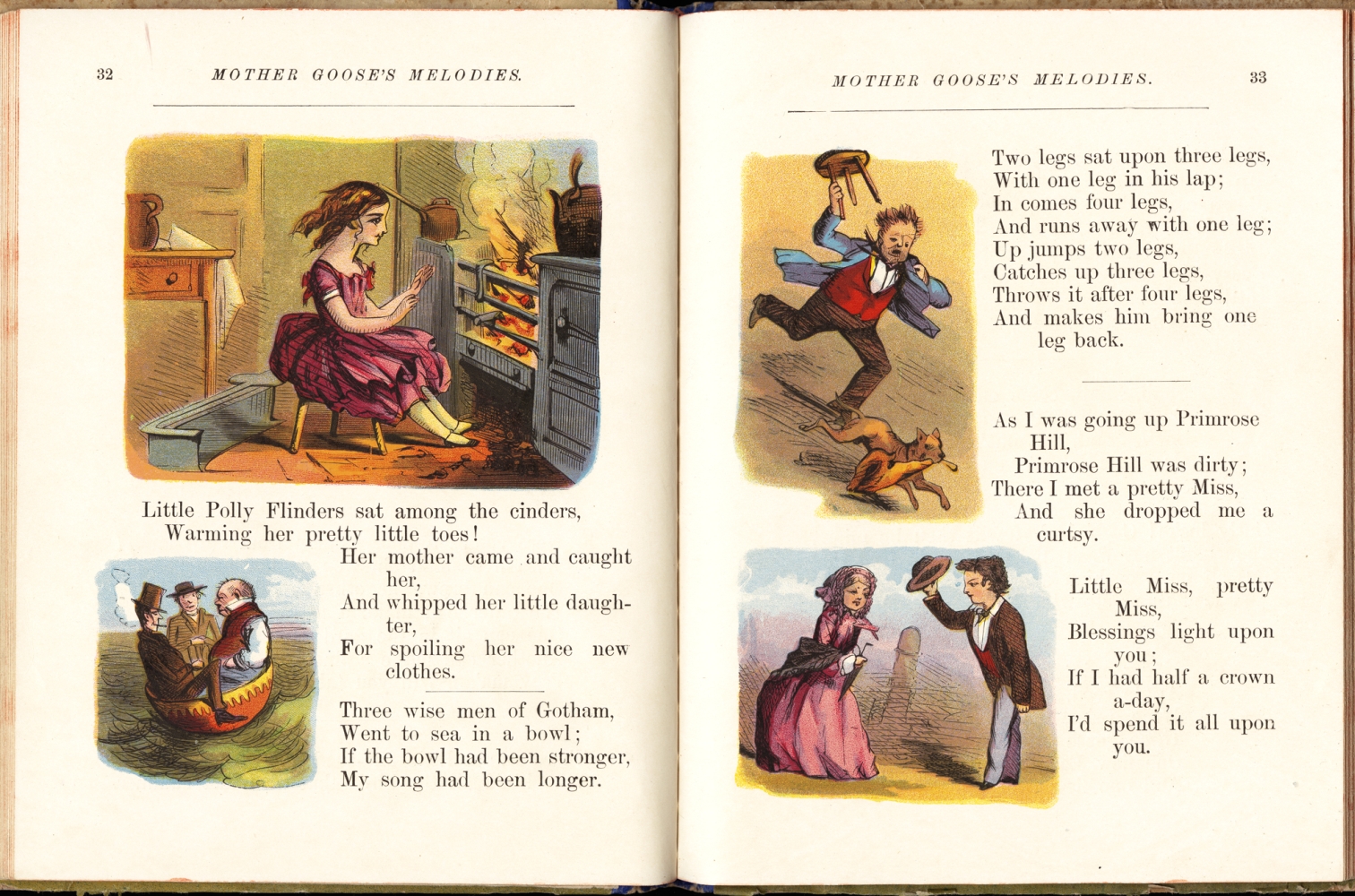

“Three Wisemen of Gotham” from Mother Goose’s Chimes

New York, [1880].

Courtesy Trustees of the Boston Public Library

“Perseus in the Garden of the Hesperides” from Tales of Troy and Greece

New York, 1907.

Courtesy Trustees of the Boston Public Library

Mother Goose became known as the imaginary author of nursery stories after the English publication of Mother Goose’s Melody in the late 18th century. One of these tales, “The Three Wisemen of Gotham,” is depicted in the lower left of the Fairyland map.

This book of Greek myths was edited by Andrew Lang and illustrated by H. J. Ford. The Greek hero Perseus and the Hesperides guarding the tree of golden apples are depicted in the lower right of the Fairyland map.

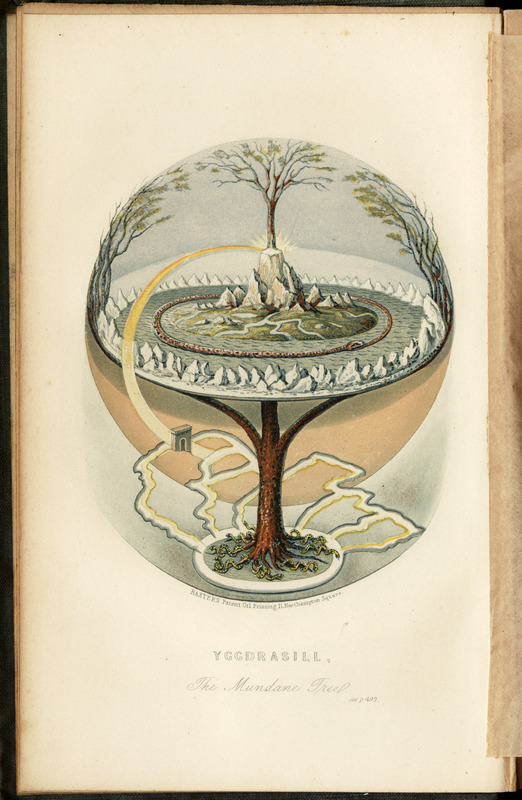

In Norse mythology, the tree Yggdrasill connects the nine worlds. This illustration represents the earliest modern interpretation of Norse cosmology, copied after Magnússon’s depiction of the worlds in layers. Asgard, the world at the top of Yggdrasill, is in the background of the Fairyland map.

Edwin Austin Abbey

The Quest and Achievement of the Holy Grail

1893.

Courtesy Sheryl Lanzel

Noted American artist Edwin Austin Abbey painted a series of murals for the opening of the Boston Public Library’s McKim building in the 1890s. These murals are an amalgam of multiple versions of the Quest for the Holy Grail, particularly stories about Galahad and Parsifal. In the Fairyland map, Arthurian characters are on the mountain and Galahad is in the lower right corner. Reproductions of the murals show Galahad, a knight of King Arthur’s Round Table, embarking on a quest for the Holy Grail (top). At the castle of King Amfortas, he fails to ask about the procession of the Grail and does not break the spell sickening the king (middle). He eventually becomes the King of Sarras and builds a golden tree. When the tree is completed, Galahad sees the Grail and ascends to heaven (bottom).

6. Styles of Maps

Keith Thompson

“The Great War 1914,” interior illustration from Leviathan by Scott Westerfeld, illustrated by Keith Thompson, from Simon Pulse, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing Division

New York, 2009; reproduction 2014.

Courtesy Keith Thompson

The steampunk/biopunk Leviathan Trilogy reimagines World War I in a technologically advanced alternate world. Darwinists, corresponding to the Allies, use biotechnology to fabricate creatures like the whale-based airship Leviathan. The Central Powers equivalent, Clankers, use steam-powered machines to wage war. The series follows Deryn, a girl disguised as a boy to serve in the British Air Service, and Aleksander, son of assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, on their travels aboard the Leviathan. This map illustrates countries’ attitudes in the style of caricature maps. In Thompson’s map, attention centers on Austria-Hungary attacking Serbia in retaliation for the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, in Sarajevo.

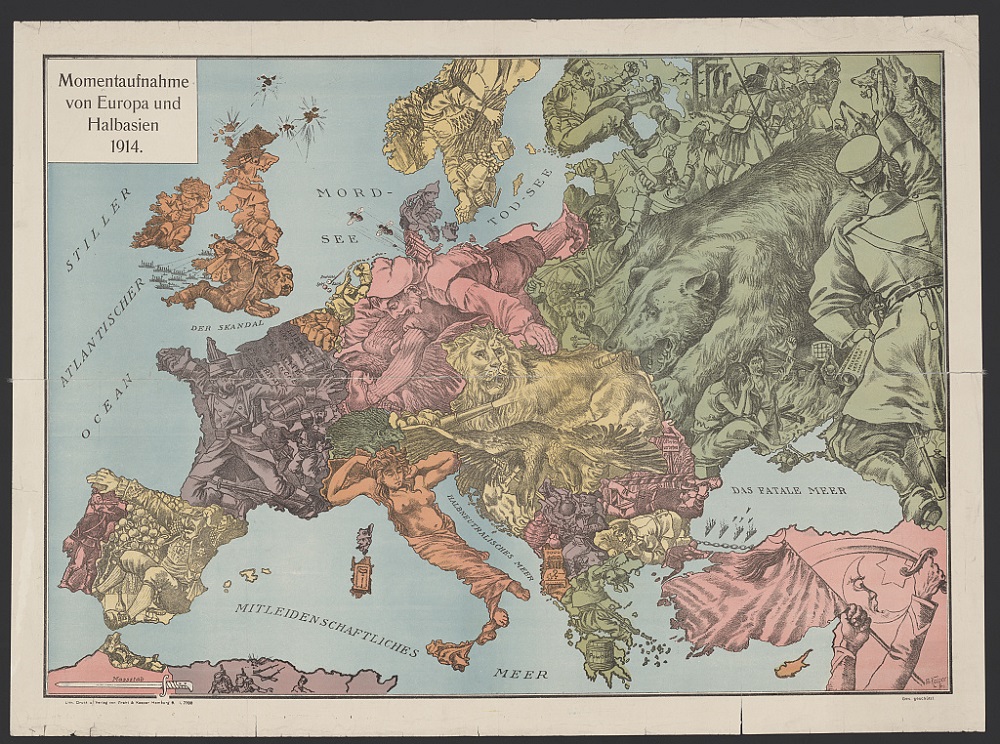

W. Kaspar

Momentaufnahme von Europa und Halbasien 1914

Hamburg, [1915?]; reproduction, 2014.

Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Caricature maps use stereotypes and symbols for political or humorous commentary. Illustrating characteristics of and attitudes towards countries, they were often used as propaganda to stimulate nationalism and mock enemies. This map of Europe during World War I shows countries as national symbols like the British bulldog and the Austro-Hungarian double-headed eagle. Germany, where the map was produced, is represented by Deutscher Michel, a national personification like the United States’ Uncle Sam. Enemy Great Britain is harassed by the Indian snake demanding national rights while Russia suffers civil unrest. Seas are cynically renamed, such as the Mord-see (Murder Sea) instead of Nord-see (North Sea).

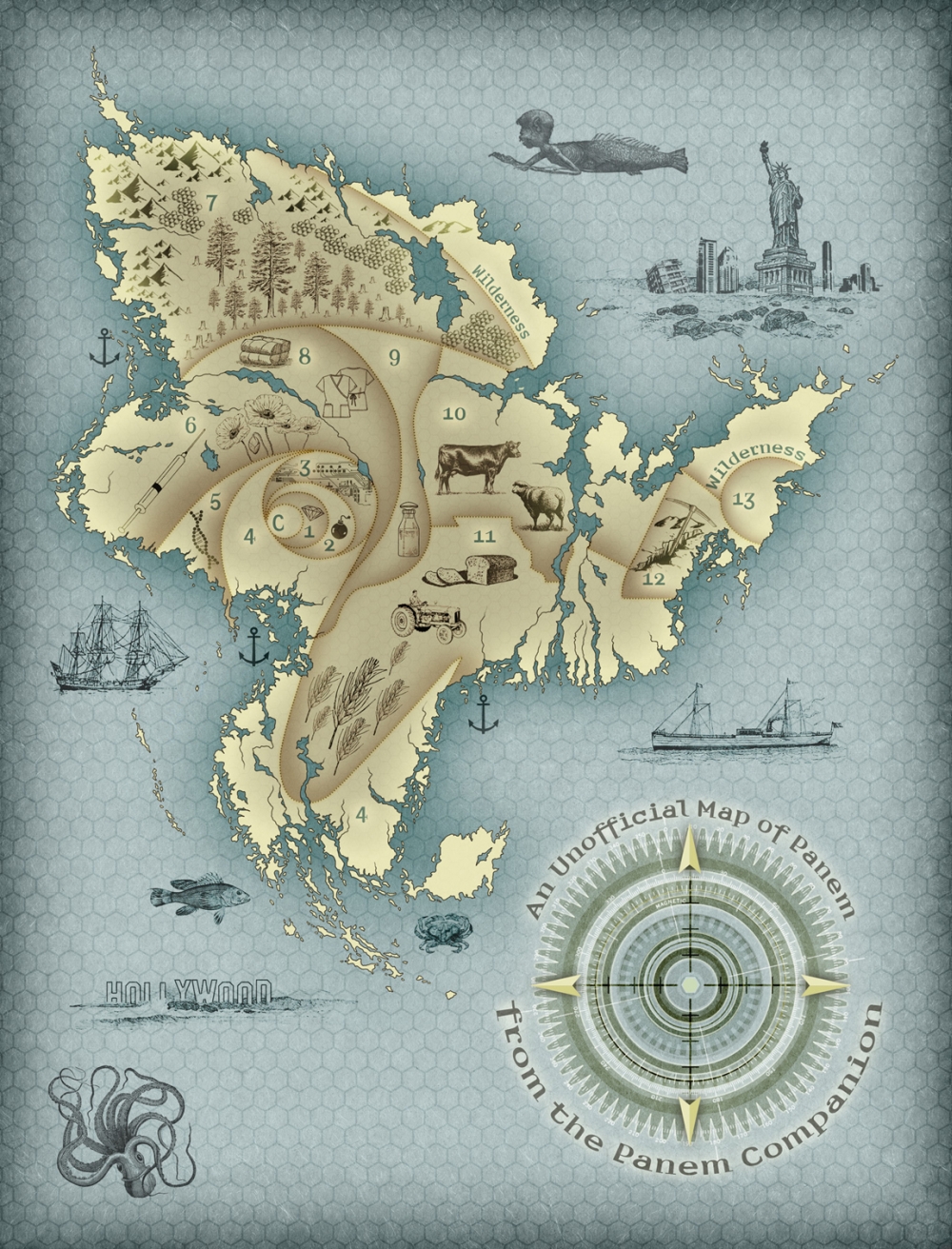

V. Arrow.

An Unofficial Map of Panem from the Panem Companion.

The Panem Companion by V. Arrow, ©2012 Smart Pop Books; reproduction, 2014.

Courtesy V. Arrow

V. Arrow, a fan, created this unofficial map of Panem based on projected geographic changes and information as described in Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games trilogy. In the books, North America collapses after natural disasters and wars for resources. The resulting nation, Panem, consisted of 13 districts controlled by the wealthy Capitol. After a rebellion led by District 13, the Capitol destroyed the district and instituted the annual Hunger Games as reparations. Character Katniss Everdeen is one of the tributes forced to compete in the deadly games. The golden spiral arrangement would facilitate the Capitol’s control and allow allocation of enough land for each district’s products.

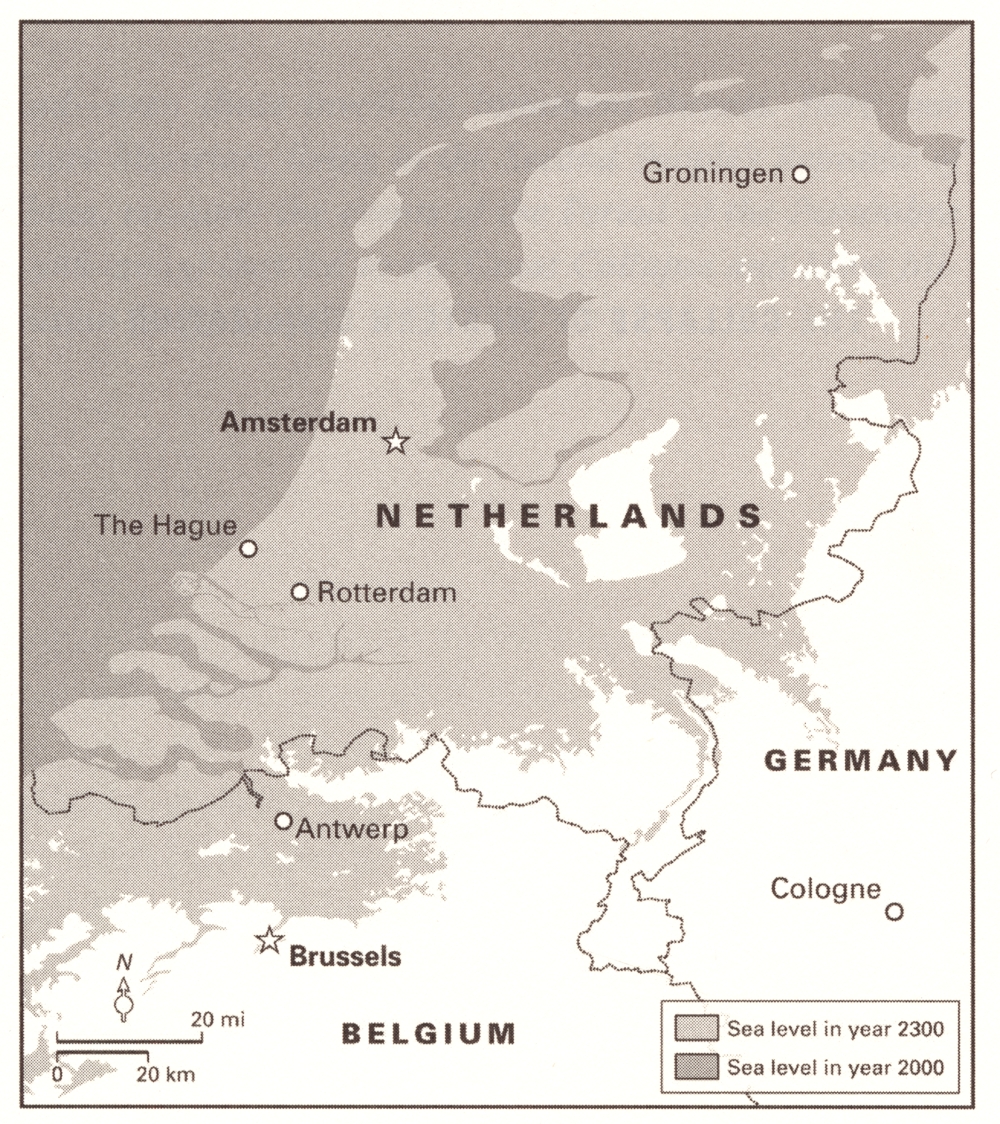

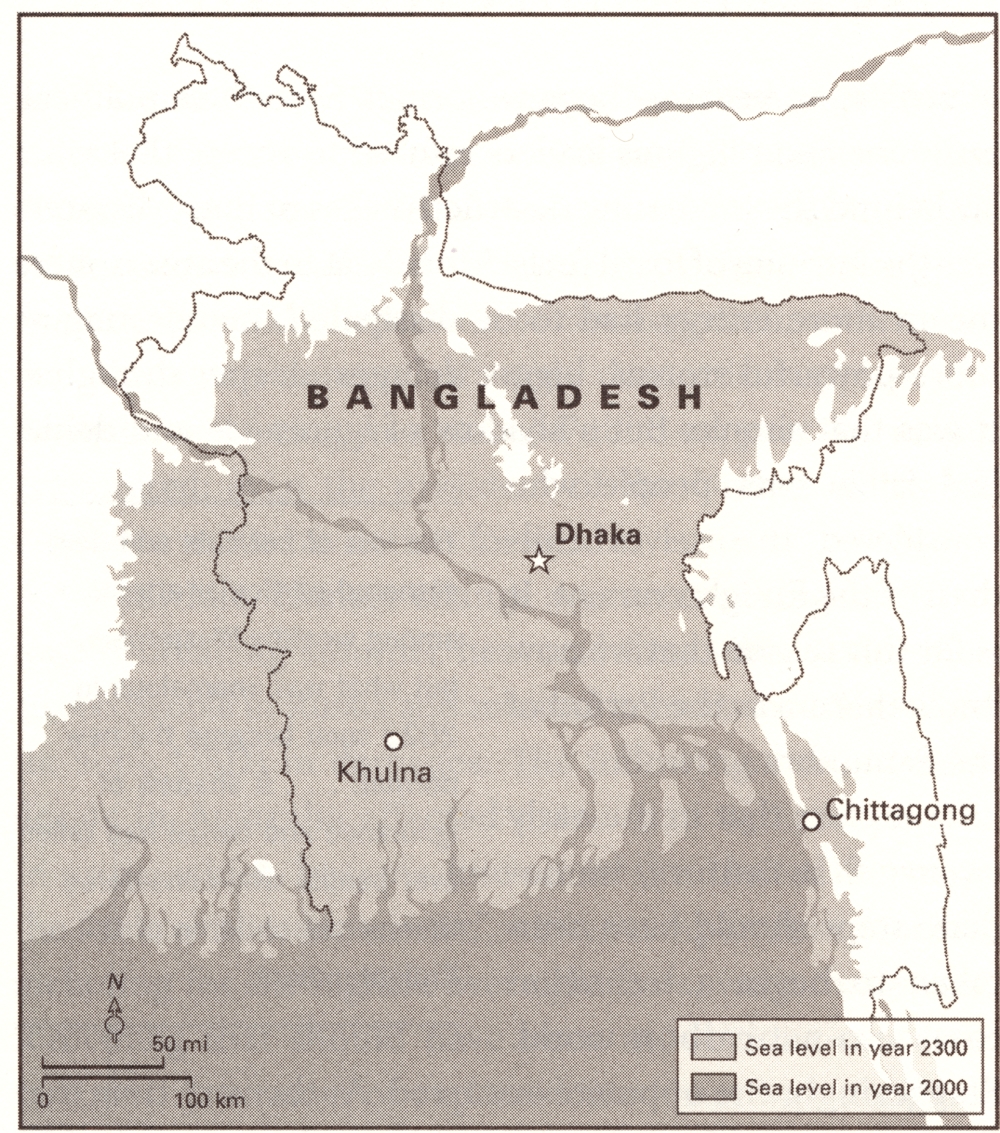

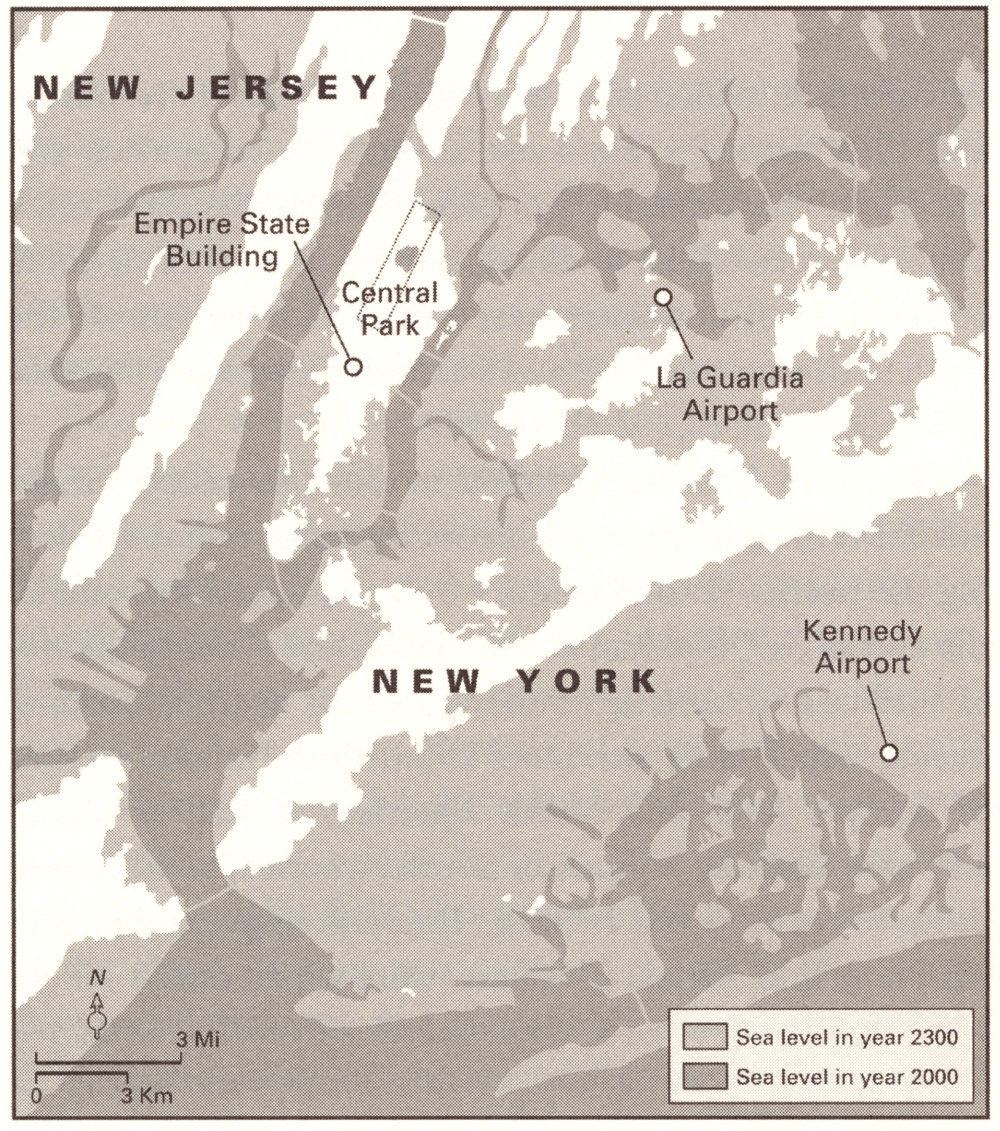

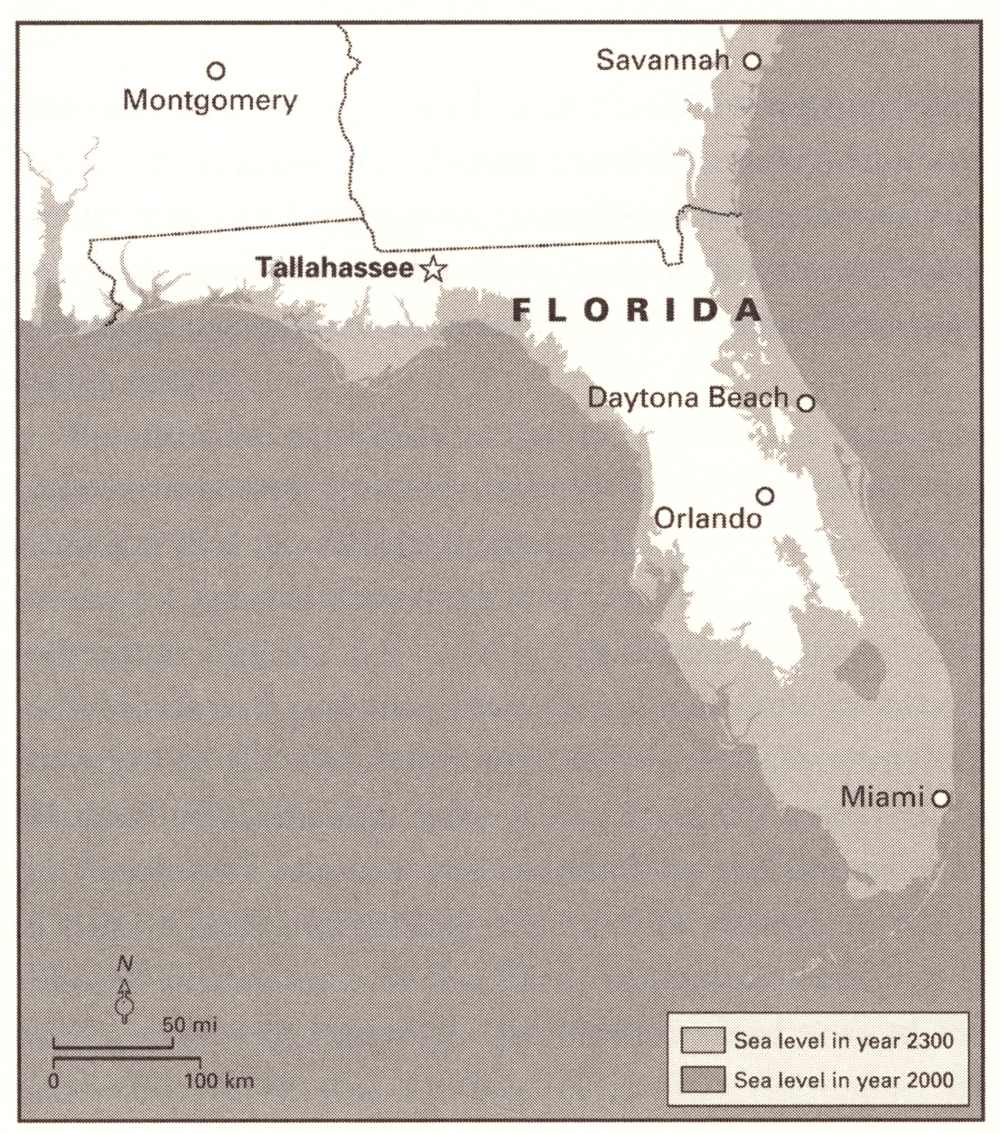

Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway

“Amsterdam,” “Bangladesh,” “New York City” and “Florida” from The Collapse of Western Civilization: A View from the Future

New York, ©2014

Courtesy Columbia University Press

In The Collapse of Western Civilization, a Chinese historian in 2393 documents how policies in the early 21st century led to the collapse of western civilization in 2093. Increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases trapped more heat in the atmosphere, and that energy manifested in extreme weather patterns and temperatures. While scientists of the 21st century knew about climate change, legislation restricting research and failed attempts at regulating emissions prevented action. Western civilizations were least prepared or able to deal with the effects of climate change such as rising sea levels submerging major cities, as seen in the maps above. A similar scenario forms Panem in the Hunger Games series.

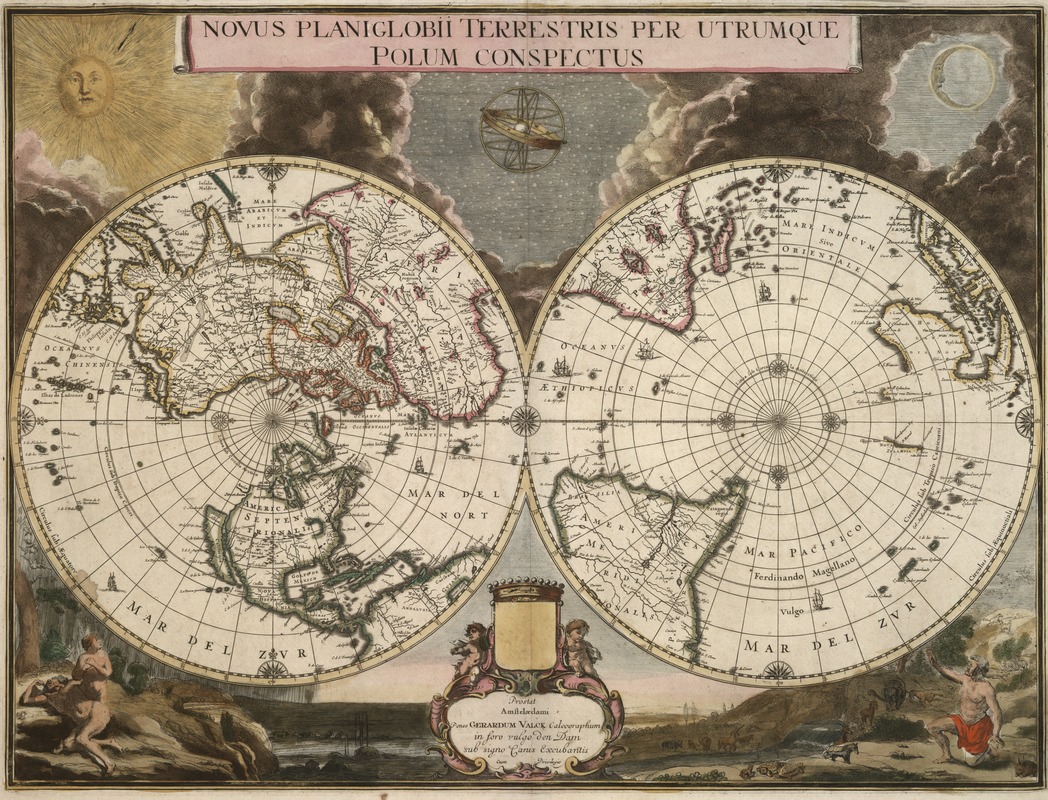

Gerard Valck

Novus Planiglobii Terrestris Per Utrumque Polum Conspectus

Amsterdam, 1695.

Double-hemisphere maps have been a popular way of presenting the earth two-dimensionally since the mid-16th century. Jason Thompson employed this style for his map of H.P. Lovecraft’s Dreamlands. This late 17th-century Dutch example orients the world on the north and south poles, depicting the northern and southern hemispheres. The two hemispheres are set against an artistic backdrop highlighting the Bible’s Genesis story of creation. The sun, moon, and stars emerge from clouds of darkness at the top, while Adam and Eve’s shame after leaving the Garden of Eden is illustrated in the lower left, with Noah selecting pairs of animals for the ark in the lower right.

Bibliography

“About Brian.” Redwall Abbey: The Official Brian Jaques Site. Redwall Abbey. Web. 9 Dec. 2014. <http://www.redwallabbey.com/pages/about.htm>.

Anderson, Douglas A. “Fairy Elements in British Literary Writings in the Decade Following the Cottingley Fairy Photographs Episode.” Mythlore 32.1 (Fall/Winter 2013): 7-20.

Anlezark, Daniel. Myths, Legends, and Heroes: Essays on Old Norse and Old English Literature in Honour of John McKinnell. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011.

Arrow, V. The Panem Companion: An Unofficial Guide to Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games, from Mellark Bakery to Mockingjays. Dallas: Smart Pop, 2012.

Barrie, J.M. Peter Pan. New York: Sterling, 2008.

Barrie, J.M. The Annotated Peter Pan. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2011.

Baxter, Sylvester. The Legend of the Holy Grail as Set Forth in the Frieze Painted by Edwin A. Abbey for the Boston Public Library. Boston: Curtis & Cameron, 1904.

Blackwell, I. A. Northern Antiquities. London: Henry G. Bohn, 1859.

Bloom, Harold. “Introduction.” Modern Critical Interpretations: Dante’s Divine Comedy. New York: Chelsea House, 1987.

Cashdan, Sheldon. The Witch Must Die. New York: Basic Books, 1999.

Cep, Casey N. “The Allure of the Map.” The New Yorker 22 January 2014. Web.

Chandler, Arthur R. The Story of E.H. Shepard: The Man Who Drew Pooh. West Sussex: Jaydem, 2000.

Crossley-Holland, Kevin. The Norse Myths. New York: Pantheon Books, 1980.

Curtius, Ernst Robert. “Dante.” Modern Critical Interpretations: Dante’s Divine Comedy. New York: Chelsea House, 1987.

De Gennaro, Angelo A. The Reader’s Companion to Dante’s Divine Comedy. New York: Philosophical Library, 1986.

Delamar, Gloria T. Mother Goose: From Nursery to Literature. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1987.

Dempsey, Jack and David Dempsey. “Michigan Authors: Holling Clancy Holling, born between Lansing/Jackson, ignited young readers’ imaginations.” MLive Blog. MLive.com, 18 August 2013. Web.

Duriez, Colin. The J.R.R. Tolkien Handbook : A Comprehensive Guide to his Life, Writings, and World of Middle-Earth. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1992.

Fonstad, Karen Wynn. The Atlas of Middle-Earth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1991.

Foster, Robert. Tolkien’s World from A to Z: The Complete Guide to Middle-Earth. New York: Ballantine Books, 1971.

Gannett, Ruth Stiles. My Father’s Dragon. New York: Random House, 1986.

Gilbert, Elliot L. The Good Kipling: Studies in the Short Story. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1972.

Gopnik, Adam. “Broken Kingdom: Fifty Years of “The Phantom Tollbooth.” The New Yorker 17 October 2011. Web.

Green, Roger Lancelyn. Andrew Lang. London: The Bodley Head, 1962.

Greensleet, Ferris. The Quest of the Holy Grail: An Interpretation and a Paraphrase of the Holy Legends. Boston: Curtis & Cameron, 1902.

“H.P. Lovecraft.” Encylopedia of World Biography. Detroit: Gale, 1998. Biography in Context. Web. 30 Dec. 2014.

Hill, Gillian. Cartographical Curiosities. London: The British Library, 1978.

Hopkins, Martha E. Language of the Land: The Library of Congress Book of Literary Maps. Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1999.

Jacobs, Frank. Strange Maps: An Atlas of Cartographic Curiosities. New York: Penguin, 2009.

James, Brian R. and Eric Menge. Menzoberranzan: City of Intrigue. Renton, WA: Wizards of the Coast, 2012.

Juster, Norton. The Annotated Phantom Tollbooth. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1961.

Kirk, E. J. Beyond the Wardrobe: The Official Guide to Narnia. New York: HarperCollins, 2005.

Lang, Andrew. The Rainbow Fairy Book. New York: Books of Wonder, 1993.

Lansing, Richard, ed. The Dante Encylopedia. New York: Garland, 2000.

Lynn, Ruth Nadelman. Fantasy Literature for Children and Young Adults: A Comprehensive Guide. Fifth ed. Westport, Connecticut: Libraries Unlimited, 2005.

Machosky, Brenda. “Trope and Truth in ‘The Pilgrim’s Progress.’” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900. 47.1 (Winter 2007) : 179-198.

Manguel, Alberto and Gianni Guadalupi. The Dictionary of Imaginary Places. Expanded ed. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1987.

Maxwell, Emily. “The Smallest Giant in the World, and the Tallest Midget.” The New Yorker 18 November 1961: 222.

Morgan, Judith and Neil Morgan. Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel: A Biography. New York: Random House, 1995.

O’Neill, Thomas. “Guardians of the Fairy Tale: The Brothers Grimm.” National Geographic 196.6 (December 1999): 103-129.

Peterson, Audrey. Victorian Masters of Mystery: From Wilkie Collins to Conan Doyle. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1984.

Philbrick, Nathaniel. Why Read Moby-Dick? New York: Penguin, 2011.

Post, J. B. An Atlas of Fantasy. Baltimore: The Mirage Press, 1973.

Pratchett, Terry. Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion – So Far. New York: William Morrow, 2014.

Pratchett, Terry and Stephen Briggs. The Discworld Mapp. London: Corgi Books, 1995.

Quilligan, Maureen. The Language of Allegory: Defining the Genre. Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1979.

Rahn, Suzanne. The Wizard of Oz: Shaping an Imaginary World. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1998.

Rogers, Katherine M. L. Frank Baum: Creator of Oz. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2002. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2010.

Schlobin, Roger C., ed. The Aesthetics of Fantasy Literature and Art. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1982.

Shulevitz, Judith. “Don’t Mess with Aslan.” The New York Times 26 August 2001. Web.

Smokler, Kevin. Practical Classics: 50 Reasons to Reread 50 Books You Haven’t Touched Since High School. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2013.

Smyth, Edmund J, ed. Jules Verne: Narratives of Modernity. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2000.

Stableford, Brian. Historical Dictionary of Fantasy Literature. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2005.

Tolkien, J.R.R. Tales from the Perilous Realm. Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2008.

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Shaping of Middle-Earth: The Quenta, the Ambarkanta, and the Annals. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1986.

Walsh, Marian M. “Introducing ‘Pilgrim’s Progress.’” The English Journal. 37.8 (Oct. 1948): 400-403.

Weiher, David. The Two Grail Heroes of Edwin Austen Abbey’s Quest of the Holy Grail. Thesis. University of Massachusetts, Boston, 1999.

Wullschläger, Jackie. Inventing Wonderland: The Lives and Fantasies of Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear, J. M. Barrie, Kenneth Grahame and A. A. Milne. New York: The Free Press, 1995.

Yeoman, Ann. Now or Neverland: Peter Pan and the Myth of Eternal Youth. Toronto: Inner City Books, 1998.

Credits

Lauren Chen

Stephanie Cyr

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center Staff

Lauren Chen, Cataloger

Alison Cody, Development and Program Manager

Stephanie Cyr, Assistant Curator of Maps

Ronald Grim, Curator of Maps

Michelle LeBlanc, Director of Education

Janet Spitz, Executive Director

Evan Thornberry, Reference and

Preservation Librarian

Catherine Wood, Office Manager

Graphic Design and Production

Framing and Matting

Neil Horsky

Andrew Leonard

Digital and Web Services

Tom Blake

Bahadir Kavlakli

Contributors to the Exhibition

Trustees of the Boston Public Library

Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Rare Books and Manuscripts Department

Special Thanks for Contributions to the Collection

Curtis Brown Group Ltd, London

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company

Weta Workshop

Press

Road Maps to Imagination at Boston Public Library

The MetroWest Daily News, March 29, 2015

Two shows look at maps both real and imagined

The Boston Globe, February 27, 2015

Museums & Galleries – Finding Neverland

The Improper Bostonian, February 25 – March 10, 2015

Literary Landscapes

The North End Regional Review, February 10, 2015

BPL Presents ‘Maps from Fiction’ Exhibit

Boston Magazine, February 5, 2015